Written by James Warne

With zero-till the answer is probably never.

The reason behind the question is that once again seed drills have been out in the field before the soil conditions are suitable. Putting seed into the ground and getting it to emerge consistently and evenly is all about seed to soil contact, and drilling depth. Seed to soil contact is about tilth and soil consolidation behind the drill. Drilling depth should be easy to achieve with modern drill technology and level fields.

With cultivated soils, this is in reality easy to manage and achieve providing the soil moisture condition are right for the soil texture and type of machine. The zero-tillers however do not have the benefit of cultivation and have to rely on a heavy dose of patience, and management skill to achieve the right soil conditions, along with the correct choice of drill.

At the moment it’s easy to find situations like the ones highlighted in the pictures below due to poor soil conditions at drilling.

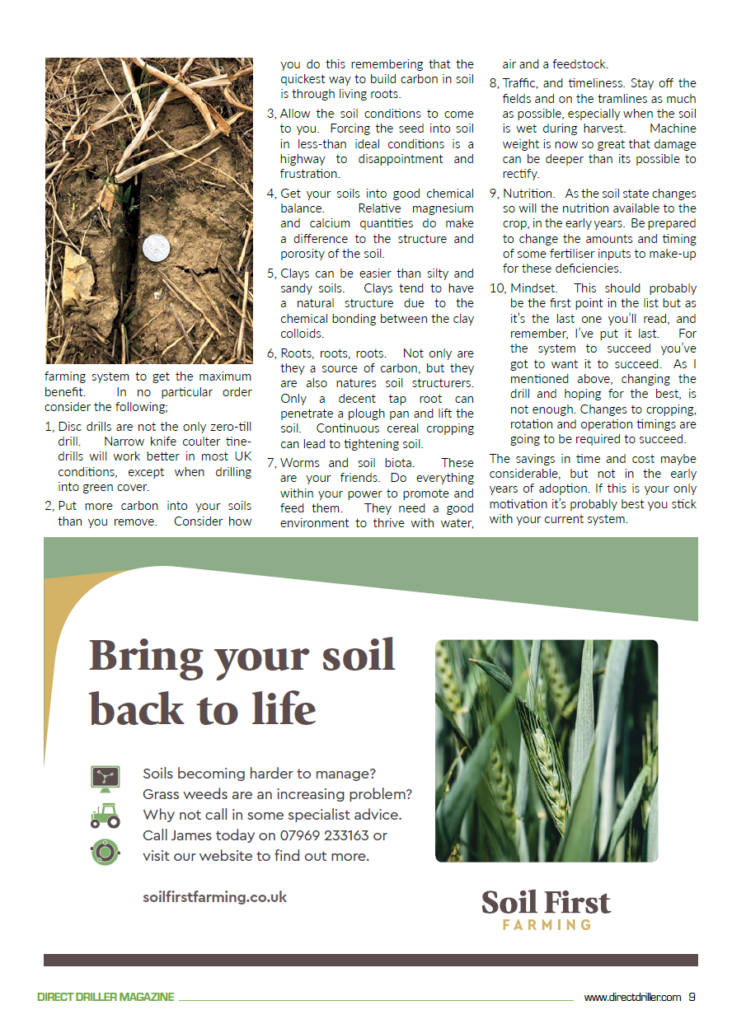

While the drilling above may not look too bad from a distance, closer inspection reveals a lack of slot closure and very little seed to soil contact.

What is tilth and why does it matter?

Good tilth can be described as the physical condition of the soil. In agricultural terminology it generally refers to a soil which is easily to crumble and forms small stable aggregates or crumbs. Tilth can change rapidly depending upon a variety of environmental factors. It’s also important to note that disc-based drills do not create any tilth, whereas a tine-based drill operated correctly has the ability to create enough tilth, in the right conditions, to cover seed.

How do we achieve the right conditions for zero-till spring drilling?

Zero-till has to be viewed as one element in the establishment system. Most long-term arable soils are now so low in organic matter that the natural tilth and structure is very poor. Our soils tend to slake, cap and slump very easily now when left fallow over winter. Add to this the continual rainfall experienced since last autumn pounding fallow ground destined for spring drilling, and it’s very easy to end up with situations like those pictured. Soil with little life, and poor structure, as pictured will not easily produce suitable conditions for zero-till drilling. The pictures below show disc-drilled crops into fallow soil. With little consolidation and zero tilth, the slots are opening up as the surface dries, exposing the roots and stem base and roots to the air causing greater moisture loss from deeper in the soil profile. These plants tend to become stunted and fail to express their full potential.

Given the dry conditions we are now experiencing, and seem to be set in for the next 10 days at the time of writing, the crops pictured are almost certainly destined to be failures.

How do we avoid the failures?

I mentioned earlier that zero-till needs to be considered as part of a system. Simply stopping cultivating and buying a zero-till drill and expecting it to work faultlessly is not enough. Zero-till requires a wholescale adaption of the farming system to get the maximum benefit. In no particular order consider the following;

1, Disc drills are not the only zero-till drill. Narrow knife coulter tine-drills will work better in most UK conditions, except when drilling into green cover.

2, Put more carbon into your soils than you remove. Consider how you do this remembering that the quickest way to build carbon in soil is through living roots.

3, Allow the soil conditions to come to you. Forcing the seed into soil in less-than ideal conditions is a highway to disappointment and frustration.

4, Get your soils into good chemical balance. Relative magnesium and calcium quantities do make a difference to the structure and porosity of the soil.

5, Clays can be easier than silty and sandy soils. Clays tend to have a natural structure due to the chemical bonding between the clay colloids.

6, Roots, roots, roots. Not only are they a source of carbon, but they are also natures soil structurers. Only a decent tap root can penetrate a plough pan and lift the soil. Continuous cereal cropping can lead to tightening soil.

7, Worms and soil biota. These are your friends. Do everything within your power to promote and feed them. They need a good environment to thrive with water, air and a feedstock.

8, Traffic, and timeliness. Stay off the fields and on the tramlines as much as possible, especially when the soil is wet during harvest. Machine weight is now so great that damage can be deeper than its possible to rectify.

9, Nutrition. As the soil state changes so will the nutrition available to the crop, in the early years. Be prepared to change the amounts and timing of some fertiliser inputs to make-up for these deficiencies.

10, Mindset. This should probably be the first point in the list but as it’s the last one you’ll read, and remember, I’ve put it last. For the system to succeed you’ve got to want it to succeed. As I mentioned above, changing the drill and hoping for the best, is not enough. Changes to cropping, rotation and operation timings are going to be required to succeed.

The savings in time and cost maybe considerable, but not in the early years of adoption. If this is your only motivation it’s probably best you stick with your current system.