Mar 2025

On an April day 90 years ago, Hugh Bennett was testifying to the US congress, trying to instil a sense of urgency about the precarious state of American soils. As he spoke, soil blew in from the great plains 1500 miles away, blocking out the sun and giving the day the name by which it would later be known: Black Sunday. As the light failed, he pointed to the window, “This, gentlemen, is what I’m talking about”

In the absence of evidence so stark, it can feel frustratingly hard to galvanize political action. This winter I’ve become more familiar with the corridors of Parliament than I ever could have imagined when playing jazz in the working men’s clubs of 1980s West Yorkshire, or records in Ibizan DJ booths, or farming for 15 years in SW France. After a long time spent working with members of the DEFRA team on an SFI option that would reward farmers for delivering measured nature outcomes whilst growing food (rather than instead of it), the news of the SFI suspension came as an unexpected blow. More immediately, it was a financial nightmare for many farmers, who began to doubt that any future government support could be relied upon.

The message I’ve delivered at various forums over the last few months is always a version of trying to encourage a more holistic view; that the only affordable long term flood protection is supporting farmers to improve infiltration rates in their soils, and paying them to do so isn’t a subsidy but an investment with superb returns. Or that supporting nature rich food production is the only way we are likely to meet legally binding 2030 species recovery targets without offshoring even more of our food supply.

Perhaps the reason why well-applied regen, a solution to so many problems, is being embraced more slowly than it should be, is because it’s a system not a practice. After centuries of scientific advances based on reductionist methodology – a single variable in a controlled environment – our collective ability to think systemically is compromised. System-based research sits outside familiar disciplines. But with the potential of AI to help us understand complexity, soil and ecosystem science should be entering a new golden age.

On 1st January, Ed Brown become head of farming at Wildfarmed. Already his vast experience has been a huge addition for our community of growers. His insights made our late winter open days some of the best received of any Wildfarmed community events.

He and I are working together at my farm, including a first try (for me) at growing rape. With buckwheat and berseem clover companions acting as flea beetle decoys, the crop got off to a good start. Then, late February, the pigeons found it. In a matter of days, they transformed a verdant, leafy canopy into bare earth riddled with stripped and battered stems; a miniature of World War One woodland. Who needs over-winter grazing with pigeons like these?

A week’s worth of astonishingly expensive double action bangers seemed to give the leaves just enough breathing space to get away again. Time will tell what impact the birds have had on yield.

Yet another illustration of why we need nature on farm spreadsheets was illustrated by research which discovered that when swifts are foraging, they seek out the larvae of the cabbage flea beetle.

There has been a 40-50% decline in swifts since 1995, largely linked to declines in insect populations. Meanwhile, Rape continues to be decimated by flea beetle, despite repeated special dispensations to use neonicotinoids. The area sown to Rape has declined 59% since 2012. Yet for those with rent to pay, astronomical machinery costs and no SFI support for the foreseeable future, taking a long-term view on how to get the swifts back is not a realistic option. Collectively, however, we know that we can.

Results from Wildfarmed’s 2024 insect abundance trial with Bristol University across 17 sites are still awaiting peer review, but the headline result was a year-one doubling of insect biomass in Wildfarmed fields compared to neighbouring Conventional controls. One way or another, we must find a way to get this financially rewarded in the same way that we have begun to do for water quality. Farmers can only deliver what they are incentivised to deliver, and this has to include nature-based food production.

A lot of regen discussions are suffering from carbon myopia. This is despite much of recent history being a story of narrow optimisation at the expense of the whole. As an example, when timber was the main driver of economic growth, pioneering 19th century Prussian tree scientists increased production by overseeing the felling of vast tracts of ancient forests, replacing them with managed, fast growing coniferous monocultures. Their yield and carbon numbers were excellent. It was an ecological disaster.

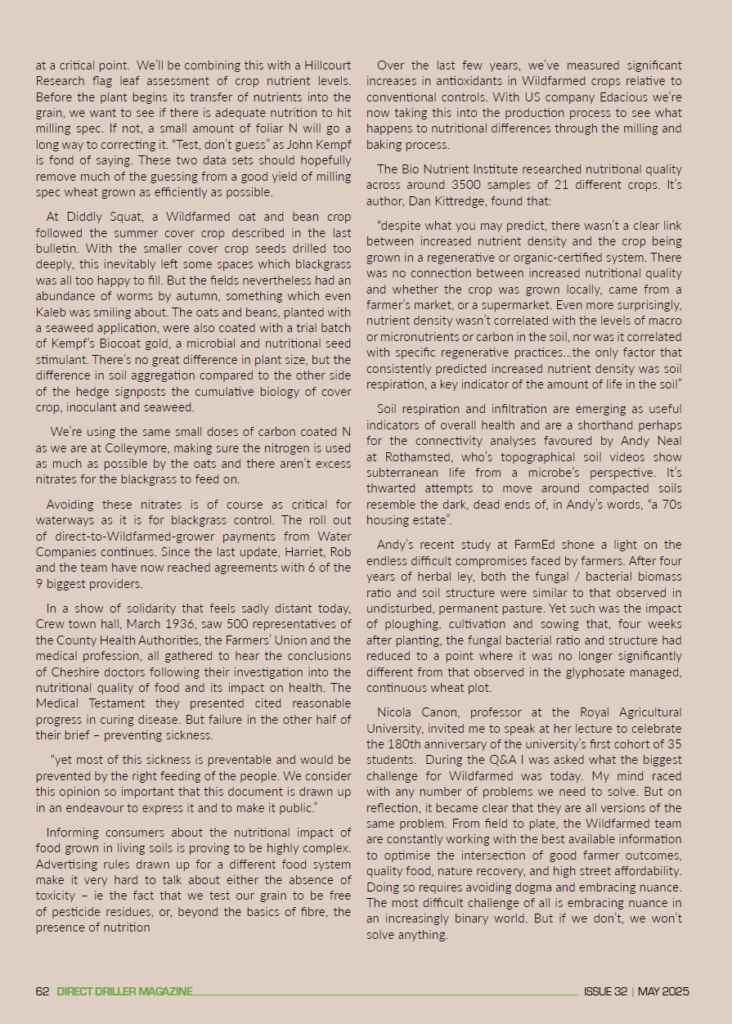

Spring drilling has shone a light on how bad it’s been these last few years. When was the last time when, early April, everything was drilled and there was a moment to watch things grow? On the lower land at Colleymore, where there are still some compaction issues to deal with, it involved a compromise. Whilst the soil surface was dry and it would drill well, a few inches down it was still wet clay. Cultivating to alleviate compaction was not a sensible option. It would wreak havoc on soil structure, create clods that would have to be intensively worked down, and mean losing all the moisture which, in a climate that increasingly oscillates between extremes of wet and dry, we need to retain. So instead, we added a brassica to our wheat and pea combination, in the hope that its tap root would do some of the decompaction work for us. These went in with a dose of fish hydrolysate and seaweed to get microbial activity off to the best possible start.

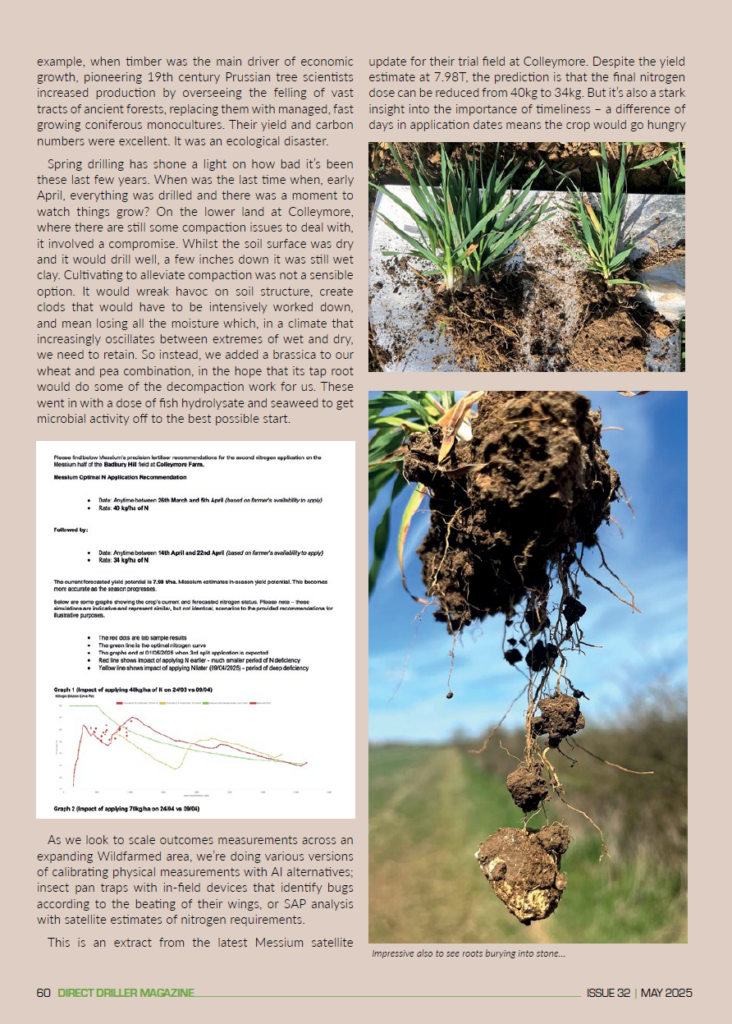

As we look to scale outcomes measurements across an expanding Wildfarmed area, we’re doing various versions of calibrating physical measurements with AI alternatives; insect pan traps with in-field devices that identify bugs according to the beating of their wings, or SAP analysis with satellite estimates of nitrogen requirements.

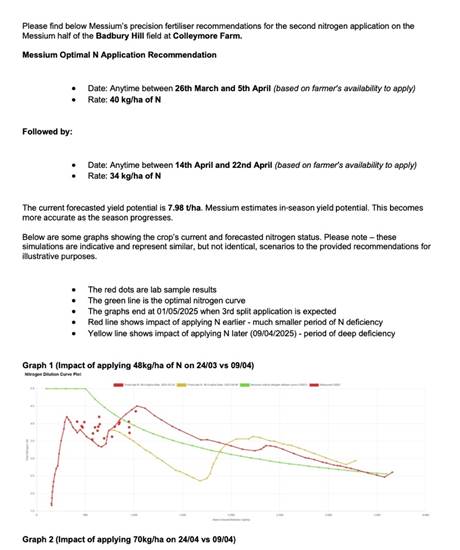

This is an extract from the latest Messium satellite update for their trial field at Colleymore. Despite the yield estimate at 7.98T, the prediction is that the final nitrogen dose can be reduced from 40kg to 34kg. But it’s also a stark insight into the importance of timeliness – a difference of days in application dates means the crop would go hungry at a critical point. We’ll be combining this with a Hillcourt Research flag leaf assessment of crop nutrient levels. Before the plant begins its transfer of nutrients into the grain, we want to see if there is adequate nutrition to hit milling spec. If not, a small amount of foliar N will go a long way to correcting it. “Test, don’t guess” as John Kempf is fond of saying. These two data sets should hopefully remove much of the guessing from a good yield of milling spec wheat grown as efficiently as possible.

At Diddly Squat, a Wildfarmed oat and bean crop followed the summer cover crop described in the last bulletin. With the smaller cover crop seeds drilled too deeply, this inevitably left some spaces which blackgrass was all too happy to fill. But the fields nevertheless had an abundance of worms by autumn, something which even Kaleb was smiling about. The oats and beans, planted with a seaweed application, were also coated with a trial batch of Kempf’s Biocoat gold, a microbial and nutritional seed stimulant. There’s no great difference in plant size, but the difference in soil aggregation compared to the other side of the hedge signposts the cumulative biology of cover crop, inoculant and seaweed.

Impressive also to see roots burying into stone…

We’re using the same small doses of carbon coated N as we are at Colleymore, making sure the nitrogen is used as much as possible by the oats and there aren’t excess nitrates for the blackgrass to feed on.

Avoiding these nitrates is of course as critical for waterways as it is for blackgrass control. The roll out of direct-to-Wildfarmed-grower payments from Water Companies continues. Since the last update, Harriet, Rob and the team have now reached agreements with 6 of the 9 biggest providers.

In a show of solidarity that feels sadly distant today, Crew town hall, March 1936, saw 500 representatives of the County Health Authorities, the Farmers’ Union and the medical profession, all gathered to hear the conclusions of Cheshire doctors following their investigation into the nutritional quality of food and its impact on health. The Medical Testament they presented cited reasonable progress in curing disease. But failure in the other half of their brief – preventing sickness.

“yet most of this sickness is preventable and would be prevented by the right feeding of the people. We consider this opinion so important that this document is drawn up in an endeavour to express it and to make it public.”

Informing consumers about the nutritional impact of food grown in living soils is proving to be highly complex. Advertising rules drawn up for a different food system make it very hard to talk about either the absence of toxicity – ie the fact that we test our grain to be free of pesticide residues, or, beyond the basics of fibre, the presence of nutrition

Over the last few years, we’ve measured significant increases in antioxidants in Wildfarmed crops relative to conventional controls. With US company Edacious we’re now taking this into the production process to see what happens to nutritional differences through the milling and baking process.

The Bio Nutrient Institute researched nutritional quality across around 3500 samples of 21 different crops. It’s author, Dan Kittredge, found that:

“despite what you may predict, there wasn’t a clear link between increased nutrient density and the crop being grown in a regenerative or organic-certified system. There was no connection between increased nutritional quality and whether the crop was grown locally, came from a farmer’s market, or a supermarket. Even more surprisingly, nutrient density wasn’t correlated with the levels of macro or micronutrients or carbon in the soil, nor was it correlated with specific regenerative practices…the only factor that consistently predicted increased nutrient density was soil respiration, a key indicator of the amount of life in the soil”

Soil respiration and infiltration are emerging as useful indicators of overall health and are a shorthand perhaps for the connectivity analyses favoured by Andy Neal at Rothamsted, who’s topographical soil videos show subterranean life from a microbe’s perspective. It’s thwarted attempts to move around compacted soils resemble the dark, dead ends of, in Andy’s words, “a 70s housing estate”.

Andy’s recent study at FarmEd shone a light on the endless difficult compromises faced by farmers. After four years of herbal ley, both the fungal / bacterial biomass ratio and soil structure were similar to that observed in undisturbed, permanent pasture. Yet such was the impact of ploughing, cultivation and sowing that, four weeks after planting, the fungal bacterial ratio and structure had reduced to a point where it was no longer significantly different from that observed in the glyphosate managed, continuous wheat plot.

Nicola Canon, professor at the Royal Agricultural University, invited me to speak at her lecture to celebrate the 180th anniversary of the university’s first cohort of 35 students. During the Q&A I was asked what the biggest challenge for Wildfarmed was today. My mind raced with any number of problems we need to solve. But on reflection, it became clear that they are all versions of the same problem. From field to plate, the Wildfarmed team are constantly working with the best available information to optimise the intersection of good farmer outcomes, quality food, nature recovery, and high street affordability. Doing so requires avoiding dogma and embracing nuance. The most difficult challenge of all is embracing nuance in an increasingly binary world. But if we don’t, we won’t solve anything.