Written by Dr David Cutress: IBERS, Aberystwyth University.

- Land sparing and land sharing are two different perspectives on land management towards improving global biodiversity

- The Welsh Government’s Sustainable Farming Scheme proposal appears to favour a land sharing focus despite most policy, industry and sustainability groups having favoured land sparing in the past

- There are pros and cons to both strategies but more recent research seems to suggest that considering case-by-case combinations of the two may be best for biodiversity

Why working with nature and encouraging its recovery is important?

Agriculture represents the single biggest use of land area worldwide, as such it inherently has a large role to play in human interactions with natural systems. With an ever-growing population of mouths to feed, following our historic patterns of expansion would only lead to even more land being converted for food, which is noted as a driving force behind biodiversity losses.

We have previously discussed the importance of naturally diverse biodiversity for improving the resilience and functionality of our ecosystems as well as highlighting some key areas where biodiversity and agriculture interactions can be beneficial (dung beetles, biological pest control, farmland birds). The decline of biodiversity worldwide is significant with over 65% reductions being noted in the numbers of monitored species populations between 1970 and 2016. Biodiversity levels play important roles in the planet’s ability to adapt to climate changes (droughts, floods, natural disasters) and such declines arguably make this more important an issue than climate change itself (despite the lack of media coverage).

To break it down to a basic message, working with nature rather than against it can save us a lot of energy, time and costs (both financial and environmental), therefore, it should be a focus for more efficient and sustainable land management practices. If we try to implement systems that go against nature without careful consideration we will impact ecosystems both up and downstream in ways that we often will not see for 10s or 100s of years.

For example, initial agricultural innovations of monocultural crops harvested with efficient machinery have led to a huge reduction in the species of food crops we now grow, with 75% of all our food being provided by 12 plant species. This reduction in species diversity whilst productively efficient short term is now being seen to have impacts on disease resilience (one pathogen being able to wipe out entire crops), environmental resilience (current species not adapted to hotter drier summers die or yield poorly), soil health (through lowering diversity of associated microbiomes and diverse root structures benefits on soil properties) and habitat loss impacting biodiversity levels.

We are now moving towards increasingly recognising the benefits of nature/biodiversity, through the economic impacts on public goods provided and climate benefits to name just two things. So, how can we look to manage and reduce further potentially negative interactions with nature?

Two of the major overarching strategies that have been discussed across the world and within the literature are land sharing and land sparing, sometimes looked at more simply as intensification and extensification. Despite the 10-year-long controversies between these two strategies, there is still much debate ongoing in the industry and the scientific community, though land sparing is the dominant choice from governments, policy, industry and sustainability-focused groups. Interestingly, however, it is land sharing that is discussed in the Welsh Government ‘Sustainable Farming Scheme’ proposal.

What are land sharing and land sparing (benefits and problems)?

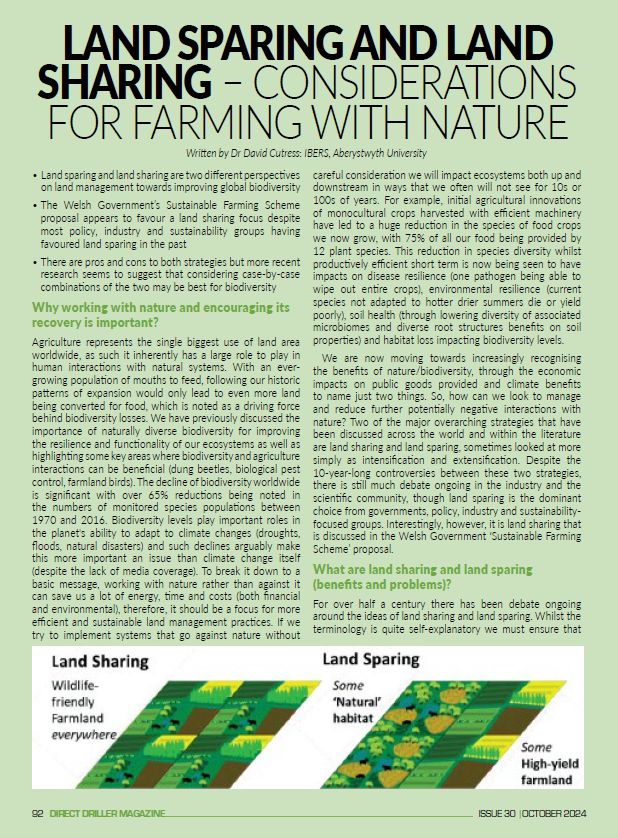

For over half a century there has been debate ongoing around the ideas of land sharing and land sparing. Whilst the terminology is quite self-explanatory we must ensure that the aspects of these two options are understood before we discuss them further. Land sparing involves the consideration that we can merge all of our production needs into fewer highly intensive/efficient smaller areas, ‘sparing’ the remainder of the land (particularly important conservation/protection regions like rain forests and nature reserves) to be utilised for natural biodiversity-friendly ecosystems.

Land sharing on the other hand involves shifting the focus to less intensive more sustainable farming and land management systems across current land space to increase natural mimicry and lead to biodiversity increases across all lands at the same time. Land sparing could have a lot of benefits as it potentially involves less complicated considerations surrounding the recovery and functionality of highly complex natural ecosystems within the land that is ‘spared’ as once established these will require minimal management.

It is often focused on by governments as it can make a country appear far more sustainable depending on the metrics being measured. What land sparing is specifically beneficial for, is conserving species-rich habitats which are often those focused on for protection in sparing strategies, which often contain species with very small global ranges.

However, if land sparing is not considered globally and holistically it can simply lead to the shift of ecosystem/nature impacts elsewhere in the world and, therefore, realistically have no real beneficial impact. For example, if livestock facilities are intensified down to smaller areas and are high-producing systems they will likely require huge feed imports which may simply end up offshoring the issue of monoculture climate-negative crops, such as palm oil and soya.

Similarly, if ecosystems are made the focus then there may be further insufficient land for food production, increasing a nation’s reliance on, and the costs and emissions associated with, food importation. Consolidation of products into smaller intensive spaces may also have negative impacts on farmers’ abilities to spread their investments/risks which should not be overlooked. A concept often linked with land sparing which farmers find controversial is ‘rewilding’. Many believe re-wilding to be a waste of productive land which could otherwise be turning a profit, but it is important to note that subsidies are increasingly available that can make strategies which encourage natural biodiversity increases more beneficial.

Equally many ecosystems are now so degraded or far removed from historic natural states that they cannot easily self-repair without land management assistance, therefore, there could be roles for farmers and land managers to play in the future to be properly reimbursed by sustainability-focused subsidies to assist the ecological restoration of spared lands. Whilst this may benefit innovative, forward-thinking individuals, it of course does act as a barrier to integration for farmers who wish to simply farm as they always have and not re-skill to being ecosystem caretakers.

Land sharing was proposed as a methodology where many individuals do smaller amounts to benefit biodiversity as a whole, and largely many of the techniques associated are already being taken up within the concept of sustainable farming systems which encourage biodiversity.

The extensification that occurs can allow farmers and land managers to spread their production, therefore, spreading their potential yield risks to ensure at least some gains if there are crop or pasture failures. For this concept to work, it requires a change in focus from yields achieved to biodiversity gains, as such it doesn’t answer the consumer needs adequately without a shift from the consumers towards, for example, reduced meat eating and reduced food waste in general.

Whilst both these consumer changes would equally benefit land sparing they are more prominent for land sharing. Furthermore, many early models suggest that land sharing alone would ultimately reduce biodiversity more on the lands that would need to be encroached on (to feed the growing population) than it would improve biodiversity on the lands already being used, leading to a skewed impact.

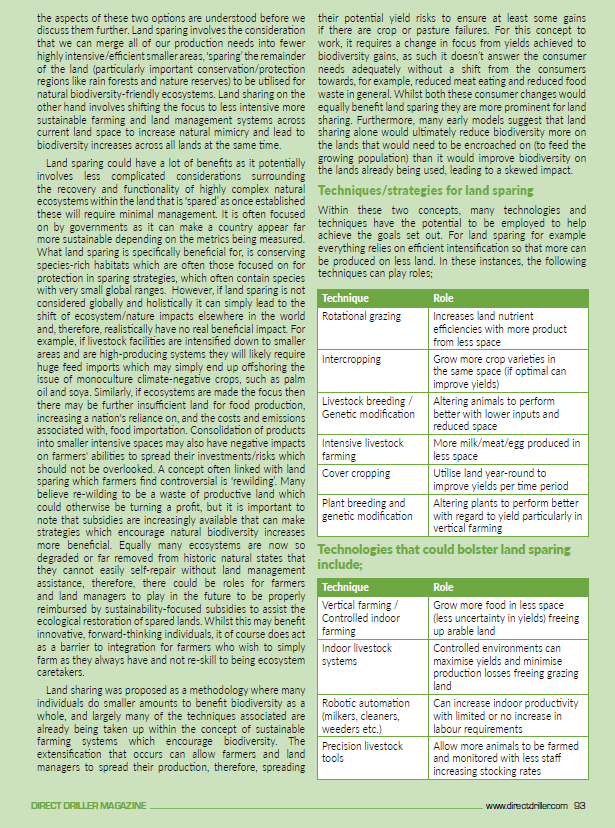

Techniques/strategies for land sparing

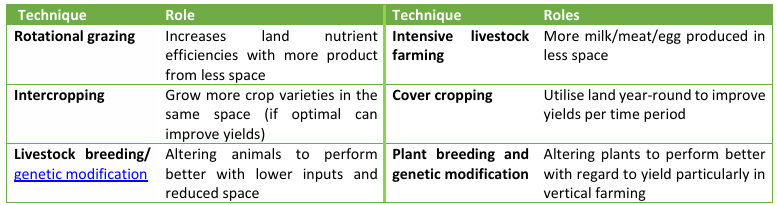

Within these two concepts, many technologies and techniques have the potential to be employed to help achieve the goals set out. For land sparing for example everything relies on efficient intensification so that more can be produced on less land. In these instances, the following techniques can play roles;

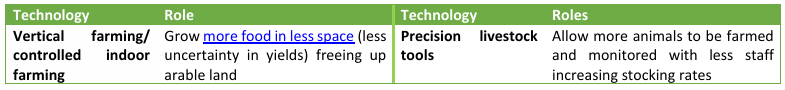

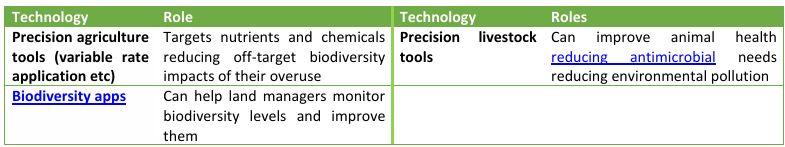

Technologies that could bolster land sparing include;

Whilst these technologies can all benefit more products from less space they may not do so with energy-saving/environmental and animal wellbeing benefits as their key focus.

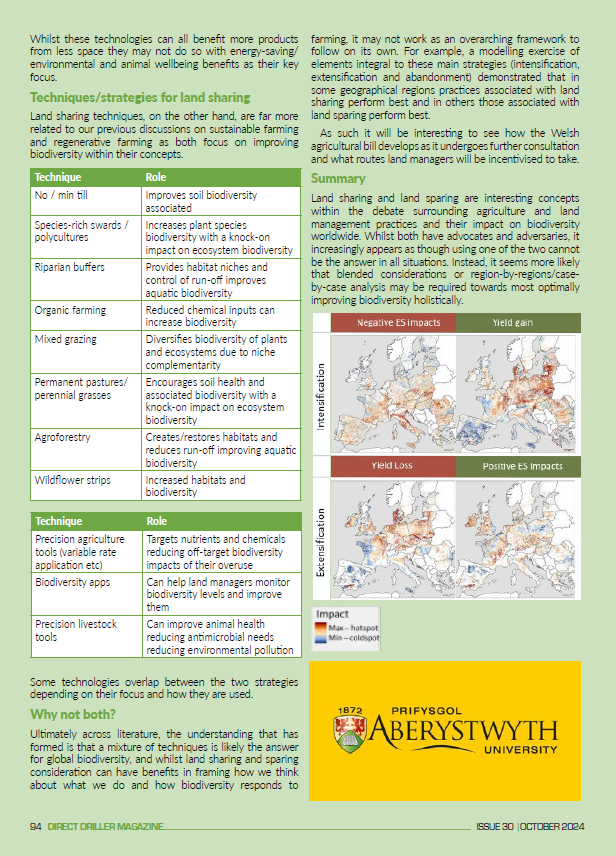

Techniques/strategies for land sharing

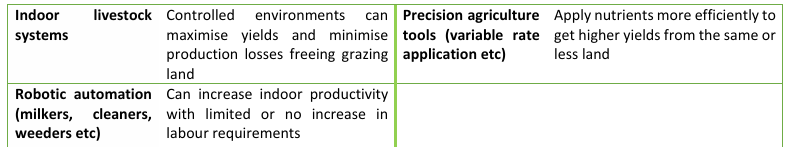

Land sharing techniques, on the other hand, are far more related to our previous discussions on sustainable farming and regenerative farming as both focus on improving biodiversity within their concepts.

Some technologies overlap between the two strategies depending on their focus and how they are used.

Why not both?

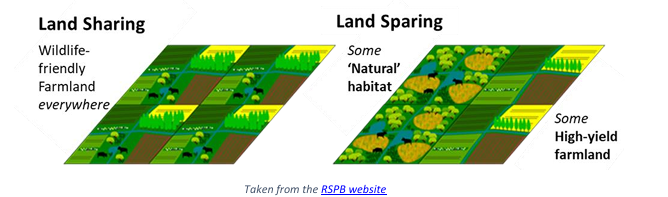

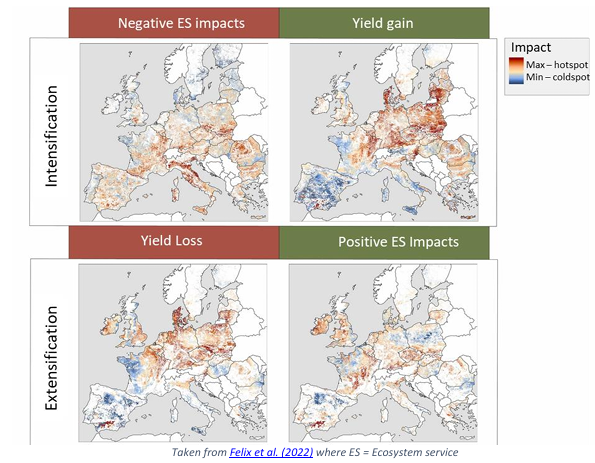

Ultimately across literature, the understanding that has formed is that a mixture of techniques is likely the answer for global biodiversity, and whilst land sharing and sparing consideration can have benefits in framing how we think about what we do and how biodiversity responds to farming, it may not work as an overarching framework to follow on its own. For example, a modelling exercise of elements integral to these main strategies (intensification, extensification and abandonment) demonstrated that in some geographical regions practices associated with land sharing perform best and in others those associated with land sparing perform best.

As such it will be interesting to see how the Welsh agricultural bill develops as it undergoes further consultation and what routes land managers will be incentivised to take.

Summary

Land sharing and land sparing are interesting concepts within the debate surrounding agriculture and land management practices and their impact on biodiversity worldwide. Whilst both have advocates and adversaries, it increasingly appears as though using one of the two cannot be the answer in all situations. Instead, it seems more likely that blended considerations or region-by-regions/case-by-case analysis may be required towards most optimally improving biodiversity holistically.