Written by Nick Adams, Wildlife Consultant, Lower Pertwood Farm

The winds of change are blowing strongly through the Agricultural sector. Leading the charge is the word “wilding” with all its different permutations and options. Lower Pertwood Farm has always had a strong commitment to its wildlife and is fortunate in that it has many acres of land committed to scrub, gorse, woodland and steeply undulating fields which are typical of the Wiltshire chalk downlands in the AONB designated area. For the last 20-years – the last 10 of which has been under the guidance of myself, a freelance naturalist with a sensible approach to the subject – Lower Pertwood Farm has chalked up many successes regarding the creation of habitats which allow certain species to thrive. The true measurement of this is their ability to find a habitat that protects them and provides access to a food source that sustains them.

Wilding is a term that can cause mixed reactions in both the Farming and Conservation communities. From my point of view, I see it used to cover a myriad of conservation work; things that have been carried out for decades with considerable success are sometimes rebranded as cutting-edge. Whereas processes and options I could only dream of are now happening. Farmers I have the pleasure of working with sometimes see it as an attack on their way of living; a push for them to cease food production on their entire holdings and give the land over to species like beaver and pine marten.

At sites like Lower Pertwood, which in recent decades has been c1,000 hectares of mixed organic farming with some mixed conventional farming in the last five years, due to the size and variation in habitats, there will be opportunities to farm for wildlife, humans, carbon and water.

On my first visit to the farm, in late Autumn, it was clear that certain bird species were doing well, namely farmland birds like skylark, linnet, yellowhammer and in particular corn bunting. The first stage of assessment was a year of baseline surveys, to work out where the hotspots were for these species and then to try and work out why that was the case. Perhaps the most important part of my job is finding the current successes, as we might be able to build on those more easily.

impact of changes in farming process is vital.

in February.

May.

Throughout this year, I was having discussions with the agronomist, the landowner and the farm contractor which helped me understand what had happened in the hot spots. Giving positive feedback on what was working and starting to form ideas of what we could consider doing to improve other areas for wildlife. These relationships were vital, two-way communications to show we appreciate each other’s aims and will listen to other’s opinions. We undoubtedly hit the ‘no Nick’ line a few times. This is where I suggest something that is just that bit too much of an impact on the farming process, the response being ‘no Nick, we can’t do that’, the key was the next bit ‘and here’s why’. From there we can further discuss the outcomes we are looking for and often as not, tweak what is happening already or what I was suggesting just a little bit, so it benefits the wildlife without impacting the farming significantly.

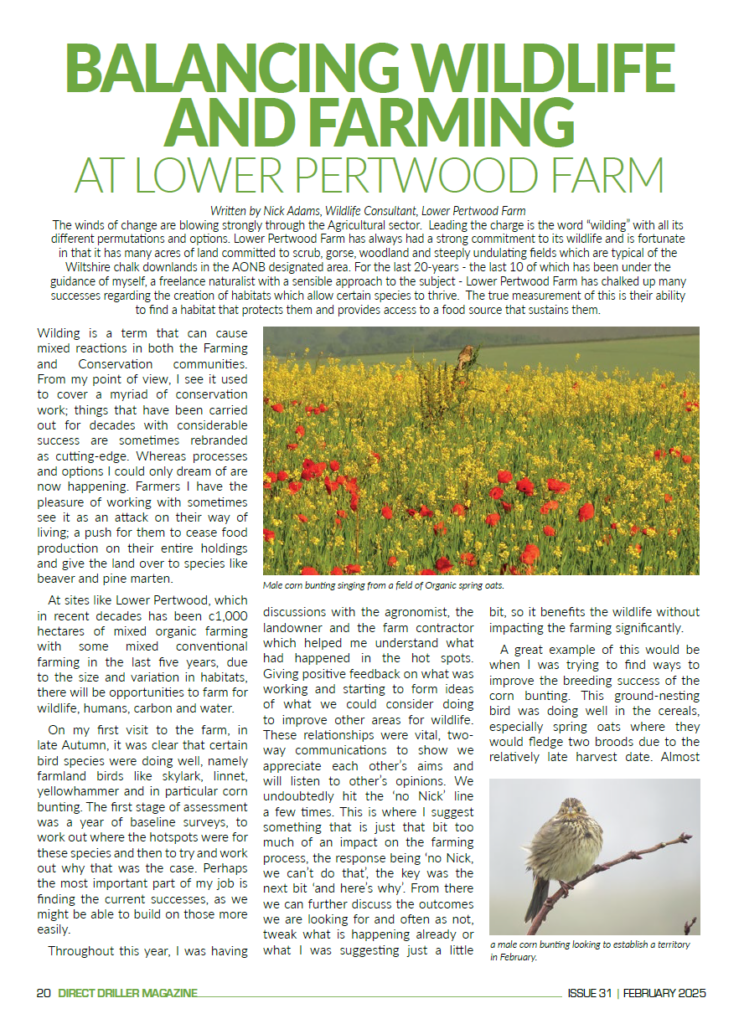

A great example of this would be when I was trying to find ways to improve the breeding success of the corn bunting. This ground-nesting bird was doing well in the cereals, especially spring oats where they would fledge two broods due to the relatively late harvest date. Almost unheard of in a lot of their range as they do not start to nest until the end of May, fledging their first brood in early July.

Being organic, there were significant amounts of herbal leys. Some were cut for forage; others were grazed during the summer and some might just be topped. The baseline surveys had shown me which fields were the priority ones for breeding. This greatly reduced the ‘discussion’ points. For the first Summer after the baseline surveys, we had two fields to consider. Field one had one of the densest populations of corn bunting I had ever seen, 25 territories, a true sacred cow. Field two was important, but not on this scale with six territories. For context, the UK breeding population for corn bunting at the time was around 10,000 territories, a site with 1% of the UK population (100 territories) was considered nationally important, the surveys showed a population of c130 territories. Therefore, these fields were a key part of a nationally important population.

For field one, we had a robust discussion about the available options. It was agreed to take a haylage crop, at the point the corn bunting chicks fledged. I suggested a time of around 10th July for this. As it turned out, this was the date the chicks were on the wing with sufficient strength to avoid the machinery and cutting commenced in the afternoon. The adjacent field had been cut at a more standard time of the year and had regenerated sufficiently to offer immediate cover.

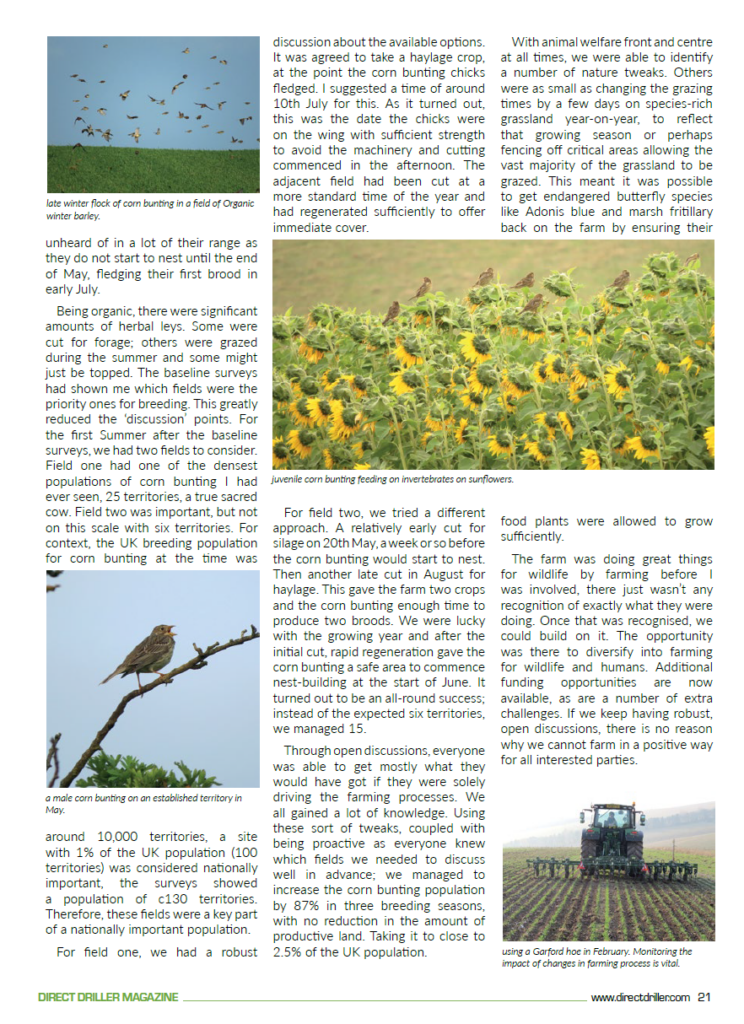

For field two, we tried a different approach. A relatively early cut for silage on 20th May, a week or so before the corn bunting would start to nest. Then another late cut in August for haylage. This gave the farm two crops and the corn bunting enough time to produce two broods. We were lucky with the growing year and after the initial cut, rapid regeneration gave the corn bunting a safe area to commence nest-building at the start of June. It turned out to be an all-round success; instead of the expected six territories, we managed 15.

Through open discussions, everyone was able to get mostly what they would have got if they were solely driving the farming processes. We all gained a lot of knowledge. Using these sort of tweaks, coupled with being proactive as everyone knew which fields we needed to discuss well in advance; we managed to increase the corn bunting population by 87% in three breeding seasons, with no reduction in the amount of productive land. Taking it to close to 2.5% of the UK population.

With animal welfare front and centre at all times, we were able to identify a number of nature tweaks. Others were as small as changing the grazing times by a few days on species-rich grassland year-on-year, to reflect that growing season or perhaps fencing off critical areas allowing the vast majority of the grassland to be grazed. This meant it was possible to get endangered butterfly species like Adonis blue and marsh fritillary back on the farm by ensuring their food plants were allowed to grow sufficiently.

The farm was doing great things for wildlife by farming before I was involved, there just wasn’t any recognition of exactly what they were doing. Once that was recognised, we could build on it. The opportunity was there to diversify into farming for wildlife and humans. Additional funding opportunities are now available, as are a number of extra challenges. If we keep having robust, open discussions, there is no reason why we cannot farm in a positive way for all interested parties.