September 2024

The deluge of the last few days, following the wettest winter since 1836 and the drought of the previous year, make it abundantly clear that we’re now farming in a fundamentally different water cycle. Improving the capacity of our soils to infiltrate and percolate heavy rainfall is going to be critical for a resilient food supply. In his book, The Last Drop, Tim Smedley describes how the Tribunal de de la Vega de Valencia has met every week in the same spot for the past 1,100 years and is recognized as the oldest court on earth. The irrigation system it oversees is one of the many remarkable stories he tells of water optimisation. Iran’s ancient underground ‘qanat’ water network, for example, would stretch 9x around the equator. He describes how in recent decades these localised systems have been replaced by centralised mega projects: vast concrete dams and canals. These slowly emptying water-infrastructure dinosaurs come with some staggering statistics. Lake Mead, the reservoir formed by the Hoover Dam, loses more water through evaporation every year than the total water usage of Las Vegas.

As with water, so in agriculture, when local and nuanced gave way to centralised inputs, varieties and techniques, the initial miracle came with long term consequences that today are urgent and inescapable. One of the challenges we face at Wildfarmed is that the construction of the Hoover Dam or a huge food processing plant, fits much more easily into today’s investment criteria than introducing permeable urban surfaces to help with aquifer recharge or building infrastructure for local food networks. At the heart of this are the “externalities” that aren’t on the spreadsheet; the massive waste of the Hoover Dam whilst the Colorado river no longer reaches the sea, or the myriad statistics describing nature, water and soil decline, with which we’re all too familiar.

In such a world, where a dead tree is worth more than a living tree, a huge amount of Wildfarmed work goes into trying to create a world where farmers are paid not just for the weight of produce, but for its quality and the quality of the ecosystems in which it was grown. It’s a tribute to the tenacity of the team here that from data capture to financial support, we’re making tangible progress; finalising water company payments for our growers, for example, or Trinity Ag Tech analysis that found biodiversity in WF fields to be 100% higher than adjacent conventional production. Last week, hundreds of test tubes of insects went to Bristol University to be analysed for their quantity and diversity of life, data which is all part of building a picture that can bring value onto farmer’s spreadsheets that goes beyond tonnage of grain.

German government money kick-started a process that reduced the price of solar energy 90% in 10 years. Similarly, we need public money to open markets which reward farming that simultaneously delivers on nature and food security. I’ll leave it to those properly qualified to debate where farmed land should give way to rewilding on the one hand, or the pros and cons of “sustainable intensification” on the other. Between these two ends of the spectrum, there are huge tracts of UK farmland where farming that is properly rewarded to combine both food production and nature recovery, is the only way I can see to achieve 2030 legally binding species recovery targets* without either compromising food security or relying on food produced to catastrophic environmental standards from elsewhere around the world. But doing so depends on fair farmer outcomes, and that depends on value being attributed not just to how much food was produced, but how it was produced.

An invitation to speak at an FFCC gathering at the Labour Conference on Monday came long after a DJ set in Ibiza had been agreed for the night before. It made for a surreal 24 hours. The scenes at 5am and 5pm were quite different.

But there was a link. A sign held up in the front row of the Ibizan crowd said “Clarksons! Nature farming ❤️”. Another simply said “Wildfarmed”. A landmark of the last few months has been surpassing 100k Wildfarmed Social Media followers, engaging with the stories of our farmers, bakers, chefs and retailers. In the conference room at the Leonardo Hotel, alongside James Rebanks and Sophie Gregory, I had ten minutes to make my case. The nub of it was that there are lots of good things in today’s SFI, and DEFRA are certainly listening; the changes to AB14 about which I’d been nagging anyone who’d listen for several year did eventually come through, allowing cereal blends, companions and drilling after rape and beans (this is option is now known as AHW10).

But since 1987, when the UK pioneered one of the world’s first Agri-environment schemes, we have sought to increase biodiversity by taking farmland out of production. This shadow of nature and food being a mutually exclusive choice hangs over the SFI, and AHW10 was always an imperfect and temporary solution. A transformational SFI option would be one that gives proper value to nature rich food production, recognising its potential to match or exceed the biodiversity present in today’s well paid, non-productive environmental options. Some of the insect samples sent off to Bristol for analysis showed greater insect abundance in food producing Wildfarmed fields than in £763/Ha beetle banks. Equally transformational would be making certified nature-rich arable a BNG eligible landscape. Food, Nature and Biodiversity Net Gain (FNBNG) would be a global first, bringing BNG outcomes into food-producing landscapes and unlocking private money for farmers who are delivering on both nature recovery and food security in the same place at the same time.

Key to both is measuring outcomes. When the Wildfarmed Standards were drawn up, only 3 years ago, the world of outcomes monitoring was a very different, sparsely populated place. Since then, progress has been rapid and points to a near future where we might replace defining farming practices and define required outcomes instead. An example are polyphenols (anti-oxidants) as indicators of nutritional integrity and therefore functioning soil biology. Back in 1948 William Albrecht correlated the health of US sailors to the health of the soils in their native regions. 80 years later, talk of nutrient density is increasingly common. But a perfectly grown carrot in fully functional soil will have different nutrient levels depending on the geological history of the area. Antioxidants might therefore be a useful indicator of nutritional quality whatever the soil type. We’ve been measuring batches of WF grain for polyphenols over the past few years and found increases of 40% to 100% relative to nearby conventional fields. It will be interesting to see how this data builds up and it’s a shame that such important work is so expensive. Given the epidemic of diet related disease bringing the NHS to its knees, some public money here would be well spent.

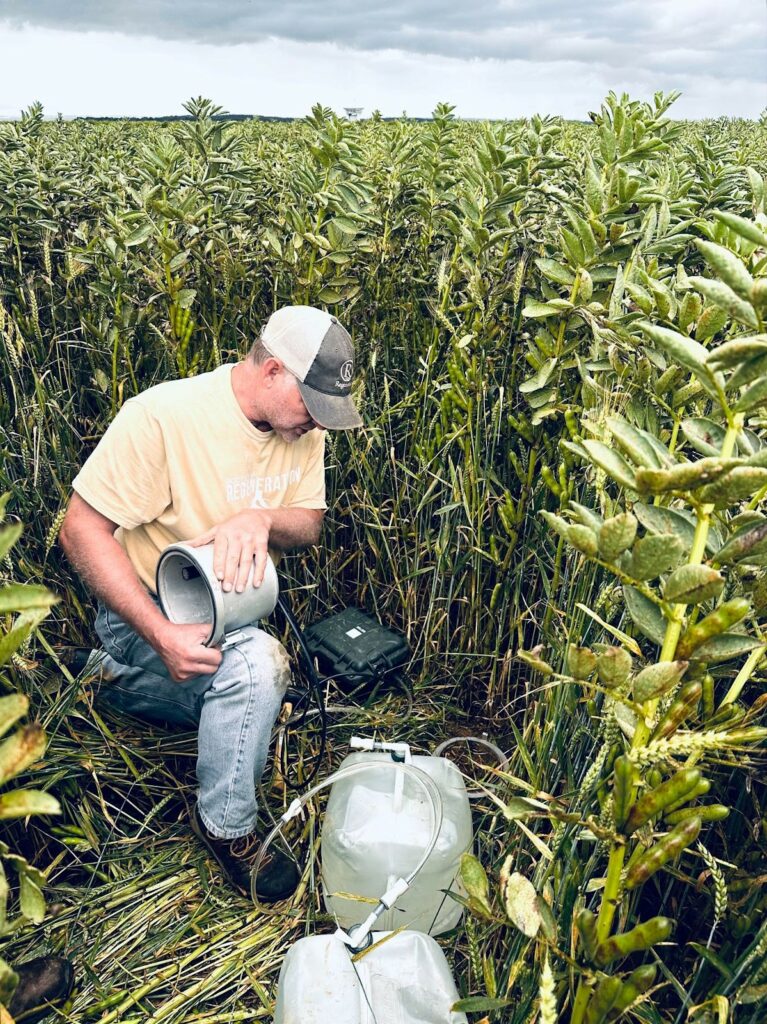

From Acoustic measurements of soils as an indicator of overall system health to satellite analysis of Nitrogen leaching, so many partnerships with Wildfarmed growers are underway to push outcome measuring forward. This includes a pilot with Regenified to gather data across 10 of our farms. On one of them, the Leckford Estate, the Waitrose & Partners HQ with a long history of pioneering farming, I waded into a field of towering wheat and beans to watch Doug Peterson, technical head of the Regenified program, deploy an infiltration measuring machine that costs the same as a family car. This is in stark contrast to the 6” pipe, hammer and ½ litre bottle of water which are my usual tools of the trade.

Infiltration is not only a critical measure of farm resilience in a time of downpours followed by drought but is also itself emerging as a powerful overall indicator of soil health. In a recent highly recommended John Kempf episode with Keith Berns from Green Cover seeds, they discuss the increases in infiltration rates that flow from diverse cover crops, and the increases in water use efficiency of diverse plant communities. Infiltration means porosity, and porosity means carbon and life. In our work with Andy Neal at Rothamsted, porosity, measured using topographical profiling of the soil, is his favoured measure of health.

But amidst all this innovative technology, let’s not forget the creature that is to the soil what the Harpy Eagle is to the forest – the worm. This summer, Jeremy Clarkson put his Wildfarmed fields into a summer long cover crop. Kaleb’s tine drill put the mix in a bit deep, and he’s since fixed himself up with a broadcaster over the drill tines so that next time he can create some tilth whilst tickling the seed into the surface. But despite losing some of the smaller seeded species to these depth issues, the worm count a month ago was amazing. The two samples below show a shovel of soil from the field over the hedge where peas had been harvested, and a shovel from the cover crop field a week after it had been flailed. (Worms under and in the soil samples were put on top to be counted). The next challenge will be getting these fields back into Oats and Beans. There are many areas where the soil goes from Cotswold brash to Cotswold crazy paving.

The big event at the battle of Shrewsbury, as the story unfolded on a recent Rest Is History podcast, was the future Henry V getting an arrow in the eye. The big event for me was hearing how his army advanced through a fields of peas that were full of snakes. I was left wondering where all the snakes have gone and reevaluating the widespread introduction of legumes into English farming which I’d always thought came in the 18th century with Townshend’s Four Course Rotation: Wheat-Turnips-Barley-Clover. I hadn’t realised that legumes had been so widely grown since the Middle Ages, and not just peas but beans and vetches too. It seems to have been the increased Nitrogen fixation of clovers together with replacing fallowing for weed control with hoe-able turnips, that really changed Townshend’s levels of productivity.

But as farmers up and down the country discovered last winter, having soil available nitrogen at the beginning of a cropping cycle is one thing. It being used by the following crop is another and is not straightforward or linear even before we throw in record amounts of rain. It became clear this spring that the amounts of available Nitrogen predicted by soil tests were not becoming a reality, either because of over-winter leaching, or because months of waterlogged conditions meant that the required soil biology wasn’t there. As a result, protein levels were down across the board. For some Wildfarmed growers, already using split N doses and SAP to make a little Nitrogen go a long way, our nutrition-based-on-need approach came up short; the need couldn’t be met. This was one of the key takeaways from the annual process of gathering data and experiences of all our farmers. Combined with the latest learnings from partners such as AEA and Regenified, we’re constantly looking for the best way to facilitate a scalable transition towards farming that meets Wildfarmed customers guarantees: farmer community support, fair farmer outcomes, nature-rich fields, pesticide free grain, avoidance of water pollution, better carbon efficiency.

Avoiding attachment to long held ideas in the face of new evidence is far easier said than done. One of many examples was when, in grass-based Surrey pastures, my first attempt at inter-row-mower pasture cropped UK wheat went into reverse in the spring. Simultaneously I had come across the work of Dr Christine Jones and realised that pasture cropping successes in France hadn’t been because the inter-rows were perennial, but because they were forb based and diverse. Staring at the yellowing, non-symbiotic relationship between annual grasses – wheat – and perennial grasses in those Surrey fields was humbling given I’d thought about pretty much nothing else other than blade tip speed and the million other practical problems that had needed solving throughout the evolution of various mower prototypes over the preceding years. And yet based on the new information, given plant family diversity was the key, and that we were trying to make implementation as easy as possible, surely step one should be the use of poly or bi-crops and cover crops, all doable with existing equipment, rather than try and build a world’s worth of mowers?

Helpful in these moments is to be reminded of the dizzying speed of ecosystem change relative to the trees still alive today that were seedlings when Mammoths walked the earth. Last week, an article detailing further catastrophic butterfly decline and another citing increased pesticide residues in food, were both followed by 5 inches of rain in 24 hours. We’re assailed on all sides by evidence for the urgency of a transition. As such, evidence-based decisions, and avoiding dogma, are, I think, critical if we’re to build field to plate collaborations at the size and scale required to turn things around.

For this year’s annual review around nitrogen, the course correction was more straightforward. The data showed that the amount of N expected from soils that didn’t materialise averaged 40kg. Simply hoping this doesn’t happen again is clearly not an option; without good farmer outcomes, there is nothing to talk about. Instead, we changed the soil-applied nitrogen allowance for our winter sown cereals, from 80kg to 120kg, delivered as always in the split doses of no more than 40kg that are crucial for water quality. Interestingly, studies in Agronomy , Field Crops Research r and Science Direct, all coalesced around 120kg in split doses as the sweet spot between N use efficiency and yield. Given Wildfarmed growers don’t have recourse to pesticides, caution around N use is inevitable given that excess is a sure-fire precursor to disease, or increased weed burdens.

Radical differences in rainfall from one season to the next also affect the management of companion crops; there appeared to be a correlation this year between wetter areas of fields and beans getting ahead of the wheat. It also, of course, has an impact on weeds. This year we’ll be running a series of trials to see how we can best manage both issues in the context of our customer guarantees. Inescapable in these low input systems are all the basics of good husbandry; a rotation that has setup the crop for success followed by good establishment at the higher end of recommended plant populations.

In his book La Vie, John Lewis-Stempel describes a year of small-scale agriculture in a village in the Charente. He measures the output of his vegetable garden and finds the calories produced per sq m to be three times higher than the large-scale farming he had practised in the UK. We encounter this question of scale all the time. On large arable holdings, having enough time to farm differently on a portion of that land can be challenging. And yet pinning a different future on land redistribution feels like rearranging titanic deck chairs. Meeting the world as it is means constantly trying to refine the management of nature rich arable so that there is enough time to focus on the most important thing of all. As Wildfarmed grower Duncan Fairburn put it last week “farming with your eyes”.

This summer saw the arrival of Wildfarmed loaves on the shelves of Waitrose. The first time I saw them in situ, I stood in silence for a while, marvelling at all that had happened to make those loaves become a reality. Building a farming community field by field, the research, agronomy and support team that surrounds that, paying farmers fairer prices whilst trying to remain affordable, bringing everyone across the supply chain together in fields across the country to explain what we’re doing and why, the post-harvest grain separation, storage solutions and milling partners that allow us to keep our grain segregated and traceable from field to plate, persuading plant bakeries operating on wafer thin margins to abandon the Chorleywood process, do an overnight fermentation, leave out the additives, or persuading packaging companies to accept what for them are totally inconsequential print runs. On and on it goes, and then to bring all this together and get a commitment from the different strata of the Waitrose supermarket team to make the first change on the bread isle for 125 years. It’s so incredibly complicated and I take my hat off to the Wildfarmed team for having pulled it off, despite doing so in a market that places no value, yet, on the wider societal benefits of any of this.

Last night, our growers had a post-harvest celebration in the beautiful, wooden dining room at Farm Ed. Farmers are the most resourceful people in the world, and, properly supported, can deliver whatever food and landscapes society asks of them. The last few years have made it clear to me that we can have a future in which farmers are getting fair returns not just for the quality of their food, but for the quality of the ecosystems in which it’s grown. We could have fields that are still full of healthy crops despite the wild changes in rainfall patterns because the soil can infiltrate and percolate water. We could have the brightest young minds coming into food and farming because it’s cool and aspirational. We could have NHS waiting lists coming down because we’re talking about food as medicine. We could have reports in the paper about species diversity going up and up every year. We can do all these things. It’s simply a question of whether, as a society, we choose to do so. As Jane Goodall put it, her diminutive figure on a grey, early morning Glastonbury stage this summer still inspiring new generations to action, “What you do makes a difference – decide what difference you want to make.”

*2019 Environment Act