Which is the lesser of two evils – glyphosate or tillage? That’s what Rothamsted Research’s Prof Andy Neal has been trying to find out

Written By Mike Abram

Glyphosate or tillage – which will do more damage to soil health? It’s a question that has exercised both regenerative farmers and the organic sector from different sides of the same coin.

It also provoked some practical weed control concerns for zero-tillage growers looking to grow crops for Wildfarmed, particularly when a three-year agreement term for a field was being proposed.

While Wildfarmed has rowed back on that proposal, and now effectively allows the use of glyphosate to terminate cover crops, for example, before a Wildfarmed crop is sown – its terms say no pesticides can be used in the growing crop – the debate about which is least damaging led to some research involving Rothamsted Research’s Prof Andy Neal.

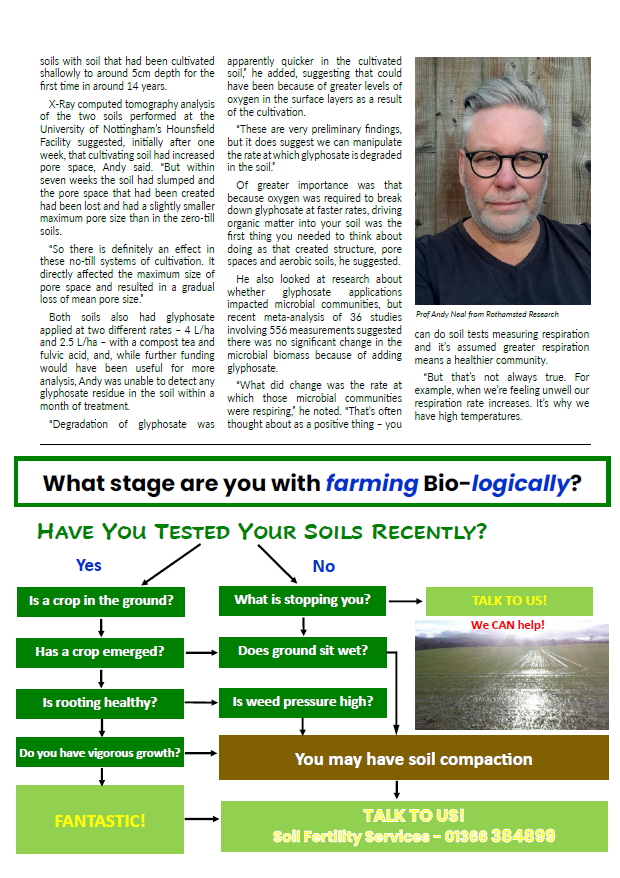

“We were particularly interested in understanding whether it is possible to use glyphosate sensibly and responsibly while still looking after soils,” he told delegates at the Green Farm Collective’s annual regenerative farming conference in May.

That research is still ongoing, with further funding being sought to deliver more insights, but through Andy’s understanding of how soils work, he’s already starting to think about what glyphosate and cultivations are likely to do to soils, as well as look to other research.

Evaluating the risks from glyphosate, he explained glyphosate was broken down microbiologically. “We know this can occur aerobically or anaerobically.

“But in the absence of oxygen it occurs much more slowly. So, when we think about applying glyphosate to soil, ideally that soil would be full of pore spaces and oxygen because under those circumstances we can guarantee it would be broken down as rapidly as possible,” he said.

That suggested there were certain circumstances growers should be considering whether their soil was in a fit state to degrade glyphosate rapidly, and whether growers should address soils in a poor state first, he said.

There were interesting impacts on pore space in the trials Andy conducted in conjunction with Green Farm Collective co-founder Tim Parton last year. These compared long term zero-till soils with soil that had been cultivated shallowly to around 5cm depth for the first time in around 14 years.

X-Ray computed tomography analysis of the two soils performed at the University of Nottingham’s Hounsfield Facility suggested, initially after one week, that cultivating soil had increased pore space, Andy said. “But within seven weeks the soil had slumped and the pore space that had been created had been lost and had a slightly smaller maximum pore size than in the zero-till soils.

“So there is definitely an effect in these no-till systems of cultivation. It directly affected the maximum size of pore space and resulted in a gradual loss of mean pore size.”

Both soils also had glyphosate applied at two different rates – 4 L/ha and 2.5 L/ha – with a compost tea and fulvic acid, and, while further funding would have been useful for more analysis, Andy was unable to detect any glyphosate residue in the soil within a month of treatment.

“Degradation of glyphosate was apparently quicker in the cultivated soil,” he added, suggesting that could have been because of greater levels of oxygen in the surface layers as a result of the cultivation.

“These are very preliminary findings, but it does suggest we can manipulate the rate at which glyphosate is degraded in the soil.”

Of greater importance was that because oxygen was required to break down glyphosate at faster rates, driving organic matter into your soil was the first thing you needed to think about doing as that created structure, pore spaces and aerobic soils, he suggested.

He also looked at research about whether glyphosate applications impacted microbial communities, but recent meta-analysis of 36 studies involving 556 measurements suggested there was no significant change in the microbial biomass because of adding glyphosate.

“What did change was the rate at which those microbial communities were respiring,” he noted. “That’s often thought about as a positive thing – you can do soil tests measuring respiration and it’s assumed greater respiration means a healthier community.

“But that’s not always true. For example, when we’re feeling unwell our respiration rate increases. It’s why we have high temperatures.

“So it would be easy to assume this is a positive influence of glyphosate, but what I think we are seeing is a measure of the stress imposed upon communities as a result of adding glyphosate. It doesn’t mean it is a lethal effect, but means the communities are working harder to break down that glyphosate or to overcome some other effect.”

A second set of studies compared soils where glyphosate had been applied regularly for a long period against organic farms in Maryland, Mississippi and Washington states in the US, with the aim of identifying any changes in microbial community as a result of applying glyphosate.

But what the studies found was that other factors, such as annual variation or how the soil was managed, had a much greater influence on the microbial communities in the different soils than the application of glyphosate.

What those experiments didn’t consider was what those microbial communities were doing, he pointed out. “That’s what we’ve been trying to understand with the Wildfarmed trials on Tim’s farm. We know microbial species change happens, but what’s important is understanding the way microbial function changes as a consequence. That’s what we’re looking to achieve in the next few years,” he said.

So what about the impact of cultivations on soil health? Evidence from Rothamsted’s North Wyke site in Devon suggested that just one year of ploughing reduced organic matter from 6% to 3% when converting fields that had been in long term pasture into an arable system.

“From the trials it suggests it takes roughly seven or eight years to recoup the carbon that was lost under a pasture, as long as no further tillage takes place,” he added.

A second series of trials he highlighted were at FarmEd in the Cotswolds, where the farm incorporates grazed herbal leys into a cereal rotation. Andy has been investigating the impact of multi-species herbal leys on soil structure and the consequences of moving from herbal leys into arable in the rotation.

“We looked at several different treatments on the farm, including a permanent pasture. The four-year herbal ley had the largest amount of pores of any treatment – it had developed a nice structure, which would drain well and hold an awful lot of water.

“But we were shocked that after ploughing shallowly to 10cm, plus two power harrow passes, rolling and drilling reduced the amount of pore space significantly. We would predict this soil will now drain poorly because it will be difficult for water penetrate, and for it to hold onto what water does penetrate because of the lack of pore space.”

Connected pore spacing was crucial for optimal soil function, he explained. “And there is a clear connection between the amount of organic matter that goes into your soil and pore spaces.”

That connection was much stronger in soils with significant clay and / or silt content, and less so in sandy soils, but in those soils with the right texture higher organic matter equalled high porosity leading to a high flux of nutrients and oxygen through the system.

“That will give you a high nutrient use efficiency. Anaerobic space [caused by poor soil structure and lack of connected pores] causes the selection of microbes that use nitrates rather than oxygen to respire, resulting in the production of nitrous oxide, low nutrient use efficiency and high greenhouse gas emissions.”

The implication of making the connection between organic matter, connectivity between pores and soil structure was in how growers might manage how they use organic matter on farm, he suggested.

“If you want to make the biggest impact with small amounts of organic matter you might invest them in clay soils you know to be low in organic matter because that’s where you’re going to see the maximum benefit in improving water holding capacity and improving lots of other metabolic issues associated with anaerobic respiration with microbes,” he concluded.