Pasture for Life, which champions the restorative power of grazing animals, continues to go from strength to strength with ambitious targets of hitting 5,000 members farming one million hectares by 2029.

Last year saw 208 events delivered and 93 farmers trained as grazing mentors helping 166 mentees. There was activity across England, Scotland and Wales, including research collaboration and partnerships, as well as successful supply chain initiatives.

Former director Sara Gregson talks to two Pasture for Life certified producers and reviews a couple of recent research projects…

Pasture for Life farmers

Sonja and Perin Dineley

Dorset

Sonja and Perin Dineley regard themselves as biological farmers, creating healthy living networks in the soil and above ground, whilst producing good food for people to eat.

They run 3,000 New Zealand Romney ewes across 750 hectares on three farms close to Shaftesbury. There is a wide range of soils including chalk, greensand and clay and the farms are at different stages of regeneration.

“Agriculture is not easy at the moment, with the reduction in payments and loss of faith from consumers,” says Perin. “But if we can demonstrate that production agriculture can be integrated with caring for nature, there is plenty of scope for us to succeed and be at the forefront of the future direction for farming.”

The ewes are run in three flocks and lambing starts no later than 10 April to make use of the high quality spring grass.

The lambs are weaned at ten to 11 weeks of age and divided into replacements and breeding stock or killing lambs. They are grouped according to weight and put into the most appropriate fields, including herbal leys.

“We have been rotational grazing lambs for several years, achieving growth rates of 400g/day or more,” Perin explains. “They are moved every three to four days on multi-species swards containing a lot of clover, plantain and chicory. Depending on feed availability, a combination of fat lambs are sold through ABP and some store lambs are sold privately.”

No meat is currently sold from the farm, but the Dineleys have recently become Pasture for Life certified in anticipation of doing so in future.

“We have been raising animals on just forage for 30 years or more,” says Sonja. “We need to find a way of getting this nature value through to consumers. Pasture for Life has a lot of direct selling members, and I am sure we can learn a lot from them.”

A small herd of Belted Galloway cross Shorthorn suckler cows has been introduced and their grazing has made a huge difference to biodiversity, with fabulous shows of wildflowers each summer, including fields with hundreds of Bee Orchids.

“We see our work as restoring damaged ground, which is better than merely sustaining it – who wants to sustain really depleted soils?’ asks Sonja. “Forage diversity with different root formations and root depth is critical to rebuilding soil health and that is what we are aiming for.”

James Newhouse

North Yorkshire

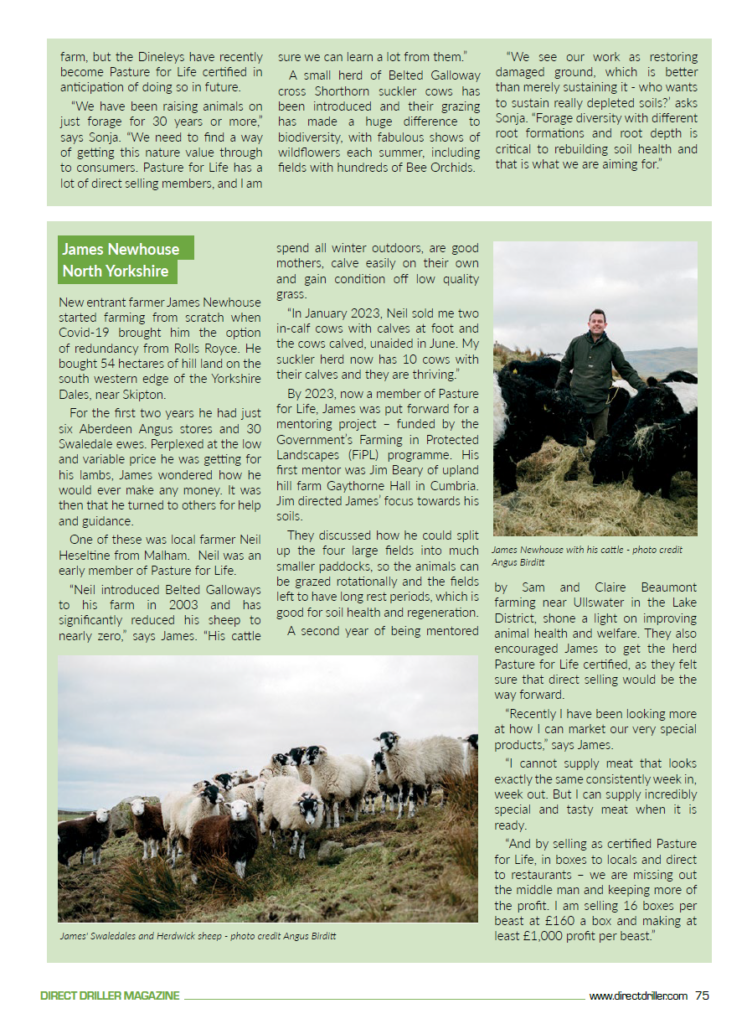

New entrant farmer James Newhouse started farming from scratch when Covid-19 brought him the option of redundancy from Rolls Royce. He bought 54 hectares of hill land on the south western edge of the Yorkshire Dales, near Skipton.

For the first two years he had just six Aberdeen Angus stores and 30 Swaledale ewes. Perplexed at the low and variable price he was getting for his lambs, James wondered how he would ever make any money. It was then that he turned to others for help and guidance.

One of these was local farmer Neil Heseltine from Malham. Neil was an early member of Pasture for Life.

“Neil introduced Belted Galloways to his farm in 2003 and has significantly reduced his sheep to nearly zero,” says James. “His cattle spend all winter outdoors, are good mothers, calve easily on their own and gain condition off low quality grass.

“In January 2023, Neil sold me two in-calf cows with calves at foot and the cows calved, unaided in June. My suckler herd now has 10 cows with their calves and they are thriving.”

By 2023, now a member of Pasture for Life, James was put forward for a mentoring project – funded by the Government’s Farming in Protected Landscapes (FiPL) programme. His first mentor was Jim Beary of upland hill farm Gaythorne Hall in Cumbria. Jim directed James’ focus towards his soils.

They discussed how he could split up the four large fields into much smaller paddocks, so the animals can be grazed rotationally and the fields left to have long rest periods, which is good for soil health and regeneration.

A second year of being mentored by Sam and Claire Beaumont farming near Ullswater in the Lake District, shone a light on improving animal health and welfare. They also encouraged James to get the herd Pasture for Life certified, as they felt sure that direct selling would be the way forward.

“Recently I have been looking more at how I can market our very special products,” says James.

“I cannot supply meat that looks exactly the same consistently week in, week out. But I can supply incredibly special and tasty meat when it is ready.

“And by selling as certified Pasture for Life, in boxes to locals and direct to restaurants – we are missing out the middle man and keeping more of the profit. I am selling 16 boxes per beast at £160 a box and making at least £1,000 profit per beast.”

Research update

Getting farmers more involved with future research

Supported by funding from the UKRI-BBSRC, Rothamsted Research (RR) and Pasture for Life have joined forces to reflect on the current state and potential of pasture-based livestock research.

They believe that moving the science and the public debate forward requires an agricultural research environment which prioritises farmer-scientist collaborative research at the farm-level.

Between May and October 2024, a series of round tables involving a scientific advisory group from Rothamsted Research and Pasture for Life’s research group, followed by an open invite scientist-farmer workshop event, identified shared priorities to encourage more research funding that supports collaborative farmer-scientist research.

The shared vision was for Responsive, Dynamic and Impactful collaborative research.

Recommended changes

Relationship-based research funding

Most current funding models work on an episodic, project-based basis, which limits the opportunity for building long-term trust between scientists and farmers. Introducing a relationship-based funding strand would allow ongoing, mutually beneficial collaborations, fostering stronger partnerships and more effective, timely research.

Equal status as research partners

The current UK funding model does not facilitate the rewarding of farmers as equal partners in the research process. Funding models need to recognise farmers as full partners in research, allowing them to be listed as co-researchers and compensated fairly for their expert contributions.

Deploy a co-design approach

To ensure relevance and effective application of research, collaboration needs to move from its current focus on data collection to a co-design approach, where collaboration applies to the whole research process, starting with identification of the research problem and design of the study.

Read more here: https://bit.ly/43xdfQd

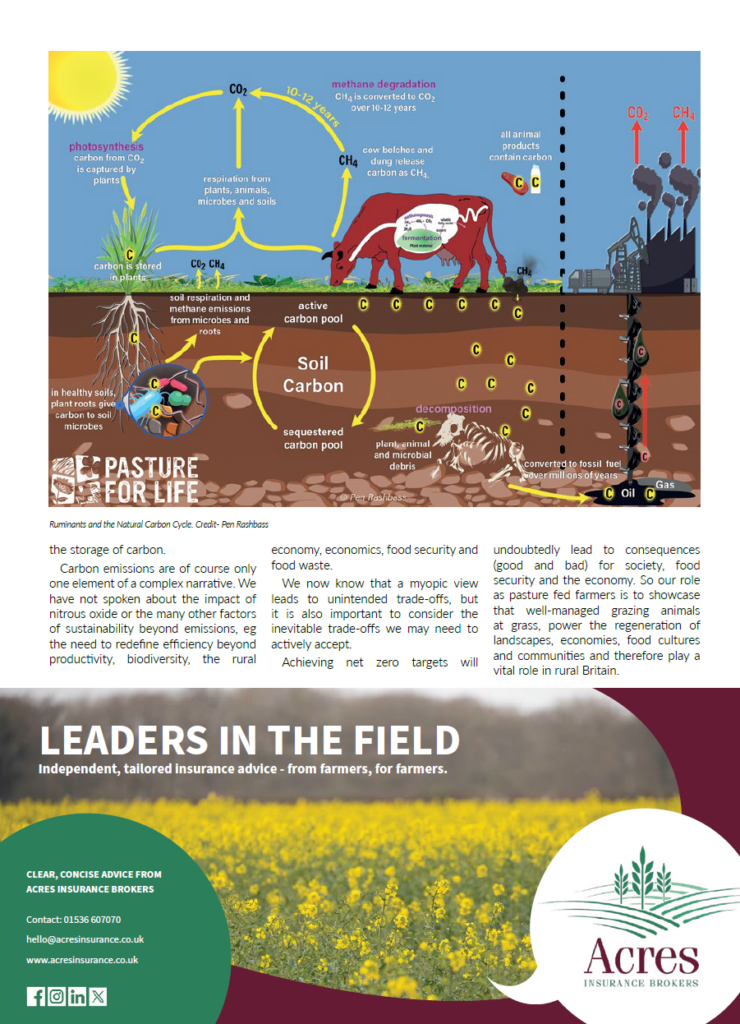

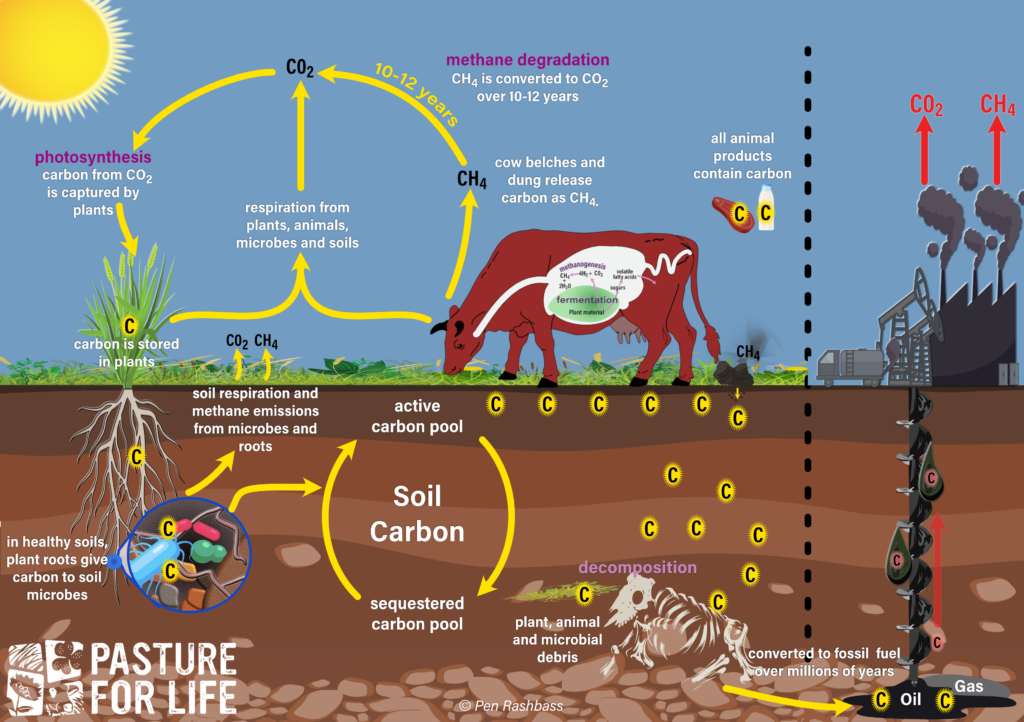

Carbon – a complicated story

Nikki Yoxall has held the roles of Research Group Coordinator and Head of Research at Pasture for Life, but in 2024 became Technical Director, overseeing Knowledge Generation (research and evidence building) and Knowledge Exchange activity.

Here she outlines the organisation’s thoughts on carbon in Pasture for Life Farming Systems

We know that the interactions between soils, vegetation and grazing animals are currently not captured within Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs). However, soil has now been recognised by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), as one of the potentially biggest sinks for atmospheric carbon dioxide. Therefore, with the correct carrying capacity and grazing management, pasture-based livestock systems not only lead to biodiversity rich grasslands and higher productivity, but are also able to store carbon, through their root systems, leading to net zero emissions from the farm, or potentially even acting as sinks.

In addition Pasture for Life farms:

- Use appropriate livestock carrying capacities, where the farmland is able to provide forage self-sufficiency, avoiding the need to buy in feed

- Are naturally more resilient, with lower inputs of fuel, bought-in forage and fertiliser, with the associated reductions in associated emissions

- Provide permanent grasslands and biodiverse habitats to maximise carbon sequestration

- Often have multi-species swards (MSS) and browsing available to livestock that we know contains species that can actively reduce methane emissions eg sainfoin, willow, plantain and bird’s foot trefoil.

What we sadly do not have is enough research focused on ruminants naturally grazing, their direct methane emissions, the ability for grasslands to sequester or the interactions they may play in the short carbon cycle.

Whilst many Pasture for Life farms will feel confident that they are working towards a resilient, farming system that actively supports the health of the water cycle, mineral cycle and carbon cycle, we are all of course part of a much wider global society where expectations are placed on land managers to deliver multiple outcomes, as well as food, for the benefit of society – one of which is the storage of carbon.

Carbon emissions are of course only one element of a complex narrative. We have not spoken about the impact of nitrous oxide or the many other factors of sustainability beyond emissions, eg the need to redefine efficiency beyond productivity, biodiversity, the rural economy, economics, food security and food waste.

We now know that a myopic view leads to unintended trade-offs, but it is also important to consider the inevitable trade-offs we may need to actively accept.

Achieving net zero targets will undoubtedly lead to consequences (good and bad) for society, food security and the economy. So our role as pasture fed farmers is to showcase that well-managed grazing animals at grass, power the regeneration of landscapes, economies, food cultures and communities and therefore play a vital role in rural Britain.