A move towards biological farming is setting one mixed farm up for a better future. Sara Gregson reports

Flood water in the lowest lying fields of Brook Farm, Repton in the East Midlands can hang around for months at a time and is a challenge for crops and animals alike.

Father Andrew Sread with his wife Tina and his sons Martin, in charge of the arable side of the business and James who manages the dairy, are fourth and fifth generation farmers, moving to Repton 18 years ago. The farms cover 571ha (1400 acres) with 122ha (300 acres) owned. The average annual rainfall is more than 900mm (35.4 inches).

On the banks of the River Trent, flood water can come up to the top of five barred gates and ducks can be seen swimming down the tramlines. In one flash flood in May, when Martin went to rescue a new-born calf that was stranded, he was astounded to see voles and mice swimming towards him trying to find dry land.

“Flooding is inevitable here and some low-lying hollows maybe underwater for five months,” he says. “They don’t dredge the river anymore and housing developments and the building of the A50 mean rainfall comes rushing down to our fields. And the water is dirty and oily, not great for growing crops or grazing animals.”

Change of direction

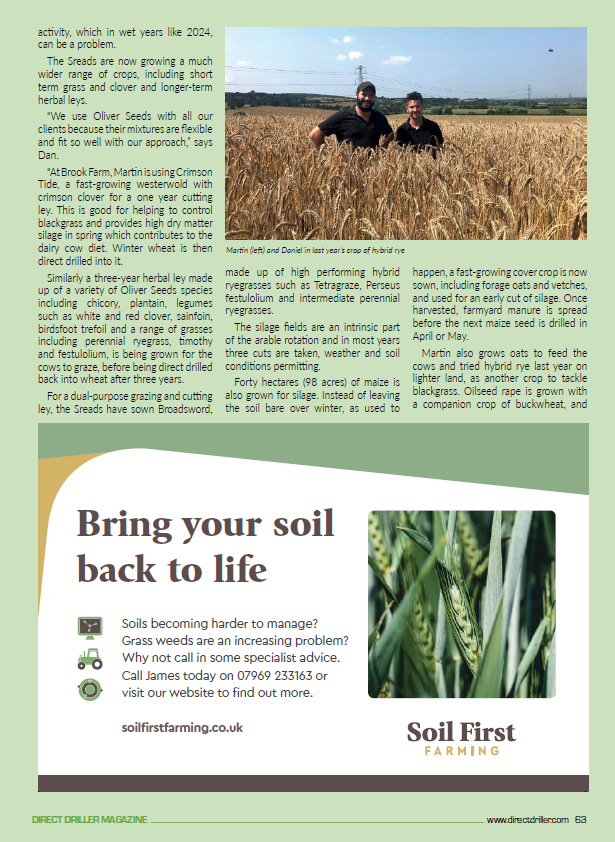

Four years ago, the family was becoming frustrated with ever increasing input bills and declining outputs, in both the arable crops and the dairy herd. They changed their agronomist to Daniel Lievesley from DJL Agriculture based in Derby.

Having worked for an agrochemical distributor, Daniel felt that growing crops relying on chemical and synthetic fertilisers was not the way he wanted to work. He now spends his time transitioning growers towards a biological approach, as he believes this benefits everyone, economically and environmentally.

“We are impressed with Dan’s approach,” says Martin. “He has a completely different mindset to our old agronomist – who only ever wanted to use a different chemical. Dan has taken us back to basics and it is working. Soil organic matter has risen from 2.2% to 3.4% in just four years.

“Three years ago we walked 55 acres looking for earth worms in the soil. There should have been three worms per spadeful, but there were none. Now we can do the same walk and there are many more than three worms and spirals of soil where the worms are pulling it down. We have stopped using insecticides and there are a lot more beetles and other insects too.”

Dan’s approach is also having an effect on the bank balance, with half the fertiliser, half the fungicides and no plant growth regulators used on the cereal crops last year. This has reduced input costs by at least £75/ha.

The Sreads have changed the cereal varieties they grow to ones which may not be so high yielding but have greater resistance to diseases such as septoria and yellow rust. They now do one fungicide spray at T 1.5, rather than three. For example, Extase has yielded 11t/ha but the inputs have more than halved, so the margins are better.

Tackling blackgrass

One of the main problems on the arable side of the business is blackgrass. Dan has advocated different cultivation methods and following a wider rotation.

“In the past we used to plough and use a combi-drill to sow the seeds. When we power harrowed, the soil was a purple/brown colour and it looked dead. Now, after minimal cultivations, it looks crumblier and the structure is definitely opening up and improving.

“We take as much care as possible. We use a low disturbance subsoiler if compaction is a problem, all the tractors have flotation tyres and the combine is on tracks. When it is wet, we never sink into the ground or make deep ruts like we used to.”

Two years ago the Sreads invested in an Amazone Cayena 6001 trailed seed drill, which has saved 60% in fuel usage when establishing crops. They also use a John Deere scruffler and Mzuri straw rake to chit blackgrass weed seeds 2cm below the drill. This also cuts slug activity, which in wet years like 2024, can be a problem.

The Sreads are now growing a much wider range of crops, including short term grass and clover and longer-term herbal leys.

“We use Oliver Seeds with all our clients because their mixtures are flexible and fit so well with our approach,” says Dan.

“At Brook Farm, Martin is using Crimson Tide, a fast-growing westerwold with crimson clover for a one year cutting ley. This is good for helping to control blackgrass and provides high dry matter silage in spring which contributes to the dairy cow diet. Winter wheat is then direct drilled into it.

Similarly a three-year herbal ley made up of a variety of Oliver Seeds species including chicory, plantain, legumes such as white and red clover, sainfoin, birdsfoot trefoil and a range of grasses including perennial ryegrass, timothy and festulolium, is being grown for the cows to graze, before being direct drilled back into wheat after three years.

For a dual-purpose grazing and cutting ley, the Sreads have sown Broadsword, made up of high performing hybrid ryegrasses such as Tetragraze, Perseus festulolium and intermediate perennial ryegrasses.

The silage fields are an intrinsic part of the arable rotation and in most years three cuts are taken, weather and soil conditions permitting.

Forty hectares (98 acres) of maize is also grown for silage. Instead of leaving the soil bare over winter, as used to happen, a fast-growing cover crop is now sown, including forage oats and vetches, and used for an early cut of silage. Once harvested, farmyard manure is spread before the next maize seed is drilled in April or May.

Martin also grows oats to feed the cows and tried hybrid rye last year on lighter land, as another crop to tackle blackgrass. Oilseed rape is grown with a companion crop of buckwheat, and beans and oats are being grown as a bicrop for the first time this year.

Crop nutrition

Dan carries out sap tests, which measure the nutrient concentrations and has them analysed by independent laboratories. This, together with soil sampling, using automated kit on a utility task vehicle (UTV) which is new to Dan’s business this year, gives detailed information on the nutrient composition of the soils.

“Some of the soils at Brook Farm have a high pH and are also high in magnesium,” says Dan. “I have advised Martin to spread humates and fulvates that feed the soil and naturally increase uptake of nutrients in plants. Also to spread boron at crop establishment in fields with excessive levels of calcium, as this prevents boron deficiency later. Applications of sulphur are also needed to help with nitrogen uptake.

“Foliar feeds containing magnesium, calcium and potassium are also made up and sprayed onto the crops. Adding nutrients that are shown to be needed, do many jobs – including adding strength to the cereal straw so no PGRs are required, and also help overcome disease and pest pressure.

“High calcium fertilisers are applied to the cow pastures which has reduced the cost of bought-in nitrogen by 20%.”

Dairy cows

The dairy herd is also going through transition, as James is moving away from pure Holsteins to a smaller, more resilient cow.

“We are looking to have a stronger, healthier animal that has good feet. She may have slightly less output, but she will also have less problems.” says James. “We introduced a Lineback bull, a rare American breed, three years ago and are now back-crossing to Shorthorn, Montbeliarde and Ayrshire.”

The 200-cow closed herd calves all year round and has an annual average milk yield of 7,500 litres. All the calves are reared on pasteurised whole milk and creep feed. The males are sold at Melton Mowbray and Leek markets and all the females are kept as replacements.

The cows are loose housed in winter on straw from the arable side of the business. This is put back to the arable fields as farmyard manure.

One hundred tonnes of home-grown winter cereals are milled, added to the various winter forages and fed as a total mixed ration (TMR). Bought-in cake is also fed in the parlour.

The cows graze 61ha (150 acres) of permanent pasture which has never been ploughed. Extended flooding in some of these fields left bare patches which were overseeded last autumn.

The milk is sold to Arla on a high animal welfare contract. The Sreads have also recently started to sell milk and milk shakes to the public through a vending machine in the farmyard under their Mercia brand.

“We are continually adapting our management of the whole farm – treating the soils, the arable crops, the grazing ground and the cows as a whole,” says Martin. “We are still in the transition phase, but we know the direction we want to be travelling in and Dan is helping us achieve this. Despite the challenges we face, we are now definitely in a much better place.”

DJL Agriculture promotes biological farming solutions to ensure farming success and profitability by putting life back into farmers’ soils. Daniel Lievesley concentrates on the cropping side of clients’ businesses, while his father David works with dairy, beef and sheep producers delivering holistic nutrition consultancy.

David recently wrote a poem about where he sees farming has gone wrong in the past, and where a regenerative approach and a focus on soil health, can take farmers in the future.

Soil

The soil as the answer

To make our daily bread,

Big Pharma took it over

To fill its banks instead

They filled it full of poison

To feed the growing crowd,

But how they call it progress

Is nothing to be proud.

There’s an army down below us

That works beneath our feet,

It has a balanced system

To make out food complete.

Things go round in circles

History tells us so,

Carbon is not something new.

Take a look in the hedgerows

Has no one ever seen

Nature does not grow in pretty rows

With nothing in between.

When we talk about our soil

Let’s think about our health

Not just bulging bank accounts and

Companies growing wealth.

The soil has the answer

Let’s treat it with respect,

Embrace our regenerative farming

And our planet will protect.

By David John Lievesley

djl@djlagriculture.co.uk