The Allerton Project, as a research and demonstration farm, has been in operation since 1992. We are, however, a part of the wider Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT), a membership organisation who have been conducting conservation science to enhance the British countryside for over 90 years. Today, the GWCT’s Farmland Ecology Unit carries out some of the most important research into nature friendly farming that is undertaken in this country, and is of international significance.

One of the jewels of GWCT research is the ‘Sussex Study’, the longest running monitoring project in the world that measures the impact of changes in farming on the fauna and flora of arable land. Since 1968, it has been conducted annually across 3200ha of land owned by the Duke of Norfolk on the Sussex Downs, between Arundel and Worthing. The starting point of the study was to determine the causes for the decline of the grey partridge, the iconic bird which forms the logo of the GWCT. Sadly, the British Trust for Ornithology recorded a drop in numbers of 91% between 1967 and 2010, a trend which has seen little national improvement in the past decade.

It was determined by the GWCT that the main reason for their decline was a reduction of chick-food insects in cereal crops caused by the disappearance of arable weeds such as the prickly poppy, cornflower and narrow-fruited knotgrass, given that such insects are the sole food source of recently fledged partridge chicks, which hatch in early-mid June. (In order to keep the dataset consistent, at least 100 sites (always arable fields) are monitored in the third week of June by hoovering up the invertebrates present with a ‘D-vac’). Ultimately, a lack of insect food was leading to the starvation of many hatched chicks, with the loss of arable weeds via agricultural intensification leading to the loss of both a habitat and a food source for those vital farmland invertebrates, the prime species of which are:

- Caterpillars (lepidoptera)

- Hoppers (homoptera)

- Bugs (heteroptera)

- Click beetles (elateridae)

- Sawfly larvae (symphyta)

- Leaf beetles (chrysomelidae)

- Weevils (Curculionidae)

- Ground beetles (carabidae)

The figures collected on the decline of these populations is stark; overall invertebrate abundance decreased by 37% across all taxa (a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms) with 47% of taxa in decline (and 16% increasing). Yet beneath those headline figures, the study shows that insect predator species declined by 67% on average, while crop pests increased by an average of 26% (if aphids are excluded, which actually recorded a 90% reduction in population size). Happily, in this study at least, pollinator populations remained broadly stable.

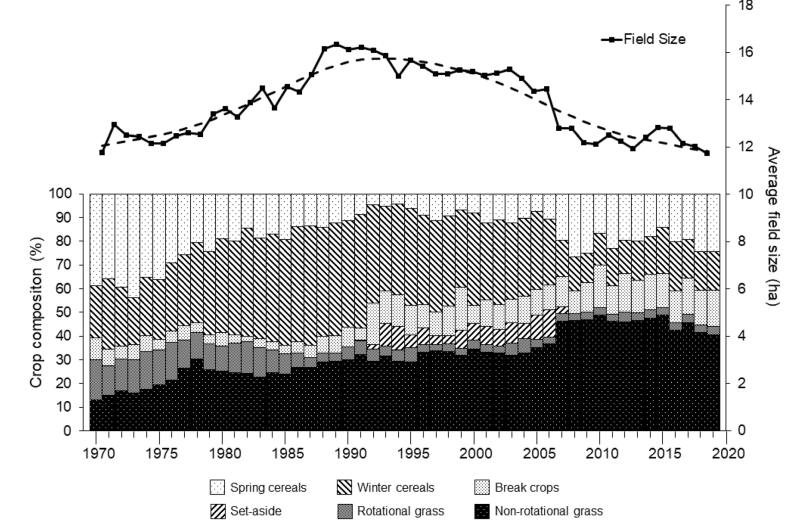

The data of the Sussex Study indicates that the majority of the invertebrate population decline occurred in the early decades of the work, and particularly in the 1970s, before stabilising (though still on a generally downward trajectory). This reflects the rapid and generalised intensification of agricultural land use in this period, much of which was captured by the GWCT in the form of field application records and land use. In the study area, as across much of the country, there was a marked decline of broader, more traditional rotations from 1970 as the area put down to spring crops and rotational grass declined, and the area of winter cereals increased along with average field size. There was also a general increase in the intensity of pesticide usage across the decades, largely in line with national trends. Although herbicide and fungicide use are currently at historically high levels across the study area, insecticide use peaked in the late 1980s, again in the mid-2000s, but has decreased significantly to the present day.

The GWCT has developed a metric called the ‘Chick Food Index’ (CFI) to determine the health of a population of farmland invertebrates to support a range of farmland birds. Different bird species will have a different CFI, but for grey partridge the figure is 0.7 – i.e. we need to see an invertebrate population of 0.7 to enable a grey partridge colony to maintain its current size. Worryingly, in a recent GWCT survey of ten farms nationwide between 2018-2020 across hundreds of grass, arable and horticultural fields, in no situation did the CFI rise anywhere near 0.7. Perhaps even more concerningly, where the same process was repeated in a range of agri-environment margins, the same result was obtained. In short, we do seem to be facing a generalised decline in our insect populations, with all the implications that has for farmland ecosystems. This is a trend which we know is also being experienced globally, with a 1-2% reduction in invertebrate numbers being reported annually.

I would be the first to say that agriculture is not the sole cause of the decline of invertebrate biodiversity – and that even where it is largely to blame, farmers are only reacting to the pressures of a society which demands ever-cheaper food, but dislikes asking questions of it. However, with agriculture covering some 70% of the UK landscape, and the implications of the historic intensification of agricultural practices for all manner of farm wildlife being well established, it’s clear that we do have our part to play in reversing this downward trend. And here too GWCT research has something to say.

Although grey partridge numbers nationally have continued to fall since the 1960s (including in some parts of the Sussex Study area), in parts of the estate where extensive measures have been put in place to recover their populations we have seen a significant increase in numbers since the mid-2000s – alongside other species such as skylark, lapwing and linnet. Such measures include the creation of beetle banks and hedgerows to break up larger arable fields and encourage the development of invertebrate populations within them, the establishment of grass strips and unharvested, low-input conservation headlands around field edges, and the provision of supplementary feeding for farmland birds through the winter. It also includes establishment of bespoke wildflower mixes, such as the GWCT Advanced Wildflower PARTRIDGE Mix which has been extensively trialled and developed to deliver the best outcomes for farmland birds and invertebrates throughout the year. It contains more than 20 species, both annuals and perennials (and primarily native), and has the potential to last for a full decade if managed correctly. Insect abundance in this mix peaks after around six years.

Other GWCT research also points the way toward healthier invertebrate populations on farm, for example indicating higher populations of pollinators on farms which have adopted ‘regenerative’ farming practices – primarily wider, more diverse rotations and the establishment of pollen and nectar margins and legume-rich rotational options, as well as more sympathetically managed hedgerows with a greater profusion of flowers. At the Allerton Project itself, we are part of the Rothamsted moth monitoring network, and for the past thirty years we can demonstrate an increase of around 35% in our macromoth populations, while at the national scale there has been a decline of around 35% in the same time period. This we have managed at the same time as retaining our core identity as a productive, ‘conventional’ and primarily arable farm. It’s also well established that many invertebrates – such as carabid beetles, which can play an importance role as crop pest predators – live part of their lifecycle in the soil, and therefore reduced tillage can play an important part in enhancing such populations.

The new options available to support Integrated Pest Management (IPM) via the Sustainable Farm Incentive (SFI) will do much to help many farmers think more carefully about farm invertebrate populations, but it must also be recognised that insecticide and herbicide use is only one part of the picture, and that the broader scope of SFI and other potential income streams must be utilised to build up the ‘green infrastructure’ needed across a farm to start to build beneficial insect populations. Simply going ‘cold turkey’ on inputs is likely to lead to decreased yields and disillusionment. That’s why the Allerton Project has put together a practical guide for farmers – ‘A guide to insect-rich farmland habitats’ – which is available online, and we are always open to groups of visitors to come and see some of the work which we have undertaken in our living lab landscape over the past 32 years.