If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

An introduction to soil health management

Anglo American exhibited their natural mineral polyhalite fertiliser ‘POLY4’ and Soil Scientist, Kathryn Bartlett gave a talk on how long-term soil management plans can improve soil fertility.

You will have heard it many times already how fundamental soils are to the wellbeing of our planet. Intrinsically knowing the value of good soil-based understanding, is the foundation of any growing system (excluding of course aquaponics!). Agriculture is recognised more and more as one of the drivers of possible mitigation of climate change, and as an industry with vast hectares of land on which significant gains could be achieved. Farmers are ever more increasingly expected to provide services in keeping with enhancing soil productivity and health. The job remit is massive: produce more and better-quality crops, with limited good quality soil and do that in an environmentally responsible manner. No small ask.

One of the major challenges we face in addressing soil productivity and health is the inherent variability of soils. The UK alone has hundreds of different soils and the landscape variation within field can be significant, affecting the management needs of this land. Therefore, ‘one size fits all’ solutions will not work, and we must rely on more detailed understanding at an appropriate scale to the management need, this is further hampered by soil data often being held by several institutions and not always readily available depending on your location.

The story is further complicated when we seek clarity on what is ‘soil health’ and what measurements can conclude this. The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations Intergovernmental Technical Panel on soils defines it as: ‘The ability of the soil to sustain the productivity, diversity, and environmental services of terrestrial systems’ which of course means that it is a dynamic concept changing with the anthropogenic drivers on that land.

Soils need to be considered in three dimensions – look beyond the surface at a complex world and intersection between physics, chemistry, and biology. Soil structure and texture regulate pore spaces, aeration, and drainage. Whilst clay particles in your soil regulate the nutrient availability along with soil organic matter which plays many other important roles such as gas exchange and affecting water movement in soils. Not forgetting that soils are one of the most biodiverse terrestrial systems – they are the recycling centre of the earth driving much of the resource we need to provide good quality food. However, with a third of global soils classified as degraded we are at greater risk of reduced production, not only in terms of volume, but in nutritional quality. Fertile productive soils form the basis to achieving this. Therefore, practices that reduce erosion, minimise soil organic carbon loss, correct nutrient imbalances, combat soil acidification, halt and remediate contamination and prevent soil compaction are some of the practical measures we can put in place to combat this.

To add one last complication to the thinking, we need to also consider soil management as a medium to long-term view when we are framing it within the lens of agrifood systems. Soil processes and changes happen over a scale of years and better to watch the long view to truly gain insight as to the management impacts on any given piece of land.

Whilst there is no single solution to addressing soil fertility problems, we now have many tools on hand to help. Focusing on providing the best physical, chemical, and biological conditions is the key to maintaining a more balanced and resilient soil system in the long term to provide increased functionality.

Things to keep in mind:

- Keeping the soil covered as much as possible to help prevent erosion losses.

- Selecting cover crop mixes with differing plant rooting structures to aid water infiltration and compaction zones.

- Keep soil trafficking to a minimum to avoid soil compaction.

- Where possible try to increase soil organic matter inputs.

- Provide balanced nutrition to ensure no harmful effects on soil pH and chloride levels.

- Regularly monitor your soils (visually and chemically) and keep a record to monitor long term trends.

Kathryn Bartlett is a soil scientist who is working on unpicking the interactions between polyhalite and soils. Building up this understanding of interactions will unlock new and innovative crop nutrient solutions as part of a global need to improve soil health/ performance that enhances crop nutrient use efficiency and land management practices. Kathryn holds a PhD in Soil Microbial Ecology of arable agricultural systems from the National Soils Resources Institute at Silsoe, Cranfield University. She has worked on projects ranging from nutrient cycling in northern peatlands through to helping inform UK soils policy. She is an honorary member of the British Society of Soil Science.

-

Grange Machinery

Strip-Till Preparator

The Preparator has been designed from carefully listening to farmers over the past few seasons who are wanting to perfect their establishment of maize. The layout of our three independent rows of cultivation discs that can be hydraulically adjusted whilst working in harmony with our low disturbance tine and point allows us to create a perfectly cultivated row that is ready for a seed to be planted into. This system is then finished with a zonal Guttler prism roller ring that is the final part of the cultivation pass to breakdown any clods that have flowed through the system as well as consolidating the row in readiness for a planter when the time suits to sew.

One of the unique features that the Preparator offers is the option of applying either granular or liquid fertiliser behind the loosening tine in preparation for seed to be placed into the row.

Low Disturbance LoosenerThe LDL has been designed with the need of farming practises moving towards direct drilling or min-till and the requirements that the latest direct drills have to sew into a level and perfectly finished surface. Compaction is commonly found at depths of 6″- 10, the Low Disturbance Loosener will be used to lift at full width and at depths of up to 12″. It is used primarily to loosen the soil structure straight after combining and removing the compaction pan. We have witnessed farms start to experience poor crop establishment and growth due to the compaction generated from machinery traffic, rain fall etc. We offer the central folding machine in 4m along with the wider working widths of 5m & 6m.

6m Low Disturbance Toolbar

Options…..

The 6m LDT offers the ability to lift and lower the cultivating legs and discs within the frame/chassis whilst not interrupting the height of the trailed implement on the rear hitch. This feature allows the machine to be mounted on the tractor and to only be used when required. The operator has complete control on having the loosening legs in or out of work whilst on the move, this allows the leg and disc depth to be altered if required without leaving the cab. One of the key attributes of the machine is that it provides options for the farmer.

‘Tight Turn’ – Automatic Headland Turning Feature…The 6m LDT offers a unique system that allows the machine to be converted from 6m working width down to 3m during headland turns. This feature eliminates the need for an extended headland, the wings on the machine automatically lift to a 90 degree position whilst the operator concentrates on performing the turn, this is achieved using one tractor auxiliary service. The wings will then unfold and become a 6m beam again ready for the next pass, a very easy but versatile feature that transforms field operations.

Choose your system…

The 6m LDT has proven to be a very popular machine that is used with a range of trailed implements. Having the ability to lift and lower the cultivating legs when in combination with other implements without affecting the trailed setup makes the machine very versatile and to be frequently used. The LDT adds a loosening system to machines that are already on farm allowing farmers to enhance their current cultivation and drilling system. We offer three widths of Low Disturbance Toolbar in 3m, 4m & 6m

Heavy Duty Track Eradicator

This machine is very popular for farmers that are currently practising or looking to move into CTF however it is aimed at eradicating wheelings in all farming practises. A strong and robust frame that is built with 8m – 12m trailing implements in mind. The versatility and ability in having the loosesning legs in/out of work is a key feature of the machine. The front cutting discs are on the same service which means the machine is very easy to operate and can be set up in the headland management screen. The machine replicates the tractor drawbar height, allowing you to lift and lower the wheel eradicator legs whilst on the move, without affecting trailing implement setup.

Set your trailing implement to the optimum working depth and let the Track Eradicator take care of your wheelings.

-

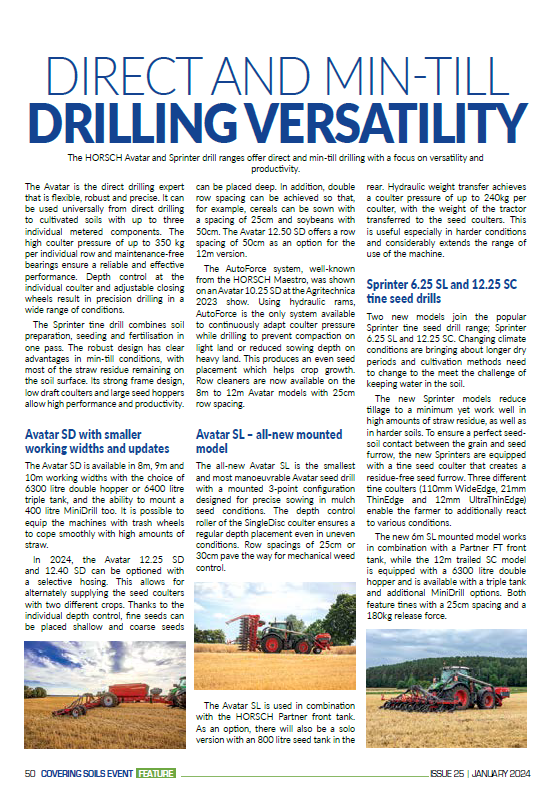

Direct and min-till drilling versatility

The HORSCH Avatar and Sprinter drill ranges offer direct and min-till drilling with a focus on versatility and productivity.

The Avatar is the direct drilling expert that is flexible, robust and precise. It can be used universally from direct drilling to cultivated soils with up to three individual metered components. The high coulter pressure of up to 350 kg per individual row and maintenance-free bearings ensure a reliable and effective performance. Depth control at the individual coulter and adjustable closing wheels result in precision drilling in a wide range of conditions.

The Sprinter tine drill combines soil preparation, seeding and fertilisation in one pass. The robust design has clear advantages in min-till conditions, with most of the straw residue remaining on the soil surface. Its strong frame design, low draft coulters and large seed hoppers allow high performance and productivity.

Avatar SD with smaller working widths and updates

The Avatar SD is available in 8m, 9m and 10m working widths with the choice of 6300 litre double hopper or 6400 litre triple tank, and the ability to mount a 400 litre MiniDrill too. It is possible to equip the machines with trash wheels to cope smoothly with high amounts of straw.

In 2024, the Avatar 12.25 SD and 12.40 SD can be optioned with a selective hosing. This allows for alternately supplying the seed coulters with two different crops. Thanks to the individual depth control, fine seeds can be placed shallow and coarse seeds can be placed deep. In addition, double row spacing can be achieved so that, for example, cereals can be sown with a spacing of 25cm and soybeans with 50cm. The Avatar 12.50 SD offers a row spacing of 50cm as an option for the 12m version.

The AutoForce system, well-known from the HORSCH Maestro, was shown on an Avatar 10.25 SD at the Agritechnica 2023 show. Using hydraulic rams, AutoForce is the only system available to continuously adapt coulter pressure while drilling to prevent compaction on light land or reduced sowing depth on heavy land. This produces an even seed placement which helps crop growth. Row cleaners are now available on the 8m to 12m Avatar models with 25cm row spacing.

Avatar SL – all-new mounted model

The all-new Avatar SL is the smallest and most manoeuvrable Avatar seed drill with a mounted 3-point configuration designed for precise sowing in mulch seed conditions. The depth control roller of the SingleDisc coulter ensures a regular depth placement even in uneven conditions. Row spacings of 25cm or 30cm pave the way for mechanical weed control.

The Avatar SL is used in combination with the HORSCH Partner front tank. As an option, there will also be a solo version with an 800 litre seed tank in the rear. Hydraulic weight transfer achieves a coulter pressure of up to 240kg per coulter, with the weight of the tractor transferred to the seed coulters. This is useful especially in harder conditions and considerably extends the range of use of the machine.

Sprinter 6.25 SL and 12.25 SC tine seed drills

Two new models join the popular Sprinter tine seed drill range; Sprinter 6.25 SL and 12.25 SC. Changing climate conditions are bringing about longer dry periods and cultivation methods need to change to the meet the challenge of keeping water in the soil.

The new Sprinter models reduce tillage to a minimum yet work well in high amounts of straw residue, as well as in harder soils. To ensure a perfect seed-soil contact between the grain and seed furrow, the new Sprinters are equipped with a tine seed coulter that creates a residue-free seed furrow. Three different tine coulters (110mm WideEdge, 21mm ThinEdge and 12mm UltraThinEdge) enable the farmer to additionally react to various conditions.

The new 6m SL mounted model works in combination with a Partner FT front tank, while the 12m trailed SC model is equipped with a 6300 litre double hopper and is available with a triple tank and additional MiniDrill options. Both feature tines with a 25cm spacing and a 180kg release force.

-

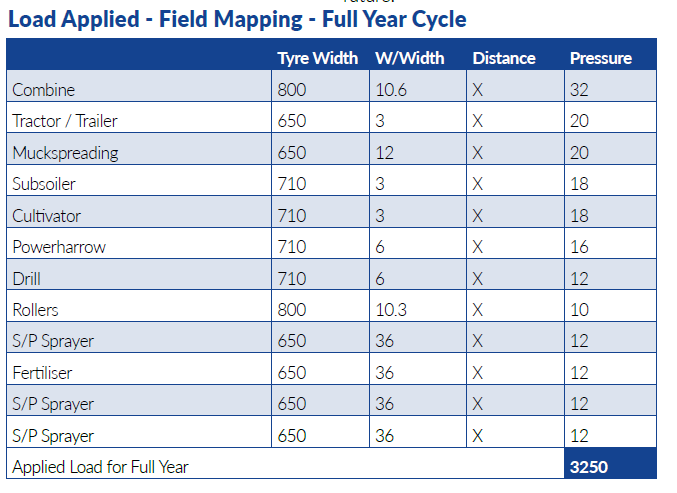

Tyre & Compaction – Covering Soils Day

The Tyre & Compaction presentation hosted by Philip Wright & Stephen Lamb was an engaging and well-attended station during the event.

From a tyre perspective, the focus was very much on the Interface – the contact area between soil and tyre, and how by doing some homework, soil compaction could be dramatically reduced. Identifying the most suitable size of tyre for the application, with the aim of selecting the lowest operating pressure tyre within that size, which normally would be VF specification tyre, with many of the guests already benefiting from that fitment.

A demonstration was given to show, how in some cases, it can be more beneficial to go longer in the footprint, rather than just going wider, this is where VF technology can really play its part, by having a longer footprint, within the already committed trackway, as opposed to just going wider.

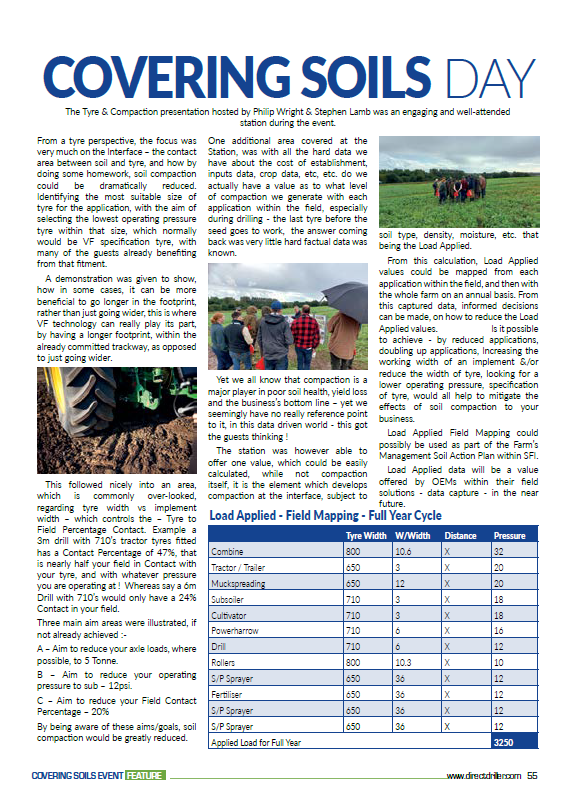

This followed nicely into an area, which is commonly over-looked, regarding tyre width vs implement width – which controls the – Tyre to Field Percentage Contact. Example a 3m drill with 710’s tractor tyres fitted has a Contact Percentage of 47%, that is nearly half your field in Contact with your tyre, and with whatever pressure you are operating at ! Whereas say a 6m Drill with 710’s would only have a 24% Contact in your field.

Three main aim areas were illustrated, if not already achieved :-

A – Aim to reduce your axle loads, where possible, to 5 Tonne.

B – Aim to reduce your operating pressure to sub – 12psi.

C – Aim to reduce your Field Contact Percentage – 20%

By being aware of these aims/goals, soil compaction would be greatly reduced.

One additional area covered at the Station, was with all the hard data we have about the cost of establishment, inputs data, crop data, etc, etc. do we actually have a value as to what level of compaction we generate with each application within the field, especially during drilling – the last tyre before the seed goes to work, the answer coming back was very little hard factual data was known.

Yet we all know that compaction is a major player in poor soil health, yield loss and the business’s bottom line – yet we seemingly have no really reference point to it, in this data driven world – this got the guests thinking !

The station was however able to offer one value, which could be easily calculated, while not compaction itself, it is the element which develops compaction at the interface, subject to soil type, density, moisture, etc. that being the Load Applied.

From this calculation, Load Applied values could be mapped from each application within the field, and then with the whole farm on an annual basis. From this captured data, informed decisions can be made, on how to reduce the Load Applied values. Is it possible to achieve – by reduced applications, doubling up applications, Increasing the working width of an implement &/or reduce the width of tyre, looking for a lower operating pressure, specification of tyre, would all help to mitigate the effects of soil compaction to your business.

Load Applied Field Mapping could possibly be used as part of the Farm’s Management Soil Action Plan within SFI.

Load Applied data will be a value offered by OEMs within their field solutions – data capture – in the near future.

-

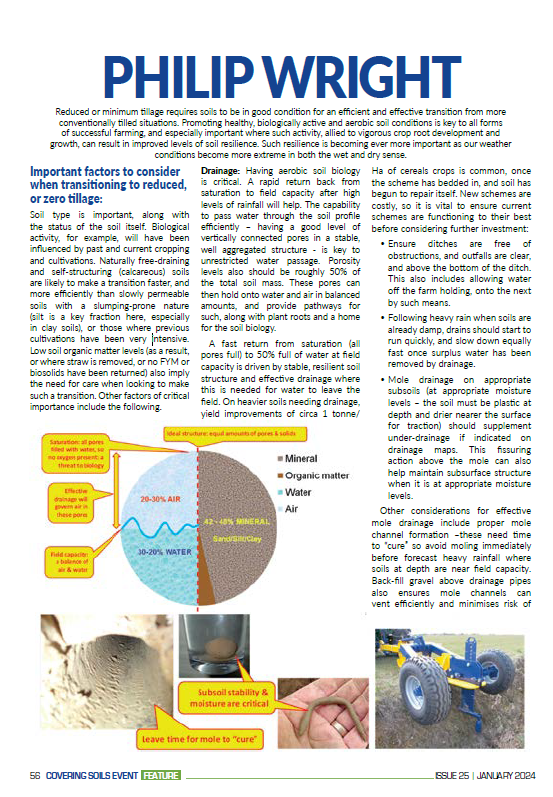

Tips for transitioning

Overview: Reduced or minimum tillage requires soils to be in good condition for an efficient and effective transition from more conventionally tilled situations. Promoting healthy, biologically active and aerobic soil conditions is key to all forms of successful farming, and especially important where such activity, allied to vigorous crop root development and growth, can result in improved levels of soil resilience. Such resilience is becoming ever more important as our weather conditions become more extreme in both the wet and dry sense.

Important factors to consider when transitioning to reduced, or zero tillage: Soil type is important, along with the status of the soil itself. Biological activity, for example, will have been influenced by past and current cropping and cultivations. Naturally free-draining and self-structuring (calcareous) soils are likely to make a transition faster, and more efficiently than slowly permeable soils with a slumping-prone nature (silt is a key fraction here, especially in clay soils), or those where previous cultivations have been very intensive. Low soil organic matter levels (as a result, or where straw is removed, or no FYM or biosolids have been returned) also imply the need for care when looking to make such a transition. Other factors of critical importance include the following.

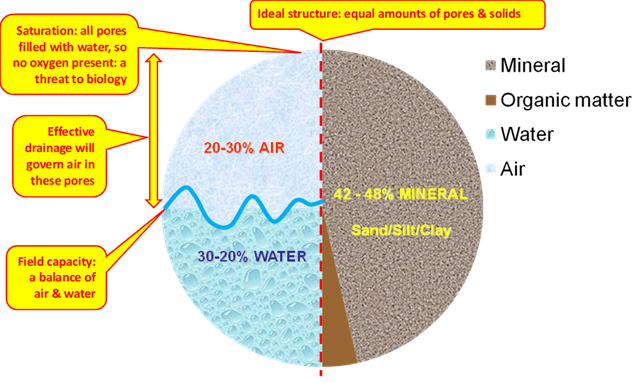

Drainage: Having aerobic soil biology is critical. A rapid return back from saturation to field capacity after high levels of rainfall will help. The capability to pass water through the soil profile efficiently – having a good level of vertically connected pores in a stable, well aggregated structure – is key to unrestricted water passage. Porosity levels also should be roughly 50% of the total soil mass. These pores can then hold onto water and air in balanced amounts, and provide pathways for such, along with plant roots and a home for the soil biology.

A fast return from saturation (all pores full) to 50% full of water at field capacity is driven by stable, resilient soil structure and effective drainage where this is needed for water to leave the field. On heavier soils needing drainage, yield improvements of circa 1 tonne/Ha of cereals crops is common, once the scheme has bedded in, and soil has begun to repair itself. New schemes are costly, so it is vital to ensure current schemes are functioning to their best before considering further investment:

- Ensure ditches are free of obstructions, and outfalls are clear, and above the bottom of the ditch. This also includes allowing water off the farm holding, onto the next by such means.

- Following heavy rain when soils are already damp, drains should start to run quickly, and slow down equally fast once surplus water has been removed by drainage.

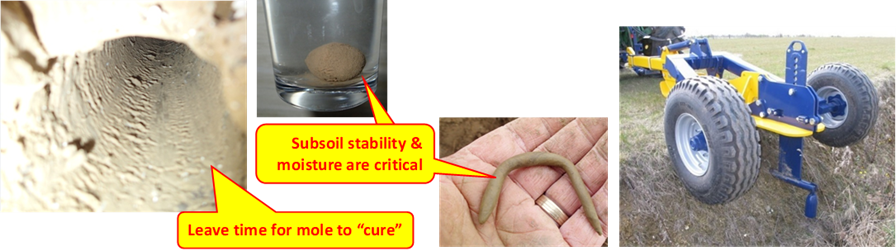

- Mole drainage on appropriate subsoils (at appropriate moisture levels – the soil must be plastic at depth and drier nearer the surface for traction) should supplement under-drainage if indicated on drainage maps. This fissuring action above the mole can also help maintain subsurface structure when it is at appropriate moisture levels.

- Other considerations for effective mole drainage include proper mole channel formation – these need time to “cure” so avoid moling immediately before forecast heavy rainfall where soils at depth are near field capacity. Back-fill gravel above drainage pipes also ensures mole channels can vent efficiently and minimises risk of premature collapse.

Attempting to direct drill poorly drained and poorly structured soils is a recipe for disaster.

Soil Structure: This also determines free root, water, and air passage. Barriers, if found, should be removed so effective rooting (and yield) can result. Soil structure resilience improves with biological and root activity, so significant compromises to yield (and crop rooting) will prolong the transition process, and have negative effects on the business bottom line. The spade is essential here to determine the degree of damage, if present, and actions then needed.

Soil loosening by low disturbance “soil profile stretching” should be considered if this improves rooting, and shallow drainage.

- In many cases, such structuring can be done by a tine based drill – for example when establishing a cover crop. Having the capability to drill seed slightly shallower than loosening depth can be good – as the BTT opener examples seen on Clive’s Sprinter drill.

- An option to use a loosener ahead of the drill can also be effective, where needed.

- Such loosening can often be timed ahead of a break crop such as WOSR or beans, allowing its effect to benefit the following first wheat also.

- Deeper structure issues are often confined to known areas (turning headlands, & on less stable soils) where a controlled “stretching” of the profile will usually then allow effective root development and drainage. This process is NOT subsoiling, and can be done by a “sward lifting” approach in conjunction with growing roots through the profile.

- Where this loosening action is needed, ensuring structured “columns” remain between the loosened zones will further stabilise the structure and help maintain the biology present. The benefit to yield in the example previously outlined was just over 1 tonne per hectare of spring barley where the compacted headland was restructured.

Cropping: Growing crops with effective root systems normally drives further, higher yielding crops to then follow. Such crops and roots support positive soil biology, soil resilience, and also sequester Carbon most effectively. Avoid leaving land fallow and without some form of a growing crop whenever possible will maximise the building of soil resilience.

Prevention before cure: Prevention, or mitigation of trafficking damage helps to minimise unnecessary cultivations, accelerating the transition.

- Controlling and managing traffic limits areas of damage – Controlled Traffic Farming principles apply.

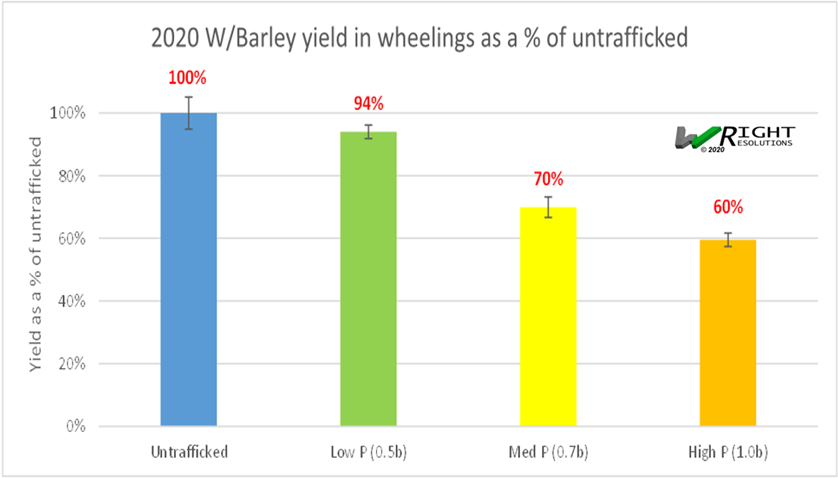

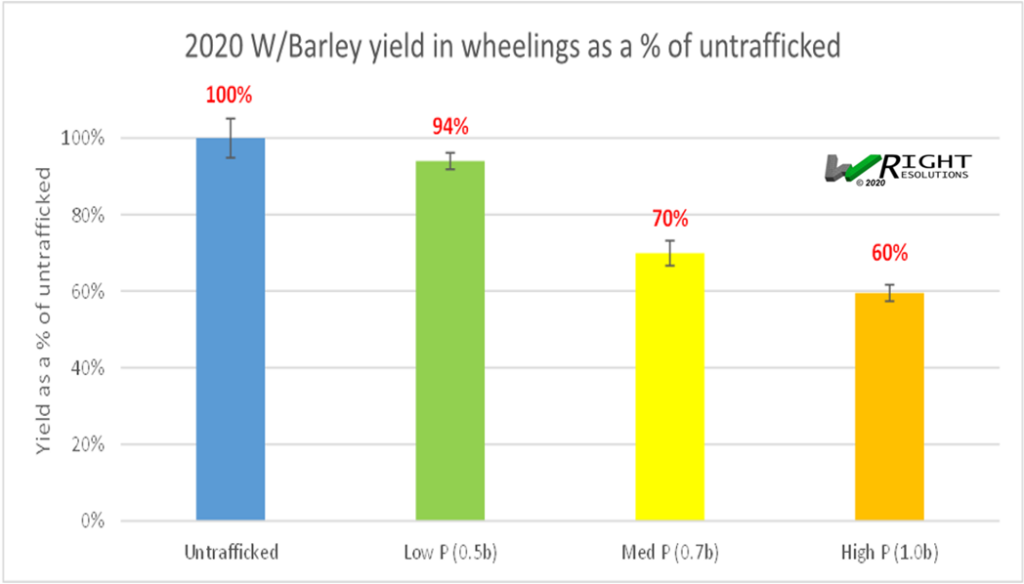

- Minimising axle loads, and ground pressures resulting, is a key factor to consider when transitioning. Many disc based direct drills do not use eradicators, and in any event, keeping ground pressures to levels of 0.7b or below will minimise adverse yield effects in these trafficked zones. Yield effects from ground pressure vary, and can lead to yield reductions of 40% or more, compared to where not trafficked, when drilling direct.

Above: typical crop yields (compared to where untrafficked) in drill tractor trafficked areas: a mean of 4 seasons of work across 2 soil types (light & heavy) where cereal crops have been direct drilled.

-

Direct Driller Issue 24 Contents

Farmer Focus – Phil Rowbottom

Jan 2025 It’s been a while since I last wrote a Farmer focus article in…

For The Love of Soil…

For a generation, farmers have taken for granted their most valuable resource, often considering it…

Getting a grip on phosphorus

Written by Tim Stephens NSch, Catchment Management Specialist, Wessex Water A vital element Phosphorus (P)…

Soil Winter Blues

Unmoved stubbles can often be the driest land on the farm after heavy rainfall. Yet…

Unlocking the power of soils

Three practical days featuring US soil biology researcher Dr Elaine Ingham about unlocking the power…

Balancing Wildlife and Farming at Lower Pertwood Farm

Written by Nick Adams, Wildlife Consultant, Lower Pertwood Farm The winds of change are blowing…

Cover crop champion update

A network of cover crop champions is providing a practical view on the impact of…

We’re changing how we manage the Claydon farm

In a political environment where farming is battling increasing headwinds, Suffolk arable farmer and inventor…

TFF Direct Drill Demo day 2025

10 years ago now in the early days of TFF we ran a trial here…

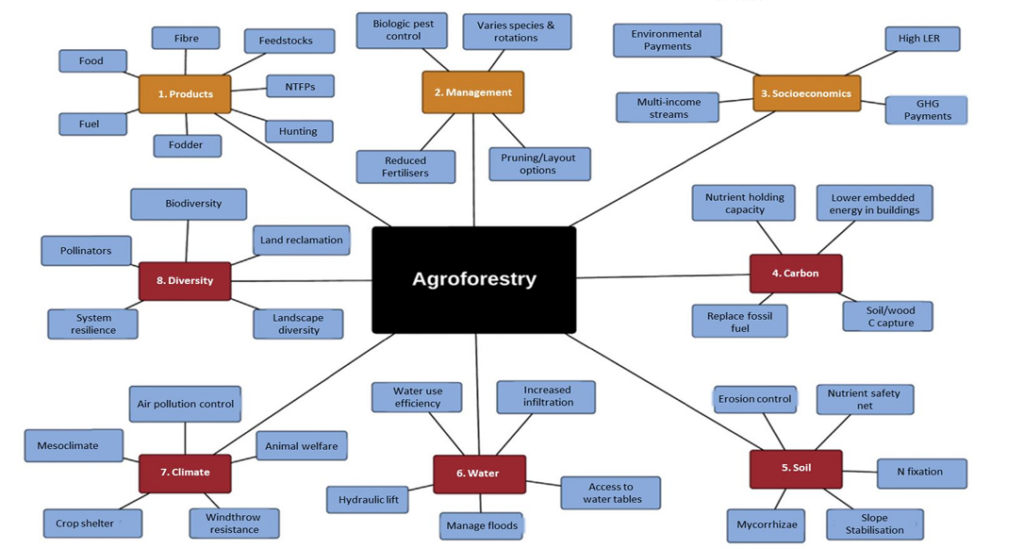

Agroforestry options

Dr David Cutress: IBERS, Aberystwyth University. Agroforestry is receiving a lot of focus for its…

The top five things to do this winter

To aid landowners and farmers with their 2025 planning, Knight Frank’s Andrew Martin and Mark…

Farmer Focus – Tim Parton

Another year, another set of problems? I can only feel at the time of writing…

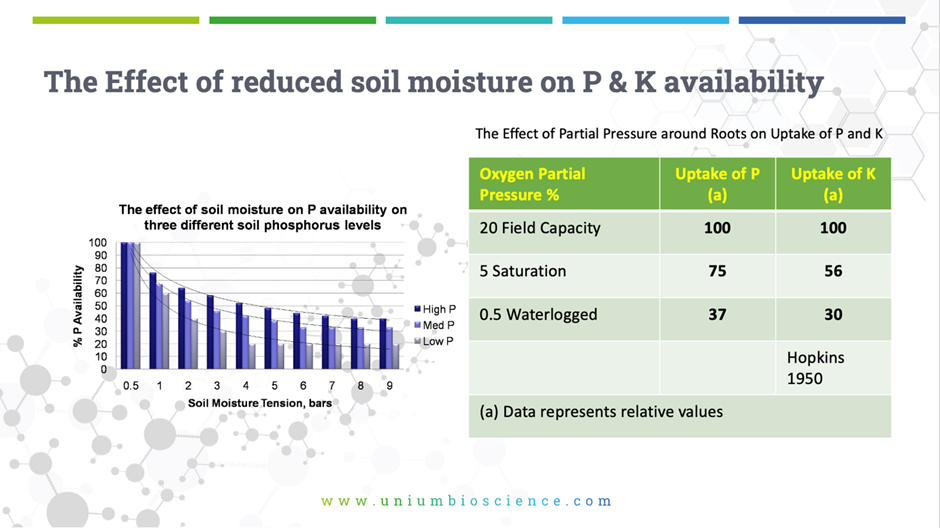

Smart phosphorus management to boost yields in depleted soils

WRITTEN BY JOHN HAYWOOD – UNIUM BIOSCIENCE Standfirst: Environmental conditions play a significant role in…

Humic Substances: a background to their classification, properties, origins and uses in Agriculture.

Written by Tim Smales from Humi-Cert.com Humic substances play a vital role in a healthy…

Plan ahead to get the most from soil sampling

Soil sampling is an essential tool in understanding the nutrient availability of soils, but unless…Farmer Focus – Billy Lewis

Dec 2024 Another tough year of compromises, setbacks and stress, all as a direct result…

Two RAGT wheats gain full UK approval on AHDB’s 2025/26 Recommended List

Breadmaking wheat RGT Goldfinch and soft wheat RGT Hexton made the list after a very…

Planning for silage success 2025 – using AgTech to fine tune decision making.

Improving quality and producing the right quantity for the animal numbers on farm takes planning…

Ecoacoustics – a new underground horizon for soil health

Following on from a farm trial undertaken by Andy Cato’s Wildfarmed farms, (as mentioned in…

Farmer Focus – John Cherry

Well, 2024 was a bit rubbish on the farm. We didn’t get all our planned…

Potato cyst nematodes (PCN): The hidden enemy of potato crops

PCN damage to potatoes Potato cyst nematodes (PCN) are a major threat to the UK…

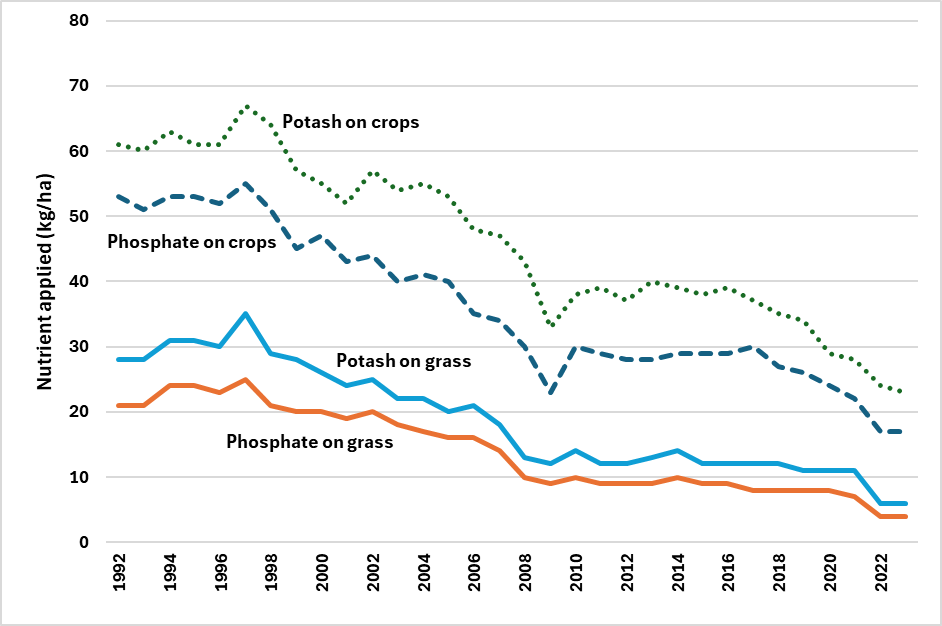

Long-term fall in phosphate use raises concerns

The development of soil-release agents and protected forms of phosphate means growers can meet crop…

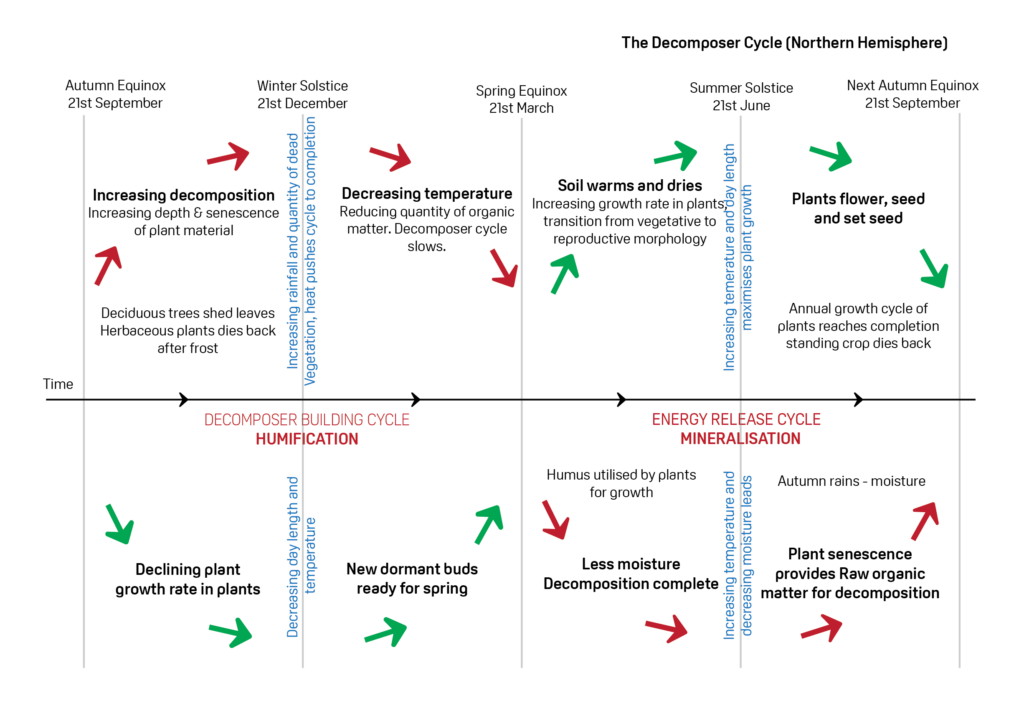

The importance of the winter decomposer cycle

Written by Mike Harrington, Managing Director of AIVA Fertiliser Following on from the beginning of…

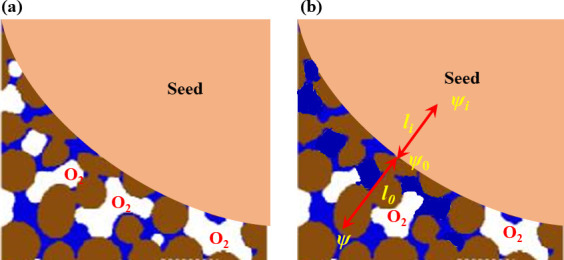

New seed germination model devised

New research from Rothamsted Novel tool will give breeders more predictive accuracy for seed development…

Worcestershire-based family business wins industry award

Chadbury-based agricultural machinery manufacturer, Weaving Machinery, has been awarded Gold in the British and Irish…

Welcome to the first tech focussed edition of Direct Driller Magazine. From now on, issues will rotate between soils issues and tech issues.

Contents –

Old-fashioned farming with modern technology – page 4.

It’s 2030, so how have we done? – page 4.

Labour pains push robotic pickers – page 6.

Industry-leading research in robotics and automation – page 12.

Flash, crackle, pop – page 14.

Agronomist in Focus – Todd Jex – page 16.

The win-wins of regenerative agriculture – page 19.

Robots find their way into farmers fields – page 22.

Bayer and Microsoft forge a new frontier – page 26.

Robitics and perception in agriculture – page 28

What will appear at FIRA24? -30

Farmer Focus – Thomas Gent – 36

From hands-free hectare to aerial delivery – 37

Farmer Focus – Daniel Davies – 39

Catapult plans for UK agritech – 41

Shedding light on LED grow lighting – 46

Drilling down into fixed costs – 48

Farmer Focus – Simon Beddows – 50

Making methane practical – 52

Hitting rock bottom – 53

Basics best for hi-tech wine – 56

Biochar venture wins equity investment – 59

Farmer Focus – Clive Bailye – 61

Manufacturer Focus – Vaderstad – 63 -

Old-Fashioned Farming with Modern Technology

I first encountered this definition of Regenerative Farming about a year ago, and it struck a chord with me. Farmers talk (often nostalgically) about farming again like their grandfather used to, but while that is true in the approach, the method has changed massively. Technology has played a pivotal role in enabling regenerative practices to evolve on an unprecedented scale, and scientific studies have deepened our understanding of soil dynamics.

Reviewing Direct Driller Magazine over the past six years reveals a consistent blend of soil-focused content and technological advancements. Building on this foundation, we have decided to take our exploration further. Future magazine issues will alternate between technology and soils, allowing for in-depth discussions on each topic. Our approach, coupled with the launch of Groundswell in 2016, has profoundly shifted the perception of Regenerative Farming in the UK and increased its visibility throughout the supply chain. This shift is now being recognised with higher commodity prices.

In the realm of technology, our aim is to provide farmers with increased exposure to developments in the UK and around the world. This involves identifying areas for incremental advances and contemplating more extensive changes, envisioning what a modern farm might look like in the next two decades.

We often hear the assertion that “farming is changing”, but the crucial question is: changing to what? We hope that the Tech Farmer issues will assist farmers in understanding how to steer their businesses towards greater profitability and sustainability. Even if certain aspects of their farms undergo significant transformation, these changes will contribute to a more robust and adaptive agricultural sector.

Considering the constant evolution in farming practices, the average farmer in 20 years might be quite different. It prompts us to reflect on our own evolution compared with our parents and wonder whether we really anticipate farming for our children will be that different.

-

It’s 2030, so how have we done?

Tom Allen-Stevens travels forward to 2030 and imagines what prospects agri-tech pioneers will have.

In just a few days it will be 2030 – for over a decade, this has been seen as something of a milestone year in farming’s journey to Net Zero.

It also seems a good point to look back on the first issue of Tech Farmer, that was launched just before Christmas 2023. What were the key issues we picked out then, and how have they developed since?

2023 was the beginnings of the Fourth Agricultural Revolution – a time at which it was first recognised (at last) that farmers are innovators as well as capable practitioners. The Basic Payment had reduced to half its original offering, and uncertainty surrounded how SFI would replace it.

No one had ever heard of ADOPT, the new Defra-funded scheme that’s now credited for helping pioneering farmers bring new research into practice. Or at least no one had heard of it until Tech Farmer became the first to announce its arrival (right there on p42 of our first issue, if you have any doubts).

Interesting too that this was announced in the same article that explored the merger of the Agri-Tech Centres and the formation of what then became the Agri-Tech Catapult. Who would have thought back then that these centres would subsequently merge with AHDB?

Robotics was the focal point of that inaugural issue, and the cover story profiled for the first time what was then the relatively unknown potential of CLAWS – Concentrated Light Autonomous Weeding and Scouting (p12). Of course, things have now moved on – it’s incredible to think how much we used to rely on glyphosate for weed control.

And do you remember those pre-emergence herbicides we used to apply with gay abandon, until weed resistance rendered them obsolete and regulators decided they’d had enough? Thank goodness for the pioneering solutions that have developed since, some of them shown at FIRA 2024 (p28).

One thing that struck me, looking back at that first issue, was Jonathan Gill’s insight into what the next ten years would bring (p35), given his experience as one of the heralds of the hands-free hectare.

“My future hope is a flock of drones performing tasks across the fields, all self-launched and tasked by an AI field manager who knows the best conditions day or night to plant or protect crops even down to a single plant,” he says. Wow – just remember, he talked of that at a time when UK regulation made such a hope unthinkable. Thank goodness policy makers took note.

To be fair, that’s one aspect that the agri-tech pioneer of 2030 can be grateful for – the foundations for agri-innovation may have been laid down by the last Tory government (remember them?), but it’s the Coalition that needed to step up to the task, and to be fair it did soon after the General Election in 2024. I certainly can’t remember as much being invested in farmer-led R&D. And its ag policy is clearly proving to be a vote winner, if the recent GE2029 landslide victory for the new Labour administration is anything to go by.

The European picture is now a similar scene of good prospects for those farmers who have grasped the technology nettle and worked to shape it to their advantage. The EU New Horizon for Agriculture Agenda, signed after the end of the Ukraine conflict, at last gave the green light across Europe for gene-edited crops, and put the emphasis squarely on productivity, as the previous Farm to Fork Strategy was quietly dropped. Analysts reckon the policy move aligns the EU much closer to the UK’s current agri-tech tract. This explains why some of the businesses we profiled in that first issue of Tech Farmer are expanding rapidly across the EU.

The global picture has been more of a rocky road, however. UK farmers may have benefited from the soya crisis of 2024, but the economic turmoil in South America that ensued has sent shock waves of uncertainty throughout the global ag industry. We’ve yet to see whether the US president can deliver in her second term of office the promises to support US Agriculture she made in her first, but the impact, in terms of agri-tech investment, is already being felt.

Nowhere was this more obvious than in the halls of Agritechnica 2029. Visitors to the show just six years earlier were treated to innovations such as New Holland’s energy-independent farm (p50) and John Deere’s Farm of the Future. The worry then was that the developments into autonomy and tech made by these global giants wouldn’t be available to UK farms, with our small roads and fields. The UK was in danger of being marginalised out of agri-innovation directed purely at the vast fields and wide, open plains of the Americas and Eastern Europe.

But many who took the treck to Hanover last month were disappointed to find such tech hadn’t moved on as much as had been promised – mutterings of ‘emperor’s new clothes’ were not uncommon. What’s now more likely, according to analysts, is that the investment needed to bring it to market melted away with the confidence in Big Ag, triggered by the soya crisis – whatever happened to the agricultural partnerships promised by the likes of Google, Amazon and Musk?

What Big Ag failed to recognise was the importance of involving farmers in developing that tech, and now those companies are paying the price. It was to represent the interests of those pioneering farmers that Tech Farmer came into being. We had seen how Direct Driller had gelled the interests of those pioneering a path in regenerative agriculture. It was time to bring those interests together with farmers from other sectors. To become a focal point for the surge of interest in agri-tech. To explore the fascinating and fast-developing realms of new tech, of AI, autonomy, of their possibilities to reshape how we farm.

But most of all it was to represent the interests of those who were resolved to shape it. To tell the stories and share the experiences of the farmers at the cutting edge of the Fourth Agricultural Revolution. Because, as we now know, this new chapter in farming’s progression belonged to you. You implemented the innovations, breathed the life and the opportunity into the new tech.

So it’s largely thanks to you that with just a decade to go, UK Ag is now well on track to deliver Net Zero – Happy Christmas and here’s to a prosperous 2030.

Tom Allen-Stevens farms 170ha in Oxfordshire and leads the British On-Farm Innovation Network (BOFIN).

-

Labour pains push robotic pickers

Labour shortages are driving fruit and veg producers to examine robotic solutions. Tech Farmer attends the World Agri-Tech Innovation Summit in London to find out more.

Increasingly difficult to find and ever more costly. It’s little wonder that some of the UK’s most innovative farms and businesses are choosing to investigate and invest in the potential of robotics, rather than relying solely on manual labour.

“The reality is that it has become increasingly challenging to source seasonal labour in the UK,” says David Sanclement, Group chief executive officer of The Summer Berry Company.

The firm grows strawberries, blueberries, blackberries and raspberries across 200ha in the UK, including 24ha in glasshouses, and mostly raspberries on 190ha in Portugal. “Our core market is the UK, and we serve most of the major retailers, including Tesco, Marks and Spencer, Waitrose and Asda. We also supply European retailers like Carrefour, Rewe and Aldi.”

With no immediate prospect of the labour market becoming easier, the business has a vision to reduce its dependence on seasonal labour. Robotics is one area it is investigating, although David stresses he doesn’t see robotics as a complete replacement for labour.

“It could be useful in a number of situations,” he explains. “Most notably, using robots to forecast and potentially to provide a night shift, which is currently not attainable for our workers.

The Summer Berry Company has 54 Tortuga AgTech robots, currently used to replace night shifts or tackle fields where labour is not available. “In the longer term, we hope the use of robotics will support our labour needs eventually meaning less seasonal workers. It would be more efficient to have a stable year-round workforce with the robots supporting at peaks of harvest.”

Another important advantage for the use of robots is through better forecasting capabilities, David adds. “This is important to us. We work with historical trends, relying on the expertise of our agronomists and weather forecasts, but with the addition of data coming from the robots we have better forecasting accuracy of when to pick.”

Improved harvest data forecasting brings a couple of advantages for the business, David says. “One, it gives us an opportunity to forecast our labour more efficiently. If you can predict very accurately when you’ll need to harvest the fruit, the difference between one week and another, you can optimise your labour in a better way.

“And two, you might achieve better returns with the supermarket. A retailer will be keen to receive information three weeks ahead rather than two days because it gives them a better opportunity to plan promotions or to plan strategically to allocate your fruit onto the shelf.”

Each machine uses advanced artificial intelligence to help with key decision making required to harvest the fruit. The Summer Berry Company trials with robotics start-up Tortuga AgTech began in 2018, with pick quality and picking speed the two most important criteria success was going to be judged on.

“This is a journey,” David says.

The business started comparing robots to the best picking performance but quickly realised it should be comparing them to the poorest picking performance. “AI and software are constantly improving, so you need to start from the bottom and progressively raise standards.”

Picking speed has also improved significantly over the past three years, although generally it is still not as good as human labour. That doesn’t matter that much with David looking at his current 54 Tortuga AgTech robots to replace night shifts or tackle fields where labour is not available.

Eric Adamson stresses that providing a harvesting service first is key as it creates immediate value for the grower. The purpose-built and designed robots are cart-sized four-wheel machines that can work either inside or outside, with two arms that operate autonomously, explains Tortuga AgTech chief executive officer and co-founder Eric Adamson.

Each machine uses advanced artificial intelligence to help with key decision making required to harvest the fruit. “The most important thing you teach a human picker on their first day is which fruit to pick and which to leave,” Eric says.

“Most of the management time after that is whether the workers are doing that right? Are they picking red ones and not the pink ones, or are they picking the pink ones that look red enough? That’s actually losing yield for the farm and it’s not as good quality for the supermarket.

“Team leaders at The Summer Berry Company focus on performance, quality and speed. We need the same focus with the robots.”

The robots run 17 machine learning models at any given time to help make those sophisticated decisions – where and how to drive, where and what to pick, and whether to pick or not. It’s also collecting a bunch of data about the crop’s growth at the same time, Eric says.

While the latter is an important add-on service, Eric stresses that providing a harvesting service first was key as it creates immediate value for the grower. “Help to solve the hardest problem first and then add the other things.”

Customer service is another key requirement. “We provide a full service to the farm,” Eric says.

That was important and a significant change, David adds. “I’ve worked with some other companies doing robotics and not all of them were able to offer service. Having a number of Tortuga members working at The Summer Berry Company makes a big difference if the robot is not working.”

Barfoots target automation

High value vegetable crops are also fundamentally labour intensive making them a logical target for automation, says Keston Williams, chief operating officer of Barfoots. But some are much easier than others to automate.

His firm grows around 3400ha of various vegetable crops in the UK. “The vast majority of the area is sweetcorn, followed by tenderstem broccoli, courgettes, asparagus and green beans.”

Like other farm businesses in vegetable and fruit production, accessing labour has become more challenging following Brexit. “I don’t see that getting any better any time soon, and it’s certainly continued to get more and more expensive, so we’re looking for solutions that allow us to reduce labour and improve efficiency.”

In some crops, such as sweetcorn and green beans a fully automated system for the crop is in place, in terms of machines for harvesting, grading and packing.

“In green beans we’ve taken it from a team of what would now be 400 people harvesting green beans to a team of 12 because it’s automated.

“But for the sustainability of growing UK premium veg crops, we need to consider how we’re going to automate the majority of our crops.”

But what makes a crop like sweetcorn relatively straightforward to automate – it’s a single destruct harvested crop – is the exact opposite for crops like courgettes and tenderstem broccoli.

“With courgettes we have to go into the field maybe as many as 25 times to harvest or graze it over a period of time. It’s not a destructive harvesting process, so therefore you need to look after the crop when you harvest. Tenderstem broccoli, rhubarb and asparagus are the same – multiple passes of the same crop.

“Secondly, you also need the dexterity that’s required to pick the crop – see the fruit, or flower in the case of tenderstem broccoli, and then pick it at the right point.”

The image processing involved in that to decide on the spot whether to harvest now or leave it for another two days to mature, or if then it will be over mature, plus then the dexterity to pick it and put it in the right container are decisions the human brain can make quickly and with great accuracy. “They’re much more difficult to replicate on a robotic basis.”

For a while Barfoots put those requirements in the too difficult to overcome box, but advances in artificial intelligence and image recognition have brought it into the realm of the possible, Keston suggests.

Keston Williams joins the panel on stage at the Agri-Tech Summit to explain that he’s looking for new solutions now that accessing labour has become more challenging following Brexit. That’s led to three projects beginning with tenderstem broccoli in 2020, then courgettes two years ago and a herd project last year with robotic company Muddy Machines using funding from UKRI and Innovate UK.

The initial project with tenderstem broccoli started by testing image recognition, Keston says. “That’s grabbing a camera, pointing it at the crop, move it around and then develop software that can recognise it. As long as you can get around and through the leaves, it doesn’t work too badly.”

The next phase was to develop a robot, or “end-effector” as Keston calls it, that can harvest the crop. This came in two parts – first Muddy Machines developed a lightweight robot platform, called Sprout. Sprout is then fitted with bespoke tools under the canopy.

“The piece of kit we designed gently pushes the leaves out of the way, and then another arm enters the crop and picks the tenderstem broccoli,” Keston says.

“We’ve developed it as a proof of concept, but we’ve reached the project’s end point where it’s proven to be difficult and slow. At the moment, the project is parked because to scale it up and make it work is going to be extraordinarily difficult.”

Courgettes are looking more promising. “We’ve got a stage where we can recognise the courgettes, and have developed a little end effector that can pick them without damaging the main plant.

“The project is reaching its conclusion now, and it is looking more exciting to take forward to the next stage of developing an initial prototype, although I would imagine there would be multiple prototypes before it comes anywhere near being commercially viable.”

Five growers, including Barfoots, are involved in the latest “herd” project. The concept is having a harvest team of one person, who controls maybe 20 harvesting robots or rovers, which coordinate harvesting of the crop from one press of a button.

Barfoots helped Muddy Machines develop its robotic harvesting platform for crops such as courgettes which require multiple passes within a picking window. “It’s about having some sort of centralised coordination of multiple robots that logically think like a harvest manager.”

While the projects are showing the challenges of automating harvesting and processing of some crops, Keston believes it is also highlighting it is achievable. But lack of investment is slowing down progress.

“As an industry, it’s being done on a shoestring. It’s not like you have a backing of a Tesla or some huge industrial process that’s shoving millions at it to get it right. These are literally garages of clever guys making stuff, and because of that I think it will take time to get there.

“But it doesn’t have to. The proof of concept shows it is possible, it’s just the development and the engineering around it that needs to accelerate quickly and that funding needs to come from somewhere.”

Unfortunately, he says the profit margins within fresh produce aren’t enough for businesses like Barfoots to fund that development, while there isn’t enough volume in the number of robots required for a machinery business to get excited.

“As a consequence it’s languishing in a horrible midfield area that doesn’t go anywhere. I don’t have the answer of how that can change unless a philanthropic entrepreneur wants to give it a go,” he concludes.

- The World Agri-Tech Innovation Summit took place in London on September 26 and 27, 2023.

Asparagus harvesting tool showing promise

An asparagus harvesting tool to fit onto Muddy Machines robotic platform, Sprout, is showing potential to be the viable application that unlocks further development uses, says Chris Chavasse, founder and chief technological officer of Muddy Machines.

Muddy Machines developed Sprout as a fully electric platform, with a 16 KwH battery that can run for 12-16 hours depending on the tool inside its payload. It’s a 1.8m wide x 1.8m long 350kg platform without a tool – four easily accessible crop storage baskets hang off the back with the tools fitting under the canopy.

“It’s four-wheel drive, rear-wheel steering, and has a pivoting front axle to maintain contact with the ground,” Chris says. “It drives up to 1 metre/second so relatively slow – that’s about 5km/h, but it’s much slower than that as it has to stop and start to identify where the crop is.”

It’s currently slower than a person picking asparagus, which is the first tool that was developed to fit onto sprout. “We’ve been developing it for the past three seasons. It uses 3D cameras to identify where the crop is, machine learning to identify when we want to harvest, what’s right, what’s not and avoid all the crop that is immature and only harvest when it is right.”

Muddy Machines hopes to offer Sprout as a platform to other innovators or companies on which to develop their own tools, Chris says. “We are proving the platform is a viable solution, so we hope it gives confidence for others to use to develop their own tools so they can get those solutions to growers faster.

Chris Chavasse talks through the attributes of the Muddy Machines robotic platform Sprout to delegates at the Agri-Tech Summit. “When we started there wasn’t any suitable platform so we had to develop our own. It’s been hard so we don’t want others to have to go through that pain and slow them down.”

The machines have been developed so one person can supervise five to 10 robots, and because they are modular with capability of carrying different tools it allows maximum utilisation without large capital investments for growers.

Muddy Machines currently offers the robots on a harvest-as-a-service model, where it operates the robots and gets paid in the same way as a human worker would be, but it wants to transition to a hardware-as-a-service leasing model in future, Chris says.

“Growers would say they need the equivalent of 50 or 100 workers, we would calculate and provide the equivalent number of robots. The grower would pay us the equivalent they would pay for the workers.”

Three-Terry tech

Why have four wheels when three offer more flexibility and stability? The 250kg E-Terry from Germany can adapt to range of widths, can be set to different heights to suit crop growth stage and easily folds for transport and storage, says COO and co-founder Fabian Rösler.

Electrically driven and primarily for weed-scouting, it has a forward speed of 1.5km/h and covers 3ha on a full battery charge in eight hours. Pilot trials on five farms in Germany are set to start in the spring.

Rootwave goodbye to weeds

The first 15 commercial Rootwave machines are being delivered to vineyards and orchards over the next few months, says CEO Andrew Diprose.

Available as a 1.8m trailed machine for vineyards or 4m for orchards, a PTO-powered generator packs 10kW of power down to each of six 0.5m-wide electrodes. With a forward speed of 5km/h, the 18kHz high-frequency voltage fries any weeds they come into contact with.

Claimed to be as effective as glyphosate, two-thirds of prospective customers are conventional growers looking to move away from herbicides.

-

Industry-leading Research in Robotics and Automation

Based in the Lincolnshire countryside, a 10-minute drive out of the city, the Lincoln Institute for Agri-food Technology (LIAT) at the University of Lincoln, is an internationally renowned centre for industry-leading research in robotics and automation.

At its Riseholme Campus, LIAT is also home to a working farm with specialist research facilities and sector-leading expertise.

The mission of LIAT is to support and enhance the future of food and agriculture productivity, efficiency, and sustainability through research, education, and technology.

It has been a very busy year for the team, having been involved in many key Agri-tech projects.

In February, LIAT’s Reverse Coal Programme was mentioned as a positive case study in the UK Government’s Environmental Improvement Plan 2023 and highlighted as an example of how peatlands can be more responsibly managed.

The scheme is taking place at the Lapwing Estate, a 5,000-acre estate near Doncaster known for being an innovative leader in ‘rethinking peatlands’.

Peatlands are one of the most fertile lands in the UK for food growth, but the process emits excessive CO2. The alternative is Reverse Coal, which shifts to indoor farming using a sustainable biomass fuel source as its power.

The energy comes from growing biomass feed stock, which is then subjected to a thermochemical treatment (pyrolysis) to create a source of energy. The pyrolysis will also produce biochar which will then be stored in a unique storage facility demonstrating that CO2 can be permanently captured.

Reverse Coal Dr Amir Badiee is the Project Lead on behalf of the University of Lincoln.

He said: “Fossil fuels have been used for so long in food production that their negative impact cannot be understated, but this project proves that there is a better way.

“Reverse Coal sequesters carbon and produces food with positive environmental impact. This solves the inherent dilemma of bioenergy crops: the loss of land from food production.”

March saw the launch of Agri-OpenCore, an innovation to deliver an accelerated programme of robotic crop harvesting for horticulture.

Agri-OpenCore, funded by the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs’ Farming Innovation Programme, has been introduced to tackle the lack of seasonal harvest labour in the UK horticulture industry. Many crops have gone unpicked this year, leading to large amounts of unnecessary waste.

LIAT at the University of Lincoln is partner in Agri-OpenCore alongside project lead APS Salads with Dogtooth Technologies Ltd, Wootzano Ltd and Xihelm Ltd.

There is currently no robotic system that can match the speed of human picking. Agri-OpenCore aims to make progress in this area by cutting the time and cost of developing a robotic harvesting system that achieves parity with human picking.

To deliver this, Agri-OpenCore will develop the world’s first open development platform for agri-robotic harvesting, with an aim to develop commercial robotic systems for tomato and strawberry harvesting that achieve human-picking-cost-parity in two years.

Also in March, LIAT became a key partner in a new project that will improve farm sustainability and profitability by using nitrogen more effectively.

From Nitrogen Use Efficiency to Farm Profitability (NUE-Profits), funded by DEFRA’s Farming Future R&D Fund: Climate Smart Farming, will aim to make the use of nitrogen as efficient as possible for farms by using data taken throughout a season.

The project will provide farmers with a management system called ‘Framework for Improving Nitrogen’ (FINE) that uses plants as sensors.

As nitrogen use and emissions are reduced, the partnership will explore new income opportunities for farmers financed by reduced carbon emissions. The aim is to make nitrogen use measurements the new benchmark for farmers to utilise nitrogen effectively to provide more profit whilst improving sustainability in farming.

The NUE-Profits project is a partnership of AgAnalyst, the University of Lincoln, Velcourt, Dales Land Net, Dyson Farming, Agreed Earth, Assimila, European Food and Farming Partnerships, N Blacker & Sons, Hill Court Farm Research and Navigate Eco Solutions.

In May, the UK Farm to Fork Summit was held at 10 Downing Street. One of the guests at the summit was Professor Simon Pearson, Director of LIAT, who was joined by 70 other attendees from around the food sector.

The Prime Minister and members of the Cabinet viewed agri-tech research displays and spoke with the exhibitors. Additional support for the food sector was announced from the Government with a focus on agri-tech, which will involve research carried out by Professor Simon Pearson and the team at LIAT.

Speaking shortly after the event, Professor Simon Pearson, Director of LIAT, said:

“The Farm to Fork Summit was a fantastic opportunity for key players in the industry to demonstrate how important the food sector will be to the future of this country.

“Rishi Sunak and Cabinet Ministers took great interest in both the agri-tech and glasshouse sectors, which will involve work from LIAT and its partners, and have pledged a significant investment to accelerate growth over the coming years.”

In September it was confirmed that LIAT would be home toa new net zero glasshouse research and development facility, set to be built on the University of Lincoln’s Riseholme campus.

This new purpose-built glasshouse, funded by the Greater Lincolnshire Local Enterprise Partnership, will offer access to specialist research infrastructure and innovation support services. This will allow SMEs and other businesses in the agricultural sector to adapt or improve their products or services.

The glasshouse will be sub-divided into independently controlled compartments, facilitating the delivery of multiple projects at the same time throughout the year.

Eligible businesses will have access to research and knowledge transfer opportunities from experts at the University of Lincoln who will support businesses within the industry to adopt new technology, implement new processes and develop new products to transition into modern, technology-enabled businesses.

Most recently, in what has been a very busy and prosperous year for LIAT, an announcement was made that the Universities of Lincoln and Cambridge had been awarded a £4.9 million grant to fund the region’s drive to become a global innovation centre for agricultural technology.

The Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire (LINCAM) region is already a major UK production centre for crop-based agriculture and the associated supply chain, leading to what is recognised as a national agri-tech cluster.

At the Universities of Lincoln and Cambridge, agri-food innovation is focused on digital technologies, including robotics and artificial intelligence, to boost productivity. Now, the hope is that the Place Based Impact Acceleration Account award from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council – the main funding body for engineering and physical sciences research in the UK – will deliver a step change in activity.

Agricultural robot in a broccoli field Simon Pearson, Founding Director of LIAT, said: “The LINCAM agricultural sector supports 88,000 jobs, generates a value of £3.8 billion and farms more than 50% of the UK’s grade 1 land. However, despite this scale, there are still significant challenges and opportunities.

“Food production accounts for 24% of all UK greenhouse gas emissions, leads to significant biodiversity losses and drives challenging social issues – not least from seasonal worker influxes to rural communities. In addition, farmers are under relentless cost pressures which are eroding supply chain equity and local economies.

“These challenges are acute across the LINCAM region, but this funding award offers an opportunity to harness agri-tech to secure sustainable growth, bringing high-value and skilled jobs to the region.”

-

Flash, crackle, pop

Concentrated light technology has passed proof of concept as a form of weed control and is being developed through field trials. Tech Farmer sees the Earth Rover ‘CLAWS’ in action.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

CLAWS moves forward, a little more than 0.5m, and stops. There’s a flash from under the hood which lights up the young crop of lettuce below. This is quickly followed by dozens of tiny spots of blue light and there’s a rasping, crackling sound.

You realise that the spots of light are focused on the weed seedlings around the lettuces, and each one gives up a tiny wisp of smoke as it’s momentarily lit. Then there’s the rather satisfying smell of weeds being fried to death.

“We call it concentrated light technology – it works in much the same way as sunlight being focused by a magnifying glass,” explains Earth Rover CEO James Miller from behind a pair of red safety specs. “You can do the same job with lasers, but this is far more effective, efficient and safer.

“At a distance of more than 2m, you don’t really need the safety specs – these are a precaution because the operating regulations haven’t caught up with our technology yet. If we were using direct lasers, there’d be a risk of the light bouncing off a shiny surface and causing injury.”

James Miller Developed as the LightWeeder, it’s claimed to be the world’s first eye-safe, herbicide-free, carbon neutral, commercially viable weeding system. It uses semiconductor LEDs to generate light that is then concentrated precisely onto the meristem of a weed seedling – the most sensitive area of the plant and the point at which it emerges from the soil.

By now the CLAWS rover has finished picking out the weeds and is moving on to the next section – flash, crackle, pop. While it takes a fraction of a second for each weed to be fried, the length of time it pauses over an area of soil – about 1m² – varies, depending on the weed burden.

This machine tackles up to 60 weeds in a second with its three modules of concentrated light units. These are shrouded beneath the branded hood – the heart of the patent-pending technology – and James wasn’t about to let an inquisitive journo make a closer inspection. There’s a claimed work rate of 1.5ha in an 8hr day.

“Once commercialised and fully autonomous, one 2m-wide machine will look after about 4ha in a day, depending on weed burden, passing continually over taking out the weeds as they emerge,” continues James. “There are optional solar panels, which would keep it charged up for a full day, and the battery alone would power it for about half a day from a full charge.”

Frying the weeds is just one aspect of the job done by CLAWS, which stands for Concentrated Light Autonomous Weeding and Scouting. On the front and under the hood are eight built-in cameras that detect the exact location of the crop and weed seedlings. This results in a complete data map of the crop after planting, showing the plant’s exact location, size, and any early signs of disease.

The meristem detection technology allows the robot to identify the growing point of the weed, which is the most sensitive area of the plant, and apply the precise amount of light needed to eliminate it. The CLAWS makes use of edge AI processing and can create a 3D image of the crop bed. “You can have the rover scout for the crop, the weeds or both, and have the data available on a laptop, tablet or phone for decision making in real time” he adds.

The 3D image is needed so the blue light can then be focused on exactly the right place to fry the weed. “Range of depth is critical, and currently this is something of a limitation. If the target weed sits on a ridge of soil in the bed, that can put it out of range of this prototype,” notes James.

Weed identification is continually improving – every pass allows further training of the algorithms. The final limitation is size of weed. “It can control relatively large weeds, but the power consumption can be prohibitive. So it’s most efficient and effective when the weeds are at seedling stage with the meristem exposed.”

But it is a true kill – independent trials have found the CLAWS technology is as effective as herbicides at controlling both monocotyledon and dicotyledon weeds, and concentrated light offers an improvement over chemistry where there is an element of herbicide resistance. This makes the overall effectiveness of a single pass of the Earth Rover about 60% currently, but James sees no reason why this shouldn’t improve to close to 100% as the machine trains itself and the range of depth improves.

“So far, the team has focused on getting the clever bit right. The improvements will come from refining the simple bits,” he says.

The organic challenge

The farming brain and origin of the business concept behind Earth Rover belong to James Brown, director of Pollybell Farms. He manages the 2000ha Lapwing Estate, an all-organic mixed farming business based at Little Carr Farm near Gainsborough, Lincs.

800ha of arable include 200ha of field vegetables, bringing in broccoli, cauliflower, cabbages and leeks, with 400ha of organic wheat and 200ha of barley. These rotate around fertility-building leys that support sheep and dairy youngstock enterprises. “We’ve moved away from a farm rotation to a field rotation, where the cropping is decided by market demand and field requirement,” notes James Brown.

But it’s the soil type that probably has most to do with how the farming system has evolved. This is Fenland, lying over sand and clay, no more than 1m above or below sea level. “Organic matter is consistently above 30%. We’re farming in compost, which means the soil is incredibly fertile and has a very high weed burden.”

The decision to go organic was made in 1997. This may have seemed odd for a business that at the time had its own agchem supply arm, but you get the feeling James Brown enjoys the bigger challenges. “1000 acres of organic are a lot harder to manage than 1000 acres of conventional agriculture. There’s no get-out-of-jail-free card, and a zero yield is perfectly possible.”

Weed control on a Fenland organic farm soon became the biggest headache, although James points out that the high organic matter tends to erode efficacy of herbicides. “Once you knock out chemistry, the only option is mechanical and that has severe limitations.”

Ploughing is used as a rotational tool, usually brought in before the vegetable crop as this is where the yield suffers most from weed competition. “We also use mechanical hoes, and have used a precision-guided model, but there are two fundamental problems with these: firstly, when conditions are wet you can’t operate it, but that’s when most weeds emerge.

“We’ve also found the action of the hoe interferes with the roots of the crop. The weeds close to the crop plants are the most important ones to control as these are competing hardest. But yield and quality take a hit from the damage to the roots.

“I came to the conclusion that the best solution for weed control didn’t exist, which is why I founded Earth Rover,” says James.

The concept behind CLAWS came about through a chance meeting he had about six years ago with Luke Robinson, a scientist with an interest in AI and robotics. “It was Luke who pointed out that lasers are power-hungry and dangerous, but he had previous experience with concentrated light technology.”

James provided the initial funding – around £200,000 – to develop the proof of concept for Earth Rover. “It was the time when the Mars Rover was very much in the news, which did provide the inspiration for some of the design, as well as the name.”

In 2021, Earth Rover and Pollybell Farms teamed up with Agri EPI and NIAB in a £750,000, 18-month industrial research project, funded by Defra under its Transforming Food Production programme, delivered by Innovate UK. “This took the idea from concept to prototype. We also carried out the efficacy trials of the technology with NIAB and developed what the service would actually look like – we carried out interviews with other farmers.

The venture now has the backing of Mercia Asset management, and has developed the concept into two prototype units. There’s a team of eight, including Tomàs Pieras, Chief Technology Officer, who has developed the robotics and AI weed detection. “Earth Rover also has an R&D facility in Spain where we have been further developing CLAWS.”

The plan is to build the fleet up to a total of five units and run trials on a series of Pioneer farms in 2024. “We put a call out earlier this year, and the places are now all filled, but we’re always looking for more triallist farmers. The aim is for 2025 to be our first commercial season. So we’ll be selling the unit with a service and maintenance package,” explains James.

“The way I see it, up to this point farmers have just had two options for weed control – chemical and mechanical. We’ve now added a third – thermal.”

What is Concentrated Light Technology?

Ancient civilisations are known to have focused the power of the sun through concave reflection or refracted through glass to light fires for cooking and heating. The technology has seen considerable advances in recent years with the increase in renewable, solar power.

The essence of Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) lies in capturing and focusing sunlight to either generate electricity or to enhance the performance of solar arrays. Unlike traditional solar photovoltaic (PV) systems that convert sunlight directly into electricity, CSP focuses sunlight onto a receiver, which then converts the concentrated solar energy into heat. This heat can be used to generate electricity through a steam turbine or stored for later use in thermal energy storage systems.

The concept of focusing light to produce intense heat at a point has been used over millennia to focus solar rays, and has applications in renewable energy, medicine, cutting and engraving. A similar effect is achieved by focusing light-emitting diodes (LED) into a small focal spot. Applications include medicine, cutting and engraving. LEDs inherently emit light under defined angles of radiation, minimizing divergence losses compared to conventional lighting systems that radiate light all around. This means the light can be intensely concentrated producing very high temperatures at the focal point.

The lure of lasers

US startup Carbon Robotics, based in Seattle, has introduced its LaserWeeder implement that fits to a three-point hitch. The 6m wide unit features 30 industrial carbon dioxide lasers, more than three times the number on its original self-driving autonomous LaserWeeder. This gives it a claimed output of about 0.8ha per hour.

The trailed unit draws its power from the tractor, identifies weeds and targets them for elimination. Lasers use thermal energy to destroy the meristem of the weed without damaging nearby crops or disturbing the soil.

The Carbon Robotics LaserWeeder features 30 industrial carbon dioxide lasers and has a claimed output of about 0.8ha per hour. Carbon Robotics says growers who use the implements are seeing up to 80% savings in weed management costs, with a break-even period of 2-3 years. It can eliminate up to 5000 weeds per minute, identifying 99% of weeds. The LaserWeeder can operate on over 40 crops and create and deploy new deep-learning crop models within 24 to 48 hours.

The company raised $30M in series C funding earlier this year, and has units active across 17 US states and three Canadian provinces.

-

Agronomist in Focus – Todd Jex

GENERATIONAL POINTERS

Agrii agronomist Todd Jex gets a steer from his grandfather on how he’s putting new

tech into practice.I really enjoy talking to the older farming generation about farming systems and the challenges they faced during their careers. My 92-year-old grandfather is often particularly keen to point out that many of the ‘fashionable’ and talked about practices are far from new. A few years ago, he came along to a winter conference at which I was presenting field scale trial results and observations on a long term regen farming system. At the end I was expecting him to remind me that diverse longer rotations, maintaining green cover and livestock integration were features of his farming system more than 50 years ago. Instead, he remarked in disbelief at how technology has developed.

I’ve been working as an agronomist for twelve and a half years which, in the context of grandfathers farming career, is the blink of an eye, but the rate of change from a technological point of view has been quite staggering. Back in 2011 precision farming was still in its infancy. We debated electroconductivity scanning versus grid sampling to establish our soil type-based sampling zones.

We’d then build variable rate P, K, Mg and lime plans as appropriate. At this stage software programs were still primitive and at times both time consuming and frustrating in equal measure. Trying to extract and use accurate yield mapping data from the combine was an annual dual. As VR capability in machinery became more affordable and widespread growth in VR drilling and N applications became the norm with the results being positive and clear, especially in oilseed rape.

Working for Agrii I have access to the Contour digital platform, and the change and improvement from its predecessor is stark. Uploading yield maps is now fast and easy, regardless of manufacturer.

This web-based platform allows myself and my customers to have access quickly and easily to:

• Soil type clay/silt/sand content

• Variable rate (VR) planning and mapping

• NDVI satellite imagery

• Uploading and viewing yield maps

• Nutrient Management Planning, NVZ and compliance

• Past, current and trend change in soil test results

• BYDV Tsum calculation

• Disease modelling and forecasting

• Soil temperature and localised weather data

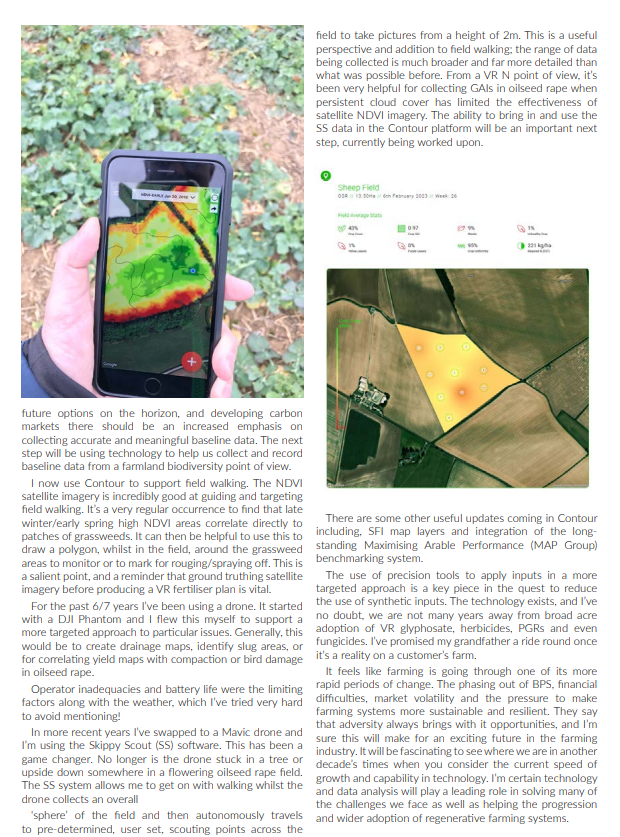

In the past six years monitoring, measuring, and managing soil health has become one of the key cornerstones of agronomy for me. Collecting accurate physical, chemical, and biological data is important but measuring how the practices we implement influence these factors is vital. I use the app to geotag soil pit and data collection points and store the information collected within the Contour platform.