If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

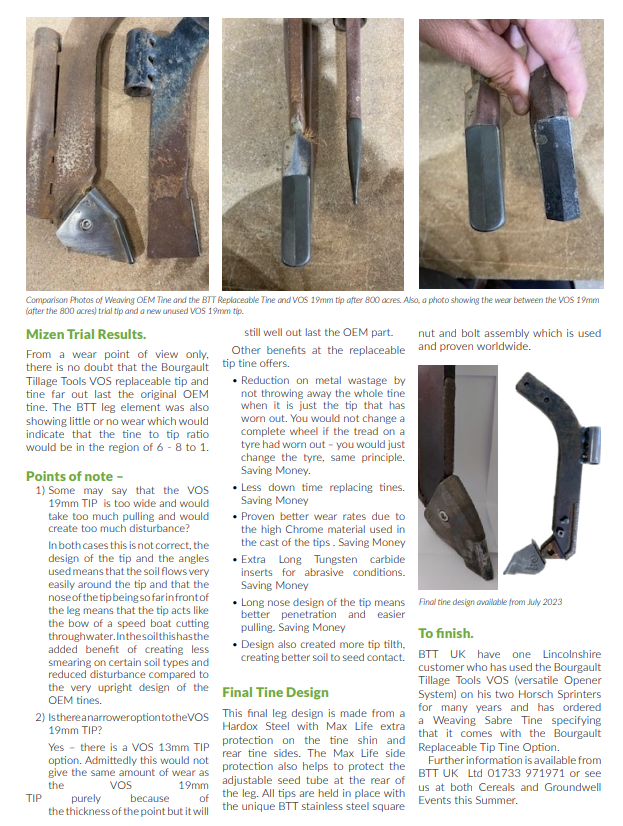

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Exploring Soil Biology’s Pivotal Role in Agriculture and Sustainability

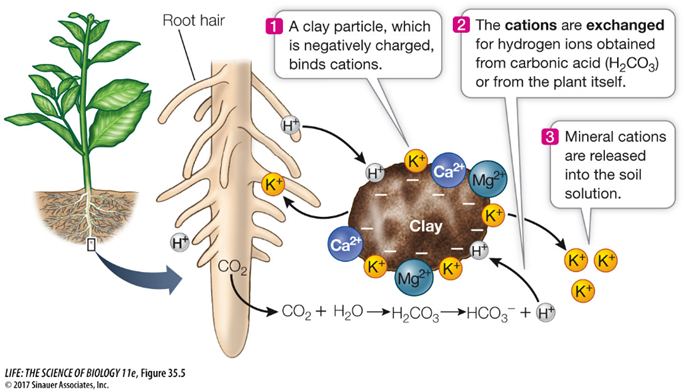

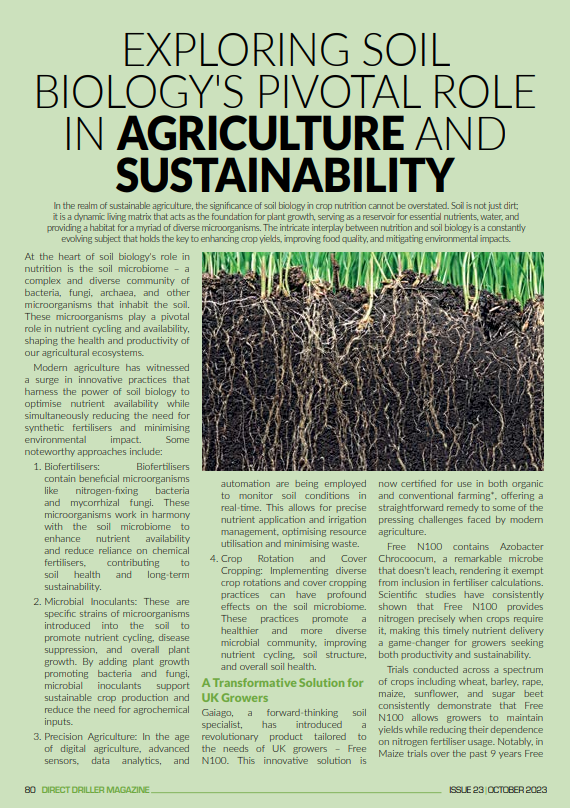

In the realm of sustainable agriculture, the significance of soil biology in crop nutrition cannot be overstated. Soil is not just dirt; it is a dynamic living matrix that acts as the foundation for plant growth, serving as a reservoir for essential nutrients, water, and providing a habitat for a myriad of diverse microorganisms. The intricate interplay between nutrition and soil biology is a constantly evolving subject that holds the key to enhancing crop yields, improving food quality, and mitigating environmental impacts.

At the heart of soil biology’s role in nutrition is the soil microbiome – a complex and diverse community of bacteria, fungi, archaea, and other microorganisms that inhabit the soil. These microorganisms play a pivotal role in nutrient cycling and availability, shaping the health and productivity of our agricultural ecosystems.

Modern agriculture has witnessed a surge in innovative practices that harness the power of soil biology to optimise nutrient availability while simultaneously reducing the need for synthetic fertilisers and minimising environmental impact. Some noteworthy approaches include:

1. Biofertilisers: Biofertilisers contain beneficial microorganisms like nitrogen-fixing bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi. These microorganisms work in harmony with the soil microbiome to enhance nutrient availability and reduce reliance on chemical fertilisers, contributing to soil health and long-term sustainability.

2. Microbial Inoculants: These are specific strains of microorganisms introduced into the soil to promote nutrient cycling, disease suppression, and overall plant growth. By adding plant growth promoting bacteria and fungi, microbial inoculants support sustainable crop production and reduce the need for agrochemical inputs.

3. Precision Agriculture: In the age of digital agriculture, advanced sensors, data analytics, and automation are being employed to monitor soil conditions in real-time. This allows for precise nutrient application and irrigation management, optimising resource utilisation and minimising waste.

4. Crop Rotation and Cover Cropping: Implementing diverse crop rotations and cover cropping practices can have profound effects on the soil microbiome. These practices promote a healthier and more diverse microbial community, improving nutrient cycling, soil structure, and overall soil health.

A Transformative Solution for UK Growers

Gaiago, a forward-thinking soil specialist, has introduced a revolutionary product tailored to the needs of UK growers – Free N100. This innovative solution is now certified for use in both organic and conventional farming*, offering a straightforward remedy to some of the pressing challenges faced by modern agriculture.

Free N100 contains Azobacter Chrocoocum, a remarkable microbe that doesn’t leach, rendering it exempt from inclusion in fertiliser calculations. Scientific studies have consistently shown that Free N100 provides nitrogen precisely when crops require it, making this timely nutrient delivery a game-changer for growers seeking both productivity and sustainability.

Gaiago’s innovative solution reflects their commitment to restoring and reinforcing the mineral and biological equilibrium of all soils while addressing three key dimensions of performance:

Agronomic Performance:

- Compensates for the limited bioavailability of alternative nitrogen sources.

- Provides self-sustaining and robust nutrition.

- Mitigates the risk of nitrogen deficiency.

- Promotes root growth, ensuring the viability of initial growth stages.

Economic Performance:

- Enhances yields across various crop categories, including field crops, specialty crops, and industrial crops.

- Safeguards protein levels, maintaining the quality of agricultural products.

- Offers the potential to reduce fertilisation while preserving yield levels, resulting in cost savings for growers.

Ecological Performance:

- Represents a natural source of non-volatile and non-leachable nitrogen, minimising environmental impact.

- Suited for sensitive and protected regions, supporting sustainable practices in ecologically fragile areas.

- Contributes to lower greenhouse gas emissions throughout the production and utilisation cycle, aligning with broader environmental sustainability goals.

In conclusion, the connection between nutrition-based soil biology and sustainable agriculture is a critical facet of modern farming practices. Understanding the intricate details between soil microorganisms and nutrient cycling processes allows us to optimise crop production while mitigating environmental impacts. As we continue to explore and uncover the complexities of soil biology, the future of agriculture holds promise in fostering healthier soils, increasing crop yields, and creating a more sustainable and resilient food system.

Gaiago’s range of products is available to purchase from Farm Deals or if you would like to speak to us in person contact, Country Manager for UK & Ireland, Mark Shaw on mark.shaw@gaiago.eu . In addition, if you are attending this year’s CropTec Show on the 29th & 30th November make sure you come and visit us on stand no 500, we look forward to seeing you there.

*Probiotic solution for use in organic farming in accordance with (EU) regulations. Gaiago’s commitment to sustainability extends to both organic and conventional farming methods.

-

Drill Manufacturer in Focus: Amazone

At Amazone, our many years, if fact over 140 years now, of experience in crop establishment means that we are able to offer the perfect solution to all cultivation techniques from no-till to scratch tillage, or even remedial deeper loosening with a range of kit that uses both discs and tines.

As we know, a farmer’s greatest asset is their soil. Soil provides the basis and infrastructure in which healthy, high-yielding crops can be grown. With the base aggregate hosting the soil water and air that we need to sustain soil life, we need a soil structure that is able to hold onto soil-borne nutrients and water and so is able to breathe, exchanging CO2 from the air and releasing oxygen as part of the growth cycle. A porous structure enables high levels of surface water to be infiltrated rather than generating run off and erosion issues and that open structure also makes for good root development thus making sure that the plant is adequately fed and watered to achieve its maximum potential. Some soils are naturally self-structuring with the natural drying and wetting process generating fissures and cracks into which the roots can get down to that moisture. Soils benefit from an increased organic content which helps feed the soil biology to promote healthy soils and a better growing environment as well as improving friability. Any increase in organic matter levels also help give the soil resilience enabling it to cope with traffic problems caused by subsequent drilling and crop care operations. Some soils, which are prone to slumping due to their fine particle sizes, might need some physical intervention to provide drainage in the form of a mechanical cultivation, but this needs to be thought through before engaging in any recreational tillage.

The increasing use of cover crops in the autumn, either as a bridge between harvest and autumn drilling, or as a means of keeping a living crop in the ground overwinter, has become an increasingly important part of the armoury in the fight against grass weeds as well as helping improve organic matter levels and boosting soil biodiversity. The ISOBUS-controlled, GreenDrill 501 catch crop seeder can be used here as part of the cultivator in order to establish those all important covers.

Generating a stale seedbed that stimulates as much regrowth of volunteers and weed seeds as possible and yet leave a weather-proof finish that can, in these days of delayed drilling dates, withstand any adverse weather that it might face in the weeks before drilling, is the ideal scenario. Running through harvest residues directly after combining with the Cobra shallow tine cultivator at 3 – 5 cm deep can ensure as much seed/soil contact as possible for those volunteers and weeds. The six rows of tines on a 16.6 cm spacing ensure sufficient surface movement – and even a full width cut when equipped with the 220 mm duckfoot share. The Crushboard behind the tines leaves a level finish for the rear roller to add some reconsolidation. Alternatively, the Catros X-Cutter, with its 480 mm wavy discs, will also move the soil surface yet at a depth of 2 – 8 cm and so also leave that safe finish. With the prevalence of cover cropping, the front knife roller, where required, crushes and bruises any green material helping to start the rotting process and opening up any shiny stalk to any contact herbicide application.

For deeper soil loosening, or as a means of incorporating surface trash with its intensive mixing effect, the Ceus disc and tine cultivator is ideal. The front-running ‘Catros’ disc element is followed by a four stagger tine element which is able to work down to depths of 30cm or so. Again, behind the tine element, runs a set of levelling discs and a double packer roller. The tines and discs can be used independently of each other thus making the Ceus a flexible soil tillage tool.

Quick and timely soil tillage is the key, so to ensure that your soils get given that perfect bill of health then make the cultivation programme as flexible as possible; dig down to see what is required, how deep are the issues and then only work as deep as necessary to alleviate those problems. Working soils less intensively will preserve soil moisture and remember, optimising organic matter incorporation starts with the combine harvester.

-

Farmer Focus: Ben Martin

Septmeber 2023

Direct Driller Sept 2023

Its hot, very hot! The last few days here on the Cambs / Suffolk boarder have been blazed in 30+ degree days, summer has arrived at last and I have been able to enjoy it safe in the knowledge that harvest is done and dusted for another year.

Writing this today, sat in a lovely little coffee shop, is a perfect excuse for me to reflect over the past 8 months since my last DD article. A lot has happened, in our personal and professional lives. My previous article was really well received, thank you to everyone who reached out to me – the power of written words never fails to amaze me!

Turning 40yrs old, moving house (during harvest!!) and my little girls 3rd birthday were all big milestones for me and my family. Moving house was particularly testing and mentally emotional, we have been so lucky to find a beautiful new home where our new landlord is a conservation farmer. There are wonderful flower margins going down our drive and we have fields at our gateway that are a wonderful array of cover crops right now and will be Wildfarmed crops next spring 😊 Just perfect!

I have really thrown myself into farm meetings, events and field walks over the past 6 months. Socially it was just what I needed, to reconnect with many old faces and to establish new relationships with some fascinating people and businesses. Some highlights included –

A visit, on a cold Feb morning, to John Pawsey’s wonderful Shimpling Park Farm was a fantastic way of starting the farm visits for 2023. Every time I get the opportunity to visit John’s business, I come away fully inspired by what is going on there. John has a wicked sense of humour; I love the way he pokes fun at himself (and others) and is always so honest about his successes and failures. I thought it was interesting how John took time to talk about his team and what he has done, and continues to do, to get that team established and to flourish.

In May I was lucky to be able to visit Andy Cato’s WildFarmed HQ at Colleymore farm, with a fantastic group from BASE UK. WHAT A DAY!! The sun was shining, Andy and his team were amazing hosts and the information shared was just mind-blowing. I don’t think I have ever been on a farm walk where everyone was so engaged and focused on what we saw and heard. Andy and his Wildfarmed team have created something special in my opinion and it was a privilege to be able to see his crops and hear from the WF team about all things marketing, production and consumer requirements.

Groundswell Festival wrapped things up for me before I turned my attention to 2023 harvest. What a wonderful 24hrs I had this year at this truly unique farming event. I hadn’t been for a couple of years and the obvious increase in size was a bit of an eye opener, but that didn’t seem to affect the quality of the festival experience for me. As with many things in life, I like to take any opportunity I get to learn new things, so with that in mind I sat in on a couple of fascinating lectures about direct sales and marketing, and Silvopasture. In the evening I caught up with an old friend I hadn’t seen from school (20yrs ago), it was just amazing to catch up with her over a cider in a such a unique setting. This event seems to of created a real chalk and cheese type feedback from many people, some that feel it has become too festival like….I find that really odd to be honest. For me, I think it is great that an event exists that has created this social / learning experience that enables people to really dial in on some fascinating topics during the day and then to unwind and socialise in the evening. My only regret was just camping 1 night, next year I will really make a 3 day event of it!

With my thoughts now on harvest, I had a brilliant opportunity to help a friend out over harvest on his farm. The first harvest for me since 2014, where I was properly back on machinery and not bogged down in the management element of it all. And I enjoyed it so much! Now harvest is done I am off to help another friend with the drilling season, another one of the jobs I use to really enjoy a lot and one that I am really excited to get stuck into again.

Getting back on machinery and working with some great farmers this year (from early spring to now) has really made me fall back in love with farming again to be honest. As a farm manager, the job can be extremely isolating at times – I have vowed going forward that I will only be surrounding myself with positive people, inside and outside of the industry. We all know that feeling of being around people that are of similar mindset to you, or at least where you want to be, you feel inspired and more motivated to get more out of life. This is why I have turned my full focus on establishing myself as a strategic farm manager, a coach and mentor. I want to help more people and businesses, utilising my farm management experiences and knowledge in lots of useful ways that I know can be really helpful.

Really focusing on myself over the past 10 months has been life changing to be honest. I have had the opportunity to be more present with my little girl and wife, which has given me a new perspective on things. I have never walked so much either, my daily dog walks are now integral in my morning routine. Getting a health and fitness coach (https://www.fatherfitpt.com) to help me reach new highs has been the best investment I have ever made, and I am about to invest in myself again with a business coach to help me really get things moving forward on that front too.

I appreciate harvest was hardwork for the majority this season, but I hope it was a safe one and one that can now be reflected on with a level of satisfaction. I wish everyone well for the upcoming drilling season and hope to see many of you at various events this autumn and winter.

Take care.

Ben

twitter https://twitter.com/bencm305

My newsletter https://greenacres.beehiiv.com/

Sunset at Groundswell 2023

Andy Cato giving us a fascinating talk at Colleymore Farm.

John Pawsey talking about his unique System Cameleon drill

-

My Nuffield Journey

Written by Ranald Angus

Ranald Angus NSch 2021

Before my Nuffield Farming Scholarship journey, I was fortunate enough to be given the chance to visit Argentina in 2014 on a Young Farmer’s study tour as part of a group of 15 enthusiastic young Scots. We gained a unique insight into an agricultural colossus on a “once in a lifetime” trip, which was a thoroughly enjoyable and unforgettable experience.

This trip was also the first time I was able to see a proper no-till system in action. I was completely blown away by the simplicity of the system. Growing two crops a year that were direct drilled into the previous crop stubble with a drill that was capable of drilling ten, twenty or thirty-inch spacings, so cereals, soya and maize could all be planted with the one machine. The driver for this was the need to reduce tillage due to its detrimental effect on the fertile Argentine soils caused by erosion when farming in a tropical and sub-tropical South American climate.

The ageing and primitive articulated tractor pulling its Argentinian-built six-meter drill was not only sowing seeds in the Argentine Pampas. It also sowed a seed in my mind about the future for crop establishment some seven and a half thousand miles away back home in the far north of Scotland.

My fascination for improving crop production was also fuelled by a nine-month working holiday to New Zealand. Throughout my time working with agricultural contractors there, I gained exposure to all manners of different crop establishment techniques. This included crops such as maize, which I had no experience working with as the northern latitude that I hail from doesn’t favour crops that need such warmth and sunlight.

I had followed the journey of people such as Tom Sewell NSch and Jake Freestone NSch, who had documented their progression to no-till in various magazine articles on the back of their Nuffield Farming Scholarships. I was also among the first subscribers to Direct Driller and still have a copy of Issue 1 in my possession, albeit in a location that has escaped my memory! However, some 12 years after my trip to New Zealand and nine years after going to Argentina, I still find myself looking for yet further understanding as we remain steadfast in our reliance on a plough and power harrow-based system for crop establishment.

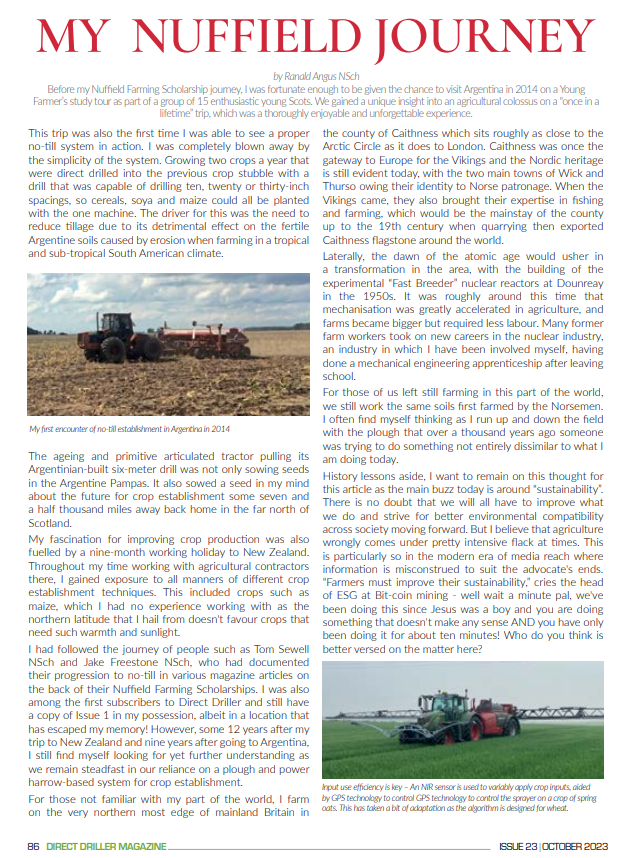

Input use efficiency is key – An NIR sensor is used to variably apply crop inputs, aided by GPS technology to control GPS technology to control the sprayer on a crop of spring oats. This has taken a bit of adaptation as the algorithm is designed for wheat. For those not familiar with my part of the world, I farm on the very northern most edge of mainland Britain in the county of Caithness which sits roughly as close to the Arctic Circle as it does to London. Caithness was once the gateway to Europe for the Vikings and the Nordic heritage is still evident today, with the two main towns of Wick and Thurso owing their identity to Norse patronage. When the Vikings came, they also brought their expertise in fishing and farming, which would be the mainstay of the county up to the 19th century when quarrying then exported Caithness flagstone around the world.

Laterally, the dawn of the atomic age would usher in a transformation in the area, with the building of the experimental “Fast Breeder” nuclear reactors at Dounreay in the 1950s. It was roughly around this time that mechanisation was greatly accelerated in agriculture, and farms became bigger but required less labour. Many former farm workers took on new careers in the nuclear industry, an industry in which I have been involved myself, having done a mechanical engineering apprenticeship after leaving school.

For those of us left still farming in this part of the world, we still work the same soils first farmed by the Norsemen. I often find myself thinking as I run up and down the field with the plough that over a thousand years ago someone was trying to do something not entirely dissimilar to what I am doing today.

History lessons aside, I want to remain on this thought for this article as the main buzz today is around “sustainability”. There is no doubt that we will all have to improve what we do and strive for better environmental compatibility across society moving forward. But I believe that agriculture wrongly comes under pretty intensive flack at times. This is particularly so in the modern era of media reach where information is misconstrued to suit the advocate’s ends. “Farmers must improve their sustainability,” cries the head of ESG at Bit-coin mining – well wait a minute pal, we’ve been doing this since Jesus was a boy and you are doing something that doesn’t make any sense AND you have only been doing it for about ten minutes! Who do you think is better versed on the matter here?

The topics of sustainability and regenerative agriculture go hand in hand, after all, why would you want to sustain or maintain when you can improve? By the letter of the law in its true definition I am not a “regenerative” farmer as I pass through the fields with the plough which goes against the principles of “movement”. However, I would like to make the case that farming practices that leave the land in a measurably improved state over time must surely be the most straightforward and simple definition of what could be regarded as regenerative.

In our area, livestock farming is the prevalent form of farming, albeit with many mixed farms producing grain either for livestock feed or selling a surplus for milling or malting. However, this last decade has seen a movement away from livestock towards more arable production. Spring cropping of barley and oats has been the main practice with most of the harvest taking place in September, with the straw being baled and cleared off the fields for livestock housing in the winter months.

This far north the growing season is short, with the cool, damp maritime climate meaning moisture removal is a greater problem than moisture retention. The need to remove straw and apply muck to stubbles and the addition of some years of harvesting in very wet conditions, mean ploughing is the favoured practice. Aeration and inversion of the soil are critically important for increasing soil temperature and removing excessive soil moisture for spring drilling.

The power of modern diggers allows us to get to the source of the water, which was not accessible to our forebearers. The advent of the Kverneland auto-reset leaf spring was a transformative technology in the north of Scotland as this was the first machine that could handle the stones. The Norwegian-born plough brought yet more Viking influence to our land! The heat treatment of the steel is similar to that of a sword, allowing the machine to bend and flex rather than break in the stony soils. This has transformed the land and has facilitated a rapid growth in farming. In this part of the world, not only is ploughing the dominant practice, but 95% of it is done by one brand of plough.

In the 1970s extensive drainage and liming were carried out under government grants, this drained a lot of poor-quality soils and improved the production capabilities of a lot of land. However, in the modern era, many of these drains are not adequate to meet the rising flow of groundwater that accumulates with the more extreme and variable weather that we are experiencing.

Another mechanical marvel to benefit us has been the development of the modern excavator. The shear hydraulic power of modern machines can deliver a fearsome break out force to rip through the ridges of rock to bleed the groundwater away through a large bore drainage pipe. This is encased in two-inch clean gravel from the depth of the drain right to subsoil level. As a result, wet or marshy ground which was only poor grazing ground, can be transformed by modern drainage techniques and transform a field into productive arable land.

In some cases, I have seen over 200 years of drainage fail to fix a problem. Stone drains, clay tiles and 1970s plastic coil pipes have all failed to bear fruit as they all have the same problem of being unable to reach the source of the problem lying in the hard rock below. Now though, we dig right through it with the movement of our fingertips. Whilst not as snazzy as the title of being a “Regen Farmer”, performing good agricultural land husbandry by creating drainage, applying lime, using crop rotations and conserving soil health make a significant impression when done right.

You must surely have earned the right to call yourself a “Regen Farmer” when you have not merely improved the land but moreover, you’ve completely transformed it. The mixed farming system is the original circular system, with soil health and crop yields being key indicators of the impact of what you are doing. With soil carbon content up at nine percent, there may be some room for improvement, but things are certainly not horrific at the moment.

For me, the concept of “Regen Farming” is about the ideas rather than the ideology, especially as farming requires a greater degree of flexibility than most other industries. The plough will continue to remain an important tool in the toolbox, but I am not opposed to a move away from it as it is a very slow and time-consuming job. The question will be how we can achieve this in our part of the world?

To me, the success of min-till or no-till relies heavily on successful cover crop production. This poses a question: How do you grow two crops in a part of the world where the growing season and the climate make it a struggle enough just to grow one main crop?

I was very grateful to have been hosted by Michael Horsch for a Nuffield visit. The discussion – Where are we going in the future as farmers? Hopefully to a version of farming that is much better than where we are now… There has been a resurgence in winter cropping over the last few years as varieties have improved greatly and weather patterns have proven to be favourable for growing the crop. Perhaps a rotation of a spring crop followed by a winter crop followed by a cover crop could be an option. The warmer temperatures of summertime and better soil conditions would be more favourable towards some reduced tillage practice. But again, this will involve a lot of trial and error to work in our growing conditions.

The other side of the coin for “Regen Ag” comes in the form of carbon sequestration. Again, in my pursuit of knowledge, I have been following the development of this field for some time, back to the days before it was trendy or anything other than a niche idea. When I decided to pursue a Nuffield Scholarship, this was the topic that I decided I would study to discover how we can sequester, quantify, verify, and then sell this carbon.

The journey to “Net Zero” is going to be a long one and the Government has already started to renege on its commitments, notably the pushback on the ban of the sale of petrol and diesel cars from 2030 to 2035. To be honest this would have to be expected as simply throwing targets out there without any solutions as to how we achieve these goals is going to be a repeating theme as we progress. The opportunity here comes in the form of farmers being the solution to many of these problems. Be it food, fibre, energy, carbon or natural capital, the farmer will have the answers, and great gains will need to be made in time to unlock the opportunity that lies beneath our feet.

At the moment, there is a lot of emphasis on carbon sequestration, but to my mind, one area which should be the starting point is input use efficiency. The biggest source of emissions on farm comes from fuel and fertiliser. Reducing these is not always a win because if your crop yield reduces, your carbon footprint will actually increase due to your output falling. Optimising the use of inputs is an old chestnut, however whilst we always aspire to chase ‘value’ over ‘cost’, moving forward the ability to further utilise technology to help us optimise and analyse will probably see a significant uptake, particularly when input costs rise.

In time some of this technology will also help us to record and quantify our soil carbon. If we are paid to carry out regenerative practices, then this will be vital record-keeping to demonstrate that a practice has been carried out. We should also be considering the value of this data, not only to ourselves but also to third parties. Ensuring that we know how this data is being used – and who can access and use it – is important, as it could have a financial value and we could be giving away for free unknowingly.

I recently listened to a well-timed podcast just before writing this article by Andrew Dewing of Dewing Grain. Despite being a grain merchant in Norfolk which is at the complete opposite end of the country to me, I listen regularly for the market updates to get a handle on where the grain trade is at. There is often a chat about various topics or interesting people, and I am relatively familiar with Norfolk as I went there for our 2021/2022 Nuffield Contemporary Scholar Conference. Episode 253 of the Dewing Grain Podcast is worth a listen as I think it is a good discussion around regenerative farming at present.

As part of my Scholarship studies, I made my first overseas trip to Germany in the summer of last year and met many great and interesting people. The highlight of my trip was to be fortunate enough to spend a day in the company of Micheal Horsch at the Horsch company headquarters in Schwandorf.

We discussed many of the topics surrounding farming right now, and indeed some of the things I have touched on in this article including carbon, direct drilling, and input inflation as well as how the short to longer-term future for farming might look. Before the day was rounded off with a beer and a barbecue, Michael was keen to show me the information gathered from a benchmarking group of German farmers of which he is a part. There was lots and lots of data here but the key point that Michael was keen to stress was the more reliance you have on ‘digitalisation’ the lower your profit is likely to be. By secluding yourself to the office you remove yourself from the reality of what is actually happening in the field. The best farmers in this group we not only consistently the best, but they made their own judgments based on what they had seen in the field.

In this modern era, which is incredibly complicated and volatile, and now increasingly technical, there is still no substitute for boots on the ground. I had also expanded my woes over the ploughing situation with him and said to him; “Michael, what I need you to build me is a new cultivator which does the job of a plough but is not a plough!” Watch this space perhaps? Agritechinca 2023 is just around the corner…

Nearly 40 Scholars will present their findings at the 2023 Nuffield Farming ‘Super Conference’ held 14-16th November at Sandy Park in Exeter. The event also includes a pre-conference visit to nearby Wastenage Farms, and tickets are not exclusive to Nuffield Scholars – ALL are welcome and encouraged to attend. Ticketing details, and a full list of presenting Scholars can be found at the QR code or on www.nuffieldscholar.org.

-

Generating revenue from soil carbon

Agricarbon has developed a scientifically robust and cost-effective method of measuring soil carbon to produce carbon credits which meet international protocols and are of high value to buyers and farmers alike. The company is working with Regenerate Outcomes, which supports farms’ transition to regenerative agriculture through mentoring from leading regenerative farmers and by selling environmental outcomes to create additional revenue.

The benefits of increasing the amount of carbon in your soil are clear; improved soil, plant and animal health, greater productivity and resilient farm businesses to name just a few.

However, soil organic carbon (or SOC) also creates the opportunity to generate additional income via the sale of carbon credits.

Regenerate Outcomes is working with farmers across the country to sponsor a long-term regenerative farming mentoring programme, as well as verification services related to soil carbon and other verifiable environmental outcomes.

Farms which join the Regenerate Outcomes programme receive long-term, one-to-one support from Understanding Ag, a leading professional mentoring agency in regenerative farming, led by farmers Gabe Brown, Dr Allen Williams and Shane New and supported by 3LM, the UK Savory Network hub.

Farmers join a 30-year agreement with Regenerate Outcomes who work with Agricarbon to baseline and monitor soil carbon stocks every five years. Soil carbon increases are verified following the world-leading Verra Carbon Standard.

“It is essential that the carbon baselining and monitoring for these credits is of the highest integrity possible and compliant with recognised carbon market protocols, to ensure the long-term value of the credits and maximise returns for our farmers,” said Regenerate Outcomes Director Tom Dillon.

“This is why we choose to work with Agricarbon, who can carry out these soil carbon surveys while balancing quality assurance with cost efficiency.”

Agricarbon provides robust evidence for soil carbon gains, defined by requirements set out in high-standard carbon credit protocols. This focus on quality means that the income generated by Regenerate Outcomes is expected to be reliable in the long term as the credits will remain attractive to carbon buyers in the years ahead.

Core extraction “The real driver for founding Agricarbon was to unlock as much value as possible from soil carbon for farmers to fund their transition to regenerative farming,” says co-founder Annie Leeson.

“It’s a process that farmers can trust. The reason they can trust it is because carbon buyers trust it. It’s been designed explicitly to meet the required standards.”

Agricarbon has built an industrial scale robotic soil processing facility, which mechanises the testing process.

“This massively reduces the cost of processing each sample which means you can take enough samples to create reliable and statistically sound baselines and measurements of changes over time,” said Annie

“Our automation and robotics also bring greater accuracy to the analysis. Testing can be unpredictable and variable if it’s done by human beings across different laboratories. Typically, the margin of error you would expect would be about 20 per cent across most labs. Agricarbon’s margin of error is far lower.

“Our automated soil processing technology also measures bulk density for every single sample. Measuring bulk density – which allows us to calculate how much soil you have got – is vital to converting the percentage of organic carbon in that soil into an accurate measure of the total tonnage of carbon.”

Regenerate Outcomes plans to sell its first batch of verified carbon credits in 2024/25.

“We believe that regenerative agriculture is the way forward for British farmers to build resilient businesses, increase productivity and farm in a way which increases biodiversity and water quality,” said Tom.

“The integrity of Agricarbon’s testing process is essential in ensuring we can create a long-term, sustainable income for farmers alongside the many other benefits it brings.”

-

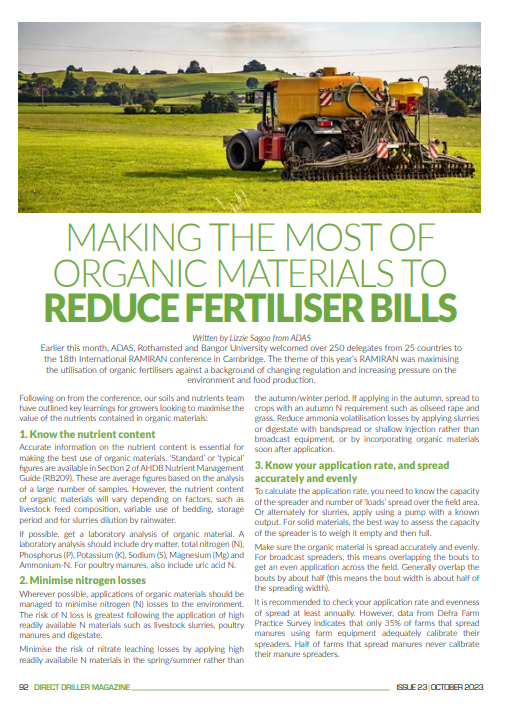

Making the most of organic materials to reduce fertiliser bills

Written by Lizzie Sagoo from ADAS

Earlier this month, ADAS, Rothamsted and Bangor University welcomed over 250 delegates from 25 countries to the 18th International RAMIRAN conference in Cambridge. The theme of this year’s RAMIRAN was maximising the utilisation of organic fertilisers against a background of changing regulation and increasing pressure on the environment and food production.

Following on from the conference, our soils and nutrients team have outlined key learnings for growers looking to maximise the value of the nutrients contained in organic materials:

1. Know the nutrient content

Accurate information on the nutrient content is essential for making the best use of organic materials. ‘Standard’ or ‘typical’ figures are available in Section 2 of AHDB Nutrient Management Guide (RB209). These are average figures based on the analysis of a large number of samples. However, the nutrient content of organic materials will vary depending on factors, such as livestock feed composition, variable use of bedding, storage period and for slurries dilution by rainwater.

If possible, get a laboratory analysis of organic material. A laboratory analysis should include dry matter, total nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), Potassium (K), Sodium (S), Magnesium (Mg) and Ammonium-N. For poultry manures, also include uric acid N.

2. Minimise nitrogen losses

Wherever possible, applications of organic materials should be managed to minimise nitrogen (N) losses to the environment. The risk of N loss is greatest following the application of high readily available N materials such as livestock slurries, poultry manures and digestate.

Minimise the risk of nitrate leaching losses by applying high readily availabile N materials in the spring/summer rather than the autumn/winter period. If applying in the autumn, spread to crops with an autumn N requirement such as oilseed rape and grass. Reduce ammonia volatilisation losses by applying slurries or digestate with bandspread or shallow injection rather than broadcast equipment, or by incorporating organic materials soon after application.

3. Know your application rate, and spread accurately and evenly

To calculate the application rate, you need to know the capacity of the spreader and number of ‘loads’ spread over the field area. Or alternately for slurries, apply using a pump with a known output. For solid materials, the best way to assess the capacity of the spreader is to weigh it empty and then full.

Make sure the organic material is spread accurately and evenly. For broadcast spreaders, this means overlapping the bouts to get an even application across the field. Generally overlap the bouts by about half (this means the bout width is about half of the spreading width).

It is recommended to check your application rate and evenness of spread at least annually. However, data from Defra Farm Practice Survey indicates that only 35% of farms that spread manures using farm equipment adequately calibrate their spreaders. Half of farms that spread manures never calibrate their manure spreaders.

4. Build your farm nutrient management plan

Management strategies that minimise environmental N losses can maximise crop N recovery and increase the fertiliser N replacement value of the manure. This reduces the need for manufactured fertiliser application to meet crop requirements. In order to realise the value of manure applications, it is important to accurately predict the crop available N supply and reduce inorganic fertiliser use accordingly.

Section 2 of the AHDB Nutrient Management Guide includes guidance on crop available N supply from organic materials. Alternatively, farmers can use the MANNER-NPK software. MANNER-NPK (MANure Nutrient Evaluation Routine) is a decision support tool to quantify manure crop available N supply and is available to download for free from www.planet4farmers.co.uk.

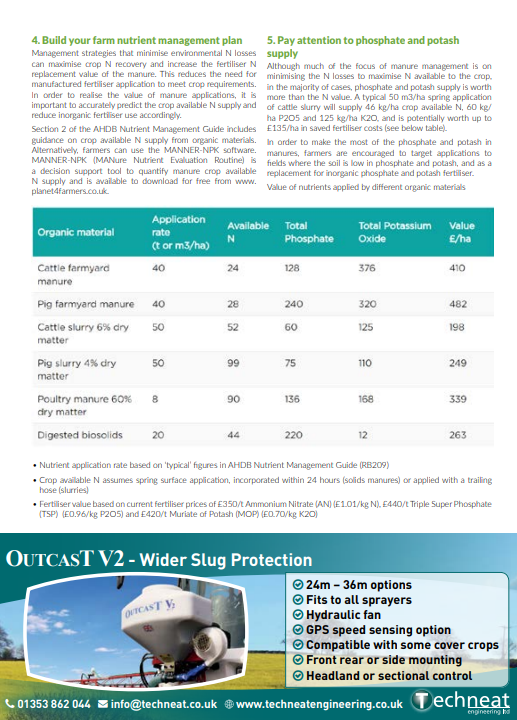

5. Pay attention to phosphate and potash supply

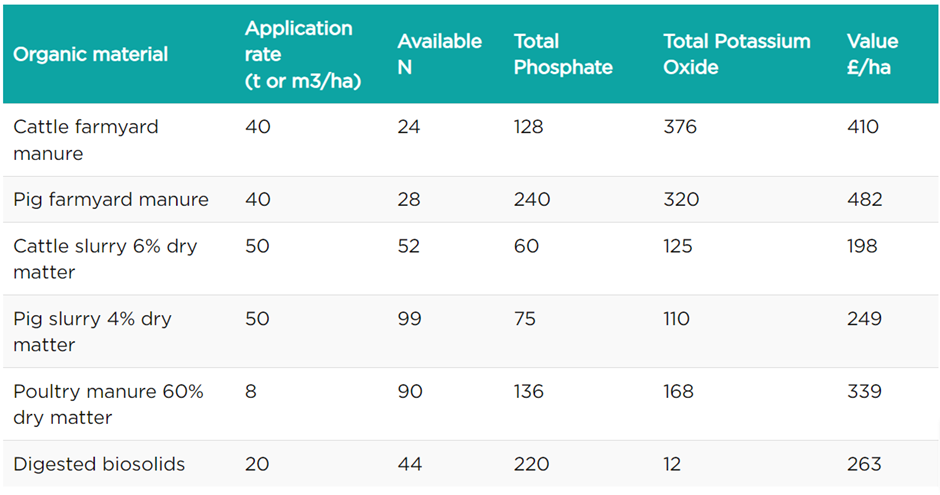

Although much of the focus of manure management is on minimising the N losses to maximise N available to the crop, in the majority of cases, phosphate and potash supply is worth more than the N value. A typical 50 m3/ha spring application of cattle slurry will supply 46 kg/ha crop available N, 60 kg/ha P2O5 and 125 kg/ha K2O, and is potentially worth up to £135/ha in saved fertiliser costs (see below table).

In order to make the most of the phosphate and potash in manures, farmers are encouraged to target applications to fields where the soil is low in phosphate and potash, and as a replacement for inorganic phosphate and potash fertiliser.

Value of nutrients applied by different organic materials

- Nutrient application rate based on ‘typical’ figures in AHDB Nutrient Management Guide (RB209)

- Crop available N assumes spring surface application, incorporated within 24 hours (solids manures) or applied with a trailing hose (slurries)

- Fertiliser value based on current fertiliser prices of £350/t Ammonium Nitrate (AN) (£1.01/kg N), £440/t Triple Super Phosphate (TSP) (£0.96/kg P2O5) and £420/t Muriate of Potash (MOP) (£0.70/kg K2O)

-

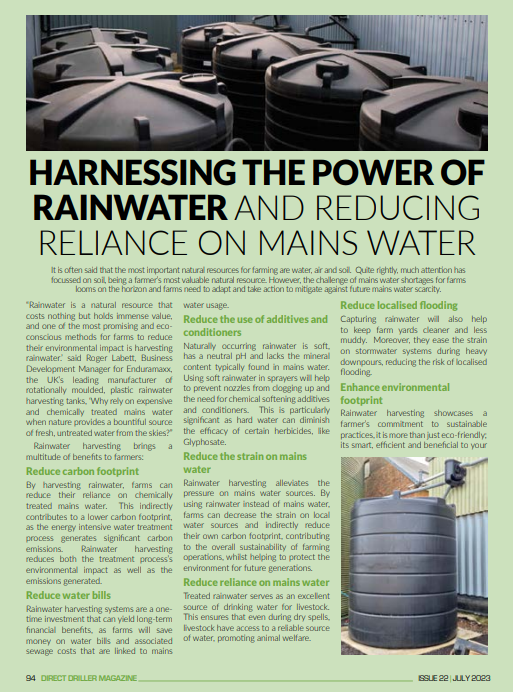

Harnessing the power of rainwater and reduce reliance mains water

Written by Helen Selkin from Enduramaxx

It is often said that the most important natural resources for farming are water, air and soil. Quite rightly, much attention has focussed on soil, being a farmer’s most valuable natural resource. However, the challenge of mains water shortages for farms looms on the horizon and farms need to adapt and take action to mitigate against future mains water scarcity.

“Rainwater is a natural resource that costs nothing but holds immense value, and one of the most promising and eco-conscious methods for farms to reduce their environmental impact is harvesting rainwater.’ said Roger Labett, Business Development Manager for Enduramaxx, the UK’s leading manufacturer of rotationally moulded, plastic rainwater harvesting tanks, ‘Why rely on expensive and chemically treated mains water when nature provides a bountiful source of fresh, untreated water from the skies?”

Rainwater harvesting brings a multitude of benefits to farmers:

Reduce carbon footprint

By harvesting rainwater, farms can reduce their reliance on chemically treated mains water. This indirectly contributes to a lower carbon footprint, as the energy intensive water treatment process generates significant carbon emissions. Rainwater harvesting reduces both the treatment process’s environmental impact as well as the emissions generated.

Reduce water bills

Rainwater harvesting systems are a one-time investment that can yield long-term financial benefits, as farms will save money on water bills and associated sewage costs that are linked to mains water usage.

Reduce the use of additives and conditioners

Naturally occurring rainwater is soft, has a neutral pH and lacks the mineral content typically found in mains water. Using soft rainwater in sprayers will help to prevent nozzles from clogging up and the need for chemical softening additives and conditioners. This is particularly significant as hard water can diminish the efficacy of certain herbicides, like Glyphosate.

Reduce the strain on mains water

Rainwater harvesting alleviates the pressure on mains water sources. By using rainwater instead of mains water, farms can decrease the strain on local water sources and indirectly reduce their own carbon footprint, contributing to the overall sustainability of farming operations, whilst helping to protect the environment for future generations.

Reduce reliance on mains water

Treated rainwater serves as an excellent source of drinking water for livestock. This ensures that even during dry spells, livestock have access to a reliable source of water, promoting animal welfare.

Reduce localised flooding

Capturing rainwater will also help to keep farm yards cleaner and less muddy. Moreover, they ease the strain on stormwater systems during heavy downpours, reducing the risk of localised flooding.

Enhance environmental footprint

Rainwater harvesting showcases a farmer’s commitment to sustainable practices, it is more than just eco-friendly; its smart, efficient and beneficial to your farm, machinery and livestock and, we expect that in the future, regulatory compliance. By visibly demonstrating a commitment to sustainability farms will enhance their reputation and marketability.

What next.

If you are keen to make a positive impact on the environment while reaping the practical benefits of rainwater harvesting you’re on the right path. Transitioning to rainwater harvesting not only benefits your farm but also contributes to a more sustainable and resilient agricultural sector.

Enduramaxx offers a range of tanks in various shapes and sizes to suit your farm’s specific needs. To learn more about how rainwater harvesting can benefit your farm, please contact Enduramaxx directly 01778 309847 or get in touch with your farm buying group or agricultural dealer. Alternatively, Enduramaxx can connect you with an approved installer in your area.

How big a rainwater harvesting tank do I need?

To determine the appropriate system for your requirements, Enduramaxx have a handy tank size calculator on their website (use QR code attached) (https://enduramaxx.co.uk/rainwater-calculator-water-catchment-calculator/) Alternatively,

Roof area (footprint) m2 x annual rainfall in m3.

Assume annual rainfall is 0.65m3 (650ml) and shed roof catchment area is 450m2 (e.g.15m x 30m)

450m2 x 650ml = 292.5 (m3), divided by 12 = 24.375 or 24,375 litres per month average.

Enduramaxx recommend storing an average of two to three months’ worth of rainfall (bear in mind you may get three months’ worth in your wettest month) and so, in the above example would recommend 3 x 25,000L tanks linked together in series.

-

Unearthing Insights: Navigating Compaction Challenges in the Transition to Conservation Agriculture

Written by Joe Stanley from the Allerton Project

It’s well established, including by our own research (in part discussed in June’s article on our pioneering Conservation Agriculture trial), that a move to reduced tillage or direct drilling (DD) can generally be considered beneficial for the triumvirate of farm economics, soil health and environmental sustainability. With financial margins inexorable tightening, increasing recognition of the degradation visited on our farm’s most vital asset in recent decades, and increased public and political demands for natural capital recovery in the farmed landscape, reduced tillage and DD tick many boxes.

However, experiences abound of overly-rapid transitions to such systems which have met with initial setbacks, with farms simply shopping in existing equipment and making the transition from intensive tillage in a single season. Sometimes in combination with a poor planting season, this has often led to very poor establishment and soil conditions with a resultant sapping of enthusiasm – or even wholesale reversion to the previous system.

Here at the Allerton Project, we sit atop pretty consistent heavy Hanslope-Denchworth series silty clay loams. Although in some ways it’s been great to adopt a conservation agriculture system over the previous twenty or so years (with drastically improved workrates and reduced fuel usage from pounding clods into submission), such soils also provide their own specific challenges in a DD system, not the least of which is the risk of compaction.

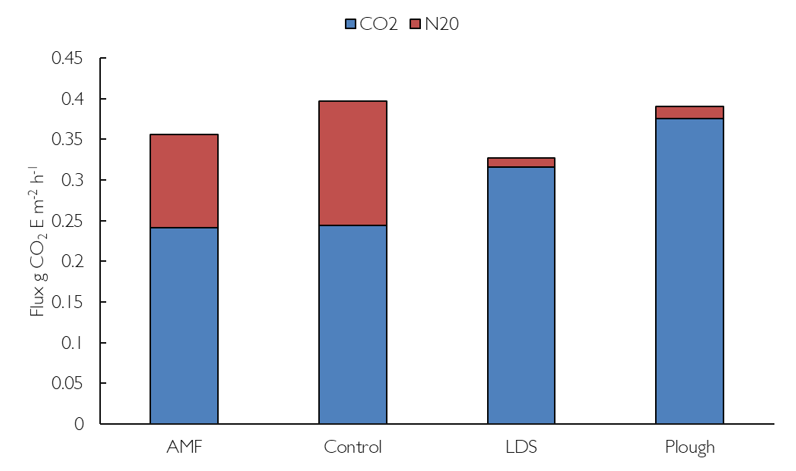

Compaction is a form of soil degradation with detrimental effects on agricultural productivity through reduced crop growth, increased soil erosion and nutrient depletion. It can also lead to increased emissions of nitrous oxide (N₂O) as anaerobically active denitrifying bacteria in damp/wet compacted soils convert available nitrate from fertiliser into this highly warming greenhouse gas, with a carbon dioxide equivalent (CO₂e) of 298. Agriculture is responsible for some 75% of UK emissions of N₂O.

In 2018 we set out to investigate the potential impact of moving to a DD system as part of SoilCare, an EU-funded project which allowed farmers in our local area to prioritise research they considered particularly useful to them; compaction in a DD system was at the top of the list.

We set up a replicated experiment with three replicates per treatment in winter barley (2018) followed by winter beans (2019). The field was intentionally compacted by driving a tractor at right angles to the tramlines (can you imagine?!) We compared direct drilling directly into the compaction with a number of compaction alleviation methods; ploughing, a pass with a low-disturbance subsoiler (LDS) and application of a mycorrhizal (AMF) inoculant, which wasn’t expected to influence soil physical characteristics but could improve crop nutrient uptake through the fungal strands. All were established with a Dale EcoDrill.

In wet winter soils we recorded N₂O emissions 10 times higher in the compacted control than in the ploughed plots, and 15 times higher than in the LDS plots. During the summer, with dry soil conditions, comparative N₂O levels flattened out between the treatments. This therefore bore out the hypothesis that compacted soils can be at significant risk of becoming a major source of emissions in the move to a DD system, despite best intentions from a soil organic matter loss/carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions point of view.

Indeed; we discovered that CO₂ losses from the two ‘disturbed’ treatments (subsoiled/ploughed) were significantly higher across the year than in the DD/AMF plots with microbes finding more available oxygen to help metabolise the soil organic matter, as would be expected. (Respiration was highest in the summer months – by around 130% – across all plots, but the significant differences in emissions were concentrated in the winter months immediately following cultivations). Indeed, CO₂ emissions from the plough plot were some 132% higher than from the control.

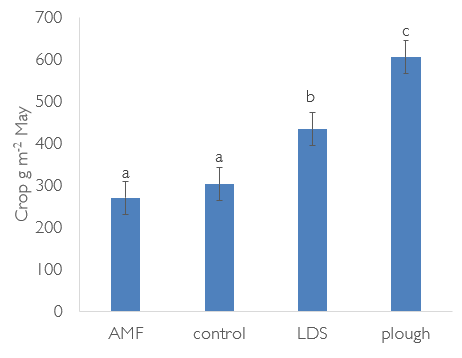

We also measured crop biomass and yield across the different treatments. In the winter barley crop in year one, biomass in the cultivated plots was significantly higher than in the DD and AMF plots (although this difference did not proceed to the bean crop in year two). Indeed, the plough biomass averaged some 600g/m² in May 2018, alongside around 400g/m² for the LDS versus around 300g/m² for both undisturbed plots. At harvest, this translated into a yield of 8.15t/ha in the ploughed plots versus 7.99t/ha for the LDS, 6.64t/ha for the AMF and 6.58t/ha for the DD. Although this seems substantial to me as a mere farmer, our research team assures me that the 1.5t/ha differential is not ‘statistically significant’, but is indicative of the difference between the treatments.

We also measured earthworm numbers and water infiltration across the field; as might be expected, earthworm numbers were significantly higher in the non-cultivated plots (and especially in the AMF plots in 2018) but water infiltration was again not ‘statistically significantly different’ across the piece – though it was higher in the cultivated areas.

As a whole, this research demonstrates that in soils liable to compaction particular care must be taken in the transition to a DD system. On emissions, when total CO₂ and N₂O outgassings were compared and adjusted for CO₂e, we discovered that the climate impact was least in the plots managed with an LDS, whilst emissions from the DD and ploughed plots were about even. However, if reduced fuel use was also taken into account in the DD plot (about 50% lower) then that would improve the picture for the non-cultivated control.

At the Allerton Project, this research has helped to inform the management of our soils. Although we direct drill as a policy, we also conduct regular monitoring of our soil health and structure and utilise our LDS where required to ameliorate compaction. This is especially important given that we do not operate a controlled-traffic system, and also operate a straw-for-muck deal in parts of the rotation which produces inevitable trafficking. Harvests such as that of 2023 also pose an issue for soil compaction, with increasingly variable and extreme weather patterns posing an increasing risk for soil travelability and health.

As part of other long-term trials on the farm, we have recorded the often-noted issues around soil structure in the transition from conventional tillage to reduced tillage and direct drilling; some of our VESS scores decline in quality in the early years, before the process of ‘self-structuring’ begins to take effect as organic matter levels and biology increase. It’s especially in this transitional period that care must be taken to avoid and alleviate compaction, through living roots if possible but mechanically if required. Indeed, we do utilise the plough within our normal rotation when agronomically justified; for us this is usually as a means of combatting blackgrass as part of a comprehensive integrated pest management strategy. Research as part of other long-term trials at Allerton has demonstrated that infrequent use of inversion tillage does not have the negative implications for soil health which might be feared.

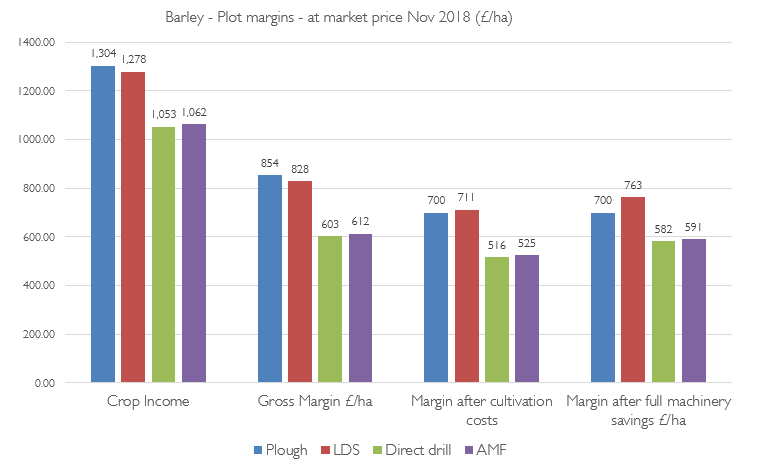

The final piece of the jigsaw with regard to our compaction experiment was to run the financial numbers on the 2018 harvest. Although income/ha was highest on the ploughed ground, when adjusted for margin after cultivation and machinery costs (assuming lower kit requirements in a DD system) the LDS plots came out on top with a margin of £763/ha versus £700/ha for the ploughed, £591/ha for the AMF and £582/ha for the DD. What we must bear in mind with these results is that the DD control was heavily compacted; in optimum conditions we would expect (and can demonstrate from other research projects) that the DD would financially outperform the plough system; this data demonstrates the importance of mechanical compaction alleviation for profitability. It would seem that the AMF treatment had limited overall impact on most metrics measured, but again needs to be viewed in the context of challenging compacted conditions.

The value of much of the research we conduct at the Allerton Project is to convert many farms’ anecdotal experience into solid data via rigorous scientific analysis, and to then make that research easily accessible and digestible for farmers on the ground. Although it might come as little surprise to learn that compaction is bad for crop production, this piece of work attaches numbers to that assumption, as well as setting it in the wider context of soil emissions. It was also curious to note that the clear results in much of year one did not necessarily translate into year two, where there was no significant difference in yield between the various treatments in the following bean crop. Our understanding of soil science is still far from complete, and this work has filled one more small gap in our understanding on the road to sustainable

-

Drill Manufacturer in Focus: Horizon

SPX Strip-Till Cultivator and PPX Planter

Will Coward is a farmer and contractor from Wiltshire, maize planting makes up around 750 acres of the contracting business alongside umbilical slurry spreading and baling being the bulk of the contracting operation.

The farming side of the business centres around a 360 head of Aberdeen Angus suckler herd.

Keen to explore the benefits of regenerative farming practices, three years ago Will took the decision to understand how strip-till cultivation could reduce ploughing and heavy cultivation to establish maize crops in line with the min-till practices they were already following on the farm.

Cover crop planting has become a bigger part of the contracting business due to catchment sensitive schemes subsidised by Wessex water locally. As Duchy of Cornwall tenant’s, they are working hard to push conservation and regenerative best practice and methods.

The challenge of growing Maize crops over the last few seasons, with wet springs was the prompt to look at different options of crop establishment.

The move from the traditional plough, subsoil and power harrow started when looking at the options for changing an ageing mounted drill.

A demo of an 8 row Horizion SPX Strip-Till cultivator quickly proved the benefits of not moving all of the soil, as the traditional methods did, fuel and time savings were instant, as much as two thirds reduced in fuel alone.

The features on the SPX Strip-Till cultivator Will particularly like were the pneumatically controlled row cleaners and consolidation, which can both be altered from the cab.

The option of being able to fit a spring tine (Vibrotine kit) in place of the Tungsten carbide wear legs was also a big selling point, the plan is to trail Strip-Till in the autumn for next year maize planting and run the Vibrotine through in the spring.

It also highlighted some of the options around drills, having tried an 8 row trailed drill on fully cultivated ground, it quickly became apparent it wasn’t completely accurate in following the strip-till cultivator.

With the Horizon SPX being a tool bar mounted, three point linkage implement, getting a trailed drill to follow accurately on curves / headlands proved more than a challenge.

The solution was all too obvious, the Horizon PPX Planter had been designed to work directly in tandem with the Horizon SPX Strip-Till Cultivator, it also offered another very distinct advantage, the option of a liquid fertiliser tank and system specifically designed to work on the drill, working in very competitive area for maize drilling, it also offered something other contractors weren’t able to.

The PPX Planter has been designed to perfectly place seed into the optimal growing environment even in the most challenging environments. High volumes of crop residue, hard no-till stubbles or uneven strip till seedbeds are just some of the challenges that the PPX can comfortably handle. The PPX won’t only perform in these challenging scenarios, it will also capture live data and make automated adjustments to ensure the optimal growing environment is achieved for every seed.

Supplied by local Dealers Redlynch Tractors, the first crop of maize was planted on the 11th of May 2023 with the new drill, Installed by Charlie Eaton from Horizon, Will was immediately impressed with how easy it was possible to control and manage the drill settings from the cab with the 20/20 screen, with accurate seed placement, both depth and spacing being paramount, the ability to be able to change the settings was something that Will saw as a benefit to the purchasing the PPX drill, even being able to see soil temperature on the screen was a real benefit to planting timings.

With its first planting season behind it, Will considers one of Horizons strongest attributes being its people. “ It was nice to know that someone was on the end of a phone on a Saturday if I was having trouble, a quick phone call answered my questions”

With crops looking better than they did last year and harvest only just around the corner, Will’s already looking at planting cover crops on land destined for maize next season, who said maize can’t be part of regen farming?

For more information on Horizion Agriculture’s products www.horizonagriculture.com

-

On-farm trials make progress towards weed seed solutions

As growers grapple for grassweed solutions, Direct Driller looks at the results from the first year of on-farm trials investigating a novel way of controlling weed seeds at harvest.

Written by Charlotte Cunningham

Grassweeds are the bane of any arable farmer’s life, with control often an uphill battle when it comes to tackling particularly persistent and resistant weeds.

Low disturbance and no-till systems are thought to be particularly vulnerable to a build-up of grassweeds as the seed shed each year stays in the germination zone, with little means of control other than repeated applications of herbicide. What’s more, there’s a heavy reliance on glyphosate, raising the prospect of resistance.

In a quest to find new solutions, a group of farmers across the country have been taking part in a new research project into a novel, chemical-free method of controlling tricky grassweeds at harvest.

The project is based around the Redekop seed control unit (SCU) technology – a retrofitted mill which sits at the back of the combine. The mill processes the chaff and is proven to kill up to 98% of weed seeds as they exit, offering growers both a way of reducing reliance on chemistry and a unique opportunity to control weeds at harvest time – something not traditionally done in the UK.

The technology has been used both extensively and successfully across North America and Australia, but the UK project is the first to put it to the test in a maritime climate.

Project background

The trials have been co-ordinated by the British On-Farm Innovation Network (BOFIN) – with test protocols developed by NIAB – on three farms across the UK.

Suffolk farmer, Adam Driver headed up the first year of trials, with an SCU fitted to his Claas Lexion 8800. Adam has a historic challenge with blackgrass building up in chaff lines of his controlled-traffic farming system and hopes the technology will be able to alleviate some of the burden. “We’re farming about 2000ha of combinable crops on a no-till system. Generally, our main weed challenge is blackgrass – we’ve got massive amounts in this area and have for a long time.”

Adam tested the technology alongside Worcestershire farmer Jake Freestone, who has an SCU fitted to his John Deere S790i in a bid to tackle meadow brome, and Warwickshire grower and Velcourt farm manager Ted Holmes, who has been trialling a unit fitted to his New Holland CR9.90 and suffers particularly with Italian ryegrass.

Year one results

Though the data set so far is small and only based on one harvest’s worth of results, there were some interesting findings from the first year’s trial, says NIAB’s Will Smith who designed its monitoring protocols and carried out the analysis on the weeds left standing at harvest.

At Adam’s farm, the headline result is that 54% of blackgrass seed was retained in winter wheat. This came as a slight surprise and was a much higher level than previously thought, admits Will.

Brome levels were also significantly reduced thanks to the use of the SCU. “I deliberately planted some winter barley in a field I know has got a lot of brome, and I haven’t found much at all,” says Adam.

While ryegrass has not typically been an issue at the farm, Adam says this is something he has seen in small amounts this year – opening up another control opportunity for the technology. “Ryegrass is something I really, really do not want here – so I’m hoping that this is something that the seed control unit will just take care of based on what we’ve seen already.”

In Warwickshire, the SCU technology enabled a 60% reduction of Italian ryegrass in winter barley and 44% in spring barley, compared with using the combine alone, which was a really positive result, says Ted.

Data was limited at Jake’s farm, though weed burdens in general were lower last year, he says.

Next steps

Building on the results of last year’s trials, Adam is leading a project that has been awarded funding from the Defra Farming Innovation Programme, delivered by Innovate UK, to continue the research under Defra’s research starter round two competition.

The three farmers from the first year of the trials will be taking part again and will be joined by Keith Challen of Belvoir Farming Company who will have the SCU unit fitted to his Fendt Ideal combine. “It has become obvious that a lot of the grassweeds we’re seeing are banded behind the combine,” says Keith. “So, to be able to control those from the combine makes a lot of sense.”

Further trials will also be taking place looking at the interaction between harvest weed seed control and cultivation strategy, led by Adam. This will involve comparing his normal no-till approach with a light cultivation to see if there is any difference in chit.

Though the effectiveness of the technology as a standalone is well-proven, the results in the field are based upon exposure to weed seed. Therefore, one of the key aims of the study going forward is to collect data on seed shed of UK-specific weed challenges – something which has been fairly limited to date, explains Will. “To use harvest weed seed control strategies, you must have seeds remaining on the heads to target. Therefore, gaining a better understanding of weed seed shed patterns is vital to proper implementation of these techniques.”

As such, the research team, co-ordinated again by BOFIN, are calling for more farmers to get involved in the project by becoming a ‘Seed Scout’. This involves collecting weed samples, assessing them via one of three simple assigned methods, and then returning the seeds to NIAB for validation. The results of this will form the UK’s first farmer-led survey of grassweeds left standing at harvest. “To accelerate the project even further, we want to collect spatially diverse data about weed seed shed across a range of weed species, in a range of crops,” notes Will.

“Therefore, we’re asking farmers to go out into the field pre-harvest or the day of harvest to collect 20 heads of the weed seed heads they’re particularly concerned with and carry out a short analysis, based on an assigned methodology. This could be counting seed heads or a visual assessment of perceived weed seed shed, for example. These samples will then be sent into us at NIAB to provide further validation and analysis. We don’t anticipate this being overly complicated or time consuming during what we know is already a busy time of year.”

Will is particularly keen that those who direct drill get involved with the project. “There’s a theory that harvest weed seed control can help no-till systems more as it reduces the risk of building up a large, shallow weed seedbank. This is where interaction with Seed Scouts will be key to tease out and explore elements of a very different approach to controlling grassweeds,” he notes.

Farmers who sign up will receive an information pack containing a guide to sampling methodology and the weed seed shedding survey to record weed status and management practices. As well as this, the pack also contains 20 small envelopes for the seed samples and a postage-paid envelope to return to NIAB. “This project and the data collection associated with it has the potential to develop some really unique and novel data which will help not only growers in the UK but also the wider industry, to ensure we’re using the right tools in the right place when it comes to tackling weed management.”

Harvest seed weed control results summary:

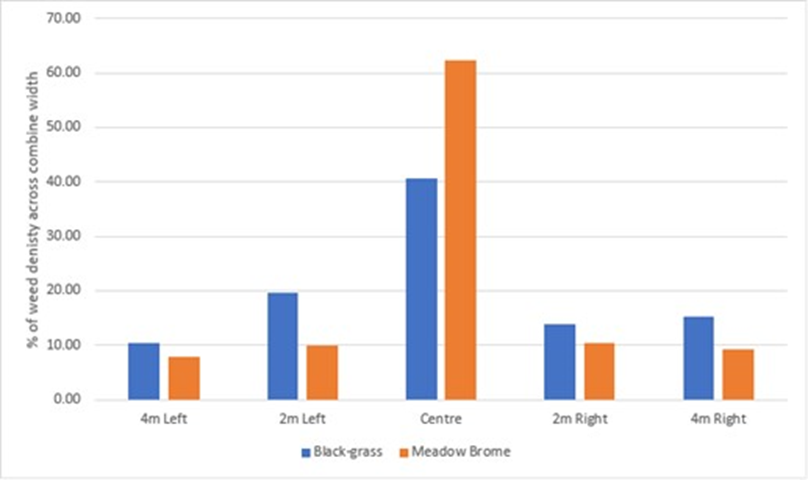

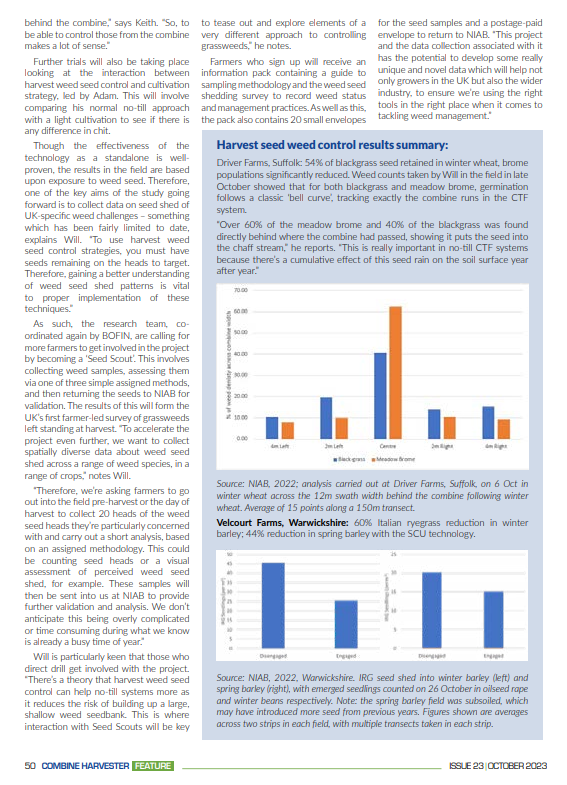

Driver Farms, Suffolk: 54% of blackgrass seed retained in winter wheat, brome populations significantly reduced. Weed counts taken by Will in the field in late October showed that for both blackgrass and meadow brome, germination follows a classic ‘bell curve’, tracking exactly the combine runs in the CTF system.

“Over 60% of the meadow brome and 40% of the blackgrass was found directly behind where the combine had passed, showing it puts the seed into the chaff stream,” he reports. “This is really important in no-till CTF systems because there’s a cumulative effect of this seed rain on the soil surface year after year.”

CAPTION: Source: NIAB, 2022; analysis carried out at Driver Farms, Suffolk, on 6 Oct in winter wheat across the 12m swath width behind the combine following winter wheat. Average of 15 points along a 150m transect.

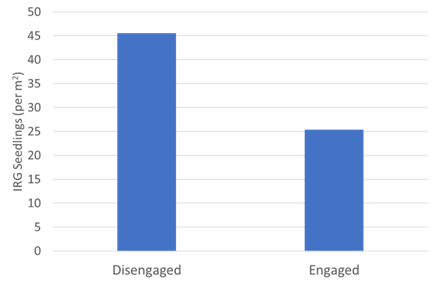

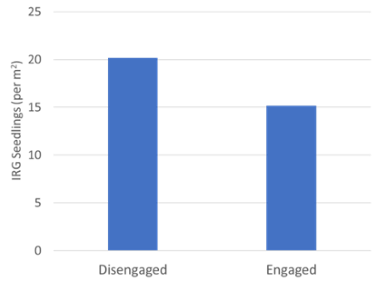

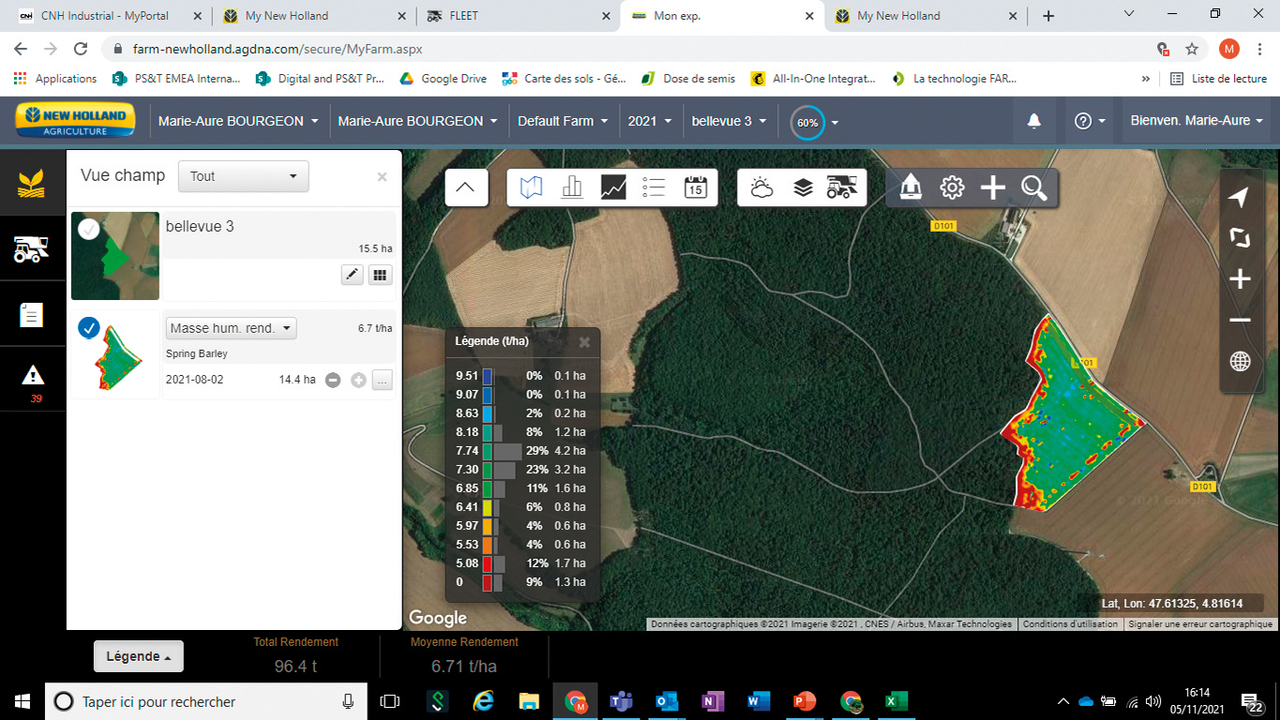

Velcourt Farms, Warwickshire: 60% Italian ryegrass reduction in winter barley; 44% reduction in spring barley with the SCU technology.

CAPTION: Source: NIAB, 2022, Warwickshire. IRG seed shed into winter barley (left) and spring barley (right), with emerged seedlings counted on 26 October in oilseed rape and winter beans respectively. Note: the spring barley field was subsoiled, which may have introduced more seed from previous years. Figures shown are averages across two strips in each field, with multiple transects taken in each strip.

-

Cleaning times reduced with innovative cooling system

As anyone that has operated a combine will know, the worst part of the job is the daily cleaning to prevent pockets of chaff building up around the engine bay and eventually getting too hot.

It’s a dusty and time-consuming job to get all the hard-to-reach areas where chaff can accumulate. However, an innovative AirSense cooling system on Fendt’s latest Ideal models has significantly reduced a large proportion of the daily cleaning required around the engine bay and exhaust system.

The AirSense system removes the need for a thorough daily clean near the engine thanks to an eight blade, 950mm reversible fan that engages based on engine temperature and time parameters. The total ventilated area is 2.7m2, and the regularity of fan engagement means that dust and chaff don’t have the chance to build up around the engine, offering extra piece of mind to operators during dusty conditions.

Ant Risdon, combine specialist at Fendt, says the AirSense system has multiple benefits for both operator and machine. “The reduced cleaning times can allow users to get cutting earlier in the day in good conditions, which is helpful in a catchy harvest. A shorter cleaning procedure each day will soon add up over a harvest period, and, for farms with large acreages to cut, could see a considerable time saving at the end.”

Inverted air flow

The system enables the fan to invert the air flow, changing it from sucking in air to cool the engine, to blowing air back through the radiators at selected times, to clear any debris build up. It also keeps the intake screen on top of the radiator free from dust and chaff build up and there is no rotary dust screen required.

It inverts by changing the pitch of the fan’s paddles. This is activated by engine temperature or time since the last inversion, and a visible plume of dust is seen rising from the engine bay when engaged. Manual activation is also possible if the operator feels it is required.

“By keeping the engine bay free of debris, combine performance is never restricted as maximum air intake through the radiator is always possible. Coupled to this, the AirSense system significantly extends the life of the air filter, which requires no cleaning during the season from the operator,” comments Ant.

The AirSense cooling system is available on all models of Fendt Ideal from the Ideal 7 with its 9.8-litre AGCO Power engine to the largest Ideal 10T, powered by a 16.2-litre six-cylinder engine offering 790hp.

Fendt has also introduced a new over pressurised exhaust box to prevent dust accumulation around the exhaust, to help reduce cleaning times and chaff build up in the hottest areas of the machine. The new AirBox is available on Ideal 8, 9 and 10 combines.

Customer viewpoint

Ben Linington – Flichity Estates

Covering 1,300ha of combinable crops in north Shropshire used to mean regular cleaning of the combine each evening for Ben Linington, estate manager at Flichity Estates. However, after changing his Case Axial Flow 9250 for a Fendt Ideal 10T for this harvest, the time saved through running the AirSense system has allowed him more options at the end of each day as the lengthy cleaning period is no longer required.

The Fendt Ideal 10T runs a 40ft Geringhof header and the AirSense cooling was one of the main attractions to changing brands, especially after the hot summer last year, as Ben describes. “During the heatwave, I was stopping to blow dust off the exhaust system every few hours to prevent any fires. It also took me an hour and a half at the end of each day to blow down the combine and engine bay ready for the next day. The AirSense system was one of the reasons I bought the Ideal, to reduce the time spent with a compressor.”

Although this is the Ideal’s first season at Flichity, the benefits to running it have been obvious as blowing down now takes 15 minutes with a leaf blower to give the combine a once over, as opposed to 90 minutes before. “It also allows me more time to check over the rest of the machine, a job that ate into the start of each day with the previous machine. The engine bay and exhaust are spotless and I have been surprised at how clean the fan keeps it.”

Along with AirSense, another reason for the Ideal purchase was grain quality. “I have never seen such a clean grain sample from a combine, and the cleaning capacity and rotors play a big role in this. Our dealer back-up from Chandlers is also very good,” concluded Ben.

-

Shredding some light on the subject

What is Near Infra-Red Spectography and how can it benefit the combine at harvest time.

Without a doubt, better information enables you to make better decisions. Information is power, you only have to look to any shopping experience where retailers will try to harvest any personal information presumably in an effort to be able to offer you an opportunity to sell you more. But within agriculture, generating information at harvest time can now provide the building blocks for the decisions that will shape the profitability of the farm for the next year and for years to come.

Yield mapping is a technology that has been around for many years now. However, if you go back fifteen years, a farm’s yield maps did little more than provide a novel wallpaper for the farm office. The key to yield mapping becoming a useful activity has been the ability to action the data generated. As farm management packages become more powerful and user-friendly, the ability to output prescriptions to enable variable fertilizer applications or variable rate seed rates have enabled farms to optimize inputs.

There are those, however, who feel that looking at yield in isolation may not give the fullest picture for example when considering fertilizer applications for following crops and a better indication might well be the quality of the crops harvested, which in turn may give a better clue of the use of nutrients – including inorganic fertilizers.

While crop quality has historically been in the bailiwick of the grain merchant, a relatively new technology has now become available to the farmer – Near Infra-Red Spectroscopy (NIR).