If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Farmer Focus – Ed Reynolds

October 2022

Harvest 2022 arrived fast and was completed without a pause. The wheats yielded 8.8t/ha, with only applied 155kg/ha bagged N applied, which was 16% less than 14yr average. 85% of this was direct drilled and we are seeing soil structure continue to improve. The oilseed rape yielded 3.3t/ha, with the highest yielding field consisting of a 3-way companion crop until January. The gross margin of this crop is hard to match with other break crops, so we have opted to roll the dice again and plant more for 2023. As I write on 20th September, the rapeseed with companion crop is experiencing much less CSFB attack, perhaps showing a benefit of diversity in a cash crop system.

This summer will be remembered on our farm for being hot and dry. We were fortunate to receive 24mm of rain on 25th August, after a period of nearly 10 weeks without rain. The dry weather threw a spanner in the works for cover crop / catch crop establishment. Indeed, we only drilled half the catch crops we intended. Because our system is linear: annual cash crop followed by cover crop sequentially, once harvest was complete, the soils were without a living root, bare and exposed to the sun. These were ‘baked out’ causing harm to the soil life that we are trying to encourage. This made me aware of the flaws in our system, where we need to look at overlapping plant cover and more living mulches.

Soil Testing

As a result of so much recent conversation around carbon in agricultural soils, with the backdrop of climate change and the opportunity to enter carbon certificate programs, we wanted to start testing our soil (Farmer Focus article – Apr 2022). The results of our original tests were quite shocking. Soil scientists look at Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) as a proportion of total clay content in the soil, so the higher the clay content, potentially the higher capacity to store stable carbon. One group of studies suggests a very good ratio for arable soil might be 1:8 carbon to clay, where as a degraded soil is 1:13 (Prout et al, 2020). The results from our first 24ha field showed a 1:16 SOC:clay content – in other words highly degraded.

This leads to the question of how it degraded to this point? To our best knowledge, this high clay content field has been in arable production since 1940’s, when American crawler tractors began to be imported as part of the increase in domestic production during WWII. It would probably have had animal manure rotationally applied until 1960’s, when livestock left this farm. Since then, it has been in arable production, using intensive cultivation and artificial fertiliser. You can see a lighter soil colour on the sloping parts of the field in the recent satellite imagery, indicating lower organic matter and implying soil erosion. I agree it is an assumption, but a safe one to say that the SOC level pre-1940 would have been significantly higher.

Given the soil test information, this leads to a bigger question – is my job as a farmer to grow crops safely and profitably for the world market, or is there a moral imperative to stop degradation of my soil, and even try to improve it? To quote from the summary of the periodical article: ‘Many arable soils in England and Wales evidently have a substantial SOC deficit, suggesting a significant opportunity to increase SOC storage to both improve soil conditions and sequester carbon’ (Prout et al, 2020). Interestingly, the field we tested is not one of our ‘worst’. It has been in no-till / very shallow till for 5 years and is functioning well under this new regime. We hope to use this and other regenerative practices to try and improve its carbon content – no danger of reaching carbon saturation point anytime soon. We have logged the sampling points and will revisit them in 10 years time.

-

Green Cover: Soil Health Resource Guide – 8TH Edition

The Purpose of This Guide

At Green Cover, our mission is to help people regenerate God’s creation for future generations. As producers who make our living from the abundant resources with which God has blessed us, we should be the most adamant and passionate conservationists. Not only do our current and future livelihoods depend on healthy functioning soils and ecosystems, but God has charged us with caring for His creation. Adam, the first farmer, was directed by his Creator to care for and protect the soil. At Green Cover, we believe that we still have this responsibility, and we are called to take the additional step of rebuilding and regenerating our soils.

We are committed to educating people about soil health and providing them with as many tools and resources as we can. This Soil Health Resource Guide is dedicated to that end. We recognize our own limited knowledge and experience, so we have invited some of the best minds in the regenerative agriculture movement to share their valuable expertise and insight for the benefit of all. To some, this guide may be a reinforcement for what they already know; to others, it may be the first step in their journey towards healthier soils. This is by no means an exhaustive soil health resource; rather, it is intended to be a concise summary of soil health concepts, and a gateway to further learning.

Think of this guide as seeds that can sprout and grow into deeper understanding if you will but plant them. We strive to have significant new content every year. While that is a good thing, it also means that many excellent articles from previous editions, some of which are catalogued at right, are not printed in this eighth edition.

Fortunately, we have allof them available on ourwebsite. We encourageyou to diversify youreducation and read thesearticles also. Let the learning continue by going to: www.greencoverseed.com/SHRG/

We invite you to do your due diligence and further explore any or all of the topics that we will touch on in this resource guide or on our website. We welcome your comments and feedback on this guide, and we are happy to provide additional copies upon request.

Keith and Brian Berns, Green Cover founders

-

What to Read – October 2022

What do you read?

If you are like us, then you don’t know where to start when it comes to other reading apart from farming magazines. However, there is so much information out there that can help us understand our businesses, farm better and understand the position of non-farmers.

We have listed a few more books you might find interesting, challenge the way you currently think and help you farm better.

The Fate of Food: What We’ll Eat in a Bigger, Hotter, Smarter World

We need to produce more food. With water and food shortages already being felt in some parts of the world, this might sound like an insurmountable challenge, but all is far from lost. You may not have heard about it, but the sustainable food revolution is already under way.

Amanda Little unveils startling innovations from the front lines around the world: farmscrapers, cloned cattle, meatless burgers, edible insects, super-bananas and microchipped cows. She meets the most creative and controversial minds changing the face of modern food production, and tackles fears over genetic modification with hard facts. The Fate of Food is a fascinating look at the threats and opportunities that lie ahead as we struggle to feed ever more people in a changing world.

Letters to a Young Farmer: On Food, Farming, and Our Future

An agricultural revolution is sweeping the land. Appreciation for high-quality food, often locally grown, an awareness of the fragility of our farmlands, and a new generation of young people interested in farming, animals, and respect for the earth have come together to create a new agrarian community. To this group of farmers, chefs, activists, and visionaries, Letters to a Young Farmer is addressed. Three dozen esteemed leaders of the changes that made this revolution possible speak to the highs and lows of farming life in vivid and personal letters specially written for this collaboration.

Barbara Kingsolver speaks to the tribe of farmers—some born to it, many self-selected—with love, admiration, and regret. Dan Barber traces the rediscovery of lost grains and foodways. Michael Pollan bridges the chasm between agriculture and nature. Bill McKibben connects the early human quest for beer to the modern challenge of farming in a rapidly changing climate.

Letters to a Young Farmer is a vital road map of how we eat and farm, and why now, more than ever before, we need farmers.

Dirt to Soil: One Family’s Journey into Regenerative Agriculture

Gabe Brown didn’t set out to change the world when he first started working alongside his father-in-law on the family farm in North Dakota. But as a series of weather-related crop disasters put Brown and his wife, Shelly, in desperate financial straits, they started making bold changes to their farm. Brown—in an effort to simply survive—began experimenting with new practices he’d learned about from reading and talking with innovative researchers and ranchers. As he and his family struggled to keep the farm viable, they found themselves on an amazing journey into a new type of farming: regenerative agriculture.

Brown dropped the use of most of the herbicides, insecticides, and synthetic fertilizers that are a standard part of conventional agriculture. He switched to no-till planting, started planting diverse cover crops mixes, and changed his grazing practices. In so doing Brown transformed a degraded farm ecosystem into one full of life—starting with the soil and working his way up, one plant and one animal at a time.

In Dirt to Soil Gabe Brown tells the story of that amazing journey and offers a wealth of innovative solutions to our most pressing and complex contemporary agricultural challenge—restoring the soil. The Brown’s Ranch model, developed over twenty years of experimentation and refinement, focuses on regenerating resources by continuously enhancing the living biology in the soil. Using regenerative agricultural principles, Brown’s Ranch has grown several inches of new topsoil in only twenty years! The 5,000-acre ranch profitably produces a wide variety of cash crops and cover crops as well as grass-finished beef and lamb, pastured laying hens, broilers, and pastured pork, all marketed directly to consumers.

The key is how we think, Brown says. In the industrial agricultural model, all thoughts are focused on killing things. But that mindset was also killing diversity, soil, and profit, Brown realized. Now he channels his creative thinking toward how he can get more life on the land—more plants, animals, and beneficial insects. “The greatest roadblock to solving a problem,” Brown says, “is the human mind.”

The Soil Will Save Us: How Scientists, Farmers, and Foodies Are Healing the Soil to Save the Planet

Journalist and bestselling author Kristin Ohlson makes an elegantly argued, passionate case for “our great green hope”—a way in which we can not only heal the land but also turn atmospheric carbon into beneficial soil carbon—and potentially reverse global warming.

Thousands of years of poor farming and ranching practices—and, especially, modern industrial agriculture—have led to the loss of up to 80 percent of carbon from the world’s soils. That carbon is now floating in the atmosphere, and even if we stopped using fossil fuels today, it would continue warming the planet.

As the granddaughter of farmers and the daughter of avid gardeners, Ohlson has long had an appreciation for the soil. A chance conversation with a local chef led her to the crossroads of science, farming, food, and environmentalism and the discovery of the only significant way to remove carbon dioxide from the air—an ecological approach that tends not only to plants and animals but also to the vast population of underground microorganisms that fix carbon in the soil. Ohlson introduces the visionaries—scientists, farmers, ranchers, and landscapers—who are figuring out in the lab and on the ground how to build healthy soil, which solves myriad problems: drought, erosion, air and water pollution, and food quality, as well as climate change. Her discoveries and vivid storytelling will revolutionize the way we think about our food, our landscapes, our plants, and our relationship to Earth.

Holy Shit: Managing Manure to Save Mankind

In his insightful new book, Holy Shit: Managing Manure to Save Mankind, contrary farmer Gene Logsdon provides the inside story of manure-our greatest, yet most misunderstood, natural resource. He begins by lamenting a modern society that not only throws away both animal and human manure-worth billions of dollars in fertilizer value-but that spends a staggering amount of money to do so. This wastefulness makes even less sense as the supply of mined or chemically synthesized fertilizers dwindles and their cost skyrockets. In fact, he argues, if we do not learn how to turn our manures into fertilizer to keep food production in line with increasing population, our civilization, like so many that went before it, will inevitably decline. With his trademark humor, his years of experience writing about both farming and waste management, and his uncanny eye for the small but important details, Logsdon artfully describes how to manage farm manure, pet manure and human manure to make fertilizer and humus. He covers the field, so to speak, discussing topics like: How to select the right pitchfork for the job and use it correctly How to operate a small manure spreader How to build a barn manure pack with farm animal manure How to compost cat and dog waste How to recycle toilet water for irrigation purposes, and How to get rid ourselves of our irrational paranoia about feces and urine. Gene Logsdon does not mince words. This fresh, fascinating and entertaining look at an earthy, but absolutely crucial subject, is a small gem and is destined to become a classic of our agricultural literature.

The Carbon Farming Solution

Agriculture is currently a major net producer of greenhouse gases, with little prospect of improvement unless things change markedly. In The Carbon Farming Solution, Eric Toensmeier puts carbon sequestration at the forefront and shows how agriculture can be a net absorber of carbon. Improved forms of annual-based agriculture can help to a degree; however to maximize carbon sequestration, it is perennial crops we must look at, whether it be perennial grains, other perennial staples, or agroforestry systems incorporating trees and other crops. In this impressive book, backed up with numerous tables and references, the author has assembled a toolkit that will be of great use to anybody involved in agriculture whether in the tropics or colder northern regions. For me the highlights are the chapters covering perennial crop species organized by use staple crops, protein crops, oil crops, industrial crops, etc. with some seven hundred species described. There are crops here for all climate types, with good information on cultivation and yields, so that wherever you are, you will be able to find suitable recommended perennial crops. This is an excellent book that gives great hope without being naïve and makes a clear reasoned argument for a more perennial-based agriculture to both feed people and take carbon out of the air. Martin Crawford, director, The Agroforestry Research Trust; author of Creating a Forest Garden and Trees for Gardens, Orchards, and Permaculture

Mycorrhizal Planet: How Symbiotic Fungi Work with Roots to Support Plant Health and Build Soil

Mycorrhizal fungi have been waiting a long time for people to recognize just how important they are to the making of dynamic soils. These microscopic organisms partner with the root systems of approximately 95 percent of the plants on Earth, and they sequester carbon in much more meaningful ways than human “carbon offsets” will ever achieve. Pick up a handful of old-growth forest soil and you are holding 26 miles of threadlike fungal mycelia, if it could be stretched it out in a straight line. Most of these soil fungi are mycorrhizal, supporting plant health in elegant and sophisticated ways. The boost to green immune function in plants and community-wide networking turns out to be the true basis of ecosystem resiliency. A profound intelligence exists in the underground nutrient exchange between fungi and plant roots, which in turn determines the nutrient density of the foods we grow and eat.

Exploring the science of symbiotic fungi in layman’s terms, holistic farmer Michael Phillips (author of The Holistic Orchard and The Apple Grower) sets the stage for practical applications across the landscape. The real impetus behind no-till farming, gardening with mulches, cover cropping, digging with broadforks, shallow cultivation, forest-edge orcharding, and everything related to permaculture is to help the plants and fungi to prosper . . . which means we prosper as well.

Building soil structure and fertility that lasts for ages results only once we comprehend the nondisturbance principle. As the author says, “What a grower understands, a grower will do.” Mycorrhizal Planet abounds with insights into “fungal consciousness” and offers practical, regenerative techniques that are pertinent to gardeners, landscapers, orchardists, foresters, and farmers. Michael’s fungal acumen will resonate with everyone who is fascinated with the unseen workings of nature and concerned about maintaining and restoring the health of our soils, our climate, and the quality of life on Earth for generations to come.

-

New Professional Register For Environmental Advisers

Managing the farmed landscape to both produce food and deliver for the environment is becoming increasingly important – from a legislation point of view, in terms of meeting government targets for biodiversity, water quality, woodland planting and net zero; from a business point of view with being able to ensure maximum environmental potential from the farm; but also for you and the local community with the joy of seeing a new species flourishing, organic matter levels increasing and your margins buzzing with pollinators.

Every farmer and land manager has a huge amount of knowledge to draw from, in order to manage and enhance the farmed landscape and achieve their own, local and national ambitions. However, do you also work with advisers to learn more, to use their expertise and experience to put together options or manage habitats and to enjoy sharing in the successes from the introduction of new practices?

Working with advisers who have technical environmental knowledge and understanding, along with an appreciation of farm business economics and how to effectively manage integration of practices with production is becoming increasingly integral across the UK. For this reason, BASIS have worked with stakeholders and organisations from across the sector to develop anew Environmental Advisers Register. This Register provides professional recognition of the role these advisers play, in working with farm businesses to achieve environmental outcomes.

The Register has been designed for the breadth of individuals delivering environmental advice with a farm business – from biodiversity, air, climate, energy and productivity knowledge, to effective management of plant health, livestock, nutrients, soil, water, woodland and the historic environment.

Advisers joining the Register will need to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of environmental land management by either completing a qualification to entry, currently the BETA Conservation Management course, or by applying for acquired rights, based on the significant experience they have gained whilst working in the industry. In addition, there will be the requirement to combine this with ongoing continuous professional development each year, which ensures all members of the Register have the up-to-date knowledge and skills to deliver advice which meets the needs of farmers and land managers.

Members of the Register will also be able to appear in a public, online directory, which farmers, land managers and advisers can use to find expertise on a particular subject in their local area – perhaps to put together a new agri-environment scheme application, carry out a surveyor create a new management plan. The aspiration of this Register is that it will create an industry standard for integrated advice delivery, raise standards across the industry and support farmers and land managers to enable sustainable productive and profitable, farming businesses, whilst delivering against national environmental ambitions.

For more information, please visit: www.basis-reg.co.uk/environmental-advisers.

-

Farmer Focus – Ed Reynolds

Harvest 2022 arrived fast and was completed without a pause. The wheats yielded 8.8t/ha, with only applied155kg/ha bagged N applied, which was 16% less than 14yraverage. 85% of this was direct drilled and we are seeing soil structure continue to improve. The oilseed rape yielded3.3t/ha, with the highest yielding field consisting of a 3-waycompanion crop until January. The gross margin of this crop is hard to match with other break crops, so we have opted to roll the dice again and plant more for 2023. As I write on 20th September, the rapeseed with companion crop is experiencing much less CSFB attack, perhaps showing a benefit of diversity in a cash crop system.

This summer will be remembered on our farm for being hot and dry. We were fortunate to receive 24mm of rain on 25thAugust, after a period of nearly 10 weeks without rain. The dry weather threw a spanner in the works for cover crop /catch crop establishment. Indeed, we only drilled half the catch crops we intended. Because our system is linear: annual cash crop followed by cover crop sequentially, once harvest was complete, the soils were without a living root, bare and exposed to the sun. These were ‘baked out’ causing harm to the soil life that we are trying to encourage. This made me aware of the flaws in our system, where we need to look at overlapping plant cover and more living mulches.

Soil Testing As a result of so much recent conversation around carbon in agricultural soils, with the backdrop of climate change and the opportunity to enter carbon certificate programs, we wanted to start testing our soil (Farmer Focus article – Apr 2022). The results of our original tests were quite shocking. Soil scientists look at Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) as a proportion of total clay content in the soil, so the higher the clay content, potentially the higher capacity to store stable carbon. One group of studies suggests a very good ratio for arable soil might be 1:8carbon to clay, where as a degraded soil is 1:13 (Prout et al,2020). The results from our first 24ha field showed a 1:16SOC:clay content – in other words highly degraded.

This leads to the question of how it degraded to this point? To our best knowledge, this high clay content field has been in arable production since 1940’s, when American crawler tractors began to be imported as part of the increase in domestic production during WWII. It would probably have had animal manure rotationally applied until 1960’s, when livestock left this farm. Since then, it has been in arable production, using intensive cultivation and artificial fertiliser. You can see a lighter soil colour on the sloping parts of the field in the recent satellite imagery, indicating lower organic matter and implying soil erosion. I agree it is an assumption, but a safe one to say that the SOC level pre-1940 would have been significantly higher.

Given the soil test information, this leads to a bigger question- is my job as a farmer to grow crops safely and profitably for the world market, or is there a moral imperative to stop degradation of my soil, and even try to improve it? To quote from the summary of the periodical article: ‘Many arable soils in England and Wales evidently have a substantial SOC deficit, suggesting a significant opportunity to increase SOC storage to both improve soil conditions and sequester carbon’ (Proutet al, 2020). Interestingly, the field we tested is not one of our ‘worst’. It has been in no-till / very shallow till for 5 years and is functioning well under this new regime. We hope to use this and other regenerative practices to try and improve its carbon content – no danger of reaching carbon saturation point anytime soon. We have logged the sampling points and will revisit them in 10 years time.

Could you explain this in more detail?

Theodor Leeb: On the high-yield sites stubble cultivation is usually carried out after the harvest to mix in the straw. After a few days or weeks volunteer crops and weeds emerge. I.e. the field more or less is green all-over. Spotting does not make sense as the plants are too close to each other. So you would have to treat the whole area and could not rely on point application. In dry regions where no-till farming is very common this is different. There is no tillage after the harvest. As it is very dry there are little weeds or catch crops. And in this case, you can – instead of spraying all over – work with a camera system in a targeted way for example to save costs when using glyphosate for spraying the individual plants.

-

Nitrogen Stabilisers(Part 1): Inhibitors

Joel Williams, Integrated Soils

Reductions in nitrogen fertiliser use and associated greenhouse gas (GHG)emissions is of course high on the agenda in recent times – you’d have to be living under a rock to have missed this memo! In many countries around the world, we are seeing legislation from governments striving to limit the release of GHGs in order to meet emissions and sustainability targets. The use of low efficiency nitrogen fertilisers is of course one of the major sources, contributing both ammonia (NH3+) and nitrous oxide (N2O). Production systems that are dependent on external N inputs are highly vulnerable to the impacts of this impetus and farmers who have been experimenting and trialling lower N strategies will be well poised to weather the upcoming changes.

There is no silver bullet to addressing the nitrogen dilemma, a multi-pronged approach that integrates many tools into the toolbox is required. One such strategy involves the use of stabilised nitrogen fertilisers – often called enhanced efficiency fertilisers – which make use of chemical inhibitors to slow N transformations in the soil and prevent losses. Urease inhibitors (UI) slow ammonia production while nitrification inhibitors (NI) slow nitrate formation(which can ultimately be converted to N2O during anaerobic conditions).These inhibitors are very targeted and they have been proven highly effective in reducing production of these twoGHGs1. However, there has been some concern raised about their potential side effects on soil biology – this is something I have been asked numerous times over the years. There are two recent studies that have investigated this question and I thought it was worth sharing their findings. The bottom line was that both studies found no effect of UI and only a mild and temporary effect of NI but let’s expand with a touch more detail…

Firstly, a short-term study2 in Canada applied urea-ammonium nitrate (UAN)with and without both urease and nitrification inhibitors and followed up monitoring the effects on the soil microbiome for 16 days. The addition of the inhibitors to UAN had only minor effects on the abundance or activity of target and non-target N-cycling microbial groups which was temporarily observed around day 9 after fertiliser application, but no longer evident by the end of the study period. Along with these minor and transient impacts, a significant ~68% reduction in N2Oemissions was achieved2.Secondly, a more recent and longer term paper3 from Ireland studied the effects of UI and NI on soil microbial communities and biological function in a grassland soil over a 5 year period.

After5 years of repeated applications, there was no impact of either inhibitor on non-target microbes while function and abundance of N cycling communities were for the most part, unaffected by fertilisation or the use of inhibitors; although, the NI did reduce the abundance of a bacteria which produceN2O. Although the inhibitors had a fairly negligible effect, this study found the fertiliser itself did have an impact on the fungal community structure but no impact on bacterial communitystructure3.

So it appears nitrogen inhibitors are not only effective at stabilising nitrogen inputs in the soil, they also have a minor effect on the soil microbiome, making them a potential valuable tool as part of an integrated nitrogen management approach. That said however, there are some reports of urease inhibitor shaving negative effects on plant growth by entering the plant and supressing the urease enzyme internally. From a plant nutrition perspective, the ureas enzyme catalyses the breakdown of urea, liberating the embedded N to be utilised by the plant to ultimately synthesise amino acids and proteins. Consequently, using a UI which can block the activity of this key enzyme internally can lead to a build up of urea and additionally prevent adequate protein synthesis (of course important for plant health and quality).

A study from as early as 1989 highlighted that plant uptake of UI increased both leaf-tip necrosis and urea concentrations to toxic levels in both wheat and sorghum4. Another study with maize demonstrated that UI can heavily interfere with urea nutrition, limiting uptake as well as the following assimilation pathway5. Lastly, a very recent study from earlier this year applied foliar urea with a UI onto pineapples– a reduction in urease activity was observed which corresponded in high levels of urea and diminished levels of ammonium, amino acids and protein in the pineapple leaves6. Combined, these studies all indicate that UI are taken up by plants, can influence N uptake and disrupt N metabolism and hence protein synthesis. That said, keep in mind that plants do make use of a range of N sources beyond just urea so utilisation of ammonium, nitrate, amino acids, proteins and bacterial endophytes can still function and support plant growth; however, the broader goal of optimising plant growth and production should aim to support all sources and pathways of N nutrition.

In part 2 of this article, we will explore the potential of some of the alternatives to chemical inhibitors, namely C-based inputs.

References:

1. Urease and Nitrification Inhibitors—As Mitigation Tools for Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Sustainable Dairy Systems: A Review. (2020). doi.org/10.3390/SU12156018

2. Short-term response of soil N-cycling genes and transcripts to fertilization with nitrification and urease inhibitors, and relationship with field-scale N2O emissions. (2020). doi.org/10.1016/J.SOILBIO.2019.107703

3. Assessing the long-term impact of urease and nitrification inhibitor use on microbial community composition, diversity and function in grassland soil. (2022). doi.org/10.1016/J.SOILBIO.2022.108709

4. Potential phytotoxicity associated with the use of soil urease inhibitors. (1989). doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.86.4.1110

5. The urease inhibitor NBPT negatively affects DUR3-mediated uptake and assimilation of urea in maize roots.(2015). doi.org/10.1073/pnas.8

6.4.11106. Transient application of foliar urea with N-(n-Butyl) thiophosphoric triamide on N metabolism of pineapple under controlled condition. (2022). doi.org/10.1016/J.SCIENTA.2021.110822

-

What Do You Read?

If you are like us, then you don’t know where to start when it comes to other reading apart from farming magazines. However, there is so much information out there that can help us understand our businesses, farm better and understand the position of non-farmers.

We have listed a few more books you might find interesting, challenge the way you currently think and help you farm better.

The Fate of Food: What We’ll Eat in a Bigger, Hotter, Smarter World

We need to produce more food. With water and food shortages already being felt in some parts of the world, this might sound like an insurmountable challenge, but all is far from lost. You may not have heard about it, but the sustainable food revolution is already under way. Amanda Little unveils startling innovations from the front lines around the world: farmscrapers, cloned cattle, meatless burgers, edible insects, super bananas and microchipped cows. She meets the most creative and controversial minds changing the face of modern food production, and tackles fears over genetic modification with hard facts. The Fate of Food is a fascinating look at the threats and opportunities that lie ahead as we struggle to feed evermore people in a changing world.

Letters to a Young Farmer: On Food, Farming, and Our Future

An agricultural revolution is sweeping the land. Appreciation for high-quality food, often locally grown, an awareness of the fragility of our farmlands, and a new generation of young people interested in farming, animals, and respect for the earth have come together to create a new agrarian community. To this group of farmers, chefs, activists, and visionaries, Letters to a Young Farmer is addressed. Three dozen esteemed leaders of the changes that made this revolution possible speak to the highs and lows of farming life in vivid and personal letters specially written for this collaboration. Barbara Kingsolver speaks to the tribe of farmers—some born to it, many self-selected—with love, admiration, and regret. Dan Barber traces the rediscovery of lost grains and food ways. Michael Pollan bridges the chasm between agriculture and nature. Bill McKibben connects the early human quest for beer to the modern challenge of farming in a rapidly changing climate. We have listed a few more books you might find interesting, challenge the way you currently think and help you farm better.

Dirt to Soil: One Family’s Journey into Regenerative Agriculture

Gabe Brown didn’t set out to change the world when he first started working alongside his father-in-law on the family farm in North Dakota. But as a series of weather-related crop disasters put Brown and his wife, Shelly, in desperate financial straits, they started making bold changes to their farm. Brown—in an effort to simply survive—began experimenting with new practices he’d learned about from reading and talking with innovative researchers and ranchers. As he and his family struggled to keep the farm viable, they found themselves on an amazing journey into a new type of farming: regenerative agriculture.

Brown dropped the use of most of the herbicides, insecticides, and synthetic fertilizers that are a standard part of conventional agriculture. He switched to no-till planting, started planting diverse cover crops mixes, and changed his grazing practices. In so doing Brown transformed a degraded farm ecosystem into one full of life—starting with the soil and working his way up, one plant and one animal at a time. In Dirt to Soil Gabe Brown tells the story of that amazing journey and offers a wealth of innovative solutions to our most pressing and complex contemporary agricultural challenge—restoring the soil. The Brown’s Ranch model, developed over twenty years of experimentation and refinement, focuses on regenerating resources by continuously enhancing the living biology in the soil.

Using regenerative agricultural principles, Brown’s Ranch has grown several inches of new top soil in only twenty years! The 5,000-acreranch profitably produces a wide variety of cash crops and cover crops as well as grass-finished beef and lamb, pastured laying hens, broilers, and pastured pork, all marketed directly to consumers. The key is how we think, Brown says. In the industrial agricultural model, all thoughts are focused on killing things. But that mindset was also killing diversity, soil, and profit, Brown realized. Now he channels his creative thinking toward how he can get more life on the land—more plants, animals, and beneficial insects. “The greatest roadblock to solving a problem,” Brown says, “is the human mind.”

The Soil Will Save Us: How Scientists, Farmers, and Foodies Are Healing the Soil to Save the Planet

Journalist and bestselling author Kristin Ohlson makes an elegantly argued, passionate case for “our great green hope”—a way in which we cannot only heal the land but also turn atmospheric carbon into beneficial soil carbon—and potentially reverse global warming. Thousands of years of poor farming and ranching practices—and, especially, modern industrial agriculture—have led to the loss of up to 80 percent of carbon from the world’s soils. That carbon is now floating in the atmosphere, and even if we stopped using fossil fuels today, it would continue warming the planet. As the granddaughter of farmers and the daughter of avid gardeners, Ohlson has long had an appreciation for the soil.

A chance conversation with a local chef led her to the crossroads of science, farming, food, and environmentalism and the discovery of the only significant way to remove carbon dioxide from the air—an ecological approach that tends not only to plants and animals but also to the vast population of underground microorganisms that fix carbon in the soil. Ohlson introduces the visionaries—scientists, farmers, ranchers, and landscapers—who are figuring out in the lab and on the ground how to build healthy soil, which solves myriad problems: drought, erosion, air and water pollution, and food quality, as well as climate change. Her discoveries and vivid storytelling will revolutionize the way we think about our food, our landscapes, our plants, and our relationship to Earth.

Holy Shit: Managing Manure to Save Mankind

In his insightful new book, Holy Shit: Managing Manure to Save Mankind, contrary farmer Gene Logsdon provides the inside story of manure – our greatest, yet most misunderstood, natural resource. He begins by lamenting a modern society that not only throws away both animal and human manure – worth billions of dollars in fertilizer value – but that spends a staggering amount of money to do so. This wastefulness make seven less sense as the supply of minedor chemically synthesized fertilizers dwindles and their cost skyrockets. In fact, he argues, if we do not learn how to turn our manures into fertilizer to keep food production in line within creasing population, our civilization, like so many that went before it, will inevitably decline. With his trade mark humour, his years of experience writing about both farming and waste management, and his uncanny eye for the small but important details, Logsdon artfully describes how to manage farm manure, pet manure and human manure to make fertiliser and humus. He covers the field, so to speak, discussing topics like: How to select the right pitch fork for the job and use it correctly How to operate a small manure spreader How to build a barn manure pack with farm animal manure How to compost cat and dog waste How to recycle toilet water for irrigation purposes, and How to get rid ourselves of our irrational paranoia about faeces and urine. Gene Logsdon does not mince words. This fresh, fascinating and entertaining look at an earthy, but absolutely crucial subject, is a small gem and is destined to become a classic of our agricultural literature.

-

Direct Driller Patrons

Thank you to those who has signed up to be a Direct Driller Patron after the last issue. Our farmer writers are now rewarded for sharing their hard-earned knowledge and our readers have the facility to place a value upon that. The Direct Driller Patron programme gives readers the opportunity to “pay it forward” and place a value on what they get from the magazine. But only once they feel they have learned something valuable.

We urge everyone reading to consider how much value you have gained from the information in the magazine. Has it saved you money? Inspired you to try something different? Entertained you? Helped you understand or solve a problem? If the answer is “Yes”, please become a patron so that we can attract more new readers to the magazine and they can in turn learn without any barriers to knowledge.

Simply scan the QR code to become a patron and support the continued growth and success of the magazine.

Pay it forward and pass on the ability to read the magazine to another farmer.Clive and the rest of the Direct Driller team

Patrons

-

Introduction – Issue 18

There’s quiet confidence in farming at present, and it looks like there will be more money than normal available for investment. Andersons ‘Loam Farm’, their virtual 600ha of combinable crops, is forecast to have a business surplus of £840/ha (on an output value of £1966/ ha) this year compared with £573 in 2021 – but their forecast figure drops to just £161 in 2023. In addition there is money from the Farming Investment Fund – three farmers at Cereals told me they had secured funding – two for drills and one for a shallow cultivator. The question is whether to use the available cash and/or £25k grant to buy a better machine than you had budgeted for, or use the fund money to take the sting out of the purchase.

Pub talk suggests that, when it comes to equipment, the adage “you get what you pay for” applies to complexity rather than reliability, which is of-course the one thing which everyone needs. Not too many farmers calculate and add up the cost of breakdowns, and if they did I think there would be much greater emphasis on pre-season preparation. Doing the preparation job properly means replacing parts such as belts and bearings which are still performing as they should, as well as buying in spares of those liable to pack up. Spares are expensive and there’s a temptation to restrict the pre-season to a oil and filters, worn belts and rumbling bearings, and hope it holds together. Chats with dealers and farmers with the same machines can help list the ‘at-risk’ components.

This where forums such as thefarmingforum.co.uk can be so valuable. Not many farmers would go to the extreme of giving their worn out drill – a Vadersatad 30S – a complete dismantle, repair, paint and rebuild like Jamie Hawkins did last winter. I featured the job in Farm Ideas issue #120. The full refurb cost less than £10k and Jamies knows the 30S suits his existing tractor and field topography – being mounted it goes across slopes better than trailed drills. The record business surplus predicted comes at an uncertain time.

The Ukraine cereal prices are a market abberation (those millions in desperate need of food may describe it differently) which is likely to settle. Farmers across the globe have an amazing ability to respond to change, and in the fullness of time the situation will stabilise. Meanwhile good wishes and good health to all our readers.

-

The Problem with Vegans

Getting a confession out the way. About a third of my meals are 100% vegan. But in balance, an evening dinner rarely doesn’t contain meat. I like to think this is normal. Nutritionally balanced. A healthy diet, that supports a healthy farming ecosystem of arable and livestock. What’s not to like about that? Well, everything if you are vegan. My diet is completely unacceptable. I am uncaring, without empathy, blah, blah. This labelling tends to push me towards believing that outspoken vegans are nutters, who just like the sound of their own voices.

But this is really the problem with vegans: They only care about life above the ground.

Sheep matter, worms don’t. Cows matter, soil microbiology doesn’t. Pigs matter, organic matter doesn’t This being a solid health magazine first and foremost, you can see where I am going. Grazed land has some of the best soil microbiology. “The golden hoof” has been written about many times in these pages. Farmers look to bring in as much manure as possible, as with it comes the biology needed to grow healthy, nutritious and sustainable food. Livestock are an essential part. Yet vegans are usually oblivious to this argument. Because what goes on below ground doesn’t seem to matter to them.

Fields of soy / corn rotations are what’s needed to save the planet. Grown with lots of herbicides and synthetic fertiliser in soils that have lost all their fertility. That is how to get to net-zero. Despite the glaring issue of it not being sustainable or closed loop or near to net-zero. Soil isn’t sexy, it’s hidden away, out of sight. It’s hard to understand the massive impact of what below the ground can have in the world. But it is critical to the argument. Beans, rye, brassicas are all good to have in the rotation.

These crops grown on regenerative farms should be the staple purchases for the like of Huel (the vegan health food). But many vegan food companies seem have little interest in regen ag. Unfortunately, being vegan is enough for them. However, their products could be even kinder to the planet if products were sourced from regen farms. These companies should represent the main sales channels for regen farms – as their goals align with what we can deliver. However, that is not the case currently. But it should be our aim to supply them (at a premium).

-

Featured Farmer – Philip Rowbottom

Philip Rowbottom, is a 3rd generation farmer arable farmer from West Yorkshire.

Some of you may know him as @golfnshoot on Twitter, so it may not surprise you to learn he also owns Woolley Park Golf club and represents team GB in Clay shooting. Here he explains his transition over to Direct Drilling from a conventional plough-based system and how he’s already seeing the improvements across his farm.

“The farm covers around 500 acres just south of Wakefield. Today we farm 300 acres, with the golf course covering the remainder.

The diversification into the golf course was pivotal in how we farm today. Over breakfast one morning, way back in 1991, my father announced we should build a golf course. None of us played golf, or had any real interest in golf, but that’s what we did and that’s what we’ve done for the last 30 years. Built, operated and expanded the golf side of our business. Sport has always been part of my life; I’ve always been competitive. I got involved with the local shooting club, mainly as a way to get away from the farm for a few hours. As I improved, it became more and more competitive and I’ve been very lucky to represent the country, shooting clays around the world.

The farm is still very much part of our business. Being right on the border of a livestock/arable region, we’ve traditionally sold all of our straw, it was becoming increasingly clear to me that our sandstone land needed something putting back. We needed to improve the organic matter, so we stopped selling it and began incorporating it. The change of legislation around disposal of domestic garden waste opened up an opportunity to access compost locally. Over winters we were able to bring 2000-3000 tonnes of compost onto the farm, over a period of five to six years. I knew we were beginning to see very subtle changes to our soils.

Our soils are incredibly abrasive, you go ploughing on the wrong day and you can see the metal wear. Watching how the industry was changing, min- till, zero cultivation, changes in weather patterns, wet seasons, I knew we needed to do something different. In 2020 I bought a subsoiler, we’d never had one on the farm, the wet autumn of 2019 and warm dry spring of 2020 baked our sandy soils, consequently, or wheat yields crumbled. We used the Phillip Watkins Tri-till to establish our oil seed rape crop in 2020, possibly our best yielding rape crop we’ve ever grown.

Subconsciously, I knew I was going to do something differently. Technology has moved on, watching the farming press for a couple of years Direct Drills have moved forward from the Bettison DD we had here 50 years ago, I looked at a few different options, and without having a demo I decide that the Opico Sky drill offered me everything I needed from a Direct Drill. Aside from the benefits mentioned above another factor in the decision making was the looming reduction of the BPS payments, we’ve always done a bit of contracting, I saw an opportunity to be able to offer Direct Drilling service locally. It would be a way of filling that loss of the BPS, its first year has seen around 500 acres with the drill, the hope is to increase that acreage this autumn.

In two seasons we’d gone from plough-based crop establishment, to min- till with the Phillip Watkins Tri-till to having an 4M Opico Sky Drill on farm for autumn 2021 and growing cover crops!

I believe the transition across to Direct Drilling is something I’ve been working on for a number of years. By incorporating chopped straw and adding the compost, changing the soils structure has allowed me to take that step to go down the direct drill route. You often hear farmers say they’ve tried cover crops twice and they’ve failed, so it doesn’t work, it won’t in two years. It takes three to five years, it takes time and perseverance, finding the correct plants for your soils and not just planting one or two varieties either. Between my agronomist and seed supplier, we decided that to grow a six-way cover crop, 40ha into rape stubble, including vetch, clover, radish, rye and phacelia.

Rye was a mistake, especially in milling wheat, I’ll admit. I bottled it, I sprayed it all off, barring a couple of patches in different fields, cover crop varieties are something we need to look at differently this year Slugs were a bigger problem than we’ve experienced on this farm before, yes we maybe should have put slug pellets on at the time of drilling, the Sky drill is all set up to do that, but I’m pretty certain it’s down to the mat of chopped straw, which in previous years would have been moved or buried mechanically, I went straight in with the drill. I’ve invested in a 2nd hand straw rake for this year to see what difference that makes, I’m very happy to admit that I’m still learning, it’s still a bit of a journey of discovery!

We compromised the farm’s rotation when we built the golf course, the rotation of rape, wheat, wheat is what we’ve grown and will continue to do so moving forward, for the time being ,while trying to improve the soil quality with cover crops and using the Direct Drill to establish our cash crops. The farm is only part of my business and it needs to be easy to manage, the direct drill has already freed up time, reduced inputs, certainly on fuel costs, by as much as two thirds already. That is before you add in the wearing metal cost from previous systems and I believe we’ll continue to see reduced costs as the soil health and organic matter improves.

It’s very difficult to quantify, but I’m already starting to see a change to the ecology on the farm, as an SFI pilot farm, the first time we’ve ever entered into an environmental scheme, the wildlife on the farm seems to be increasing from not ploughing, from having green cover on fields between harvest and planting. We’re still learning, we tried broadcasting clover into a wheat crop, sadly it didn’t grow, but we’ll try again this autumn but with the drill as a companion crop. So far, the results have been very encouraging, the crops look as well as they have ever done on the old system, the Skyfall wheat looks fantastic and the oilseed rape looks much better than I hoped it would be. As ever in this job, the proof will be when it comes off the combine and over the weighbridge.

I look forward to updating you on how our first direct drilled harvest turns out later in the year.”

-

What’s Your Colour?

With three trade shows coming in quick succession this year, LAMMA, Cereals and Groundswell, the question of

which colour you like your steel painted comes into focus once again.Written by James Warne from Soil First Farming

Along with the rise of the Conservation Agriculture techniques being adopted on more and more farms across the UK, the choice of zero-till drills seems to grow day-by-day. Significant government support incentives also has an involvement in driving this growth, but without the most sensible outcomes. Machinery manufacturers are showing their ability to design ever more sophisticated machines, mostly based around a disc style opener. Machines are becoming every larger and heavier and demand a greater draft requirement. Very few tine opener machines are available and are clearly not in favour, which needs to be addressed in our opinion.

As usual at this time of year, with wheat now full in ear across the country, the variation in crop establishment can now be seen. Consistent with the last few years a lot of thin zero-tilled crops are evident. The push for later and later drilling exacerbating this effect. This is the disc drill fallacy.

With many soils in the UK now very low in organic matter it has lost the glue which binds it together. Low organic matter soil has generally has poor structure, and tends to slump and compact easily. Without the glue and the structure soil no longer has the porosity for air and water to move freely within it. In our maritime climate there are times when our soils have to cope with prolonged periods of excess water. A lot of focus is put into sorting out failing drainage systems. While this is important, if the soil porosity is not connected to the drains its largely irrelevant.

Too often we see soils which have slumped due to low organic matter, and excess water, being late drilled with a disc drill. More often than not these crops tend to come through the winter low in plant numbers and are unable to tiller adequately to compensate, resulting in thin crops now being visible. Narrow knife style tine openers tend to operate better in the early years of zero-till on low OM soils. Tines will create a little tilth to improve seed to soil contact, whereas discs do not create any tilth. When the soil is moist a disc will actually smear the seed slot it creates further reducing drainage and restricting crop rooting. Seed slots created by disc drills in wet conditions may appear closed at the time of drilling but will open again as the soil dries in the spring exposing the root crown to the air.

With second cereals disc drills can also be problematic when drilling into chopped straw. Do not underestimate the effects of hair-pinning on the subsequent crop. Thin or small-eared second cereals seen now could be a result of the actions taken at drilling. It may not be the fault of a firm soil or lack of moisture or nutrition, it may simple by the wrong choice of drill for the situation.

Overcoming chemical imbalances within the soil can also help alleviate the effects of a soil with poor structure. The water retaining properties of magnesium are well understood.

Magnesium can hold onto 18 molecules of water when fully hydrated. Magnesium also has a relatively large charge density compared to other common soil elements like calcium so water has a greater attraction to magnesium. This tends to keep soils wetter and then dry rapidly, giving greater shrinkage when it finally dries. This shows when the slots open as the soil surface dries as mentioned above. It can also help with structure and porosity improving water movement and infiltration. Understanding how the magnesium and calcium balance is affecting your soil can lead to better decision making around drilling and crop establishment.

In our opinion a tine drill is critical for success in the early years of zerotill. Simple, uncomplicated, low draft requirement tine drills can have a very big impact on the success of zero-till adoption in the UK. The choice of disc versus tine drill at the point of drilling is a critical control point many growers are overlooking. Simple tine drills give great opportunities and low draft requirements even with large output potential.

-

Farmer Focus – Andy Howard

From Drought to Deluge

I am sitting here today (May 24th) listening to Thunderstorms outside. In the last 6 days we have had around 50ml of rain which has been very appreciated. This time last week it was 26 degrees, and the crops were wilting and looking very drought stressed, amazing the difference a week makes. It can stop raining now though!!

Last week I started “Operation Zero Tolerance” for Blackgrass. Apart from a couple of fields our BG levels are fairly low, but for the levels to remain low, I believe the only way forward for us is to not let any plants go to seed. It is a lot of arduous work, which I do not really enjoy but it has been very satisfying to see certain fields that were once a bit of an issue in the past, now have such low levels. There are a couple of benefits spending lots of time out in the fields. Firstly, it gives you time to think and reflect on what you have got right and wrong this year and then secondly, is that you get a chance to really inspect the wheat crops and notice things you would not from the sprayer. One thing that has been noticeable is that our wheat variety blend has coped better the with the drought than the straight Crusoe (see picture). For this reason and the fact that Crusoe is so prone to Brown rust, it has made me think we should be using a variety blend instead of straight Crusoe going forward, let us see what the combine says first.

Talking of Brown Rust brings me onto another subject. At the beginning of the season, I was hoping that we could go all year without using fungicides, unfortunately I have not managed that feat. A couple of fields of Crusoe had brown rust fairly early, which we have had to treat. There is always a reason a plant gets disease and after a sap analysis we discovered that these fields had a shortage of Magnesium and Phosphate which allowed the rust to develop. I probably have not been tissue testing regularly enough this year and did not pick this deficiency up early enough, lesson learnt for next year.

This year we have been using Silica as a foliar nutrient and again we have learned lessons for next season. I was hoping Silica would help us avoid the use fungicides but so far this has not been the case. I have seen silica suppress disease but not to cure it. It seems that once the disease is established in the crop, you must use fungicides. The silica is useful to keep disease out. Where we went wrong was not putting any silica down next to the seed with the drill last Autumn. Also, this spring, we started with the foliar Silica rates too low. Another point, if the rest of the plant nutrition is not balanced, you cannot expect the silica nutrition alone to keep disease out.

This spring I have been experimenting with low Nitrogen rates on wheat. One field has only had 70kg/ha/N of solid N and will end up with two foliar N sprays, so far you cannot tell the difference compared to the rest of our wheat and I am hoping the combine cannot tell the difference either, then I will not need to buy another load of overpriced fertiliser. The spring crops have established well into what was mostly dust at the time. The Bean/OSR intercrop is coming together (see picture). I have failed several times with Spring OSR, but we changed the agronomy this year and it seems to have established better. The linseed with its’ Oat companion is looking great. Finally, our lentil/camelina intercrop is just visible in the rows (see picture). I have never grown Camelina so this could be interesting!!

Hopefully, since this rain we can look forward to this harvest after a couple of difficult years. Long way to go yet though!

-

My Nuffield Journey And Beyond

It’s amazing how one book can change your life. For 2022 Nuffield Farming Scholar Emily Padfield, this one book was For the Love of Soil by Nicole Masters.

Many describe having their ‘eureka’ moment whilst undertaking their Nuffield Scholarship. Although I am only at the start of my Nuffield journey (having undertaken only a few visits). I believe my ‘epiphany’ occurred before I had applied for my Scholarship. I was standing in the lambing shed in March 2021 (only just over a year ago), busily filling a syringe with Pen and Strep to inject all lambs at birth as we had had an outbreak of joint-ill in our early lambing bunch. I had also sourced a probiotic to then give to each lamb to replenish the gut bacteria I was busily killing with the injection.

At the same time, I was listening on Audible (other audio book providers are available) to ‘For the Love of Soil’ by Nicole Masters. The more I listened, the more I realised that what we were doing had some fundamental flaws. To each problem in my life, whether it be animal or crop health, financial, emotional or human health related, I had always looked for a solution, a cure, a ‘quick fix’. What this book made me realise was that we were looking at everything the wrong way round. We needed to stop the problems happening in the first place, or at least understand why they were happening so we could try to prevent them happening at all. From that moment on, my partner Mark (whose family farm we work together) and I started realising there was a different path we wanted to follow.

Never one to hang around (again one of my many flaws) I started to read everything I could about this ‘new’ way of doing things: Regenerative Farming. The more you read, the more you realise there is truth in the adage ‘there’s nothing new in farming’. Mark started remembering methods and ways his grandfather had used, the number of species he had on the farm before policy and economics governed farms to specialise and expand numbers to become more efficient and profitable. He also remembered the plenitude of life that coexisted here before the use of artificial inputs. He recollected the masses of beetles and insects when combining in his old cab-less combine, seeing the grain teeming with life when unloading the auger. He recalled the health of the livestock without all the different products that are now sold to us at huge expense.

A NEW WAY OF THINKING

The first step we took on our journey was to get regenerative advisor and fellow Nuffield Scholar Ben Taylor-Davies to come and have a chat with us on the farm. We outlined what we wanted to achieve, and it seemed to fit with his way of thinking too. We dug holes, took in-depth soil samples, applied lime and gypsum and bought a sward lifter in a bid to get our compacted clay soils in better health. We had re-introduced cattle five years ago by sourcing dairy beef heifers and steers, keeping the heifers we liked to establish a small suckler herd of 40 or so cows plus followers. Up until then, we had been purely sheep for several years, running 800 plus North Country Mule and Cheviot X ewes, lambing in late February indoors.

We are permanent stock fenced on most of our acreage and field sizes are between 20 to 40 acres. Mark has always loathed electric fencing, so this was a major concern for me as I knew getting involved in strip grazing could cause friction. Since our change in policy, I have since sourced some semipermanent electric fencing from fellow regenerative grazier and Nuffield Scholar Alex Brewster at Powered Pasture and also invested in some geared reels for ease of subdividing fields into smaller paddocks.

Due to a bit of restructuring to allow Mark’s sons some land to start their own businesses on, we reduced sheep numbers to around 450 ewes suit our acreage and started rotational grazing with both sheep and cattle, with regular, if not daily moves.

Our grass management fundamentally changed in this first year. No longer did we set-stock or consider short grazing the ‘best’ thing for sheep like we have for many years. We started to look at multi-species swards and planted our first true herbal ley (failing the first attempt, partly by drilling too early and also having an extremely dry spring). Including chicory in pastures was nothing new on the farm, with Mark having re-established a grass ley with a herb rich ley more than ten years ago.

Our grass management fundamentally changed in this first year. No longer did we set-stock or consider short grazing the ‘best’ thing for sheep like we have for many years. We started to look at multi-species swards and planted our first true herbal ley (failing the first attempt, partly by drilling too early and also having an extremely dry spring). Including chicory in pastures was nothing new on the farm, with Mark having re-established a grass ley with a herb rich ley more than ten years ago.

I also undertook a Savory Institute Holistic Management Course through 3LM at the impressive FarmEd facility established by Cotswold Seeds founder Ian Wilkinson. Amongst many other things this helped me keep a ‘holistic context’ central to decision-making processes.

Early into my regenerative journey I found a small herd of crossbred goats, and later in the summer a good number of chickens. I now know you should never get these species without being fully ready and fenced for them, but you live and learn!

Other changes in farm policy have included dropping fertiliser completely although I have to point out we applied very little to silage crops and we hope to at least reduce cattle housing this coming winter through bale grazing hay before having to bring animals in. This year we also pushed lambing a bit later (partly due to my Nuffield Scholarship Conference being early March) and lambed much of our flock outside. We were lucky with the weather but have been extremely pleased with the results so far. I would be confident to say that unless weather turns really ugly next lambing season we won’t be bringing any sheep indoors from now on.

Rightly or wrongly this year we have direct-drilled our AB9 stewardship option, and although it’s early days we couldn’t have wished for better weather. We sprayed post drilling in a bid to get rid of the considerable thistle burden, and I wait with bated breath to see the outcome. Often it’s difficult to reason between traditionally conventional and regenerative methods and I have to admit to getting myself tied in knots over chemical or tillage use. But I do not think that’s uncommon and there are many more established regenerative farmers struggling with the same dilemmas.

THE START OF MY NUFFIELD JOURNEY

Following encouragement from Ben Taylor-Davies, I decided to apply for a Nuffield Scholarship. I had been aware of Nuffield for many years, having worked as an agricultural journalist before meeting Mark and joining him on the farm. I had always held great reverence for anyone who had undertaken a scholarship, and I didn’t expect to get through the selection process, so was ecstatic to be selected. Many Scholars talk about having ‘imposter syndrome’ and I am still very much still experiencing this, but the Nuffield family is such a tight-knit and welcoming one that we have a fantastic support group to rely on.

My topic is: The mob-grazed flerd: Improving soil, biodiversity and farm incomes. A ‘flerd’ is a mixture of species running together as one flock or herd. We haven’t cracked it quite yet, although we are currently running sheep, cows and goats as one group. The chicken tractor is being built as we speak. I am hoping to visit farmers who are successfully grazing animals together like this, however I appreciate there are limitations so it’s a question of whether it’s even a good idea.

So far, I have travelled to Kansas to the No Till on the Plains Conference (I urge you to attend if you haven’t already), visited many mob-graziers in England and travelled the length of Scotland visiting like-minded livestock farmers. I travel to Portugal in June and in October I, alongside a number of other Scholars, will visit the Savory Institute in Zimbabwe before heading to a number of ranches and facilities across the country before heading onto Zambia. I am and will continue to be forever grateful for the wonderful opportunity that a Nuffield Farming Scholarship has given me to travel and learn how to be a better farmer. I am also passionate about communicating what I learn to others in the industry.

I hesitate to bang the ‘regenerative farming’ drum. I believe in all its concepts and realise it embodies so many aspects, but I am acutely aware that it is dangerous to create a ‘them’ and ‘us’ discourse amongst farmers. We are all striving for betterment together. I just want to be a good farmer. Good to our soil, our environment, our animals, our crops, our consumers and ourselves.

2023 NUFFIELD FARMING SCHOLARSHIPS

• Applications for 2023 Nuffield Farming Scholarships are now open online until 31 July 2022 and can be completed by visiting www.NuffieldScholar.org and clicking the “Apply” button.

• Nuffield are hosting a series of “open sessions” this summer for potential applicants to ask questions and get help to complete their applications.

-

How Nutrient Status Impacts Plant Health

In the second part of Direct Driller’s series exploring sap analysis, Mike Abram finds out about the science behind

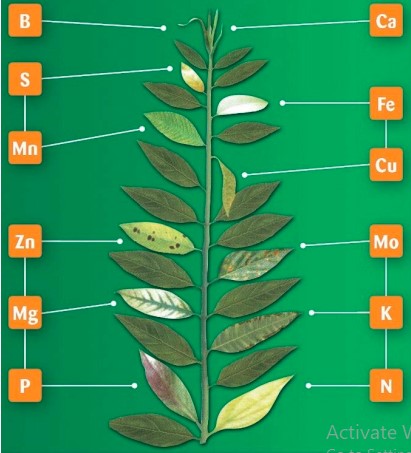

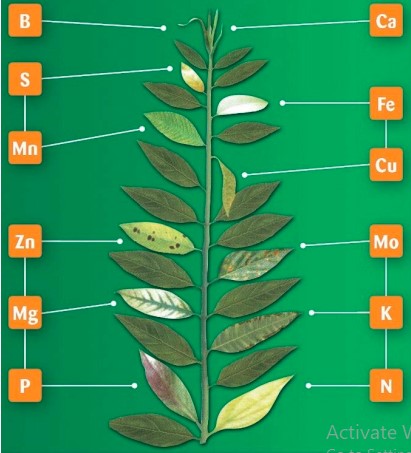

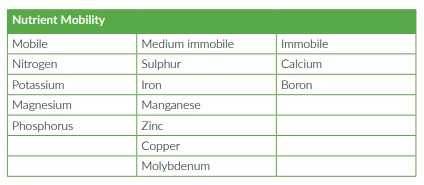

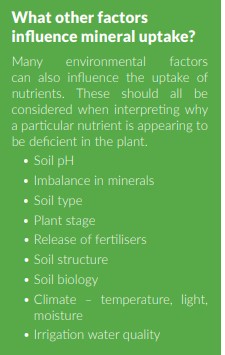

nutrient use in plantsNutrients are vital for life but if they get out of balance it can cause either deficiencies or excesses that restrict plant productivity. Sap analysis is a tool to help growers understand the nutrient status of plants at the time of sampling and can highlight potential problems earlier than waiting for visual symptoms. Understanding nutrient status requires knowledge of how mobile they are within the plant. One of the unique things about sap analysis developed by companies like NovaCropControl and more recently offered by Eurofins is that it compares sap from old and new leaves.

Once inside the plant nutrients are transported to where they are needed, typically the plant’s growing point, explains Eric Hegger, a consultant with NovaCropControl.

But some elements in the plant are mobile, while others are immobile. The immobile ones get locked in place and do not move around, while the mobile ones can move from their original location in the plant to areas of greater demand – e.g.: the growing point. That means deficiencies will show up first in different leaf layers depending on nutrient mobility, says Mr Hegger. “For the mobile elements, nitrogen, potassium, magnesium and phosphorus, deficiency will always show up first in the old leaves.

“At the moment there is not enough uptake of these elements, the young leaves will take them from the older parts. If you look at plant sap analysis in this case you will see that young leaves stay high enough, but the old leaves start to drop down, which eventually gets to a deficiency level. Only analysing the middle or younger leaves means you won’t see deficiency as quickly.”

The opposite is true for immobile nutrients – deficiencies start to show up first in younger leaves as the plant can’t remobilise reserves in older leaves. For the medium immobile nutrients either can be true depending on different factors. “That’s why we ask for both young and old leaves as it tells a lot about every element and about nutrient transport. “For example, if it is difficult weather, such as high temperatures or high light intensity and the crop is suffering. In that case plant sap analysis will show levels building in the old leaves because the plant still takes up nutrition, but it can’t be transported to the new leaves as the plant is protecting itself from too much evaporation.”

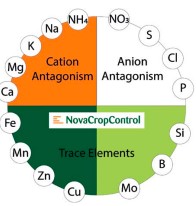

Nutrient balance and interactions in the plant

The next important factor to understand is that there is competition between some sets of nutrients within the plant. Calcium, potassium, magnesium, sodium and ammonium are all positively charged ions, or cations, while nitrate, chloride, sulphur and phosphate are all negatively charged anions. If the uptake of all the cations is in balance, then the plant’s nutrition is balanced. But when one element’s uptake is higher than the plant needs, that will block the uptake of all the other cations, Mr Hegger says.

“For example, if you have higher uptake of potassium because of an application of manure, that will block the uptake of the other cations.”

So in the sap analysis, if you see potassium is higher than the target values, and calcium is lower it’s probably because of the high potassium rather than inadequate supply of calcium, he explains. Within the cation balance, potassium is usually the element most likely to be too high, although sodium can be too. “Potassium is like candy for plants, and is taken up very easily, whereas the plant finds calcium and magnesium harder to take up and is highly related to a healthy growing crop.” Keeping potassium and calcium in a good balance is important for fruit quality, he notes. Calcium is important for cell strength, while potassium for filling fruits. “If there’s not a good balance that will influence fruit quality.” For example, if the potassium : calcium balance is tipped towards too much potassium that can cause skins to split, whereas too much calcium is responsible for gold flecking on tomatoes.

Comparing the balance between the cations is important for understanding nutrient balance within the plant, and which nutrient to focus on. “One of the common mistakes is focusing on elements that are too low in the plant or soil, whereas it might be that element is being blocked by another one and that’s what you need to focus on, and it won’t matter how much you apply.” Anions work the same way. Too high chloride, for example, could block nitrate uptake, while there are similar interactions for some trace elements, especially iron, manganese, zinc and to a lesser extent copper. “Manganese can easily be too high in a plant and block the uptake of iron and zinc.”

Just to complicate the picture a bit more, there are more interactions between elements beyond just within those groups, as detailed in Mulder’s Chart.

“For example, just looking at calcium, that sulphur, manganese, nitrogen, phosphorus, boron, iron and zinc influence calcium uptake. “Sometimes you could compare the analysis with dominoes – if one element is too low, there’s a good chance it will influence all the other elements as well.” But while that can complicate the picture, Mr Hegger stresses that looking at the cation and to a lesser extent the anion balance is the crucial starting point.

“In 80-85% of cases looking at the cation balance will be enough. Focusing on this will help get the plant in better shape.” If the plant doesn’t respond favourably to changes in management, that’s when digging deeper might be required, he concludes.

How are the target values for each nutrient calculated?