If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

AMAZONE – THE PEDIGREE IS THERE WHEN IT COMES TO MINIMUM DISTURBANCE DRILLING

When it comes to what’s currently trending in crop establishment, the focus is very much on plant nutrition and the targeted application of N & P fertilisers along with the seed to bolster root development and to enable the plant to grow away strongly from pests and diseases. Multi-hopper seeders now offer that flexibility of being able to combine different seed types, add a starter fertiliser or the addition of slug pellets or a micro-granular herbicide simultaneously with the drilling operation. Seeding depth can be split into different zones as well by the addition of a second or third material entry point.

In the area of reduced tillage drilling, three drills stand out strongly in the AMAZONE range, all featuring that multi-hopper format: the Condor direct tine seeder, the Cayena tine seeder and also the Primera DMC. Since the late 1970’s, AMAZONE have pursued their chisel opener philosophy when it comes to reduced tillage seeding systems. After numerous field trials in those early years, Dr. Heinz Dreyer, father of current joint owner of the AMAZONE Group, hit upon his successful formula of running a hard-faced chisel opener to place the seed in the ground rather than using a disc. This avoided crop residues being hairpinned into the seed slot and generated a slight tilth which improved seed/soil contact as well as mineralising some nitrogen in the seed zone to improve plant development. The principle of the NT chisel opener continues today in those Condor, Cayena and Primera drills.

The Con-dor, with three stagger of coulters and a row spacing of 25 cm or 33 cm, makes it ideal for inter-row mechan-ical weed control and comes in working widths of 12.0 and 15.0 m. The Cayena, again with three stagger of coulters, a covering harrow followed by a targeted reconsolidation, is widely renowned for its low horsepower requirement and ability to run in many conditions, is in 6.0 m only whereas the Primera DMC is available in either 3.0 m or 6.0 m widths.

Featuring at Groundswell this year will be the Primera DMC 6000-2C The Primera 6000-2 DMC is more than just a direct drill as does what it says in the name, DMC – direct, mulch, conventional. Huge underbeam clearances, and the openers in banks of four rows, mean that copi-ous amounts of straw and cover crop can pass through the drill without any fear of blockage. Each chisel opener closely follows the ground contours via a parallel linkage – guided by individual hoop rollers behind the coulter with the depth set mechanically on a spindle. The narrowness of the chisel opener means that little soil is disturbed but the seed slot is left clean for good seed / soil contact and the micro-tilth generated by the chisel action can then be pushed back into the groove by the angled hoop rollers following. On the rear, a choice of either the Roller harrow, for light dry conditions or in the spring where moisture conservation is cru-cial, or the wellknown universal Exact harrow, is used to finish off the seedbed profile.

The 4,200 litre split hopper, carried on flotation 700/45 -22.5 tyres with its twin electrically-driven metering systems, can feed both seed and fertiliser down to the coulter. The Primera 6000-2C weighs in at just 6,500 kgs and pulling power is a modest 180 hp for the 6m drill and, due to the little amount of soil-engaging parts and the robust-ness of the construction, the drill suffers from little wear and tear.

New for 2022 is the option of the GreenDrill 501 catch crop seeder box which now can be added to make a third hopper. The GreenDrill can be specified to broadcast seed on the soil surface ahead of the Roller har-row or can apply a third material down the sowing coulter. The electrically-driven metering system is com-bined with the other two hoppers and is controlled via the ISOBUS software and can be run off a third VRA application map. On the headlands the three hoppers can switch off at different times using the unique Multi-boom software.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

INDIVIDUAL PLANT DETECTION – CAMERA SYSTEMS WITH A FUTURE?

Camera-based plant protection – the technology already exists but where do we stand when it comes to using it in practice? HORSCH LEEB has been carrying out tests in this respect for quite some time. Theo Leeb tells us about the challenges and the chances.

What is the state of technology with regard to individual plant detection?

‘Theodor Leeb: At the Agritechnica 2019, some startup companies already presented camera systems for spot spraying weeds. This made the expectations of customers, manufacturers and also of political decision-makers rise.

In the past few years, we tried to shed light on this topic and to test where we actually stand. To begin with, spot spraying with optical sensors or cameras is not basically new. This method has already been used for about 20 years in the typical no-till regions with low rainfall like Australia, Russia or Kazakhstan – namely in the “Green on Brown” sector. Another method is “Green in Green”. So the technology already exists. The question is which system really makes sense when and where.

What does “Green on Brown” and “Green in Green” mean?

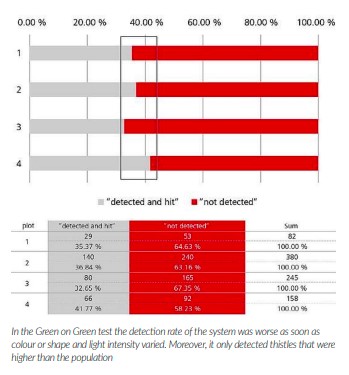

Theodor Leeb: There are two principles: “Green on Brown” and “Green in Green”. Brown corresponds to the arable soil and green to the plant – whether cultivated plant or weed. The topic Green on Brown has been existing for quite some time. Among others, some manufacturers offer systems for the application of glyphosate before sowing. This method is mainly used in no-till regions. With the Green in Green method, you have to differentiate between cultivated plant and weed. And partly you also get the information what kind of weed it is. With regard to the question how far we have come with this topic: We carried out some tests this season and also last year. With regard to Green in Green we for example tried to spray thistles in wheat. Thistles normally appear in nests and not on the whole field. This would be a typical application for spot spraying. With the test, we wanted to find out how exactly the system detects the thistles and what hit rate we would achieve. We basically can only say that the system works. The thistles were detected but only partly. The hit rate ranged between 40 and 60 %. The question, of course, is if this is enough. In my opinion, it still is far from being field-ready. Moreover, as a farmer you wonder about the weeds that still are on the field – are they tolerable or not? This, of course, also depends on the kind of weed, but it should be clarified.

Were the thistles not detected or did the system not react fast enough and the thistles,

thus, were not hit?Theodor Leeb: In the test, we differentiated between “detected but not hit” or simply “not detected” and ogically not hit. But this also is a question of the calibration of the system. AT a 36-metre boom there are a total of 12 cameras which are mounted every three metres facing forward with a slanting angle. And the nozzles are assigned to each camera according to the spatial arrangement. It is a rather complex procedure to calibrate the individual camera positions to make sure that the appropriate nozzle opens at exactly the right time.

But the real problem rather is that the thistles indeed are not detected by the system. The biggest challenge are the different lighting conditions. I.e. there is a difference if it is cloudy or sunny, if you have to work with or against the sun etc. And the weather conditions in turn influence the shape of the thistle. The leaves for example roll up a little bit in case of a high solar radiation resulting in a significantly lower detection rate. So what we found out was that there still is need for optimisation.

How could the system Green in Green be improved to make it work?

Theodor Leeb: You have to know that there is an AI behind it. An incredible amount of training data is required to make sure that the system always detects the thistle. You need photos and data from thistles in all shapes, in all lighting conditions, growing stages, from all different thistle varieties etc. We are talking about thousands of photos that have to be analysed and labelled manually. Every pixel has to be assigned correctly. This is an enormous manual effort and finally the crux of the matter. The more labelled photos there are, the more exactly and reliably the system will work.

And a thistle is rather easy to detect compared to other plants.

Theodor Leeb: Exactly. The human eye can detect it rather easily and a human can also differentiate it. The difference between monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants is quite obvious. But if you want to differentiate for example black-grass from wheat it is getting difficult. This is where we possibly reach the limits of what is feasible.

But there are further technical restrictions. An important point is the spot size, i.e. the smallest possible area that can be sprayed. In theory, the biggest savings potential would be if we treated every little weed with an effective spraying area of for example 5×5 cm. However, as we work with sprayers where the nozzles are mounted with a spacing of 50 cm or 25 cm, there is minimum spot width of approx. 60 cm respectively 35 cm depending on the nozzle layout. As the nozzles cannot switch infinitely fast, the spots in the direction of travel are about 50 cm long. If the distance between the weeds is smaller than 50 cm, the system will not turn off. Thus, for the savings potential the ratio of spot size and weed infestation is essential.

Physics respectively optics are two other limiting factors. Let’s take beets as an example: It is important to detect weeds at an early stage, i.e. when the size is one centimetre or even smaller. In theory, it is possible the detect this tiny plant with the system if you drive very slowly and can really look at it from all sides. But in practice, operational speeds of 10 km/h and more are common. To achieve a sufficient reaction time, the cameras face forward at a slanting angle. But if there is a large clod in front of the small weed or if another bigger plant hides the weed, the camera will not be able to detect it. So you cannot achieve a hit rate of 100 %. Now the question is what is acceptable. Are 90 % enough? At the moment, we simply do not know.

As thistles do not grow in the whole field but in nests, they are ideal to carry out tests with spot spraying. In the test, we analysed the hit rate of the system and if the thistles were detected.

So at the moment the topic is limited by the training data and physics.

Theodor Leeb: Yes, but there is another exciting question we have to clarify. In many row crops it is good professional practice to apply a soil herbicide after sowing. This guarantees a basic protection for a certain time. The weeds that emerge after two to three weeks then are treated with foliaceous agents. If you decide to do without the soil herbicide you logically have to wait until the weed has grown so that a camera can detect it. Let’s assume that we use the spot spraying method to apply a foliaceous agent on the emerged weeds: The problem is that the foliaceous agents affect the development of the cultivated plant. You cannot avoid spraying on it if the weed for example is close to the beet. Moreover, new weeds are constantly emerging all along. So the question is: How often do we have to spot a certain area to make sure that for example a beet field remains clean? We have not yet tried to do without the soil herbicide. But in my opinion, for beets, it does not make sense to do without it.

A reasonable solution would be a combination, i.e. a soil herbicide as the first measure and the other treatments with camera-based spot spraying systems. Another rather exciting idea is to accept a certain economic threshold respectively to tolerate certain weeds that are classified by the camera as they do not pose a problem in the next season due to a cleverly chosen rotation or because they are easy to treat. I think this might provide the biggest savings potential. However, it still requires a lot of development as the weeds do not only have to be detected but also have to be classified.

You have just been talking about herbicides. Can you image other sectors where this

method could be used?Theodor Leeb: In case of plant illnesses for example you could apply fungicides or even growth regulators in cereals in a site-specific way. However, this does not require such a finely itemised spot spraying system as in this case we are talking about a larger area. For this application we use our pulse system PrecisionSpray with a variable application rate per 3 metre boom section. But there are approaches to use the cameras to detect illnesses. The question rather is if it is not too late at that time. In my opinion, the approach via biomass and weather models would be more productive.

How does “Green in Brown” work?

Theodor Leeb: Together with a manufacturer from France we carried out tests. The method is based on a mere differentiation of colours, i.e. you have a camera image and analyse which pixels are green or brown, thus plant or field. The green areas are sprayed. This worked quite well, however this system is not of major importance in Central Europe as we usually carry out tillage and as the conditions are wet.

Could you explain this in more detail?

Theodor Leeb: On the high-yield sites stubble cultivation is usually carried out after the harvest to mix in the straw. After a few days or weeks volunteer crops and weeds emerge. I.e. the field more or less is green all-over. Spotting does not make sense as the plants are too close to each other. So you would have to treat the whole area and could not rely on point application. In dry regions where no-till farming is very common this is different. There is no tillage after the harvest. As it is very dry there are little weeds or catch crops. And in this case, you can – instead of spraying all over – work with a camera system in a targeted way for example to save costs when using glyphosate for spraying the individual plants.

In addition to Green on Brown and Green in Green there is another differentiation: offline and online methods. What I have described so far are online methods, i.e. the camera is mounted on the boom and while driving the system decides whether to spray or not. With offline methods you get the information by means of a previous scanning. You normally fly over the field with a drone that is equipped with a high-resolution camera and scan the field from a height of approx. 20 m. At the moment, an algorithm is used to differentiate weed from crop in the high-resolution photo. This system provides an application map with the sections that are to be sprayed. This information then is loaded into the terminal of the machine and the field is treated. It works similar to the application maps for fertilisation.

Together with a start-up company we also have made tests with offline system for quite some time. The system basically works, but there also are a few obstacles. For example if you want to spray you have to have current data. There is little point in flying over the field with the drone 14 days in advance as in the meantime the weed infestation will change. The other obstacle is a physical one. Because of the offset method the spots have to be larger to hit the weeds as the GPS tolerances of the drone and the sprayers add up. Larger spots in turn mean that the sprayed area is larger, too, and thus there is less savings potential.

The extremely high data volume is an additional challenge. Endless gigabytes per hectare are generated that are sent to a server for calculation. This often takes the current internet connections to their limits. On the other hand, the application maps have to be sent back to the terminal of the farmer. Depending on the number of polygons (spots) the current ISOBUS terminals only allow for applications maps with a size of less than 5 hectares.

This means: From a technical or technological point of view the offline method can be displayed. For practical use, however, some more time is required to optimise the processes. And first of all, we need solutions for the high data volume. We possibly even have to find a parallel solution to ISOBUS.

What is your summary?

Theodor Leeb: In my opinion, spot spraying is the next logical step to meet the future requirements with regard to Green Deal, environmental protection and sustainability. Consequently, we come from an all-over treatment over band application to small-area spot spraying. The objective always is to apply the agent only where it is really required. In this respect, a camera-based system – whether online or offline – can make a valuable contribution.

We are intensely working on an optimisation of these systems and we will continue to carry out tests to gather more experiences. Our task is to transfer everything that is possible from a technological point of view into practice in such a way that the farmer can safely and simply use these methods in his everyday working like. Thus, spot spraying can become another component with regard to the optimisation of conventional crop care. But I also see the limits of what is possible as in the field we do not have standard, industrial and constant conditions.

My summary is: nature still will be nature. And nature cannot be constrained by industrial or digital standards.

-

Farmer Focus – Andrew Ward

Direct drilling into heavy clays is a battle still to be won

Eight years of trials with cover crops and direct drilling has prompted more questions than answers.

The soil advisers at Agrii like to remind me that there is more to direct drilling than simply placing the seed into uncultivated ground. “You have to earn the right,” they tell me in reference to the need to first get the soil in to a condition where it will perform as expected. In my experience, ‘earn’ is an understatement. When the day comes that I am truly happy with how my direct drilled crops look and with the financial returns they deliver, it will be because I have battled hard to create that situation. This is not to say that I cannot grow crops by the direct drilling method. I can. In some years the financial returns are even reasonable, but as yet no direct drilled crop on this farm has produced a net return better than that sown after the ground was first cultivated with the Simba Solo. This is the root of my frustration.

I started on this journey to identify a direct drilling approach that worked on my heavy clay soils eight years ago. I selected a 22-acre field close to the home farm at Leadenham because it was near enough that I could monitor it regularly and at my convenience. The soil type, structure, and everything else was typical of many of the fields on my 1600-acre farm half of which is 50%+ clay. I’ve used this field to investigate a range of establishment regimes, species of cover crop and following crop options. Some have worked better than others, but I’ve also had two complete crop failures. This is turning out to be an expensive exercise, but I’m also relieved not to have followed the crowd and gone ‘all in’.

In harvest 2021, the long-term cover crop/direct drilling field produced a net return that was £180/ha less than the field immediately next to it which serves as the yearly comparison and where the crop is produced following the farm standard regime. This poorer financial performance reflects the cost of an additional pass to sow the cover crop, the costs of the seed itself, one or two applications of slug pellets and the lower yield of the spring barley crop. It amuses me that DEFRA is offering to pay £40/ha to farmers to sow cover crops.

This is only a small contribution to the true cost these crops have within my business and I for one will not be signing-up for any of the cover crop options on offer as part of the sustainable farming incentive. Like many, my motivation for direct drilling is to cut costs and save money. If I need to invest in new machinery, extend the rotation or bring in cover crops, then so be it. So far, my experience is one of ‘two-steps forward, one-step back’. This is far from the resounding success that many preach.

Cover crops are a case in point. After several years of seemingly making good progress and a small but noticeable improvement in soil condition, disaster struck. Come the spring, the ground was rock hard, and the spring barley crop suffered at best 15% germination. It was abandoned. We soon learned that without a gentle cultivation in the autumn to create a fine tilth, there is little chance of successfully establishing a cereal crop come the spring. We’ve also tried lightly grazing the cover crop with sheep – two to three days at a low stocking density – only to find they tread the ground too much and you lose the friable tilth. This neatly sums up my experience: direct drilling into heavy soils carries a high risk. The friable tilth created in the autumn needs to be preserved until the spring.

Having tried drilling cover crops directly into stubble and broadcasting the seed with a pneumatic spreader before rolling in, on the advice of others, I moved to a wide-row system. We had modified an old Simba Solo for use as an oilseed rape drill and fitted it with low-disturbance tines designed by Philip Wright of Wright Resolutions. The seed is sown in 45 cm rows before a Simba Unipress fitted with spring tines is pulled behind. This approach seems to be working well, so far.

Maintaining output

In most years, the clay soils tend to produce the highestyielding crops, but also require more work and horsepower. This is my dilemma: I want to maintain the output of this land but reduce my reliance on big tractors and heavy equipment. I willingly concede my Simba Free-flow drill has its limitations. This is not to say that I haven’t used it successfully to sow direct-drilled crops. I have and most of the crops that followed have been good, but it is not suited to drilling directly into cover crops or into autumn stubble where there is a thick layer of trash. In contrast, it works better where the ground has been lightly cultivated with the Simba Solo or in overwintered stubbles when the straw is less fibrous and partly decomposed.

It’s not that I can’t direct drill on heavy soil. In spring I can, but I’m finding direct drilling in the autumn on my heavy soils to be a challenge. By adding another, more suitable drill, to my list of implements I fear I will incur higher establishment costs, which need accounting for, and lower output. This is not a proposition I find acceptable. It is my desire to find a drill that I can use in the autumn, perhaps after beans and oats, to direct drill a cereal crop in to standing stubble and a cover crop. Such machines already exist. Those from Weaving, Amazone, Horsch and Horizon are all capable of drilling directly into stubble as well if not better, than my Simba Free-flow.

I need a mounted drill, probably a 4- or 6-metre, that complements my setup and gives me another option. My issue is the cost. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve heard someone say they’ve spent £150,000 on a drill only to claim they’re saving money. In contrast, I paid £19,000 in 2016 for my 8-metre Simba Free-flow and I would argue that my crops are more profitable. I can cultivate many acres for £150,000 and not suffer any yield penalties! I plan to keep this drill going for as long as is practically achievable. If in time, carbon credits are as valuable as a tonne of wheat then I realise my system will need to be reviewed.

Good soil structure

All soils suffer from compaction and while I have seen instances that some soils will ‘self-structure’, it is my belief that some form of intervention such as that involving a tine or sub-soiler is required periodically. This is especially so on the heavier soils. On the light and medium land, we grow sugar beet while elsewhere we sow oilseed rape using the modified Simba Solo, so it could be argued that remedial action of the sort I consider necessary is performed on a periodical basis as part of the rotation. Some our land destined for spring crops is cultivated in the autumn using the Simba Solo. Once there is a good flush of weeds it is sprayed off ahead of the winter. While my system works, I realise that to successfully sow through a cover crop in the autumn and in high trash situations, I need another drill.

To find a drill that could work in my system, this spring I hosted a drill demo in association with Agrii. The day attracted about 280 visitors, so clearly there are others like me. The demo field will be taken through to yield to see if the different drills were affected more or less by the conditions than the Simba Free-flow. Behind the demonstration drills, we made a pass with a straw rake. This is a reasonably inexpensive attempt to improve seedto-soil contact, improve water penetration and promote the efficacy of residual herbicides. It is already clear that on seven out of the 10 drills in trial, this tactic has increased germination by up to 15%.

I am also mindful of the continuing loss of plant protection products seen as essential to the profitable production of crops. I’m not suggesting that direct drilling will reduce the need for fungicides. It may even increase the incidence of certain diseases such as net blotch given that infected stubble is the primary source of inoculum, but I believe that the need for certain herbicides can be reduced. We rely heavily on glyphosate and although I have got on top of a black-grass problem, we are now seeing worsening situation with Sterile brome. We cannot continue to rely so heavily on herbicides to keep on top of problem weeds. Moving the soil less frequently should run down the weed seed bank and gradually reduce the amount of herbicide needed. Our current strategy has enabled us to achieve 99% black-grass control for £90/ha mainly through a move to roguing which has led to a 30% reduction in herbicide use.

It irritates me that for some of my industry cohorts, ‘direct drilling’ has become a new religion. The vitriol and other comments I have seen directed at some who question the merits of this approach is shameful. It stifles open debate and is bordering on abuse.

-

Early Cover Crop Benefits: What Can You Expect In The First Year?

Written By Laura Barrera and first published on AgFuse.com

In 1995, Pennsylvania farmer Steve Groff was speaking at an event when he asked the audience the question:

Do cover crops pay off?

His thinking at the time was that he had been no-tilling since 1982, and maybe if he no-tilled long enough, he wouldn’t need them. Ray Weil, a soil ecologist with the University of Maryland, happened to hear his question and approached Groff about doing a cover crop study on his farm. It turned into a 12- year project, from 1995 to 2007. It was in 1999, four years into it, Groff got the answer to his question. That was the year he had a drought, and the corn that was grown on previously cover-cropped ground out-yielded the corn on non-cover cropped ground by 28 bushels per acre.

“That’s all I needed,” Groff says. “Ever since that I’m totally committed to cover crops.”

Talk to most farmers who have been using cover crops and you may get a similar story. They’re a long-term practice for protecting and improving the soil, which may also translate into protection and improvements for cash crops. The longer you use them, the more likely you’ll see a return on investment. But what about the short-term? Are there benefits growers can experience in their very first year of using cover crops? The answer is: it depends. A variety of factors can influence the early benefits of cover crops, including the soil’s current health and conditions, tillage practices, species selection and overall management.

The poorer the soil, the faster the results

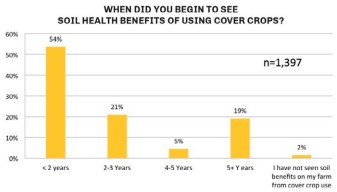

One of the fastest changes that can occur from cover cropping is the improvement of soil health. In the 2016- 2017 Cover Crop Survey Annual Report, 54% of farmers said they believe that soil health benefits from covers began in the first year of use. While covers can help any soil, Groff, who now runs a cover crop consulting business, says that cover crops seem to help a poorer soil quicker.

“If you have 3-foot deep topsoil in Illinois, you’re not going to see a dramatic difference in the soil as you would in maybe another soil that’s on a hillside, or rocky, or sandier,” he says

Eileen Kladivko agrees. The Purdue University agronomist says that one of the earliest changes farmers may see in their early cover-cropping years is an improvement in soil aggregation, especially in soils with low soil tilth and organic matter, such as 1.5% or less.

Another potential early benefit is less soil crusting, which can result in better seedling emergence and uniformity. “It depends on the year, it depends on the soil,” she explains. “If you have a severe thunderstorm shortly after you’ve planted and before your seedlings have emerged, having something like a cover crop on the surface can reduce that issue.” That goes in hand with preventing erosion, especially for those growing low-residue crops like tomatoes, corn silage or seed corn.

“And those are also places where cover crops are easier to fit in because they have more time after harvest,” Kladivko says. “You can actually get more growth and different kinds of cover crops, because you’ve got a longer window in the fall to get things established than if you do if you wait until after field corn harvest to seed the cover crops.” She notes that some of these possibilities would be more obvious for famers who are tilling than for no-tillers. “If they’re in no-till and they don’t have any significant erosion problems, then they may not notice that kind of benefit.”

Preventing rills and gullies pays off

While it’s difficult to calculate a return on investment for most of these early cover crop benefits, one effect that can result in a direct economic benefit is the prevention of rills and gullies. One farmer told Kladivko he usually had to fix the beginning formation of rills and gullies on his highly erodible soil. But just one year of cover crops prevented them from forming, saving him time and fuel. “Even if you don’t worry about how much soil is washing down the river — how much of that $10,000 an acre soil you just let leave your farm — the fact that you had to actually go and do something with the beginnings of a gully, to this farmer was worth time and money,” Kladivko says.

Trapping nitrogen now for future crops

Kladivko admits that this does not pencil out for a farmer who is renting land and is looking for a return on one year of cover crops. But for those who own land or will be farming ground for several years, cover crops can keep nitrogen from leaving the field and build up their soil nitrogen bank account. “If 20 pounds of nitrogen was just going down the drain, now you’re keeping it in the field,” she says, adding that covers can scavenge up to 30 pounds of nitrogen. If you’re growing a legume, it’s even more.

Unfortunately, growers can’t “withdraw” from that soil nitrogen bank in the first three years. Most of the nitrogen is recycled into the soil organic matter, Kladivko says, but at some point there will be enough built up that farmers can cut back on their nitrogen. “It’s certainly going into that account, they just can’t draw on it.”

Cover crop top growth can aid water availability and weed control

It depends on how much cover crop growth there is, but if farmers end up with a good mulch from it, that can increase soil water infiltration rates, Kladivko says. It can also reduce evaporation rates from the soil, which means there’s the potential for greater water availability for the cash crop at some point in the summer. “The rainfall that you do get will last you a little longer,” she says. “That’s a potential benefit in year one, depending on the year and on how much topgrowth they allow.” The amount of cover crop topgrowth can also help in the fight against weeds, particularly those that may be herbicideresistant.

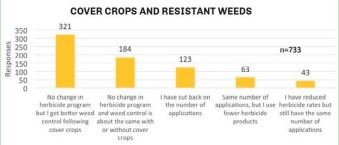

“I know some of our weed scientists at Purdue get very concerned with people saying ‘You’ve got cover crops, you don’t need any kind of herbicide or weed control, that’s all you need,’” she says. “But they say it can provide another tool for weed control in addition to herbicide. For winter annual weeds, I think in general they think they can be pretty effective.” In the 2016-2017 Cover Crop Survey Report, 44% of farmers said that while they’ve made no changes in their herbicide program, they’re getting better weed control following cover crops.

Best cover crops to begin with

For farmers who are hoping for benefits from the get-go, Kladivko says grasses like cereal rye, wheat or barley, are good ones to start with because they grow faster and have fibrous roots. “Something with a fibrous root is going to help hold that soil together and help provide good cover,” she says. For growers looking for some additional weed control, Groff says that cereal rye before soybeans is a good fit. In fact, the Cover Crop Survey Report specifically asked respondents about their experience with cereal rye on herbicide-resistant weed control, and 25% said they always see improved control following cereal rye and 44% reporting “sometimes.” The remaining 31% said they never see improved control.

Groff also recommends pairing oats with radishes, calling them the “cover crops with training wheels” because they’re hard to screw up. They also provide tangible benefits to the soil early on — the word Groff most often hears from growers is “mellow.” That mellowness is more noticeable with radishes because their deep taproot help alleviates compaction, but oats will also improve the soil tilth as its roots die in the spring. Kladivko recommends that radishes not be used alone because their size can leave the soil erodible. Management of the two is easy because they’ll both usually winterkill, so farmers don’t have to worry about having to deal with a living crop in the spring. “It’s easier to plant into, you don’t need special equipment on your planter,” Groff says.

But they do have to be planted on time — at least 6 weeks before your average first killing frost — to achieve decent growth, which may be a challenge for farmers with later harvests in northern locations. Black oats are another good beginner option that can be easily terminated with Roundup or a roller/crimper and decompose quickly for easy planting conditions. Legumes are another species Kladivko recommends for improving the soil structure, but unless they’re established early — in a corn-soybean rotation, they would need to be seeded before either crop was harvested — then they won’t achieve much growth in a fairly short window. In that situation, a grass is a better option.

4 tips for succeeding with cover crops from the start

Groff warns that while cover cropping is a simple concept, being successful with it is very complex. Below are some tips he has for setting yourself up for cover crop success.

1. Treat your cover crops like your cash crops. In all aspects, which includes preparing to plant them, knowing when to plant, and understanding that in some years it’s not going to be as good as others. “Cover crops are just like cash crops,” he says. “Some years they’re phenomenal results and some years they’re lacklustre due to weather and mismanagement.” He adds that cover crops will make a good farmer better and a bad farmer worse. “Just because you have a bad year of cover crops doesn’t mean that you’re a bad farmer,” he explains. “It just takes another level of management. If you treat your cover crops like your cash crops, you’ll stand a much better success rate of making them pay and making them work.”

2. Create or fulfill an existing planting window. Farmers who take wheat off in the summer and don’t follow with a double-crop have the easiest way of jumping into cover crops because they have a wide window of planting and cover crop growth. But for farmers who are growing something like full-season corn and soybeans, their options — and chances for cover crop success — become more limited. “Maybe you need to plant a field of shorter season corn or shorter season soybeans — take them off a week sooner, you’re setting yourself up for success then,” Groff says. “Because we’ve got good varieties out there now that are short-season, you’re not going to really sacrifice yield if you get the right one. You’re setting yourself up for a timely planting where you can actually see a difference. Success depends on management.”

3. Find a mentor. Anyone starting out with cover crops should find a mentor, and that doesn’t necessarily have to be a personal relationship, Groff says. Instead, farmers should look for the people who are achieving what they want to achieve and follow what they do.

4. Choose your own way. Everyone wants a cover crop recipe, but Groff says that like all other aspects of farming, farmers have to figure out their own road map.

“Just like you choose the corn hybrid you plant, the soybean varieties you plant, you don’t plant the exact same thing as your neighbour probably,” he says. “Eventually you’ll do what works on your farm, and that goes from species to seeding rates to creative ways to get them planted sooner.”

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

JOHN DEERE SEE & SPRAY™ ULTIMATE – TARGETED, IN-CROP SPRAYING

With See & Spray Ultimate, you can gain cost efficiency in your herbicide applications by reducing your spray volume, which in turn enables you to use more advanced tank mixes. We have added to the previously launched See & Spray, to allow in crop targeting of weeds (See & Spray was for fallow ground only). See & Spray Ultimate currently only detects weeds among corn, soybean, and cotton plants. It uses cameras, processors, a carbon-fiber truss-structure boom and a dual product tank. It enables targeted application of non-residual herbicides on weeds within corn, soybean and cotton fields. It can also be used for traditional broadcast application, as well as targeted and traditional spray combined. This strategy reduces crop stress by providing an effective weed-kill strategy, eliminating the chance weeds will rob plants of valuable nutrients and moisture, thus enabling crop roots to thrive. Plus, when using AutoTrac™ technologies, the sprayer will stay between rows and off the crop further reducing potential crop damage.

The dual-tank configuration lets you apply targeted spray and traditional broadcast at the same time, combining two passes in one to save you time and money. Target spray weeds and broadcast fungicide, or better manage weeds by applying a non-residual targeted spray and residual broadcast, all in one pass. Using Targeted Spraying to kill weeds, it can be done at a lower cost by applying only what you need – when and where you need it. Or, with the dual-tank capability of See & Spray Ultimate, use different chemical mixes independently of each other and at different target rates – all on the same pass. Plus, the amount of herbicide saved during Targeted Spraying can be used for a second and third pass during the growing season to address weed control all season long.

MEET SEE & SPRAY ULTIMATE

The cameras and processors are just the beginning. Discover how this See & Spray technology works.

Vision Processing Unit

Multiple processors across the boom use camera vision technology and machine learning to detect weeds from plants, and activate sprayer nozzles all within 200 milliseconds.

Cameras

36 cameras mounted across the boom scan more than 2,100 square feet (195 m2) at once.

Dual Product Solution system

The tank is split in two, with either 1,000 gallons (3,785L) or 1,200 gallons (4,542L) total capacity. Use two independent tank mixes simultaneously with targeted spray and traditional broadcast spray, or a single, combined tank mix for either targeted spray-only or broadcast spray-only.

ExactApply™ Nozzle Control System

Individual nozzle control with ExactApply offers precise droplet sizing for a consistent targeted spray that also reduces over-application and off-target drift.

Carbon-Fiber Truss-Style Boom

The new, 120 ft. (36.6 m) carbon-fiber truss-style boom is lighter than steel, providing the stability needed to enable targeted spray.

BoomTrac™ Ultimate Height Control

BoomTrac Ultimate ensures consistent height control when traveling across uneven fields for precise application, with 25% better spray accuracy* than the next best manufacturer. *Based on Iowa State University testing; scores represent composite data over a variety of terrains at factory-calibrated settings. Performance varies based on user-specified settings and adjustments. BoomTrac Ultimate tested on MY 2023 412R Sprayer with 36.6-m (120-ft) truss-style carbon fiber boom; NORAC installed on MY 2022 John Deere 4 Series Sprayer with 36.6-m (120-ft) steel boom; Raven AutoBoom XRT installed on MY 2022 John Deere 4 Series Sprayer with 36.6-m (120-ft) steel boom. Operated at 12mph and 30-in.

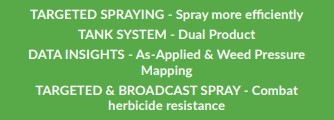

See & Spray™ Ultimate Agronomic Trial: Target Spraying with Dual Product Solution System for Waterhemp in Soybeans at V5 growth stage

Our study was conducted in an Illinois soybean field at the V5 growth stage to target spray for waterhemp in the summer of 2021. Using an enhanced herbicide program consisting of both targeted spray (non-residual) and broadcast (residual) tank mixes, and with higher sensitivity settings to study weed efficacy, See & Spray Ultimate delivered 7% better weed control with 47% less herbicide volume used. These results are made possible by the dual product system, which eliminates in-tank herbicide antagonism that reduces herbicide efficacy. Our agronomic and product experts have and will continue to partner with state universities on additional trials, plus we’ll continue to conduct our own strip trials to ensure our products and technologies help you gain improving yields, cost efficiency, and profitability in your operation.

Questions:

What’s the difference between See & Spray Ultimate and

See & Spray Select?See & Spray Ultimate detects weeds among corn, soybean, and cotton plants. It uses cameras, processors, a carbon-fiber truss-structure boom and a dual product tank. It enables targeted application of non-residual herbicides on weeds. It can also be used for traditional broadcast application, as well as targeted and traditional spray combined. See & Spray Select is for use in fallow ground only. It uses a colour-detecting technology to identify and target spray green on brown soil. See & Spray Select can also spray both targeted spray and traditional spray in one pass, with a single tank mix. Reference chart above for features:

Can I add See & Spray Ultimate to my current Sprayer?

No. See & Spray Ultimate is factory installed on new Sprayers only. It is not available as a Performance Upgrade Kit. What model Sprayers is See & Spray Ultimate available on? See & Spray Ultimate is only available on the 410R, 412R and 612R Sprayers.

What boom sizes are available on See & Spray Ultimate?

The 120 ft (36.6 m) carbon-fiber truss-style boom is the only boom size available for See & Spray Ultimate. What are the dual tank split sizes available on See & Spray Ultimate? The 410R Sprayer has a 1,000 gallon (3,785.4 L) tank with a 650/350 gallon (2,460.5/1,324.9 L) split. The 412R and 612R Sprayer have a 1,200 gallon (4,543 L) tank with a 750/450 gallon (2,839.6/1,703.4 L) split.

-

Farmer Focus – John Pawsey

Since my last submission to Direct Driller Farmer Focus was September, I owe you a report on what we have stuck in the ground for harvest 2022 and how it’s looking at the time of writing.

Buoyed up by my harvest 2021 organic oilseed rape crop, I planted a further crop in August but was persuaded that my previous mix of rape, fenugreek and beseem clover was not the way to go and that rape, buckwheat and a more frost intolerant variety of Tabor beseem clover was a more reliable option. Quite why I didn’t ignore that advice given that my previous crop did so well is beyond me, as the new mix offered my oilseed rape to the flea-beetles for breakfast. It pretty much didn’t even manage a true leaf. I visited David White in Little Wilbraham late in the autumn and his flea-beetle free diverse mix of all-and-sundry plus rape looked amazing. The organic grower can only plant companion species that will be taken out by a frost, whereas David can plant a much more diverse mix to confuse said insect and then tickle the unwanted plants up with a light dose of herbicide. David (allthe-tools-in-the-box) White as I affectionately call him.

I should point out at this juncture to save the younger reader from Goggling the word “frost” an explanation. In the 1970s sometimes the temperature would dip below freezing overnight (I know, it seems crazy. We wore real fleece from sheep in those days, not a pretend one made with petrochemicals), and when we woke up in the morning the grass was all white in the garden because the water on the leaves had frozen into beautiful crystals making everything look like fairy land. Also, the ground froze meaning that there was a huge amount of resistance in the soil and so we could take a 20 tonne tractor and a massive cultivator onto our ploughed fields to do some cultivating without damaging the soil. Now kids, Google “oxymoron”.

My failed oilseed rape crop was re-drilled with vetches which looks fantastic.

We planted our usual amount of spelt which I love as it grows so tall by this time of the year it is taller than any of our weeds which makes the farm look amazing from the road. The same applies to Millers Choice heritage wheat which has the same positive visual effect for my farming neighbours. By the way reader, if you are thinking of growing any spelt, the only variety to grow is Zollernspeltz. Don’t be persuaded otherwise by your seeds-person. If they try and tempt you to grow spring spelt, cancel your account with them immediately as they are idiots or ask for an extra gear on your combine harvester which you won’t be able to afford the repayments on.

We have also planted 25 hectares of Wildfarmed Grain for musician turned farmer Andy Cato. Andy came to Shimpling Park Farm last year and annoyingly he was charming, handsome, knowledgeable and extremely tall. He also has a full head of hair which I always hate on a man. I invited him for lunch and I am afraid to say that Alice Pawsey let herself down and her family down by swooning allover the poor chap. It was pathetic. He then broke one of our kitchen chairs by the simple act of sitting on it. I suggested to Alice afterwards that perhaps he was a little fat but she assured me it was muscle built up during the days when he worked his French farm with horses. Said chair is still broken because, “Andy sat on it”. See what I mean?

I had the absolute pleasure of going to Andy’s farm in Coleshill a couple of weeks ago and what he is doing there is truly inspiring and I seriously urge you to go if you ever get the chance. It’s mind blowing. I travelled down to Andy’s farm with Alex and John Cherry of Groundswell fame or as I tell my friends, I rode to Wiltshire with Regenerative Royalty. All our winter wheat this year is a 50/50 mix of Extase and Siskin and all our winter beans have been sown with the same varieties with Vespa as a bicrop. Our harvest 2021 bean/wheat attempt was a little light on beans due to a low germination in the beans of 75%, so when it came to separating them in November last year, we had almost exactly one third beans to two thirds wheat but managed to raise the wheat grain protein by a percent which was encouraging. This year’s bicrop has a much better bean establishment and looking at them today I would imagine that the ratio will be reversed. It will be interesting to see what that increased bean yield has on the quality of the wheat.

I’ve been pestering Josiah Meldrum from Hodmedod’s for a number of years to grow some of their exotic pulses for them. Apart from Josiah also having a full head of hair (see Cato), he is a really nice man to deal with. There are some companies that whenever you work with them growing novel crops, you get the niggling feeling that you have taken all the risk and the price you get in the end from them didn’t really reward you for your labours. I get a warm feeling when talking to Josiah and so we have got a bicrop in the ground of camelina and entils for him. Josiah said that the lentils will use the camelina as architecture to prevent them from going completely flat at harvest time making their August gathering a joy and I believe him. To be honest, even if it doesn’t work, I will forgive him and grow more next year because he is such a lovely man.

Another great man to grow for is Peter Fairs from Fairking. Peter is the man we grew the first crop of organic chia for last year. If you are interested, it was the first crop of organic chia ever grown in the history of chia growing in the whole of the United Kingdom (just saying). It actually did incredibly well, and although it was relatively uncompetitive with weeds initially, we hoed it carefully once and then it grew up like a forest. I think we harvested it late September and Andrew Fairs (it’s a family company), also having a Claas combine, (they have harvested chia on their own farm but it wasn’t organic, hence my above undisputed claim), texted through the ideal settings and we roared through the standing crop with no problems.

I put some hessian down on our ventilated grain store floors (it’s a teeny tiny seed) and piled the chia in about a metre high and blasted it with ambient air for a few days and then sent it off for cleaning. Anyway, we are growing some more for Peter this year in the same field as the camelina/lentil crop. The field in question is on a south facing slope (riotous laughter as I mention slope and Suffolk in the same sentence), so if they come on flower at the same time, the blue flowered chia below the yellow flowered camelina, means I will have sown a massive Ukrainian flag. I will be charging for photos.

We’ve managed to inter-row all of our crops once, which is all we ever do, apart from the spelt (see above) and all the under-sowing of fertility leys has been completed. Although we have had very little rain this spring to date, our crops still seem to be getting some moisture from our clay soils but the shallowly sown small seeded under-sowings could do with soft refreshing rain to get them going.

As you know, we organic farmers do a bit of cultivation to mineralise some of the goodness we have built up in our leys and to deal with some weeds. This year all of my spring sown crops were established after a green manure, grazed by sheep over the winter and then with three light and shallow passes with a cultivator we managed to get our crops in with much less soil disturbance than usual. You’d be proud of me.

-

Agronomist In Focus…

CHRIS MARTIN FROM AGROVISTA

Industrial farming has been an incredible success story when it comes to increasing production. But many people, including me, believe this era is coming to an end. It is time to rethink the way we go about producing crops.

For the past few decades UK agriculture has become increasingly reliant on the can to control grass weeds, diseases and pests, and on heavy machinery to beat soil into submission to create seed-beds. We’ve been fighting mother nature for the past 70 years, and we now need to work with her. The silver bullets we once had to control all manner of ills are not coming along as often and, when they do, they tend to break down more quickly to resistance pressures.

The ongoing degradation of biodiversity and soil fertility we have experienced is making agriculture increasingly reliant on these synthetic inputs to prop up the system. It will get worse and, at some point, it will fail. Putting things right won’t happen overnight. We need to wean ourselves off this industrial approach and adopt a hybrid model that incorporates the best holistic methods backed up by effective chemistry. We need to switch from degenerative to regenerative approaches.

Done correctly, this will result in:

• Better soil health to help optimise crop health and yield

• Maintained or enhanced crop yields to underpin returns and drive down production costs

• Improved farm profitability through targeted inputs and reduced establishment costs

• Enhanced carbon sequestration to tackle climate change and offer potential new income streams.

Regenerative agriculture has shot to prominence over the past couple of years in the UK, but many people are unsure what it entails. I define it as a system of farming principles and practices that aims to reverse the errors created by previous unsustainable methods.

It works alongside nature to increase biodiversity, improve soils and protect the environment, while delivering benefits to humans through an improved natural environment and healthier ecosystems. The journey towards regenerative agriculture can appear very daunting. However, I cannot emphasise enough that it is not prescriptive – how far people want to go down the more sustainable farming route is a personal choice. It doesn’t have to be all or nothing; very useful effects can often be obtained from quite conservative tweaks, depending on the farm’s current practices, and the process can be undertaken at a pace that suits the individual.

Some people might opt for a complete reboot, reassessing their system and introducing wholesale change. For others, it may be as simple as dropping a pass with a power harrow, or amending the rotation. There are plenty of stops where you can get off along the way.

Full-blown regenerative agriculture is based on five key

principles:1 Limiting physical and chemical disturbance of the soil

Reduced tillage can bring several advantages, including improved soil structure and stability, increased drainage and water-holding capacity and reduced risk of runoff and pollution of surface waters. It also results in significant savings in energy consumption and lower CO2 emissions.

Options will depend on a range of factors, including regional suitability, soil type and drainage, along with soil biology and chemistry, harvest residue management, resistant grass weeds and plant nutrition.

2 Keeping soil covered

Providing the soil with armour by employing cover and catch crops to maintain plant cover/residues at all times will protect the soil from adverse conditions, greatly reducing wind and water erosion and compaction, whilst preventing moisture evaporation and germination of weed seeds.

3 Keeping living roots in the soil

Ensuring living roots are always present will help improve soil structure and nutrient capture, while reducing soil erosion and building soil fertility and nutrition. Living plants are also essential for harvesting sunlight, our greatest resource.

4 Plant diversity

Increased diversity can be achieved by intercropping cash crops, improving crop rotations and using multi-species cover crops. Growing a range of plants across the farm helps to improve crop resilience and optimise yields over time. A good mix of species will build a healthy soil microbial population and improve soil biodiversity, supplying plants with the nutrients they need, which greatly reduces the need for synthetic fertilisers.

5 Integrating livestock

This practice benefits soil health, animal health and the environment. Grazing animals after annual crop harvests aids in the conversion of high-carbon residues to low-carbon organic manure. Grazing on cover crops can allow more nutrient cycling from crop to soil and carbon sequestration into your soils.

By adopting some or all of the above principles to varying degrees that best fit a farm’s individual circumstances, growers can start to improve the sustainability of their systems, building long-term soil health and functionality whilst maintaining farm yields and improving overall farm profitability. So where do we start? There are several things we need to ascertain before any decisions are made: what is the current soil heath status; what does the grower want to do; how can we enable that vision; how can we ensure progress remains on track?

“The journey towards regenerative agriculture is not prescriptive – how far people want to go is a personal choice”

• What is the current soil heath status?

We must first understand the relationship between a soil’s physical structure, its biology and the chemical processes within it. These are the keys to creating and maintaining healthy soils that are essential for crop and livestock production.

The whole process starts with a comprehensive soil test. If you don’t measure, you can’t manage. You have to know the starting point for the physical, biological and chemical properties of your soils.

• What does the grower want/need to do?

What is the main driver – is it long-term soil health, carbon capture, compliance with support schemes, or improving the legacy of the farm, for example? Where is the farmer in terms of the journey and where does he or she want to go? Most importantly, be realistic. Is the land capable of delivering those aims? And what about the bottom line? The financials are often overlooked. Throughout this process, the farm must still make money. Many people say you have to take a hit in the first few years – buy a direct drill and the benefits will come. I fundamentally disagree – if you are not making money, the process will eventually fail, and you are putting your business at unnecessary risk.

• How can we enable the vision?

We can now decide what action to take, by examining how various farming practices affect soils and what needs to be done to deliver the desired changes. Do we need to rethink the farm’s machinery policy? Is the current rotation suitable to achieve the goals we have set? Do we need to rethink the whole production system?

There is no black-and-white answer – any advice must be tailored to an individual farm’s needs, its ability to deliver, and the timeframe involved, based on the balance of probability of achieving the best outcome.

• How can we ensure progress remains on track?

We need to ensure we are using useful key performance indicators that are, above all, practical. Using definitive numbers may look and sound good, but they are often of limited use. The soil is a living, dynamic medium and I’ve yet to find a soil test that provides a definitive numerical figure that is both meaningful and fully repeatable. We need to be looking for trends to ensure we are going in the right direction, whether that be financial or physical. There is no blueprint for success. We need to bridge the gap between the science and practical farming, and a degree of flexibility will be key.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

HIGH HOPES FOR HARVEST

With crops on the farm showing great promise, output prices at record levels and the family’s agricultural machinery business operating at capacity, Suffolk arable farmer and inventor of the Opti-Till® direct strip seeding system Jeff Claydon is optimistic for the months ahead. But it is tinged with caution, the watchword in today’s topsy turvy world.

25.05.2022

Whilst drafting my last article for Direct Driller, Russia had just invaded Ukraine, provoking military conflict and war in the country. Almost three months later, the catastrophe and humanitarian crisis continue with thousands killed, homes and cities destroyed along with millions displaced and seeking refuge. Global supply shortages have caused sky-rocketing prices with far-reaching and dramatic impacts. In the agricultural sector, global uncertainties and a tightening of exportable surpluses have pushed combinable crop prices to previously unheard-of levels, with wheat currently trading at north of £300/t and oilseed rape over £800/t. Whilst this will benefit the arable sector, those in the livestock and poultry sectors are struggling.

Higher prices are quickly being reflected in the cost of food in the shops and if there is any positive to come out of the current situation it will be to make consumers reassess the importance of farming and what they eat. Back in the 1970s food accounted for a substantial proportion of a typical family’s budget, but over the years governments of all persuasion have prioritised cheap food and it has fallen down the list of most people’s’ priorities. For decades, the public has given little thought to food security, where it comes from or how it is produced; perhaps this will provide a wake-up call and encourage them to focus on the things in life which really matter.

Global agricultural production is forecasted to need to increase 60 per cent by 2050 just to keep pace with population growth. But, even as governments around the world stress the need for farmers to produce more, the legislation which they and other bureaucrats devise and sanction is restricting our access to inputs and stifling yield growth. During the last decade production has plateaued and the current UK five-year average wheat yield is just 8.3t/ha, so something has to give.

A busy time

So much has happened here during the last three months that it is difficult to know where to start. Having just looked around the building site outside my office which will shortly form the new production and assembly area of the Claydon factory that is a good place to start.

With demand for Claydon products at record levels and our order books full for months ahead, I am delighted to see work on the new building progressing apace. Just this morning, for example, the four 3.2t gantry cranes which will move components and completed machines around the factory were delivered and installed. Measuring 36m x 36m, the clear-span building will add 1300m2 to our factory space and double production capacity. The plan is for it to come on stream in the summer, but we will announce that nearer the time. In the meantime, I would like to thank all our customers for their continued support and enthusiasm for the Claydon Opti-Till® System which has helped to generate additional customers and created the need for the new building.

Invest in the future

With production costs skyrocketing and inflation at its highest level for more than four decades, farmers are looking to reduce costs whilst maintaining or increasing production. Rather than squandering any windfall from higher prices by continuing to operate inefficiently, forward thinking businesses recognise the need to invest in equipment and techniques which produce lasting benefits to help secure their future, so interest in Opti-Till® is increasing.

The was confirmed at the start of the week when I and my team welcomed representatives from our distributors in Denmark and Germany who brought with them 25 existing and potential customers to see Claydon products being manufactured and tour our farm. This visit follows a series of visits by our importers and customers from Lithuania, Romania, and Poland. It was organised by Simon Revell, our Export Manager, and was at an ideal time of the year for visitors to see how well Claydon-drilled crops are looking.

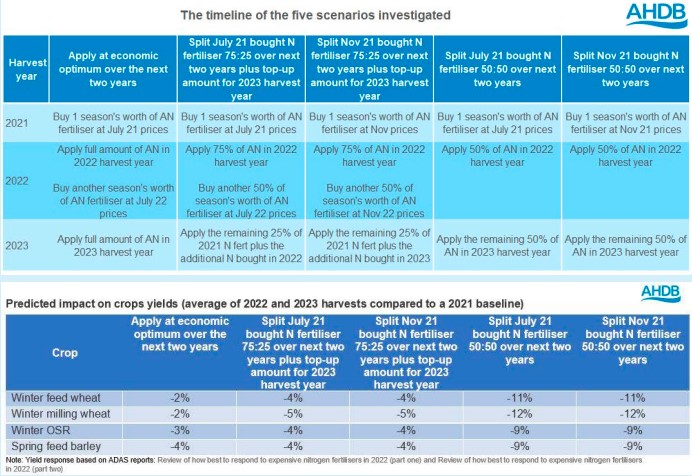

As part of my presentation, I showed our guests a slide based on information produced by Harry Henderson, AHDB’s Knowledge Exchange Manager – Cereals & Oilseeds, showing the cost of establishing winter wheat on 20 AHDB Monitor farms and the yields achieved by various approaches. Farm 12, with one of the highest yields of milling wheat but lowest establishment costs, was Rick Davies, a long-standing Claydon customer, who invested in a 3m Claydon Hybrid drill (upgrading to a 4.8m Hybrid in 2015) and a 7.5m Straw Harrow in 2010. Costs will have increased considerably since this data was produced but the proportional costs are really telling the story. When discussing his reasons for switching to the Claydon System in an article published in Crop Production Magazine during 2015 he summed up a number of points so well that I have quoted him in the paragraph below.

“It is no exaggeration to say that the Claydon System has transformed the way we think about farming and how we actually farm. Having used conventional cultivations and become used to seeing perfect-looking seedbeds for so many years, moving to the Claydon System was a huge leap of faith and it took time to get used to the idea that it would look different. But the results prove that you cannot judge a crop by its initial visual appearance and what really counts is how much goes into the combine tank. Now that we have experienced the benefits we continually ask ourselves why we did not consider the move earlier. But had we not done so when we did we would not be in such a strong position today. I am very pleased that we made the transition voluntarily rather than being forced into it by a lack of profitability, as I suspect some will,”

With some customers savings around £250/ha on their establishment costs and enjoying a yield benefit of up to 1.5t/ ha the advantages are obvious. On the Claydon farm our goal is to achieve the highest outputs at the lowest cost, but that does not mean skimping on inputs; far from it in fact. Rather than spending vast amounts on unnecessary tillage we invest in wisely in inputs which enhance and protect the potential value of our farm and crops.

This season all winter sown crops were drilled by midOctober, helped by the fact that Claydon Opti-Till® enables us to establish the crop in 20% of the time, at a fraction of the cost and using 10% of the fuel (<15 l/ha) compared with a plough-based system. High productivity counts for a lot when the weather is catchy, the window of opportunity is limited, and the number of drilling days are limited, while saving fuel has become essential at today’s prices.

A dry start to the year

2022 has brought with it a very mixed bag of weather. Between New Year’s day and today our farm weather station has recorded less than 170mm of rain, much lower than the farm’s long-term average, while April brought more days with overnight frosts than without, slowing the crops’ growth. Despite very little rain since 1 April, they have caught up well, highlighting the benefits of establishing good rooting structures to make best use of the moisture which is in the ground. Whilst driving around the farm this morning I called in at ‘80-acre’, a field which has been managed using the Claydon Opti-Till® System for 20 years and featured in Direct Driller throughout the season. All of it is into LG Skyscraper winter wheat, which despite the lack of rain continues to look very good. To date it has received just 180kgN/ha, plus the T0 and T1 fungicides, but holds great promise.

In the last issue of Direct Driller, I highlighted the importance of drainage and talked about an issue in the corner of that field where a decades-old tile drain had collapsed during the winter, resulting in a significant area becoming waterlogged. I had planned to sort it out after harvest, but the very dry weather allowed local drainage contractor W. R. Suckling & Sons to come in a couple of weeks ago and install new plastic pipes at a depth of 1m. They did an excellent job, and we will cross mole the area in the autumn if conditions allow or go through the following crop of spring oats early next year.

I also called in to check on the progress of our DK Excited hybrid oilseed rape which was drilled within three days of harvesting the previous crop of winter wheat on 15 August. We went directly into chopped straw and stubble using a preproduction version of our new Claydon Evolution drill and a seed rate of just 2.7kg/ha.. Experience has shown that the sooner we can drill oilseed rape behind the combine the better, as the plants are stronger and more able to fend off the Cabbage Stem Flea Beetle. The damp weather and slightly cooler temperatures after drilling, combined with the extra vigour of the hybrid seed, resulted in excellent establishment. Despite having received just 150kgN/ha the crop has developed exceptionally well and looks set to deliver a very high yield at harvest. With rapeseed prices currently around £800/t that would produce a very attractive margin.

This season’s spring oat area is taken up by Lion, a new variety which, according to its breeder Elsoms, combines excellent kernel content and hullability, together with stiff straw and good agronomic package. With seed in short supply, we drilled the crop on 15 March at just 100kg/ha and to date it has only received 50kgN/ha, although another 50kgN/ha will go on shortly taking the total to 100kgN/ha. ‘Lion’, a new variety of spring oats, looks good despite a sowing rate of just 100kg/ha and little rain when this photograph was taken on 18 May.

Even with very little rain since it was drilled the crop looks excellent and last week I went through with a Claydon TerraBlade inter-row hoe to take out grassweeds growing between the band-sown rows before they had a chance to develop and compete with the spring oats. Growing conditions have been much the same as last year when this low input crop achieved over 7t/ha with excellent margins, so I am optimistic that it will produce excellent results.

And finally!

After 44 years’ service the roof at Gaines Hall, our Grade II listed 16th Century farmhouse, is being rethatched, this time with wheat straw supplied by accredited master thatcher Harry Roberts of Harry Roberts Thatching Services. Harry is one of the very few who grows his own straw, enabling him to offer a comprehensive field to roof service and ensuring the quality of materials is as high as it can be. He uses straw from Maris Widgeon, now a heritage variety, which was originally developed in 1964 by the Plant Breeding Institute at Trumpington near Cambridge and has traditionally been used for thatching in the UK.

We chose Harry to do the job because he specifies that his straw crops are drilled with a Claydon drill. When I visited the farm which his brother-in-law Sam Clear owns to see it being produced Harry explained that sowing the crop in bands results in the wheat stems being much thicker, more resilient and of higher quality than those drilled at the conventional spacing. The crop is cut with a binder, stood in stooks for two weeks, then threshed in the traditional way to produce the best quality straw for thatching.

Harry is due to complete the work at Gaines Hall in June, so I am looking forward to seeing the final result. I will include a photograph of the finished product in the next issue of Direct Driller, as well as discussing the harvest and our plans for the season ahead.

-

Farmer Focus – Julian Gold

Following directly on from my January ramblings , I was lucky enough to have a couple of frosty nights in early Feb which allowed me to roll 30 Ha of cover crops with our 10 m roll on the controlled traffic wheelings. I got pretty well 100% kill on everything rolled in the early hours before the temperature climbed above about minus 2. The later areas rolled after daybreak did not fully die back and I had to reroll them on the next (and last!) frost of the season to finish the job off.

After thinking for the last few seasons that I was getting negative effects in spring barley following grazed cover crops it was useful to be able to compare the two scenarios properly.The spring barley on both grazed and ungrazed blocks was from the same batch of seed drilled at the same time and the same seedrate with the dale drill.Establishment was approximately 50-60% in the grazed fields and 70-75% in the ungrazed fields and the crop on the ungrazed block has grown away better . I will be surprised if the yield is not significantly higher ( will report back in due course after harvest )

Going forwards I am now thinking that fields destined for spring barley will be subsoiled straight behind the combine and then immediately sown with frost susceptible cover which will not be grazed and will be direct drilled into good soil conditions after frost/glyphosate destruction. I can hear all the die hard “regen aggers” screaming what about livestock integration but luckily you will all be pleased to hear that I still see a need for livestock integration but maybe grazing winter cereals rather than cover crops. For a number of years we have experimented fencing small areas in Winter Barley fields and mob stocking them sheep for a few days . Results have been favourable in that the crop has had less disease through the season and has ended up shorter at harvest time ( good for us as we plant OSR into chopped Winter Barley straw so don’t want much of it ! )

Unfortunately, the areas involved have never been large enough to get accurate yield data from the combine to see whether yield is affected. This year we have grazed a much bigger area alongside ungrazed in the same field so should be able to get yield data. (NIABTAG were involved in a similar trial grazing wheat and sent leaves away for disease inoculum testing which showed massive reductions in Septoria and yellow rust infection in the grazed areas )

My thinking is that the most appropriate place to use sheep may be in this winter cereal grazing scenario , giving a number of possible benefits : -Reducing disease inoculum -reducing growth regulator use – no detrimental effect on establishment ( like we are seeing in spring barley after grazed covers ) as crop already established before grazing -possibly allows crops to be drilled earlier in September in good soil conditions and then use sheep grazing to obtain benefits of later drilling by removing pretty well all above ground leaf area and hence reduce Septoria and BYDV problems????

I am afraid my penchant for collecting drills is continuing .Following on from my thoughts in my last article we have ordered an Horizon disc drill complete with row cleaners to hopefully prevent the bad hair pinning we have previously experienced when using disc drills.