If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Farmer Focus – Tim Parton

Well, what a roller coaster of a spring, coming out of yet another wet winter. Land here coped superbly, yet again giving me a real feeling of contentment seeing drains flowing with clear water, leaving my nutrients and soil where they should be.

Drilling was a dream this year with crops going in in ideal conditions, with the addition of brewed biology or compost extract. Extraction was a little bit time consuming to start with until I got into a routine (see from the picture). I have extracted the compost by first mixing a slurry in a bucket to release the available fungal spores and bacteria from the compost. This is then put into a top hat filter to take out any large debris. This is then emptied into the drill tank and applied using the peristaltic pumps with no filtration. There is still a lot of debris left in the mixture, which I put down in the seeding trench with the seed.

A filtered system tends to block and is the main reason I switched to peristaltic pumps in order to be able to handle the mixture. Time will tell if applying compost extract is needed on my soil or not (I will keep you posted). I try to farm using biology and nutrition to keep my carbon footprint low giving me more carbon to sell, as in my opinion we can all be sequestering a lot of carbon with cover crops etc, but if your footprint is still high you could easily be in a position of having very little to sell; something which we will all have to be aware of moving forward as I see carbon being a big income for us when subsidies disappear altogether.

Using the Bio-meter to monitor change ( I do not believe it to be 100% accurate like most monitors), I have been getting results of 1:6:1 fungi to bacteria, which shows what I am doing is working. I firmly believe replacing fungicides with biology has played a big part in my quest for a more fungal dominated soil. This also helps the plant’s immune system to work better in fighting off disease/pest attacks, but also gives it (the plant), the required nutrition to give the best achievable yield within the growing year. I do not class myself as a low input farmer; I class what I and other farmers are doing as intelligent farming, since we are making decisions to obtain the best yields but with a lower input cost, where I would still be prepared to pay for more expensive inputs if deemed necessary to obtain that high profit. So far, I have found that by keeping nutrition balanced and using biology to replace fungicides I can achieve the desired effect whilst still improving my soil. I feel we, as society, cannot keep destroying the planet in the name of food production, when we are proving it can be done while regenerating the planet.

This year working again with Mike and Nick from Edaphos, I am growing wheat with no soil applied nitrogen, along with Spring Barley and Oilseed Rape which have had 21kg/ha of soil applied nitrogen. These crops have then been monitored using a chlorophyll meter along with sap/tissue test, with Foliar applied nitrogen being used to make up short falls. This also allows me to keep the plant totally balanced through the growing season as a plant’s limitation is always its lowest deficiency in my opinion. At the time of writing this article I have not used any fungicides and hope to get through the season without them, as I have read many papers about the loss of aggregation within soil where they have been used. In addition, the breakdown of debris is faster in my experience due to the barrier of fungicides not being present.

A new addition to the farm is my Crimper roller made yet again from Trevor Tappin which should be on show at Groundswell. This I hope will allow me to push yet further away from herbicides in the years when I have no frosty nights (3am start) to be able to roll with a Cambridge roll to destroy the cover crops. I like to drill on the green where possible as well, but the one crop where I have always had problems (or yield reductions) is Spring Barley, where I like to destroy the cover crop at least three weeks before drilling. This year I left a little patch (GPS failed to engage on the sprayer) where I drilled on the green and sprayed post drilling. You can see from the picture the effects this has on the crop. So even though the sprayer had let me down there is always a positive to be found in every situation.

On the flip side of drilling on the green where I drilled spring beans on the green and had good cover, it was the only place on the farm where moisture could still be found on the farm during April. If we were to continue to have these dry Springs crimping would definitely be the way forward to retain moisture.

I wish everybody an enjoyable bumper Harvest

-

Comparing Infiltration Rates In Soils Managed With Conventional And Alternative Farming Methods: A Meta-Analysis

Written by Andrea D. Basche and Marcia S. DeLonge, published: September 19, 2019. Republished under original Copyright

There is a need to develop more resilient, multifunctional agricultural systems, particularly given risks posed by climate change to farm productivity and environmental outcomes [1–3]. Specifically, water-related risks from increased rainfall variability include soil erosion and water pollution, degradation of soil quality, and reductions to crop yields [4–6]. Although soils are vulnerable to water-related risks, they are also being recognized as a medium to mitigate such risk when managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem benefits, beyond maximizing crop production [7,8]. Thus, designing agricultural systems that improve soils and soil water cycling is one strategy that could help reduce negative impacts of increasing rainfall variability [9–12]. To this point, global modelling analyses indicate that enhancing soil water storage at a large scale can benefit crop productivity and improve ecosystem services, such as by reducing runoff [13,14]. However, there is a need to identify how to secure such outcomes on

the farm-scale, particularly across a range of management practices, environments, and climates.Emerging interest in how soils can support climate adaptation has increased the urgency to understand the potential benefits of farms shifting from conventional to alternative agricultural practices. Presently, conventional cropping systems typically feature annual crops, leave the soil bare when a cash crop is not growing, have limited crop diversity, and include regular soil disturbance through tillage: within the United States, only approximately 3% of cropland acres are growing a cover crop and 25% are utilizing no-till practices [15–17]. Soil disturbance, a lack of soil cover and limited plant diversity can degrade soils, reducing their ability to withstand rainfall variability through affects such as disrupting aggregation, increasing bulk density, and limiting water holding capacity [18]. In contrast, management practices such as no-till and cover crops may improve soil properties related to water storage such as aggregate stability and bulk density, but they remain in the minority [19]. The limited adoption rates may be in part related to the fact that, in spite of decades of agronomic research surrounding such practices, we are only beginning to understand their potential value for improving key functions related to soil health and water cycling [18].

A growing body of research suggests that a range of alternative farming practices can contribute to biological, physical and chemical transformations in soil that in turn can increase water storage, improving resilience to droughts, floods, and extreme weather conditions [20,21]. For example, studies have shown that no-till, cover crops and crop rotations can in some cases improve soil carbon content, soil biological activity, and soil physical properties associated with water storage [22–27]. For example, no-till avoids disrupting soil aggregates and structure, and cover crops protect soils, particularly during extreme events. There is also evidence that practices such as introducing perennials and designing diversified landscapes, such as through crop rotations or integrating crop and livestock practices, can improve soils in similar ways, likely by providing vegetative protection of soils above- and belowground, and including living roots throughout the year [28–31]. However, because there are a number of different soil water measurements, the effects of specific practices on soil water properties have not previously been well summarized quantitatively [20].

The primary goal of this analysis was to synthesize published field-experiments investigating impacts of agricultural practices on water infiltration rates and to gain insight into mechanisms impacting infiltration rates. We focused on soil infiltration rates because infiltration is a critical ecosystem function that can mitigate drought and flood risk by facilitating water entry into the soil and reducing water losses by runoff [29]. This is a particularly important ecosystem function given predicted climate changes, especially the trend toward increasing rainfall variability, leading to heavier intensity rainfall events and impacts in non-irrigated agricultural regions when there are longer periods without rainfall [4]. Infiltration rates are frequently measured in field experiments and are sensitive to changes in management. Infiltration rates are also closely related to other important characteristics of soils, including physical aspects such as aggregate stability, bulk density, plant available water, as well as chemical and biological aspects including soil carbon, and microbial biomass [20,26,27].

In this study, we considered a range of specific alternative practices that can be adopted on farms, including notill, cover crops, crop rotations, introducing perennials, and livestock grazing on croplands, compared to more conventional controls (experiments with tillage, no cover crops, monocropping, annual crops, and no grazing). We hypothesized that the various alternative practices would increase infiltration rates, but that the relative impacts would vary, and that is the motivation behind including multiple practices in our analysis. We secondarily explored patterns of additional environmental and management factors (e.g. soil texture, climate indices, and the length of the experiment) that we hypothesized could be modulating observed effects.

Methods

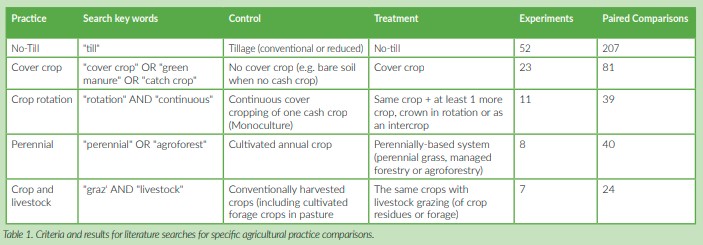

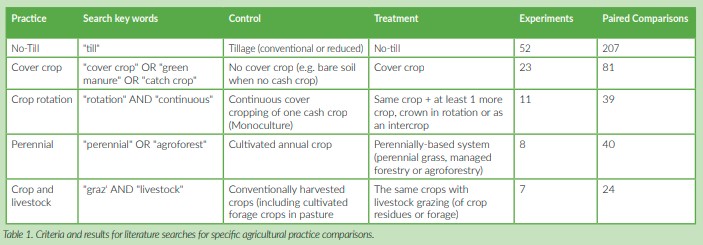

Study criteriaWe evaluated the effects of various alternative farming practices that can be adopted in otherwise conventional farming systems [32–34]. We considered zero tillage (notill) as compared to conventional tillage, cover cropping or green manure practices that keep soils covered compared to leaving them bare (cover crops), diversified farming (crop rotations, intercropping) as compared to monoculture cropping (crop rotations), agricultural systems with mainly perennial compared to annual crop systems (perennials), and grazing of croplands versus conventionally harvested or hayed fields (crop and livestock) (Figs 1 and 2 and Table 1). The main criteria for inclusion were field experiments that:

1. Measured and reported steady-state infiltration rates, defined as the volume of water entering the soil over a designated period;

2. Compared one of the alternative practices of interest relative to select conventional controls in a standardized way.

Literature search

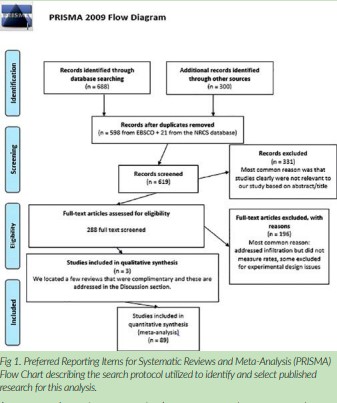

The literature search was conducted using EBSCO Discovery ServiceTM (detailed in Basche and DeLonge [25]) and only included field experiments in English language peer-reviewed literature through 2015 (the earliest publication that met our criteria was from 1978). Keyword strings included “infiltration W1 rate” AND “crop*” for all searches, and additional keywords were used for individual practices (Table 1). These searches returned approximately 700 studies, of which 79 fit our criteria. We used the USDA-NRCS Soil Health Literature database [35] to find additional papers, leading to 10 more studies for a total of 89 (Table 1). Information about article rejection can be found in the PRISMA chart in Fig 1. Articles were rejected because they either did not compare controls to treatments appropriately, did not measure infiltration rate, or were otherwise not relevant to our analysis. For additional details, see the Supporting Information.

Management practices

Experiments within each practice were systematically included in the database only if they fit the below additional criteria.

No till: Papers identified from the additional search term “till*” were included if experiments clearly included a notill treatment. We compared any tillage practices–reduced tillage as well as more physically disruptive tillage practices that are typically described as conventional tillage–to zero tillage as the alternative treatment (unlike some metaanalyses that have compared reduced to conventional tillage separately e.g. van Kessel et al. [36]). When papers included multiple different tillage practices that could have been counted as a control treatment, they were further classified as conventional or reduced tillage, based on reported equipment and/or method of plowing.

Cover crops: Papers identified from the additional search string of “cover crop*” OR “green manure” OR “catch crop*” were included when a control treatment with no cover crop was present (e.g. bare soil when the cash crop was not growing). Experiments were included when the cover crop was grown intentionally to protect the soil and was not harvested, and residues were mechanically terminated, chemically terminated, or left as a green manure (e.g. a crop grown specifically for fertility purposes).

Crop rotation: Papers identified from the additional search string of “rotation” AND “continuous” were included when there was a control treatment that represented the continuous (year after year) cropping of one cash crop. The experimental treatment needed to include the same crop as well as at least one additional crop, grown in rotation (as in McDaniel et al. [23]). We included two experiments where an additional crop was grown not in rotation but as an intercrop (i.e. two plant species grown simultaneously on the same field) and one experiment that met the rotation criteria but was different in that it also included grazing in the experiment treatment but not the control (Table A in S1 File). In all experiments, we recorded the number of crops in rotation for analysis.

Perennials: Papers identified from the additional search string of “perennial” OR “agroforest*” included experiments where a perennial treatment was compared to an annual cropping system. This practice represented more significant shifts in management practices that have been the subject of fewer studies, thus we included control practices that varied slightly (for example, they included monocultures with or without conventional tillage). Treatments included perennial grasses, agroforestry and managed forestry (Table A in S1 File). While these treatments have differences in species and management, they share the critical feature of continuous living cover through perennials. Given the limited number of total studies, we aggregated these into a single class (as in Basche and DeLonge 2017 [25]). Two of the eight experiments ultimately included in this practice also had livestock grazing as part of the treatment (compared to an annual crop system with no livestock; Table A in S1 File).

Crop and livestock: Papers identified from the additional search string of “graz*” AND “livestock” were included if there was a crop-only control and a treatment with a similar crop system that also included livestock grazing. This treatment was of interest as it is representative of one phase of integrated crop-livestock systems that has implications for diversifying cropland management. The identified studies included experiments with either annual crop or pasture-based systems, where control systems were harvested conventionally (i.e. with equipment) whereas treatments included livestock grazing and no conventional harvesting.

Database design

Data from experiments were extracted and categorized systematically. When experiments reported measurements from several years, years were included separately. When experiments included multiple measurements of infiltration rate within a year, measurements were averaged, as has been done in other meta-analysis evaluating soil properties that may be measured on a sub-annual basis [23]. This approach, which was used for 10 studies (and 11% of the response ratios in the database), allowed us to use as much data as possible to capture the influence of the treatments on infiltration rates over a longer timeframe.

We analyzed additional variables to examine how effects of management on infiltration rate are modulated by other factors of interest [23,37,38]. These variables included soil texture (percent sand, silt, clay), climate, study location, and study length. We also analyzed additional information within select practices, including tillage descriptions (within no-till), inclusion of cover crops (within no-till), the number of crops grown in an experiment (within crop rotations), and if crop residues were removed or maintained (within cover crops). Study length was defined as the number of years a treatment was in place, as reported by the authors, and we assumed that this duration explains differences between control and treatment conditions.

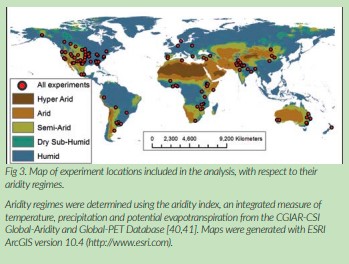

We supplemented our dataset using publicly available sources to explore broader patterns that could be influencing the effectiveness of management practices. When annual precipitation was not reported, we used the Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN)-Daily database [39] (contains records from over 80,000 stations in 180 countries and territories). As an additional indicator of longer-term climate conditions for all study sites, we used locations to extract estimates for the aridity index, an integrated measure of temperature, precipitation and potential evapotranspiration (CGIAR-CSI Global-Aridity and Global-PET Database, resolution of 30 arc seconds [40,41]). In cases where soil textures were not reported in papers from the U.S. (which represented the largest number of studies, Table 1), we used data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Web Soil Survey [42].

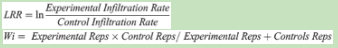

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted by calculating response ratios, representing a comparison of control treatments to experimental treatments, as is common in meta-analysis methodology43. Response ratios (LRR) represented the natural log of the infiltration rate measured in the experimental treatment divided by the infiltration rate measured in the control treatment (Eq 1) [43]. A weighting factor (Wi) was included in the statistical model as is suggested by Phillibert et al. [44] based on the experimental and control replications (Reps) of each study (Eq 2) [45]. Natural log results were back transformed to a percent change to ease interpretation. Results were considered significant if the 95% confidence intervals did not cross zero.

For statistical analyses, the five practices were analyzed separately because there were notable differences in experimental designs and control treatments. A linear mixed model (lme4 package in R) was used to calculate means and standard errors for the five practices. The statistical model also included a random effect of study to account for the factor of similar environments and locations in the cases where experimental designs allowed for multiple paired observations (e.g. a single study included multiple tillage practices or multiple cover crop treatments using different species) [46]. For the two practices that included the largest number of studies (no-till and cover crops) and could therefore be statistically evaluated in greater detail, additional fixed effects including mean annual precipitation, study length and soil texture, were analyzed with a similar linear mixed model [47].

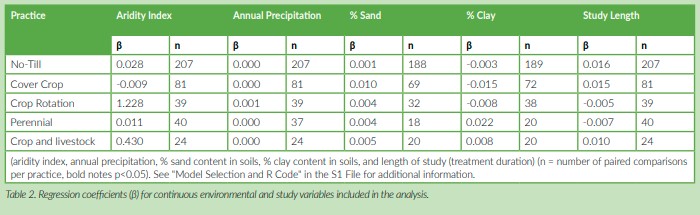

Given the limited sample sizes for the other three practices (perennials, cropland grazing and crop rotations) additional fixed effects models could not be robustly applied, but figures were developed to explore trends (Figs A-C in S1 File). Regression coefficients were calculated to determine the effect of continuous environmental variables (Table 2). Additional details, including sample R code, are provided in the Supporting Information.

A sensitivity analysis was performed for each of the practices using a Jacknife technique, where individual experiments were removed from the respective databases and overall means were recalculated, to determine how sensitive overall effects were to individual experiments44. This technique provides understanding of how the results would change if individual studies were not included in the database. We evaluated histograms for all practices to determine if there was evidence of publication bias (a preference for published studies with significant effects) [48].

Results

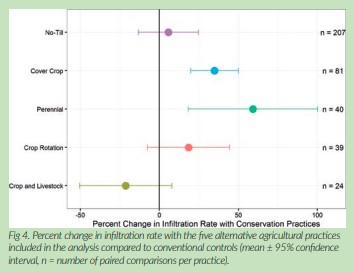

Database descriptionThrough the methodical keyword-based literature search, we identified 89 studies eligible for inclusion in our database, representing 391 paired comparisons on six continents (Fig 3 and Fig D in the S1 File). Many experiments were in North America (31) or Asia (27), with most located in the United States (25) and India (20). More than half of the experiments and subsequent paired comparisons were no-till (207 paired comparisons from 52 studies), while the next largest practice was cover crops (81 paired comparisons from 23 studies). Sixty-three percent of the database (246/391 paired comparisons) demonstrated an increase in infiltration rate with any of the five alternative agricultural practices included in the analysis. Overall means for perennials and cover crops were significantly greater than zero (Fig 4).

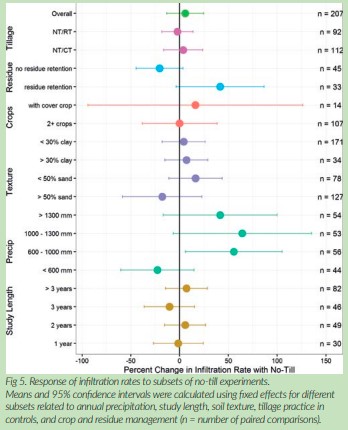

No-Till

The overall mean increase in infiltration rates in no-till versus tillage comparisons was not significantly different from zero (5.7%, confidence interval -13.3–24.7%) (Fig 4). Also, we did not find differences between experiments comparing reduced tillage to no-till versus conventional tillage to notill. We found the effects of no-till to be complex, revealing possible conditions and environments where no-till practices are more likely to increase infiltration rates (Fig 5). For example, in the subset of experiments reporting residue management details (11 with residue retained, 7 with residue removed), there were higher increases in infiltration rates in experiments that combined no-till with residue retention practices (41.5%, confidence interval -3.4–86.6%). Only 2 of 52 experiments reported data capturing the effect of no-till plus a cover crop (compared to tillage plus a cover crop) and results were inconclusive (16.2%, confidence interval -94.0–126.5%). Similarly, there was no significant difference when no-till experiments included more crop diversity (in both control and experimental treatments), such as having at least two crops in rotation or double cropping (0.0%, confidence interval -18.9–18.8%).

With respect to environmental variables, we found an effect of precipitation, with significant improvements in regions with 600 to 1000-mm annual precipitation (55.6%, confidence interval 5.8–105.3%) (Fig 5). There were also greater numbers of results where no-till reduced infiltration rates located in more arid environments (i.e., lower aridity indices), but the effect was not statistically significant (Table 2 and Fig E in the S1 File). We did not detect any clear effects of soil texture, nor did we find differences due to study length (Table 2 and Figs F-G in the S1 File).

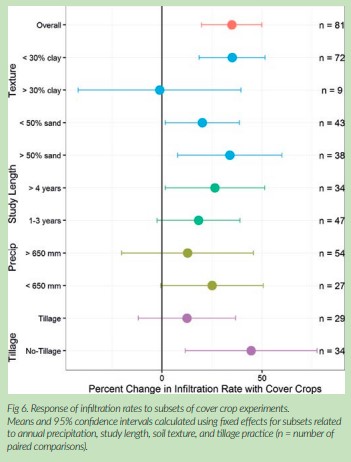

Cover crops

The mean increase in infiltration rates for cover crop experiments (n = 81, 23 studies) was significantly above zero (34.8%, confidence interval 19.8–50.0%) and results demonstrated a few other important differences relative to patterns observed in no-till experiments. For example, there was a significant improvement in infiltration rates when cover crop experiments were in place for more than four years (30.0%, confidence interval 1.7–51.3%, representing 34 of the 71 comparisons) (Fig 6). Also, we did not detect differences when cover crop experiments were aggregated by annual rainfall or aridity index (Fig 6 and Table 2). There was evidence that the effects of cover crops on infiltration rate improvements were greater in coarsely textured soils with higher sand contents and less clay (Table 2 and Fig F in the S1 File). Similar to the notill plus residue retention experiments, we found there to be a significant increase in infiltration rates when experiments combined cover crops with no-till (compared to no cover crops with no-till; 44.6%, confidence interval 11.6–77.5%) (Fig 6).

Crop rotations

Impacts of crop rotations on infiltration rates were inconsistent, with an overall mean effect that was not significantly different from zero (18.5%, confidence interval -7.4–44.4%, n = 39 from 11 experiments) (Fig 4). Many experiments in our database compared monoculture to two crops in rotation, and only a few compared three or more crops in rotation. Further, in many experiments the control crop was monoculture maize (Fig A in the S1 File). The aridity index analysis revealed that most of the declines in infiltration rate among the crop rotation experiments fell within more arid regions (Table 2 and Fig E in the S1 File).

Perennials

Experiments comparing perennial treatments to annual crops showed the largest improvement in infiltration rates (59.2%, confidence interval 18.2–100.2%, n = 40 from 8 experiments) (Fig 4). These experiments included three types of perennial systems: agroforestry, perennial grasses, and managed forestry (Fig B in the S1 File); they were aggregated into a single group for this analysis because of the limited number of available studies (only eight total met the inclusion criteria) and because they share a key feature of continuous roots in the soil (Table A in the S1 File). Despite differences among and between these practices, the perennial practices showed a consistent pattern in that growing perennial rather than annual plants led to improved infiltration rates.

Crop and livestock (cropland grazing)

Experiments that fit our criteria for crop and livestock systems were more likely to contribute to a decline in infiltration rates overall (-21.3%, confidence interval -50.4–7.9%, n = 24 from 7 experiments) (Fig 4). However, individual studies within this practice suggested that pasture-based and diversified annual crop systems with livestock could lead to improved infiltration rates under some conditions (Fig C in the S1 File).

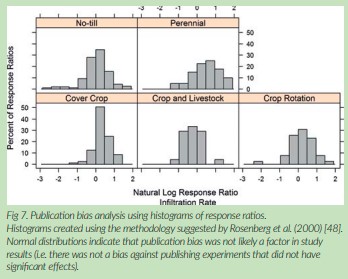

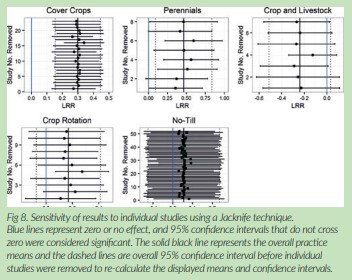

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

We did not find evidence of publication bias in our overall analysis, as shown by histograms demonstrating that experimental results within each practice were not skewed toward very positive or very negative effects (Fig 7). Also, the Jacknife sensitivity analysis revealed robust results, with only minor shifts to overall means and confidence intervals when individual experiments were removed (Fig 8). Results were most robust for notill and cover crops, which had the largest numbers of experiments. However, two practices–crop rotation and perennials–were somewhat sensitive to the removal of individual experiments. When two of the eight perennial experiments were separately removed, the 95% confidence intervals of response rates shifted to slightly cross zero (Fig 8). These experiments were the two with livestock, which suggests that in these environments the presence of livestock did not reduce infiltration [49,50]. For the crop rotation studies, the removal of one experiment [51] led to a significantly different mean from zero.

Discussion

Alternative management impacts infiltration, likely

through biological, chemical and physical processes

Overall we found that the largest infiltration rate changes were associated with practices that entail a continuous presence of roots and soil cover, suggested by the positive improvements of perennial systems compared to annual crops and cover crops compared to no cover crops, as well as the negative trend associated with the crop and livestock systems compared to crop systems only. Determining the exact processes underpinning the observed results is outside the scope of metaanalysis. However, these results point to changes in soil hydrologic function which, in turn, is known to be associated to an intertwined set of biological, chemical and physical factors. For example, physical processes associated with root growth and decomposition contribute to improved soil structure such as porosity and aggregation, which enhances water entry into the soil [52].

Recently, Basche and DeLonge [25] found that cover crops, perennial grasses and agroforestry practices led to significant improvements in two soil hydrological properties related to water infiltration (porosity and water retained at field capacity), which could help explain the effects from those practices in this analysis. The reduced infiltration rates that we found with respect to the crop and livestock studies could be related to the removal of vegetative cover or soil compaction from grazing, although the available studies for this practice were limited [53–55]. Overall, our results suggest that management has an important contribution to infiltration rates, and that these are likely related to soil physical changes.

Given established relationships between soil carbon and soil water properties [26,27], one factor that likely has a role in our findings is the impact of carbon accrual from the analyzed practices. For example, increases in soil carbon have been quantified by meta-analyses in response to cover crops, crop rotations, and other conservation practices [7,23,24]. Also, perennial systems typically store more soil carbon than annual croplands [56–58]. However, reviews evaluating the effect of no-till on carbon have found mixed results [22,59–62], similar to the complex no-till findings in the present analysis. Specifically, these reviews have found that no-till can lead to carbon accrual in some instances but may also lead to no net increase in carbon but rather a redistribution of carbon closer to the soil surface [59]. Further, it has recently been demonstrated that the relationship of soil carbon to soil available water may not be as strong as indicated by prior analyses [63].

Continuous cover of the soil combined with reduced soil disturbance is known to promote enhanced biological activity, with is also linked to physical soil structure. For example, management practices leading to a greater number of earthworms could contribute to soil aggregation and pore creation, increasing water entry [64,65]. A recent meta-analysis found that reduced tillage increased earthworm abundance and biomass by more than 100% compared to conventional inversion tillage [66], suggesting a potential biological mechanism that may help explain the success of no-till in improving infiltration rates under some circumstances.

Cover crops have also been found to increase earthworm populations and recent work finds that they also significantly increased microbial biomass as well as mycorrhizae colonization across a range of experiments [67–69]. Increased biological indicators such as earthworms, microbial communities, microbial biomass and/or mycorrhiza colonization might also be expected in other practices that promote crop diversity and year-round growth, such as crop rotations and perennial systems, potentially facilitating higher infiltration rates through their effects on soil structure as well.

While increasing infiltration rates may mostly be considered important for reducing flooding risk, the previously discussed soil improvements can play a role in reducing the impacts of drought. A recent global meta-analysis found significant improvements from conservation tillage on soil hydrological properties such as aggregate stability, aggregate size, saturated hydraulic conductivity and available water capacity [70]. In particular, increasing available water holding capacity and soil organic matter are understood to increase the likelihood that water will be stored and/ or utilized when drier conditions or drought arise [18].

Further, there is growing evidence that increases in soil organic matter and available water holding capacity are associated with increased yield stability, in particular through increased use of conservation agriculture systems [71,72]. Although tradeoffs may arise between alternative management and crop yields, the results of this work and prior work suggest that they can also improve the soil while increasing yield stability, important benefits to consider in the context of rainfall variability and climate change.

Comparing the efficacy of different management

practicesOur results suggest similarities and distinctions between alternative management that are in many ways corroborated with past studies that have limited their scope to a narrower range of practices. For example, the overall finding that continuous soil cover can improve infiltration rate is corroborated by prior research focused on cover crops or agroforestry. A recent meta-analysis of eight experiments in Argentina found a similar effect of cover crops on infiltration rate, where infiltration was increased by an average of 36% due to the presence of cover crops compared to no cover controls [73]. Also, Ilstedt et al. [74] found that afforestation and agroforestry increased infiltration rates relative to annual crop systems by 100–400% across four experiments in tropical agroecosystems.

Somewhat contrary to conventional thinking around no-till, our global meta-analysis found that no-till did not consistently improve infiltration rates at this scale. In contrast to our findings, a recent qualitative review (mostly from studies within the United States, in both wetter and drier environments) found that notill in most instances increased infiltration rates over conventional tillage [37]. Also, a review of experiments in the Argentine Pampas, a humid environment with well-drained soils, found that no-till doubled infiltration rates [38]. While our results did demonstrate a trend toward improvement, our database included very few cases where infiltration rates increased by at least a factor of two as a result of no-till, even in humid environments (16/207 paired comparisons; Table A in the S1 File).

Also, we did not find a significant effect of no-till in the subset of no-till experiments including cover crops (Fig 5), contrary to our findings in for cover crops (where cover crops increased infiltration rates within the subset of cover crop studies with no-till, Fig 6). This inconsistency may be related to the limited number of no-till experiments reporting infiltration rates for combinations of factors, such as use of cover crops, which would have allowed more comprehensive analysis. We did, however, find that notill experiments with residue retention were more likely to increase infiltration rates, suggesting the importance of combinations of practices to maximize benefits.

Crop rotations had an inconsistent effect on infiltration rates. We did observe a negative effect of crop rotations on infiltration rates in drier regions (Table 2; Fig E in the S1 File). However, the studies that met our criteria were largely from more arid regions, so the limited dataset may have inhibited analysis across a sufficiently wide range of aridity regimes in order to detect stronger overall effects. In a meta-analysis that similarly considered conventional management versus crop rotations but focused on soil carbon, McDaniel et al. [23] found that crop rotations generally increased carbon, but that greater increases were correlated with more precipitation.

Thus, the study revealed a sensitivity of crop rotation impacts to climate, potentially related to small decreases in bulk density that may have affected soil hydrologic function [23]. Together, these findings suggest a need to closely monitor the impacts of crop rotations on several soil variables, especially in drier environments. This may be especially important for this practice, as there is already great deal of variability in the crop diversity and level of complexity of crop rotation practices.

Although limited experiments fit our criteria for crop and livestock systems, the overall result suggests that careful management of these complex systems may be necessary to maintain or increase infiltration rates. While the mean change in infiltration rates was negative across all studies, individual experiments suggested that a positive effect was possible under some circumstances and management practices. For example, Masri and Ryan [75] found infiltration rates increased when a diverse annual crop rotation included livestock as compared to when the systems included crops only. Franzluebbers et al. [76] reported increased infiltration rates in pasture-based systems with versus without livestock, but only when a lower grazing intensity was utilized. It is also important to note that cropland grazing typically represents only one component of a diversified farming system that may have different outcomes when assessed on a larger scale [77].

Uncertainty surrounding measurement timing and

experiment durationOne variable potentially affecting our results could be related to a sensitivity to the timing of measurements in these experiments. This sensitivity may be particularly relevant for the no-till studies. For example, immediately after a tillage event, the infiltration rate in tilled fields could increase relative to no-till because of managed decreases in bulk density [37]. An experiment included in this analysis [78] found greater seasonal differences versus treatment differences when comparing tillage practices to no-till. Our database could not be categorized according to inter-season periods of measurement and management, as such analysis would have been complicated by inconsistent data availability and was beyond the scope of our study. As such, we were only able to evaluate overall trends based on available data and these limitations likely account for some uncertainty in our analysis.

Another related variable that could be introducing uncertainty is the lack of studies reporting effects following a wide range of treatment durations. In our analysis, we did not find experimental length to be a significant factor in our analysis across any of the practices (Table 2; Fig G in the S1 File). This finding therefore does not support the common convention that management practices need be in place for an extended period of time in order to demonstrate improvements to various soil properties. Instead, we found that even after a short period (as little as within the first few years) it was possible for infiltration rates to increase relative to conventional controls in some cases (for example, for some crop rotation and perennial experiments, Fig G in the S1 File). At the same time, longer experiments did not consistently lead to more significant changes. This finding could also be related to the interannual timing of measurements, as infiltration rate is a dynamic process subject to interseason and/or interannual variability. However, examining such effects was beyond the scope of this analysis, as the primary goal was to detect infiltration rate changes between different farming practices.

Uncertainty surrounding data limitations and research

gapsOverall, our results revealed the varying relative abundance of experiments evaluating different practices; no-till experiments comprised more than half of our database, while many fewer experiments evaluated practices such as perennials or crop and livestock systems. This observation aligns with recent findings indicating that more complex agroecological research receives relatively limited research funding [79,80]. While we did find several studies for each practice, our sensitivity analysis revealed that the limited number of experiments in some led to more sensitive results. Smaller sample sizes also limited our ability to explore influences of other environmental and management factors (e.g. we were able to comprehensively evaluate the effects of precipitation and soil texture only for notill and cover crop practices).

Additional levels of analysis that also consider the combined and synergistic effects of multiple management practices would also be valuable. For example, it would be interesting to compare the combined effects of no-till, cover crops, and crop rotations (typically combined in conservation agriculture systems) as compared to conventional agricultural systems. However, such analysis was beyond the scope of this study and would be challenging given the very limited number of experiments that combine practices and report results in a sufficiently similar way to directly compare controls and treatments. More complex, wellreplicated, and long-term studies would be needed to enable a similar meta-analysis to the present study, but with this broader scope.

In general, a lack of detail on environmental and management factors was another important gap in our analysis. Gerstner et al. [81] and Eagle et al. [82] proposed criteria that field experiments should include to increase their utility for meta-analyses or synthesis reports, in the fields of agronomy and ecology. These criteria include environmental features, such as soil and climate characteristics, as well as reporting complete factorial results from experiments.

Conclusions

The overall trend quantified by this analysis is the potential for improvements to infiltration rates with various alternative agricultural management practices, with the greatest benefits observed in response to introducing perennials or cover crops. Our findings suggest the importance of the presence of continuous living plant roots and the positive soil transformations that accrue as a result. We found that no-till practices did not consistently increase infiltration rates but were more likely to do so in more humid environments or when combined with residue retention. Another important finding is that some practices have been substantially less studied than others, particularly ones that show some of the greatest promise for facilitating water infiltration such as the use of perennials.

Future work should explore greater opportunities for expanding practices such as perennial integration into agroecosystems to facilitate improvements to water infiltration. Further, more complex, long-term field experiments that evaluate alternative systems rather than individual practices would benefit our understanding of agroecosystem designs for optimal water outcomes. Additional research is also needed to better understand the potential synergies between optimal water outcomes and other ecological benefits at several scales, such as in relation to soil biology, nutrient cycling, and drought and flood impacts. Utilizing alternative practices that increase water infiltration rates offers the opportunity to mitigate effects of extreme weather that are expected to grow more frequent with climate change.

-

Impressive Yields From New Varieties Despite Stop-Start Harvest

Written by Keith Nicholson

Despite catchy August weather that has left many farmers with the usual harvest headaches there have been some notable performances from several new varieties being grown for the first time, including two new winter barley varieties, that have exceeded the current AHDB winter barley yield estimates of 6.8-7.2t/ha reported to date for 2021 harvested crops

Tim Booth, Lincolnshire Farmer

near SwineheadTim grew a crop of Lightning with a yield of just over 8.6t/ha, a new 2-row conventional winter feed barley from breeder Elsoms Seeds. It’s our first-time growing winter barley as historically, its been tricky to fit into our rotation. However, we changed things up last autumn, drilled 17ha and were rewarded with a fantastic looking crop that had no disease issues, all beit in a low-pressure year for this area. Beyond 1 or 2 minor lodging problems due to heavy rains Lightning competed well producing a lot of tillers which smothered the ground very quickly helping to keep our blackgrass at bay. It’s an early maturing type that proved excellent for an early harvest slot as we followed it with oilseed rape drilled on August 2nd.

Although not really tested it has 8s for Rhynchosporium and net blotch and 7s for mildew and brown rust, so the disease package looks potentially very solid” he confirms.

Tony Scarborough, farmer near

GranthamTony grew a first-time crop of winter barley Bolton harvested on August 9th and achieved almost 8t/ha, again well above AHDB national yield estimates for this season. We drilled on October 12th in decent weather. The variety established quickly, competing extremely well. It stood well during the spring, despite some heavy rain that temporarily yellowed the crop, and received a basic fungicide package at T1 with a more robust spray at T2 on May 12th. Bolton looks a good variety for a mixed farm, proving uncomplicated to grow and producing a significant quantity of good quality stiff straw. We grew two winter barleys this season, including Hawking from breeder KWS which did 6.78t/ha, although both varieties were drilled at the same time and received the same inputs package.

The final bushel weight of 63hL on the Bolton was slightly down on our farm average of 65hL, although that seems to be in line with AHDB reports of national averages of 60-64hL for winter barley this year” adds Tony.

John Wilson, Rankeilour Farms

near Cupar in FifeReports on Bolton have also been positive further north where John drilled 17.6ha of the crop on 15th16th of September. Weather conditions at and post drilling were excellent, and the crop was at the 4-5 tiller stage going into winter. A low-pressure disease year was further aided by a cold snap in early spring so, despite not being fully tested, it did cope extremely well with the very heavy rain we caught in May. Harvested in early August the final yield was an impressive 10.56t/ha, ahead of our 5-year farm average. Specific weight was 68hL, again better than expected and excellent for a feed barley.

Although not really examined on its disease resistance this year Bolton was easy to grow, stood well and looks a straightforward robust variety

Tony Bell, farmer near Thirsk

For Tony a first-time crop of the Group 4 hard wheat Astound achieved a yield of almost 10t/ha supporting its credentials as a robust, low stress variety. We drilled 18ha of Astound, split across 2 fields, with the larger field late sown on November 5th following a ‘difficult to harvest’ crop of maize. Despite heavy rain that submerged parts of the crop, it came through and established extremely well once the land had dried, displaying excellent early vigour. We went with Astound based on its high untreated yield and a relatively high treated yield and to achieve nearly 10t/ha following late drilling, just a modest fungicide package and the very challenging weather conditions it endured was a very positive result overall. Grain quality was excellent, and, in better growing conditions with earlier establishment, I feel that it’s a variety capable of challenging the highest yielding winter wheats we’ve grown in recent years.

George Renner, farmer in Leicestershire

Further south George Renner achieved 9.2t/ha on a crop of Group 3 soft wheat Merit, a new variety to the recommended list that can be used for biscuit making, distilling and for export. We eventually drilled during the 4th week of October, later than desired due to adverse weather and, despite not being in a particularly high risk septoria area, we took no chances applying a robust fungicide strategy. The crop stood well and coped well with the weather thrown at it and, whilst I was satisfied with 9.2t/ha, the potential for a much higher yield was lost during a 6 week dry spell in late April and May which was then followed by a dull June. It’s uncomplicated to grow and with premiums available alongside good marketability I would certainly recommend it

Kit Papworth, farmer near North Walsham in

north-east NorfolkWe grew 14ha of Merit as a seed crop this time to get a feel for it, late drilled in the second week of December following sugar beet. As with most late drilled crops it was slow to emerge before racing through its growth stages the following spring. Tillering nicely, the crop received a robust fungicide programme to combat significant late yellow rust and septoria outbreaks in late May and we were rewarded with a clean crop that should yield over 9t/ha.

Having budgeted the crop at 8.5t/ha it’s a good overall result, however looking ahead to next year, on better fields and with an earlier drilling slot, I’d hope we’d be able to easily achieve 10t/ha as a commercial crop. Merit offers growers a range of marketing options, we’re too far from a mill, so the attraction for us would be to grow for export, given our close proximity to the deep-water port of Great Yarmouth and Merit’s UKS approval for soft milling export

-

Opportunities In The Forward Thinking World Of Regenerative Farming.

The Gentle Farming system will produce the first carbon offset certificates in the Autumn. The buyers can see a portfolio of local farms or those that reflect their needs. Gentle farming will sell the offsets and begin paying farmers this winter.

Written by Thomas Gent from Gentle Farming

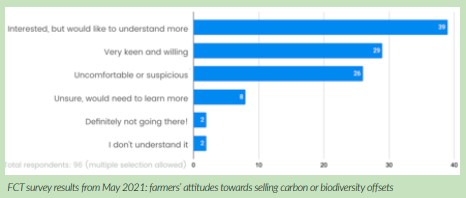

We have had a busy few months moving things forward both in terms of working with farmers and agronomists and also in creating interest from potential companies wanting to invest in their local regenerative farms. We now have over 30 farms subscribed and using the system this harvest to verify their regenerative farming practices and calculate their carbon offset potential. In turn this leads to us being able to produce certified soil carbon offset certificates and to being able to verify these farms are improving their soils and producing food in a carbon friendly way. Free training has been offered to agronomists to build and share knowledge within their industry and so that they can assist their farmers to understand the opportunities within regenerative farming to generate new income streams. Consumers are becoming much more aware of the eco credentials of companies they choose to buy from as well as wanting to connect much more deeply with nature following the COVID pandemic.

This shift in consumer interest is only on the increase with recent reports showing consumers are willing to pay more and actively seek out eco-friendly products. This means there is an increased focus and urgency by businesses into how to deliver this for their customers and meet their own challenging carbon targets. As I speak to corporate sustainability departments and consultants I see that there is a strong demand for local UK based, high quality environmental projects and sources of offsetting that these businesses can invest in.

Gentle farming and its certification partner CommodiCarbon has a methodology that will validate soil carbon offsets taking place on farmland soils and verify the regenerative practices that underpin this soil improvement. The NFU have published their pledges and set their Net zero target goal for 2040. (Only 19 harvests away!) With supermarkets and other industries setting even more ambitious targets we simply do not have the time, action must be taken now. Farming and forestry are among the few industries with potential to sequester more carbon than they are emitting from their activities.

This will require great change which must be supported financially as strong financially viable farms will be in a position to invest in their soils and push the boundaries of new techniques and technology. Carbon offset income streams will contribute to this as will the possibility of increased demand for carbon friendly produce. But carbon is just the start of this new market development. Water and building companies look to improve the local biodiversity of their projects. Regenerative farming can offer a huge range of environmental projects for businesses to support and invest in. The key is to have a structured high quality certification and validation process. Which will be the basis for selling soil carbon offsets but also lead to other opportunities in water improvement, biodiversity improvement and higher quality produce coming from these farms.

The Gentle Farming system will produce the first carbon offset certificates in the Autumn. The focus will be to build a website that gives a shop window to each individual farm by creating a profile that highlights the story of their farm and the environmentally beneficial work they do. The buyers can see a portfolio of local farms or those that reflect their needs. Gentle farming will sell the offsets and begin paying farmers this winter. I hope that having a group of high-quality soil focused farmers and a system to verify their carbon offset will lead to other opportunities within their community and supply chains, for example selling grain at a premium price, investment in environmental projects, marketing for other diversification projects.

Marketing this in the right way with the right story and a young ambitious brand to sit alongside it I believe has the greatest potential to make a difference in terms of rewarding and recognising the hard work that goes into being a nature focused farmer. I think that regenerative/ sustainable farming practices are going to boom in the next decade and the farmers already on this journey can and should lead the way. Most people talk about all the problems coming in the future, I can’t help but smile and all I see is opportunities to make a difference and encourage more people to love the soil that feeds us.

-

Proposing A Solution To Boost Biological Product Adoption

Could a Biologicals Pipeline Accelerator and Demonstrator be the conduit to improving the uptake of novel crop protection products within UK agriculture?

CHAP Innovation Network Lead, Dr Harry Langford and Research Associate, Dr Jemma Taylor, are part of a team that has developed a business case proposing just that. Through CHAP’s New Innovations Programme, which brings together skilled practitioners and technical specialists to define critical realworld challenges, potential ideas for overcoming areas of market failure are scoped. From this, business cases are formulated with a view to overcoming a shared sector challenge, in this case, the adoption of biological products. Reporting on the business case, Dr Langford and Dr Taylor provide sector insight, share the proposed solution and draw in knowledge from industry advocates of biological plant protection.

The why, the reason

Biological plant protection products are a distinct group within the crop protection market, set apart in that the active substances are derived from living organisms. This can encompass pest control by using non-toxic mechanisms such as pheromones in conjunction with traps, predatory macroorganisms, microorganisms as the active ingredient, or substances produced by plants, either naturally or through targeted modification.

They are recognised as having significant potential to deliver crop protection outcomes in a sustainable way, meaning they are ideally placed to deliver solutions in systems where traditional synthetic products can’t or should not be used, such as in organic farming and regenerative agriculture. With the increasing interest in these alternative farming methods, biologicals have a bright future.

Biologicals can, and are already, being used across a wide range of crops grown worldwide, as they can help to improve quality and yield. They are used most effectively as part of an integrated pest management (IPM) system to complement other products and methods designed to keep the crop as healthy and productive as possible. Many biologicals can be applied using the same equipment as regular crop protection products, increasing their uptake and application by farmers. However, they do often have specified storage conditions and application times and rates, which users need to adhere to, to ensure efficacy.

The biologicals market can be segmented by type (macro-organisms, microbials and biochemicals), use (biofungicides, bioinsecticides, and bionematicides), or mode of application (foliar spray, soil application and seed treatment) to help apportion the marketplace and identify comparables. It is a growing global market due to a condensed regulatory timeline, reduced chemical residues and environment persistence, and compatibility with alternative farming methods such as organic and regenerative agriculture. Today the market is worth about $4.3bn, or £3.1bn.

In the UK, a growing number of established companies, SMEs and startups are investing in this market. This is encouraging, due to growing concerns around the efficacy of more traditional crop protection solutions due to resistance issues, synthetic product revocations and the decline in new products reaching the market, as well as ongoing environmental concerns.

Therefore, the acceleration of the biologicals market provides a significant opportunity to reduce the environmental impact of crop protection, improve IPM, and drive the development of a new sustainable skillset within farming. However, the challenges for biologicals can include variable effectiveness, unstable formulations and a different grower mindset to their useage. Consequently, small companies and research institutions can struggle to develop new biological products from discovery through to market launch.

We want to see what role CHAP could play in overcoming these challenges

Analysing the market

There are a number of public and private sector advisors and facilities that help support biological product development and testing. Challenges here include the fact that they can be shared with other sectors, underutilised or suffering from a lack of exposure, or they are not focused on the optimisation of biologicals at a farm scale within the context of IPM.

Understanding why these do not fulfil the market need in stimulating scale-up and commercialisation needs further investigation, but other factors could include a lack of capacity, high charges against a company’s limited resources, or a lack of awareness of what facilities are available.

Others who are operating in this area are:

• Consultants who are specialist regulatory advisors, e.g. Enviresearch

• Research and scale-up facilities with specialist equipment, e.g. CPI and IBiolC, along with industrial biotechnology facilities

• Business advisors – public and private, e.g. Cambridge Consultants

• Public sector providers of grant funding, e.g. Innovate UK

• Venture capitalists and business angels, e.g. Yield Lab

• Associations promoting relevant applied research, e.g. AAB

There are already a number of public sector advisory and support organisations, and/or those who provide grants for this area. With this in mind, there is an opportunity for CHAP to establish the core of a service which would provide advisors to help companies advance through the new product development pipeline, and direct them to resources and facilities that are available either within CHAP or elsewhere, to help them to progress. This would enable a complete pipeline provision:

• Small scale production facilities and equipment

• A network of field and farm trial sites optimised for biologicals

• Advice on research and testing design

• Guidance on regulatory submissions and evidence

• Advice on further research and technology development

• Grant funding for future development

• Business and commercial training

• Overall advisor to progress pipeline

• Lab and testing equipment

• Consultants for regulatory advice

• Grant and loan funds for specific projects.

The case for change

During an assessment of the UK crop protection industry, CHAP identified three main areas of market failure:

• Funding: Risk for developers of new biological IPM products and systems, along with challenges demonstrating efficacy and best practice, leading to difficulties in securing funding to move products along the ‘ pipeline’.

• Understanding: Lack of clear information, both for SME product developers, in addressing development and demonstration challenges, both to move new IPM products and systems along the pipeline, and to help end users understand the product and system choice.

• Tailoring: Global, large market focus hinders the development of biological solutions tailored to local situations and smaller markets.

Alongside these market failures, several barriers were identified which slow or prohibit progress with the development, production and utilisation of biological crop protection products. The market for biological control products may be on the rise, but challenges remain for the numerous SMEs developing them, especially the availability of independent facilities for scale-up of production. This is particularly true for certain product derivatives such as fungi, which require dry-mill biorefining. Beyond production, barriers to adoption include demonstrating biologicals’ efficacy, and a more complex use strategy with many best used in association with other products or IPM strategies (but with little knowledge and information available to support users).

As a result, new biologicals often either stall and fail, or are purchased by larger companies during their early development, with limited benefit either to the original investors or to the UK economy. These barriers – coupled with the high cost to growers for biopesticides when compared to synthetic pesticides – restrict their adoption in more conventional broad-acre farming systems. This may ultimately limit the growth of the global biopesticides market. As the new agriculture bill and ELMS regulations come into force in the UK, changes will be implemented to encourage more diverse, sustainable and environmentally benign farming systems.

This will only add to the highly complex, multi-dimensional space of the crop protection ‘environment’, which is trying to interface between ‘science’, ‘agricultural technologies’, ‘crop management practices’, ‘environmental impact’, and an ever-growing public scrutiny of the environment and public health. This is concerning as it is already difficult for stakeholders in the sector to keep up-to-date with legislation and evolving products and solutions, and to therefore make good decisions about what products to use and where the business opportunities are.

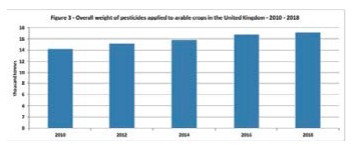

The majority of UK farmers have a risk-averse view of pest management and undertake ‘insurance’ applications; in fact, pesticide applications on UK crop land rose 24% from 2000 to 2016. Setting up an effective IPM strategy is important when trying to deal with production risks, but with the multitude of traditional and new crop protection tools and technologies available, and the complexity and clarity of the information surrounding IPM programmes, this itself can be a major barrier to the correct and effective adoption of IPM.

To address this CHAP, in discussion with stakeholders from across the sector, created a problem statement to summarise the issues and opportunities for which a solution could then be developed. Risk prevents truly disruptive crop protection solutions from being developed and delivered, particularly as part of an integrated system. Manifold risks operate across the product development and regulatory pipeline, in accessing and utilising real-time data to underpin user decision-making, and in designing systems-integratable solutions.

Solution – a collaborative way forward

To address this problem statement, CHAP proposes the development of a ‘Biologicals Pipeline Accelerator and Demonstrator’ in partnership with key stakeholders. This would increase the number of new biological products successfully reaching market, and improve the effective integration of biologicals into existing and novel IPM strategies, diversifying their use cases to include open field agriculture.

The Biologicals Pipeline consists of two parts

• The ‘Accelerator’ – a brokering service to link SMEs to expertise and facilities along the development pipeline, with expertise in specific activities, such as scale-up of production, adjuvant/inert material specialists, biological and toxicological testing, regulatory compliance, product registration, investment and funding. This will provide a one-stop-shop for innovation in biologicals, from registration and compliance through to scaleup and financing.

• The ‘Demonstrator’ – a network of field and farm trial sites optimised for biologicals and IPM, providing two tiers of demonstration trials: efficacy trials of new products, singularly and in combination; and IPM optimisation trials to develop standard operating procedures for biological IPM solutions. This will allow product developers to determine and, if necessary, reduce the variability of their product’s efficacy, as well as allowing application mode and delivery to be optimised within a commercial IPM setting. As such, the ‘Demonstrator’ will help to overcome technical limitations of biological products during the product-development pipeline, and showcase the efficacy of products within optimised IPM systems, helping to de-risk these products and systems for the end-user.

After demonstrating a successful service, the Biologicals Pipeline Accelerator and Demonstrator could expand further, via strategic capital infrastructure investment, to provide supporting equipment where strong market need is evidenced. It is anticipated that primary users of the Pipeline will be SMEs at an early stage of biological product development, who are seeking to advance products through the pipeline towards the market, along with researchers in universities and research institutes at an early stage of biologicals source or product development. Contract researchers may also find it beneficial.

CHAP hopes that the Biologicals Pipeline Accelerator and Demonstrator will benefit farmers and anyone in the agricultural sector who uses the novel products that come out of the Pipeline, as well as benefiting wider society due to more sustainable food production and a resilient farming sector.

-

‘Pasture For Life’ Makes Good Financial Sense

Farmers who only ever feed pasture plants to their animals often remark on the positive effect this has on their bank balance. Sara Gregson talks to one such farmer and also reveals the findings of a recent economic survey of members of the PastureFed Livestock Association (PFLA)…

Balbirnie Home Farm in Fife has been in Johnnie Balfour’s family for generations. It is a mature mixed farming business running to 1,300 hectares and used to grow cereals, beans and vegetables, with some permanent pasture alongside an intensive beef finishing system. A 250-cow robotic dairy business was closed in 2005 because it was losing money. The soil ranges from silty loam to sandy loam and average rainfall stands at 700mm.

“When my father retired in 2018, I was reading a lot about regenerative farming and had recently completed a post-graduate course in Sustainable Agriculture,” says Johnnie. “I had also joined the Pasture-Fed Livestock Association whilst living in Hong Kong, where I had been for three years. It sounds a bit surreal, but looking out over all the skyscrapers and high-rise apartments was when I realised I wanted our herd at home to be pasture-fed.”

Previously the beef cattle had been fed a barley creep feed when grazing with their mothers. They were brought inside in October and fed a high cereal diet. Mainly Simmentals crossed with a big Charolais terminal sire, some finished with carcases weighing more than 400kg, grading U and 4R at around 16 months of age.

“They looked impressive and were securing high prices at the market,” says Johnnie. “But we were actually spending much more than we were getting back. There were a lot of fixed costs from the daily use of tractors, feeder wagons and labour, we were ‘buying in’ barley from the arable side of the farm and making a lot of conserved forage that had to be made, stored and carted. I was much more interested in not having machinery doing the jobs that the cattle can do for themselves.”

Mob grazing

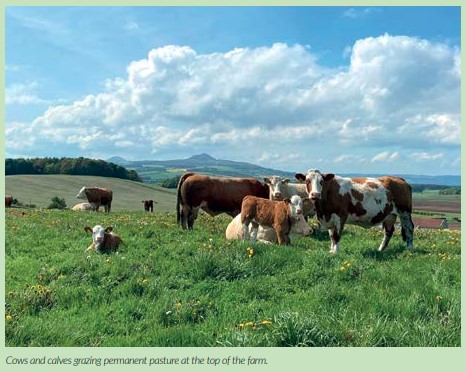

Now the cattle business looks very different. There has been a move away from the big continental breeds towards Salers and Aberdeen Angus easy-calving bulls, which have been chosen so that calves pop out unaided and producing progeny that grow well off grass alone. The most significant change has been the management of the grass. Being part of a three-year mobgrazing discussion group, as part of a Soil Association Scotland Field Lab scheme, has helped.

“We have learned so much, sharing the highs and lows of trying to start mob grazing,” Johnnies admits. “As well as the permanent pasture we have at the higher end of the farm (250 metres), we now also have short term mixed leys growing within the arable rotation. The fields growing cereals and vegetables were never rested, and now they have a rejuvenating multi-year ley within them. “We graze the 170 suckler cows in two mobs and aim to do daily moves. At all times we are trying to lengthen the rest period – this is the most important element of mob grazing. This is what we really need to focus on, not the amount of grass that is growing or the residual left after the cattle have grazed.”

Calves used to be weaned at the beginning of October but if there is enough grass, the aim is to keep them out until Christmas. The youngstock will then overwinter on kale with big bales of silage.

“Mob grazing forces you to do a plan,” Johnnie explains. “By working out expected supply and demand, animals can be sold early in a season if a grass shortage is predicted weeks down the line. Some stores we sold this spring made really good prices.”

Pasture for Life

Balbirnie Farms became Pasture for Life certified last year, meaning none of the cattle ever eat anything other than grass, pasture or forage crops their entire lives. They are sold to Macduff Beef, a Pasture for Life certified butcher.

“We are definitely going in the right direction, but still have much to learn. In our beef enterprise we have already cut our variable and fixed costs significantly, our cattle are happy and healthy, and their actions are improving the soils beneath their feet, which is all very positive.”

Gathering The Evidence

A recent research project called ‘Sustainable Ecological and Economic Grazing Systems: Learning from Innovative Practitioners’ has given some hints to what effect feeding cattle and sheep on just pasture has on Gross Margins. The research was carried out by the UK centre for Ecology and Hydrology (UKCEH), Lancaster University, Natural England and SRUC, and led by Dr Lisa Norton of UKCEH. The project was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Economic and Social Research Council, the Natural Environment Council and Scottish Government.

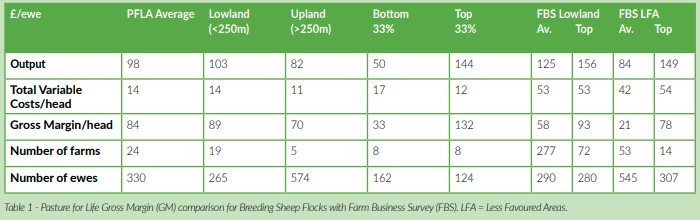

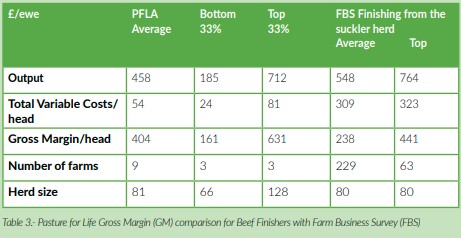

Fifty-six Pasture-Fed Livestock Association (PFLA) members were interviewed on all aspects of their farming systems, including their finances. Their Gross Margin figures (Output minus Variable Costs) have been compared to the Farm Business Survey (FBS) for England – see Tables 1,2 and 3.

The top PFLA farms are making more Gross Margin at £132/head than the top FBS farmers at £93/ head (on the Table 1 in green).

PFLA farms based in the uplands have a much better Gross Margin at £70/head than the average upland farm in the FBS survey at £21/head (on Table 1 in blue).

The main reason for these results is that the variable costs on the PFLA farms is much lower than for the FBS farms – at £14/head average for PFLA, compared to £53/head for the lowland FBS average and top farms (on Table 1 in orange). These costs would include concentrate feed and vet and med bills. The output from the PFLA farms is almost double that of the benchmarked FBS farms at £1,158/ head for the average compared to £516 and £540 for the FBS averages for lowland and upland systems (on Table 2 in blue). The probable reason for this is that the PFLA farms are selling their calves finished, whereas the FBS farms are selling six-month-old stores for other farmers to finish.

However, despite PFLA farms keeping their cattle six months longer or more, the variable costs across all the systems were remarkably similar, from £193/head for the PFLA average and £216/£214 for the FBS averages for lowland and upland (on Table 2 in green). In essence, PFLA farmers are achieving twice as much output for the same amount of variable costs. When looking at an enterprise level – the FBS lowland farms are achieving an income of just £18,576 (£516 x 36 cows), whilst the PFLA farms are gaining £59,058 (1,158 x 51 cows). Output from the PFLA farms is significantly lower than the FBS documented enterprises at £458/ head compared to £548/head (on Table 3 in blue). This will probably be because the PFLA cattle are native breeds and their growth is not being pushed on by grain feeding.

However, once again there is wide variation in the variable costs between the two approaches, with PFLA costs sitting at £54/head compared to £309/head for the FBS sample (on Table 3 in blue). This will be due to PFLA animals being fed no expensive grain or concentrates. This leads to the PFLA farms having a much healthier average Gross Margin of £404/head, as opposed to the FBS farms at an average of £238 (shown on Table 3 in orange).

In future, the PFLA is looking to gather and produce enterprise costings data down to Net Margin level, to highlight differences in fixed costs between 100% pasture-fed farmers and conventional lamb and beef producers.

-

Industrial Hemp Understanding The Opportunity For UK Farmers

This article was “Written by Camilla Hayselden-Ashby, Nuffield Scholar 2021

Hemp, Cannabis with a low level of the psychoactive compound THC (tetrahydrocannabinol), has seen a global upsurge in interest in the last decade. This has been driven by the growing popularity of CBD as a food supplement, demand for environmentally sustainable products and changes in legislation around cannabis growing. The global hemp market is projected to reach $15.26 billion by 2027.