If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

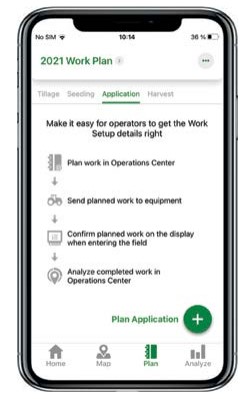

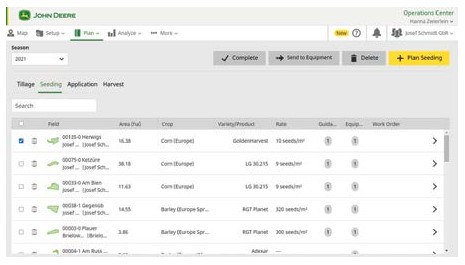

JOHN DEERE – FUTURE OF FARMING

Changes in weather patterns are just one of many challenges farming is facing. John Deere is investing huge resources into solving these challenges. Three core technologies are shaping the future: Electrification, Automation to Autonomy and Artificial Intelligence.

Electrification

Electrification isn’t just about using batteries as the power source. It’s about using electrical drives to replace engines and hydraulics. Electric motors have huge torque at low speeds, they’re more efficient, more reliable and lighter.

eAutoPowr transmission: eAutoPowr is the first continuously variable transmission with an electromechanical power split. Compared to conventional CVTs, the drive is more efficient and wear-free. Another special feature is the provision of up to 100kW of electrical power for external consumption. To demonstrate this, John Deere and Joskin have developed a slurry tanker with two electric drive axles. Thanks to this eight-wheel drive system, a much more efficient transmission of tractive power is possible. This can also reduce slurry incorporation costs by up to 25 per cent.

VoloDrone – The large drone developed jointly by John Deere and Volocopter has a diameter of 9.2 m and is powered by 18 rotors. It has a fully electric drive with replaceable lithium-ion batteries. One battery charge allows a flight time of up to 30 minutes, and the VoloDrone can be operated both remotely and automatically, on a preprogrammed route. The drone frame is equipped with a flexible standardised payload attachment system. This means that different devices can be mounted on the frame, depending on the application. For crop protection, the large drone is equipped with two liquid tanks, a pump and a spray bar. Thanks to the low flying height, very large area coverage of up to 6ha/hr can be achieved.

Autonomy through automation

The focus of automation is not to replace the operator. It’s about using technology to create the best operator possible. The journey began with hands-free AutoTrac satellite guidance to steer the machine. Now we have Integrated Combine Adjust on our S700 combines which makes real-time automatic adjustments to maintain the pre-set levels.

Autonomous electric tractor – John Deere’s new autonomous tractor concept is a very compact electric drive unit with integrated attachment. The tractor has a total output of 500 kW and can be equipped with either wheels or tracks. Flexible ballasting from 5 to 15 tonnes is possible, depending on the application, to help reduce soil compaction. Thanks to the electric drive, there are no operating emissions and noise levels are extremely low. Further advantages include low wear and maintenance costs.

Semi-autonomous tractor – This tractor drives semi-autonomously and is equipped with an integrated crop sprayer. Using a built-in camera, it is possible to work in row crops – for example, applying plant protection products to fruit tree orchards. Filling the sprayer tank is fully automatic at the filling station, so the user is not exposed to pesticides. This is designed to reduce costs and increase productivity by over 30 per cent.

Autonomous sprayer – This novel autonomous sprayer is lighter than a conventional self-propelled sprayer and has a 560 litre spray tank. It can enter fields after rain without causing any soil compaction. The high ground clearance of 1.9 m and four-wheel steering make it extremely versatile, while the tracks minimise ground pressure and greatly extend the operating window.

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence is changing the way we spray.

See & Spray – With See & Spray technology, high-resolution cameras capture 20 images per second. Based on the images and artificial intelligence, the system recognises the difference between cultivated plants and weeds so that individual plants can be specifically treated.

With this new generation of weed control, the use of pesticides can be greatly reduced.

CommandCab – Whatever happens in the future, the farmer will always be in control. Our Command Cab shows how the journey from Automation to Autonomy is likely to evolve. The future vision of a driver’s cab reveals new possibilities for artificial intelligence. With its joystick control, touchscreen display and networking of all machine components, it´s a completely new operating concept. By integrating real-time weather data, individual pre-settings and job management procedures, the cab becomes the command centre for agricultural operations.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

BUSY BACKEND AND DISCUSSIONS WITH THE NEIGH SAYERS!

Having travelled all over the country with the Ma/Ag drill we are now beginning to see the results of our toils which seem positive. As always during demonstration, we have visits from the next door neighbour, some with positives comments and some not quite so. On one demonstration which I and the farmer where more than happy with, the visiting cousin was negative to say the least. After his departure, I spoke to the farmer about his cousin’s opinion, and had the response that he was very positive until I stepped out of the cab!

I have grown a little tired of the comments that direct drills are only a dry weather tool, we have proved that providing you can travel without making a mess on the surface, and providing your equipment is suitably tyred and correctly operated so as not to do damage underneath the surface then pretty much anything is possible. In fact where cover crops have been grown or last year’s crop aftermath is still around, these can allow operations where bare cultivated ground might not.

Here is a riverbank field, an attempt was made to plough but soon given up, we direct drilled the spring barley into reasonable conditions, all was well until we ventured into the ploughing which appear reasonably dry, it wasn’t! Lesson learned, a 2 ton crop of spring barley (drilled 20.4.18), apart from the ploughed ground, which just grew weeds!

Direct drilling 14 tons/Ploughing 0

I rest my case!

Mark Harrison, Ryetec Ltd

-

Agronomist In Focus Dick Neale

FROM HUTCHINSONS

Catch and cover crop choices play significant part in positive transition to Sustainable Farming Initiative When any new technique is employed its initial benchmark for success is a measure of the financial return it provides over the technique it replaces or enhances. In that respect cover crops have had a rocky start in their introduction to UK agriculture. This is largely because the financial positives or negatives a cover crop brings in the initial stages of introduction are marginal with the potential for a negative financial impact often overriding the positive. However, measuring a catch or cover crops success or value based purely on one year’s yield impact fails to recognise the significant improvements in soil structural health, biology, nutrient flow and water management their use imparts over time.

Increasingly research is demonstrating the importance of below ground biomass in the building of soil organic matter (SOM) with figures recording over 40% of root matter being retained as SOM while top growth contributes only 8% to SOM. Cash crops must not be forgotten in the process of building SOM but catch and cover crops play a vital role in filling the gaps in rotational cropping, in particular being present during the August to November period when UK soils are traditionally bare from post-harvest cultivation. The value of catch and cover crops is immense when sown in August to intercept those longer days of sunlight energy and recharge the soils biological battery.

Choose a cover that works for your situation

Choice of cover is crucial to optimise performance, address identified issues on individual fields and match the farms management approach out of the cover period, be that grazing, rolling, spray and direct drilling or cultivation. Covers can be used to address carbon: nitrogen ratios within the soil which can impact the soils’ ability to ‘digest’ high lignin residue like wheat straw, equally they can be used to slow the ‘burn rate’ of SOM in lighter soil fractions. The focus is knowing what the state the soil is in and what it needs. Cover crops can be used to add significant diversity into rotations and are an ideal opportunity to get legumes into the cropping cycles and reduce reliance on applied artificial nitrogen. Following crops must be considered as there is significant risk of yield reduction where oats or rye are a high proportion of the cover crop mix prior to spring barley or wheat. Where cereals dominate the rotation ,utilising oats as the cover adds little in diversification terms.

Consistently successful cover crops are made up of multiple species. The species mix should be optimised to the targeted impact required whilst bringing diversity, nutrient fixation, storage and release. Ease of use like seed flow characteristics through air seeders and overall rates of use to fit with smaller air seeder hoppers is a further consideration along with reliability of species with the UK climate.

We have made sure Hutchinson’s mixtures have been optimised for reliability and performance. Typically, our mixtures contain 8 species with the previous crop volunteers making it a 9 species population. Ratios in the mixtures are adjusted to optimise the area of performance, be that soil structural impact, nutrient release and fixation, water pumping or surface protection.

As details of the Sustainable Farming Initiative become clearer it leaves little doubt that cover crops, reduced cultivation practices and soil assessment and improvement will be central to accessing support funds in the future. Transition from one cultivation system to another takes time both for growers to gain confidence in the new approach and for soil to react and improve, now is an ideal time to make the change while support payments remain to help counter the risks and tweaks required for any system as it establishes itself on farm.

-

New Miscanthus Finance And End-User Offtake Agreements Assist UK Decarbonisation

In an industry first, farmers considering planting the carbon negative crop Miscanthus can now benefit from a finance package to cover virtually all upfront costs for crop establishment, as well as new direct, long-term offtake agreements with end-users, with 10–15-year index-linked annual returns.

The new opportunity has been launched to help support the growing need to decarbonise the UK economy with bio-based solutions, and if planting of perennial crops such as Miscanthus is accelerated quickly, to at least 30,000 hectares per year by 2035, this increase could sequester 2 MtCO2e by 2035 and over 6 MtCO2e by 20501.

Oxbury Bank is working in partnership with Miscanthus specialist, Terravesta, to deliver the new finance package, which is supporting farmers to plant and establish the crop. “One of the main barriers to entry for Miscanthus growing is the upfront cost of planting. Our finance package with Terravesta ensures a quick release of funds to help farmers to grow a sustainable business. The loan structure allows farmers to pay interest only for up to two years while the crop is establishing and then pay back the capital over an extended period of time when the crop is producing an economic return,” says Nick Evans, managing director of Oxbury Bank.

“Agriculture is changing, and it’s important that farmers have access to finance and capital for their low carbon initiatives and sustainable growth plans, like Miscanthus,” says Mr Evans.

Under the new contract, Terravesta will supply its Performance Hybrids, planting equipment and agronomy throughout the crop’s life, ensuring successful crop establishment by committing to a minimum number of plants emerging under its new planting promise. “Our current rhizome-based variety Terravesta AthenaTM delivers higher yields than the commercially available Miscanthus giganteus, a calorific value increase of 8%, resulting in 180% increase in energy per hectare (megajoules) and significant ash content reduction, all of which benefits the end-user considerably,” explains Alex Robinson Terravesta’s chief operating officer.

“Terravesta AthenaTM generally takes its first harvest in year two and reaches maturity faster than Miscanthus giganteus, and some of our growers are reporting a first harvest of eight tonnes per hectare, going onto a mature yield of between 10 -17 tonnes per hectare depending on the soil type.

“The beauty of this new package is that growers have a direct contract with renewable energy power plants, which enables Terravesta to provide a finance package and allows us to focus on crop establishment in the UK at a much greater scale to support our net zero targets,” adds Mr Robinson.

To learn more visit:

www.terravesta.com/learnmore.

-

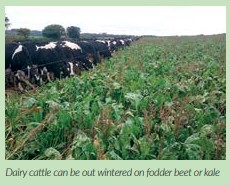

Does Grazing Cover Crops Negatively Impact Soil And Crop Yields?

Separation of crop and livestock production can degrade soil and other natural resources while reducing economic returns. Additionally, the conversion of grassland to cropland has put a strain on forage for cattle. Grazing cover crops can be a potential option to re-integrate crops with livestock production and reverse the adverse effects of separating crops and livestock production. Grazing cover crops could still maintain the benefits from cover crops as roots and some stubble remain after grazing. Cover crop grazing has shown to improve economic returns (Franzluebbers and Stuedemann, 2007) while still capturing benefits from cover crops (Faé et al., 2009; Maughan et al., 2009); however, soil compaction risks can be a concern.

Written by Lindsey Anderson, Humberto Blanco, Mary Drewnoski and Jim MacDonald, Published in CropWatch

from the University of Nebraska-LincolnWhile there are few studies evaluating cover crop grazing, most of the existing studies found any shallow soil compaction that did occur was not enough to influence yields. Tillage and soil wetness could influence the impact of cover crop grazing on soil compaction. A study under strip tillage in west central Nebraska found that grazing cover crops increased soil compaction in one of three years, but it is possible strip tillage may have alleviated potential compaction in the other two years (Blanco-Canqui, et al., 2020).

On the other hand, a study in Georgia found that compaction increased more when grazing under conventional tillage (disk plowing to 6-8 in.) compared to grazing under no-till (Franzluebbers and Stuedemann, 2008). This suggests conservation tillage, such as no till or strip till, could be more beneficial than conventional tillage when grazing cover crops. Another study in Georgia found cover crop grazing in the spring after an above-average rainfall increased soil compaction due to soil wetness and thus reduced cotton yields (Schomberg et al., 2014). Thus, soil wetness is also important to consider when cover crop grazing.

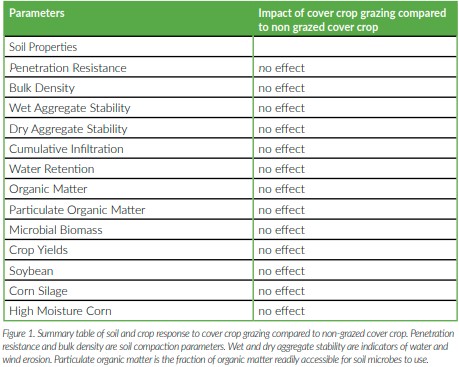

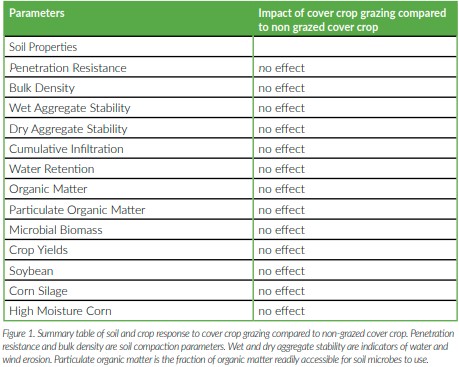

To further improve our understanding of how cover crop grazing may affect soil properties and crop yields, we conducted a study in 2019 and 2020 on a field-scale oat cover crop grazing experiment under an irrigated no-till corn-soybean rotation on silt loam soils in eastern Nebraska. Our results suggest that fall/winter cover crop grazing does not negatively impact soil or crop yields (Figure 1). These results are similar to other fall/winter cover crop grazing studies, but it should also be noted our study only had cover crop following the corn phase of the rotation, thus grazing only occurred every other year, possibly reducing any cumulative impacts of grazing.

Field Management

Our cover crop grazing experiment was established in 2015 at the Eastern Nebraska Research and Education Center near Mead, Nebraska. There were two study fields in this experiment, and each field was 52 acres under center pivot irrigation and no-till. The rotation was corn-soybean, and each field was cut in half and harvested as corn silage in one-half of the field and high moisture corn in the other half of the field. Corn silage was harvested around Sept. 1 and high moisture corn (about 32% moisture) harvested around Sept. 15, about 25 days before typical dry corn (about 15% moisture) harvest. A cover crop of Horsepower oat was drilled at 96 lbs per acre following corn harvest (Figure 2). Following cover crop planting, the fields received 40 lbs N per acre from ammonium nitrate. No cover crop was planted following soybean harvest.

Cattle Management

Cattle grazed from November to December at stocking rates ranging from 0.6 to 1.7 head per acre, with cattle initial weights ranging from 507 to 553 pounds throughout the study. The stocking rates were calculated based on a target grazing period of 70 days and accounted for cover crop biomass under corn silage and both cover crop biomass plus corn residue amount under high moisture corn. Forage allowance was about 25.6 pounds per steer per day in the first two years and about 39.0 pounds per steer per day in the last three years. Grazing only occurred in late fall/winter following the corn phase of the rotation with grazing durations ranged from 30 to 69 days over the five year experiment. Based on the rotation, grazing occurred twice in one field and three times in the other field over a five year period.

Did Cover Crop Grazing

Damage Soils?Cover crop grazing had no impact on soil compaction, wind or water erosion potential (expressed as wet and dry aggregate stability), water infiltration, water retention, organic matter, particulate organic matter (fraction of organic matter readily accessible to soil microbes), or microbial biomass compared to the non-grazed cover crop (Figure 1). These findings strongly suggest that cover crop grazing does not damage soils.

Why Might Grazing Not Impact

Soils?It is believed cover crop grazing had no impact on soil compaction in this experiment because:

1. Grazing only occurred after the corn phase of the corn-soybean rotation, which reduced the frequency of grazing (every other year grazing).

2. The experiment was located on soil with high soil organic matter (4.2% within 0 to 8 inches) and soil organic matter can prevent soil compaction.

3. Grazing occurred in late fall when the soil is less likely to be wet compared to spring, with spring having more rainfall.

4. Natural freeze-thaw and wettingdrying soil cycles can naturally break up any potential soil compaction.

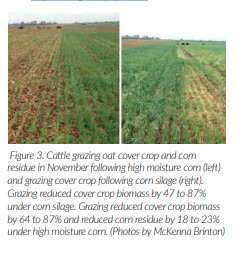

Cover crop grazing removed about 47 to 87% of cover crop biomass due to cattle intake and trampling (Figure 3). However, much of the biomass removed was actually incorporated into the soil surface from trampling, retaining cover crop residue within the system. Additionally, cattle intake removes little nutrients from the system, as cattle excrete most of the nutrients consumed during grazing. For these reasons above, we believe cover crop grazing in this study may have had no negative impact on soil properties due to the addition of trampled cover crop aboveground biomass, cover crop root biomass and infrequency of grazing (every other year).

Did Cover Crop Grazing Impact

Crop Yields?Cover crop grazing had no impact on soybean or corn yields (Figure 1), which is similar to previous cover crop grazing experiments. Only two studies report yield decreases from cover crop grazing during wet soil conditions in spring (Schomberg et al. 2014) or increased soil water evaporation from summer cover crop grazing reducing residue cover (Franzluebbers and Stuedemann, 2007). Our study site was irrigated and grazed in fall/winter.

Should I Graze My Cover

Crops?• In this study, cover crop grazing had no impact on soil compaction, wind or water erosion potential, water infiltration, water retention, organic matter, particulate organic matter or microbial biomass compared to the non-grazed cover crop. Therefore, based on the conditions of this study, fall/winter cover crop grazing had no negative impacts on soil properties. Additionally, cover crop grazing had no impact on crop yields.

• In previous studies, cover crop grazing can have some impact on soil compaction, depending on tillage system and soil conditions at time of grazing. Based on what little research is available, it is suggested conservation tillage — such as no till or strip till — may prevent possible accumulated impacts of compaction, but conventional tillage should be avoided.

• Based on our experiment and others, cover crop grazing could be a strategy to re-integrate crop and livestock production without largely degrading soil properties or impacting crop yields.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nebraska Environmental Trust and the USDA SARE for their funding of this research. Also, we thank Kallie Calus, McKenna Brinton, Benjamin Hansen, Kristen Ulmer, Zachary Carlson and Fred Hilscher for their work on this research. Additionally, we thank Mark Schroeder and team at the Eastern Nebraska Research and Education Center for field management, Husker Genetics for acquiring and planting oats, Elizabeth Jeske for soil microbial analysis, and all undergraduate and graduate students assisting with fieldwork.

-

The Plant Microbiome: An Introduction

Written by Joel Williams

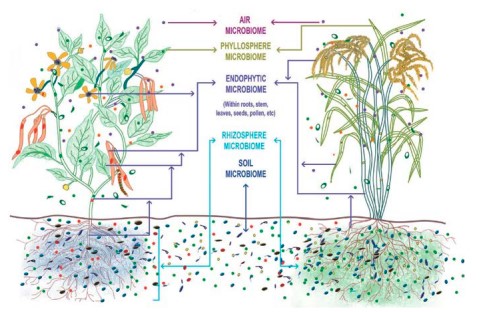

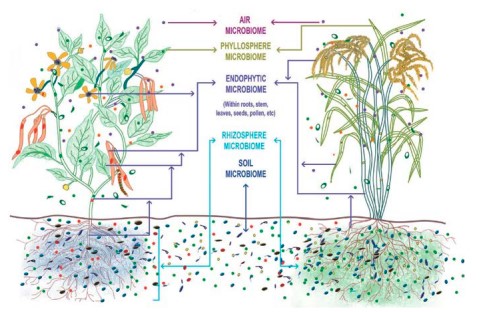

Soil Biology – two words that have become commonplace in the lexicon of the farming community in recent years, and rightly so. Biological interactions are of course as important as the physical and chemical interactions that make up the fascinating medium we call soil. Among all the groups of organisms that live in soil, there has been a particular growing focus on the microorganisms; interest in which gained significant traction as we began using more powerful tools to study them – genetic and molecular tools for example. As we began to unearth the world of the soil microbiota, we quickly realised just how vast and complex this underground universe really is – certainly much more so than previously thought. In dealing with this complexity, one branch of research has shifted attention away from the soil to study the microorganisms that are associated with plant tissues – enter the plant microbiome.

The plant microbiome – also known as the phytomicrobiome – refers to the groups of microorganisms that are intimately and directly associated either on or within various plant tissues. The number and diversity of organisms that make up the plant microbiome is a fraction of what is found in the bulk soil, hence the emerging focus on studying this less complex plantassociated ecosystem. Please note, I use the words ‘less complex’ very cautiously here – arguably, there is nothing ‘less complex’ about it at all apart from having less diversity and density of organisms.

I’m sure most readers will be familiar with the below ground community of microbes known as the rhizosphere but the above ground plant habitats are collectively known as the phyllosphere. These microbial communities consist of bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, algae, and occasionally nematodes and protozoa (these latter two are much more common down below in the rhizosphere but less so above ground). Bacteria are by far the most commonly found microbe above ground in terms of both numbers and diversity. All of these microbes that associate with the plant are either acquired from the environment (soil and atmosphere) or they are inherited from the mother plant via the seed.

Within each of the plant associated habitats, some microbes live inside the plant tissues (endophytes) while others will remain outside of the plant, living on the surfaces (epiphytes). There is some overlap between the microbes that associate on various plant parts, but surprisingly, many of the species are totally unique and distinct from each other, fulfilling very specific roles and functions within each of their micro-habitats. Let’s briefly explore some of the different regions of the phytomicrobiome:

Root microbiome – often referred to as the rhizosphere, this is of course the microbes who associate with plant root systems. Arguably the most well studied of all plant microbiomes, the organisms in the rhizosphere play particularly important roles for nutrient acquisition, plant immunity and resilience during environmental stresses.

Shoot microbiome – the microbes that dwell in shoot tissues appear to be more closely related to the species found in the soil highlighting the soil as an important primary source of organisms which colonise the plant. The endophytes found in the shoot are highly mobile within the plant and are also commonly found in the seed – forming part of the seed microbiome for the next generation.

Leaf microbiome – the leaf microbiome has been shown to influence photosynthesis and transpiration hence playing a vital role in plant development, particularly under difficult climatic and weather conditions.

Flower microbiome – our understanding of the microbial communities that uniquely associate with flowers is far less when compared to other above ground plant habitats. This is particularly due to the fact that these attractive habitats receive more regular visitation by a diverse range of insects who facilitate transfer of other beneficial and pathogenic microbes; as well as inadvertently leaving a fingerprint of their own insect-associated microbiota. As you might guess, the organisms associated with flowers have been implicated in influencing plant reproductive success – they have even been shown to use flower scents (volatile organic compounds) as a food source and additionally induce distinct changes in the expression of a plants floral scents.

Seed microbiome – like other parts of the plant, the seeds are also colonised with a diverse group of microbiota. At the end of reproductive development, the organisms on and within seeds act as a reservoir for the next generation and typically establish as endophytes in next years offspring. Functionally speaking, the seed microbiota release a range of metabolic substances that enhance germination and establishment as well as plant performance and productivity under stressful conditions. We will return to the seed microbiome in the next issue of Direct Driller and will expand on this article with a deeper dive specifically into the role of the seed microbiome.

Altogether, the plant microbiome directly and indirectly influences plant performance, productivity and can support low input production systems. Direct mechanisms that support plant growth include nutrient supply via solubilisation from soil reserves or biological nitrogen fixation, as well as production of plant growth promoting hormones. Indirectly, plants can also recruit specific microbes to help them overcome various biotic and abiotic stresses – such as activation of beneficial microbes who can suppress pathogens or improve drought resistance.

There is an increasingly prominent nudge towards reducing fertiliser and pesticide use in agriculture from both top-down (policy) and bottomup (consumer driven). There is significant potential in the use of DIY or commercial microbial inoculants to support this transition, however, many challenges remain regarding improving product consistency in field conditions. Central to achieving this is the need for a deeper understanding of the ecological processes and mechanisms that underpin the plant microbiome assembly and function. Addressing these knowledge gaps will no doubt help provide the necessary tools to support agricultures transition toward ecological and productive sustainability.

References

1. Understanding phytomicrobiome: A potential reservoir for better crop management. (2020). doi: 10.3390/su12135446

2. Phytomicrobiome for promoting sustainable agriculture and food security: Opportunities, challenges, and solutions. (2021). doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2021.126763

3. Plant microbiome: A reservoir of novel genes and metabolites. (2019). doi: 10.1016/j. plgene.2019.100177

4. Toward Comprehensive Plant Microbiome Research. (2020). doi: 10.3389/fevo.2020.00061

5. Microbiome selection could spur next-generation plant breeding strategies. (2016). doi: 10.3389/ fmicb.2016.01971

-

Where To Buy

As a reader of the magazine, we are sure you appreciate good quality, nutrient dense food, but it isn’t always that easy to know where to buy from. We are introducing this feature to highlight those farms who are selling direct and therefore maximising their profits, not just benefitting the wider supply chains. We would hope you all will support them by buying something during the next year. If you would like your farm shop and website featured in future issues, then please drop us an email to info@directdriller.com

Ardross Farm Shop Fife

Home delivery service available in North East Fife

The Pollock family warmly welcome you to their award winning farm shop nestled in the picturesque East Neuk of Fife. Looking over the beautiful Firth of Forth, Ardross Farm Shop reconnects you with fresh, local, inspiring food from the farm and the surrounding area along with an abundance of produce from Scotland’s natural larder. Arrive to a mouth watering display of freshly picked vegetables straight from our farm. Our cabbages are so fresh they squeak, our broccoli sparkles with the morning dew and our freshly dug carrots perfume the shop with a sweet earthy smell. Freshly baked local bread tempts you further inside where our fantastic team can tantalise you with an array of specially selected products for food lovers! Using our own traditionally reared beef, fresh vegetables and other local products our kitchen is always busy and filled with the smells of homemade raspberry jam, steak pies and a variety of burgers. However it is not only our own produce that makes our selection so delicious.

Blessed with a wonderful selection of artisan products produced both locally and nationally we also stock fantastic free range eggs, rare breed bacon and local pork, world renowned venison, organic lamb and mutton, wild border game, delicious free range chickens, ready meals, British wines and beers, handmade chocolates, luxury jams and marmalades, divine puddings and ice creams to name a few. We are very proud of everything we stock and all of our products are tried and tasted by the family and many of our customers before they are included in our shop.

Court Farm Rochester

UK Wide Delivery

Specialising in traditional beef and lamb native breeds raised outdoors, Court Farm Butchery and Country Larder offers a wide range of fresh and tasty meat. Because they butcher the whole bodies, they can supply you with just about any cut you could wish for – if you don’t find what you’re looking for in the shop email them and they will endeavour to get what you’re looking for. The Country Larder stocks a selection of preserves, sauces, speciality cheeses, Wessex Mill flour, Owlet apple juice and award-winning Simply ice cream from Ashford plus local fruit and veg from David Catt & Sons, and free-range eggs from Fairseat Farm. In house they make their own pies, pasties, sausage rolls and pork scratchings plus a selection of cold deli meats. The Linghams have been farming at Court Farm for three generations. Court Farm Butchery & Country Larder is a well-known brand in North Kent since opening to the public in the 1990s.

-

Farmer Focus – Chris Hollingsworth

Harvest 2021 roundup at Hawk Mill, an East

Anglian perspective.In my first Farmer focus piece, I am writing to you about a new company which will revolutionise our farming businesses and one I have become personally involved in. It’s a company called Farmdeals (you will have probably seen the adverts) and where better to start the journey than here at the Direct Driller magazine. The fastest growing farming publication on the planet and one of the very few farming journals where you get the real story not fake news.

Agriculture is the last major industry left without an online digital trading platform, well that was until Farmdeals was born. The Farming Forum has teamed up with a software company called Future Farm. They bring to the table experienced engineers who have the knowledge and ability to build the right digital platform for our industry, that with the experience of the marketing team at the Farming Forum then we have the right structure to create a very successful online digital ordering platform. We can dramatically reduce the cost of every transaction and pass that on to our farmers. We can do this because a digital ordering platform requires considerably less labour to run it than a traditional buying group. This will reduce our costs so we can pass this on to our farmers or members with lower prices.

There will be special offers, different payment terms, price updating. Deals where the price reduces as more product is sold and the savings are passed onto you. Where the price will drop depending on the how many farmers buy. We will encourage you all to do what we call ‘milk round ‘deals. An example of this is with fuel. We set up a 36,000-litre tanker delivery direct from the refinery to a particular area (minimum order for each farm would be 6000 litres). We can offer this at a 10% discount to conventional deliveries. This will incentivise you the farmer via your Facebook, Twitter or Whats app groups to build mini buying groups to trade with us, deals within Farmdeals.

All of this is designed to bring the manufacturer closer to the farmer, reduce the links in the chain between buyer and seller, optimise the price and give the farmer (whatever his size) more power in the marketplace. This doesn’t come as a long list of messages in your voicemail or endless emails to put in your delete box but instead in one easy to use app which you can view either on your mobile from the tractor seat or in the office on the laptop.The Farmdeals platform has been carefully designed to help you make the right choices. Yes, there will be some bumps in the road as the present cumbersome and expensive framework of buying and selling is slowly dismantled and yes there will be plenty of resistance from the trade.

Farmers are traditional and not everyone is going to take to online digital ordering straight away. Some will still want to chat to their supplier and will be unwilling to complete their transaction with a couple of clicks on their mobile phone from the tractor seat. But hey, Rome was not built in a day. By now I am sure you are all thinking well good for you Chris so you are going to be making money out of your investment. Well true we are not going to do this for nothing but we all firmly believe, and this is written into the very heart and soul of the Farming Forum that we can start to disrupt agriculture’s current trading system and we can all benefit from it.

Next time a salesman rings you on your mobile or worse still drives up to your farm just think who is paying for this? Between the manufacturer and you, how many middlemen are there all taking a margin out of the transaction? Farmdeals will allow us to trade at a considerably lower cost and pass that onto you the farmer, and as we build our membership base, we will be able to command better prices for everyone. I use the word member because in effect we are an Agricultural Buying Group, but maybe not one you would recognise.

Currently there is no membership or joining fee, no levy on turnover and very small commission charges. What’s the downside? Well, the personal service will be different. Queries, questions etc will be dealt with mainly by our help/ chat lines. We will have staff available to help you, but you will be encouraged to use the online service first. Check out the web site and you will see how many products we already have, look at our prices and see how competitive we are. Currently we have Fuel, Ad blue, Oils and Greases, Fertiliser, Crop Nutrition, Agchem, Animal feed, Vet Meds, Machinery parts with many more to follow. So far, we have discussed the purchase side of Agriculture, well that’s not all we are planning to do. We started on the purchase side, but we are now building a Selling Platform and that’s where the story gets even more interesting. We want to build a much closer relationship between the farmer and the consumer.

Very important and challenging in the fresh produce business but why not? If I was a livestock farmer producing high quality grass-fed beef, I would love to link up to a chain of restaurants who will buy direct from me and yes, they will pay a premium Farming is never easy and no more so than in today’s world. Farmdeals will help you to find new ways of reducing your costs of production and selling your produce at a better price.

So come and look at what we do and sign up as a member. We are only a click away.

-

What Do You Read?

If you are like us, then you don’t know where to start when it comes to other reading apart from farming magazines.

However, there is so much information out there that can help us understand our businesses, farm better and

understand the position of non-farmers. We have listed a few more books you might find interesting, challenge the

way you currently think and help you farm better.

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures

The more we learn about fungi, the less makes sense without them. Neither plant nor animal, they are found throughout the earth, the air and our bodies. They can be microscopic, yet also account for the largest organisms ever recorded. They enabled the first life on land, can survive unprotected in space and thrive amidst nuclear radiation. In fact, nearly all life relies in some way on fungi.

These endlessly surprising organisms have no brain but can solve problems and manipulate animal behaviour with devastating precision. In giving us bread, alcohol and lifesaving medicines, fungi have shaped human history, and their psychedelic properties have recently been shown to alleviate a number of mental illnesses. Their ability to digest plastic, explosives, pesticides and crude oil is being harnessed in break-through technologies, and the discovery that they connect plants in underground networks, the ‘Wood Wide Web’, is transforming the way we understand ecosystems. Yet over ninety percent of their species remain undocumented. Entangled Life is a mind-altering journey into a spectacular and neglected world, and shows that fungi provide a key to understanding both the planet on which we live, and life itself.

The Secret Network of Nature: The Delicate Balance of All Living Things

The natural world is a web of intricate connections, many of which go unnoticed by humans. But it is these connections that maintain nature’s finely balanced equilibrium. Drawing on the latest scientific discoveries and decades of experience as a forester, Peter Wohlleben shows us how different animals, plants, rivers, rocks and weather systems cooperate, and what’s at stake when these delicate systems are unbalanced.

The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate

Are trees social beings? How do trees live? Do they feel pain or have

awareness of their surroundings?In The Hidden Life of Trees Peter Wohlleben makes the case that the forest is a social network. He draws on groundbreaking scientific discoveries to describe how trees are like human families: tree parents live together with their children, communicate with them, support them as they grow, share nutrients with those who are sick or struggling, and even warn each other of impending dangers. Wohlleben also shares his deep love of woods and forests, explaining the amazing processes of life, death and regeneration he has observed in his woodland.

A walk in the woods will never be the same again.

For the Love of Soil: Strategies to Regenerate Our Food Production Systems

Learn a roadmap to healthy soil and revitalised food systems for powerfully address these times of challenge. This book equips producers with knowledge, skills and insights to regenerate ecosystem health and grow farm/ranch profits. Learn how to:- Triage soil health and act to fast-track soil and plant healthBuild healthy resilient soil systemsDevelop a deeper understanding of microbial and mineral synergiesRead what weeds and diseases are communicating about soil and plant health-Create healthy, productive and profitable landscapes.Globally recognised soil advocate and agroecologist Nicole Masters delivers the solution to rewind the clock on this increasingly critical soil crisis in her first book, For the Love of Soil.

She argues we can no longer treat soil like dirt. Instead, we must take a soil-first approach to regenerate landscapes, restore natural cycles, and bring vitality back to ecosystems. This book translates the often complex and technical know-how of soil into more digestible terms through case studies from regenerative farmers, growers, and ranchers in Australasia and North America. Along with sharing key soil health principles and restoration tools, For the Love of Soil provides land managers with an action plan to kickstart their soil resource’s well being, no matter the scale.“For years many of us involved in regenerative agriculture have been touting the soil health – plant health – animal health – human health connection but no one has tied them all together like Nicole does in “For the love of Soil”! ” Gabe Brown, Browns Ranch, Nourished by Nature. “William Gibson once said that “the future is here – it is just not evenly distributed.” “Nicole modestly claims that the information in the book is not new thinking, but her resynthesis of the lessons she has learned and refined in collaboration with regenerative land-managers is new, and it is powerful.” Says Abe Collins, cofounder of LandStream and founder of Collins Grazing. “She lucidly shares lessons learned from the deeptopsoil futures she and her farming and ranching partners manage for and achieve.”The case studies, science and examples presented a compelling testament to the global, rapidly growing soil health movement. “These food producers are taking actions to imitate natural systems more closely,” says Masters. “… they are rewarded with more efficient nutrient, carbon, and water cycles; improved plant and animal health, nutrient density, reduced stress, and ultimately, profitability.”In spite of the challenges food producers face, Masters’ book shows even incredibly degraded landscapes can be regenerated through mimicking natural systems and focusing on the soil first. “Our global agricultural production systems are frequently at war with ecosystem health and Mother Nature,” notes Terry McCosker of Resource Consulting Services in Australia. “In this book, Nicole is declaring peace with nature and provides us with the science and guidelines to join the regenerative agriculture movement while increasing profits.”Buy this book today to take your farm or ranch to the next level!

Quality Agriculture: Conversations about Regenerative Agronomy with Innovative Scientists and Growers

An increasing number of farmers and scientists believe the foundational ideas of mainstream agronomy are incomplete and unsound. Conventional crop production ignores biology in favor of chemical interventions, leading farmers to buy inputs they don’t need. Fertilizer recommendations keep going up, pest pressure becomes more intense, pesticide applications are needed more often, and soil health continues to degrade. However, innovative growers and researchers are beginning to think differently about production agriculture systems. They have developed practices that regenerate soil and plant health and that deliver much better results than mainstream methods.

Using these principles, growers are able to decrease fertilizer applications, reduce disease and insect pressure, hold more water in the soil, improve soil health, and grow crops that are more resilient to climatic extremes, increasing farm profitability immediately. As a leading agronomist and teacher, John Kempf has implemented regenerative agricultural systems on millions of acres across many different crop types and growing regions with his team at Advancing Eco Agriculture. In Quality Agriculture, John interviews a group of growers, consultants, and scientists who describe how to think and farm differently in order to produce exceptional results in the field. Their remarkable insights will challenge you, encourage you, and inspire gratitude and joy for the rewards of working with natural systems.

A Soil Owner’s Manual: How to Restore and Maintain Soil Health

A Soil Owner’s Manual: Restoring and Maintaining Soil Health, is about restoring the capacity of your soil to perform all the functions it was intended to perform. This book is not another fanciful guide on how to continuously manipulate and amend your soil to try and keep it productive. This book will change the way you think about and manage your soil. It may even change your life. If you are interested in solving the problem of dysfunctional soil and successfully addressing the symptoms of soil erosion, water runoff, nutrient deficiencies, compaction, soil crusting, weeds, insect pests, plant diseases, and water pollution, or simply wish to grow healthy vegetables in your family garden, then this book is for you.

Soil health pioneer Jon Stika, describes in simple terms how you can bring your soil back to its full productive potential by understanding and applying the principles that built your soil in the first place. Understanding how the soil functions is critical to reducing the reliance on expensive inputs to maintain yields. Working with, instead of against, the processes that naturally govern the soil can increase profitability and restore the soil to health. Restoring soil health can proactively solve natural resource issues before regulations are imposed that will merely address the symptoms.

This book will lead you through the basic biology and guiding principles that will allow you to assess and restore your soil. It is part of a movement currently underway in agriculture that is working to restore what has been lost. A Soil Owner’s Manual: Restoring and Maintaining Soil Health will give you the opportunity to be part of this movement. Restoring soil health is restoring hope in the future of agriculture, from large farm fields and pastures, down to your own vegetable or flower garden.

-

Introduction – Issue 13

Substituting the plough, power harrow, sub-soiler and cultivator for a one-pass machine makes sense for any farm. Creating a soil environment which allows nature to do the hard work is, as we all know, beneficial to farm profitability, farming lives, greenhouse gas emissions, birds and bees. These benefits fit with the thinking of Defra minister George Eustice, the current incumbent of a job which has been one for sprinters rather than stayers.

He followed Theresa Villiers, minister for 7 months, preceded by Michael Gove (2 years 1 month), Andrea Leadsom (11 months), Liz Truss (2 years), and Owen Paterson (1 year 10 months). Gove called for the Agriculture Bill creating the slogan ‘public money for public good’, and Eustice has the task of making this happen. Though from a Cornish fruit farming family, Eustice is a politician through and through. Having served a five year stint in Defra he described the EU Common Agricultural Policy as “a basket case”, and it is clear that the move to a better system which rewards environmental work is a priority, but not straightforward.

There remains a lack of detail on what qualifies as public goods. A recent article in Politics Home magazine The House (March 9, 2021) explained ‘…post-Brexit the (UK) government wants to see sustainable, subsidy-free farming, that only rewards people financially for improving so-called ‘public goods’. This means reward for improving the environment, animal health and welfare, and reducing carbon emissions.’ Author Kate Proctor says the majority of farmers in England will see a 5% reduction in income in 2021/22. Basic Payment is being phased out and ELMs phased in.

The CLA sees a gap in the middle, which they are calling a ‘valley of death’. The newly created Sustainable Farming Incentive aims to reduce the impact. Eustice is wanting older farmers out so new blood can come in, saying we have to design future farm policies for the farmers of tomorrow. Incentives to get the oldsters out sounds logical, but has the danger of inflicting damage by loading young people with debt. Buying the farm from the older generation is far more expensive than inheriting it once they have passed on, thanks to Agricultural Property Relief. The minister appears to associate farm progress with technology and data – the province of young minds – whereas the really exciting revolution is the substitution of farming with chemicals to doing the job by biology, something that is understood by older and young farmers to an equal degree. Eustice (49) must be careful not to become too ageist.

Defra has yet to set practical goals and outcomes; has yet to determine a farmer extension or education policy; remains unclear about cropping and many other issues that farmers have to decide on. Matching these to the environmental outcomes set for the industry to meet targets needs the involvement of many different stakeholders, and I include publications such as Direct Driller which I believe is one of the most important environmental publications in Britain. The value of diversity and the dangers of a one-size-fits-all farming policy to food production need remembering. The Covid pandemic shows that biblical events are ready to strike. These might include the potato famine, the failure of the groundnut scheme in East Africa or collective farming in Russia and its satellites. The variability of UK farming methods, and the choice of individual farmers to do what they see best, is something to be applauded and maintained.

-

Work from Home

We have featured articles on many different types of robots that will at some point influence the way we farm, but have the simple wins in the arable world have been ignored? Possibly because they don’t benefit the trade, maybe they are simply a bad idea or maybe a bit of both. However, if the pandemic has shown us one thing, working from home is possible for a lot of industries. But the agronomists among us have not had this luxury.

They, like the farmers, still have to get dressed every day and drive somewhere. Apparently, nothing can compare to actually walking a field. Except for the fact I am being told by every robot manufacturer and drone app company out there, that it can. Why are companies so slow to offer you a digital agronomist? A cheaper version of a walked agronomist, who you have to send the pictures and information to and they help you make decisions.

My feeling is that it’s a liability problem.

Someone is responsible for whether the crops in a field grow or not. If an agronomist is walking a field, they can make the decision to turn left or right based on what they are seeing right now. They take on the responsibility. But if they aren’t there, someone else has to feed them the information. Can they really zoom into one of 500 pictures you send them every week and do the same job. I’m not sure they can and even if it was possible, who knows if they have been sent the “right” pictures for analysis.

The question then moves onto, who is at fault when something goes wrong. Do farmers really want the extra risk of something going wrong just to save a few £s per hectare walking fee? Agronomists, keep you wellies at the ready, we still need you on farm!

-

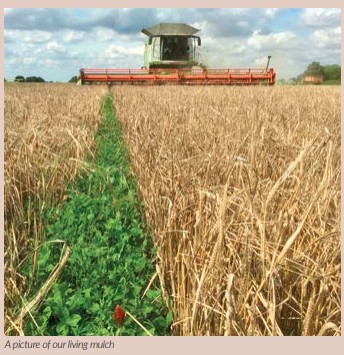

Living Mulches For Sustainable Cropping Systems: A Step Towards ‘Regenerative Organic’ Agriculture In The UK?

Written by Dominic Amos, Crops Researcher at the Organic Research Centre

As based on information found on Agricology (www.agricology.co.uk)

Reducing tillage and chemical inputs can be beneficial for soil and the environment, so could a permanent clover understorey acting as a ‘living mulch’, moving towards a perennial soil cover, offer a practical solution to reducing inputs and having more sustainable cropping systems?This is the question being investigated by a group of arable farmers attempting to implement the system for input reduction through an Innovative Farmers Field Lab. Inputs in this case could be agrochemicals and fertilisers or tillage and diesel, depending on the current farming system. These are the two starting points of the group who are either already practicing long term conventional no-till looking to reduce chemical inputs or established organic farmers looking to reduce tillage. There is an imperative from both perspectives but whilst both farming systems can learn from each other, the challenges for each of making an alternative system work are quite different due to the respective starting points.

What is a living mulch?

A living mulch (LM) system includes aspects of several common farming practices and concepts such as cover cropping, intercropping, undersowing, and mulching, with the system building upon these approaches with full integration as a cropping system. In practical terms it requires the establishment of a perennial forage legume to provide protection for the soil as a (semi-)permanent ground cover common to perennial cropping systems such as top fruit or viticulture. It is rarely used in annual cropping systems due to the competition with the cash crop so the question is, is it compatible with annual arable cropping? The LM approach differs from the well-known organic reduced tillage systems with the roller crimper pioneered by Rodale where the idea is to terminate high biomass cover crops to provide a dead mulch that helps suppress weeds for establishing cash crops. In truth this system relies on certain climatic conditions generally not experienced in the UK.

Services and benefits

The LM system can be expected to deliver a number of key ecological services to the agroecosystem including nitrogen (N) accumulation, weed suppression, enhanced soil physical characteristics (and trafficability), soil protection, catch cropping function, self-regulation of pests and disease, increased soil fertility and increased biological diversity. At this stage it is also worth considering that many organic farms already have weeds that provide some of the ecosystem services but with less control over species, so the mulch could be thought of as a ’designated weed.’¹

The two key services that need to be delivered for a LM system to best contribute to agricultural productivity are weed control and N supply.Living mulches offer a potential alternative and sustainable strategy for these two provisions, although the amount of N made available for the cash crop and level of weed control will be greatly influenced by management and by the season. Conventional notill systems may require supplemental N fertiliser to maintain crop yields. These two services offer an insight into the complexity of the system and the trade-offs (not necessarily unavoidable). There is a strong correlation between the mulch biomass and weed suppression and N accumulation services but high biomass will offer stronger competition against the cash crop.

This management balancing act between cash and cover crop growth throughout the season is the fundamental challenge to a working LM system – in order to harness the benefits of this permanent cover whilst limiting the risks to productivity. If enhanced soil health, increased biodiversity (above and below ground) and reduced emissions can also be delivered, then a more sustainable and resilient farming system is the prize on offer. There is a word of warning at this point since much of the research already conducted in this area including recent work at Stockbridge Technology Centre through the DIVERSify and TRUE projects demonstrate large and potentially unsatisfactory grain yield losses from arable LM systems that will require careful thought and management to make successful.

Enhancing beneficial interactions and managing competition

The ecological concepts that underpin the cereal-forage legume system are known as niche complementarity and facilitation and the system works on the principle of functional diversity. In theory this means the two ‘parts’ of the system work in harmony but in practice, particularly from the organic perspective, making the system work has proved elusive. This is a complex issue but a key factor is the interactions of the cash and the cover crop, and the ability to manage and manipulate the competitive advantage of the cereal. In fact, from an agroecological perspective, boosting the cash crop and weakening the cover crop at key times in the growing season is a real challenge especially since, as previously mentioned, weakening the mulch actually contradicts its key service provisions. Small doses of N fertiliser and herbicides can selectively weaken the clover and hand the competitive advantage to the cereal but of course these options are unavailable for organic farmers.

Farmer-led trials with Innovative Farmers

There are several areas that are being explored by farmers through the field lab:

1. Mulch species and establishment

2. Cash crop species and establishment

3. Mulch management (both externally and in crop)

Mulch and crop species selection

Different combinations of approaches are being tested with the farmers – utilising their knowledge of the context of their farms and systems and taking wider considerations into account to choose the most appropriate options for them. This will facilitate the peer to peer exchange and progress on living mulch best practice. In the field lab trials the farmers have used a mix of wild white and smallmedium leaf clover recommended by Cotswold Seeds, that has been selected to remain prostrate and provide persistence but with limited longer term competition against the crop. The clovers were established through undersowing into cereal crops in spring 2020.

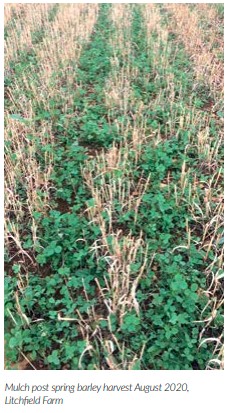

Direct drilling cereal crops into the pre-established stand of clover took place last October with winter oats and rye selected for their competitive abilities. How and when, or even if, to manage the mulch is a key question being explored. There are opportunities to mow or graze before drilling the cash crop, or even during the foundation phase of cereal growth in the late winter. One of the most interesting questions is whether the mulch needs to be selectively managed later during the growing season and how this might be done? An option being considered is inter-row mowing, though commercial equipment is not yet available.

In conclusion

This fine balance of managing and manipulating the dynamics of a cash and cover crop to the advantage of the cash crop whilst maximising the services from the cover crop is what in the end will determine the successful implementation of what is on paper a sustainable and resilient way to farm the land – albeit one that will require a system redesign approach. In the end the system will rely on the knowledge and ingenuity of the farmers and the peer to peer learning to turn the theory into successful practice.

Agricology is an independent collaboration of over 40 of the UK’s leading farming organisations sharing ideas on sustainable farming practices. We feature farmers working with natural processes to enhance their farming system, and have a wide range of farmer videos on our YouTube page. We also share the latest scientific learnings on agroecology with the farming community from our network of researchers. Our website hosts over 400 articles on different agroecological practices. Subscribe to the newsletter or follow us on social media @agricology to keep up to date and share your questions and experiences with the Agricology community.

-

Where There’s Muck There’s Brass!!

Written by Jon Williams from www.thesoilexpert.co.uk

An old adage of farming practice we need to pay attention to with our management of our slurry and manures for the benefit of the environment and our farm business.

With increasing attention focused on the environmental impact of food production methods currently in practice and the industrialisation of agriculture via the dependency on this development from synthetic fertilisers and chemical cocktails which can be considered as a chemical experiment, it is becoming increasingly clear that this form of food production is resulting in depleted soils, of soil life and nutrients with the result that the food produced no longer has the nutrient density or health benefits gained from a more balanced living soil system more in harmony with nature.

The current industrial model of agriculture must take a new more holistic approach considering not just the short term gains but also the longer-term impacts of such methods of production and one way to assist in this shift is to change our attitude toward slurry and manure, transforming this from a waste product into one that is an asset. The good news is that Governments are prepared to back this with financial incentives under the heading of providing “Public Goods”

The science of slurry and manure

To achieve the best outcome an understanding of the science of slurry and manure is useful and this combined with it’s impact on the soil when it is applied in different forms such as anaerobic or aerobic or fermented products.

Slurry

Anaerobic digestate or slurry from a crusted or covered pit will be anaerobic and will have more volatile gases present such as Nitrous oxide, Methane, Ammonia and Hydrogen Sulphide and to overcome the immediate environmental impact of these gases it is suggested that they must be injected into the soil to reduce the impact of these gasses in the air, some of which are being blamed for creating particulate matter damaging Human lung tissue. All injection of slurries must be done when soil conditions are such that they are not holding water which will result in further damage to soil life and also soil structure.

However there is a more serious long term implication when such a product is injected into soil. Being anaerobic the pH of Digestate in particular is above 8 (ref Wrap digestate and compost use in agriculture Feb 2016) and so the product is caustic and is detrimental to soil life as it burns worms which happen to like to live in an aerobic soil and so they take a hit but can get out of the way when injected in slots.

The overall impact is that the soil is flooded with available ammonia and there is a flush of Nitrogen similar to when large amounts of fertiliser Nitrogen is applied and Rothamstead have just released the results of 40 years of research showing that the more available N that is applied to soil the more it distorts the genetic expression of soil organisms. (ref Andrew W Neal) So the overall impact of anaerobic digestate or slurry from a crusted and untreated or covered store has a negative effect resulting in the soil becoming more dependent on brought in synthetic nutrients as most of the Nitrogen is immediately available.

One alternative to this is to render the slurry to being aerobic and this can be achieved in several ways with huge benefits to the environment as well as to soil life. Firstly let’s look at what is the product we are dealing with and to understand how to manage it for our best advantage and to have the least impact on the environment. Slurry generally has a low fibre content and a high Nitrogen to Carbon ratio and is bacteria dominated with little fungi present and so in that respect it is an imbalanced product as far as the soil is concerned, however we have to make the best use of it.

The nitrogen content can vary according to the amount of protein fed to the stock producing the slurry because livestock are fairly inefficient at converting protein into meat or milk and so the higher the protein diet can produce a higher value slurry and it is therefore more worthwhile to invest in stabilising the nutrients held within that particular slurry.

One of the amendments that can be used to retain this value in our slurry is to render the product to become aerobic and this can be achieved in several ways, such as a mechanical bubbler, or by adding a catalyst such as Plocher and the result of these amendments is that as the slurry becomes aerobic the pH is dropped towards neutral with the aerobic bugs creating Carbonic acid which in turn stabilises Ammonium which becomes available for plant use in a similar form as comes from fertiliser. However not all the nitrogen is in this available form as there is a portion that is retained as Organic Nitrogen as the slurry has become a stable product and is now not breaking down further as it would in a digester. The organic Nitrogen is slowly released during the months following the application and so there is not the flush of available Nitrogen as seen from Anaerobic digestate and the plant is fed in a more natural way which can have the effect of reducing the incidence of disease and better performance if conditions become dry.

Other methods of lowering the pH of slurry are being carried out with the addition of sulphuric acid which does stabilise the nutrients via the same process of lowering the pH of the slurry but does not render the slurry to being aerobic and of course there is the health and safety issues of handling and applying such a product and its corrosive nature damaging concrete slats and retaining wall.

However there is a relatively new method of lowering the pH from about 7.2 to 6.8 which is done by the addition of” Effective Microorganisms” which encourages a fermentation of the slurry. This concept was developed in Japan by a Professor Higa in 1982 who coined the term “Effective Micro-organisms” when he discovered the mix of 80 microbes which work synergistically to ferment organic matter retaining the nutrients in a stable form. The fermentation actually pre-digests the organic matter making it immediately available to the soil organisms and thus to the plants.

This product can be used with a covered slurry pit which I understand is the proposal for management of slurry stores in England. E.M. is based on the principal of anaerobic fermentation and by lowering the pH, can retain the value of the nutrients within the slurry which when applied to the soil is already in a more mature form which allows the soil organisms to utilise it without using a lot of energy and there is no loss of volatile gasses into the environment. This treated product might no longer mean that you will be required to inject it into the soil which reduces the fossil fuel use of slurry application as well as wear and tare on machinery.

Manure Management.

Having a different Nitrogen to Carbon ratio this product has a higher fibre level and therefore is more conducive to the establishment of a more balanced product enhancing both the Bacteria and the Fungi within the product and consequently when applied to the soil creating a more balanced soil. Currently on most farms this product is not amended in any way and under the proposed new legislation may need to be incorporated into soil with 24 hours of application. This of itself has an environmental impact by the very nature of ploughing it in there will be a further release of CO2 into the atmosphere but the aim of this protocol I suggest is to reduce the ammonia going off into the environment thus lowering its potential impact on Human health.

So from this we can assume that untreated manure releases volatile gasses including Ammonia and that there is considerable potential benefit in stabilising those nutrients. Most farms still leave manure in a heap outdoors and un covered releasing volatile gasses and allowing nutrient run-off, and even if an element of aerobic composting is carried out there is a further release of CO2 into the atmosphere with considerable losses. Therefore the way we currently manage manure needs to be considered.

These issues can all be dealt with by treating the manure with Effective Micro-organisms, known as Bokashi, which again ferments the manure stabilising the valuable nutrients including the ammonia and so the need for ploughing after application will not be necessary and manure application can be carried out on Min -tilled soils which will have multiple environmental benefits, retaining carbon as well as enhancing soil life and crop performance.

The product can be applied to the manure as it builds up in the sheds layering it by spraying it on the fresh bedding when added and the animals will tread it in creating an anaerobic bed but stabilising the Ammonia reducing it’s potential impact on animals within the sheds. Alternatively the sheds can be emptied and as the pile builds up the product can be applied in layers and then covered with a silage sheet for the fermentation to take place which is completed within 6 to 8 weeks leaving a mature product which will be soon converted into soil as it is quickly utilised by the soil life. This having a further benefit in feeding the soil Micro-Biome with a balanced product having both beneficial bacteria and fungi present and so the soil becomes less reliant for cropping with synthetic fertilisers and plants are less stressed with the potential of reduced disease.

An added benefit is having more product to spread on the land because the losses are dramatically reduced with no Co2 going off into the atmosphere during the process of maturation and there is more carbon entering the soil thus enhancing the nutrient and water holding capacity of the soil as well as achieving greater Carbon sequestration, a “Public Good.”

The micro-organisms in Bokashi can be considered as the new meaning of culture in the word agriculture and is already used by 75% of all Dutch farmers and I see no reason why it cannot achieve similar levels of use here in the UK. So a mind shift in thinking and a new attitude towards slurry and manure can result is a win, win situation both for the environment and the farmer.

Available from Agriton Ltd.

-

When The Medicine Feeds The Problem

Do synthetic fertilisers and pesticides exacerbate pest and disease threats? A session at the Oxford Real Farming Conference looked at the science behind the claim

Written by Mike Abram

The use of synthetic nitrogen fertilisers is increasingly under the microscope, driven mostly by its impact on the environment and as a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions on arable farms. But presentations at the Oxford Real Farming Conference also pointed how its use, and that of pesticides, might be exacerbating pest and disease problems by enhancing the nutritional quality of crops for those pests and pathogens. Nitrogen is the nutrient required in the highest quantities for plants, and was vital for crop growth and development, explained Daisy Martinez, a researcher at the University of Edinburgh.

“Plants take up nitrogen from the soil, and use it to synthesise amino acids – small, molecular building blocks – and then use it to build proteins. Proteins are the stuff of life alongside carbohydrates.”

But when the crop was flooded with too much soluble nitrogen, in the form of synthetic fertiliser, the concentration of amino acids expanded faster than the plant could make proteins, she said.

“So the plant is rich in amino acids, which are valuable nutrient sources for pests and pathogens. It’s like saying welcome to the banquet.”

A literature review of scientific papers found some insect pests laid more eggs on crops fertilised with high nitrogen rates, larvae developed more rapidly to a larger size and were more likely to survive and reproduce, she said.

“In the literature we found many examples of significantly denser populations of insect pests fertilised with high rates of nitrogen fertiliser compared with lower rates.”

Similar was true of fungal and bacterial pathogens, where crop disease severity measured by things like microbial colony-density, disease lesion area or spore production, increased where nitrogen was used at high rates, she said.

“These findings support the idea that intensive fertilisation with synthetic freely available nitrogen feed the problem with pest or pathogen damage by enriching the quality of our crops through the availability of nutrition.”

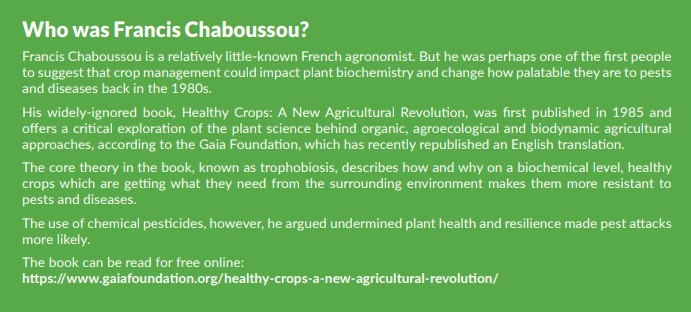

These findings supported the conclusions of a relatively littleknown French agronomist Francis Chaboussou (1908 – 1985).

But there was more to the story as just as humans have defences against diseases, so do plants, she said. These ranged from physical defences, such as waxy protected surface on leaves or strengthened cell walls, to producing defensive chemicals.

“Some of these chemicals are toxic and kill the pest or pathogen outright, while others make the crop less palatable, so the crop is not worth eating or impossible for the nutrients to be absorbed by the pathogen or pest.”

The chemicals could be split into two broad groups – nitrogen-containing or carbon-based compounds, she said. “The natural production of these chemicals can be enhanced or suppressed in response to nitrogen fertilisation.

“High nitrogen availability typically decreased production of the carbonbased defences, while stimulating the production of nitrogen-based defences. “But whether that is good or bad for the crop depends on the context, and on the crop. There are many of these compounds, and particular chemicals can be more or less crucial in different crops. “And it gets even more complicated as the pests or pathogens can be more or less sensitive to these chemicals as well so you might get an insect that is really deterred by one chemical but isn’t sensitive to another. It’s just a really complicated area,” she said. “But the main message is that nitrogen fertilisation doesn’t only just affect the crop’s nutritional quality, and therefore their susceptibility to pests and pathogens, it also affects their defences. “It is not possible to say more N is good or bad for defence, it depends on context, but it is an area that needs more research,” she concluded.

Do pesticides also enhance the nutritional quality of crops for pests and pathogens?

The research team also looked at whether applying pesticides also enhanced the nutritional quality of crops for their pests and pathogens. “This is a little paradoxical – pesticides are applied to crops to suppress, deter or kill pests or pathogens, and should be minimally harmful to crops in the process,” Daisy said.