If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Farmer Focus – Andrew Jackson

September 2024

Another year has passed and although I am without doubt a bit older, hopefully I am a little wiser from all the errors that I have made. We have tried to devise a rotation based around predominantly first wheats, interrupted with break crops of grass seed (down for two and a half years and grazed in the winter periods), OSR and this year for the first time, spring beans and BOATS (spring oats sown alongside spring beans). Although we were confronted with a wet autumn, we have a low grass weed burden which enabled us to press on with the autumn drilling, we used our own seed, a ten-way soft wheat blend and took it straight out of the shed (rightly or wrongly). Our six metre Horizon drill, operated by my daughter Anna went well and although I would have liked to have tried to place some liquid biologicals alongside the seed, last autumn did not allow the time to be trialling.

We successfully sowed all our seed before the heavens really opened. Throughout the wet winter period, I was asked whether, because we had direct drilled and not cultivated to take out any compaction, then surely our fields must be full of puddles, the answer was ,there were no puddles apart from one or two parts of historically compacted tramlines on better bodied soils. This free draining soil, represented the results of four years drilling and levelling the fields with a Sumo DTS, followed by four years using a direct drill, no cultivations, just putting faith in the system.

Anna and to a lesser extent myself, appear in the film Six Inches of Soil. This had been three years in the making and we attended the first viewing in December in Cambridge.

We attended the first public viewing at the Oxford Real Farming Conference. Prior to the viewing we enjoyed a beer with Tim Parton, this was shortly before his horrific accident. I am sure that you will all join me in wishing Tim a speedy recovery in his adjustment back to his farming life.

We also had a film viewing in our play barn at the Pink Pig Farm. This was for me particularly nerve racking because my farm and its system was being judged by many of my farming friends on the big screen. I sat at the back and knowing that I would be answering questions on a panel after the film, I filled myself with Dutch courage maybe excessively! Needless to say, I have not been asked to sit on a post film panel since. Anna and I have attended other viewings at York and John Pawsey’s farm in Suffolk, all the viewings were well received and followed up by a plethora of questions for the panel.

We finally completed the foliar nitrogen plant. Within the plant we have a twenty-five thousand litre tank which can be filled with rainwater to the required level and then urea and sulphur are added to a specified recipe, the contents of the tank are agitated for twelve to twenty-four hours, depending on the ambient temperature, then the finished product can be pumped into one of three twenty thousand litre storage tanks.

I have an eighty thousand litre rainwater tank sited outside the building to capture rainwater and since the recipe specifies soft water, I was particularly concerned that the collection from the gutters would not supply enough. I need not have worried, after that wet winter, I have even had to fill one of my fertiliser storage tanks with the precious, soft rainwater. I should add that we had to bund the whole building and simultaneously we relocated our chemical store to enable the whole mixing and storage operation to take place under cover. We would like to thank Anglian Water for a grant which contributed to the cost.

On the day of foliar fertiliser application, we then add in biologicals such as Fish hydrolysate, molasses and Hutchinson’s Humagro, all is applied at one hundred litres per hectare which means that we can cover some ground quickly. No scorch was apparent; however, we did endeavour to apply early in the mornings. The theory of applying foliar nitrogen as opposed to soil applied nitrogen is that it is up to four times more efficient, therefore allowing for a reduction in application rates accompanied by financial savings of home mixing and using less product. Amendments, such as magnesium and manganese can be added when sap tests dictate. The wheats crops were also treated with Sycon as a fungicide replacement, eventually the disease pressure was so high that we had to apply a normal fungicide in the latter growth stages.

The spring beans had always been planned and were grown on contract for seed for Limagrain, for many farmers spring beans were sown because of the wet autumn and winter. We also tried BOATS, apart from one trace element application, they received no fertiliser, herbicide, or fungicide products and may be suitable for a premium market outlet. Following a three-year break of two years of grass and one year of OSR or Beans, we were able to grow a crop of Basic Typhoon seed for Limagrain, but we requested no seed dressing, this action also allowed us to spread our risk of growing 100% home saved seed.

I attended Groundswell with the aim of investigating three topics: adding value to my grain, robotic camera guided hoes and Exlana sheep. I came away having decided that I would try Wildfarmed wheat, if its happening on Clarkson’s farm ,then it probably should happen on mine. Although the SFI pay reasonable rewards for interrow hoeing and there are grants to buy the hoe, two things are holding me back, firstly if I could achieve an understory of clover or indeed lucerne, then it may not be easy or desirable to inter row hoe and secondly, I cannot believe the price of the hoes. Have they pumped up the price on the back of the government incentives? Every year our sheep enterprise is confronted with fly strike, shearing costs and bags of wool with very low value. At Groundswell I visited the Exlana stand and concluded that going forward we should run wool shedding sheep , such as Exlanas, I just must convince my daughter.

By completing two Carbon Calculators, I have come out just about carbon neutral and consequently I have been approached to become a Climate demonstration farm, I attended a webinar in relation to this which was presenting thoughts and theories from lecturers from a selection of European Universities. What they said could have been straight out of a presentation from thirty years ago. It’s so concerning that the educational institutions do not appear to have moved with the times.

More encouraging was an excellent conference at Downing College Cambridge, it was organised by a group of trusts, being predominantly driven by members of the Sainsbury family, who are themselves farming regeneratively. The conference had the aim of creating more collaboration between the scientists (educational institutes), the farmers and the city institutions who might fund research on our behalf. Once again, the scientific community only like to measure one or two variables in a single trial. I stood up and explained the multitude of changes which have taken place on my farm in a relatively short period of time, I fear that I am acting on hope and blind faith, using and adapting research from other countries around the world, in the absence of any meaningful research in the UK. One very positive presentation came from Ruth Wade who, in conjunction with a cluster of Yorkshire farmers is carrying out some more relative trials work at Leeds University, albeit she is about to run out of funding.

After years of growing Birds Eye peas in a six-year rotation, our farm has become pea sick with foot rot, regrettably the system was not as sustainable as we thought, or was it the decades of ploughing?. We now rent land for peas and this year, due to the weather conditions and the fact that I refused to plough, (instead I had Sumo trio ’ed the field, leaving some surface trash), I was asked to direct drill the peas, this went reasonably well considering that direct drills do not really like cultivated soils. However, my field was hit by every pigeon in the territory and given that margins are quite tight on rented land, after forty years of being a Birds Eye pea grower, I have given notice to quit growing peas. I also had poor OSR yields, part of this might have been seasonal, however I do believe that OSR is quite a weak rooter, and I have struggled to get outstanding OSR crops from direct drilling, so out of the window goes the OSR also.

For years I have operated Gatekeeper, and I guess that I have learnt to live with its clunkiness, Anna will not work with Gatekeeper, she said that it is back in the ark, so we are changing to the Hutchinson crop recording package Omnia, and she will be in the driving seat for that product.

We have tried various actions with our direct drilling to establish an herbal ley into existing grassland, all have failed, so this year we have had to hire/borrow a plough and two of my children were taught the acquired skill of how to plough. The herbal ley seed was then sown into the blacked over soil and we eagerly await emergence.

I have been in the SFI pilot which is coming to an end soon and so I have been reviewing the options of the 2024 SFI Scheme. It may come as no surprise that being a regenerative farmer, I will be able to tick so many more boxes than my conventional neighbours. It seems likely that the Wildfarmed area may be eligible for the low input cereal option, on those grounds BOATS could also qualify, therefore enabling BOATS to become a viable break crop, which may replace OSR in the rotation.

Our wedding barn diversification has gone well for two summer seasons, which is just as well because both of my daughters have announced their engagements this summer. Carl and Anna announced their engagement in May, on the weekend of the engagement, it had been suggested by Claire Mackenzie that Anna might want to go to London to promote the Six Inches of Soil book at a book signing. The event would take place alongside Gabe Brown, who would be in the UK, not only to promote his book, but on other business. I explained to Claire that I had prior knowledge of Anna’s forthcoming engagement, and that Anna would not be available to go to London. A plan was then hatched (not by me), to drive Gabe straight from Heathrow to Scunthorpe, with the intention of giving Anna a second surprise for that weekend. This cunning plan was implemented and we hosted Gabe and his colleagues to a brief farm walk and a Barbeque, on which turned out to be, one of the most idyllic of May days that you could possibly imagine, Gabe might have been a bit jet lagged, but wow, who would have told me back in 2016, when I read Dirt to Soil, that I would be entertaining its author in my garden, eight years later?

-

Getting emissions down in a measured way

Written by Rob Nightingale from Frontier

“Yield is king!” This was a tag line in farming throughout my career as a farm manager and agronomist. Interestingly, now as a technical sustainability specialist, it’s a phrase finding resurgence again.

At times in our history it has probably been more pertinent than others, for example during the second World War when the UK was cut off from imports and the onus on domestic production and supply was significant. Since then, however, conversations about yield have typically centred around profitability.

Being profitable has often meant producing as much yield as possible from a piece of land, ideally with minimal investment to ensure the best returns. However, in the last 30 years, UK wheat yields have plateaued and rather than reaching for the highest, the focus shifted to aiming for the optimum.

Rob Nightingale This was the case when I started as a farm manager and continued as an agronomist – matching inputs to outputs and keeping the cost of production per tonne in mind. Since moving to my technical sustainability role, yield is indeed still king, but the narrative around what that looks like in today’s agricultural landscape has shifted again.

But, why? To put it simply, in the UK we have some of the best yielding land in the world. The global winter wheat average for the last five years was 3.53t/ha, whereas the UK average for the same period was 8.05t/ha. If we consider that comparatively, you could say that every hectare in the UK yields 2.2 times more than the global standard.

Of course, this doesn’t mean we should farm the entirety of the UK. We have incredible flora and fauna here and, importantly, we rely on that biodiversity to sustain and enhance the farmed environment we depend on. Instead, where crops are being grown, the priority now is to optimise those areas to deliver the highest yield with the lowest environmental impact, ensuring sustainable, resilient farming systems that delivers for the long term.

With the benefit of hindsight (it is 20:20 after all), the ‘optimum yield’ can seem clear, but basing the experience of one season on the next is never a guarantee. Instead, it’s about ongoing monitoring to understand what the yield potential truly is, using those insights to better understand what the picture could look like next time.

Reviewing crop input strategies is an important part of this and we’re continually investigating solutions that support growers to adopt approaches based on applying the right amount in the right place; matching crop need.

If we look at nitrogen requirements in wheat for example, calculating optimum applications might seem a relatively straightforward exercise on paper. A crop of wheat’s offtake is the amount of nitrogen removed from the field, otherwise expressed as yield (dry matter) x grain nitrogen (%). For example:

8t/ha yield x 11% grain protein = 6800kg/ha x 1.93% nitrogen = 131kg grain nitrogen offtake.

Once we have this figure we then need to account for the nitrogen taken up by the crop to produce roots, stems and leaves that doesn’t get transferred into the grain by harvest.

The proportion of nitrogen in grain is typically around 68%, so we divide the grain nitrogen offtake by 68% to get the total nitrogen uptake. For example:

131kg grain nitrogen offtake ÷ 68% = 193kg/ha total nitrogen uptake.

If we think back to the five-year UK average of just over 8t/ha at 11% protein, based on the above calculations we therefore need the crop to take up 193kgN/ha from all sources. Simple, right? Not quite. How we get enough nitrogen there in the first place is key.

To maintain or even improve the yields we see in the UK, it’s important to create conditions where adequate nitrogen can be taken up by the plant to support grain production. The challenge our industry has is how to achieve these optimum levels.

Today, agriculture relies on mineral fertilisers as its predominant nitrogen source; with nitrogen produced by the Haber-Bosch process estimated to support food production for nearly half the world’s population.

However, with a growing focus on the sustainability credentials and carbon footprint of food production, exploration into ‘greener’ fertilisers is growing. Of course, moving away from the ‘norm’ isn’t a process that can happen overnight without there being wider impacts on crop production.

It’s therefore important to look at how to make the most of current practices too. For example, setting rotations up to get the maximum from soil nitrogen supply for those crops with a higher nitrogen demand. This could be along the lines of using grain legumes i.e. incorporating peas and beans, or even approaches such as undersowing with clover to help retain and increase nutrients for future crops.

Measuring the amount of available nitrogen in the soil provides a better understanding of how much additional nitrogen is needed to supply the crop too. Assessing biomass through precision services such as SOYL provides insight into nutrient levels across the farm and individual fields, supporting more targeted, variable applications with nitrogen doses subsequently adjusted higher or lower to suit demand.

At the end of the season, the results from in-field grain analysis and harvest sampling provide the equivalent of a ‘report card’, detailing how well a crop’s needs were met and therefore what worked and what needs reviewing. This data combined with the amount of applied nitrogen can help calculate a nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) score – a great measure for understanding how and where inputs may need adapting.

This calculation can provide a lot of insight into where nitrogen has been used and the yield potential of a field. For example, feed wheat’s optimum yield is seen when grain protein is at 10.8% protein. Using that as a benchmark, it can help in identifying whether nitrogen has been over or under-applied, if there is an issue with crop uptake or if the yield is lower than the potential of the field in question. If we look again at the UK vs. global average, any ‘lost’ yield potential is therefore a waste.

In my current role looking at the sustainability of farming systems, I spend a lot of time discussing production data and how to interpret the insights gathered during the process of growing a crop. This includes fertiliser product use, tillage type and yield principally, but reporting can be broadened to encompass much more, such as grain quality for example.

By collating this information, powerful data sets can be constructed and the insights gathered can support all parties of a supply chain, from farmer to grain processer, to continually advance the future of food production and make the right moves towards a more sustainable future. I always stress too that it isn’t the data in and of itself that is ‘valuable’, it’s the story it tells, the understandings it can generate at scale and the time and effort taken to do that.

Truly, I believe that UK farming is some of the best in the world, and it is intrinsic to supporting future improvements to our environment. There are a lot of positives to share about our industry and the ever-evolving science, innovation and forward-thinking approaches so many adopt and explore. Recording more of this better equips us to share this work even more widely, including to those buying the products derived from this work.

Yield is king when we’re talking about sustainability. Getting more from less in the right ways drives all of us to be more efficient. This is not just a discussion around land sparing vs. land sharing, it’s about striking the right balance between food production and the environment, doing the right things in the right places and for the right reasons. The story of how and why we do it is one we can all help to capture – not only can we all learn from it, but we can share that knowledge (and pride) with so many others too.

-

The Time is Now: Why It’s the Perfect Moment to Get Behind Regenerative Agriculture

Written by Angus Chalmers, Managing Director of RDP Comms

The World Economic Forum defines regenerative agriculture as ‘a way of farming that focuses on soil health.’ This is its key premise, using nature’s recipe, soil, to achieve productivity goals rather than relying on ever more complex manmade interventions. The last agricultural revolution was transformational for the wellbeing of the world’s population, but now we understand more about the impact of conventional farming, there is a growing realisation that we need to work more closely with mother nature’s natural processes.

Regenerative agriculture allows us to do this. As a more holistic approach to farming, it encompasses the whole eco system, enables us to work with and enhance what nature can deliver, and has the potential to provide a balanced and more efficient way of producing food. However, let us not forget that data, knowledge, and precision agriculture will be just as important in a regen world as it has always been. We will just be doing it as part of a more sustainable food system.

Industry events we have attended so far this year have demonstrated just how much momentum there is behind the regenerative movement. At Groundswell, Cereals, and a visit to an AHDB monitor farm, there has been a focus on different regenerative techniques and approaches. This illustrated just how broad a church regenerative agriculture is and therein lies its beauty. The reason it’s become such a strong movement is that it does not try to force farmers to follow a blueprint. It is inclusive, farmers can enter at multiple levels, starting simply by making a few minor changes or adopting wholescale system change. Ironically many farmers already practice some form of regenerative agriculture, but just do not recognise it as such.

The strong message of the regenerative ‘brand’

If we consider the regenerative ‘brand’ as a representation of UK agriculture, we need to be careful about how it is developed. How can we nurture the brand to cut through misinformation, particularly given that it is not perfect science and consumer understanding is lacking?

Recent research from EIT Food (European Institute for Innovation and Technology) looked at consumer perceptions of regenerative agriculture. It found that consumers do not think much about the different agricultural methods used to produce their food, but they are concerned about chemical use and food quality. They also perceive that food grown in a regenerative system is healthier, nutritious, and tastes better mainly because fewer chemicals and pesticides are used in production. There is also a wider recognition that regenerative agriculture is aligned to a sustainable food future in a greater way than conventional farming.

For both consumers and farmers, the regenerative agriculture brand has a strong message. It delivers nutritious food, and whether tastier or not is subjective, but it enhances soil health. Ultimately this delivers healthier crops requiring less intervention to help them grow and ward off pests and disease as they are extracting much of what they need from the soil. Mother nature’s recipe, when healthy and in good heart is more effective and has the potential to deliver greater returns to farmers.

A wider opportunity for society

The time is right for us as agriculturalists to back the regenerative movement, but in my mind the far bigger prize is the opportunity this represents for UK agriculture to engage with the rest of society and rally behind a brand which is already seen as positive. Rather than occupying different camps, demonising conventional farming for being too industrial, or organic farming for being expensive and low output, we need to embrace the regenerative movement, in all its guises. Encourage its uptake and development and invest in its future.

We need to recognise that this brand has the opportunity to penetrate right through to the consumer. Let us ask ourselves the question; how do we grow this positive position? What we must not do is confuse and divide, ‘my regenerative method is better than yours.’ Our great industry tends to shoot itself in the foot when our eyes are too firmly faced inwards, let us look outwards at our industry’s reputation in the eyes of the end consumer, we have a remarkable story to tell. By all means, if a certain approach provides a unique selling point, then make the most of it, enhance your brand and marketing approach but let us not damage the industry’s wider reputation.

In this age of instant communication and social media, it does not take long to spread messaging that is wildly incorrect, and that people take as gospel. There is no right way to adopt regenerative agriculture, we still have so much to learn, so we must not be too possessive, but be embracing for the good of UK agriculture.

I am under no illusion, however that there is a challenge in developing the regenerative brand, as it currently possesses so many definitions. A tighter definition would reduce the chances of damaging misinterpretation and enable faster growth and wider acceptance. However, the existence of this wide definition is exactly the reason regenerative agriculture has demonstrated such dramatic momentum. Is there is a place for an umbrella brand that remains a broad church, with more nuanced and focussed approaches developing their unique positions in support of the wider movement?

The regenerative movement is gaining momentum, in all its many guises, and combined with innovative technology and precision agriculture will increase the chance we have of delivering the food we need whilst enhancing soil health, biodiversity and nature reconstruction. Regenerative agriculture might not be perfect, but it speaks to many of the challenges we are facing and above all provides cut through to our most important judge, the consumer, so let us build on this opportunity.

-

Beyond the barrel: the unique process behind the added fulvic acid in L-CBF BOOST

By David Maxwell, sales director, QLF Agronomy

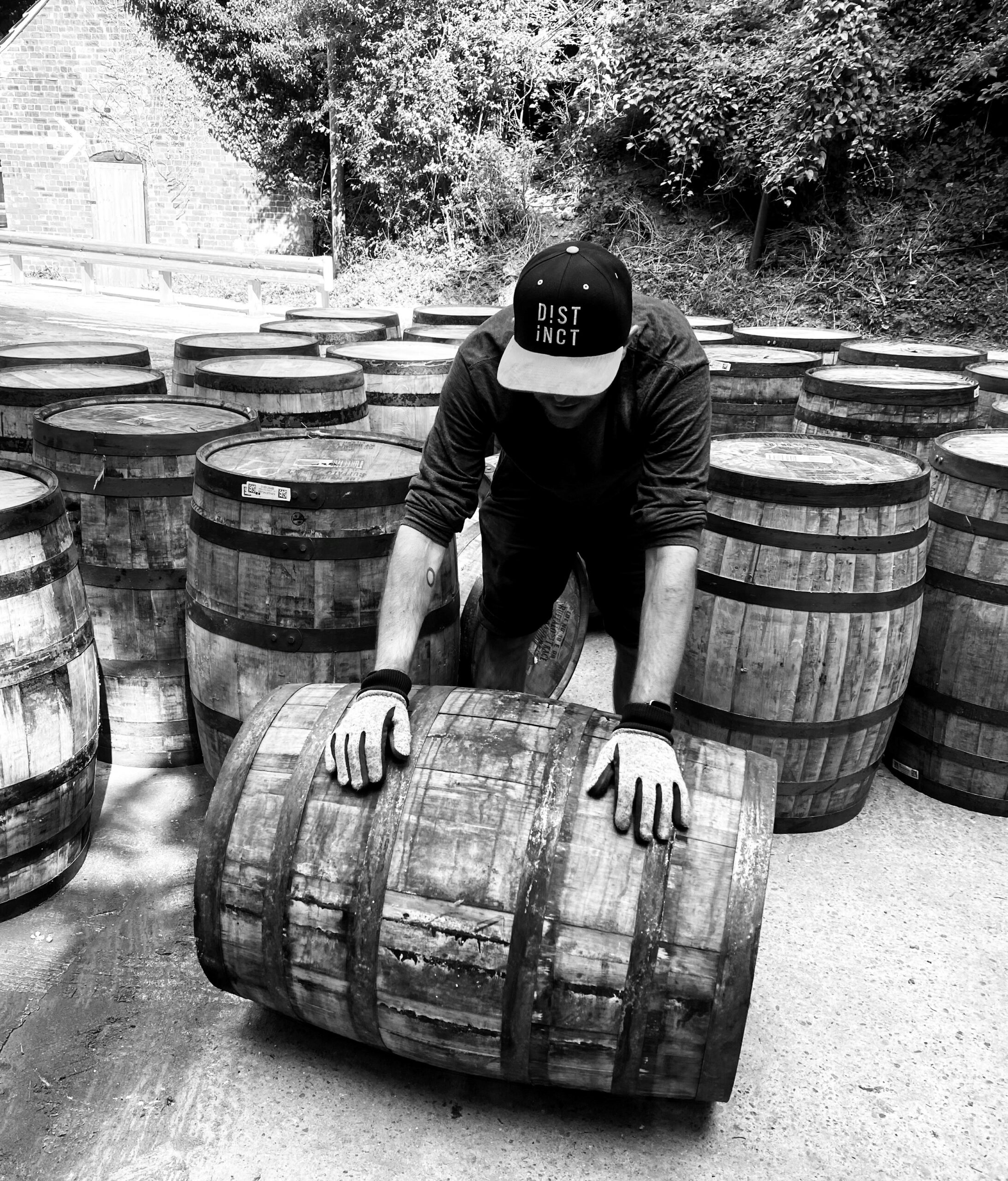

The welcome addition of a family-owned distillery at the site where QLF Agronomy products are manufactured not only gave us a healthy supply of rum, but we have also been able to ‘boost’ our BOOST with added fulvic acid as a byproduct from the distilling process.

Distinct Distillers is co-located with the Landowner, Quality Liquid Feeds and QLF Agronomy manufacturing site. It currently produces several white and dark rums using the same raw material that goes into our QLF Agronomy products – molasses.

The fermentation of molasses creates a lot of nutrients alongside the alcohol, and the distillation kills off any live yeast. What’s left at the end of the process is a distillate that goes to the other side of our manufacturing site for us to utilise in our QLF Agronomy products. This distillate has a high concentration of fulvic acid, which is ideal for adding to our L-CBF BOOST, TL17, TL30 and Amino 15 products.

It’s a win-win. The distillery has a willing customer for what would otherwise be waste, and farmers using QLF Agronomy products benefit from additional fulvic acid for their crops. This is on top of the existing fulvic acid in our molasses-based fertilisers.

With a 1,000L IBC of straight fulvic acid costing around £3,000, what we include from the distillery byproduct adds considerable value to a farmer.

Fulvic acid is a natural organic substance that improves soil health in many ways. Its importance to plant health comes from its open carbon structure and low molecular weight. It is an excellent chelating agent, meaning it can bind to nutrients and make them more available to the plant.

Fulvic acid enhances nutrient uptake by increasing the permeability of plant cell membranes. This results in improved nutrient absorption and utilisation by plants.

Alongside nutrient uptake, the other benefit of including fulvic acid with nitrogen is how it aids the conversion of urea into amino acids by providing a carbon source.

If a farmer applies foliar urea, it will also help uptake into the plant by neutralising the charge on the leaf surface. This stops urea, a positively charged cation, from binding to the surface and not being absorbed.

The molasses that form the basis of our products has similar benefits to plant health, but fulvic acid works in a complementary way.

Fulvic acid’s sister compound is humic acid, which is also becoming an increasingly popular input. It tends to go on the soil rather than the leaf. However, there’s evidence on grassland that humic acid is a more effective foliar feed than fulvic acid.

We don’t get any humic acid from the distillate. L-CBF BOOST already contains humates, the solid form of humic acid. This makes it an exceptionally rounded foliar feed.

Distinct Distillers is about to increase production, giving us access to even more fulvic acid. We are considering if we can use this to introduce a range of specific foliar fertilisers with higher concentrations of fulvic acid. For the moment, farmers can benefit from the flexibility that a product like L-CBF BOOST gives them when they apply it to the soil or leaf.

QLF Agronomy issues a guide to carbon fertilisers

A new technical guide aimed at helping growers understand the benefits of incorporating carbon-based fertiliser in their nutrition programmes has been created by QLF agronomy.

With so much focus in the last 50 years on nitrogen and the nitrogen cycle, the importance of carbon and the carbon cycle has been neglected. The guide explains how maintaining a healthy carbon-to-nitrogen balance helps soil microbes thrive, improves nutrient use efficiency and increases yields.

Contained within is trial data, recommendations for L-CBF BOOST, grower case studies and frequently asked questions. Farmers and advisors who download and read it are entitled to 2 BASIS and 2 NRoSO points.

Distinct Distillers: the drinks company improving soil health

Following a successful career in the drinks industry, Distinct Distillers founder Hannah Boon decided to set out on her own. She set up Distinct Distillers as a separate business from her family’s Landowner Group but linked through the same infrastructure.

They produce dark and light rums and plan to begin producing whiskey soon. The spirits are cask-conditioned underground using an old World War Two aviation fuel bunker. This provides a consistent temperature and humidity, which are ideal conditions for conditioning spirits.

The firm also has a licence to sell its excess ethanol for industrial purposes. They have another on-site customer with the Landowner business, which can use it for its screenwash.

10% off the Distinct Distiller online shop

Direct Driller readers can get a 10% discount on a bottle of Distinct Distiller rum by using the code DIRECTDRILLER10 at the checkout on the Distinct Distiller website.

https://www.distinctdistillers.co.uk/collections

-

Farmer Focus – Andy Cato

September 2024

The deluge of the last few days, following the wettest winter since 1836 and the drought of the previous year, make it abundantly clear that we’re now farming in a fundamentally different water cycle. Improving the capacity of our soils to infiltrate and percolate heavy rainfall is going to be critical for a resilient food supply. In his book, The Last Drop, Tim Smedley describes how the Tribunal de de la Vega de Valencia has met every week in the same spot for the past 1,100 years and is recognized as the oldest court on earth. The irrigation system it oversees is one of the many remarkable stories he tells of water optimisation. Iran’s ancient underground ‘qanat’ water network, for example, would stretch 9x around the equator. He describes how in recent decades these localised systems have been replaced by centralised mega projects: vast concrete dams and canals. These slowly emptying water-infrastructure dinosaurs come with some staggering statistics. Lake Mead, the reservoir formed by the Hoover Dam, loses more water through evaporation every year than the total water usage of Las Vegas.

As with water, so in agriculture, when local and nuanced gave way to centralised inputs, varieties and techniques, the initial miracle came with long term consequences that today are urgent and inescapable. One of the challenges we face at Wildfarmed is that the construction of the Hoover Dam or a huge food processing plant, fits much more easily into today’s investment criteria than introducing permeable urban surfaces to help with aquifer recharge or building infrastructure for local food networks. At the heart of this are the “externalities” that aren’t on the spreadsheet; the massive waste of the Hoover Dam whilst the Colorado river no longer reaches the sea, or the myriad statistics describing nature, water and soil decline, with which we’re all too familiar.

In such a world, where a dead tree is worth more than a living tree, a huge amount of Wildfarmed work goes into trying to create a world where farmers are paid not just for the weight of produce, but for its quality and the quality of the ecosystems in which it was grown. It’s a tribute to the tenacity of the team here that from data capture to financial support, we’re making tangible progress; finalising water company payments for our growers, for example, or Trinity Ag Tech analysis that found biodiversity in WF fields to be 100% higher than adjacent conventional production. Last week, hundreds of test tubes of insects went to Bristol University to be analysed for their quantity and diversity of life, data which is all part of building a picture that can bring value onto farmer’s spreadsheets that goes beyond tonnage of grain.

German government money kick-started a process that reduced the price of solar energy 90% in 10 years. Similarly, we need public money to open markets which reward farming that simultaneously delivers on nature and food security. I’ll leave it to those properly qualified to debate where farmed land should give way to rewilding on the one hand, or the pros and cons of “sustainable intensification” on the other. Between these two ends of the spectrum, there are huge tracts of UK farmland where farming that is properly rewarded to combine both food production and nature recovery, is the only way I can see to achieve 2030 legally binding species recovery targets* without either compromising food security or relying on food produced to catastrophic environmental standards from elsewhere around the world. But doing so depends on fair farmer outcomes, and that depends on value being attributed not just to how much food was produced, but how it was produced.

An invitation to speak at an FFCC gathering at the Labour Conference on Monday came long after a DJ set in Ibiza had been agreed for the night before. It made for a surreal 24 hours. The scenes at 5am and 5pm were quite different.

But there was a link. A sign held up in the front row of the Ibizan crowd said “Clarksons! Nature farming ❤️”. Another simply said “Wildfarmed”. A landmark of the last few months has been surpassing 100k Wildfarmed Social Media followers, engaging with the stories of our farmers, bakers, chefs and retailers. In the conference room at the Leonardo Hotel, alongside James Rebanks and Sophie Gregory, I had ten minutes to make my case. The nub of it was that there are lots of good things in today’s SFI, and DEFRA are certainly listening; the changes to AB14 about which I’d been nagging anyone who’d listen for several year did eventually come through, allowing cereal blends, companions and drilling after rape and beans (this is option is now known as AHW10).

But since 1987, when the UK pioneered one of the world’s first Agri-environment schemes, we have sought to increase biodiversity by taking farmland out of production. This shadow of nature and food being a mutually exclusive choice hangs over the SFI, and AHW10 was always an imperfect and temporary solution. A transformational SFI option would be one that gives proper value to nature rich food production, recognising its potential to match or exceed the biodiversity present in today’s well paid, non-productive environmental options. Some of the insect samples sent off to Bristol for analysis showed greater insect abundance in food producing Wildfarmed fields than in £763/Ha beetle banks. Equally transformational would be making certified nature-rich arable a BNG eligible landscape. Food, Nature and Biodiversity Net Gain (FNBNG) would be a global first, bringing BNG outcomes into food-producing landscapes and unlocking private money for farmers who are delivering on both nature recovery and food security in the same place at the same time.

Key to both is measuring outcomes. When the Wildfarmed Standards were drawn up, only 3 years ago, the world of outcomes monitoring was a very different, sparsely populated place. Since then, progress has been rapid and points to a near future where we might replace defining farming practices and define required outcomes instead. An example are polyphenols (anti-oxidants) as indicators of nutritional integrity and therefore functioning soil biology. Back in 1948 William Albrecht correlated the health of US sailors to the health of the soils in their native regions. 80 years later, talk of nutrient density is increasingly common. But a perfectly grown carrot in fully functional soil will have different nutrient levels depending on the geological history of the area. Antioxidants might therefore be a useful indicator of nutritional quality whatever the soil type. We’ve been measuring batches of WF grain for polyphenols over the past few years and found increases of 40% to 100% relative to nearby conventional fields. It will be interesting to see how this data builds up and it’s a shame that such important work is so expensive. Given the epidemic of diet related disease bringing the NHS to its knees, some public money here would be well spent.

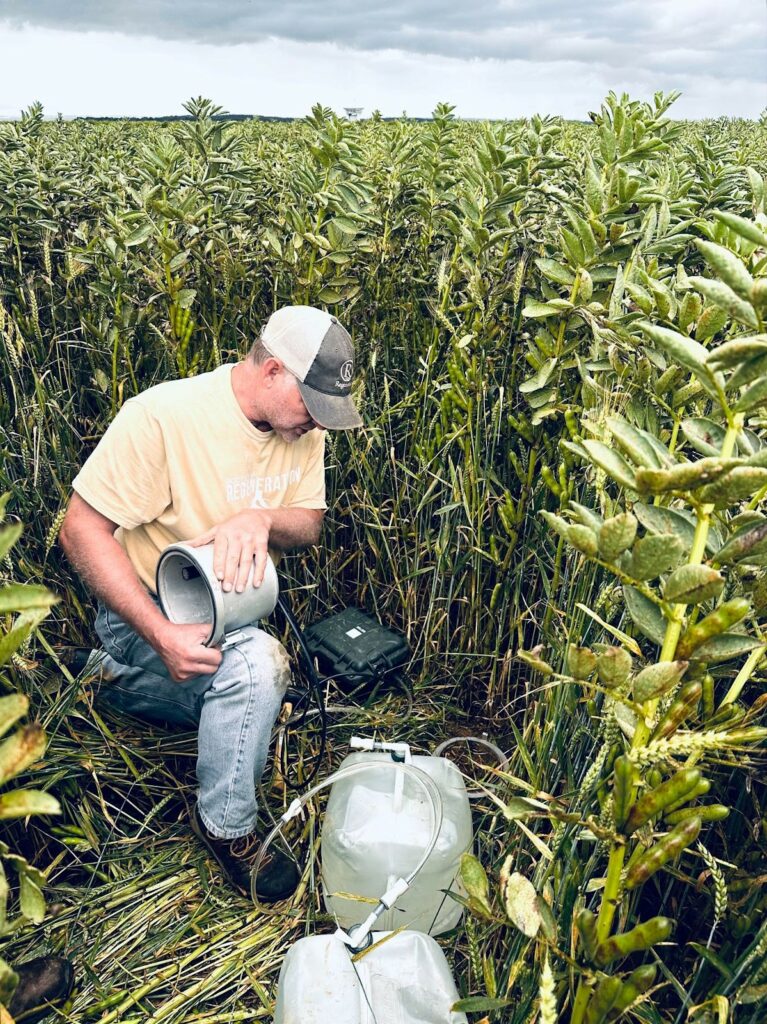

From Acoustic measurements of soils as an indicator of overall system health to satellite analysis of Nitrogen leaching, so many partnerships with Wildfarmed growers are underway to push outcome measuring forward. This includes a pilot with Regenified to gather data across 10 of our farms. On one of them, the Leckford Estate, the Waitrose & Partners HQ with a long history of pioneering farming, I waded into a field of towering wheat and beans to watch Doug Peterson, technical head of the Regenified program, deploy an infiltration measuring machine that costs the same as a family car. This is in stark contrast to the 6” pipe, hammer and ½ litre bottle of water which are my usual tools of the trade.

Infiltration is not only a critical measure of farm resilience in a time of downpours followed by drought but is also itself emerging as a powerful overall indicator of soil health. In a recent highly recommended John Kempf episode with Keith Berns from Green Cover seeds, they discuss the increases in infiltration rates that flow from diverse cover crops, and the increases in water use efficiency of diverse plant communities. Infiltration means porosity, and porosity means carbon and life. In our work with Andy Neal at Rothamsted, porosity, measured using topographical profiling of the soil, is his favoured measure of health.

But amidst all this innovative technology, let’s not forget the creature that is to the soil what the Harpy Eagle is to the forest – the worm. This summer, Jeremy Clarkson put his Wildfarmed fields into a summer long cover crop. Kaleb’s tine drill put the mix in a bit deep, and he’s since fixed himself up with a broadcaster over the drill tines so that next time he can create some tilth whilst tickling the seed into the surface. But despite losing some of the smaller seeded species to these depth issues, the worm count a month ago was amazing. The two samples below show a shovel of soil from the field over the hedge where peas had been harvested, and a shovel from the cover crop field a week after it had been flailed. (Worms under and in the soil samples were put on top to be counted). The next challenge will be getting these fields back into Oats and Beans. There are many areas where the soil goes from Cotswold brash to Cotswold crazy paving.

The big event at the battle of Shrewsbury, as the story unfolded on a recent Rest Is History podcast, was the future Henry V getting an arrow in the eye. The big event for me was hearing how his army advanced through a fields of peas that were full of snakes. I was left wondering where all the snakes have gone and reevaluating the widespread introduction of legumes into English farming which I’d always thought came in the 18th century with Townshend’s Four Course Rotation: Wheat-Turnips-Barley-Clover. I hadn’t realised that legumes had been so widely grown since the Middle Ages, and not just peas but beans and vetches too. It seems to have been the increased Nitrogen fixation of clovers together with replacing fallowing for weed control with hoe-able turnips, that really changed Townshend’s levels of productivity.

But as farmers up and down the country discovered last winter, having soil available nitrogen at the beginning of a cropping cycle is one thing. It being used by the following crop is another and is not straightforward or linear even before we throw in record amounts of rain. It became clear this spring that the amounts of available Nitrogen predicted by soil tests were not becoming a reality, either because of over-winter leaching, or because months of waterlogged conditions meant that the required soil biology wasn’t there. As a result, protein levels were down across the board. For some Wildfarmed growers, already using split N doses and SAP to make a little Nitrogen go a long way, our nutrition-based-on-need approach came up short; the need couldn’t be met. This was one of the key takeaways from the annual process of gathering data and experiences of all our farmers. Combined with the latest learnings from partners such as AEA and Regenified, we’re constantly looking for the best way to facilitate a scalable transition towards farming that meets Wildfarmed customers guarantees: farmer community support, fair farmer outcomes, nature-rich fields, pesticide free grain, avoidance of water pollution, better carbon efficiency.

Avoiding attachment to long held ideas in the face of new evidence is far easier said than done. One of many examples was when, in grass-based Surrey pastures, my first attempt at inter-row-mower pasture cropped UK wheat went into reverse in the spring. Simultaneously I had come across the work of Dr Christine Jones and realised that pasture cropping successes in France hadn’t been because the inter-rows were perennial, but because they were forb based and diverse. Staring at the yellowing, non-symbiotic relationship between annual grasses – wheat – and perennial grasses in those Surrey fields was humbling given I’d thought about pretty much nothing else other than blade tip speed and the million other practical problems that had needed solving throughout the evolution of various mower prototypes over the preceding years. And yet based on the new information, given plant family diversity was the key, and that we were trying to make implementation as easy as possible, surely step one should be the use of poly or bi-crops and cover crops, all doable with existing equipment, rather than try and build a world’s worth of mowers?

Helpful in these moments is to be reminded of the dizzying speed of ecosystem change relative to the trees still alive today that were seedlings when Mammoths walked the earth. Last week, an article detailing further catastrophic butterfly decline and another citing increased pesticide residues in food, were both followed by 5 inches of rain in 24 hours. We’re assailed on all sides by evidence for the urgency of a transition. As such, evidence-based decisions, and avoiding dogma, are, I think, critical if we’re to build field to plate collaborations at the size and scale required to turn things around.

For this year’s annual review around nitrogen, the course correction was more straightforward. The data showed that the amount of N expected from soils that didn’t materialise averaged 40kg. Simply hoping this doesn’t happen again is clearly not an option; without good farmer outcomes, there is nothing to talk about. Instead, we changed the soil-applied nitrogen allowance for our winter sown cereals, from 80kg to 120kg, delivered as always in the split doses of no more than 40kg that are crucial for water quality. Interestingly, studies in Agronomy , Field Crops Research r and Science Direct, all coalesced around 120kg in split doses as the sweet spot between N use efficiency and yield. Given Wildfarmed growers don’t have recourse to pesticides, caution around N use is inevitable given that excess is a sure-fire precursor to disease, or increased weed burdens.

Radical differences in rainfall from one season to the next also affect the management of companion crops; there appeared to be a correlation this year between wetter areas of fields and beans getting ahead of the wheat. It also, of course, has an impact on weeds. This year we’ll be running a series of trials to see how we can best manage both issues in the context of our customer guarantees. Inescapable in these low input systems are all the basics of good husbandry; a rotation that has setup the crop for success followed by good establishment at the higher end of recommended plant populations.

In his book La Vie, John Lewis-Stempel describes a year of small-scale agriculture in a village in the Charente. He measures the output of his vegetable garden and finds the calories produced per sq m to be three times higher than the large-scale farming he had practised in the UK. We encounter this question of scale all the time. On large arable holdings, having enough time to farm differently on a portion of that land can be challenging. And yet pinning a different future on land redistribution feels like rearranging titanic deck chairs. Meeting the world as it is means constantly trying to refine the management of nature rich arable so that there is enough time to focus on the most important thing of all. As Wildfarmed grower Duncan Fairburn put it last week “farming with your eyes”.

This summer saw the arrival of Wildfarmed loaves on the shelves of Waitrose. The first time I saw them in situ, I stood in silence for a while, marvelling at all that had happened to make those loaves become a reality. Building a farming community field by field, the research, agronomy and support team that surrounds that, paying farmers fairer prices whilst trying to remain affordable, bringing everyone across the supply chain together in fields across the country to explain what we’re doing and why, the post-harvest grain separation, storage solutions and milling partners that allow us to keep our grain segregated and traceable from field to plate, persuading plant bakeries operating on wafer thin margins to abandon the Chorleywood process, do an overnight fermentation, leave out the additives, or persuading packaging companies to accept what for them are totally inconsequential print runs. On and on it goes, and then to bring all this together and get a commitment from the different strata of the Waitrose supermarket team to make the first change on the bread isle for 125 years. It’s so incredibly complicated and I take my hat off to the Wildfarmed team for having pulled it off, despite doing so in a market that places no value, yet, on the wider societal benefits of any of this.

Last night, our growers had a post-harvest celebration in the beautiful, wooden dining room at Farm Ed. Farmers are the most resourceful people in the world, and, properly supported, can deliver whatever food and landscapes society asks of them. The last few years have made it clear to me that we can have a future in which farmers are getting fair returns not just for the quality of their food, but for the quality of the ecosystems in which it’s grown. We could have fields that are still full of healthy crops despite the wild changes in rainfall patterns because the soil can infiltrate and percolate water. We could have the brightest young minds coming into food and farming because it’s cool and aspirational. We could have NHS waiting lists coming down because we’re talking about food as medicine. We could have reports in the paper about species diversity going up and up every year. We can do all these things. It’s simply a question of whether, as a society, we choose to do so. As Jane Goodall put it, her diminutive figure on a grey, early morning Glastonbury stage this summer still inspiring new generations to action, “What you do makes a difference – decide what difference you want to make.”

*2019 Environment Act

-

Timing is everything

Reflecting on last season’s challenges and the lessons learned Jeff Claydon, Suffolk arable farmer and inventor of the Claydon Opti-Till® direct seeding system, outlines some of the changes he will be making for the 2025 harvest.

August 2024

The title of my last article ‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ (Issue 28 – July 2024) summarised the appearance of crops on our own and many other farms at that time. Unfortunately, that continued to be the case right through to harvest. As expected, those established on well-drained soils worked under the right conditions performed well, while those muddled into heavy land in poor conditions were downright ugly. But, as one of our contract customers said, ‘at least we were lucky to have a harvest.’

If last season taught us anything it is that farming successfully depends on working with, not fighting, the weather. Last autumn we pushed our luck a little too far based on idealistic thoughts of drilling later than normal. At the time, many were talking about how this approach would help to control grassweeds and as we prepare fields for drilling using only the Claydon Straw Harrow, an extremely fast, low-cost operation, we decided to give it a go. What could possibly go wrong? What indeed!

Failing to heed the advice which my grandfather gave me when I started in this industry, we overlooked the fact that you cannot farm based entirely on what date is showing on the calendar. We left it until 15 October before starting to drill winter wheat and on 11/12th October we had a deluge of 60mm of rain. Within three days of drilling, a further 90mm of rain fell. During the remainder of the month we had an average of 1cm per day after drilling!

Suddenly all the lights went from ‘green’ to ‘red’ and ultimately we paid a heavy price for going that route. Last season’s crops were amongst the most variable that I have ever seen on this farm in more than 50 years. There were multiple reasons why, including the fact that some crops were established in poor conditions, in places drainage was sub-standard, while slug and grassweed pressures, normally well contained, were exacerbated by the wet weather.

Looking through reports from Claydon customers last week I noted that some who drilled wheat on free-draining soils in the first week of October harvested over 11t/ha. Others, who mauled seed into cold, wet heavy clay soils at the end of the month achieved less than half that. Given the wet conditions our oilseed rape and wheat were never likely to make the ‘good’ category, but spring oats did make par relative to the long-term average.

Just before harvest we replaced our 12m Claas Lexion 600 with a 10.8m Claas Lexion 760 Terra Trac. Despite its narrower header the output is an almost identical 4ha/hr due to the combine’s latest technologies which increase throughput and forward speed.

The new Claydon Mole Drainer was used extensively this year until the soils became too dry. We also part-exchanged the 2011 340hp John Deere 8345R which had been our main tractor for several years as it no longer had a real place in the fleet following the arrival of a 415hp Fendt 942 last season. Too big for jobs such as pulling our 15m Claydon Straw Harrowing and trailer work, the 8345R has been replaced by a 240hp Fendt 724 which is much more versatile and fuel efficient.

ADDED COMPLEXITY

Adding complexity to an already difficult season, ergot (Claviceps purpurea) resulted from the very wet weather. We recorded a smattering of it, 8-15 per sample, not a high level given the season and what was seen elsewhere, but the UK sets something of a gold standard, specifying zero ergot per sample for grain going into the human food chain and an EU-standard 0.001% tolerance for feed grains. Unfortunately, growers carry the additional risk of significant price deductions or the cost of rejected loads caused by a problem not of their making. Is that fair?

Reflecting on an exceedingly difficult season many of us would admit that, with the benefit of hindsight, we would have done some things differently. So where do we go from here? That may depend on whether you see the glass as being half full or half empty. On the Claydon farm we did not achieve the yields we wanted but moaning won’t do any good, so instead I am writing off last season as being ‘just one of those years.’ It was much the same in 2012, but in 2015, having done nothing different, we recorded 13t/ha.

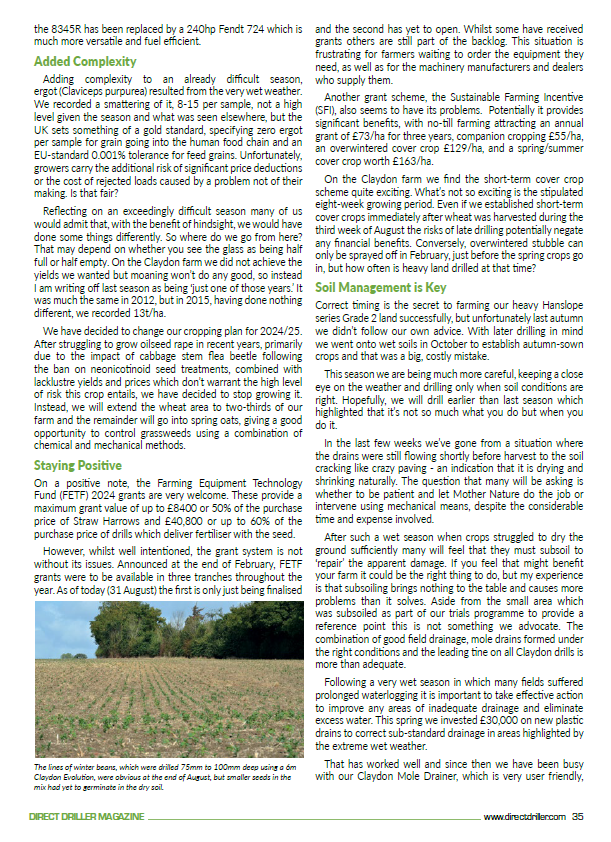

We have decided to change our cropping plan for 2024/25. After struggling to grow oilseed rape in recent years, primarily due to the impact of cabbage stem flea beetle following the ban on neonicotinoid seed treatments, combined with lacklustre yields and prices which don’t warrant the high level of risk this crop entails, we have decided to stop growing it. Instead, we will extend the wheat area to two-thirds of our farm and the remainder will go into spring oats, giving a good opportunity to control grassweeds using a combination of chemical and mechanical methods.

The 6m Evolution drill and new Evolution Front Hopper being used to establish a cover crop, powered by the 415hp Fendt 942 Vario. STAYING POSITIVE

On a positive note, the Farming Equipment Technology Fund (FETF) 2024 grants are very welcome. These provide a maximum grant value of up to £8400 or 50% of the purchase price of Straw Harrows and £40,800 or up to 60% of the purchase price of drills which deliver fertiliser with the seed.

However, whilst well intentioned, the grant system is not without its issues. Announced at the end of February, FETF grants were to be available in three tranches throughout the year. As of today (31 August) the first is only just being finalised and the second has yet to open. Whilst some have received grants others are still part of the backlog. This situation is frustrating for farmers waiting to order the equipment they need, as well as for the machinery manufacturers and dealers who supply them.

Another grant scheme, the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI), also seems to have its problems. Potentially it provides significant benefits, with no-till farming attracting an annual grant of £73/ha for three years, companion cropping £55/ha, an overwintered cover crop £129/ha, and a spring/summer cover crop worth £163/ha.

On the Claydon farm we find the short-term cover crop scheme quite exciting. What’s not so exciting is the stipulated eight-week growing period. Even if we established short-term cover crops immediately after wheat was harvested during the third week of August the risks of late drilling potentially negate any financial benefits. Conversely, overwintered stubble can only be sprayed off in February, just before the spring crops go in, but how often is heavy land drilled at that time?

A sample of the Elsoms Lion spring oats. SOIL MANAGEMENT IS KEY

Correct timing is the secret to farming our heavy Hanslope series Grade 2 land successfully, but unfortunately last autumn we didn’t follow our own advice. With later drilling in mind we went onto wet soils in October to establish autumn-sown crops and that was a big, costly mistake.

This season we are being much more careful, keeping a close eye on the weather and drilling only when soil conditions are right. Hopefully, we will drill earlier than last season which highlighted that it’s not so much what you do but when you do it.

In the last few weeks we’ve gone from a situation where the drains were still flowing shortly before harvest to the soil cracking like crazy paving – an indication that it is drying and shrinking naturally. The question that many will be asking is whether to be patient and let Mother Nature do the job or intervene using mechanical means, despite the considerable time and expense involved.

After such a wet season when crops struggled to dry the ground sufficiently many will feel that they must subsoil to ‘repair’ the apparent damage. If you feel that might benefit your farm it could be the right thing to do, but my experience is that subsoiling brings nothing to the table and causes more problems than it solves. Aside from the small area which was subsoiled as part of our trials programme to provide a reference point this is not something we advocate. The combination of good field drainage, mole drains formed under the right conditions and the leading tine on all Claydon drills is more than adequate.

Following a very wet season in which many fields suffered prolonged waterlogging it is important to take effective action to improve any areas of inadequate drainage and eliminate excess water. This spring we invested £30,000 on new plastic drains to correct sub-standard drainage in areas highlighted by the extreme wet weather.

That has worked well and since then we have been busy with our Claydon Mole Drainer, which is very user friendly, simple to set up, easy to use and allows small adjustments to be made as the bullet wears to keep it operating at optimum efficiency. One-third of the farm was mole drained last autumn and another third this year, some in the spring and some immediately after harvesting oilseed rape, all in excellent soil conditions. Mole drains can last up to 20 years so doing the job well will pay handsome dividends.

At 5% to 7%, organic soil matter levels on the Claydon farm are well above average and digging down revealed root channels from last season’s crops, so clearly it is restructuring naturally. Over the August Bank Holiday 13mm of rain fell and 48 hours later the top 5cm of soil was in beautiful condition yet below that it was as hard as a rock. The hard, dry conditions meant that we had to stop mole draining during the second week of August. We plan to finish the other third of the farm in the spring through the standing crops.

In recent years we’ve become particularly good at minimising blackgrass in the autumn, but now it’s spring-germinating blackgrass that’s the issue. We are controlling it very effectively using a combination of chemicals and our 6m Claydon TerraBlade inter-row hoe, so hopefully persistence will pay off.

THE SFI OPTION

Having expressed interest in the SFI for the Claydon Farm but with no response from Defra, after harvesting oilseed rape at the end of July we drilled a short-term cover crop which looks good. We modified our 6m Claydon Evolution drill so that the fertiliser injector sits behind the front tines allowing the beans to be placed 75mm – 100mm deep directly into moist soil and they germinated very well.

Buckwheat makes up 63 per cent of the cover crop mix. The other small seeds which make up the short-term cover crop we drilled behind wheat (Hutchinsons’ Maxi Catch Crop – Buckwheat (Polygonaceae Fagopyrum), Zoltan spring linseed, Ascot white mustard and Tabor Egyptian clover) are currently sitting in dry soil and have yet to emerge. It will be interesting to see if the cover crops encourage a flush of blackgrass when removed later in the autumn, something we can do as they are not under SFI. The plan is to follow with winter wheat and spring oats.

Even King Canute would have been challenged to deal with the tide of water which hit us last autumn. Farming is not an industry where you can be prescriptive when it comes to timings, so it is essential to adapt to the conditions which Mother Nature presents. This appears to be lost on some of the policymakers who make the rules which farmers must follow, and they seem to have little understanding of what happens in the real world!

Last season tested everyone farming at a practical level, so we must be open-minded and work out how to get the best results from our investment going forward rather than doing things the way we have always done. On the Claydon Farm we aim to start drilling during the last week of September or first week of October because even placing seed into dry soil when rain is forecast is better than waiting for rain and sowing into wet soil. As it is relatively easy to grow another good crop following a good crop our main goal this season will be to ensure that everything falls into that category rather than the bad or ugly.

-

Early sown winter wheat returns to heavy land blackgrass site

High yielding, profitable early-sown winter wheat crops are once again a regular feature on the heavy land rotations at Lamport AgX, Agrovista’s flagship trials site in Northamptonshire, despite a huge background population of blackgrass.

Speaking at a recent open day, Niall Atkinson, consultant and Lamport AgX trials co-ordinator, said: “Historically, if wheats weren’t drilled by mid October you risked not getting them in at all. But going earlier was asking for trouble – blackgrass populations exceeded 2000 plants/sq m on this site before it was established in 2013.

“Lamport AgX is all about solving this conundrum. We’ve learnt how to do that, using sequences of autumn cover crops and spring break crops such as oats, beans or barley to reduce blackgrass pressure, minimising soil movement when establishing cash crops, and improving soil health to help create a favourable environment for wheat.”

The Lamport concept, backed up by an appropriate herbicide programme, has proved itself over several very different seasons. In 2023 first winter wheats averaged just under 10.5t/ha following a range of different crops, with some plots exceeding 12t/ha, with almost no blackgrass.

“After a run of autumn cover crop/spring breaks, we are now successfully alternating winter wheat with a cover/spring break,” Niall said.

“But you need to choose your fields carefully and stick to the guidelines or risk going backwards. You also need to be reactive – if something goes wrong and blackgrass starts taking hold, you may need to delay your first wheat and grow a further cover crop/spring crop break.”

Integrating SFI into farming systems

Much of the work carried out at Lamport can attract valuable SFI payments. Over-winter cover crops, the mainstay of operations to control blackgrass and improve soil health are currently worth £129/ha, but that’s just the start. Several other options that now attract payments under the scheme are under scrutiny.

Whole field SFI actions are proving difficult to integrate into rotations at Lamport due to the enormous blackgrass challenge.

Winter bird food (AHL2) and legume fallow (CNUM3), look tempting on paper, paying £853 and £593/ha/year respectively. But both plots, which were drilled in April, have been destroyed.

Hamish Wardrop, Agrovista’s rural consultancy national manager, said: “The winter bird food established OK but there was a mass of grass weeds as well, and the pressure was too high to continue with it on this site.

“The legume fallow also established reasonably well, but it suffered badly with slugs, flea beetle and weevil. And we also have grassweed pressure.

“These actions can be a good choice in some situations, but you have to go in with your eyes open. We can’t lose sight of what we are trying to achieve in bringing back first wheats into the rotation.”

Low input cereals

A low-input cereal action (AHW10) aims to create an open-structured cereal crop that encourages wildflower species to grow within it, providing habitat and summer foraging for birds, pollinators and other wildlife.

It pays £354/ha/year under SFI, whilst a further £129/ha is available for a preceding over-winter cover crop.

Technical manager Mark Hemmant said: “Herbicides are restricted and you have to sow the cash crop at a reduced seed rate – we chose spring oats and went at two-thirds rate, or 270 seeds/sq m.

“We have to select carefully where to grow this action at Lamport, but we have achieved the aims; while is a little bit of blackgrass coming through, if you are well on top of grassweeds and have a good rotation, it could be useful.”

Spring wheat and beans

The benefits of adding beans to a spring wheat crop at 10 seeds/sq m are also being assessed. That would attract a £55/ha companion crop payment under SFI for a seed cost of about £15/ha, and could help mitigate take-all.

“The net benefit of what you spend on bean seed compared what you get back looks good, provided there are no adverse effects on blackgrass control or yield,” said Mark.

The beans were destroyed around flag leaf timing as some inputs are not approved for that crop, but the crops appear to have thrived.

“We know at Lamport that black oats in the cover crop aren’t enough to prevent take-all in a wheat-dominated rotation in an autumn like 2023,” he explained. “But if we introduce wheat plus beans in the spring, might the undoubted soil benefits that beans bring change things?”

Does direct drilling affect herbicide choice?

On any farm with a grassweed problem, selecting the best herbicide programme is vital to reinforce the effect of cultural control measures to achieve optimum control.

However, there is little information available on whether different cultivation strategies, particularly direct drilling, affect herbicide efficacy.

In previous years Mark has generally found cinmethylin (as in Luxinum Plus) and aclonifen (as in Proclus) to have similar activity on blackgrass. However, cinmethylin is claimed to have an impact on seed on the surface, so a trial to assess whether it might be a better pre-emergence option was set up at Lamport in 2022/23 and continued this season.

The trial compared blackgrass levels and wheat yields across several cultivation strategies, ranging from direct drilling to deep loosening. These were treated with five pre-emergence regimes – untreated, aclonifen/DFF/flufenacet, and cinmethylin/pendimethalin/picolinafen, both +/- triallate (as in Avadex).

“In two very different years we did not see any significant benefit of cinmethylin over aclonifen-based herbicide options pre-em, even where direct drilling,” Mark said.

“Although not statistically significant, the aclonifen-based herbicide appeared to work better in the dry conditions of autumn 2023 and exhibited better crop safety in the wet autumn of 2024, the latter particularly with establishment systems where less soil was moved and or where shallower drilling took place.

“In addition, consistent benefits of moving less soil in grassweed levels and of including Avadex were seen in both seasons.”

In other trials, best control of blackgrass has consistently come from using both actives in sequence – aclonifen pre-emergence followed by cinmethylin early post-emergence.

“The results from the Lamport trials confirm that this approach, and that the addition of Avadex pre-emergence is appropriate whatever the cultivation method,” said Mark. “And it reiterated the fact that moving less soil reduces grassweed pressure.

“The take-home message is that no herbicide programme is good enough on its own,” he added. “Heavy infestations of blackgrass also require appropriate cultural controls to achieve the desired result.”

Low-pressure tyres on test

The effectiveness of new low-pressure tyre technology in reducing soil compaction was put to the test at Lamport this season.

The trial used a John Deere 6155R tractor with a mounted 3m Weaving direct drill running on Michelin AxioBib 2 VF tyres or and Galileo AgriCup tyres.

The AgriCup is a low-inflation design that, according to the manufacturer, combines the benefits of pneumatic tyres and rubber tracks, producing a 17% larger footprint than a standard tractor tyre.

Tyres were tested on winter wheat and peas drilled after an over-winter cover crop established on soil previously loosened to 15cm.

Independent cultivations consultant Philip Wright said: “The VF tyres were run at 18psi, which is clearly quite extreme, and 11psi, as low as we dare go with the loaded mounted drill. The AgriCups were inflated to 6psi.”

The untrafficked area between the wheelings unsurprisingly looked the best. Of the trafficked areas, the VF at 11psi left the best soil structure and the best crop rooting and canopy for both peas and wheat.

The AgriCup was marginally behind, causing some surface compaction and intermediate rooting but a good canopy. The 18psi VF tyre created the highest surface compaction and poorest rooting.

Earlier work elsewhere carried out by Philip has shown cereal yield losses rising to 30% on heavy soils in areas trafficked by a tractor fitted with VF tyres inflated to 14psi towing a 3m direct drill.

Whilst not pre-judging the Lamport results, he said: “The AgriCup tyre has quite a robust construction, so in damper conditions we could see a slightly greater imprint.

“The biggest markets currently are for skid-steer loaders and irrigation gantry systems, but they could be useful on a crop establishment system that uses quite heavy rear-mounted kit,” he added.

All plots will be taken to yield.

Avoid unnecessary soil loosening

The importance of avoiding unnecessary subsoiling operations was clearly illustrated in results released at the Lamport AgX open day from trials carried out in 2022/23 on Lamport AgX’s difficult silty clay loam.

Loosening an uncompacted plot with a low-disturbance subsoiler to 15cm before direct-drilling winter wheat created an open structure between the subsoiler legs and resulted in good root growth.

However, soil disturbed by the legs was left more fragile and slumped to depth, stifling root growth and creating an inconsistent wheat canopy across the plot.

Yield on this plot dropped to 86% compared with an adjacent uncompacted and unloosened plot, nearly as bad as a compacted plot.

“Less can be more, so check soils carefully,” said Philip. “If they don’t need loosening – they are better left alone.”

-

Farmer Focus – Andy Howard

Innovation: Fun but potentially painful

I was recently nominated for the BBC’s food and Farming Awards under the “Farming for the Future” category. Awards are not really in my comfort zone and I thought hard about whether I wanted to accept the nomination. What convinced me to accept the nomination was the fact that the BBC are impartial, with no commercial input/bias in the awards. At the time of writing the judges haven’t yet visited. Their imminent visit has made me reflect on what we have trialled over the years, it’s not until I stopped to think, that I’ve realised how much we have done. I guess some would argue that I’m addicted to on-farm trials and they may be right. I’m a firm believer that you need to trial new ideas on your own farm to see if they work for you. Going to trial plots around the country can be interesting but can also be irrelevant to your own situation.

With this in mind I thought I’d use this article to talk about what we’ve trialled this year, the results and what we plan to do next season.

We have had 2 big replicated trials on the farm this year. The first is trialling the impact of Compost Extract on wheat yields and nitrogen need, with Kent Wildlife trust and Reading University as partners. Plots were with and without extract and 4 different nitrogen rates from 0 to 240kg/N/ha. Initially in the autumn I was very excited about this trial. The plots with compost extract applied with the seed had much larger root systems. This difference disappeared as the season progressed and in the spring I could not visually see any difference between with and without extract plots. So it was a surprise that in terms of wheat yields the extract plots gave an average of 0.4t/ha yield increase. This though was not statistically significant as you need a 95% confidence and it came up just short at 93%. We are doing the same trial again next season and it’s being expanded to two farms. With a few tweaks we hope for a more positive result next year.

Our 2nd replicated trial on farm is part of a Project called N2 Vision+, it’s partially funded by Innovate UK and is in conjunction with Manchester Met University, Royal Holloway University and Autodiscovery Ltd. The idea is to be able measure nutrient content of plants by using visual digital instruments and then apply the nutrients needed regularly using foliar fertiliser from a robotic platform. We have already proved that using deep learning we can detect nutrition using digital imagery. This year we trialled trying to replace all wheat nitrogen demand through foliar fertiliser and comparing to solid fertiliser. Unfortunately border control got in the way of this trial. The application equipment needed for the trial came from France, it got stopped at the border for weeks and mired in paperwork ( a Brexit benefit?). This meant we started foliar applications too late and they never caught up. I do believe we can get more out of foliar fertilisers but it involves going through the crop multiple times which isn’t practical for a crop sprayer but hopefully is for a robotic platform. The numbers are still being analysed at the moment.

We also had a number of simpler (less scientific) tramline trials. The first was comparing different companion species for planting with wheat. I had done the trial 4 years ago and so had a good idea of what wouldn’t work. This year we trialled: beans, vetch and peas and a combination of all 3. Beans were the best but we are going to plant a mixture of all 3 to spread our risk. Also I am going to trial broadcasting linseed before drilling to give extra biomass going into the winter. The seed for this trial was kindly donated by Kings Crops.

Bean foliar disease as we know can be devastating in terms of yield if you get treatment wrong. So after hearing of Ben Taylor Davies’ experience of using Scyon, a biostimulant, last season I decided to trial the product here this season. The Scyon plots had 3 applications of biostimulant and the plots next door had no Scyon, but had fungicide applications as needed. During the season (which was wet and ideal for Chocolate Spot) we couldn’t see any difference. The combine also showed no difference. This gives me confidence to expand it’s usage next year and try on other crops.

A trial we repeated this year was with Protozoa tea. Last year we saw a moderate yield benefit in wheat but a huge yield increase in Herbage seed.

This year we saw the same again, the interesting observation from this year was that where we applied the tea last year as well as this year there was an even bigger yield benefit. The benefits seem to compound. The usage of Protozoa tea here seems very beneficial.

Not an official trial but confirms a previous trial done, was with the use of wheat variety blends. We had two fields next to each other. One a crop of Crusoe and the other a 5 way blend of varieties including Crusoe. The crop of Crusoe got Brown rust very early and took us by surprise, the rust was impossible to eradicate and ended up reducing the crops leaf area. In the end the wheat blend yielded 2t/ha more and we spent £100/ha less on fungicide. It’s a simple technique that seems to work for us.