If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

BYDV-resistant wheats prove their worth in a difficult season

Written by Robert Harris for RAGT

Perceived as niche when introduced five years ago, RAGT’s BYDV-resistant wheats are now catching the attention of a significant number of farmers.

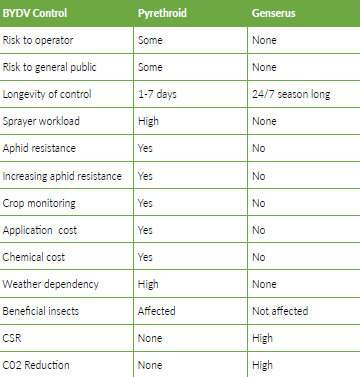

Marketed under the Genserus (Genetic Security Virus) brand, these wheats offer season-long control of BYDV, removing the management headaches of autumn aphid control, eliminating the risk of resistance and protecting the environment.

Direct Driller caught up with two growers who tried different varieties last season to see if they lived up to expectations.

Switch to RGT Grouse pays off in Suffolk

After a five-year battle against barley yellow dwarf virus, Michael Gooderham believes he has found a permanent solution by employing genetics rather than unreliable insecticide sprays to control the disease in wheat.

Much of the arable land Michael and son Darren rent at Red House Farm near Eye borders large blocks of woodland and grass, creating a sheltered habitat for aphid vectors of BYDV.

“After the demise of Redigo Deter we really struggled with the disease, so we’ve been under pressure to get everything sprayed,” says Michael. “We saw RGT Grouse advertised as a resistant variety and, after doing our own research at various open days, decided to try some last autumn. It has paid off big time.”

Conventional varieties on the farm received one insecticide spray last autumn, but a second application was shelved after more than 100mm of rain fell in late October. “By late spring, BYDV was evident in our other varieties, particularly in second wheat which suffered badly,” says Michael.

Gleam made up the bulk of second wheat, along with 14ha of feed wheat RGT Grouse, both drilled in early October. Gleam produced a ‘disappointing’ 8.4t/ha, while Grouse yielded 10.3t/ha.

“I was more than pleasantly surprised,” says Michael. “The difference was not entirely down to BYDV, as the Gleam had poorer headlands, but I could see BYDV clearly when spraying at T2 – the flag leaves were discoloured and going purple in places.”

RGT Grouse was also grown as a first wheat after beans, drilled in late September. The 51ha crop averaged 10.8t/ha, edging Dawsum after sugar beet which missed the main aphid migration.

“The variety has done very well as a first and second wheat and we’ve put it into the IPM 4 insecticide-free crop option under SFI, which earns an additional £45/ha,” says Michael. “It certainly looks to be a good fit for our farm.”

RGT Goldfinch delivers the goods in Northants

“A real step forward. Awesome is the only way to describe it.” Northamptonshire grower Andrew Pitts’ first experience with new quality wheat RGT Goldfinch has, to say the least, gone very well.

“Goldfinch is resistant to BYDV and orange wheat blossom midge and it has the best disease resistance profile out there,” he says. “It’s produced high yields and great milling quality, ticking all the boxes in a very difficult year.”

The 40ha seed crop was direct-drilled at the end of September after peas on medium-bodied land at The Grange, Mears Ashby. “It looked good from the outset and tillered prolifically,” says Andrew.

The ground was too wet to travel to apply a T0, so the first PGR application was applied at GS31. Moddus was applied then and at GS32, followed by 1 litre/ha of Terpal at GS37.

“The field is our most lodging-prone field, so this was a tremendous test for the Goldfinch. Of the 100 acres we planted, only one acre on the most exposed slope leaned, but it remained easy to harvest.”

A robust fungicide programme was applied to the pre-basic seed crop – had it been a commercial crop Andrew says he would have only applied a T2 due to the variety’s excellent disease resistance.

The Goldfinch averaged 10.1 t/ha and exceeded full milling specification. “This year especially, that’s a really good performance, particularly the protein at 13.7%. If this isn’t a Group 1 milling wheat I don’t know what is.”

Andrew believes RAGT’s Genserus wheat breeding programme marks a major step forward in wheat production. “I think this trait is critical. If we can have wheats that require no insecticide at all, that is IPM at its absolute best.

“This has been a low-insect year here, yet Goldfinch has still delivered financially. I estimate I’m £60/ha better off in terms of production costs, and it’s hit milling spec across the board with plenty of yield.”

-

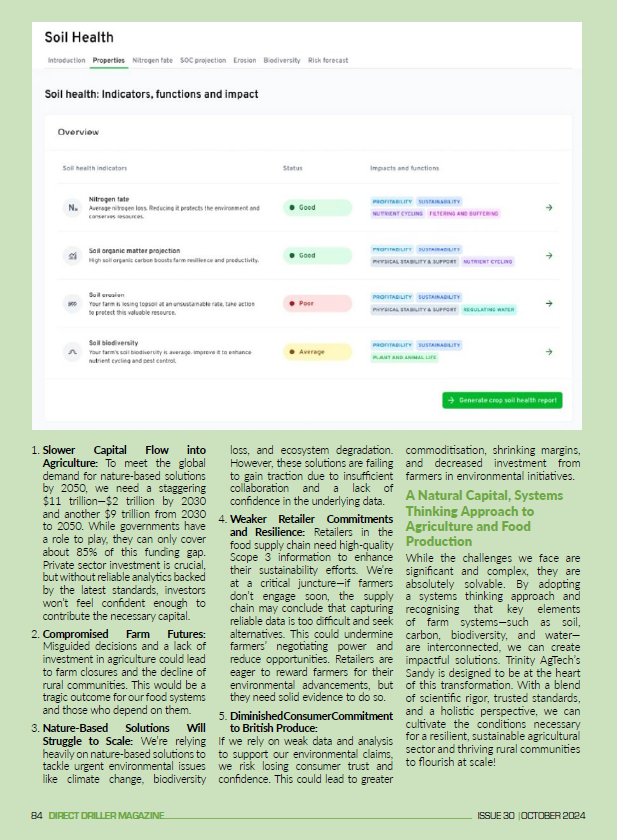

Why scientific credibility and standards compliance are vital for farming and rural communities

Find out why scientific credibility and standards compliant natural capital analytics are critical for farming and rural communities

Written by Anna Woodley from Trinity AgTech

Agriculture is evolving in ways we’ve never seen before, needing to address both challenges and exciting opportunities. It’s been made crucial for us to rethink how we approach these changes. Clinging to old perspectives and methods won’t cut it anymore; we need a fresh outlook and new ways that truly reflects the realities we’re all facing. We know that navigating the unknown can be intimidating, and it’s natural to want familiarity. Some of us might consider taking the easier route or stick to old ways, hoping things will just get better on their own. But history shows us that we can’t go back to simpler times; big change is here, and now part of our journey. By embracing these complexities with open minds, we will adapt and agricultural business can thrive.

At Trinity, we believe in aiming high rather than settling for less. Our focus is on utilising rigorous, yet user-friendly analytics grounded in the latest credible science and standards rather than choosing short-cuts and cutting corners. The answer lies in the complexity of farming itself. Agriculture is a dynamic web where soil health, carbon sequestration, biodiversity, and water cycles are intricately connected, each influencing the others and impacting broader ecosystem services. For farmers and stakeholders, overlooking these complexities can lead to poor decisions, wasted resources, and missed opportunities for profitable and sustainable farming.

By adopting a systems-thinking approach, we recognise that farms natural assets, each with its own intricacies, don’t operate in isolation. It’s vital to understand how changes in soil carbon, for example, can affect biodiversity, water retention and yields. Without applying rigorous science to credibly evaluate, measure and monitor these dynamics and interdependencies, our hopes for effective and efficient outcomes for farming and rural communities will fall flat.

While it’s tempting to gravitate toward short-cuts; vanity project and box-ticking will do injustice to the inherent complexity of agriculture and will ultimately compromise the livelihood of our farming communities. The rigor and credibility of the science we use and the rigor and consistency of our methods across a farm’s natural assets, provide the necessary foundation to unlock the full potential of on-farm production now and confidently bestow a healthy legacy to the future generations. Without it, we risk everything, undermining the resilience of our farms, hindering cost management, and limiting investment opportunities, all of which are essential for securing our food and farming future.

Why are standards so critically important when assessing on-farm carbon and natural capital?

There’s a common misconception that natural capital assessments, particularly for carbon, lack standardised methods. This is simply not true and is a perpetuated falsehood which often stems from an unwillingness to work through the complexity, scientific delivery and digital mechanisms required to appropriately meet the requirement of those high standards. In reality, globally recognised standards—like ISO 14064-2, ISO 14067, and the Greenhouse Gas Protocol’s Land Sector and Removals Guidance—play a crucial role in ensuring that carbon and ecosystem service assessments are robust and comparable. These frameworks provide a solid scientific foundation, allowing the natural capital space to grow with integrity.

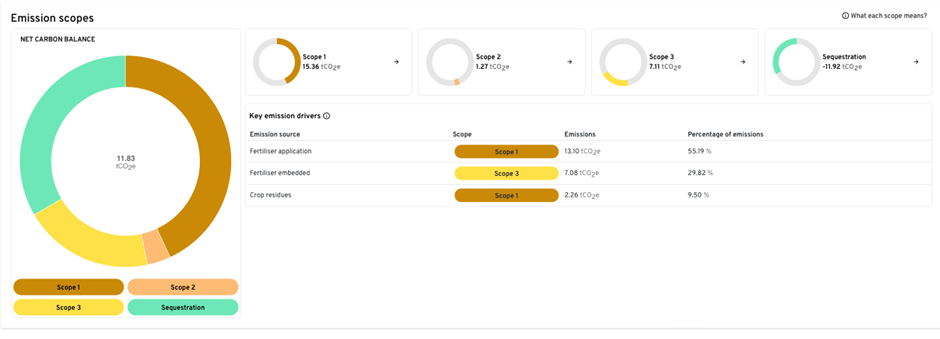

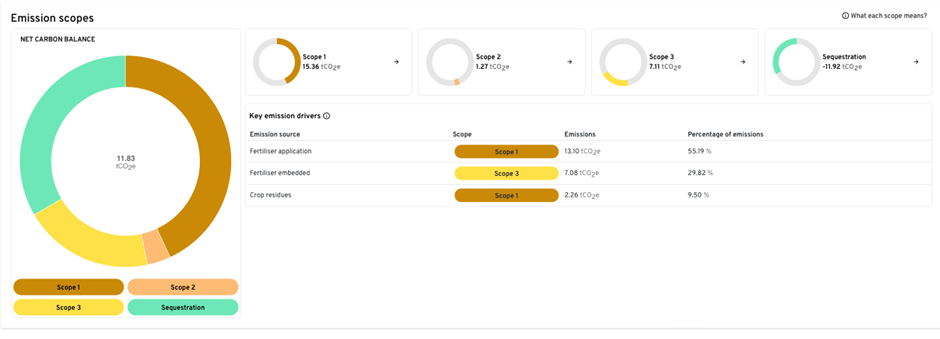

For instance, by aligning with initiatives like the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) and the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi), we can create the certainty needed to attract private sector investment in agriculture. These standards help bridge the gap between agronomic realities and financial markets, enabling investors to make informed decisions about where to allocate their resources. This means farmers can access the tools they need to improve their operations, while stakeholders throughout the food supply chain can trust that the farm’s productive health as well as sustainability efforts are based on credible analytics. As we know, ultimately, adhering to high-quality standards isn’t just a technical necessity—it’s essential for building at-scale trust, credibility, and investment.

Businesses across the food supply chain are increasingly committing to these standards, with ALDI recently announcing their support for SBTi FLAG. National and international standards ensure that any analysis of natural capital aligns with the latest science and methodologies, guaranteeing high quality and integrity. Trinity’s Sandy platform stands out as the only carbon and natural capital assessment tool that adheres to all these standards and reporting requirements.

Internal Health and Performance of Farm Businesses

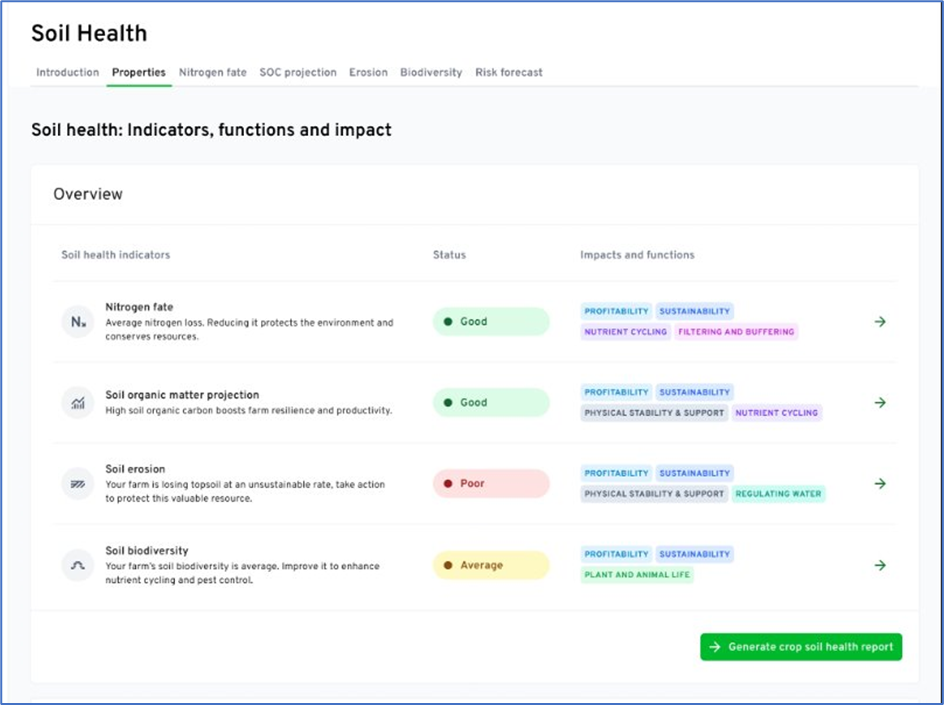

In today’s complex and volatile environment, farmers urgently need credible insights into the health of their businesses, particularly regarding their natural capital utilization, its overall health and value, and their income-generating capacity. We now understand that assessing the health of a farm isn’t just about tracking traditional financial metrics; it’s also about evaluating natural assets—like soil, water, and biodiversity—that are crucial for productivity. Natural capital provides essential ecosystem services for food production, from pollination to water filtration. Farmers need reliable assessments of these assets to manage risks, optimise inputs, and maintain resilient, productive farming systems.

A systems-thinking approach helps us see how a farm’s natural capital health is closely linked to its economic health. For example, poor soil health can lower yields, increasing reliance on synthetic inputs that may degrade biodiversity and water quality. By taking a holistic view of business health that considers these interconnections, farmers can enhance their long-term sustainability and resilience against challenges like soil erosion and flood risk.

Accurately assessing a farm’s natural capital—covering carbon, soil health, biodiversity, and water—is essential for farmers to gain a clear picture of their operations, manage risks effectively, and make informed decisions. With farm businesses facing unprecedented vulnerabilities, optimizing decision-making for resilience in our food supply chain and financially thriving rural communities is more crucial than ever.

Transparency and Disclosure in Environmental Reporting

Maintaining scientific credibility, recognised standards, and consistency across natural assets provides the necessary integrity and assurance for all stakeholders to benefit. Aligning with globally recognised standards, such as those outlined in Defra’s ‘Harmonisation of Carbon Accounting Tools’ report, is a vital step. This alignment fosters collaboration among stakeholders—banks, private investors, retailers, farmers, and policymakers—allowing us to tackle challenges at scale, unlock investment in agriculture, and achieve positive outcomes for everyone.

Transparency is key to facilitating capital flow into agriculture. Private investors, policymakers, and other stakeholders need to know that their investments are driving measurable, verifiable, and scalable results, effectively mitigating the risk of greenwashing. Together, we can build a stronger, more sustainable agricultural future!

If we rely on vanity reporting and use low-quality natural capital data and analytics, we expose ourselves to significant risks:

- Slower Capital Flow into Agriculture: To meet the global demand for nature-based solutions by 2050, we need a staggering $11 trillion—$2 trillion by 2030 and another $9 trillion from 2030 to 2050. While governments have a role to play, they can only cover about 85% of this funding gap. Private sector investment is crucial, but without reliable analytics backed by the latest standards, investors won’t feel confident enough to contribute the necessary capital.

- Compromised Farm Futures: Misguided decisions and a lack of investment in agriculture could lead to farm closures and the decline of rural communities. This would be a tragic outcome for our food systems and those who depend on them.

- Nature-Based Solutions Will Struggle to Scale: We’re relying heavily on nature-based solutions to tackle urgent environmental issues like climate change, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem degradation. However, these solutions are failing to gain traction due to insufficient collaboration and a lack of confidence in the underlying data.

- Weaker Retailer Commitments and Resilience: Retailers in the food supply chain need high-quality Scope 3 information to enhance their sustainability efforts. We’re at a critical juncture—if farmers don’t engage soon, the supply chain may conclude that capturing reliable data is too difficult and seek alternatives. This could undermine farmers’ negotiating power and reduce opportunities. Retailers are eager to reward farmers for their environmental advancements, but they need solid evidence to do so.

- Diminished Consumer Commitment to British Produce: If we rely on weak data and analysis to support our environmental claims, we risk losing consumer trust and confidence. This could lead to greater commoditisation, shrinking margins, and decreased investment from farmers in environmental initiatives.

A Natural Capital, Systems Thinking Approach to Agriculture and Food Production

While the challenges we face are significant and complex, they are absolutely solvable. By adopting a systems thinking approach and recognising that key elements of farm systems—such as soil, carbon, biodiversity, and water—are interconnected, we can create impactful solutions. Trinity AgTech’s Sandy is designed to be at the heart of this transformation. With a blend of scientific rigor, trusted standards, and a holistic perspective, we can cultivate the conditions necessary for a resilient, sustainable agricultural sector and thriving rural communities to flourish at scale!

To find out more about our unique approach to nature-based solutions, contact our team.

-

Securing sustainability

A move to biological seed treatments has helped a Borders grower move away from chemical alternatives in a bid to help secure long-term business sustainability and improve soil health.

Written by Sarah Ferrie from Interagro

Though sustainability has become a buzzword in farming over recent years, for many growers making strategical decisions across their operations to promote long-term viability is an integral part of their ethos. This may mean looking at establishment techniques, chemical inputs and what alternative tools are in the armoury.

Biologicals and biostimulants are among those alternative tools that have gained a huge amount of traction over recent years, with large amounts of research and development going into products to prove they’re more than just ‘muck and magic’.

So are biostimulants the next logical step on the industry journey to sustainability? David Fuller-Shapcott thinks so. Farming 369ha in the Scottish Borders near Roxburghshire, David has spent the past few years looking at how to refine and improve his business. This has included being part of the YEN network, which saw him win the bronze award for best percentage of potential yield in oilseed rape in 2019 and another oilseed rape bronze award for yield in 2022.

“We’re farming mostly heavy clay, high magnesium soils which are very sticky when wet but like concrete when dry,” says David. “I’ve been focusing on soil health for a while, but now we’re trying to nuance that – refine that focus – to improve the proportion of soil fungi, which is one of the main reasons I’m not very keen on putting fungicidal seed dressings on the crop. Though I’ve been told they have no effect, I have difficulty believing that a fungicide in the soil doesn’t influence fungi populations.”

It’s this reason that one of David’s main goals for the farm is to reduce his dependence on chemicals. “To enable this, we need to make sure that the seed we plant is healthy – everything starts with the seed. One of the things that chemicals have bought in the past is rooting benefits, but I’m looking at what else is out there to provide the same advantages.”

Alternative options

This is where biostimulants have proved to be a good alternative option, with David particularly finding success from using Newton – an organic plant-based biostimulant treatment from Interagro which is claimed to aid both crop establishment and to build healthier, stronger plants which are more resilient in the face of stress factors such as drought. “One of the main ingredients within Newton is signalling peptides,” explains Interagro’s technical manager, Stuart Sutherland. “These peptides are essentially signalling messengers for plants to modify their hormonal balance to reduce stress and enhance quality and quantity production parts in plants.”

But what does this mean practically for farmers? Stuart says the high loading of peptides within Newton means incorporation can help with regulation of both plant growth and development which in turn can lead to faster seed germination and emergence.

This has been proven in a number of independent trials over recent years, he adds. “These trials have shown that by including Newton, growers can not only speed up crop emergence by several days but can also help build tolerance against stress by triggering key defence mechanisms and even reduce the reliance on synthetic fertilisers by increasing rooting ability.”

Tried and tested

David tested Newton for the first time two years ago, putting it up against Kick Off – a phosphate-based seed treatment designed to help boost rooting – incorporated with a fungicide. “I trialled it in a field of spring barley, sowing 56m wide strips and comparing paired tramlines of Newton with paired tramlines of Kick Off.

“I then asked the agronomist to see if he could find any difference,” recalls David. “I told him where the breaks were in the tramlines, but not what the products were, and he could not find a single difference between the fungicide and Kick Off tramlines and where Newton was used alone.

“What we took from that is that Newton was bringing a fair bit to the party in terms of how it benefited crop performance, and also reducing my seed costs as a consequence. We took this through to combine yield at harvest over a weighbridge and found no statistical difference in yield either, so now I just use Newton alone. I don’t bother with Kick Off or SPDs in the spring – Newton does it all.”

This season, all of David’s spring barley was sown with Newton only and he’s looking to do some Newton-only autumn sowing later this year. “My spring barley has all been direct drilled for the first time this year with the Newton and it got away fine – I’ve not suffered with any moisture stress which a lot of spring barley in the area has. Generally speaking, it looks well.

“With my YEN hat on, it’s very clear that we need to be enhancing rooting to maximise output – rooting is imperative to both water and nutrient capture – and as a treatment, Newton ticks that box well. Using it means my nitrogen use efficiency has improved because rooting and water capture has got better, therefore I’ve not been suffering in these dry springs we’ve been having recently.”

David notes that he sees the spring being a particularly beneficial timing for the application of Newton. “These dry springs seem to be getting more common, so I think Newton will have a really big role to play prior to this window to help bolster plant resilience.”

Future plans

Looking to the future, sustainability is the goal. “Short-term, this means focusing on getting direct drilling to work for us which is difficult in Scotland, on water-retentive soils and weather patterns like we’ve been having,” explains David. “Long-term, I want to be in a position where we are – or fairly close to being – net zero and we’re recognised for that. I think that’s a key part of this, being recognised that what we can do as farmers makes us part of the solution and not the problem.

“Biologicals will be a key component in achieving this – they’re absolutely part of the IPM approach to how we grow crops. We’re losing chemicals, either regulatory or efficacy wise, at an alarming rate and we’ve got to get on the front foot and understand what we can do to improve the way we’re growing crops.

“Newton is a piece of the jigsaw, with a number of tabs on that piece, which fit into a lot of other aspects of crop production – which is where we need to be if we’re aiming to achieve true resilience.”

NEWTON FAQS

- Composition: vegetable-derived peptides

- Recommended crops: cereals, peas, beans

- Recommended rate: 1 litre/tonne of seed

- Compatibility: Compatible with chemical and nutritional seed dressings

- Application: Can be applied to seed via a conventional seed treater or mobile

- Approved for use in organic systems by OF&G and registered with the Soil Association

-

Land sparing and land sharing – considerations for farming with nature

Written by Dr David Cutress: IBERS, Aberystwyth University.

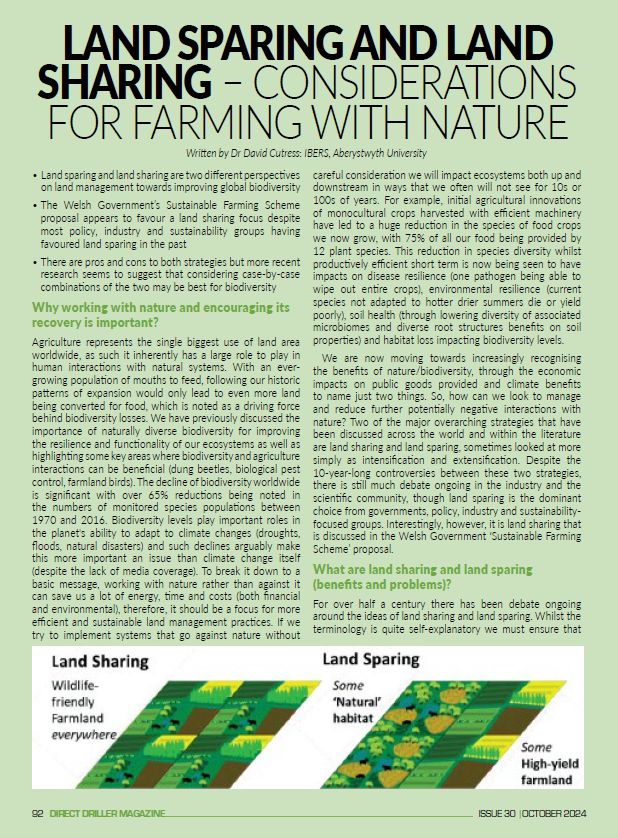

- Land sparing and land sharing are two different perspectives on land management towards improving global biodiversity

- The Welsh Government’s Sustainable Farming Scheme proposal appears to favour a land sharing focus despite most policy, industry and sustainability groups having favoured land sparing in the past

- There are pros and cons to both strategies but more recent research seems to suggest that considering case-by-case combinations of the two may be best for biodiversity

Why working with nature and encouraging its recovery is important?

Agriculture represents the single biggest use of land area worldwide, as such it inherently has a large role to play in human interactions with natural systems. With an ever-growing population of mouths to feed, following our historic patterns of expansion would only lead to even more land being converted for food, which is noted as a driving force behind biodiversity losses.

We have previously discussed the importance of naturally diverse biodiversity for improving the resilience and functionality of our ecosystems as well as highlighting some key areas where biodiversity and agriculture interactions can be beneficial (dung beetles, biological pest control, farmland birds). The decline of biodiversity worldwide is significant with over 65% reductions being noted in the numbers of monitored species populations between 1970 and 2016. Biodiversity levels play important roles in the planet’s ability to adapt to climate changes (droughts, floods, natural disasters) and such declines arguably make this more important an issue than climate change itself (despite the lack of media coverage).

To break it down to a basic message, working with nature rather than against it can save us a lot of energy, time and costs (both financial and environmental), therefore, it should be a focus for more efficient and sustainable land management practices. If we try to implement systems that go against nature without careful consideration we will impact ecosystems both up and downstream in ways that we often will not see for 10s or 100s of years.

For example, initial agricultural innovations of monocultural crops harvested with efficient machinery have led to a huge reduction in the species of food crops we now grow, with 75% of all our food being provided by 12 plant species. This reduction in species diversity whilst productively efficient short term is now being seen to have impacts on disease resilience (one pathogen being able to wipe out entire crops), environmental resilience (current species not adapted to hotter drier summers die or yield poorly), soil health (through lowering diversity of associated microbiomes and diverse root structures benefits on soil properties) and habitat loss impacting biodiversity levels.

We are now moving towards increasingly recognising the benefits of nature/biodiversity, through the economic impacts on public goods provided and climate benefits to name just two things. So, how can we look to manage and reduce further potentially negative interactions with nature?

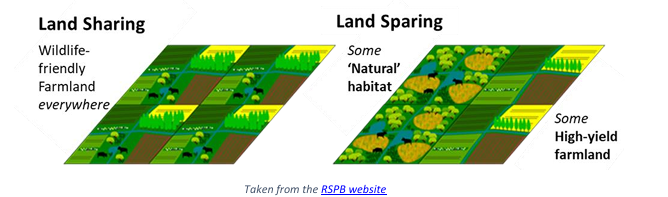

Two of the major overarching strategies that have been discussed across the world and within the literature are land sharing and land sparing, sometimes looked at more simply as intensification and extensification. Despite the 10-year-long controversies between these two strategies, there is still much debate ongoing in the industry and the scientific community, though land sparing is the dominant choice from governments, policy, industry and sustainability-focused groups. Interestingly, however, it is land sharing that is discussed in the Welsh Government ‘Sustainable Farming Scheme’ proposal.

What are land sharing and land sparing (benefits and problems)?

For over half a century there has been debate ongoing around the ideas of land sharing and land sparing. Whilst the terminology is quite self-explanatory we must ensure that the aspects of these two options are understood before we discuss them further. Land sparing involves the consideration that we can merge all of our production needs into fewer highly intensive/efficient smaller areas, ‘sparing’ the remainder of the land (particularly important conservation/protection regions like rain forests and nature reserves) to be utilised for natural biodiversity-friendly ecosystems.

Land sharing on the other hand involves shifting the focus to less intensive more sustainable farming and land management systems across current land space to increase natural mimicry and lead to biodiversity increases across all lands at the same time. Land sparing could have a lot of benefits as it potentially involves less complicated considerations surrounding the recovery and functionality of highly complex natural ecosystems within the land that is ‘spared’ as once established these will require minimal management.

It is often focused on by governments as it can make a country appear far more sustainable depending on the metrics being measured. What land sparing is specifically beneficial for, is conserving species-rich habitats which are often those focused on for protection in sparing strategies, which often contain species with very small global ranges.

However, if land sparing is not considered globally and holistically it can simply lead to the shift of ecosystem/nature impacts elsewhere in the world and, therefore, realistically have no real beneficial impact. For example, if livestock facilities are intensified down to smaller areas and are high-producing systems they will likely require huge feed imports which may simply end up offshoring the issue of monoculture climate-negative crops, such as palm oil and soya.

Similarly, if ecosystems are made the focus then there may be further insufficient land for food production, increasing a nation’s reliance on, and the costs and emissions associated with, food importation. Consolidation of products into smaller intensive spaces may also have negative impacts on farmers’ abilities to spread their investments/risks which should not be overlooked. A concept often linked with land sparing which farmers find controversial is ‘rewilding’. Many believe re-wilding to be a waste of productive land which could otherwise be turning a profit, but it is important to note that subsidies are increasingly available that can make strategies which encourage natural biodiversity increases more beneficial.

Equally many ecosystems are now so degraded or far removed from historic natural states that they cannot easily self-repair without land management assistance, therefore, there could be roles for farmers and land managers to play in the future to be properly reimbursed by sustainability-focused subsidies to assist the ecological restoration of spared lands. Whilst this may benefit innovative, forward-thinking individuals, it of course does act as a barrier to integration for farmers who wish to simply farm as they always have and not re-skill to being ecosystem caretakers.

Land sharing was proposed as a methodology where many individuals do smaller amounts to benefit biodiversity as a whole, and largely many of the techniques associated are already being taken up within the concept of sustainable farming systems which encourage biodiversity.

The extensification that occurs can allow farmers and land managers to spread their production, therefore, spreading their potential yield risks to ensure at least some gains if there are crop or pasture failures. For this concept to work, it requires a change in focus from yields achieved to biodiversity gains, as such it doesn’t answer the consumer needs adequately without a shift from the consumers towards, for example, reduced meat eating and reduced food waste in general.

Whilst both these consumer changes would equally benefit land sparing they are more prominent for land sharing. Furthermore, many early models suggest that land sharing alone would ultimately reduce biodiversity more on the lands that would need to be encroached on (to feed the growing population) than it would improve biodiversity on the lands already being used, leading to a skewed impact.

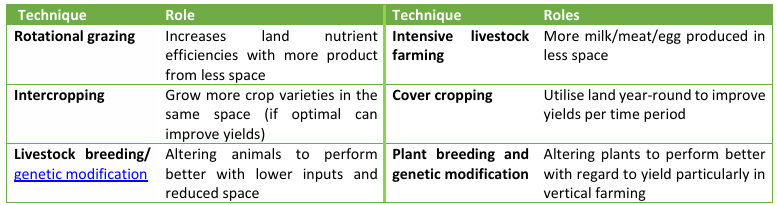

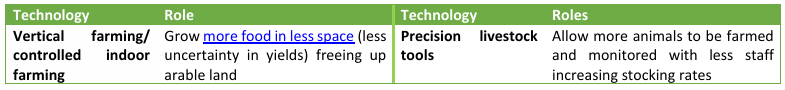

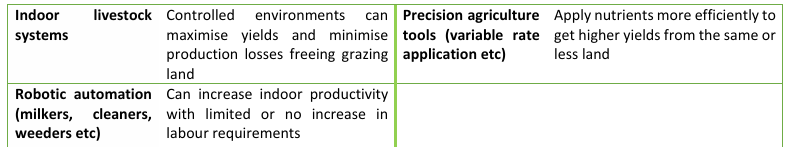

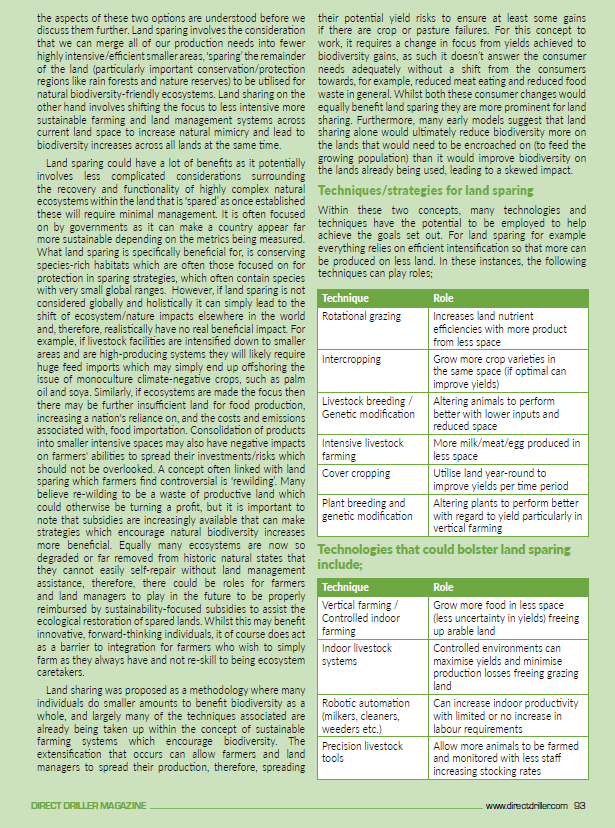

Techniques/strategies for land sparing

Within these two concepts, many technologies and techniques have the potential to be employed to help achieve the goals set out. For land sparing for example everything relies on efficient intensification so that more can be produced on less land. In these instances, the following techniques can play roles;

Technologies that could bolster land sparing include;

Whilst these technologies can all benefit more products from less space they may not do so with energy-saving/environmental and animal wellbeing benefits as their key focus.

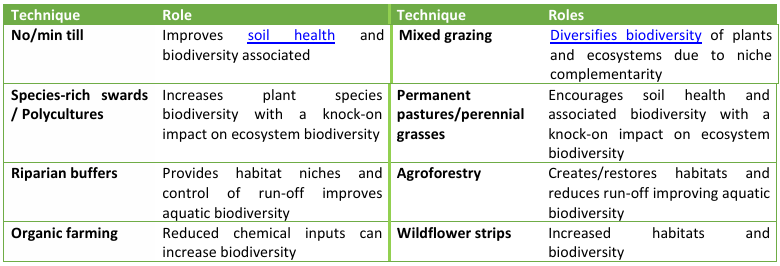

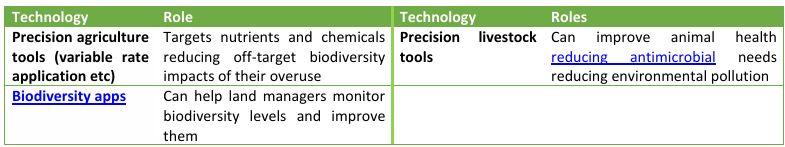

Techniques/strategies for land sharing

Land sharing techniques, on the other hand, are far more related to our previous discussions on sustainable farming and regenerative farming as both focus on improving biodiversity within their concepts.

Some technologies overlap between the two strategies depending on their focus and how they are used.

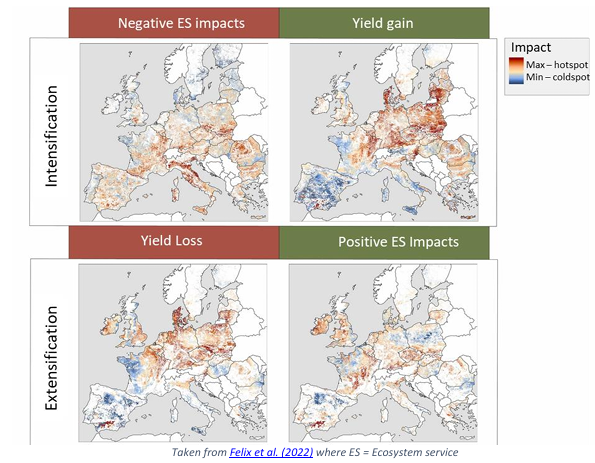

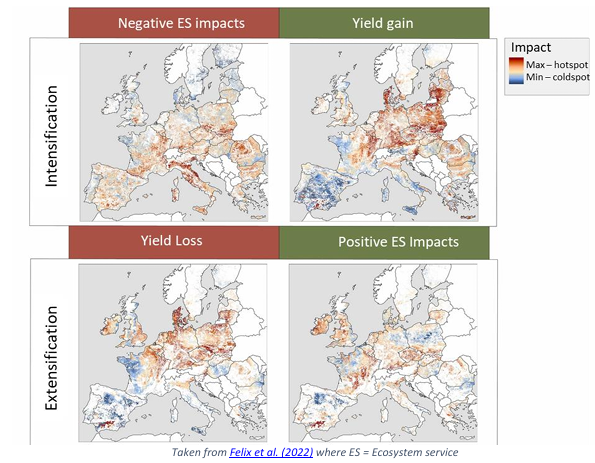

Why not both?

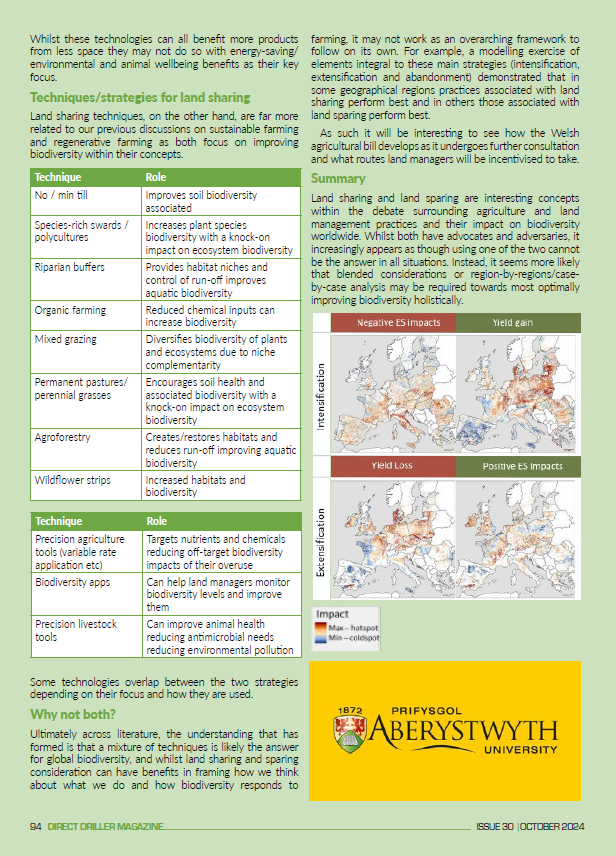

Ultimately across literature, the understanding that has formed is that a mixture of techniques is likely the answer for global biodiversity, and whilst land sharing and sparing consideration can have benefits in framing how we think about what we do and how biodiversity responds to farming, it may not work as an overarching framework to follow on its own. For example, a modelling exercise of elements integral to these main strategies (intensification, extensification and abandonment) demonstrated that in some geographical regions practices associated with land sharing perform best and in others those associated with land sparing perform best.

As such it will be interesting to see how the Welsh agricultural bill develops as it undergoes further consultation and what routes land managers will be incentivised to take.

Summary

Land sharing and land sparing are interesting concepts within the debate surrounding agriculture and land management practices and their impact on biodiversity worldwide. Whilst both have advocates and adversaries, it increasingly appears as though using one of the two cannot be the answer in all situations. Instead, it seems more likely that blended considerations or region-by-regions/case-by-case analysis may be required towards most optimally improving biodiversity holistically.

-

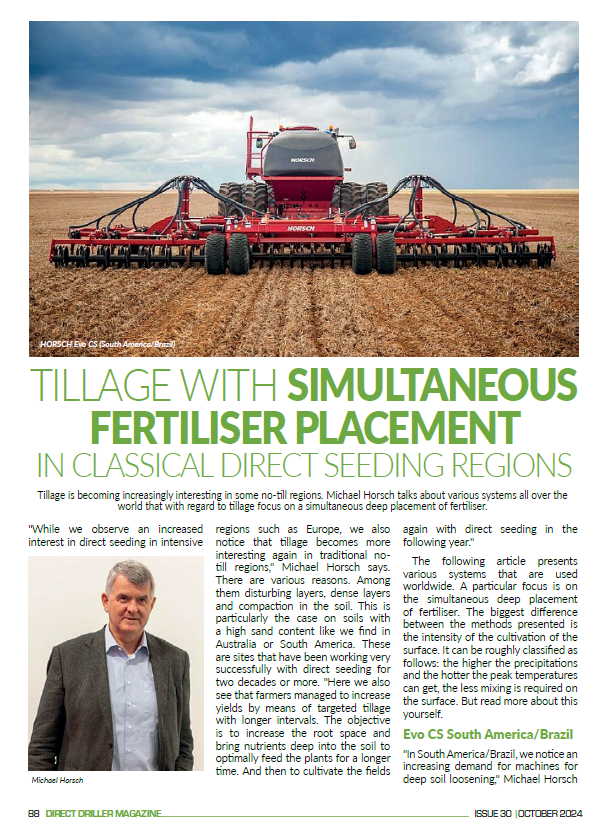

Tillage with simultaneous fertiliser placement in classical direct seeding regions

Tillage is becoming increasingly interesting in some no-till regions. Michael Horsch talks about various systems all over the world that with regard to tillage focus on a simultaneous deep placement of fertiliser.

“While we observe an increased interest in direct seeding in intensive regions such as Europe, we also notice that tillage becomes more interesting again in traditional no-till regions,” Michael Horsch says. There are various reasons. Among them disturbing layers, dense layers and compaction in the soil. This is particularly the case on soils with a high sand content like we find in Australia or South America. These are sites that have been working very successfully with direct seeding for two decades or more. “Here we also see that farmers managed to increase yields by means of targeted tillage with longer intervals. The objective is to increase the root space and bring nutrients deep into the soil to optimally feed the plants for a longer time. And then to cultivate the fields again with direct seeding in the following year.”

HORSCH Evo CS (South America/Brazil) The following article presents various systems that are used worldwide. A particular focus is on the simultaneous deep placement of fertiliser. The biggest difference between the methods presented is the intensity of the cultivation of the surface. It can be roughly classified as follows: the higher the precipitations and the hotter the peak temperatures can get, the less mixing is required on the surface. But read more about this yourself.

Michael Horsch

Evo CS South America/Brazil

“In South America/Brazil, we notice an increasing demand for machines for deep soil loosening,” Michael Horsch says. The objective is to loosen the soil deeply to break layers that have formed over several decades of direct seeding. These layers act like compactions and prevent further root penetration. In most cases, the reason is the washing in of fine soil particles from the surface and, on lighter sites, the dense compaction of sand. In regions with high rainfall and high biological activity, the objective is loosening without surface mixing. “These are the regions where we mainly sell the Evo CS and now also the Evo TL. The use of fertiliser is always possible and is also requested by the customers. In most cases, this is phosphorus, but we also notice more and more discussions about placing lime deeper in the soil.”

Fertiliser is placed across almost the full working depth. This allows for applying fresh nutrients, especially phosphorus and potash, to the soil in a targeted way. Fertiliser can be applied at two levels, with the option of changing and individually adapting the respective dose. In Brazil, the Evo CS is not used as a standard tool, but rather for the targeted improvement of fields where usually direct seeding is used. Equipped with a packer system, it leaves behind a closed surface.Tiger MT with FertiProf Ukraine

In one single pass, the Tiger MT can mix in a lot of organic material and, in the Ukraine, is therefore mainly used after grain maize and sunflowers. The objective is to achieve a reasonable mixing ratio so that the straw can decompose during the vegetation period. In one pass, the Tiger MT manages to mix intensively, to loosen and level the soil as well as to consolidate it to achieve a horizon that is ready for seeding. The advantage of mixing is that the straw is in a more intensive contact with the soil and, thus, decomposes more reliably.

HORSCH Tiger MT with FertiProf (Ukraine)

In combination with the FertiProf attachment, fertiliser can be placed directly in the depot. The obvious advantage is that the fertiliser is applied in deeper layers where water is potentially available for a longer time, thus allowing for a longer uptake of nutrients as the soil dries off from above. This means that the water is available for a longer time for nutrient uptake. This effect plays a decisive role for phosphate in particular, but also for potassium in combination with heavy soils. Moreover, the plant specifically looks for phosphorus concentrations. This ensures that root penetration takes place. The third advantage of concentrating fertiliser is to create a small-scale saturation of the soil so that the nutrients are longer available to the plant. The black earth soils of the Ukraine are ideal for the concentrated placement of fertiliser, as nutrient supply is scarce, as they time and again are dry during the season and have a very high exchange capacity.

Tiger MT Australia

The approach pursued with the use of the Tiger MT in Australia aims to mix organic material into the partly sandy soils and deeply loosen the ground. Fine material on the surface is washed in by rainfall, forming compacted layers over the years. Initial experience shows that breaking these compacted layers has positive effects, while simultaneously leveling and re-compacting the soil with the Tiger MT helps prevent new compacted layers from forming. The primary goal is to maximize water absorption after rainfall and increase its availability for crops. In combination with a MiniDrill, the Tiger is also used to plant cover crops.

HORSCH Tiger MT (Australia)

Panther USA

Starting around 2007, the HORSCH Panther (then the HORSCH Anderson 60-15) started being used for autumn fertiliser operation in North Dakota and South Dakota. This system has grown in popularity since then and today is a common autumn fertiliser application system used by contractors and farmers alike in these regions. Compared to traditional strip till on 30” row spacing, the Panther system utilises its existing 15” shank spacing for fertiliser application. Narrow openers are installed for use with fertilizer sources of dry, liquid, or NH3 and even a combination of products at the same time. The overall concept of the Panther gives several agronomic advantages when being used for fall fertilizer applications.

The Panther has proven itself in the broadacre min-till/no-till type farming systems of the northern corn belt of North America. The opener system can place fertilizer 8 to 15 cm deep with minimum soil disturbance. A cutting coulter system is used in front of each shank to prevent plugging in heavy residue conditions. Surface level residue stays relatively intact. Usually, the Panther travels a slight angle to the direction of planting. This gives uniform coverage over the field, eliminates the need for RTK steering at planting, is independent of planter row spacing, plus provides an amount of soil loosening/mixing to break shallow soil compaction.

HORSCH Panther (USA)

Field conditioning is another agronomic topic with the Panther system. When applying fertilizer, the strips are closed and firmed, not leaving a ridge or berm. The disc levelling system and pneumatic tire packing system leave the field smooth for planting in the spring. This closing and firming action also aids in securing NH3, sealing the strip to prevent gas-off losses. The added benefit is with the soil movement and disc levers, small ruts from harvest get levelled. Some farmers will do a shallow pass of spring seedbed preparation, others will leave a stale seedbed.

With the Panther system there is large capacity for carrying dry fertilizer and also towing NH3 trailers. A very simple system, in the northern corn growing regions the results have been positive. Yield results in corn have been comparable to typical 30” strip till systems. Further north into western Canada the Panther is being used on a true 15” spacing of fall fertilizer strips then spring planting of canola and wheat. In addition, the Panther can be converted between seeding applications and fertilizer applications, adding to the versatility for farmers maximizing return on investment of the unit.Phosphorus and potassium dynamics in the soil

The availability of phosphorus in the soil can roughly be divided into three parts. Stable phosphate is bound to calcium, iron, aluminium or in organic matter and is not available to the plant. Unstable phosphate is characterised by a more or less strong sorption to exchangers such as clay minerals, oxides or organic compounds. Dissolved phosphate is present in the soil solution as free and immediately plant-available HPO42-. The balance of these three fractions in the soil very quickly flows towards the stable phosphorus and also quickly and severely restricts the availability of fertilised phosphorus to the plant. This process is also referred to as phosphorus ageing and is very difficult to reverse. The concentration of dissolved phosphate is very low with an average of 1-2 mg/l and requires soil moisture, soil temperature, good basic phosphate supply and optimum soil reactions (pH value, microbial activity, root exudates) for sufficient replenishment. A high humus content increases the share of unstable phosphate and thus promotes the availability as well as a good root penetration by the crop.

Phosphorus is involved in all energy metabolic processes in the plant and is particularly important for root formation and the storage of starch in the grain.

Phosphate that is stored in a depot is sorbed as usual at the contact surfaces of the depot with the soil environment until the bonds are saturated. The majority of this soluble phosphate inside the depot thus remains fully available to the plant over a longer period of time.

The uptake of nutrients via the mass flow requires water. As only very small doses of phosphorus are present in the soil solution, the mass flow alone is not sufficient. The additional diffusion requires significantly more water. Thus, the uptake of phosphate suffers in dry conditions. Placing the depot in a deeper layer that is more likely to bear water increases the uptake reliability. As unstable and stable phosphate are not prone to wash out and as soluble phosphate is present in low concentrations, the risk of a displacement to even deeper layers is low. In rare cases, if it is extracted continuously from the subsoil without deeper, replenishing mixing, this immobility of phosphate can even be disadvantageous in dry periods.

High magnesium contents favour the uptake of phosphorus. Iron and zinc mobility within the plant is restricted if the phosphorus content is high. A high nitrate supply also restricts the uptake of phosphorus.

In contrast to phosphorus, potassium is much more mobile in the soil. The three fractions are also found in potassium. However, the potassium content in the soil of up to over 100,000 kg per hectare in the top 30 cm of the topsoil are enormous. The strength of the bond to clay particles, organic matter and to minerals and salts varies and ensures a constant supply and, due to the high solubility of potassium, an easy washing out on light soils. The availability is limited by the K saturation at the exchanger (correct ratio of calcium, magnesium and potassium), the soil structure and the depth as well as by antagonisms among others with ammonium. The higher the content of potassium-fixing clay particles, the stronger the bond and the lower the risk of washing out. After many years of extraction, clayey soils with mainly expandable clay minerals (smectite or the transformation to illite) tend to fix potassium immediately after fertilisation.

The fertilised potassium is stored in the intermediate layers of the clay minerals and is no longer available until these layers are replenished. As the ion diameters of K+ and NH4+ are similar, ammonium is sometimes also incorporated in these empty layers. “Fresh potassium” can displace ammonium and ensure that nitrogen is replenished.

Potassium influences the regulation of water uptake via the roots which also influences the supply of nutrients and their distribution within the plant parts. In dry conditions, it is responsible for the proper closing of the stomata and thus prevents further drying out. Barley and sugar beet react much more sensitively to the lack of potassium than for example wheat.

Due to its high mobility and the good solubility, the short-term top fertilisation of potassium also makes sense. Well-supplied soils with a high clay content react somewhat slowlier to top fertilisation than sandy soils. In the case of poorly supplied clayey soils, recognisable by the low soluble potassium content even after fertilisation, top fertilisation is not practicable. In this case, the plant has to be supplied via a concentrated fertiliser band. The resulting “micelle” saturates the adjacent clay minerals and remains available to the plant in the core.Focus (StripTill)

The Focus works according to the StripTill principle where the soil is only cultivated in the seed rows. Due to the front tine zone, the soil is loosened in strips and removes crop residues from the seed and root zone. The loosening depth can vary depending on the soil. The Focus offers various options for fertiliser application. In addition to a 100% application directly into the loosened root zone resp. on the topsoil, there is also the option of a proportional 50:50 application. This allows for responding to different conditions when seeding. In very good seeding conditions, the placement at the cultivation depth allows for supplying the lower topsoil area with fresh nutrients in a targeted way. If the conditions are rather wet and cold, the 50:50 placement can be used to specifically encourage the crop’s youth development and “lure” the roots downwards. This attraction effect makes the plant significantly more drought-resistant as it can form roots more quickly and efficiently in deep layers.

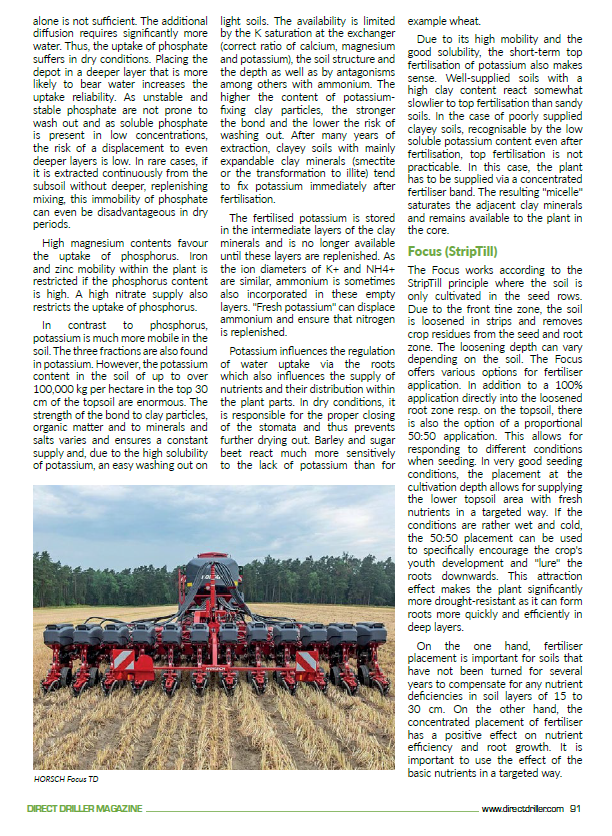

HORSCH Focus TD

On the one hand, fertiliser placement is important for soils that have not been turned for several years to compensate for any nutrient deficiencies in soil layers of 15 to 30 cm. On the other hand, the concentrated placement of fertiliser has a positive effect on nutrient efficiency and root growth. It is important to use the effect of the basic nutrients in a targeted way.

-

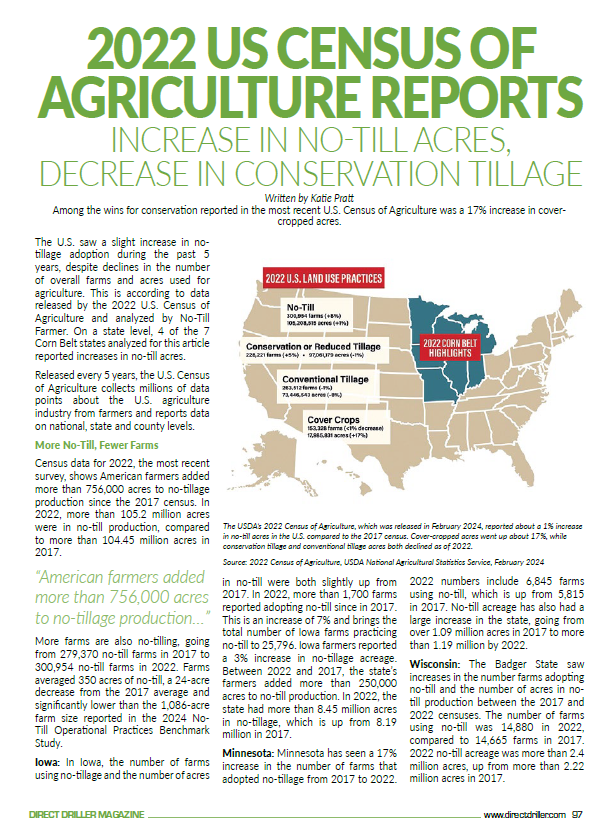

2022 US Census of Agriculture Reports Increase in No-Till Acres, Decrease in Conservation Tillage

Among the wins for conservation reported in the most recent U.S. Census of Agriculture was a 17% increase in cover-cropped acres.

By Katie Pratt from No-till Farmer USA

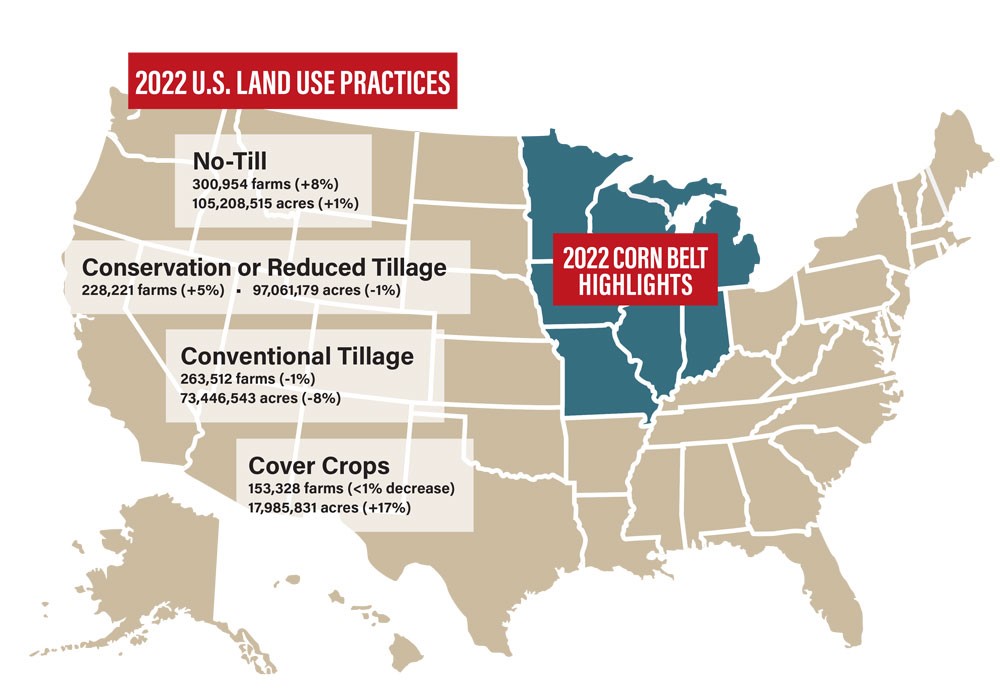

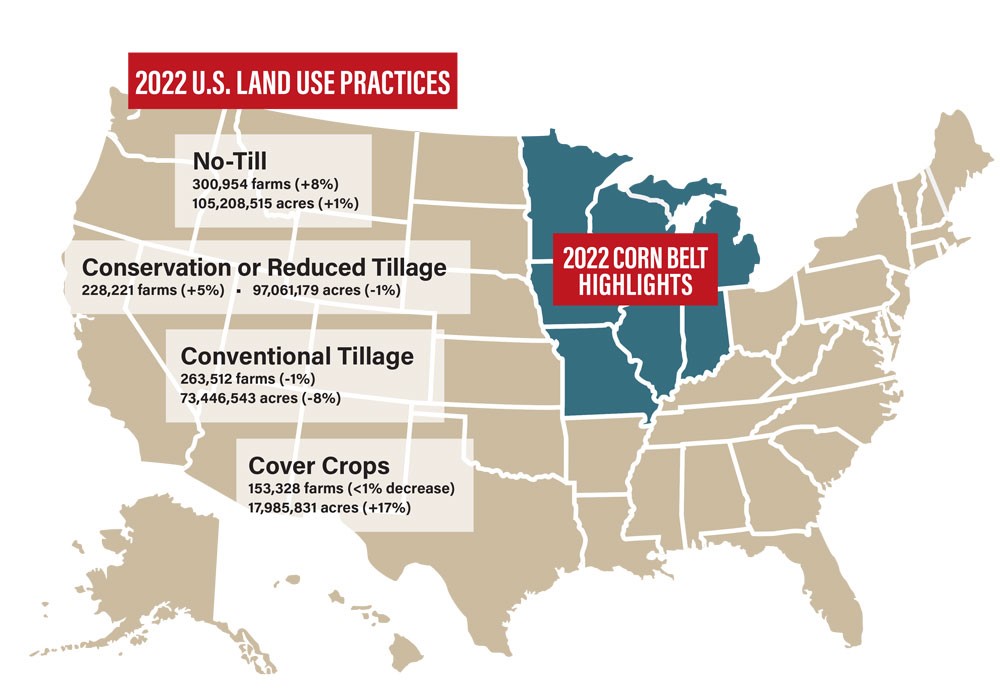

The U.S. saw a slight increase in no-tillage adoption during the past 5 years, despite declines in the number of overall farms and acres used for agriculture. This is according to data released by the 2022 U.S. Census of Agriculture and analyzed by No-Till Farmer. On a state level, 4 of the 7 Corn Belt states analyzed for this article reported increases in no-till acres.

Released every 5 years, the U.S. Census of Agriculture collects millions of data points about the U.S. agriculture industry from farmers and reports data on national, state and county levels.

More No-Till, Fewer Farms

Census data for 2022, the most recent survey, shows American farmers added more than 756,000 acres to no-tillage production since the 2017 census. In 2022, more than 105.2 million acres were in no-till production, compared to more than 104.45 million acres in 2017.

More farms are also no-tilling, going from 279,370 no-till farms in 2017 to 300,954 no-till farms in 2022. Farms averaged 350 acres of no-till, a 24-acre decrease from the 2017 average and significantly lower than the 1,086-acre farm size reported in the 2024 No-Till Operational Practices Benchmark Study.

Iowa: In Iowa, the number of farms using no-tillage and the number of acres in no-till were both slightly up from 2017. In 2022, more than 1,700 farms reported adopting no-till since in 2017. This is an increase of 7% and brings the total number of Iowa farms practicing no-till to 25,796. Iowa farmers reported a 3% increase in no-tillage acreage. Between 2022 and 2017, the state’s farmers added more than 250,000 acres to no-till production. In 2022, the state had more than 8.45 million acres in no-tillage, which is up from 8.19 million in 2017.

Minnesota: Minnesota has seen a 17% increase in the number of farms that adopted no-tillage from 2017 to 2022. 2022 numbers include 6,845 farms using no-till, which is up from 5,815 in 2017. No-till acreage has also had a large increase in the state, going from over 1.09 million acres in 2017 to more than 1.19 million by 2022.

Wisconsin: The Badger State saw increases in the number farms adopting no-till and the number of acres in no-till production between the 2017 and 2022 censuses. The number of farms using no-till was 14,880 in 2022, compared to 14,665 farms in 2017. 2022 no-till acreage was more than 2.4 million acres, up from more than 2.22 million acres in 2017.

Michigan: The number of no-till farms and acres have declined over 5 years. In 2022, Michigan farmers reported more than 1.38 million no-till acres on 7,896 farms, which are decreases of 11% and 3%, respectively. In 2017, the state’s farmers no-tilled over 1.56 million acres on 8,174 farms.

Indiana: The Hoosier State saw drops in the number of farms and acres using no-tillage between 2022 and 2017. In 2022, producers reported 14,892 no-till farms and about no-till 4.72 million acres. This is down from 15,867 farms and more than 4.9 million acres in no-tillage in 2017. These are declines of 6% and 3%, respectively.

Missouri: The Show Me State saw increases in the number of farms and no-till acres from 2017 to 2022. Missouri farmers reported a 6% increase in the number of farms with no-tillage acres 2022 for a total of 15,490 farms. In 2017, the state had 14,555 farms practicing no-till. Acreage is up by 5% with farmers adding 250,000 more no-till acres in the 5 years between the two censuses. This increase brings total no-till acreage in the state to 4.89 million in 2022, up from 4.64 million in 2017.

Illinois: Illinois saw a slight decrease in the number of farms and the number of acres in no-till production over 5 years. In 2017, more than 6.47 million acres and 21,979 farms used no-tillage. In 2022, farmers reported 21,631 farms and more than 6.43 million acres in no-till.

Kansas had the most no-till acres with farmers no-tilling more than 11.74 million acres in the state, followed by Nebraska (10.1 million acres), Iowa (8.45 million acres), Montana (7.97 million acres) and North Dakota (7.8 million acres).

Census data showed the number of U.S. farms and land used for agriculture continues to decline. In 2022, there were 109,000 fewer farms and 20 million fewer acres dedicated to agriculture than in 2017. With fewer acres dedicated to agriculture, but a continuously increasing world population, experts see no-till as a solution to future challenges — and a worthy national investment.

“Ballooning disaster relief payments are another trend that the next food and farm bill can address,” says Ricardo Salvador, director of the Food and Environment Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “With crops and livestock increasingly at risk due to drought, extreme heat, heavy rains and other climate change impacts, Congress must preserve and increase funding for conservation programs that will make farms more resilient to extreme weather, reducing losses and associated insurance payouts, and safeguarding the security of the U.S. food system.”

The USDA’s 2022 Census of Agriculture, which was released in February 2024, reported about a 1% increase in no-till acres in the U.S. compared to the 2017 census. Cover-cropped acres went up about 17%, while conservation tillage and conventional tillage acres both declined as of 2022. Source: 2022 Census of Agriculture, USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service, February 2024 Conservation Tillage Acreage

More farms are using conservation or reduced tillage, but the number of acres decreased since 2017. In 2022, more than 11,000 farms added conservation or reduced tillage since 2017, a 5% increase. However, conservation or reduced tillage acreage has slightly declined from 2017’s 97.75 million acres to 97.06 million acres in 2022. It’s possible that some of those acres may have gone into no-till, as the no-till acreage increased by more than 756,000 acres since the 2017 census.

The number of U.S. farms and acres using intensive or conventional tillage continues to decline. The U.S. saw a drop of 6.55 million acres in conventional tillage from 2017 to 2022, an 8% decline. Conventional tillage also declined 24% between the 2017 and 2012 censuses. The average number of acres that each farm puts in conventional tillage also declined by 23 acres to 279 acres, a 7% drop from 2017’s 302-acre average.

As a result, more than 73% of all U.S. cropland used no-till or reduced tillage in 2022. This is up slightly from 2017 when around 72% of U.S. cropland was in no-till or reduced tillage.

U.S. farmers added cover crops to 2.5 million more acres in the past 5 years. In 2022, 17.98 million acres had a cover crop planted on them, up more than 16% from 15.39 million acres in 2017. At the farm level, the average amount of cover crop acreage per farm increased by 17 acres. The average amount of cover crops farmers plant is up to 117 in 2022 from 100 acres in 2017. These figures do not include lands that are in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). Texas leads all states with 1.55 million acres seeded to cover crops, followed by Iowa (1.28 million acres), Indiana (988,282 acres), Nebraska (925,686 acres) and Missouri (921,222 acres).

-

Stratified Soil Sampling: A New Lokk at Soil Testing

What happens to the fertiliser which is sown on or near the surface of No-till fields? After a decent shower we see it has gone, presumably disappearing to the root area. But what happens then? How far does it get into the soil profile? Have you got the answer?

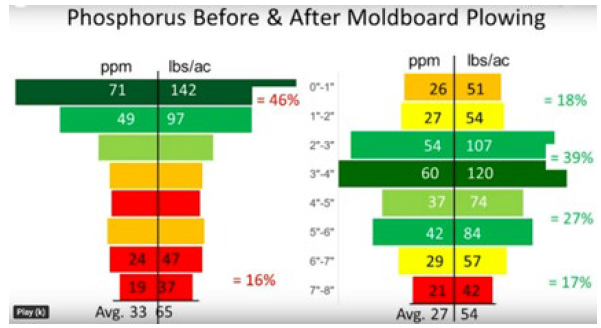

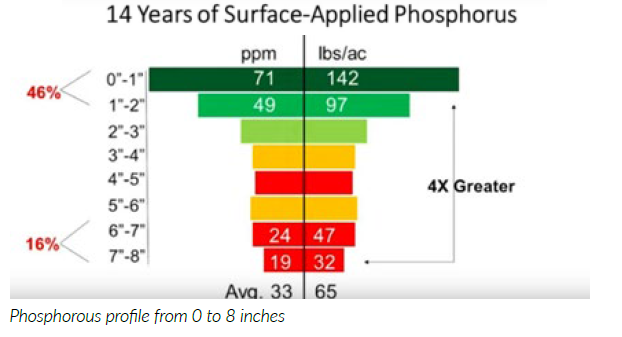

Marion Calmer from Illinois is a farmer, farming educator, innovator and maker of headers and other maize based machinery and in 2022 he decided to find out. Through ingenious soil sampling he discovered that most of the plant nutrients, which amounted to $1,000/ac over 14 years, were left in the top two inches. 42% of P was found in the top two inches, and just 16% in the bottom 6 – 8 ins slice.

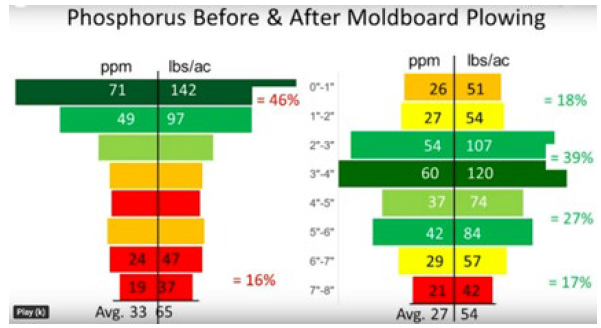

Which meant the roots stayed close to the surface, so they stopped working in a dry spell. He could see and measure the quantity of this surplus fertiliser After 14 years No-till he got out his plough and cultivator after harvest, planted cover crops in the autumn and in the spring did a deep chisel to give the soil a thorough mixing. The result was a tremendous maize crop.

At the same time he divided the soil test into one inch thick layers extending to eight inches in depth. The test sites were done where the soil differed rather than in a grid, as he wanted to see if there was a difference in plant nutrients at various depths. He found that this was very much the case.

The financial difficulties of the 1980s forced Marion Calmer to find more efficient and profitable ways of farming. After a visit to then-world-record-holder Herman Warsaw’s farm in 1985, Marion became interested in narrow row maize due to the potential yield increase and input cost reduction.

In that same year he founded Calmer Agronomic Research Centre, an independent, self-funded enterprise with the goal of discovering ways to reduce input costs and increase profitability for himself and other farmers. This involved designing and building the world’s first header used to harvest maize planted at 15 inches in 1994. In 2013 he made the first 12-inch corn head. More recently he created the BT Chopper® Upgrade Kit which is a retrofit system that enables the heads on all the top brands of harvester to manage cornstalk residue more efficiently, saving farmers time and money.

Because of his research, Marion has:

- gone from conventional tillage to no-till

- adopted the use of biotechnology

- gone from growing maize and soybeans in 40-inch rows to growing both crops in 15-inch rows

- reduced his herbicide treatments down to one pass

Marion emphasises the independence of the research done in his name, and he won’t accept any outside money for research from commercial or government bodies. He knows the data is unbiased and can be used with confidence on his farm and on others.

What happens to residual No-till fertiliser?

Farming No-till for the past 30 years has provided him a huge amount of experience, multiplied many times by seeing the results of other farmers he visits. His interest turned to the way fertiliser travelled in the soil on his farm. He came up with a way of doing soil tests at different depths or strata which would measure the weight (using American lbs) in lbs per acre of available nutrient. He took a strata from ground level to a depth of 8 inches, and measured the contents of each sample for not only P and K but pH, Ca and even Organic Matter.

The samples were taken in early November, seven months since the last application which was at drilling time, so there was no newly sown fertiliser in the soil. The measurements showed the residual which was available for the cover crop and, potentially, for the crop following. The figures clearly illustrated how the nutrients linger in the top two inches and only a small quantity get to the 7 – 8 inch strata.

The phosphate goes from 37 lbs/ac at 7-8 inches to 142 lbs at 0-1 inch depth. Between 1 and 2 ins it has dropped to 97. The same applies to potash, the surface layer carrying 569 lbs and the 7-8 bottom section 177 lbs, an increase of 223%.

Many No-till farmers assume and are told that nutrients pass through the soil structure carried by winter rains and snow, but this test shows omething very different. The photos of Marion in the three different test areas are visual evidence of the differences in growth rate. The crop n field 1 was planted without fertiliser and had reached forearm height. It had leaves yellowing in the bottom. The crop in the second test area was healthier, taller and fewer leaves affected. The third field was cultivated to mix the soil in the 8 inch zone, and so was mouldboard ploughed, broken down with a cultivator, fertilised in the autumn and chisel ploughed before planting. This crop was stronger, taller by about a ft, and advanced over the other two.

The soil sample from the ploughed land showed how the nutrients were distributed evenly with the 0-1 inch profile reading 51 lbs P/ac, followed by 54 lbs in 1-2in; 107 in 2-3; 120 in 3-4; 74 in 4-5; 84 in 5-6; 57 in 6-7 and 42 in 7-8ins depth. The plough had inverted the surface burying the nutrient into the moisture zone, putting the nutrient where it does the most good. The soil samples of each three fields were taken so to find the level of nutrients in each of the eight layers. To do this he cut them into one inch slices which were sent off for analysis. Samples were taken from the best, the median and the poorest parts of each plot in a field that has a uniform soil structure.

The maize grown without fertiliser was showing stress from the 10 week drought. The outside of the bottom leaves was yellow, indicating a deficiency in potassium. Marion points out in the video that if the yellowing occurred up the spine of the leaf the problem would be N.

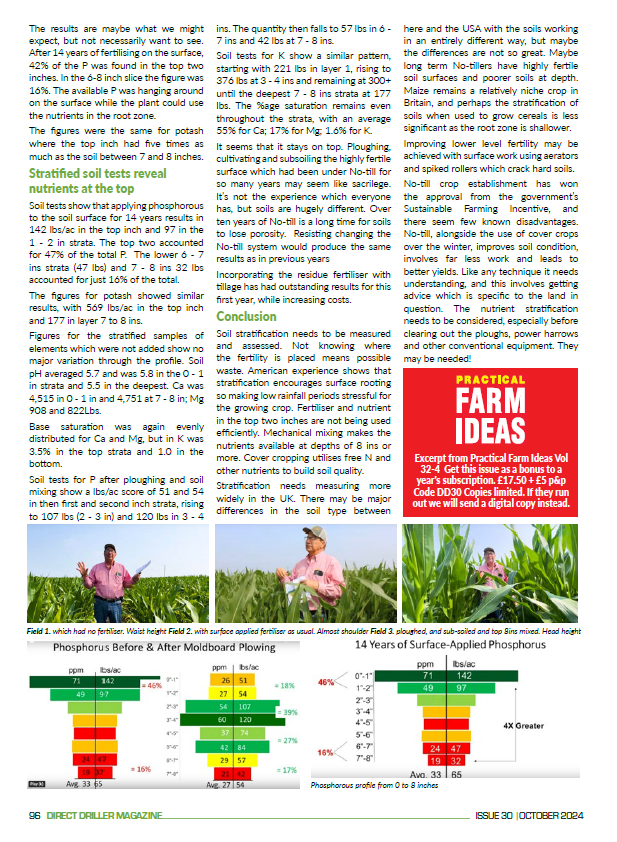

The results are maybe what we might expect, but not necessarily want to see. After 14 years of fertilising on the surface, 42% of the P was found in the top two inches. In the 6-8 inch slice the figure was 16%. The available P was hanging around on the surface while the plant could use the nutrients in the root zone. The figures were the same for potash where the top inch had five times as much as the soil between 7 and 8 inches.

Stratified soil tests reveal nutrients at the top

Soil tests show that applying phosphorous to the soil surface for 14 years results in 142 lbs/ac in the top inch and 97 in the 1 – 2 in strata. The top two accounted for 47% of the total P. The lower 6 – 7 ins strata (47 lbs) and 7 – 8 ins 32 lbs accounted for just 16% of the total. The figures for potash showed similar results, with 569 lbs/ac in the top inch and 177 in layer 7 to 8 ins. Figures for the stratified samples of elements which were not added show no major variation through the profile. Soil pH averaged 5.7 and was 5.8 in the 0 – 1 in strata and 5.5 in the deepest. Ca was 4,515 in 0 – 1 in and 4,751 at 7 – 8 in; Mg 908 and 822Lbs. Base saturation was again evenly distributed for Ca and Mg, but in K was 3.5% in the top strata and 1.0 in the bottom.

Soil tests for P after ploughing and soil mixing show a lbs/ac score of 51 and 54 in then first and second inch strata, rising to 107 lbs (2 – 3 in) and 120 lbs in 3 – 4 ins. The quantity then falls to 57 lbs in 6 – 7 ins and 42 lbs at 7 – 8 ins. Soil tests for K show a similar pattern, starting with 221 lbs in layer 1, rising to 376 lbs at 3 – 4 ins and remaining at 300+ until the deepest 7 – 8 ins strata at 177 lbs. The %age saturation remains even

throughout the strata, with an average 55% for Ca; 17% for Mg; 1.6% for K. It seems that it stays on top. Ploughing, cultivating and subsoiling the highly fertile surface which had been under No-till for so many years may seem like sacrilege.It’s not the experience which everyone has, but soils are hugely different. Over ten years of No-till is a long time for soils to lose porosity. Resisting changing the No-till system would produce the same results as in previous years Incorporating the residue fertiliser with tillage has had outstanding results for this first year, while increasing costs.

Conclusion

and assessed. Not knowing where the fertility is placed means possible waste. American experience shows that stratification encourages surface rooting so making low rainfall periods stressful for the growing crop. Fertiliser and nutrient in the top two inches are not being used

efficiently. Mechanical mixing makes the nutrients available at depths of 8 ins or more. Cover cropping utilises free N and other nutrients to build soil quality.Stratification needs measuring more widely in the UK. There may be major differences in the soil type between here and the USA with the soils working in an entirely different way, but maybe the differences are not so great. Maybe long term No-tillers have highly fertile soil surfaces and poorer soils at depth.

Maize remains a relatively niche crop in Britain, and perhaps the stratification of soils when used to grow cereals is less significant as the root zone is shallower. Improving lower level fertility may be achieved with surface work using aerators and spiked rollers which crack hard soils.

No-till crop establishment has won the approval from the government’s Sustainable Farming Incentive, and there seem few known disadvantages.No-till, alongside the use of cover crops over the winter, improves soil condition, involves far less work and leads to better yields. Like any technique it needs understanding, and this involves getting advice which is specific to the land in question. The nutrient stratification needs to be considered, especially before clearing out the ploughs, power harrows and other conventional equipment. They may be needed!

-

From Innovation to Evolution: A 16-year Journey in Direct Drilling

Written by Clive Bailye

It seems like such a long time ago now, but back in 2008 when we made the decision to stop cultivating and direct drill everything, there really wasn’t a lot of drills on the market to choose from. This made our choice relatively straightforward, but also brought compromises that often saw us heading to the farm workshop to modify and adapt what we felt was needed.

Our own previous “min-till” establishment system revolved around a single Simba solo cultivation train with a DD press. This was followed by a Vaderstad Rapid cultivator drill a few weeks later after applying glyphosate to a good weed and volunteer chit. It worked well for nearly a decade and was consistent, but it was expensive, time-consuming, high-horsepower dependent, and required lots of fuel, capital, and wearing metal, all adding to an unsustainable high fixed-cost structure.

We didn’t just rush into buying our first true direct drill without our own R&D phase. We started by using that existing Rapid drill to direct, without cultivation, at the easy points in the rotation, such as wheat after beans or OSR, where the drill’s ability to handle high levels of previous crop residue was not an issue. Although not designed to be a “direct drill,” in the right situation, it was perfectly capable of doing the job and certainly provided the proof-of-concept confidence we needed to sell those big tractors and cultivators and start direct drilling every crop.

We had also learned where the mechanical challenges would be for replacement machinery on our soil types and our rotation. In high trash situations, a drill’s ability to keep residue flowing and not block was essential, especially now as we planned to grow cover crops at every possible opportunity and drill directly into them. We found a disc-based coulter best in these situations, but we had also seen how a disc can sometimes “hairpin” straw, creating establishment and agronomic issues.

When conditions are dry, without soil loosening cultivations, penetration can be a challenge for drills not designed to work directly, resulting in a compromise to seeding depth and coverage. Conversely, when conditions are wet, smearing of the seed slot or failure to close it successfully and cover the seed can be the challenge. Mechanical and agronomic solutions to these issues have occupied my mind and those of many agricultural engineers over the years, resulting in an evolution of direct drills that today make things easier than ever, or in my case lots of farm workshop time spend chopping and tweaking existing machinery.

Back in 2008, a visit to Simon Chilles, a long-term direct drilling guru in Kent, resulted in us buying his old John Deere 750a as our first proper direct drill. These drills were a rare thing in the UK, and his 4m was the only one available at that time. I recall trying to buy parts for it from our local JD dealership, whose parts counter had no knowledge of what a “750a” even was!

Being used to the capacity of a 6m rapid, we felt more capacity was required than 4m alone, so we also bought a used Dale tine drill, feeling we had the best of both worlds in the ability to drill cover crops with the 750a discs and the Dale tine to use where hair pinning was an issue.

Both drills performed well and excelled in accurate seeding depth however, after that our first season with them both, it was clear we had seriously underestimated just how much time not cultivating would gift us. We didn’t need both drills, so we sold the Dale, imported Australian-designed row cleaners and fitted them to the 750a to deal with the hair pinning issue.

As workload increased over the next few years, the 4m was eventually changed for a new 6m which we immediately cut in half to extend the chassis and added a liquid fertilizer tank, granular applicators for Avadex and slug pellets, a split hopper for companion crops, and row cleaners, all of which features are either standard fit can be optioned from the factory on many of the drills available now. We learned in wetter seasons that a disc could smear on our soils and blocked where a tine didn’t, so we bought an old Horsch CO6 and modified it with a Bourgault VOS tines to act as insurance for such years, an investment that paid back handsomely in the very wet autumn of 2020.

Over time, we have customized our own solutions to get the machinery that we needed to consistently direct drill our soils. Meanwhile, the interest among UK farmers in direct drilling has grown significantly, and along with it, so has the choice of drills.

By the time our 750a was due for replacement, there was so much more choice of suitable machinery that didn’t need farm workshop adaptations to add options we wanted. I have become a fan of wider row widths in cereals, and with our drill tractor size dictated at a 240hp minimum to be able to pull our trailed sprayer and 18t grain trailers, it had always been too big for the 6m John Deere. The added efficiency of being able to operate a 12m Horsch Avatar with the same tractor was just too tempting. Its coulters familiar with a similar layout to the 750a and with large split hoppers, fertiliser placement all factory options, so no need for farm modifications.

My soils and my rotation will of course differ from those of others, as is always the case in farming there is no simple “copy and paste” solution that will work for all; every farm is different, and time and effort will need to be invested in researching solutions.

Experience here reflects the evolution of how the direct drill market has now created a huge choice of fantastic machinery available from so many quality manufacturers meaning a solution is now available to suit most soils and rotations.

Compared to my lack of choice 16 years ago, the question today is, how do you decide which of these many machines is right for you? Hopefully, this supplement and the QR code links to Phillip Wrights video interviews with some of the manufactures at the Cereals event this year provides a good starting point for initial comparison to help you make good, informed decisions.

-

Aitchison Seed Drills

Neil Ford from Aitchison Agri talks to Philip about the Aitchison Seedmatic ASM4020 The Seedmatic

Reap the benefits every time with the Seedmatic Series. The Seedmatic built with over five decades of proven Aitchison seeding experience in mind, the extremely successful 4000 Series Seedmatic seed drill lets you sow the seeds of success the Aitchison zero-tillage way. The Seedmatic tine drills will penetrate existing stubble or pastures, hard and rocky as well as cultivated soils.

They are commonly used to renovate or bulk up existing pastures, as well as sow crops such as wheat and clover, peas or oilseed rape into cultivated soils or direct into stubble. Renowned for building soil organic matter and creating an optimal environment for trouble free seed germination.

The Seedmatic drills have a narrow 125mm or 5 inch row spacing with 14 inch disc coulters combined with a 400mm stagger of seeding rows enabling superior residual matter clearance. The vibrating 25mm Seedmatic tines are designed with a slimline boot holder to handle trash with ease and together with the Aitchison tipped Ni-hard inverted “T” boot, giving the perfect seed to soil contact creating the perfect seeding environment.

The Seedmatic drill range is designed to deliver uniform plant emergence with optimum yields at lower costs. The unique sponge delivery seeding system is extremely accurate and the infinitely variable gearbox handles most seed volumes and sizes effortlessly. It will deliver seeds of all sizes in most seed mixes evenly. Drills are available in seed only form or seed and fertiliser format. Available in sowing widths of 2.5m and 3m. The 3m drill qualifies for the Farm Equipment Technology Fund grant. Quality products built to last Beware of imitations of this machine.

The Grassfarmer

Aitchison’s 3000 series Grassfarmer is one of the world’s most popular seed drills, specifically aimed at making even lighter work of reseeding and or renovating existing pastures and cultivated soils. These lower cost economy linkage models are ideal for first time “zero-tillers”. They have a low horse power requirement, the highly dependable Grassfarmer is engineered to exceed your expectations. The unique sponge seed delivery system is both gentle and accurate and will sow most seeds in almost any condition at rates ranging from as low as 1kg/ha up to 350kgs/ha. Ni-hard knock on/off Aitchison inverted “T” boots with are standard on all tine drill models.

The Aitchison T- Boot

The vibrating tine with the Aitchison boot creates a smear-free, cocoonshaped mini seedbed. Competing plants have their roots pruned while the inverted T-slot mixes the seeds with the soil. The seeds may be placed 1.5″ deep in the inverted T-slot where more moisture is available; however, the seed is consistently covered with only 1/4″ to 3/8″ of finely tilled soil. The key that makes the Aitchison completely different is the special design of the Aitchison boot. The bottom surface of the boot compresses a column of soil underneath the seed, which creates a “wick” to conduct moisture upwards. The unique inverted T-shaped slot retains up to eight times more moisture and three times more oxygen than other planting systems, while offering superior seed germination. The loose, tilth-like soil deposited over the seed with the Aitchison system is a poor water conductor and acts as a barrier to stop moisture from evaporating from the seedbed. Seed savings can be 25% or greater over other drills due to improved emergence. This fact is supported by independent trial results.

How inverted T slot works

The principle of the inverted T-slot is simple and effective, giving unmatched results in all situations – any surface, every soil type and all climatic conditions.

A set of discs at the front of the drill pre-slices an opening in which the T-SEM boot then passes to create the ideal seed-bed in bands.

The shoe sheds the vegetation and prunes the roots of the existing vegetation. The seed is placed on the firm base of the T-slot so that it is in good contact with the moisture rising by capillary action.

The horizontal slicing action of the wings of the shoe means that each side of the slot falls back after the tine has passed, but the chamber remains slightly open. The micro-environment thus created allows the light and moisture to enter but retains the warmth. The consistent placement of the seed in this mini-greenhouse gives optimum conditions for an even germination, and the tilth within permits rapid root development of the young seedlings.

This explains why the plant establishment is so positive, even in an often hostile environment in the presence of living vegetation, as in a pasture rejuvenation, or dying vegetation, in an arable direct-drilling context.

The Aitchison Seed Metering System