As growers grapple for grassweed solutions, Direct Driller looks at the results from the first year of on-farm trials investigating a novel way of controlling weed seeds at harvest.

Written by Charlotte Cunningham

Grassweeds are the bane of any arable farmer’s life, with control often an uphill battle when it comes to tackling particularly persistent and resistant weeds.

Low disturbance and no-till systems are thought to be particularly vulnerable to a build-up of grassweeds as the seed shed each year stays in the germination zone, with little means of control other than repeated applications of herbicide. What’s more, there’s a heavy reliance on glyphosate, raising the prospect of resistance.

In a quest to find new solutions, a group of farmers across the country have been taking part in a new research project into a novel, chemical-free method of controlling tricky grassweeds at harvest.

The project is based around the Redekop seed control unit (SCU) technology – a retrofitted mill which sits at the back of the combine. The mill processes the chaff and is proven to kill up to 98% of weed seeds as they exit, offering growers both a way of reducing reliance on chemistry and a unique opportunity to control weeds at harvest time – something not traditionally done in the UK.

The technology has been used both extensively and successfully across North America and Australia, but the UK project is the first to put it to the test in a maritime climate.

Project background

The trials have been co-ordinated by the British On-Farm Innovation Network (BOFIN) – with test protocols developed by NIAB – on three farms across the UK.

Suffolk farmer, Adam Driver headed up the first year of trials, with an SCU fitted to his Claas Lexion 8800. Adam has a historic challenge with blackgrass building up in chaff lines of his controlled-traffic farming system and hopes the technology will be able to alleviate some of the burden. “We’re farming about 2000ha of combinable crops on a no-till system. Generally, our main weed challenge is blackgrass – we’ve got massive amounts in this area and have for a long time.”

Adam tested the technology alongside Worcestershire farmer Jake Freestone, who has an SCU fitted to his John Deere S790i in a bid to tackle meadow brome, and Warwickshire grower and Velcourt farm manager Ted Holmes, who has been trialling a unit fitted to his New Holland CR9.90 and suffers particularly with Italian ryegrass.

Year one results

Though the data set so far is small and only based on one harvest’s worth of results, there were some interesting findings from the first year’s trial, says NIAB’s Will Smith who designed its monitoring protocols and carried out the analysis on the weeds left standing at harvest.

At Adam’s farm, the headline result is that 54% of blackgrass seed was retained in winter wheat. This came as a slight surprise and was a much higher level than previously thought, admits Will.

Brome levels were also significantly reduced thanks to the use of the SCU. “I deliberately planted some winter barley in a field I know has got a lot of brome, and I haven’t found much at all,” says Adam.

While ryegrass has not typically been an issue at the farm, Adam says this is something he has seen in small amounts this year – opening up another control opportunity for the technology. “Ryegrass is something I really, really do not want here – so I’m hoping that this is something that the seed control unit will just take care of based on what we’ve seen already.”

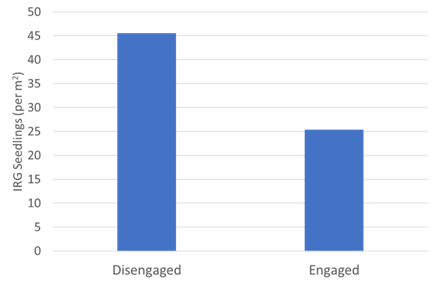

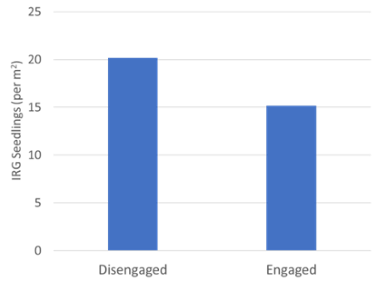

In Warwickshire, the SCU technology enabled a 60% reduction of Italian ryegrass in winter barley and 44% in spring barley, compared with using the combine alone, which was a really positive result, says Ted.

Data was limited at Jake’s farm, though weed burdens in general were lower last year, he says.

Next steps

Building on the results of last year’s trials, Adam is leading a project that has been awarded funding from the Defra Farming Innovation Programme, delivered by Innovate UK, to continue the research under Defra’s research starter round two competition.

The three farmers from the first year of the trials will be taking part again and will be joined by Keith Challen of Belvoir Farming Company who will have the SCU unit fitted to his Fendt Ideal combine. “It has become obvious that a lot of the grassweeds we’re seeing are banded behind the combine,” says Keith. “So, to be able to control those from the combine makes a lot of sense.”

Further trials will also be taking place looking at the interaction between harvest weed seed control and cultivation strategy, led by Adam. This will involve comparing his normal no-till approach with a light cultivation to see if there is any difference in chit.

Though the effectiveness of the technology as a standalone is well-proven, the results in the field are based upon exposure to weed seed. Therefore, one of the key aims of the study going forward is to collect data on seed shed of UK-specific weed challenges – something which has been fairly limited to date, explains Will. “To use harvest weed seed control strategies, you must have seeds remaining on the heads to target. Therefore, gaining a better understanding of weed seed shed patterns is vital to proper implementation of these techniques.”

As such, the research team, co-ordinated again by BOFIN, are calling for more farmers to get involved in the project by becoming a ‘Seed Scout’. This involves collecting weed samples, assessing them via one of three simple assigned methods, and then returning the seeds to NIAB for validation. The results of this will form the UK’s first farmer-led survey of grassweeds left standing at harvest. “To accelerate the project even further, we want to collect spatially diverse data about weed seed shed across a range of weed species, in a range of crops,” notes Will.

“Therefore, we’re asking farmers to go out into the field pre-harvest or the day of harvest to collect 20 heads of the weed seed heads they’re particularly concerned with and carry out a short analysis, based on an assigned methodology. This could be counting seed heads or a visual assessment of perceived weed seed shed, for example. These samples will then be sent into us at NIAB to provide further validation and analysis. We don’t anticipate this being overly complicated or time consuming during what we know is already a busy time of year.”

Will is particularly keen that those who direct drill get involved with the project. “There’s a theory that harvest weed seed control can help no-till systems more as it reduces the risk of building up a large, shallow weed seedbank. This is where interaction with Seed Scouts will be key to tease out and explore elements of a very different approach to controlling grassweeds,” he notes.

Farmers who sign up will receive an information pack containing a guide to sampling methodology and the weed seed shedding survey to record weed status and management practices. As well as this, the pack also contains 20 small envelopes for the seed samples and a postage-paid envelope to return to NIAB. “This project and the data collection associated with it has the potential to develop some really unique and novel data which will help not only growers in the UK but also the wider industry, to ensure we’re using the right tools in the right place when it comes to tackling weed management.”

Harvest seed weed control results summary:

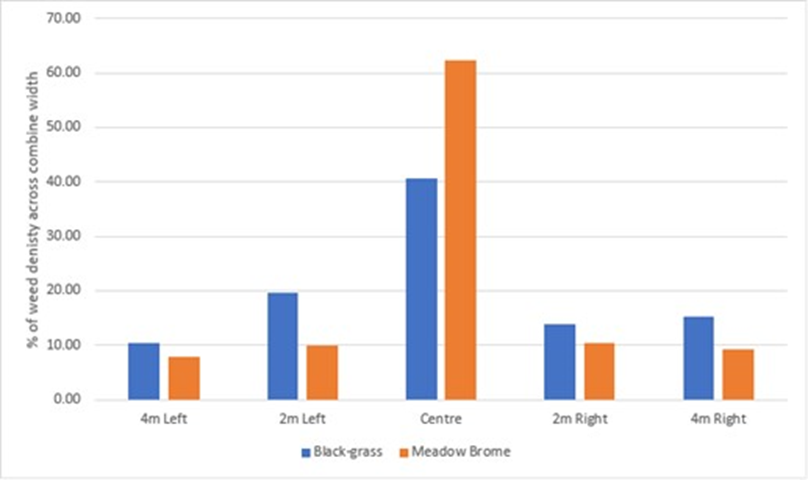

Driver Farms, Suffolk: 54% of blackgrass seed retained in winter wheat, brome populations significantly reduced. Weed counts taken by Will in the field in late October showed that for both blackgrass and meadow brome, germination follows a classic ‘bell curve’, tracking exactly the combine runs in the CTF system.

“Over 60% of the meadow brome and 40% of the blackgrass was found directly behind where the combine had passed, showing it puts the seed into the chaff stream,” he reports. “This is really important in no-till CTF systems because there’s a cumulative effect of this seed rain on the soil surface year after year.”

CAPTION: Source: NIAB, 2022; analysis carried out at Driver Farms, Suffolk, on 6 Oct in winter wheat across the 12m swath width behind the combine following winter wheat. Average of 15 points along a 150m transect.

Velcourt Farms, Warwickshire: 60% Italian ryegrass reduction in winter barley; 44% reduction in spring barley with the SCU technology.

CAPTION: Source: NIAB, 2022, Warwickshire. IRG seed shed into winter barley (left) and spring barley (right), with emerged seedlings counted on 26 October in oilseed rape and winter beans respectively. Note: the spring barley field was subsoiled, which may have introduced more seed from previous years. Figures shown are averages across two strips in each field, with multiple transects taken in each strip.