Written by Joe Stanley from the Allerton Project

‘I know it isn’t the sexiest subject, but…’ is invariably where any mention of agricultural field drainage begins, invariably accompanied by an apologetic shrug of the shoulders and a gaze cast toward the ground. Personally, I take the opposite view. I have always been fascinated by field drainage, that remarkable, invisible system of gravity-operated pipes which operate silently beneath out feet, invisible even where they empty into the humble field ditch, given that their outfalls are generally half-submerged by silt or hidden behind tussocky grass and bramble. Seven days a week and 365 days a year, field drains are silently doing their thing and continuing to return on capital invested decades – even centuries before.

I was born in the mid-1980s, just as the grants which had been made available in the post-war period came to an end. In that period, 50-60 per cent grants had seen annual installations peak at 110,000ha in the mid-1970s, with more than one million hectares of drainage installed or renewed between 1971 and 1985 alone. One of my earliest memories is watching a giant tracked vehicle installing a drain across what I would one day learn was our heaviest, least productive arable field on the family farm. From that day on, no new drainage work has ever been carried out on my farm. This is reflected in the national figures, with the amount of agricultural field drainage dropping by some 90 per cent from the 1980s to the 1990s, a level at which it has largely since remained.

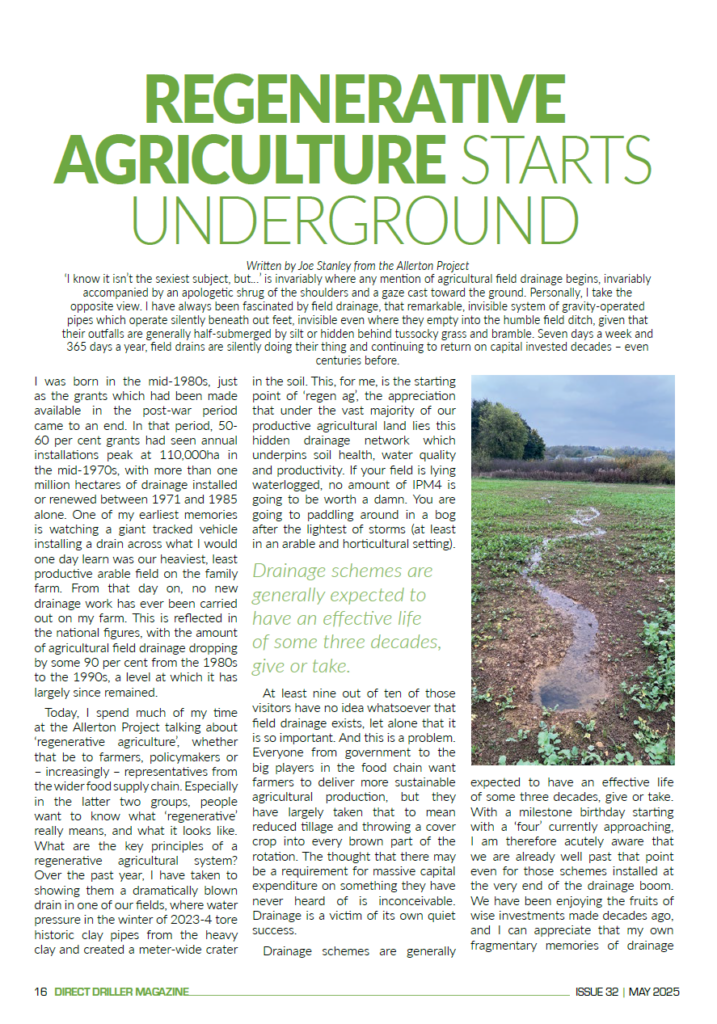

Today, I spend much of my time at the Allerton Project talking about ‘regenerative agriculture’, whether that be to farmers, policymakers or – increasingly – representatives from the wider food supply chain. Especially in the latter two groups, people want to know what ‘regenerative’ really means, and what it looks like. What are the key principles of a regenerative agricultural system? Over the past year, I have taken to showing them a dramatically blown drain in one of our fields, where water pressure in the winter of 2023-4 tore historic clay pipes from the heavy clay and created a meter-wide crater in the soil. This, for me, is the starting point of ‘regen ag’, the appreciation that under the vast majority of our productive agricultural land lies this hidden drainage network which underpins soil health, water quality and productivity. If your field is lying waterlogged, no amount of IPM4 is going to be worth a damn. You are going to paddling around in a bog after the lightest of storms (at least in an arable and horticultural setting).

At least nine out of ten of those visitors have no idea whatsoever that field drainage exists, let alone that it is so important. And this is a problem. Everyone from government to the big players in the food chain want farmers to deliver more sustainable agricultural production, but they have largely taken that to mean reduced tillage and throwing a cover crop into every brown part of the rotation. The thought that there may be a requirement for massive capital expenditure on something they have never heard of is inconceivable. Drainage is a victim of its own quiet success.

Drainage schemes are generally expected to have an effective life of some three decades, give or take. With a milestone birthday starting with a ‘four’ currently approaching, I am therefore acutely aware that we are already well past that point even for those schemes installed at the very end of the drainage boom. We have been enjoying the fruits of wise investments made decades ago, and I can appreciate that my own fragmentary memories of drainage installation must be very different to those of older generations who will remember the radical step-change in field performance rendered by the historic programme of works conducted in the decades following the end of the Second World War. And the efforts required to implement them. It is a stain on many farm businesses that basic maintenance of drains and ditches was largely neglected after the effort and cost required to install them. When I returned home in the 2010s, I was baffled as to why almost every ditch on the farm was full. Yes, the declining agricultural workforce and general expansion of farm size in recent decades had put ever-more requirements on ever-fewer people, but still, neglecting drains and ditches is a false economy if ever I’ve seen one.

We are, therefore, approaching a drainage cliff edge. Drains silt up or become packed with roots in the best of circumstances, in time. But ever-heavier machinery, deeper implements and soil erosion have led to much damage in recent years, while climate change means that many systems simply don’t have the capacity to cope with winter storm events. There’s only so far a ‘patch and mend’ approach can take us.

The logistical and financial challenge of replacing and upgrading much of the existing agricultural drainage network is a task on a gargantuan scale. In 1982, the average cost of field drainage was some £60/ha which in today’s money would be around £210/ha. Today, the real terms increase in that cost is some ten-to-seventeen times, with no grants available. With some 30 per cent of English farms making a loss in 2023-4 according to the latest Defra figures, and another 25 per cent making less than £25,000, clearly we aren’t going to be able to fund the investment required from cashflow in the current economic model. What’s more, with the recent change to APR, any investment in such value-adding measures would in fact increase tax liability. But as ever, smaller and especially tenanted farms are least able to invest in expensive infrastructure improvements.

And yet, this is not something we can just ignore. Farming on heavy silt-clay land at the Allerton Project, establishing crops in sub-optimal ground conditions is something which I am having to become used to as a default setting. In such circumstances, under-drained areas are far more visible than they used to be, especially wherever a wheel has passed. As winters become wetter, the situation will only become more challenging as existing drainage systems become increasingly compromised. This is an issue which needs to rise up the political and commercial agenda.

Admittedly, we now have somewhat different imperatives to the ‘production at all costs’ agenda of the post-war period, and no doubt there was land drained (like that final field of my own experience) which today might be better used for other purposes (whether agricultural, as grassland, or in some manner of habitat or wetland), but the fact remains that for both production and environmental reasons, field drainage is vital: waterlogging leads to both more greenhouse gas emissions from mineral soil, but also to surface runoff and erosion of sediment, nutrients and pesticides. The use of bioreactors – sumps which can use wood chip or biochar to soak up such runoff – may be the new gold standard of drainage. Government might not want to hear it, but an investment in drainage is an investment in both food security and our legally binding environmental and climate targets.

At the Allerton Project, we are currently trying to secure interest in a modern field scale drainage trial to demonstrate all the benefits of effective field drainage, with an eye to making the case to both policymakers and the supply chain about the issues raised in this piece. For too long, we’ve stood on the shoulders of past generations, generations who understood the importance of planning for and investing in the long-term, and taking the fruits of that for granted. That is a mindset that we need to get back to today.