If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

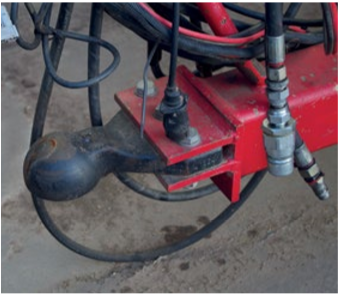

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Cover crops for integrated weed management

Cover crops can suppress weeds and volunteers by competing for light, water and nutrients. Some species also release chemicals that inhibit weed development.

Carefully managed cover crops can suppress weeds through various means. The effect varies depending on the cover crop and the weed species:

- They add diversity to the rotation and reduce opportunities for weeds to adapt to a cropping pattern

- Several cover crop types can out-compete weeds and help provide a cleaner seedbed

- Management practices associated with growing cover crops (e.g. mowing and grazing) can suppress weeds

- Long-term leys, with a lack of soil disturbance, can reduce viable seed numbers

- Some brassicas contain high levels of chemicals that can sterilise soil

Note: Make sure cover crops do not seed and become weeds. For example, phacelia can self-seed prolifically and become a weed.

Weed competition

Cover crops can compete with weeds for light, water, and nutrients.

- Increased competitive ability is linked to early emergence, seedling vigour, rapid growth, and canopy closure

- When establishing the following crop, ensure cover is uniform and minimise soil disturbance

- Some cover crops work by allowing weeds to become established and then destroyed before they produce viable seed. In this situation, cover crop canopies need to be open enough for weed germination

A note on black-grass

Cover crops only have a small impact on black-grass. Agronomic factors, such as cultivation timing and type, use and timing of glyphosate, date of crop establishment and diversity of rotation, have a bigger effect on black-grass populations. A change in the timing of crop establishment has the greatest impact.

Allelopathy

Allelopathy is where chemicals produced by one plant (or plant-associated microorganisms) affect the growth and development of another plant. The release of allelochemicals can be affected by plant age and vigour, environmental factors and the presence of other plants.

The impact of these chemicals is affected by soil texture, organic matter, temperature, light and microbial breakdown. Some plant species secrete chemicals into the soil (both during their life and after incorporation) that inhibit weed seed germination. Sometimes, these can also inhibit germination in subsequent crops, especially directly sown (i.e. not transplanted) small-seeded crops; the effect can last for several weeks.

Cover crops reported to have in-field allelopathic effects include rye, oats, barley, wheat, triticale, brassicas (oilseed rape, mustard species, radishes), buckwheat, clovers, sorghum, hairy vetch, sunflowers and fescues. However, it is not easy to separate physical competition and allelopathic effects.

Cover crops for integrated pest management

Cover crops can disrupt pest life cycles and reduce their populations. Brassicas are also used as a biofumigant to manage some soilborne pests. Certain crop species can also be used as trap crops and to encourage beneficial organisms.

Cover crops contribute to integrated pest management (IPM) through a variety of mechanisms.

Biofumigation

When certain cover crop material is chopped up and incorporated into the ground, it releases toxic compounds that help sterilise the soil. For example, brassica cover crops release glucosinolates – and products of their degradation, such as isothiocyanates – as well as volatile sulphur compounds that are toxic to many soilborne pests. Biofumigant cover crops have been demonstrated to be useful for managing beet cyst nematodes and rhizoctonia root rot in sugar beet and potato cyst nematodes in potatoes.

How cover crops are produced, destroyed and incorporated will affect the efficacy of biofumigation.

Biofumigation for PCN management

Trap crops and host disruption

Some cover crops can act as a trap crop by promoting pest egg hatch, including some nematode species.

Cabbage root fly and other brassica pests can be disrupted by diverse planting, for example, with intercropped cover crops (understory or strips). However, the approach requires experimentation in each system.

Predator habitat

Cover crops provide habitats for general predators, which is especially important over the winter.

Summer-flowering plants also encourage beneficial predators such as hoverflies, lacewings and parasitic wasps.

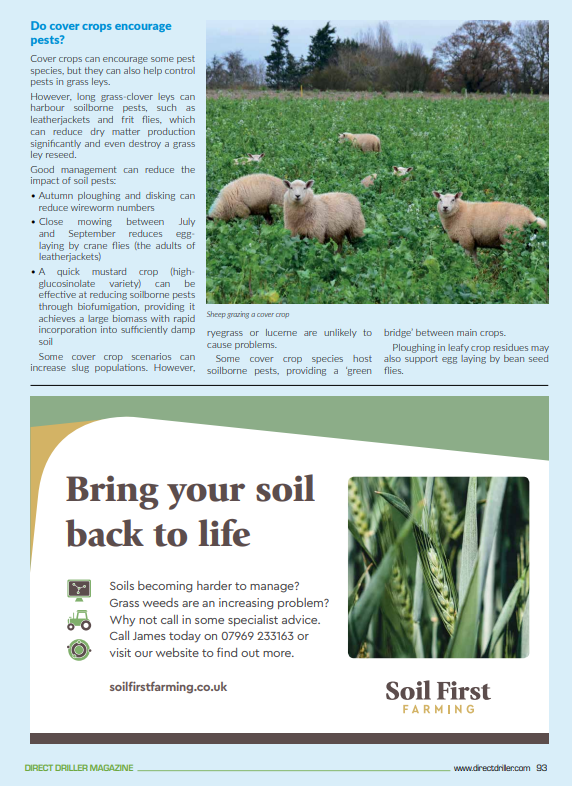

Do cover crops encourage pests?

Cover crops can encourage some pest species, but they can also help control pests in grass leys. However, long grass-clover leys can harbour soilborne pests, such as leatherjackets and frit flies, which can reduce dry matter production significantly and even destroy a grass ley reseed.

Good management can reduce the impact of soil pests:

- Autumn ploughing and disking can reduce wireworm numbers

- Close mowing between July and September reduces egg-laying by crane flies (the adults of leatherjackets)

- A quick mustard crop (high-glucosinolate variety) can be effective at reducing soilborne pests through biofumigation, providing it achieves a large biomass with rapid incorporation into sufficiently damp soil

Some cover crop scenarios can increase slug populations. However, ryegrass or lucerne are unlikely to cause problems. Some cover crop species host soilborne pests, providing a ‘green bridge’ between main crops. Ploughing in leafy crop residues may also support egg laying by bean seed flies.

-

Bayer and Trinity Agtech join forces to drive regenerative practices in agriculture

Bayer’s European Carbon Initiative enables farmers, food processors and retailers to achieve carbon commitments and implement regenerative agriculture practices. By 2025, Bayer expects to significantly increase the number of food and ag value chain projects and the number of participating farmers / Trinity Agtech’s Sandy platform delivers a trusted and distinctive natural capital navigation capability for carbon and sustainability impact management and supports farmers in managing their environmental sustainability, their profitability and their business resilience – all aligned with the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) methodology and compliant with international reporting and accounting standards

(header image provided by Bayer)

Bayer’s European Carbon Initiative enables farmers, food processors and retailers to achieve carbon commitments and implement regenerative agriculture practices.

Bayer today announced a partnership with UK-headquartered company Trinity Agtech. As part of Bayer’s efforts to drive regenerative agriculture, Trinity Agtech’s platform Sandy will be instrumental for Bayer’s Carbon Initiative in the region EMEA in measuring and monitoring carbon on a farm level. Furthermore, the cooperation will enable the customized development of Bayer’s solutions to value chain players needs and growers based on Trinity’s capabilities. Leveraging science, digital and agronomical strengths on both ends the result is a unique regenerative agriculture ecosystem, developing high quality assets for a market that needs to be committed to tangible and credible outcomes.

The European Carbon Initiative is vital to Bayer’s overall strategy to shape regenerative agriculture. This includes making agriculture more productive and resilient while restoring natural resources. Started off in 2021, the Carbon Initiative now includes multiple tailored projects with large companies from the food supply and agricultural value chain. Today, farmers across several European countries and companies across the Food and Farming supply chain are working alongside with these partners to reduce carbon emissions and sequester carbon in the soil. Project results show that growers that are using regenerative practices are emitting on average 15 percent less carbon than conventional farmers. By 2025, Bayer expects to significantly increase the number of food and ag value chain projects and the number of farmers participating in value chain programs as the European Carbon Initiative is going to switch from pilot phase to scale-up phase for commercial projects.

To support these goals, reliable monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) is key for all players of the food value chain to be compliant with third parties, global guidelines, certification bodies and regulatory requirements. With Sandy, Trinity Agtech has developed a new generation, trusted and easy-to-use cloud-based platform where farmers and project developers will bring all their data into one place to create a fact-based and primary data driven register of a farm’s natural capital. This allows the farmer to assess the farm’s carbon balance and options going forward.

“Our collaboration with Trinity offers many benefits for farmers and for our partners in the food value chain that want to deliver against their carbon reduction commitments and want to support regenerative practices in agriculture,” said Lionnel Alexandre, Carbon Business Venture Lead for Europe, Middle East and Africa at Bayer’s Crop Science Division. “We need reliable measuring technology and data analysis to verify carbon reductions and carbon sequestration on the farms. Trinity contributes with its state-of-the-art platform that is acknowledged by many experts around the globe.”

Working with internationally approved models to ensure accuracy

Trinity’s models and analytical frameworks are nationally and internationally compliant with the IPCC standards and other key global guidelines, such as the GHG-P, in addition to previous verification against ISO 14.064 and 14.067 methodologies. Trinity Agtech’s distinctive scientific board contains leading international experts to ensure the most accurate possible assessment for the farmer with the available data. A recent study commissioned by the UK Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) across 81 carbon calculators has placed Trinity’s software Sandy on the first rank in assessing farm carbon footprints and natural capital.

“We’re proud of Bayer’s commitment to credible and trusted sustainability analytics and their power in advancing the prosperity and environmental progress of the Food and Farming supply chain. Trinity is delighted to be Bayer’s analytical partner of choice in this vital program,” said Dr Hosein Khajeh-Hosseiny, Founder and Executive Chairman at Trinity.

All digital and cloud-based solutions from Bayer and its partners meet or exceed global data privacy requirements and provide data storage in the world’s most trusted cloud environments with leading security offerings. Most importantly, farmers own and control their farm data. They decide on what they share and what data they make available.

-

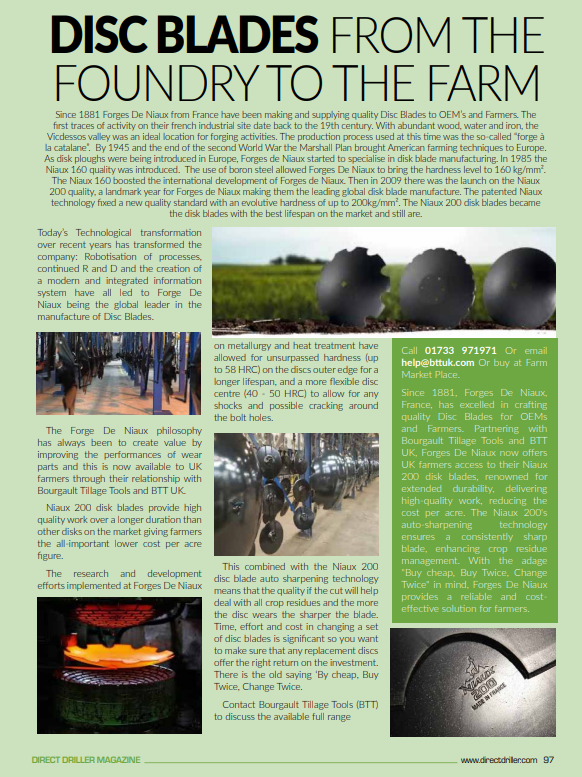

Disc Blades From the Foundry to the Farm.

Since 1881 Forges De Niaux from France have been making and supplying quality Disc Blades to OEM’s and Farmers. The first traces of activity on their french industrial site date back to the 19th century. With abundant wood, water and iron, the Vicdessos valley was an ideal location for forging activities. The production process used at this time was the so-called “forge à la catalane”. By 1945 and the end of the second World War the Marshall Plan brought American farming techniques to Europe. As disk ploughs were being introduced in Europe, Forges de Niaux started to specialise in disk blade manufacturing. In 1985 the Niaux 160 quality was introduced. The use of boron steel allowed Forges De Niaux to bring the hardness level to 160 kg/mm². The Niaux 160 boosted the international development of Forges de Niaux. Then in 2009 there was the launch on the Niaux 200 quality, a landmark year for Forges de Niaux making them the leading global disk blade manufacture. The patented Niaux technology fixed a new quality standard with an evolutive hardness of up to 200kg/mm². The Niaux 200 disk blades became the disk blades with the best lifespan on the market and still are.

Today’s Technological transformation over recent years has transformed the company: Robotisation of processes, continued R and D and the creation of a modern and integrated information system have all led to Forge De Niaux being the global leader in the manufacture of Disc Blades.

The Forge De Niaux philosophy has always been to create value by improving theperformances of wear parts and this is now available to UK farmers through their relationship with Bourgault Tillage Tools and BTT UK.

Niaux 200 disk blades provide high quality work over a longer duration than other disks on the market giving farmers the all-important lower cost per acre figure.

The research and development efforts implemented at Forges De Niaux on metallurgy and heat treatment have allowed for unsurpassed hardness (up to 58 HRC) on the discs outer edge for a longer lifespan, and a more flexible disc centre (40 – 50 HRC) to allow for any shocks and possible cracking around the bolt holes.

This combined with the Niaux 200 disc blade auto sharpening technology means that the quality if the cut will help deal with all crop residues and the more the disc wears the sharper the blade. Time, effort and cost in changing a set of disc blades is significant so you want to make sure that any replacement discs offer the right return on the investment. There is the old saying ‘By cheap, Buy Twice, Change Twice.

Contact Bourgault Tillage Tools (BTT) to discuss the available full range

Call 01733 971971 Or email help@bttuk.com Or buy at Farm Market Place.

-

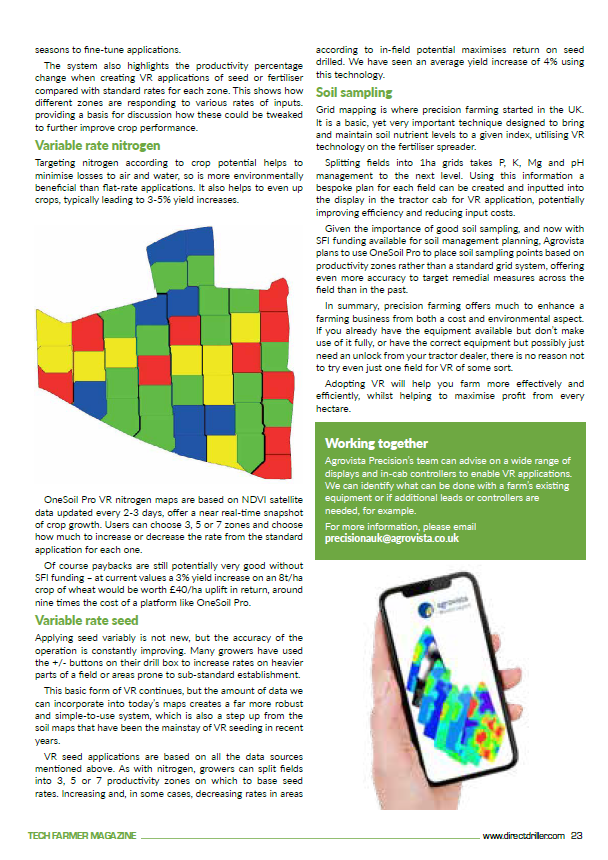

New Isobus control operation system for Novag no-till drills: efficient and powerful configurations

Written by Novag SAS. See Novag in the Drill Arena at Direct Driller at Cereals 11th & 12th June, Bygrave Woods, Newnham Farm, Herts

Novag manufactures each machine to order and allows individual configurations.

We are pleased to announce the launch of our new Isobus control system for our no-till drills. This development enables our customers to control their machines not only with our dedicated terminal but also with standard Isobus-enabled devices or the Isobus-enabled monitors of their tractors. This flexibility makes operating and integrating our machines much easier, regardless of their model.

“The introduction of the Isobus control system is part of our commitment to always offering our customers innovative solutions to adapt Novag seeding technology to their needs. They optimise their operations and increase their yield potential. We are proud to be at the forefront of the development of no-till technology and look forward to supporting our customers in this endeavour,” says Ramzi Frikha, Novag’s founder and chief engineer.

The IntelliForcePlus automatic coulter pressure control system powers all Novag models. This system hydraulically regulates the contact pressure on the coulters from 100 to 500kg.

For simultaneous metering of seed and fertiliser, all Novag no-till drills come with a two-part primary hopper. On every Novag T-ForcePlus, two additional tanks are available as an option, such as slug pellets, fine seeds, or particular micronutrients. They either deliver into the airflow of the main tanks or distribute over a wide area in front of or behind the machine. The unique software controls all four tanks, each with a hydraulic metering unit, capacitive sensors, and individual calibration.

The sowing T-SlotPlus coulters are prepared ex-factory for liquid applications (fertiliser, compost extract, enzymes, etc.).

All Novag direct seed drills are now Isobus-prepared at the customer’s request, so machine functions such as application maps for site-specific sowing can be conveniently controlled via the tractor terminal, joysticks, or Isobus VT. The Novag control systems can handle up to four product prescriptions and maps for the IntelliForcePlus closing wheel settings.

For all customers who already own a seed drill, Novag offers the option of converting the machine to Isobus control with a retrofit kit. This allows the farmer to continue to fulfil all the requirements of modern agriculture with his familiar, reliable machine.

-

A new dynamic for direct seeding

Written by Wox Agri Services. See Wox Agri Services in the Drill Arena for Direct Driller at Cereals 11th & 12th June, Bygrave Woods, Newnham Farm, Herts.

The Güttler Greenmaster Tined Seed is a completely modular direct seeding system.

Placement of the seeds takes place down an individual tube on every tine, 40 outlets on a 3.0m machine and 80 outlets on a 6.0m machine and is a European patented design.

The machine can be fitted with 410l or 660l hoppers with a choice of hydraulic or PTO fan unit.

The system allows for the attachment of the Mayor or Master trailed roller to optimise seed to soil contact, if conditions dictate then the roller can be dropped off until better conditions prevail.

To allow optimum seed to soil contact, the rollers are used in all applications of seeding.

The unit will be on show at the new Drill Arena at Cereals along with other seeding systems which we offer at Wox Agri Services.

-

Strip Tillage – A viable option for UK row crop growers who want to reduce soil movement

Written by Horizon Agriculture. See Horizon in the Drill Arena for Direct Driller at Cereals 11th & 12th June, Bygrave Woods, Newnham Farm, Herts

With over 15 years’ experience successfully applying strip-tillage practices across the world, we decided to put together a guide summarising the applications, benefits, challenges, and effects of strip-tilling. To learn more, visit the SPX Strip Till product page, or take a look at the guide directly by clicking here.

As part of our mission to design innovative products that promote soil regeneration whilst also helping our customers to improve their productivity, yield and profitability, we recognise that many farmers will require a transitional period when moving towards a no-till system. We hope to empower farmers to adopt more sustainable practices by sharing our knowledge and experience.

Below is a brief summary of strip-tillage and the benefits it has for farmers looking to transition to a no-till system from fully cultivated soils. For more specific and technical information, including detailed explanations on the effects on the soil, different applications and methods etc, make sure to check out our strip-till guide.

What is strip tillage?

Strip-tillage combines the benefits of conventional tillage with the conservation-friendly advantages of no-till farming. The low disturbance, targeted tillage approach consists of only cultivating a narrow band of soil in which the crop is to be planted, leaving lanes of uncultivated soil and residue on either side. This process reduces risks of erosion, improves soil structure and enhances soil health, and is perfect for farmers looking to transition from conventional tillage to a much more sustainable no-till approach.

Summary of Strip-Till Advantages Over Conventional Tillage

- Fuel Savings – reduced primary and secondary tillage passes.

- Fertiliser Savings – Banding fertiliser to only cover the required areas can reduce rates by 30%.

- Reduce Soil Erosion – Most of the soil remains covered with crop residue throughout the year.

- Alleviate Soil Compaction

- Weed Control – Cover crop residues can suppress weeds between the strips.

- Maintain Levels of Soil Organic Matter – Less soil movement and therefore less mineralisation occurring.

- Improved Water Retention – Fewer cultivation passes results in the soil surface between the strips being covered with crop residue.

- Yields Similar to Conventional Cultivation

- Improved Travelability in Wet Harvest Conditions

-

Come and see Moore Unidrill Ltd at Cereals 2024

Come and see the very latest Moore Unidrills at Cereals and see how far we have come in 50 years. Same name, same system, same vision – Perfecting direct drilling since 1974.

Trailed Moore Unidrill with hopper extension. – Courtesy of ST Agri – Norway distributor. Catch up on the rest of the latest News and Updates

Variable Rate Application: The Economic and Agronomic Edge for Modern Spraying

As the pressures on agriculture mount—from climate instability to rising input costs—farmers are increasingly turning…

New Standard for On-Farm Autonomy and Laser Weeding

As farms across the UK grapple with mounting labour shortages, rising input costs, and tighter…

Drones for Spraying Pesticides—Opportunities and Challenges

Erdal Ozkan; Professor and Extension State Specialist—Pesticide Application Technology; Department of Food, Agricultural and Biological…

Alternative technologies in the crop care sector

With increasing regulations and the development of resistance, alternative technologies are becoming more and more…

More Farmers Are Adopting John Deere’s See & Spray in the USA. Here’s Why…

John Deere See & Spray uses AI machine learning and computer vision to identify weeds…

Introduction – Issue 32

How full was your grain store this harvest and how have your planting plans changed…

-

Dale Drills: Crop establishment made efficient for your business

Written by Dale Drills . See Dale Drills in the Drill Arena for Direct Driller at Cereals 11th & 12th June, Bygrave Woods, Newnham Farm, Herts.

Dale Drills confirms that its range of No Till Seed Drills once again qualifies for inclusion in this funding program.

All pertinent contact details and an overview of their applicable product range can be accessed through their website, Dale Drills

Applications close 17th April 2024

Dale Drills’ range of Eco Drills presents farmers with an opportunity to efficiently establish crops while promoting healthier, more robust soils that foster higher yielding crops. But how do our drills achieve this?

The Eco Drill range employs low-disturbance tines, minimising the horsepower requirement to just 20hp/m (allowing a 150hp tractor to comfortably pull a 6m Eco M). This reduced power demand enables the use of wider working width drills (ranging from 3m to 13m) on relatively modest sized tractors, increasing output to save time and reducing fuel consumption. The lighter weight and smaller size of the tractor, coupled with the broader working width of the machine, minimise machinery pressure on the soil and decrease the compacted area, thereby ensuring optimal conditions for crop establishment.

Featuring a 12mm wide tungsten carbide tipped tine coulter, the Eco Drill offers straightforward, low-maintenance drilling in all conditions. Fabricated in Britain, these tungsten carbide tines provide exceptional durability, significantly reducing metal wear costs to approximately £1 per acre, and minimising downtime during the drilling season. The forward-facing design of the Dale point ensures an ideal seed zone, facilitating adequate seed-soil contact and preventing smearing, even in heavier or wetter soils.

The drilling assemblies, capable of independent movement, are mounted via a parallel linkage to the chassis, ensuring accurate contour following. This feature guarantees optimum seeding depth across the drill’s width, promoting uniform crop emergence and reducing the need for additional cultivation passes to level seedbeds, thereby saving time and money.

An adjustable hydraulic pressure system to the drilling units allows users to tailor the drill for various conditions, ensuring compatibility with different seedbed types, from firm direct seedbeds to looser minimum till and conventional plough-based seedbeds. This versatility ensures accurate seed placement no matter what condition the seedbed is in, optimising yield and increasing farm profitability.

Standard row width adjustment ranges from 12.5cm to 25cm (5” – 10”), with an optional 50cm (20”) kit available for users seeking the flexibility to plant crops at optimal spacing for maximum yield.

For 23 years, Dale Drills have supplied drills capable of sowing seed and fertiliser. The hoppers, painted with vehicle and machinery enamel, are effectively protected against potential corrosion from fertiliser. Specialist metering devices ensure longevity and precise fertiliser delivery. Depending on specifications, the Eco Drill can deliver fertiliser to one side, underneath, or mixed with the seed on 5”, 10”, or 20” row spacings.

Notably, the company has observed users employing multiple crop species through the Seed & Fertiliser system, either for companion cropping or sowing cover crop mixes with varying seed sizes. This inherent versatility enables users to adapt to evolving farming policies without the need for additional equipment expenditure, thereby minimizing costs.

Our Eco and MTD drill range all qualify for the FETF grant. For those considering the acquisition of one of our drills and are interested in leveraging the FETF, contact us today to explore how Dale Drills can be a strategic partner in your journey towards efficient and environmentally conscious farming.

-

Claydon – good for your pocket & good for the environment

Written by Claydon Drills . See Claydon in the Drill Arena for Direct Driller at Cereals 11th & 12th June, Bygrave Woods, Newnham Farm, Herts.

If you miss the application window for an FETF grant, you can still buy a Claydon and save £000s in your first year, just in fuel costs alone.

Hear more from Our customers – Claydon Drill Seed

Farmers using Claydon Opti-Till tell us they are saving tens of thousands of pounds every year on establishing their crops. But it’s the environment that also benefits.

Reducing insecticides

“After a year or two we started to notice important benefits and those have continued to become both more apparent and more significant. The 2019 season, for example, was the first in which we did not have to use any insecticides on wheat or spring barley as there were so many beneficial insects which took care of any pests.” A Axelsson, Sweden

Reducing fungicides

“Air infiltration is much better between the seeded rows and within the crop. This means we have been able to lower our dose of first fungicides by 50%. The farm also uses less phosphate – 30 vs 50u. With the Claydon system we are also able to inter-row hoe.”Reducing soil erosion

“It’s also about the benefits to the farm and the wider environment of protecting soils from erosion. We have some light, drought-prone land towards the coast that, under conventional tillage is prone to soil being washed away in heavy rain. With the uncultivated strips it leaves between the drilling rows, the Claydon system helps minimise this problem, while also retaining moisture in dry conditions.”Reducing soil blow

“It does an excellent job of retaining moisture and because much of the land is left uncultivated the stubble and root structures are retained, this helps to prevent soil blows which are common in Norfolk where light soils are over-worked.”Reducing chemicals

“The Claydon Straw Harrow is a key part of the system in managing stubbles between harvest and establishing the next crop. It spreads any residues remaining from the previous crop, creates a fine tilth which encourages weeds and volunteers to grow and helps to control weeds and slugs mechanically rather than with chemicals.”Improved water infiltration

“One other benefit which I am pleased to see is that our worm population has increased significantly because of the reduced soil disturbance with direct seeding. The channels which they create really help to move water from the surface and distribute it throughout the soil profile, which eliminates surface ponding.”Spring demo opportunity

Freshen up soil and remove tightness for your seeds this growing season. Contact your local dealer for a demo: https://claydondrill.com/dealers-distributors/

For more information about how Claydon drilling can help you establish your crops in a challenging climate, whilst maintaining yields and reducing costs, pls visit claydondrill.com or contact your nearest Claydon dealer.

-

The Gentle Giant: Novag T-ForcePlus 950

Article written by Novag SAS

With the new T-ForcePlus 950, Novag has succeeded in solving the conflict of objectives between high productivity, minimum ground pressure and high coulter pressure for no-till. The result is a powerful flagship that is gentle on the ground thanks to its tracked undercarriage and can also be flexibly ballasted depending on the soil type.

With up to 48 coulters (18.75cm row spacing) and working speeds of up to 12km/h, the 9m machine achieves outputs of almost 10ha/h.

New dimensions

For the new Novag T-ForcePlus 950, the frame has been reinforced and is now double foldable. This gives the 9m machine transport dimensions of 3m width and 3.95m height. When folded out, two additional wheels support the frame in the outer area and distribute the weight evenly across the entire working width. This, in combination with a new tracked undercarriage concept, ensures smooth running on the surface and precision at depth.

The seed/fertiliser tank has been enlarged, redesigned and positioned further forward than on the smaller models. This improves tractor traction and makes the tank more accessible for calibration and filling. The standard tank holds 7,700l and can be divided into 3,650l/4,050l or 5,000l/2,700l as required thanks to a flexible centre wall. Optionally, two additional tanks of 350l each are available for further seeds and granules. The additional volume can be added to the rear main tank if required.

The Novag T-ForcePlus 950 is 9.5m long and weighs 18t when empty with a row spacing of 25cm or 36 coulters. Each coulter requires an average of 10hp traction power. The smallest possible row spacing with 48 coulters is 18.75cm, so that the new Novag T-ForcePlus 950 requires a pulling force of 360hp or more.

Flexible use

For a no-till machine of these dimensions, the Novag T-ForcePlus 950 is relatively compact thanks to the intelligent frame concept. As a result, it performs very well even in prepared soils, such as those found on many farms that are still in the process of conversion. If, on the other hand, you are working consistently in a no-till system, the soil is firm and requires high coulter pressures. In this case, the Novag T-ForcePlus 950 can be ballasted up to 6,400kg if required.

New tracked undercarriage

When fully ballasted, it can reach a total weight of up to 26t with 48 coulters and a full tank. In order to distribute this load as gently as possible to the soil, the new no-till machine has been given a robust track with a very flat stud profile and a contact area of 2 x 1.3m², which does not damage the soil even during turning manoeuvres thanks to a special suspension system. The innovative suspension concept reacts flexibly to the load by changing the tension of the treads. “For European markets, we will also offer the caterpillar undercarriage with a brake system in the future,” Ramzi Frikha emphasises.

Reinforced seed metering

Despite the large working width and high working speed, the tracks and support wheels guide the seed bar evenly and smoothly over the ground. For precise seed placement, especially of heavy seeds such as beans or peas, a powerful seed metering and distribution system is required at the same time. Air flow, distribution and piping systems have been adapted accordingly. The Novag T-ForcePlus 950 has a double fan system with telescopic distributor heads that improve the seed flow.

Unique coulter system

At the heart of the new 9m model, as with all other Novag direct seed drills, is the unique Novag T-SlotPlus coulter system with IntelliForcePlus automatic coulter pressure control. It ensures precise seed placement in the soil without moving it significantly. 90% of the soil cover remains undisturbed during sowing. The specially shaped sowing coulter cuts an inverted “T” into the soil. A notched disc cuts the outcrop or stubble and opens the soil. Two separate sowing boots are located on the cutting disc to clear the seed furrow. They each have an outlet through which either seed or fertiliser can be placed at the optimum distance from each other. The T-shape of the sowing boot and the slanted press wheels guarantee an optimally closed seed slot. This means that the deposited seed is always in contact with the ground, even in dry conditions. The sowing depth can be individually adjusted from 1 to 10cm on all implements and the sowing coulters are prepared ex works for liquid applications (fertiliser, compost extract, enzymes, etc.).

Simple operation

Thanks to the high coulter pressure of up to 500kg per seed coulter, the Novag T-SlotPlus coulter system always guarantees optimum seed placement even in difficult no-till conditions with heavy biomass growth and hard soil. Likewise, the IntelliForcePlus automatic coulter pressure control always delivers top working results, even for inexperienced operators. Additionally, all Novag direct seed drills are now Isobus-prepared at the customer’s request, so that machine functions such as application maps for site-specific sowing can be conveniently controlled via the tractor terminal.

Reducing machine and labour costs

Six years of development work have gone into the Agritechnica model. “We are now also offering our 8m model, the Novag T-ForcePlus 850, on this new platform and are already working on a 10m machine, a Novag T-ForcePlus 950X. In this way, we are also giving larger arable farms access to the ecological and economic benefits of no-till. All our customers, regardless of farm size, benefit from significantly lower machinery and labour costs, whilst simultaneously saving water and improving their soil quality,” reveals Ramzi Frikha.

-

Maschio Gaspardo experience at your service!

Article written by Maschio Gaspardo

The MASCHIO GASPARDO in-line direct seed drills are the product of recognized experience and accumulated knowhow to which whole generations of both engineers and farmers have contributed over almost two centuries in the business. Today, MASCHIO GASPARDO offers a comprehensive range of direct seed drills to cater to the demands of farmers and contractors, with an array of highly adaptable products with plenty of configuration options that place seeding quality, environmental sustainability and return on investment above all else.

MASCHIO GASPARDO’S BACKGROUND IN DIRECT DRILLING

In 1989, MASCHIO GASPARDO produced DIRETTA, the first in-line seeder for drilling seed into untilled soil. Today, nearly 35 years on from that first model, MASCHIO GASPARDO continues to perfect its creations, introducing innovations that have allowed our direct drilling machines to set a benchmark for farmers and contractors.

The direct drilling range features models with mechanical or pneumatic distribution, and both fixed and folding frame versions.

MASCHIO GASPARDO SEEDING UNIT

The MASCHIO GASPARDO seeding unit, designed and manufactured entirely by GASPARDO delivers reliable, quality direct drilling, regardless of seed type and actual conditions in the field, even where there is a lot of trash material to contend with. The considerable down pressure (up to 250 kg) allows it to easily cut a seeding line even through tough soil. Seeding depth remains constant thanks to the independent furrow-opening and furrow-closing movements. MASCHIO GASPARDO direct seed drills offer an extensive range of adjustments, to better adapt to soil conditions and the farmer’s own preferences.

- Unit height spring: adjust soil cutting depths

- Clothing wheel pressure adjustment spring

- Seed press wheel arm operated independently

- Interchangeable depth gauge wheel

- Disc coulter of 475mm

- Interchangeable wear resistant cast iron shoe

- Closing wheel with soil scraper

WHY THE GIGANTE PRESSURE?

Pneumatic seed drill with pressurised hopper – The GIGANTE is MASCHIO GASPARDO’s flagship model in the direct drilling range with pneumatic seed and fertiliser distribution, available in both fixed and folding frame versions. The innovative pressurisation system optimizes distribution efficiency from the hopper to the seed furrow. With the hopper’s lowered centre of gravity, GIGANTE PRESSURE’s manoeuvrability is second to none, even when faced with steep slopes.

- Liftable seed-covering harrow

- Short distribution tubes

- External mixing head

- Hermetically sealed pressurised hopper

- Low centre of gravity

- Wide liftable wheels

- Optimal distance between rows

- Electrically driven seed + fertiliser metering units

- Steering drawbar up to +/- 90°

- ISOBUS communication

ISOBUS DIGITAL SEEDING

The metering units’ electric-drive system makes GIGANTE PRESSURE a fully digital control solution. The tractor’s ISOBUS terminal handles seed calibration and work parameter control. In addition, it allows you to access the Precision Farming.

Advanced ISOBUS monitoring functions (read+precision farming):

- TERRA 7 functions

- Prescription map import

- Geo-referenced seeding data export

- Automatic seeding shut-off

- Variable input rate

- Backlit 8″ graphic display

CENTRALIZED GREASING

A feature unique to GIGANTE PRESSURE is the centralised greasing point, conveniently located on the side of the machine, to which the rotating pins of each unit are connected.

This optional kit lets you reduce the additional time taken to perform routine maintenance on the seeding units.

-

Split Hoppers Available for 2024

Article written by Fentech Agri

Fentech Agri has been working on offering split hoppers over the complete pneumatic range of Simtech seed drills. The requirement for mixing different seeds for companion and cover cropping have become more prevalent as well as being able to offer an integrated fertiliser option for application with the seed.

Fentech agri are pleased to announce a collaboration with Regenovation, a Horizon Agriculture sister company, integrating their proven and well designed metering unit into Simtech products. The Horizon meter allows better packaging calibration and setting. Simtech mounted drills are relatively compact so this was seen as an essential requirement for running multiple meters.https://www.fentech.co/

Machines will still run a single distribution head as standard, mixing the seed down a single hose, however, the option for inter cropping on every other row is possible with dual distribution heads.

Couple the meters with another well proven and well tested control system from MC Electronics proves a reliable, simple system to accompany the reliability and simplicity of a Simtech drill.

All products will be fully supported by our technicians with engineering support from the respective suppliers should it be required.

The new combination will be integrated onto our folding rear hopper machines, splitting the 1700L hopper with a 60:40 ratio. A simple to remove baffle plate allows a single product to be used through both meters if preferred. We are also exploring the use of this arrangement onto front mounted hoppers to accompany our hopperless drill frames, giving ultimate flexibility in terms of drill configuration. With the front tank models, the option to combine a third small applicator hopper mounted to the main hopper and feeding directly into the air flow is also possible.

All new combinations will be available to order now for delivery within the 2024 FETF grant window. Contact our technical team now to discuss your seeding requirements.

-

Dale Drills – Farming Equipment and Technology Fund (FEFT) 2024

Article written by Dale Drills

In a recent update, DEFRA has disclosed the imminent opening of a new phase for the Farming Equipment and Technology Fund (FETF) grant applications. This funding initiative serves as a valuable resource for farmers looking to invest in cutting-edge equipment and technology, with the aim of enhancing productivity and promoting environmental sustainability.

Dale Drills is delighted to confirm that its range of No Till Seed Drills once again qualifies for inclusion in this funding program. In the previous cycle, numerous customers, both new and existing, successfully secured FETF grants to support their investment in a new machine from our ECO and MTD seed drill range.

For those considering the acquisition of one of our drills and are interested in leveraging the FETF, we encourage you to reach out to our sales team promptly. Given the high demand, our build schedules tend to fill up rapidly. Therefore, it is advisable for anyone intending to apply for the FETF with the intention of acquiring a Dale Drill to make initial contact as soon as possible. All pertinent contact details and an overview of our applicable product range can be accessed through our website, https://daledrills.com/.

Dale Drills remains committed to assisting farmers in optimising their operations through innovative equipment, and the FETF presents a valuable opportunity for those seeking to integrate our seed drills into their farming practices. Don’t miss the chance to enhance your productivity and contribute to a more sustainable agricultural landscape. Contact us today to explore how Dale Drills can be a strategic partner in your journey towards efficient and environmentally conscious farming.

-

Claydon Drills – Reduce your costs and improve your yields

Article written by Claydon Drills

Drilling direct and eliminating unnecessary cultivations can save you thousands in establishment costs every year, and the Claydon Opti-Till® system does just that. Compared to conventional establishment it saves approximately 60% on costs with a time saving of around 80%.

What sort of savings have Claydon customers experienced in their first year?

“Fuel is one of the big areas for saving with Opti-Till®. With the plough-based system our 15,000-litre tank had to be filled five times a season, now the tanker visits twice, which is 60% less. With fuel prices where they are that represents a major saving.” S Middleton, East Yorkshire

“In the first year that drill saved us 30,000 litres of fuel compared with our previous system . . . but there were numerous other immediate benefits in terms of timeliness, time saving, better crops and much lower costs.” T Saunders, Northants

It’s not just diesel, there are other ways to save…

“Establishing crops now needs so little power that I sold one of my two 550-gallon fuel tanks because it was no longer needed.”“One of the key benefits of OptiTill® is that it allows us to farm more land with less labour and machinery. Recently, we cut costs even more by reducing the number of tractors from three to two.”And there are no yield penalties with Claydon direct drilling

Whether farming heavy clays in Lincolnshire or dry, light erosion-prone soils of East Germany, customer experience shows that Claydon-drilled crops have no yield penalty – yields generally improve.

“Field trials have proven that the Claydon system had no detriment to establishment, providing a fantastic rooting zone required by the crop and yields were well above the pea groups set target yields.”“Half of the spring cropped area was established using the previous approach and half with the Claydon. When both were harvested the Claydon-drilled area produced 0.5t/ha more yield. The largest yield increases have been in the spring crops due to the Opti-Till® System conserving moisture at planting, especially with the dry springs that we seem to get now.”

P Wilson, Wiltshire“The drill has transformed how we farm and even after a relatively short time of using it the headlands of all our fields look as good and perform as well as the main areas, which has significantly improved average yields and grain quality.”And a little bit of science…

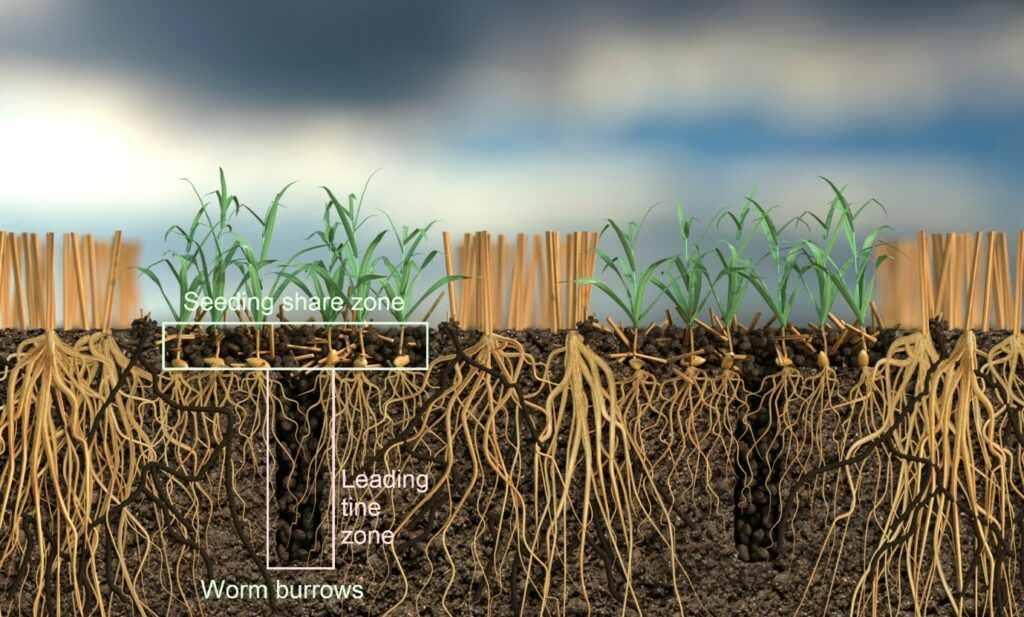

Skyway spring barley was direct drilled by 7 different drill manufacturers as part of the Agrii drill trials in Kent in 2023, comparing different drilling systems. The Claydon Evolution was the highest yielding drill with 7.46 t/ha compared to the site average of 7.06 t/ha, a substantial increased yield of 400 kg/ha over the average. The roots of the Claydon crop were the deepest and most well-developed across all the drills.

The Claydon drill’s leading tine technology is the key to maintaining, or in many cases, improving your yields. It drills direct into stubble and doesn’t turn over the soil, just aerating it in the rooting and seeding row. This means the seed gets the best start in life – friable, free draining soil and access to moisture. Meanwhile, worms thrive and process the surface organic matter, adding to the soil’s fertility. What’s not for a seed to love?

To hear more from our customers visit: https://claydondrill.com/our-customers/

Spring demo opportunity: Freshen up soil and remove tightness for your seeds this growing season. Contact your local dealer for a demo: https://claydondrill.com/dealers-distributors/

For more information about how Claydon drilling can help you establish your crops in a challenging climate, whilst maintaining yields and reducing costs, pls visit claydondrill.com or contact your nearest Claydon dealer.

-

Unleashing the Potential of Agri-Tech

Written by Chris Fellows

In the realm of agriculture, a technological revolution is underway, reshaping the landscape from traditional practices to cutting-edge innovations. This transformation, encapsulated by the term “agri-tech,” is not merely about mechanised machinery or futuristic drones; it represents a multifaceted evolution that spans the entire agricultural supply chain not just changes on farms.

Agri-tech embodies a spectrum of advancements that are revolutionising production, bolstering productivity, and addressing pressing challenges within the agricultural sector. From harnessing the power of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning to embracing biotechnology and precision technology, agri-tech is propelling agriculture into a new era of efficiency, sustainability, and resilience.

At its core, agri-tech encompasses a diverse array of innovations aimed at optimising every facet of agricultural operations. Whether it’s employing robots for labour-intensive tasks, leveraging AI to enhance animal welfare, or harnessing biotechnological solutions to bolster crop resilience and nutritional content, the impact of agri-tech reverberates throughout the agricultural landscape.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

- Biotechnology

- Precision Technology

- Smart Farming

- Vertical Farming and Indoor Agriculture

- Drones and Earth Observation Technologies

- Water Management Technologies

- Aquaculture Technologies

- Livestock Genetics and Veterinary Science

The potential of agri-tech to drive growth, sustainability, and resilience across the agricultural sector is immense. By fostering cross-sector collaboration and embracing farmers as well as farming, agri-tech innovations can unlock new opportunities for agricultural productivity, profitability, and environmental stewardship.

As we embark on this journey of technological transformation in agriculture, farmers need to stand as beacons of innovation. We need to guide the sector towards a future where agriculture is not only productive and profitable but also sustainable and resilient. Farmers and researchers need to work together, listen to each other and create solutions that really drive change not just sound good in a presentation.

-

It’s 2030 – Has food security improved?

Tom Allen-Stevens travels forward to 2030 and looks back at what progress has been made since 2024 to improve agricultural productivity.

What goes around comes around, it seems. The debate about food security and nanotechnology that we’re currently having in the first few months of 2030 has echoes of a very similar discussion that preoccupied many in the industry six years ago. What’s even more interesting is how the seeds of today’s debate were sown (quite literally) in the second issue of Tech Farmer published back in March 2024.

Cast your mind back six years to that time – swathes of the country were under water following what was then one of the wettest winters many of us had experienced, although it seems tame compared with the extremes climate change has thrown at farming since. It came on the back of the first signs of food shortages that then really came to fruition and hit the nation hard during 2025. Empty supermarket shelves started the stir of unease, and it was probably these that prompted Steve Barclay, who was then Defra Secretary of State, to suggest at the Oxford Farming Conference in January 2024 that “food security is national security”.

The call to protect our food security was one the NFU had repeatedly made to successive Conservative governments ever since the UK voted to leave the EU in 2016, as Baroness Batters to this day continues to remind the House of Lords at every opportunity she’s given. But it had fallen on deaf ears as ministers (including the hapless Liz Truss) sold out UK Farming in various bids to grasp at trade deals.

Finally, however, the message seemed to have sunk in. It was even repeated by former Prime Minister Rishi Sunak when he appeared at the NFU Conference in February 2024, and told delegates “I have your back”. Many asked then whether it was too little, too late to save an agriculture that subsequently underdelivered so seriously on the nation’s food needs during 2025. The haphazard way with which the government had thrown its £427M budget underspend on agriculture into productivity measures in the dying days of its last term in office has been the subject of too many Parliamentary Select Committees.

But there was one element of common sense that wove its way into policy at the time, and was thankfully picked up by the incoming Lib/Lab Coalition: the Agritech Delivery Fund. In particular there was the spending committed to genetics and plant breeding, that quite literally sowed the seeds of the advances we have in UK arable fields in 2030.

And that brings us back to the March 2024 edition of Tech Farmer. The issue focused on genetics, and featured on its front cover an article on the latest advances in gene-editing ready to come into the field from John Innes Centre and Rothamsted Research – the article appeared on pxx.

Surely it’s no accident that the same genetic edits found in that Cadenza wheat Professor Uauy held in his hand in 2024 are in the variety that tops, by a country mile, the AHDB Recommended List for 2030/31? An ever-increasing number of growers are now benefiting from the new premium paid by food manufacturers for the low acrylamide Group Three wheats that produce more healthy biscuits and breakfast cereals. And the world’s first commercial sward of high energy ryegrass is due to be cut this spring, with the potential to bring down methane emissions by up to 25% from the dairy cows it’s fed to.

You could argue these advances pale into insignificance compared with the LowN wheats now available to growers across the globe. Biological nitrification inhibition in wheat was largely unknown when the March 2024 edition of Tech Farmer landed (see pxx), but it’s tipped to deliver reductions in nitrate pollution alone of as much as 20% by the middle of this decade, before you even consider the productivity increases that farmers will benefit from.

Interesting too that biotech giants Wild Bioscience (pxx), CDotBio (pxx) and TraitSeq (pxx) were somewhat quaintly referred to in that issue of Tech Farmer as “agtech start-ups”. And those were the days when World FIRA (pxx) was little more than a hackathon with a few odd robots awkwardly manoeuvring around fake vineyards. Just 2500 visitors in 2024 – dwarfed by the crowds who flocked to Toulouse in Feb 2030 to see the latest jaw-dropping advances in fundamental autonomy and AI.

While these advances are awesome, the rather more sobering discussions at the 2030 event revolved around responsible use of technology. Global beef markets are still reeling from the effects of the 2029 nanotechnology scandal, that saw almost $1bn of US beef removed from supermarket shelves and incinerated. The USDA has yet to pinpoint how batches of zeranol growth hormone were contaminated with military-grade RNAi nanotechnology.

The inquiry isn’t being helped by the deep-fake videos circulating on social media that have framed everyone from Chinese terrorists to the US president herself. There is talk that this is an AI breach – a deliberate attempt by non-human intelligence to cause harm, although such a serious breach is fiercely denied by all signatories of the 2023 Bletchley Declaration.

But here in 2030, it’s raised once again the issue of food security, and at its heart is the technology garnered to increase agricultural productivity. So what do we learn from when this was last an issue six years ago?

There was much talk about food security at the 2024 NFU Conference (we didn’t have space for coverage in the March issue, but Tech Farmer did attend). Recriminations were directed at the government for failing to implement recommendations on a National Food Strategy made by Henry Dimbleby (that’s still gathering dust) while questions were asked about a Land Use Framework (that never materialised). Whether these would have staved off the National Food Crisis of 2025 remains a divisive issue.

What was interesting was the approach taken by the Foods Standards Agency on food produced from precision-bred organisms, unveiled shortly after the conference. The new regulations trod the very fine line between securing consumer confidence and enabling new genomic technologies. It set out to be “as efficient and proportionate a system” as it could be.

If 2030 agricultural productivity figures are anything to go by, the approach seems to have worked. Following Brexit, the UK dropped from the top quartile in Europe to the bottom. The most recent figures suggest the UK is back in the top quartile and the trajectory is promising. Arable crops are where the UK performs best, and that’s no surprise given the UK took the steps to ensure enabling legislation, while Europe continued to drag its heels on gene-editing.

But perhaps what shouldn’t be overlooked is the role farmer-led innovation has played in advancing crop genetics. The collaborative platform set up to do this, led by farmers and first described in March 2024 Tech Farmer (p9), now leads the world in testing novel traits – dozens of pre-commercial varieties have passed from the lab to farmers’ fields where they’ve been scrutinised and appropriate agronomy developed. It’s an open and transparent forum that generates trust in new technology. As Tom Clarke wrote in his column at the time: “when farmers collaborate they create value, and are able to capture it too” (p6).

There are considerable challenges with ensuring AI and nanotechnology can be trusted within our food system. But they have to be faced and overcome if we’re to advance as a society. The genetics revolution has shown us that proportionate regulation and the involvement of farmers bring results. So these are challenges we should be ready for.Tom Allen-Stevens farms 170ha in Oxfordshire and leads the British On-Farm Innovation Network (BOFIN).

-

Farmer Focus – Tom Clarke

Write about the future of farming, they said. We’d like your thoughts on the innovations that will help or hinder agriculture in the next 10 years. After I penned a sort of agricultural sci-fi column a few years ago in Farmers Guardian, I’ve clearly gained a reputation.

I actually farm in a fairly low tech way, on a thousand acres (400ha) of lowland peat and silt in the Cambridgeshire fens. Nearly all my machinery is second-hand, rented or has been on our farm longer than me. Yes, we use satellite imagery and GPS to make variable rate applications and seed plans. Yes, I’ve tried releasing sacks of predatory insects instead of insecticide. And yes, I now treat my farm-saved seed with endophytic bacteria which are meant to fix nitrogen from the air. But these are all practical steps driven by financial savings, or open-minded trials which tinker at the edges.

I don’t consider myself very futuristic. If you came to look around my muddy, and increasingly ramshackle farmyard, I think you might agree.

At the same time, I farm differently than my dear old Dad did. I took over from him unexpectedly 15 years ago, when he died from cancer. I hadn’t been a farmer. I was living and working in London as a management consultant. So I came to the business knowing nothing, willing to learn, open to any idea that could prove it might work.

Innovation is more a state of mind than a new gizmo. It’s finding out what works, what doesn’t, and how to do it better.

In the last decade and a half I’ve come to know a lot of farmers – and they’ve shown me there are as many different ways to innovate as there are to cook a potato. For some it’s all about the kit – the diesel heads. For some it’s the quality of the end product, or serving the customer. For increasing numbers it’s all about the soil and “biology”. But for all of us in the years ahead, it will be more and more about remaining economically viable.

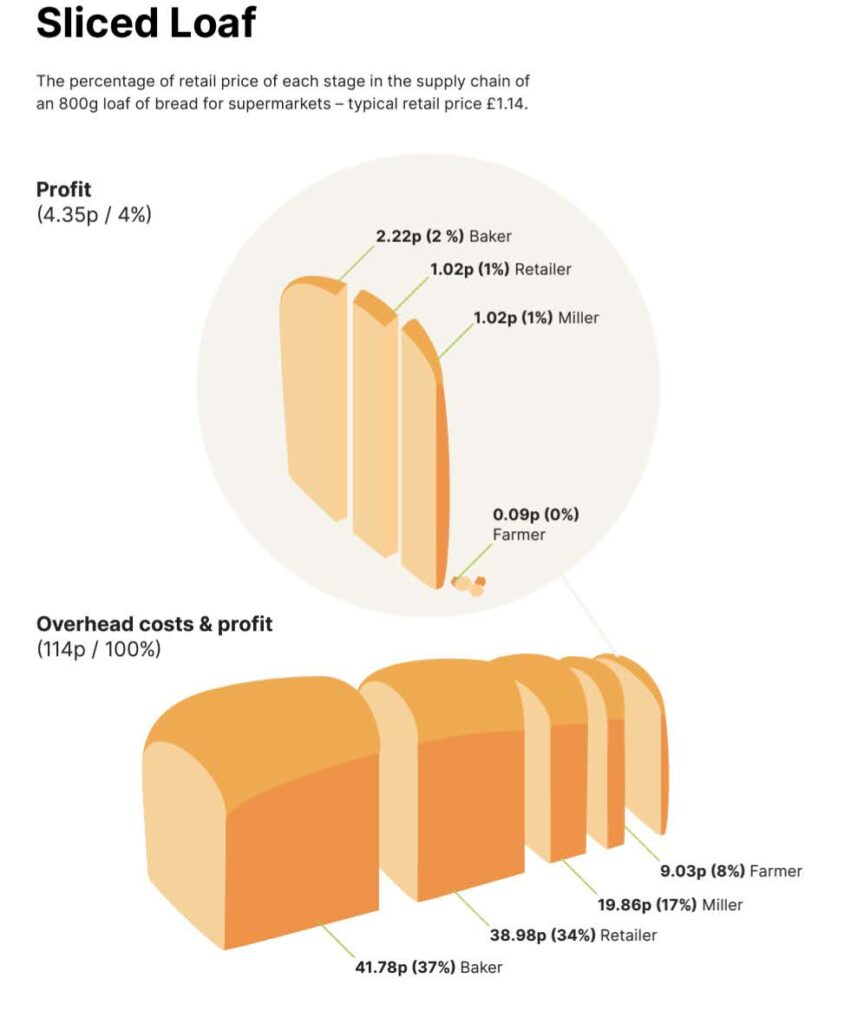

Arable farmers are in a uniquely disadvantaged economic position. There are lots of us, and we produce huge amounts of interchangeable commodity products. Because none of us produce enough to have any bargaining power, we are each price takers. When you then consider that our costs too are increasingly outside our control it’s easy to write off the whole industry as a bad job. Except, people need to eat – and the only place that comes from is agriculture. Economically, we are plankton: feeding everything, by being fed on.

Exploitation of farmers by bigger economic fish means we in turn must exploit our own resources. This is often our own labour, or the labour of our family members. It is also our natural capital – eroding what our farms can sustainably generate by maximising inputs and cultivations for short term gains.

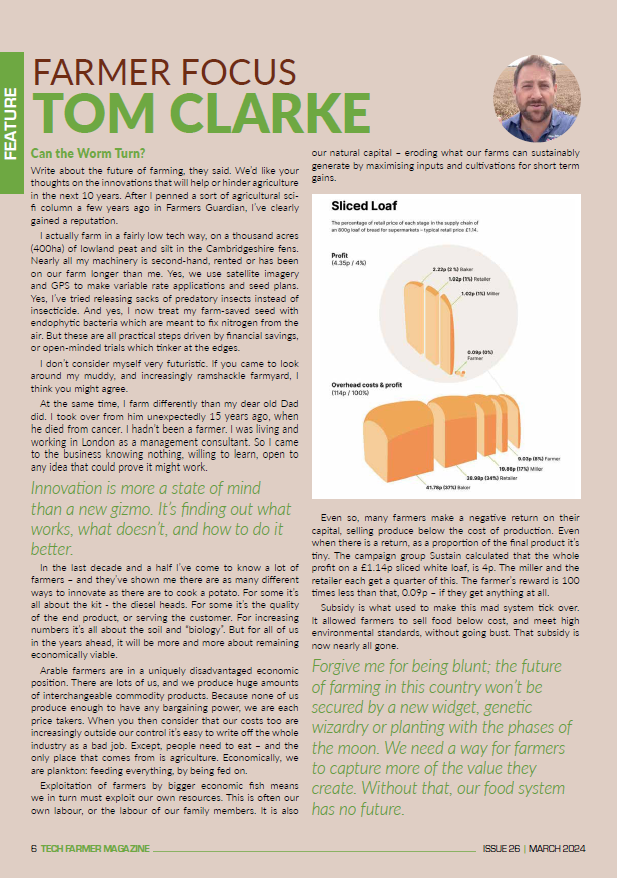

Even so, many farmers make a negative return on their capital, selling produce below the cost of production. Even when there is a return, as a proportion of the final product it’s tiny. The campaign group Sustain calculated that the whole profit on a £1.14p sliced white loaf, is 4p. The miller and the retailer each get a quarter of this. The farmer’s reward is 100 times less than that, 0.09p – if they get anything at all.

Subsidy is what used to make this mad system tick over. It allowed farmers to sell food below cost, and meet high environmental standards, without going bust. That subsidy is now nearly all gone.

Forgive me for being blunt; the future of farming in this country won’t be secured by a new widget, genetic wizardry or planting with the phases of the moon. We need a way for farmers to capture more of the value they create. Without that, our food system has no future.

I asked attendees of this year’s Oxford Farming Conference a simple poll question: “Are UK farmers in competition with each other?” – 75% of respondents said “Yes”. Well, if we are, we shouldn’t be.

Anyone reading this smugly thinking that their regen system, profitable diversifications, or multi-thousand hectare scale will see them through are still operating in a false comfort zone. Anything you can do on your own farm won’t be enough. The farm gate is no drawbridge. To influence the world beyond – where the return we make is really set – we need to change our mindsets, leave our farms and team up. We will need to create new organisations and business models that bring farmers together and pool our resources. It’s the only way we can exert any economic power. It’s also tried and tested.

Who are you paying when you buy a Limagrain seed variety? French farmers.

Any idea who owns the largest milk companies in the world? Dairy Farmers. To be precise: Kiwi, Danish, US, Dutch and Indian dairy farmers.

Do you know the name of the EU’s biggest retail bank? Credit Agricole – a French farmers’ bank. In the Netherlands too, the mighty Rabobank was started by farmers, for farmers.

In hundreds of examples from Japan to India, Brazil to Germany; when farmers collaborate they create value, and are able to capture it too. Why not here?

Already farm clusters are quietly assembling across the country; farmers who are beginning to see collaboration as the best way to access the new environmental payments.

A bigger and better beacon is the NFU Sugar Board (of which I’m an elected member). It has special legal status to negotiate the annual sugar contract on behalf of all growers. This year, we really flexed those collective muscles and, because of grower unity amid a mighty stand-off with a multinational megacorporation, were able to capture more than 25% more value from rising world markets for every sugar beet grower.

We need more collective producer organisations, ready to capture value and even take ownership of the supply chain. NFU Sugar is a one-off. Its unique position will be hard to replicate: but farmers do hard things every day.

Be in no doubt, the big fish won’t hand over value easily. The recent bust up over the Greener Farms Commitment shows the widely-held expectation that farmers are supposed to just hand it all over, and be grateful for the business.

What supply chains really need now is our data; information only we can provide about our environmental footprints. We have become so used to passing up the value of our produce, I fear too many of us think we have to hand over this new value from our data too. But this is an opportunity to draw a line in the soil. Data is a lot easier to pool than wheat, cattle, or even sugar contracts, and collectively we have a monopoly on it. Can the worm turn?

With political, market and climate instability rising around the world, farmers everywhere are protesting. Most of these demos are asking for more from governments. A few are forming political parties, perhaps to become part of governments, or to wreck them. I say, the solution to economic problems is economic action.

-

The power of diversity

A change in English law now allows certain gene-edited crops to be grown on commercial farms. Tech Farmer visits the scientists working with a new farmer-led platform that will make the first three introductions.

Rarely would you find so many misfits in the same place. Looking closely you can see spikelets within a wheat ear that seem to have spawned sub-spikelets. Misshapen ears. Short and stubby. Long ears with seemingly impossibly lengthy grains.

They seem unnatural, but they’re not, explains Professor Cristobal Uauy, group leader in wheat research at the John Innes Centre, Norwich. “This is natural variation that’s already out there in the fields. What we’re doing is trying to combine genetics and genomics with the biology of the plant – understand the genes that govern yield.”

That’s why the weird wheats are intensively wonderful to Cristobal and his team. They’re a route to understanding the genes and promoters of the MADS-box transcription factors they’re studying. These are associated with genes that govern diverse developmental processes, such as meristem specification, flowering transition, seed, root and flower development, and grain ripening.

“Yield is very complicated, just like intelligence in humans – many genes affect it,” explains Cristobal. “So we’re trying to break it down into these smaller components – what makes the grain heavier or longer or wider.”

There’s one wheat in particular we’ve come to see, and Cristobal alights on a collection of potted plants, puts one on the floor and bends its ear so that the glumes separate in an arch. You’re struck by the size of the florets. “This is Fielder, a spring wheat that scientists study a lot, so we know its genome. We’ve edited this at a very precise point so it produces these larger grains.”

The grains are in fact around 5% bigger than the unedited original, they have a higher thousand grain weight (TGW) and specific weight. So does that translate into a higher yield? “There’s a consistently higher specific weight, which is exciting for millers, but so far we haven’t seen a major yield effect,” notes Cristobal.

Wheats with unusual characteristics suggest they are a source of genetic diversity, so are closely studied. “The next step is to see how it works in the field. And that’s a critical step, because a plant can perform one way in a pot, but very differently in a farmer’s field. We need to know how these novel crops will behave under a commercial cropping regime, and whether its unique aspects can be enhanced through agronomy.”

This work is now set to get underway, thanks to a new farmer-led platform set up by the British On-Farm Innovation Network (BOFIN), working with industry partners (see panel on pxx). The plan is that this Fielder wheat will be one of the first three gene-edited cereals to be grown in commercial fields by farmers. “We have less than 1kg of seed at the moment, but we will multiply up enough for agronomic field trials and then for commercial crops, planned to go in the ground in spring 2026.”

Bigger, bolder grain

The discovery of this bigger, bolder grain happened over 250 years ago. “It was originally characterised in 1762 by botanist Carl Linnaeus, who documented the long grains, glumes and lemmas of a Polish wheat, Triticum polonicum. But exactly what gene controlled this has remained a mystery,” notes Cristobal.

Pivotal work was carried out by James Simmonds at John Innes Centre, who managed to create a stable cross of the wheat with Paragon. “We thought we had a pretty good idea of the gene responsible, but it wasn’t until the wheat genome was published in 2018 that we knew for sure.”

The edited Fielder wheat has notably larger glumes. Cristobal explains that wheat, a hexaploid, has three copies of its genome, making it one of the most complex of all organisms with around 16 billion letters. An international collaboration resulted in a map of the wheat genome and has accelerated understanding and the roles of specific genes.

“We’ve identified the gene responsible as VRT-A2 (Vegetative to Reproductive Transition). The genes that govern glume development are the same in all wheats, but the sequence that regulates it are different.”

What the team discovered was that VRT-A2 has the effect of “putting the brake” on glume development at a particular point in the plant’s growth. There’s a misexpression of this gene in the Polish wheat so that glume development continues unabated. Using CRISPR, the team has now replicated this effect with a sequence rearrangement in the DNA of VRT-2A, bringing the bigger, bolder grains to Fielder.

“What we want to understand now is how this VRT-A2 expression is controlled by the edit we’ve made. There are downstream genes that will be affected and we want to identify these and look to see how agronomy can influence the resulting traits.”

Nor is VRT-A2 the only gene in the MADS-box the team is studying. An international collaboration including JIC has identified SVP-A1 (Short Vegetative Phase) that has a similar effect. “The gene also appears to have an influence on glume length, so again it’s not until we bring this out into the field that we can look at how to manipulate it.”

Another promising route is GW2, a gene that regulates grain width. The team generated mutant wheat lines where the effect had been knocked out of autumn-sown variety Cadenza through TILLING (see panel later on).

The next step is to see how the wheat works in the field – critical, because a plant can perform very differently to how it does in the lab. “We generated mutants that had the change on just one of the wheat’s three genomes, on two and also on all three. Here we achieved an increase in TGW of 6%, 12% and 21% respectively. However, again we have seen no increase in yield, and what’s more, it resulted in lower tiller numbers. But an interesting aspect is that protein content was higher – you’d expect a dilution effect, but this didn’t occur.”

Work is now underway to edit the GW2 gene in Skyfall, with a true PBO expected in about 18 months. “We have colleagues at JIC who are developing other wheat PBOs, for example with high iron or zinc content in the grain. There is also robust yellow rust resistance coming through,” notes Cristobal.

The plan is to put all of these traits through the farmer-led platform as enough PBO material comes available. “It’s fascinating for us as scientists realising what can be achieved with new genomic technologies. We want farmers to see this for themselves in their own fields and bring about a revolution in how we grow wheat. We think the improvements we can now bring forward in plants will not just help the environment, but bring greater food security for all people around the world.”

Applying PROBITY to new genomic techniques

A Platform to Rate Organisms Bred for Improved Traits and Yield (PROBITY) is a new industry-wide initiative led by BOFIN. It brings scientists, plant breeders and food processors together with farmers and agronomy research specialists to explore gene-edited crops.

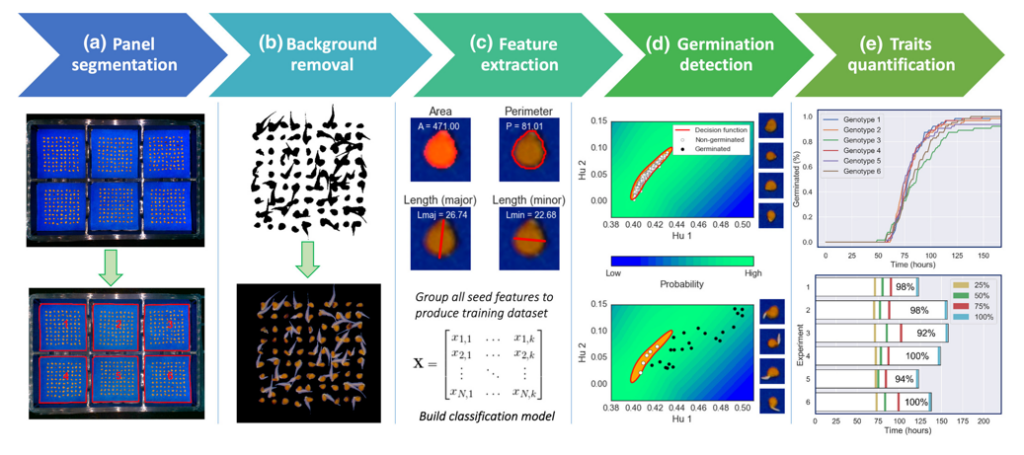

The platform has been made possible by new legislation that allows precision-bred organisms (PBOs) to be grown on commercial farms in England (see panel on pxx). PROBITY aims to explore the attributes of novel crops in a transparent and open forum. Up to 25 English farmers will carry out on-farm trials and produce enough material for batch-processing or feeding trials of the first three PBOs, which are already in multiplication plots at UK research institutes.

English farmers will carry out on-farm trials and produce enough material for batch-processing or feeding trials of the first three PBOs. These will feed through into agronomy trials and breeder plots in the 2024/25 cropping year, with the first crops grown on commercial farms the year after. Around 12 novel traits have already been identified and are expected to follow into the platform, creating a pipeline of new breeding technology.

The platform is designed to complement the existing route to market for conventionally bred crops, says BOFIN. PROBITY specifically aims to address traits where the value and market attraction may currently be unclear, as well as a testbed to import or export novel traits.

Importantly, BOFIN says the varieties multiplied up will be non-commercial, with the emphasis being to test a novel trait and give breeders the confidence to bring these into the latest varieties. For more information, email info@bofin.org.uk.

Jargon-buster: what does it all mean?

Mutagenesis is a change or edit in the plant genome that confers a new trait. Such mutations occur naturally every day, when a plant comes under stress, for example, or it can be induced through human intervention. A small change in the genome may switch off the activity of a particular gene which allows or inhibits a property, and it’s these phenotypical changes breeders have sought out for generations to progress their lines.

Mutagenesis differs from Transgenesis, where DNA from another species has successfully been combined into the genome of the host plant. These are universally classified as Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs). In the UK and across the EU, the release and cultivation of GMOs is highly restricted, although they are allowed in imported food and feed for livestock from parts of the world, such as the Americas, where they are widely grown.

Cisgenesis is where DNA is artificially transferred between organisms of the same species, such as from a wild relative to an elite potato variety to confer blight resistance. In Europe at least this is still classified as GM as nucleic acid sequences must be isolated and introduced using the same technologies that are used to produce transgenic organisms.

For decades, scientists have induced mutagenesis to bring about new traits, or phenotypical variations, using chemicals or radiation. TILLING (Targeting Induced Local Lesions in Genomes) is a powerful reverse genetics method used in plant sciences which allows the identification of point mutations, introduced randomly throughout the whole genome by chemical mutagenesis.

In the UK and across the EU, the release and cultivation of GMOs is highly restricted. More recently, more precise gene-editing techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9 have been introduced. CRISPRs are short RNA sequences introduced into the host plant that recognise a specific stretch of genetic code. Cas9 enzymes partner these sequences and cut the host DNA at specific locations.

The cell tries to repair the damage, and that’s when the mutation occurs. By using different enzymes and techniques, researchers can deactivate or alter – edit – specific parts of the genome, thereby conferring traits.

Legislation around New Genomic Techniques (NGTs), such as CRISPR, is changing. In England, the Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Bill was enacted in 2023. This allows the release and marketing of precision-bred plants, which had previously been restricted by European legislation governing GMOs.

It affects cases where NGTs have been used to edit a plant genome to bring about traits that, according to scientists, could have happened naturally. Where this is the case, these plants are now treated as Precision-Bred Organisms (PBOs) – effectively the same as conventionally bred.

The legal change applies in England only – devolved governments have yet to follow suit – and while similar legislation on NGTs has recently passed through the European Parliament, it’s yet to be adopted in EU member states.

Supply chain benefits from novel crops

Biscuits and breakfast cereals from the first gene-edited wheats grown on commercial farms in England are the plan as part of the new BOFIN farmer-led platform set to put the novel genetic technology to the test.