If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Drilling for Success: The Versatility of AMAZONE’s Tine Drills

In the current farming climate, growers require drills with maximum flexibility to handle multiple crop types and establishment methods. AMAZONE has developed a range of tine drills to meet these challenges. Since the late 1970s, the company has utilised the TineTeC coulter across various models, more recently including the Cayena, Condor, and Primera DMC. The slim chisel opener provides excellent penetration for precise depth control, even at shallow sowing depths, while minimising soil disturbance to reduce moisture loss and limit weed germination.

For farmers like William Forsyth, who works with heavy clay soils

across his 2,200 ha Warwickshire farm, this adaptability was essential. His previous disc coulter drills lacked the necessary pressure to maintain consistent seed depth, leading him to invest in three Condor 12001-C drills.

Cayena TineTec coulter

Condor ConTeC pro coulter After first trialling a Condor in autumn 2023, William and his father Anthony were immediately impressed with the drill’s versatility. Despite the wet and steep conditions on the demo day, they successfully used it for direct drilling, as well as into tilled and ploughed ground.

“The seed was at a completely even depth across the entire machine, something we were not used to at all with our previous drill,” stated William. “Setting the seeding depth is also surprisingly easy, with a tool on each end of the drill to adjust the depth of individual coulters, making it simple to get the right seed depth behind the tractor wheels.”

Condor 12001-C

Cayena 6001-C The chisel action of the tine forms a clean seed slot, placing the seed without seed/straw contact. This improves germination and eliminates the risk of residue breakdown affecting crop establishment. The long coulter spacing allows row spacing to be as narrow as 16.6 cm while ensuring that surface residues pass through the drill without blockages. The Cayena model further improves residue management with a row of vertical front cutting discs that slice through trash ahead of the coulters.

William also noted the reduced pulling power of the new Condor drills, allowing the tractors to run at lower revs, reducing fuel consumption. Additionally, the fast folding and unfolding process makes field-to-field transitions effortless—a key factor when working with a 12-metre drill on fields averaging just 9 hectares.

The MultiBin System: Precision and Efficiency

With these models of tine drills having the ability to establish a cover crop straight into stubble – or into a stale seedbed, sow a cash crop following last year’s cash crop or to sow a cash crop into a cover crop, the AMAZONE tine drills are equipped with the MultiBin system with a divided hopper along with additional seeder boxes. Using the divided main tank, available with either two or three chambers, the drill can be used to sow a multitude of seed varieties as well as undersowing crops, companion crop planting, or mix of seed and fertiliser to target phosphate in the seeding zone. Additionally, the MultiBin system can be used for a mix of seed and slug pellets, or seed and a micro-granular herbicide. Each hopper within the MultiBin system is controlled via ISOBUS individually and can run off three or four variable rate application maps for site-specific, part area application where seed populations are matched with soil type and topography to maintain an even crop density.

As farms incorporate more diverse crop rotations, changing seed types or mixes has become more frequent, meaning seed calibration has become a much more regular task. TwinTerminal involves a secondary terminal mounted on the drill near the metering units, allowing for easy calibration and pre-metering for all seed hoppers and metering units without having to jump in and out of the cab. Simply hold the calibration button and then enter the weight of the metered seed Simply hold the calibration button and enter the weight of the metered seed. William’s team described how it saved them significant time and reduced the need to jump in and out of the cab.

Optimised Reconsolidation for Strong Establishment

Beyond precision seeding, AMAZONE’s tine drills ensure robust crop establishment through their unique reconsolidation system. Strip-wise reconsolidation, where only the seed row is firmed while the area between rows remains loose, is key to improved water infiltration and reduced weed germination.

With conventional drills, capped soil surfaces and poor drainage often hinder establishment. However, the Condor’s depth and consolidation rollers ensure uniform firmness around the seed, maintaining moisture availability even in dry conditions, whilst leaving the areas between the coulters undisturbed. Similarly, the Cayena drill uses a Matrix profile tyre, which applies pressure precisely in line with the seed rows, mirroring the spacing of the tine coulters.

Strip-wise reconsolidation with the Matrix tyre profile. Cost-Effective and User-Friendly Design

The ability to direct drill, work in a min-till system, or function as a conventional

seeder means farmers like William get maximum flexibility from their drill investment. Setup is straightforward, and with fewer moving parts, wearing costs are kept low—something every farm operation can appreciate.

Available in working widths from 6 m to 15 m, AMAZONE’s tine drills offer efficiency without compromising precision. With lower fuel requirements, adaptable seeding options, and user-friendly operation, they are an ideal investment for modern arable farming, delivering reliable performance across a variety of soil and establishment conditions.

-

Foliars mean less nitrogen with increased yield and protein

Rosalind Platt is managing director of crop nutrition specialists BFS Fertiliser Services Limited.

Foliar nitrogen treatments later in the season reduce the total amount of nitrogen needed while maintaining or lifting yield, and increasing protein.

The pressure on farmers today seems more relentless than ever. Key priorities are to maximise soil health and nitrogen use efficiency while maintaining yields, as well as increasing protein levels in milling wheat. As a UK leader in crop nutrition for more than 75 years, BFS has developed fertiliser programmes tailored to meet these challenges.

One solution is our foliar nitrogen product, PolyNPlus Foliars; another – our protein enhancers, Profol and ProfiPlus – gives farmers flexible options to increase protein in milling wheat.

Over many years, independent research on PolyNPlus by one of Britain’s oldest agricultural research centres, NIAB, and international farm managers and agronomists, Velcourt, has verified the excellent results achieved by farmers.

Nitrogen, vital to maximise yields in crop production, is traditionally soil-applied as ammonium nitrate, urea or liquid UAN. Farmers would normally make two or three applications of soil-applied fertiliser in the spring. But later in the season the nitrogen use efficiency of these types of fertiliser, whether solid or liquid, can decline to 25 to 30%, especially when the conditions are dry – see charts.

When the leaf canopy is sufficient, PolyNPlus Foliars can replace a proportion of the soil-applied nitrogen for a wide range of crops including cereals, oilseed rape, sugar beet, potatoes and maize. Application timings combine well with fungicide.

Application rates vary by crop. As a guide, and depending on soil and weather factors, 25 litres of PolyNPlus – supplying just 8kg of nitrogen – can replace 40 to 50kg of any type of soil-applied nitrogen. This can cut the carbon footprint of the third application by 77 per cent – PolyNPlus’s sticky nature prevents nitrate loss, avoiding groundwater contamination, and the loss of ammonia is minimal.

Therefore farmers can apply less nitrogen while maintaining or increasing yields.

Paul Jannaway, a Wiltshire-based contractor working with several large landowners, said: ‘The yields and quality of the products we harvested were excellent. I applied PolyNPlus in all conditions, even when it was very hot, and had absolutely no scorch. I believe we will see a lot more of this product – PolyNPlus is the future.’ As well as using PolyNPlus successfully on wheat and rape, he has used it on oats just before the panicles or oat heads emerged, and recorded a bumper crop.

PolyNPlus is the only foliar nitrogen which has been extensively and independently trialled.

Protein enhancement

To increase protein later in the season for milling wheat showing potential, applying additional nitrogen at growth stages 69 to 75 is highly effective. BFS’s urea-based solutions boost protein and improve the prospect of premium prices.

BFS Profol (18N) is a urea solution and, as a foliar application, has a rapid uptake even in dry weather. It is used at 200 litres per hectare to provide 40kgs of nitrogen per hectare.

If a smaller quantity or reduced application rates are preferred, we supply ProfiPlus, for which the timing of application is more flexible, in 10 hectare packs. It is a hybrid product which includes a small amount of PolyNPlus, sulphur, magnesium and seaweed extract. These ensure rapid uptake and slower release of nitrogen, meaning ProfiPlus can be applied earlier than Profol, and making it more efficient than other solutions.

A foliar future

Foliar nitrogen is set to play an essential role in the future of farming. It is a cost-effective way of improving nitrogen use efficiency, maintaining or increasing yield and protein, reducing pollution and cutting a farm’s carbon footprint.

-

Farmer Focus – Ben Taylor-Davies

Embracing Diversity and Branding for Farm Resilience

Up horn, down corn – never has this statement been so true and never have the principles of regen ag been so ultimately important for profitability and the ironing out of the horrific bumps in the road ahead. 2024 saw us have almost double our annual rainfall average (measured since 1930) of 1130mm, that combined with the lack of light intensity and depressed combinable crop prices are a recipe for disaster when compared to just 2 years ago when everything looked so different for high input, high yield farming.

On 18th November 2020 we purchased 10 Hereford cross heifer calves and bucket reared them for the long term, these were going to be our suckler herd of the future, the following year we added 20 Angus heifer calves for the same purpose. I was once told that you bought chickens to lay and sell eggs every day, pigs every 4 months, sheep every 6 months and cows every 24 months. Spreading risk and income streams was the mission we were on after having all of the previous on the farm already. In hindsight we should have begun with the cattle and finished with the chickens to get ahead of the game, but we find out generally after the event.

Cows and calving, purchasing a bull etc has gone well and have realised the size of the herd explodes in size when you’re into the 3rd year of cows calving, we seem to have over stretched the size of barns and the amount of herbal leys we have on the rotation and therefore about to sell 41 head, just the simple task of a TB test to clear first! The beef market is at all-time highs and as the time comes nearer, the nerves that the market will ‘hold’ become ever more real! If all goes according to plan, the cattle and lambs this year will bail out what looks like the doom of the arable side of the business, much like the vineyard did in 2022 when everything pretty much the crops died of drought stress.

Diversity is still the main driving force of the farm and I find it odd that when you talk to so many about diversity the response is we shouldn’t need to, blaming supermarkets and the like. I see things slightly differently and not sure blame needs to be apportioned, but equally the easiest action to take. The whole world works around profit, the easiest way to produce profit is to become desirable in what you have to sell, which often leads to the formation of a ‘brand’ in essence a brand is profit, it differentiates you from competitors and makes it almost impossible to make accurate comparisons between goods and services. As farmers of course, everything ‘bought’ onto farm is a ‘brand’ ag chem companies get a good kicking, but rarely if ever do I hear the same rhetoric when discussing say banks, and their profits are enormous, but have you ever tried to compare their services? interest rates are one thing, but ‘hidden’ charges are just about everywhere and at different values.

Why is this important? Well, we essentially buy in brands, to generally produce a commodity (of which has zero branding) and total price takers, only for the first thing to happen to the commodity we sell to be turned into a brand as soon as humanly possible! A chicken, plucked, wrapped and put on a shelf is easily comparable and therefore profitability is much lower to say taking that chicken, dicing it up, shaping into a dinosaur and covering it with breadcrumbs, the value of the chicken has trebled in this process.

We have recently worked out that, not only do we need to take far more control of the ‘brands’ entering the farm but need to try and brand things leaving the farm. Wildfarmed wheat is a great start, but so much more can be done and the development of our ‘Added value alley’ where are producing ancient grain pasta, biltong, air dried meats and fruit biltong is showing the profit is in branding and not in chasing yield. I’m not sure any of this is that much different to what my great grandfather was doing, lots of diversity of income streams, selling local, by reputation of what he produced (branding). It was this generation that often tenants made enough from their produce to purchase their own farm, perhaps we need to look backwards in order to move forwards and realise that diversity is something we should all embrace whenever we seek profit and take ownership of your brand, it could and should build confidence and ultimately see a farms long term sustainability.

-

Agronomist in Focus – Cameron Ferguson

Responding to the challenges of climate change and extreme weather with versatile varieties

Although it’s fair to say that growing cereal crops in the western half of Scotland has always been a challenge with unpredictable weather and a shorter growing season, it’s now apparent that “tough” is becoming “very tough” following two out of the last three autumns’ where its been virtually impossible for many farmers to establish a winter wheat crop.

Born and bred in Ayrshire, I’ve worked for the last 5 and a half years for Agri-Source, a division of L S Smellie and Sons limited (pronounced “Smiley” by the way) so I’ve seen the landscape of farming in western Scotland change significantly over the last 40 years, and, in many ways, not for the better.

Farmers in my patch covering Ayrshire, Renfrewshire and some of the outer lying Islands within the county of Argyll, have always been incredibly resilient. But waiting for a drilling window that doesn’t come after you’ve pre-committed to major input purchases such as fertiliser and seed would test anyone’s patience.

As a boy, some of my happiest memories are of tobogganing in deep snow or ice skating on the local river Ayr. There were always four distinct seasons back then, and farmers knew and trusted the calendar to plan ahead of each new season. As of 2025, I can’t tell you the last time we had sufficient snowfall to justify getting a sledge out of the shed or the last time any local rivers where frozen over enough to skate on!

What I do know is that autumn, winter and often early spring have now become one mild, extremely wet, six month period where key establishment decisions are either not being made or, at best, being made during a rare good weather window making it increasingly difficult for agronomists and distribution, particularly the bigger agrochemical distributors, to react quickly enough. Fifteen years ago, all my customers ordered spring seed before Christmas. Now they’ll often leave purchasing decisions till as late as mid-March. Again, all down to the unpredictability of climate change.

For balance, can I also mention that, whilst I firmly believe we are living through a period of climate change, I am more sceptical about the source of temperature rises. Whilst there’s an argument for man-made contributions to rising global temperatures, we have to remember that the earth has been much hotter than it is now and that during that warmer period, before the last ice age, human beings weren’t industrialised or polluting the world with greenhouse gases. What is happening right now is the latest chapter in a world warming cycle that we’ve been living through for 10,000 years since the end of the last ice age. Scientists will argue about the speed of recent change, but, in my opinion, it’s difficult to form a definitive opinion in the face of conflicting science.

So, what’s to be done to help growers in my region, and many others in the UK, facing similar climatic challenges?

As an agronomist, the answer for me has to be science based. Specifically in plant breeding technology, focusing on improving genetic traits such as rapid early growth, earlier maturity and perhaps, most importantly, drilling flexibility rather than always prioritising yield and disease resistance.

When I look at the current AHDB lists, one variety – Blackstone, a Group 4 soft wheat, from breeder Elsoms Seeds stands out from the pack. I first saw the variety in National List year 2 trials in 2023. At first glance, it was taller than most and, in comparison to other plots, it looked relatively clean showing fewer signs of either rust or septoria – a good early positive.

However, when I saw the 6 month recommended drilling window for Blackstone, September 1st to the end of February, and then explored the varieties’ vernalisation data in more detail showing evidence of high to full levels of vernalisation for plots drilled in late March, I began to form an idea that this variety could be an answer for many growers caught in a difficult scenario of deciding if they should risk drilling a winter wheat in spring.

With another long, wet autumn and winter on the horizon for 2023/ 2024 I didn’t have to wait long to test my theory and I remember sitting down with farmer Jamie Kyle, a successful mixed farmer from the Robstone Farming Company, near Stranraer to talk through his spring rotation and the inherent risk involved in growing a winter wheat as a spring wheat.

Whilst I’ve no doubt many agronomists would rightly question my decision given the AHDB official advice and the breeder’s own recommendations, I would like to add that spring seed was very scare in spring 2024, we had the Blackstone seed on farm by late April, it was paid for, plus we’d assessed the vernalisation data supporting the case for Blackstone up to a potential late March drilling slot. The only question remaining in my mind was could Blackstone perform as well, if not better, than bonified spring wheats such as Talisker if drilled in April?

Drilling 10ha of Blackstone at a high seed rate of 400 seeds per m2 on April 28th following a late harvested crop of potatoes the crop got away well, racing through its early growth stages and competing well against the main weed burden of annual meadow grass. On nutrition, 2 main splits of Nitrogen were applied totalling 160kg/ha, and, on fungicides, we went with just a 2 spray program. Spring is a relatively short season in west Scotland, so any septoria present was coming into a growing crop, not waiting to explode since the winter so I believed a 2 spray strategy was justifiable.

Applying the T1 spray on June 12th, we went with 1l/ha of bixafen + prothioconazole + spiroxamine alongside 1l/ha of folpet. This was applied one week after Blackstone had received its second split of Nitrogen and, I have to say, it had tillered well and was looking exceptionally lush. To give it an extra boost we applied 3l/ha of Seamac Gold foliar feed, and, on July 16th, we applied the main T2 ear-spray using the same T1 chemistry but adjusting the dose rates to 1.2l/ha on the bixafen + prothioconazole.

Blackstone stood very well showing no signs of lodging but, despite its height and although it looked quite forward, I felt there was no requirement for a plant growth regulator.

Harvesting on October 3rd, Blackstone combined well achieving a final overall yield of 7.4t/ha at 15% moisture, as good a yield as any spring wheat I’ve grown and a remarkable performance for a winter wheat sown almost 2 months outside its officially recommended drilling window. Jamie Kyle was delighted and will be increasing his area of Blackstone to 16ha for crop25 with a firm eye on the distilling market again with Grant’s distillery on his doorstep.

There’s definitely a need for more varieties with Blackstone’s drilling flexibility and well done to breeder Elsoms Seeds for stepping up with their Responsive Rotations initiative to try to address some of the ever-growing pressures faced in modern day farming. Blackstone is certainly a step in the right direction.

-

Unlocking the power of genomics: What it means for farmers

Biostimulants are becoming a staple in agriculture, enabling growers to boost crop health, resilience, and yields in a cost-effective way. Until now, farmers and agronomists have assessed the efficacy of these products through phenotypic observations – measuring visible changes such as larger root systems, greener leaves, or improved overall plant vigour. While this approach has served the industry well, genomics is now enabling a deeper, more precise understanding of how and why these changes occur.

What is plant genomics?

Plant genomics is the field that explores the complete genetic blueprint of plants, including their DNA structure, function, evolution, and interactions, with the aim of gaining insights into plant biology and enhancing crop performance.

The benefits of biostimulants are generally evaluated based on physical changes observed in the field. For example, data from the University of Nottingham has shown how certain biostimulants lead to enhanced root growth and greener leaves. However, this only tells part of the story. With genomics, it’s possible to go beyond surface-level observations and identify the genotypic responses driving these visible improvements.

“Genomics is not about altering the plant’s DNA, it’s about understanding genetic pathways and behaviour, i.e. ‘reading the book without altering the words,’” explains John Haywood, at Unium Bioscience. “It’s our aim to understand the link between plant biology, genetics, nutrition, and biostimulants, to create solutions for growers, allowing us to build a deep understanding of the mode of action of our products,” he says.

John Haywood explains that this targeted approach enables the creation of more reliable and lower-cost solutions for farmers. He highlights that 60-70% of crop production is lost to abiotic stress (environmental stress) compared to just 20% lost to biotic stress (pests, diseases, and weeds). “However, only around 40% of farmers are using biostimulants and biologicals to mitigate biotic stress. With genomics, farmers have the power to use reliable science to create future solutions, addressing both biotic and abiotic stress more effectively.”

Understanding plant stress at a genetic level

Genomics provide valuable insights into how crops respond to abiotic and biotic stresses. Whether plants are facing drought, heat, cold, or disease pressure, genomic analysis reveals which genes are being upregulated or downregulated -essentially showing how the plant is reacting on a molecular level.

Layne Ellen Harris PhD, owner and research consultant at Foresight Agronomics, specialises in plant gene expression in response to biological agricultural products., and emphasises that gene expression is the key to understanding what is happening beneath the surface of the plant. In the past, the industry has observed that “biostimulant plus application equals expected results,” but the reason why it happens remained a mystery. Genomics answers this by revealing the central dogma of molecular biology – the process of information transfer in cells from DNA to RNA to protein. By identifying which genes are being expressed in response to stress or biostimulant application, scientists can see how plants adjust their biological pathways.

“For example, drought stress triggers biochemical and genetic pathways within the plant to develop coping strategies such as being more efficient with the way it uses water. If we can use products that trick the plant to elicit the same responses, making it think it’s stressed, but making it be more resistant to stress down the road, that’s going to have huge benefits to farmers,” she says.

Benefits to farmers

The greatest advantage of using genomics in biostimulant development is the increased likelihood of seeing a strong return on investment (ROI). With a clearer understanding of how products work at the genetic level, farmers can be more confident that applications will deliver consistent and measurable results.

Tim Eyrich, head of agronomy and innovation at HELM Agro, has over 41 years of expertise in agronomy and horticulture and points out that studying genomics at the field level reveals the interconnectedness of biostimulants and crop nutrition. “Biostimulants rely on optimal nutrition to be effective. By understanding this relationship, farmers can ensure that nutrient dependencies are addressed before applying biostimulants. This enhances both product performance and ROI.”

He also highlights the Importance of timing, explaining that in trials with the biostimulant, Scyon, applying it as early as possible (at the three-leaf stage in wheat) allowed plants to develop better coping strategies for abiotic stress, resulting in improved phenotypic characteristics.

Additionally, genomics helps biologicals specialists like Unium Bioscience accelerate the development and positioning of new products, bringing effective solutions to market faster and at a lower cost – savings that can ultimately be passed on to farmers.

The future

The integration of genomics into farming practices is more than just a scientific advancement – it’s a practical tool for boosting productivity, improving crop resilience, and maximising the efficacy of biostimulant applications.

By harnessing the power of genomics, farmers can make more informed decisions, optimise product usage, and ultimately achieve better yields and profitability. As John Haywood puts it, “this targeted approach reduces risk and enables more strategic farming decisions. With ongoing research into gene pathways, nutrient dependencies, and optimal application timing, genomics is shaping the future of sustainable, profitable agriculture.”

-

UK National Action Plan Overlooks Biologicals – WBF Urges Regulatory Reform

The UK Government’s revised National Action Plan (NAP) for the Sustainable Use of Pesticides (2025) was published to reduce pesticide risk and promote more sustainable crop protection practices. However, for the World BioProtection Forum (WBF)—the voice of the biologicals industry—this plan represents a critical missed opportunity. While the NAP recognises Integrated Pest Management (IPM) as a key element of the UK’s sustainable agriculture vision, it fails to address the fundamental enabler of IPM’s success: the availability and adoption of biological crop protection products.

Without Biologicals, IPM Cannot Succeed.

Biological solutions, including biopesticides, microbial products, and natural repellents, are cornerstones of modern Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies. However, outdated, slow, costly regulatory systems hinder their integration into UK agriculture.

The NAP promotes IPM but does not provide a pathway to ensure farmers can access the tools necessary for its implementation. This oversight makes the plan aspirational rather than actionable. WBF warns that IPM cannot function effectively without a strong pipeline of registered biologicals to replace withdrawn chemical pesticides.

Biologicals Still Trapped in a Chemical Framework

Despite widespread scientific agreement that biopesticides are safer, break down more quickly, and pose significantly less risk to human health and the environment, they are still evaluated under a regulatory system designed for synthetic chemicals.

The UK continues to operate under EU Regulation 1107/2009, a framework that subjects all pesticide products—regardless of their risk profile—to the same level of scrutiny. Consequently, biologicals may take 4 to 5 years to register in the UK. In the EU, this process can extend even longer—6 to 7 years—without prioritising low-risk solutions.

In stark contrast, Brazil and other Latin American countries have embraced progressive regulatory models that permit the assessment and approval of biologicals in as little as 12 months. These frameworks are based on risk proportionality, facilitating swift adoption without sacrificing safety or efficacy.

DEFRA Must Act Now

The WBF has engaged with DEFRA and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) for several years to highlight this area’s lack of regulatory innovation. In March 2024, the Forum hosted a Westminster conference in 2023 with policymakers, researchers, and industry leaders to present clear evidence and offer practical solutions. The message was consistent and unified:

“Biologicals must be prioritised, and the UK should establish a dedicated, fast-track registration pathway that acknowledges their low-risk status and crucial role in sustainable farming.”

The WBF has also published a White Paper outlining how the UK can reform its regulatory approach post-Brexit. Unfortunately, the NAP fails to reflect any of these proposals, nor does it reference the need for timelines, provisional authorisations, or support for innovation in the biological space.

Farmers Face a Dangerous Gap

Chemical pesticides are being phased out due to environmental and health concerns, but there is no rapid system to fill the gap with biological alternatives. This widening void makes farmers vulnerable—unable to access new solutions yet restricted from using conventional ones.

WBF Chair and Founder Dr. Minshad Ansari warns:

“We are heading toward a future where UK farmers will be left without effective tools to manage pests and diseases. If the government continues to delay biopesticide reform, it will threaten food security, environmental targets, and international business.”

The Call for a Five-Point Reform Plan

To unlock the potential of biological crop protection, the World BioProtection Forum is urging the UK Government to implement the following reforms without delay:

1. A Dedicated Biologicals Strategy

Introduce a national policy and funding framework that prioritises developing, commercialising, and adopting biological crop protection products.

2. A Fast-Track Registration Pathway

Develop a risk-based, proportionate regulatory process for biopesticides, aiming for a timeline of 12–18 months, modelled on international best practices.

3. Post-Brexit Regulatory Independence

Depart from EU Regulation 1107/2009 and create a UK-specific framework designed for the unique characteristics of biological products, utilising science-based risk assessment.

4. Support for SMEs and Innovation

To accelerate innovation, offer technical and financial support to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), including grants and reductions in registration fees.

5. Demonstration and Adoption Programmes

Initiate government-supported on-farm trials, public procurement programs, and demonstration projects to assess the effectiveness of biologicals and promote farmer adoption.

The Time for Consultation Is Over

The biological sector does not seek shortcuts or diminished safety standards. It demands fairness, clarity, and urgency—a system that aligns regulation with risk and innovation with opportunity.

The UK has the chance to become a global leader in sustainable crop protection and post-Brexit regulatory reform. But this cannot happen if we continue to delay the registration of solutions already proven safe, effective, and aligned with our climate and biodiversity goals.

WBF Remains Committed

The World BioProtection Forum will continue to advocate for a more progressive and science-aligned regulatory framework. We remain committed to working with DEFRA, HSE, and UK policymakers to develop a modern system that empowers innovation, protects public health, and ensures farmers can deliver secure and sustainable food production.

Until then, the message is clear:

Without biologicals, the goals of the NAP—and the future of IPM—cannot be achieved.

For media inquiries, quotes, or interviews with Dr. Minshad Ansari, contact:

📧 wbf@worldbioprotectionforum.com

🌐 www.worldbioprotectionforum.com

-

Farmer Focus – Andy Cato

Mar 2025

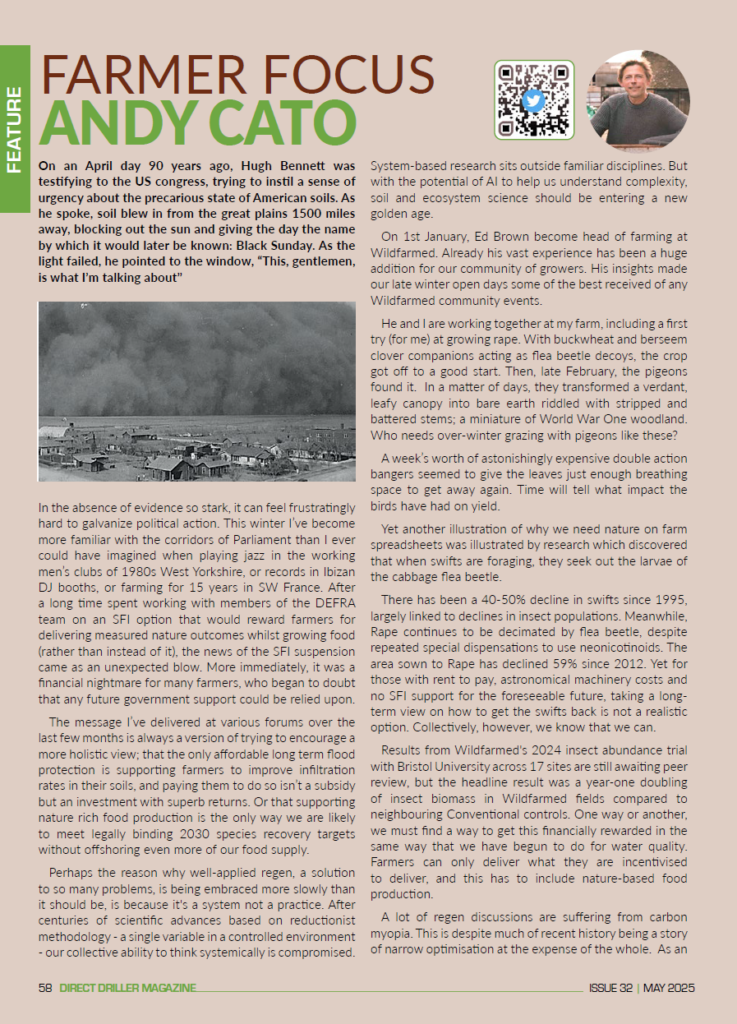

On an April day 90 years ago, Hugh Bennett was testifying to the US congress, trying to instil a sense of urgency about the precarious state of American soils. As he spoke, soil blew in from the great plains 1500 miles away, blocking out the sun and giving the day the name by which it would later be known: Black Sunday. As the light failed, he pointed to the window, “This, gentlemen, is what I’m talking about”

In the absence of evidence so stark, it can feel frustratingly hard to galvanize political action. This winter I’ve become more familiar with the corridors of Parliament than I ever could have imagined when playing jazz in the working men’s clubs of 1980s West Yorkshire, or records in Ibizan DJ booths, or farming for 15 years in SW France. After a long time spent working with members of the DEFRA team on an SFI option that would reward farmers for delivering measured nature outcomes whilst growing food (rather than instead of it), the news of the SFI suspension came as an unexpected blow. More immediately, it was a financial nightmare for many farmers, who began to doubt that any future government support could be relied upon.

The message I’ve delivered at various forums over the last few months is always a version of trying to encourage a more holistic view; that the only affordable long term flood protection is supporting farmers to improve infiltration rates in their soils, and paying them to do so isn’t a subsidy but an investment with superb returns. Or that supporting nature rich food production is the only way we are likely to meet legally binding 2030 species recovery targets without offshoring even more of our food supply.

Perhaps the reason why well-applied regen, a solution to so many problems, is being embraced more slowly than it should be, is because it’s a system not a practice. After centuries of scientific advances based on reductionist methodology – a single variable in a controlled environment – our collective ability to think systemically is compromised. System-based research sits outside familiar disciplines. But with the potential of AI to help us understand complexity, soil and ecosystem science should be entering a new golden age.

On 1st January, Ed Brown become head of farming at Wildfarmed. Already his vast experience has been a huge addition for our community of growers. His insights made our late winter open days some of the best received of any Wildfarmed community events.

He and I are working together at my farm, including a first try (for me) at growing rape. With buckwheat and berseem clover companions acting as flea beetle decoys, the crop got off to a good start. Then, late February, the pigeons found it. In a matter of days, they transformed a verdant, leafy canopy into bare earth riddled with stripped and battered stems; a miniature of World War One woodland. Who needs over-winter grazing with pigeons like these?

A week’s worth of astonishingly expensive double action bangers seemed to give the leaves just enough breathing space to get away again. Time will tell what impact the birds have had on yield.

Yet another illustration of why we need nature on farm spreadsheets was illustrated by research which discovered that when swifts are foraging, they seek out the larvae of the cabbage flea beetle.

There has been a 40-50% decline in swifts since 1995, largely linked to declines in insect populations. Meanwhile, Rape continues to be decimated by flea beetle, despite repeated special dispensations to use neonicotinoids. The area sown to Rape has declined 59% since 2012. Yet for those with rent to pay, astronomical machinery costs and no SFI support for the foreseeable future, taking a long-term view on how to get the swifts back is not a realistic option. Collectively, however, we know that we can.

Results from Wildfarmed’s 2024 insect abundance trial with Bristol University across 17 sites are still awaiting peer review, but the headline result was a year-one doubling of insect biomass in Wildfarmed fields compared to neighbouring Conventional controls. One way or another, we must find a way to get this financially rewarded in the same way that we have begun to do for water quality. Farmers can only deliver what they are incentivised to deliver, and this has to include nature-based food production.

A lot of regen discussions are suffering from carbon myopia. This is despite much of recent history being a story of narrow optimisation at the expense of the whole. As an example, when timber was the main driver of economic growth, pioneering 19th century Prussian tree scientists increased production by overseeing the felling of vast tracts of ancient forests, replacing them with managed, fast growing coniferous monocultures. Their yield and carbon numbers were excellent. It was an ecological disaster.

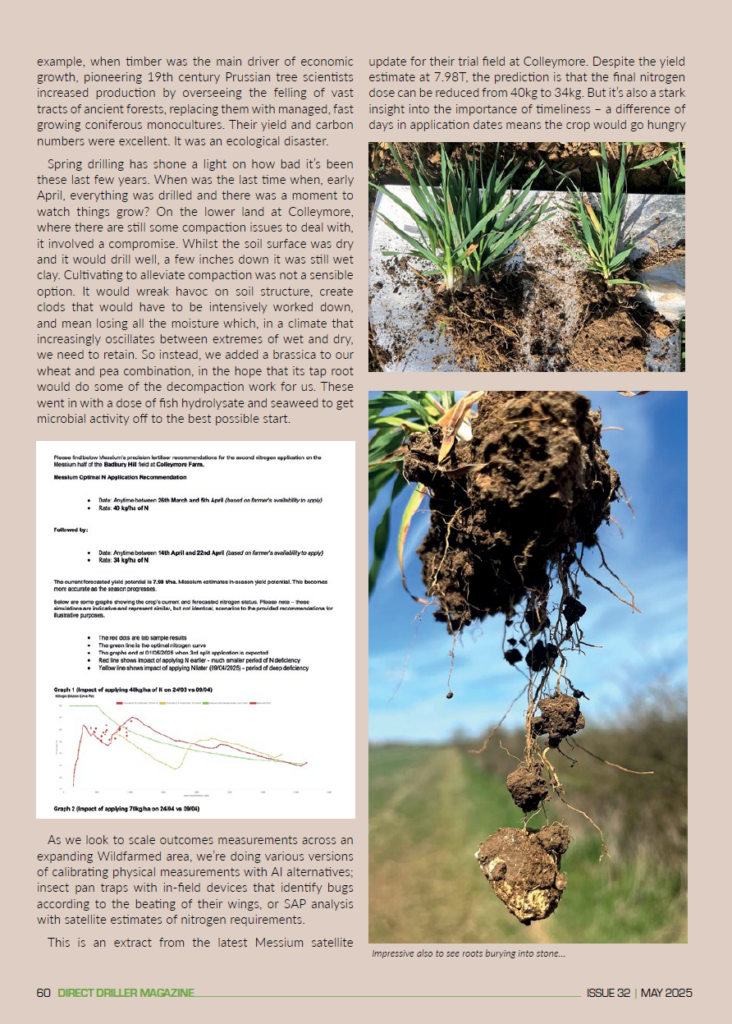

Spring drilling has shone a light on how bad it’s been these last few years. When was the last time when, early April, everything was drilled and there was a moment to watch things grow? On the lower land at Colleymore, where there are still some compaction issues to deal with, it involved a compromise. Whilst the soil surface was dry and it would drill well, a few inches down it was still wet clay. Cultivating to alleviate compaction was not a sensible option. It would wreak havoc on soil structure, create clods that would have to be intensively worked down, and mean losing all the moisture which, in a climate that increasingly oscillates between extremes of wet and dry, we need to retain. So instead, we added a brassica to our wheat and pea combination, in the hope that its tap root would do some of the decompaction work for us. These went in with a dose of fish hydrolysate and seaweed to get microbial activity off to the best possible start.

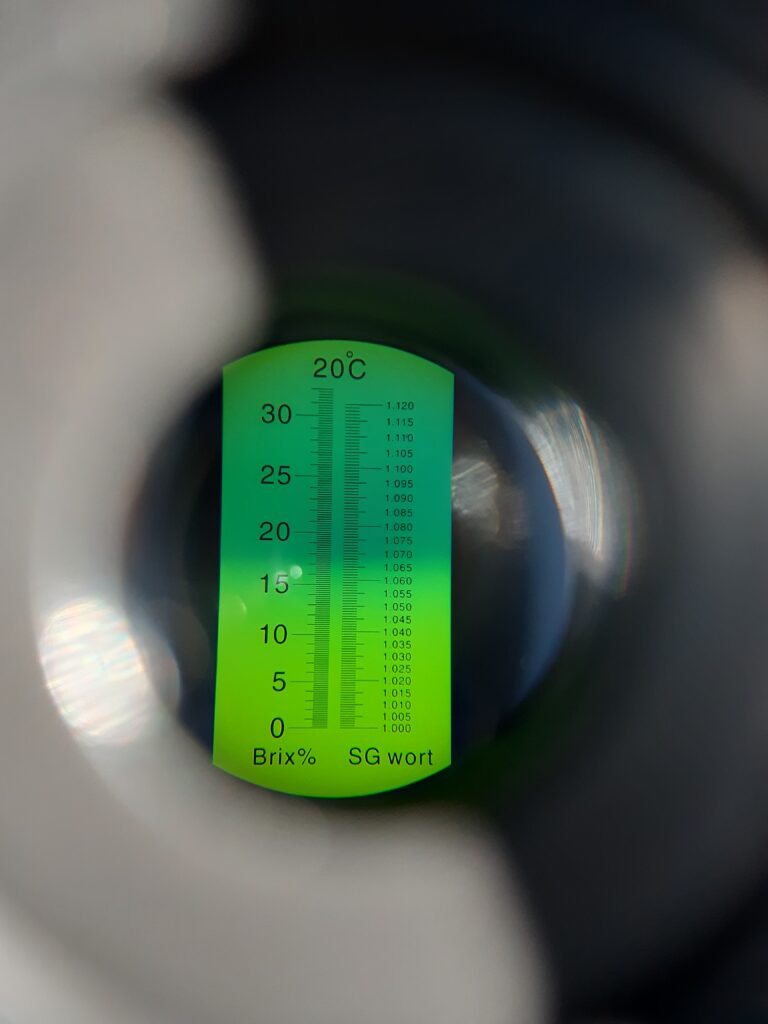

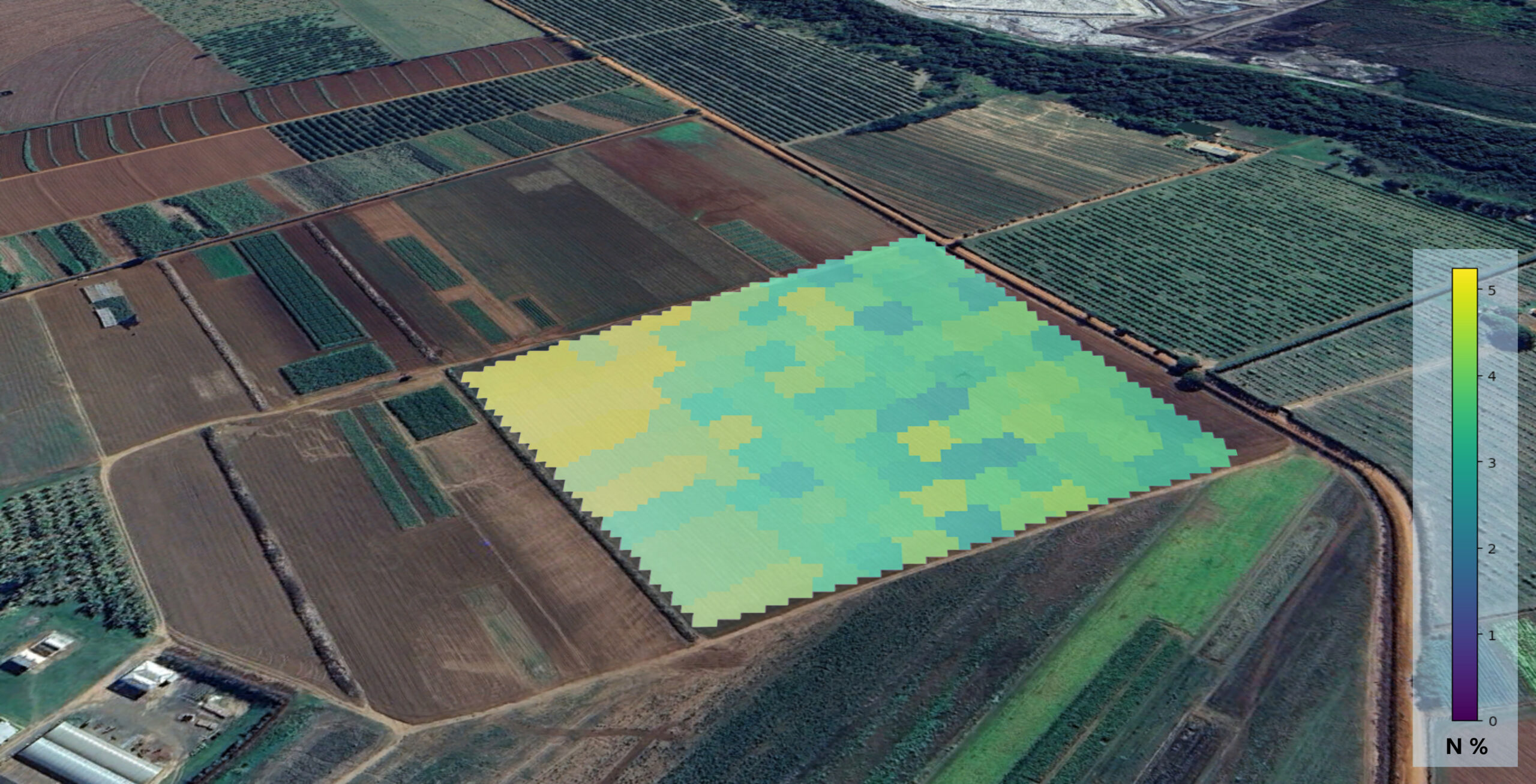

As we look to scale outcomes measurements across an expanding Wildfarmed area, we’re doing various versions of calibrating physical measurements with AI alternatives; insect pan traps with in-field devices that identify bugs according to the beating of their wings, or SAP analysis with satellite estimates of nitrogen requirements.

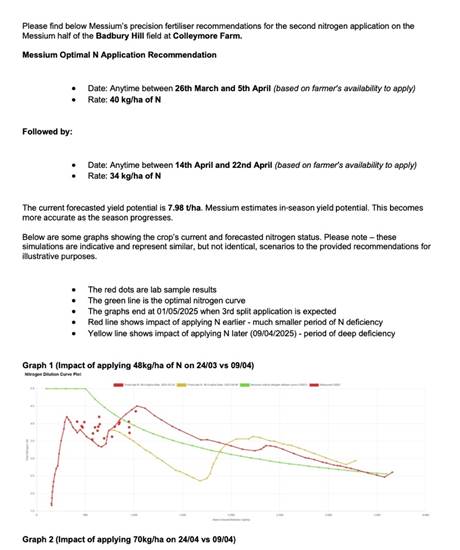

This is an extract from the latest Messium satellite update for their trial field at Colleymore. Despite the yield estimate at 7.98T, the prediction is that the final nitrogen dose can be reduced from 40kg to 34kg. But it’s also a stark insight into the importance of timeliness – a difference of days in application dates means the crop would go hungry at a critical point. We’ll be combining this with a Hillcourt Research flag leaf assessment of crop nutrient levels. Before the plant begins its transfer of nutrients into the grain, we want to see if there is adequate nutrition to hit milling spec. If not, a small amount of foliar N will go a long way to correcting it. “Test, don’t guess” as John Kempf is fond of saying. These two data sets should hopefully remove much of the guessing from a good yield of milling spec wheat grown as efficiently as possible.

At Diddly Squat, a Wildfarmed oat and bean crop followed the summer cover crop described in the last bulletin. With the smaller cover crop seeds drilled too deeply, this inevitably left some spaces which blackgrass was all too happy to fill. But the fields nevertheless had an abundance of worms by autumn, something which even Kaleb was smiling about. The oats and beans, planted with a seaweed application, were also coated with a trial batch of Kempf’s Biocoat gold, a microbial and nutritional seed stimulant. There’s no great difference in plant size, but the difference in soil aggregation compared to the other side of the hedge signposts the cumulative biology of cover crop, inoculant and seaweed.

Impressive also to see roots burying into stone…

We’re using the same small doses of carbon coated N as we are at Colleymore, making sure the nitrogen is used as much as possible by the oats and there aren’t excess nitrates for the blackgrass to feed on.

Avoiding these nitrates is of course as critical for waterways as it is for blackgrass control. The roll out of direct-to-Wildfarmed-grower payments from Water Companies continues. Since the last update, Harriet, Rob and the team have now reached agreements with 6 of the 9 biggest providers.

In a show of solidarity that feels sadly distant today, Crew town hall, March 1936, saw 500 representatives of the County Health Authorities, the Farmers’ Union and the medical profession, all gathered to hear the conclusions of Cheshire doctors following their investigation into the nutritional quality of food and its impact on health. The Medical Testament they presented cited reasonable progress in curing disease. But failure in the other half of their brief – preventing sickness.

“yet most of this sickness is preventable and would be prevented by the right feeding of the people. We consider this opinion so important that this document is drawn up in an endeavour to express it and to make it public.”

Informing consumers about the nutritional impact of food grown in living soils is proving to be highly complex. Advertising rules drawn up for a different food system make it very hard to talk about either the absence of toxicity – ie the fact that we test our grain to be free of pesticide residues, or, beyond the basics of fibre, the presence of nutrition

Over the last few years, we’ve measured significant increases in antioxidants in Wildfarmed crops relative to conventional controls. With US company Edacious we’re now taking this into the production process to see what happens to nutritional differences through the milling and baking process.

The Bio Nutrient Institute researched nutritional quality across around 3500 samples of 21 different crops. It’s author, Dan Kittredge, found that:

“despite what you may predict, there wasn’t a clear link between increased nutrient density and the crop being grown in a regenerative or organic-certified system. There was no connection between increased nutritional quality and whether the crop was grown locally, came from a farmer’s market, or a supermarket. Even more surprisingly, nutrient density wasn’t correlated with the levels of macro or micronutrients or carbon in the soil, nor was it correlated with specific regenerative practices…the only factor that consistently predicted increased nutrient density was soil respiration, a key indicator of the amount of life in the soil”

Soil respiration and infiltration are emerging as useful indicators of overall health and are a shorthand perhaps for the connectivity analyses favoured by Andy Neal at Rothamsted, who’s topographical soil videos show subterranean life from a microbe’s perspective. It’s thwarted attempts to move around compacted soils resemble the dark, dead ends of, in Andy’s words, “a 70s housing estate”.

Andy’s recent study at FarmEd shone a light on the endless difficult compromises faced by farmers. After four years of herbal ley, both the fungal / bacterial biomass ratio and soil structure were similar to that observed in undisturbed, permanent pasture. Yet such was the impact of ploughing, cultivation and sowing that, four weeks after planting, the fungal bacterial ratio and structure had reduced to a point where it was no longer significantly different from that observed in the glyphosate managed, continuous wheat plot.

Nicola Canon, professor at the Royal Agricultural University, invited me to speak at her lecture to celebrate the 180th anniversary of the university’s first cohort of 35 students. During the Q&A I was asked what the biggest challenge for Wildfarmed was today. My mind raced with any number of problems we need to solve. But on reflection, it became clear that they are all versions of the same problem. From field to plate, the Wildfarmed team are constantly working with the best available information to optimise the intersection of good farmer outcomes, quality food, nature recovery, and high street affordability. Doing so requires avoiding dogma and embracing nuance. The most difficult challenge of all is embracing nuance in an increasingly binary world. But if we don’t, we won’t solve anything.

-

Regenerating the soils of tomorrow: SoilPoint’s answer to the UK’s Agricultural Crisis

As farmers worldwide face the dual challenges of maintaining productivity while transitioning to more sustainable practices, SoilPoint has emerged as a leading innovator in the field of soil health and regenerative agriculture, transforming agricultural practices across the UK and beyond, helping ensure a sustainable future for farming and food security.

Who is SoilPoint?

SoilPoint Humic Co. began in the USA and has expanded globally into UK and European markets. Led by CEO Alan Forrester, who is Chair of the UK Fresh Produce Consortium (FPC), the company brings together an experienced team of farmers, food industry executives, and soil technology experts. Together, they are tackling one of the most pressing challenges of our time: the rapid depletion of the world’s topsoil.

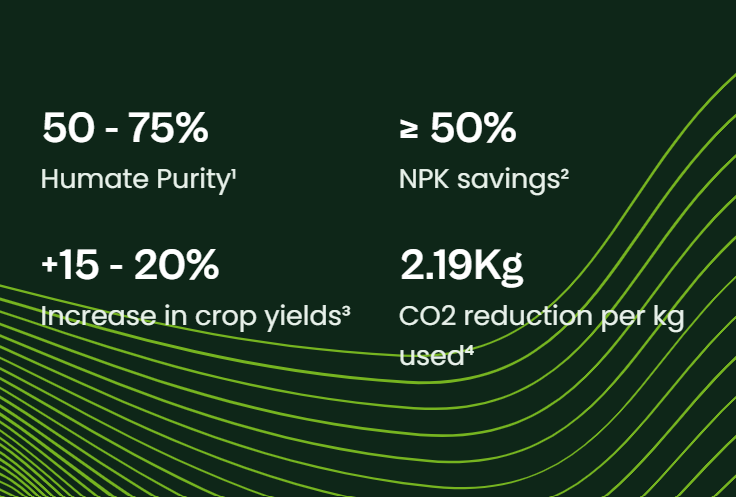

At the heart of SoilPoint’s innovation is their breakthrough Soil Booster – a natural soil conditioner proven to reduce dependence on chemical fertilisers. Certified by the UK Soil Association, Soil Booster contains key macro nutrients as well as 87 essential micronutrients extracted from lignite rock deposits. Using a proprietary process, it achieves 50%-70% pure humic granulates – far exceeding competitors’ 10%-20% concentrations.

Global trials

While conventional fertilisers have been relied upon to provide temporary yield increases, they’ve systematically degraded soil ecosystems worldwide, creating a dependency cycle that threatens long-term food security.

SoilPoint has cracked the industry’s traditional reliance on harsh chemical fertilisers, creating a solution that accelerates topsoil formation and generates up to 1cm every three years or faster, depending on conditions – ultimately proving that higher yields are attainable through sustainable practices that deliver both productive and profitable farming.

Global trials, including studies conducted in the UK, have demonstrated impressive results, boosting crop yields by up to 30%, improving soil water retention, enhancing carbon sequestration in soil and biomass and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in comparison to conventional farming practices.

In March 2025, SoilPoint partnered with Cefetra Ltd, a leading UK Grain business and agricultural supply chain specialist, to launch a pioneering soil health initiative in the UK. This initiative is built alongside 36 forward thinking farmers to replace a proportion of their synthetic fertiliser usage with SoilPoint’s Soil Booster, running for a full crop cycle measuring yields, crop quality, soil health, nutrient availability, and carbon emissions. This partnership marks the first phase of a long-term commercial relationship through which Cefetra will offer SoilPoint’s Soil Booster to UK farmers as part of its product portfolio.

Alan Forrester, CEO of SoilPoint, commented:

“Our data suggests that, if the UK continues to lose soil at current rates, it may face significant threats to future harvests. SoilPoint Soil Booster offers a natural and proven way to rejuvenate soils, supporting productivity and environmental improvements at the same time.

Visit www.soilpoint.earth today to discover the best solutions for your crops. SoilPoint’s Soil Booster is available as either a granule or a fine power, compatible with your existing nutrition and crop protection delivery methods.

-

Farmer Focus – David Aglen

Mar 2025

Reflections on learnings and change.

We are moving on to pastures new, after nearly 15 years at Balbirnie Home Farms in Fife, I have taken up a post managing an arable farming business a bit further north that has yet to begin the adventure that is regen ag. This is a great time to look back on what we have achieved and most importantly learned, as we changed a business to rely less on synthetic inputs, and more on what nature would provide. Don’t misunderstand me here, we were still far from organic on the arable front, but had made big inroads to reducing fungicide usage. Herbicides, on the other hand are a bigger challenge, I struggled to reach the eutopia of a cover crop that could be successfully crimped down as the next crop was sown. I think the first crops to be grown like this commercially in the Scotland are likely to be some form of brassica vegetable. The technology exists, we just need the will to give it a go.

Direct drilling has been both challenging at times, and hugely rewarding at other times. There is no doubt that the financial savings are real. The soil and environment have benefited hugely as well. Seeing the drains running with clean water in the winter is very satisfying, especially so when the drains from a nearby cultivated field may be running with dirty water at the same time. What we now know is that no-till needs to be balanced with judicious use of appropriate of cultivation, and dare I say it, the plough.

Changes with the livestock side of the business have been equally dramatic. We have moved from a hugely intensive system, where cattle were housed for most of the winter to one where all stock classes are never housed. The cost savings have been staggering.

Cattle are now far more integrated into the arable side of the business, grazing cover crops as the opportunities arise, and even replacing a portion of combinable crops as an enterprise competing for land, where the margin per hectare is attractive, and that is before we even consider the fertility and soil health benefits.

It has not all been plain sailing, reducing nitrogen inputs has been a greater challenge. I have concluded that, in the short term, this needs to be that last input that is reduced. We just need to find ways to minimize the waste that is inherent in the use of artificial N as well as growing and building more nitrogen building crops into our rotation. Perhaps these will take the form of summer cover crops cycled through livestock to generate an income, or more efficient ways to apply the artificial N that we do need to use.

Finding a good rotation has been challenging also. Vegetables and potatoes produce a good income stream and are good break crops, whether that be grown ourselves or renting out fields to others. The requirement for intensive cultivations is not so good though and seems to set the soil back a few years afterwards. The reality is that these crops are a food source and so need to be grown, the aim is to build the soil health back up again in the intervening years. This is where the judicious use of cultivation comes in to get the following crop established well to start the healing process, allowing the direct drilling to resume the second season after veg.

Of course, none of this would have been possible without the support of the Balfour family in allowing me to try things that were a bit different. And of course the team I leave behind, who have worked beside me, Colin Black and Grant Ross. Over the years they have had to endure endless experiments and mad ideas, as well as adding their own at times. Thank you all very much for the help and support over the years, and I wish you all the very best for the future.

And so now it is exciting to embark on a new challenge. Smaller in scale than I have been used to, and with no cows for the time being (looking forward to a few more weekends off though), but, size isn’t everything. I will be leaning on my peers in organisations such as BASE-UK to offer helpful suggestions as to how we proceed as the pressure both financially and environmentally is increased on our industry. I have no doubt that I will be hosting farm walks in the future, allowing me to pick peoples brains for new suggestions.

-

Agronomist in Focus – Harry Molton

“Roots, Rotation and Resilience: The first steps to a more productive and profitable future.

The need for a more resilient and productive farming system is clear, but moving forward requires a shift from short-term yields to long-term sustainability.

Transitioning to a regenerative or more sustainable system involves practices that rebuild soil health, enhance biodiversity, and improve climate resilience. Whether it’s cover cropping, rotational grazing, or reducing synthetic inputs, every step towards regeneration leads to a more productive and profitable future.

However, this transition requires careful planning and a willingness to embrace change. At Indigro, we’ve helped many clients on this journey. Here are the key steps to help you get started.

Understanding the Principles

Regenerative agriculture begins with minimising soil disturbance. On many soils, this takes time — few in the UK can switch from conventional tillage to direct drilling overnight. Building soil structure gradually is key to supporting no-till.

Our second regenerative principle is maintaining soil cover all year. Cover crops fill the gap between cash crops — such as between winter wheat and spring barley. Catch crops or summer covers can make use of long summer days to drive photosynthesis, increasing soil organic carbon.

We’ve also seen success establishing clover understories, which help maintain cover, suppress weeds, and improve diversity.

Clover Understory Maximising Diversity of both cash crops, and cover crops boosts biodiversity – another key facet of regenerative farming. While cover crop mixtures are easily tailored, consider adding a companion crop to increase the diversity within the cash crop. If flowering species are chosen, they can also provide a pollen source for invertebrates.

Diverse rooting systems play a vital role – taproots break compaction, fibrous roots condition soil. Maintaining living roots in the soilat all timesallows your soils to thrive. Fields or areas of fields left fallow can deteriorate, affecting soil health and subsequent crops.

Finally, where possible, integrate livestock into the farming system.

These principles form the foundation of regenerative farming. At Indigro, we see them as good farming practices — guidelines to support decision-making, not rigid rules. Especially in the early stages of moving towards a more sustainable system. It’s about making steady progress, not achieving perfection from day one.

Start with Assessment

When advising a transition to a regen system, we start with a thorough farm assessment.

Firstly, review drainage plans, check drain condition, fix issues, and mark outfalls. We carry out a Record of Condition (RoC) alongside Visual Soil Assessments (VSAs), looking at compaction layers and recording earthworm numbers.

Earthworms are the excavators, decomposers, and cultivators of our soils — a hidden workforce driving soil health. Their presence offers insight into soil condition, with studies showing they can contribute up to 25% of yield increases in sustainable systems.

In-depth soil analysis helps to identify problem areas and creates a baseline for progress. Understand your topography, erosion risk, rotation history, available equipment, and labour. The more you know at the start, the easier it is to measure improvement.

Use Cover Crops as a Starting Point

Cover crops are one of the simplest ways to begin. They improve soil biology, manage weeds, prevent leaching, and boost organic matter. The key is to define your objectives first; that will guide the right seed mix, tailored to your soil type and desired outcome. This may change from one year to the next.

Most farms already include spring crops, so an overwinter cover crop is a logical entry point. Choose a seed mix suited to your farm and objectives—legumes for nitrogen fixation, buckwheat for phosphate, deep-rooters for compaction etc.

Drill covers promptly after harvest, into moisture, and with care. Seed mixes contain different sizes that separate in transit or hoppers, so fill the drill little and often. Depth should suit the smallest seeds or use split hoppers to drill separately.

Covers should be managed like cash crops — timeliness, seedbed prep, and slug control matter.

Winter Cover Crop Soil Structure Appropriate Tillage

When you first decide to begin your regenerative journey, it can be very tempting to acquire a shiny new direct drill. However, eliminating tillage overnight is often impractical and does not achieve the desired outcome.

We often talk about “earning the right” to no-till. This refers to ensuring your soil can support a no-till approach through good soil structure and drainage. Gradually reducing tillage over time will help you build the required structure and resilience in your soils to allow no-till.

Diversity in plants is key to a regen system, as is, diversity in tillage. This doesn’t mean changing tillage approach year-on-year, but addressing problems based on their needs.

If turning headlands are compacted, low disturbance sub-soiling will help alleviate this issue. If grassweeds are an issue, utilising stale seedbeds prior to drilling is wise. A light disc or straw rake may help. And in some cases, even ploughing may be the right tool for the job.

While ploughing isn’t associated with regenerative agriculture, it can have a place. Achieving the best crop establishment is key and we therefore must choose the most appropriate cultivation to achieve this. Risking having bare ground, is arguably more damaging to soil health than a well-considered appropriate cultivation.

Focus on outcomes rather than dogma. Strategic use of cultivation can help set a farm on the path to a more resilient, regenerative system. The key is to use these tools deliberately and sparingly, always with the end goal of long-term sustainability. Each farm’s soil type, cultivation history and cropping system will influence how long it takes to move to a no-till system.

Boost Farm Biodiversity

Monocultures have been shown to deplete soil health and increase pest and disease pressure, so increasing biodiversity is central to regenerative farming.

Introducing a variety of plant species supports microbiology and reduces reliance on chemical inputs. Bi-cropping, variety blends, catch and cover cropping are great tools.

Winter Cover Crop In combinable crops, focus on diversifying rotations and integrating livestock.

Soil microbial activity can be enhanced by the integration of livestock. Rotational grazing of cover crops and or cereals accelerates soil health improvements and reduces reliance on inputs, as well as recycling nutrients. If direct integration isn’t feasible, partnering with a local livestock farmer might be an option.

Be Patient, Think Long-Term

Perhaps the most important principle to remember when transitioning your farm is that regenerative agriculture is not a one-size-fits-all approach. What one farm sees as regenerative, may look very different to another’s system — and that’s okay.Success lies in finding what works for your soils and your business.

One of the best things you can do is to assess your soils by eye — dig holes, get your hands dirty, and build a feel for what you’re seeing. That intuitive understanding becomes your personal benchmark, helping you track progress in a way that no report ever could.

Alongside that, monitor soil health indicators, crop performance, and input costs. Use tools like soil testing, infiltration tests, and aerial imagery to guide decisions.

Build flexibility into your strategy and be prepared to adapt. There’s a growing network of farmers across the country all on this journey — tap into it. Above all, be patient. Regenerative farming is a long-term shift. Challenges are inevitable, but improved soil health brings reduced inputs, greater resilience to weather extremes, and ultimately, more consistent yields — all contributing to a more sustainable future.

-

New living mulches guide to help boost soil health and farm resilience

Farmers looking to enhance soil health, increase resilience, and improve sustainability now have a powerful resource at their fingertips.

The newly released Agricology Living Mulches Technical Guide provides clear, practical advice on implementing living mulch strategies that deliver tangible benefits across farms of all sizes.

Living mulches are semi-permanent legume understories sown beneath cereal crops in the first year. By the second year, once the cover crop mulch is well established, new crops are direct drilled into it. This method integrates key regenerative agriculture practices, combining elements of intercropping, cover cropping, mulching, and undersowing to enhance soil health and improve biodiversity.

Co-created in response to farmers’ questions, the free-to-access guide builds on four years of research conducted through an Innovative Farmers Field Lab, further studies by the Organic Research Centre, and insights from UK farmers who have trialled living mulches. It is designed to offer clarity and step-by-step guidance on effectively adopting this innovative practice.

When managed effectively, living mulches can improve soil structure and fertility, reduce runoff and erosion, and enhance nitrogen availability for future crops. They can also boost in-field biodiversity, suppress annual weed populations, and lower production costs. However, without proper management, living mulches can also present challenges, including competition with crops, potential yield penalties, and increased perennial weed burdens.

Structured around the farming year, the guide focuses on the living mulch journey season by season – from spring establishment and summer field management, to harvest and autumn transition into a fully living mulch system and concluding with winter mulch management. Each seasonal chapter clearly outlines the actions required, important considerations and potential risks, providing a practical, time-based roadmap to help farmers plan, adapt and trial the system at their own pace.

It concludes with a detailed diary of Matt England’s observations and reflections from trialling living mulches on the Fring Estate in Norfolk over the course of three years.

While there are multiple ways to integrate living mulches, this guide focuses on a low-input system with alternative strategies and additional insights provided for those working within conventional farming systems.

Matt Smee, Head of Agricology at the Organic Research Centre, says that living mulches are a great tool for farmers seeking sustainable and efficient farming practices.

“Every farm is unique, every season brings new challenges, and no two years are the same. With this in mind, the guide provides a framework that allows farmers to tailor living mulch practices to suit their specific needs,” he says.

Along with the guide, an online learning journey exploring different approaches to getting started with living mulches has been created that you can find on the website in the form of the ‘Living Mulch Hub.’ It brings together a wide mix of resources; research papers, videos, tools, blogs and case studies, sourced from the Agricology archive and beyond.

To access the free online learning journey and the full Living Mulches Technical Guide, visit www.agricology.co.uk/resource/living-mulches-technical-guide/

Agricology (www.agricology.co.uk) is an independent knowledge platform that supports all farmers and growers in transitioning to more sustainable and resilient farming systems. It is a free platform open to everyone and was established in response to the increasing challenges of declining soil fertility, climate change, biodiversity loss, and the need to rethink the way land is managed. It brings together research from the field and farmer experiences on using practices that restore the farm ecosystem. These include reducing tillage to improve soil quality, planting cover crops, adding pollinator strips, using trap crops (which divert pests from crops instead of using chemicals), and using agroforestry systems.

Agricology was founded in 2015, is a collaboration between over 40 organisations, and is managed and delivered by the Organic Research Centre.

For more information contact Matt Smee on matt.s@organicresearchcentre.com

-

Farmer Focus – Tim Parton

At the time of writing things are getting dry! Are we in for another dry spring? The last time the moon was in the present orbit was the 1700s and they had the same weather as we are experiencing now (so I read as I am not that old), going from floods to drought. They got through it then so I am sure we will cope! The importance for having healthy soil has never been more significant in my opinion, in order to cope with the extremes we are experiencing.

Fortunately, I am mobile again and have been out giving a lot of talks and on-farm consultancy: so nice to see different people’s approaches around the country, but all aiming to improve their soil while making a profit.

As Green Farm Collective, we launched our flour brand through Eurostar commodities called “Rise”, down at the International Food and Drink show, at the excel building in London. Attention around our certified Regen flour was fantastic! I was asked to speak on a Regen panel while attending with Claire Mackenzie (Six Inches of Soil), Andy Neil (Rothamsted research), Dave Smith (Fielden’s whiskey) and Henry Astor (Bruern Farm). Henry supplies Fielden whiskey with rye and wheat farmed with no cides.

We had great fun on the panel with lots of interest from the audience about regenerative produce. Whenever I give a talk to consumers, I always get the question, where can I buy this food? I have never really been able to give an answer but now finally I can say, here! This is just the start in my opinion; the right education needs to be given, and full transparency needs to occur. Consumers should have the right to see the full journey of their food and have the right to be part of the story helping to heal the planet in which we live. Change in my opinion always comes from the people; as together we do have power. Just the same, it’s always been one of my aims to unite farmers across the world as together we have power but as individuals, we have very little.

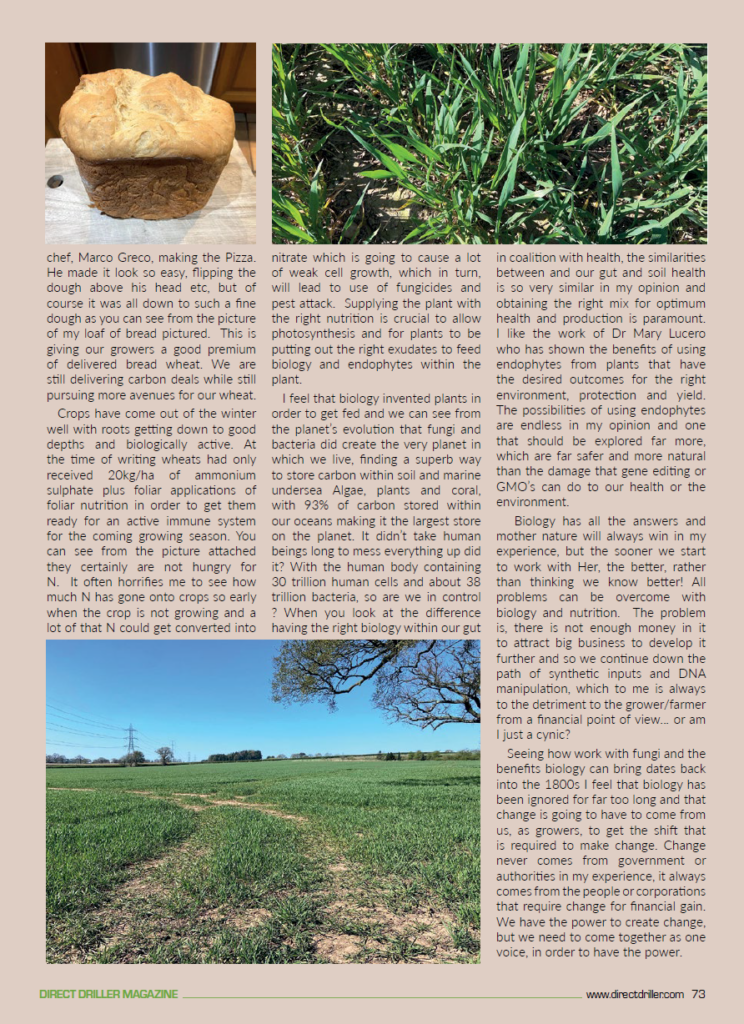

Tasting the pizza made from our flour was a true delight and one of the best pizzas I have ever had, which was probably helped along by the fact that the much-acclaimed Italian pizza chef, Marco Greco, making the Pizza. He made it look so easy, flipping the dough above his head etc, but of course it was all down to such a fine dough as you can see from the picture of my loaf of bread pictured. This is giving our growers a good premium of delivered bread wheat. We are still delivering carbon deals while still pursuing more avenues for our wheat.

Crops have come out of the winter well with roots getting down to good depths and biologically active. At the time of writing wheats had only received 20kg/ha of ammonium sulphate plus foliar applications of foliar nutrition in order to get them ready for an active immune system for the coming growing season. You can see from the picture attached they certainly are not hungry for N. It often horrifies me to see how much N has gone onto crops so early when the crop is not growing and a lot of that N could get converted into nitrate which is going to cause a lot of weak cell growth, which in turn, will lead to use of fungicides and pest attack. Supplying the plant with the right nutrition is crucial to allow photosynthesis and for plants to be putting out the right exudates to feed biology and endophytes within the plant.

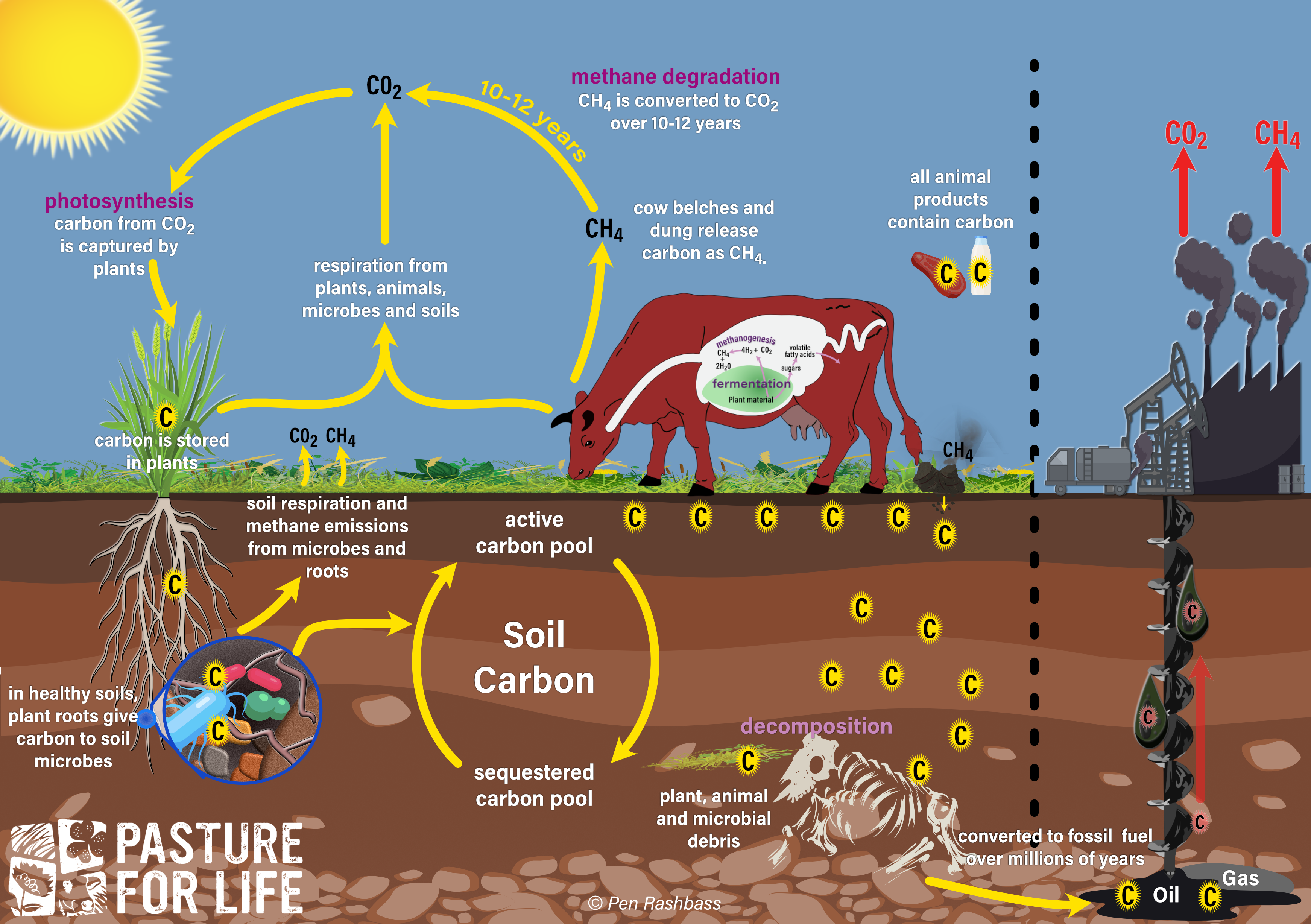

I feel that biology invented plants in order to get fed and we can see from the planet’s evolution that fungi and bacteria did create the very planet in which we live, finding a superb way to store carbon within soil and marine undersea Algae, plants and coral, with 93% of carbon stored within our oceans making it the largest store on the planet. It didn’t take human beings long to mess everything up did it? With the human body containing 30 trillion human cells and about 38 trillion bacteria, so are we in control ? When you look at the difference having the right biology within our gut in coalition with health, the similarities between and our gut and soil health is so very similar in my opinion and obtaining the right mix for optimum health and production is paramount. I like the work of Dr Mary Lucero who has shown the benefits of using endophytes from plants that have the desired outcomes for the right environment, protection and yield. The possibilities of using endophytes are endless in my opinion and one that should be explored far more, which are far safer and more natural than the damage that gene editing or GMO’s can do to our health or the environment.

Biology has all the answers and mother nature will always win in my experience, but the sooner we start to work with Her, the better, rather than thinking we know better! All problems can be overcome with biology and nutrition. The problem is, there is not enough money in it to attract big business to develop it further and so we continue down the path of synthetic inputs and DNA manipulation, which to me is always to the detriment to the grower/farmer from a financial point of view… or am I just a cynic?

Seeing how work with fungi and the benefits biology can bring dates back into the 1800s I feel that biology has been ignored for far too long and that change is going to have to come from us, as growers, to get the shift that is required to make change. Change never comes from government or authorities in my experience, it always comes from the people or corporations that require change for financial gain. We have the power to create change, but we need to come together as one voice, in order to have the power.

-

Pasture for life growing on many fronts

Pasture for Life, which champions the restorative power of grazing animals, continues to go from strength to strength with ambitious targets of hitting 5,000 members farming one million hectares by 2029.

Last year saw 208 events delivered and 93 farmers trained as grazing mentors helping 166 mentees. There was activity across England, Scotland and Wales, including research collaboration and partnerships, as well as successful supply chain initiatives.

Former director Sara Gregson talks to two Pasture for Life certified producers and reviews a couple of recent research projects…

Pasture for Life farmers

Sonja and Perin Dineley

Dorset

Sonja and Perin Dineley regard themselves as biological farmers, creating healthy living networks in the soil and above ground, whilst producing good food for people to eat.

They run 3,000 New Zealand Romney ewes across 750 hectares on three farms close to Shaftesbury. There is a wide range of soils including chalk, greensand and clay and the farms are at different stages of regeneration.

“Agriculture is not easy at the moment, with the reduction in payments and loss of faith from consumers,” says Perin. “But if we can demonstrate that production agriculture can be integrated with caring for nature, there is plenty of scope for us to succeed and be at the forefront of the future direction for farming.”

The ewes are run in three flocks and lambing starts no later than 10 April to make use of the high quality spring grass.

The lambs are weaned at ten to 11 weeks of age and divided into replacements and breeding stock or killing lambs. They are grouped according to weight and put into the most appropriate fields, including herbal leys.

“We have been rotational grazing lambs for several years, achieving growth rates of 400g/day or more,” Perin explains. “They are moved every three to four days on multi-species swards containing a lot of clover, plantain and chicory. Depending on feed availability, a combination of fat lambs are sold through ABP and some store lambs are sold privately.”

No meat is currently sold from the farm, but the Dineleys have recently become Pasture for Life certified in anticipation of doing so in future.

“We have been raising animals on just forage for 30 years or more,” says Sonja. “We need to find a way of getting this nature value through to consumers. Pasture for Life has a lot of direct selling members, and I am sure we can learn a lot from them.”

A small herd of Belted Galloway cross Shorthorn suckler cows has been introduced and their grazing has made a huge difference to biodiversity, with fabulous shows of wildflowers each summer, including fields with hundreds of Bee Orchids.

“We see our work as restoring damaged ground, which is better than merely sustaining it – who wants to sustain really depleted soils?’ asks Sonja. “Forage diversity with different root formations and root depth is critical to rebuilding soil health and that is what we are aiming for.”

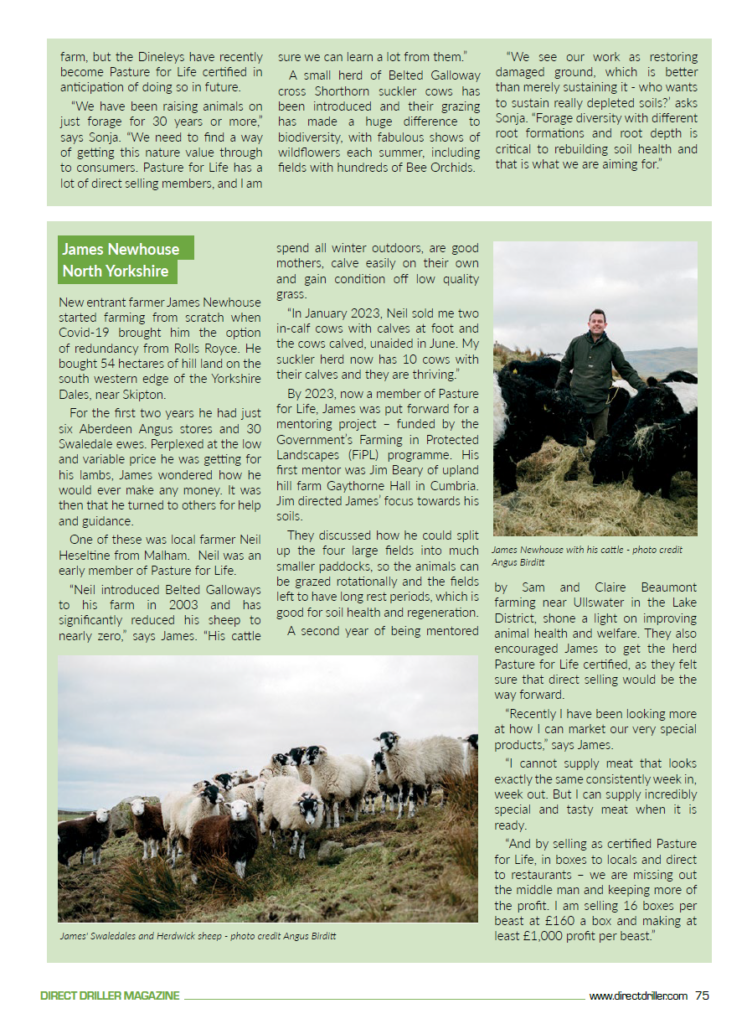

James Newhouse

North Yorkshire

New entrant farmer James Newhouse started farming from scratch when Covid-19 brought him the option of redundancy from Rolls Royce. He bought 54 hectares of hill land on the south western edge of the Yorkshire Dales, near Skipton.