If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

What to do with your carbon?

Written by Thomas Gent from Agreena

Reading this magazine means even if you are not practising regenerative farming I am sure you are at least considering the transition away from ploughing. We of course are also seeing now that the government incentives are going to be rewarding this type of farming, everything seems to be pushing us in this direction.

So the next question that comes to mind in today’s world is what do I do with my carbon?

We need to start thinking about carbon in two separate ways firstly carbon stock, so the existing amount of carbon held on your farm in the soils, trees and hedges etc. This is the carbon that is currently not being traded and is an asset on your farm that you should protect carefully.

Secondly is your additional carbon. This is the carbon that can now be quantified and traded on an annual basis should you choose to do so. This is made up of two separate sections, reductions and removals. Reductions represent the reduction in GHG (GreenHouse Gas) emissions for example by burning less diesel or using less artificial fertilisers. Removals represent the act of taking carbon out of the atmosphere and adding it into your soils, for example by growing a cover crop.

This annual additional carbon compared to a baseline is what carbon programs are looking to help farmers quantify. It should be thought of as a second crop, so at harvest when travelling through the field with the combine you are going to be harvesting the grain crop whilst simultaneously finishing your carbon crop harvest for that year. Just like a crop of wheat the annual yield of a carbon crop depends on the actions you take in the field to improve it over the year and just like a wheat crop post carbon harvest you can choose how best to use that asset.

There are currently a few options that exist for what to do with your carbon certificates.

- First and usually most obvious one is that you can choose to monetise. There are companies that are looking to purchase high quality carbon certificates from local farmers. Depending on the program you join you may have the flexibility to sell these carbon certificates yourself or you can usually ask the carbon program to assist you with this.

- Secondly, holding onto your carbon certificates. Carbon certificates do not expire instantly; they can be held for multiple years. Some farmers I know are holding onto the certificates because they are betting that the price will rise and others are utilising the carbon within their own operations to maybe offset the emissions from another part of the estate. Either way with some programs you can choose to hold the certificates and only choose to sell when the price is right for you.

- Thirdly and most interestingly in the future will be the option to gain premiums for your produce. We are starting to see the emergence of this as a viable option but it is not yet something commonplace or operational at scale.

On my farm I have completed two carbon crop harvests, the first one in 2021 which I chose to monetise as there was no other option of what to do with the carbon that year. Second is from the 2022 harvest which I will probably choose to also monetise as there is no further option. For my coming 2023 carbon harvest I am hoping there will be an option to use the certificates along with my grain.

The important conclusion to the above is to understand that a farmer can issue carbon certificates yearly therefore by not joining a carbon program you are simply missing out on a harvest. We see no options in the market for farmers to backdate and issue carbon for previous years and no likelihood that a method for this will exist.

A farmer who is eligible for a carbon program (not ploughing) who is not part of a carbon program is missing out on harvest. As a farmer you are most likely already taking some of the actions that would help you issue carbon certificates therefore you should look to produce a carbon certificate for this to evidence the actions you have taken that year even if you are not looking to trade.

-

Direct Drilling Offers Savings for both the Farmer and the Environment

WHERE IT ALL STARTED

Growing up on a Canadian prairie farm previous to the 1980s, the term summer fallow was as common as wheat. Every farmer factored summer fallow into the farm crop rotation, often 50% of the land was left to rest while the other half was cropped. Resting land was prone to weed growth so the best way of controlling those weeds was to head out with the cultivator and turn the field black, many farmers took pride in “keeping that summer fallow black”. If mother nature decided to have a dry summer, it was not a good situation. The ditches would fill with your valuable topsoil and if the rain came it would erode the soil carving new ditches through the fields. No till farming pioneers started experimenting in the early 1970s, but the technology needed to take it large scale simply did not exist yet.

Finding new and better ways to grow the crops needed for the world’s ever-growing population became the daily focus of successful crop farmers around the world. Many methods that have been used successfully in the past were now becoming too costly, to both the farmer and the environment. These costs have given rise to the development of new and better equipment and techniques in the agricultural industry. The most exciting involves the now widely accepted practice known as direct drilling or no-till farming.

WHAT IS DIRECT DRILLING?

Basically, it is defined as a method that does not require the soil to be disturbed prior to planting. Direct drilling allows seeds to be planted directly into the soil with no prior need for plowing, tilling, and furrowing. When done on the large scale necessary for crop farming, the technological advances in the machinery used for the process of direct drilling can combine tasks, such as the application of fertilizer, effectively allowing the farmer to make just one pass through the field.

WHY IS DIRECT DRILLING GAINING POPULARITY NOW?

Soaring fuel and labor costs are applying pressure on farmers who have previously experienced success using the old, labor-intensive methods of plowing, tilling, and transplantation. In addition to struggling with these issues, scarcity of rainfall is causing water tables to fall significantly in many of the major crop-producing regions, further impeding the ability of farmers to irrigate their crops.

WHAT OTHER BENEFITS CAN DIRECT DRILLING PROVIDE?

Equipment costs are a huge part of any crop farmer’s operating budget, especially maintenance and fuel costs. Direct drilling allows these farmers to drastically reduce the number of hours these machines are used by cutting down the number of passes made through each field. This extends the life of the machinery, while significantly reducing the cost of fuel, maintenance, labor, and downtime that can severely impact the profit margin.

IS DIRECT DRILLING BETTER FOR THE SOIL?

Direct drilling provides equally important benefits to the health and vitality of the soil. When fewer passes are made through each field with heavy tractors and equipment, there is less compaction of the soil. This helps preserve the health of beneficial microbes in the soil, as well as the organic matter that provides nourishment to the crops that will grow there.

CAN DIRECT DRILLING HELP WITH EROSION?

Soil that has been plowed and tilled into powdery consistency cannot defend itself against the winds and torrential rains that seek to blow or wash it away. Direct drilling allows the natural organic material of the soil to be maintained, keeping the soil surface stable and unharmed by wind and heavy rain. In addition, this organic material helps hold moisture during periods of reduced rainfall and helps it better absorb the rains, when they do come.

With benefits such as these, it is no wonder that direct drilling technology is emerging as one of the shining stars wherever high-volume crop production is desired, in an affordable and earth-friendly manner.

WHAT IS DUTCH OPENERS’ PART IN HELPING PRODUCERS ACHIEVE THEIR DIRECT DRILLING AND NO TILL FARMING GOALS?

Over the last 30 years, Dutch Openers have been working directly with farmers to produce seed openers that are geared toward direct drilling. Innovations such as our Universal Series openers are designed to give farmers accurate seed and fertilizer placement with minimal soil disturbance and are widely used by producers in North America, Australia, and the United Kingdom.

Direct drilling farmers’ needs are not all the same so we offer single row spread tips from 1″ to 5″ widths. We also offer paired row tips from 2.5″ to 5″ row widths offering varying fertilizer depths from 3/8″ below the seed all the way up to 3/4″ below the seed. The Universal Series openers continue to innovate to adapt to new drills and new farming practices to stay current with immerging direct drilling trends.

We have spent the last 2 years building a test facility with the sole purpose of offering producers meaningful innovations that increase efficiencies. Direct drilling was born from the belief that there was a better way to plant the crop, retain moisture, and build nutrients into the soil through sustainable new farming practices. Dutch Openers is committed to continuing our work with producers, understanding their seeding struggles and presenting solutions that make a real difference in the field and their pocketbook.

-

How to cut nitrogen fertiliser use

Written by Rosalind Platt, managing director of UK leaders in crop nutrition, BFS Fertiliser Services. BFS is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year.

Foliar nitrogen fertiliser treatments later in the season can dramatically reduce the total amount of nitrogen needed while maintaining or increasing crop yields.

The recent turmoil in the fertiliser market has been adding to the pressures facing farmers from all sides. Another key farming imperative to move to Net Zero led us at BFS Fertiliser Services to think about how we could help farmers to use less nitrogen while maintaining yields.

Our solution was to develop a foliar nitrogen product called PolyNPlus Foliars. After five years of independent research with one of Britain’s oldest agricultural research centres, NIAB, and international farm managers and agronomists, Velcourt, PolyNPlus has been producing excellent results for farmers. The recent dramatic fluctuations in fertiliser prices have only increased the interest in these products.

What is PolyNPlus foliar nitrogen?

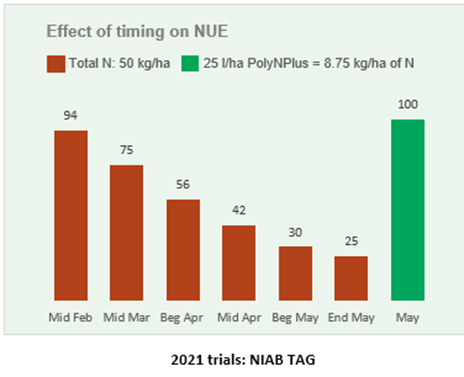

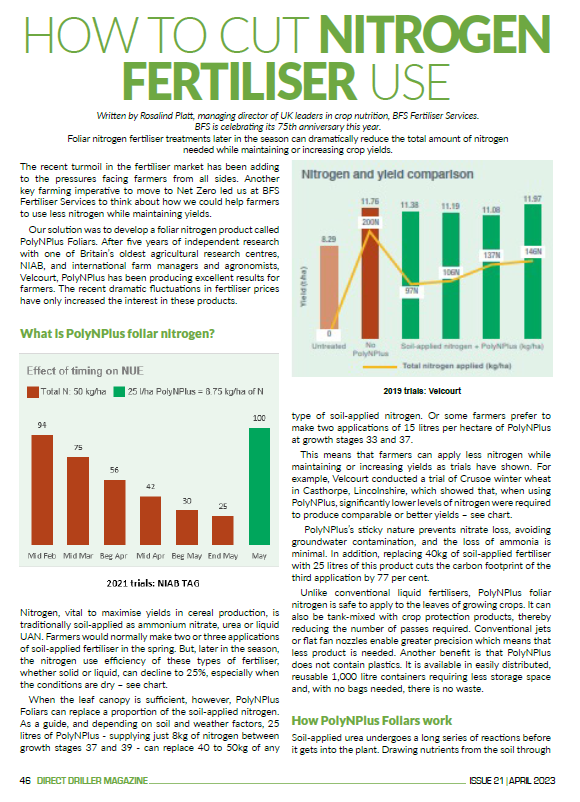

Nitrogen, vital to maximise yields in cereal production, is traditionally soil-applied as ammonium nitrate, urea or liquid UAN. Farmers would normally make two or three applications of soil-applied fertiliser in the spring. But, later in the season, the nitrogen use efficiency of these types of fertiliser, whether solid or liquid, can decline to 25%, especially when the conditions are dry – see chart.

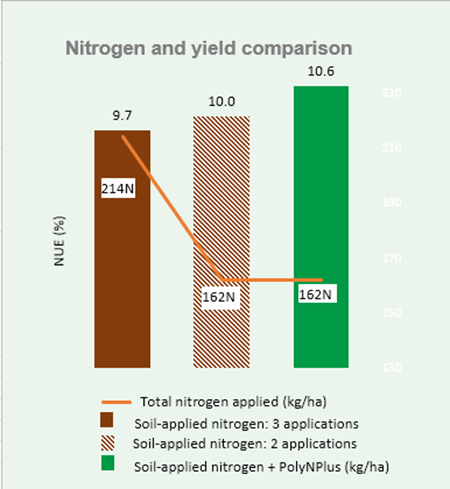

When the leaf canopy is sufficient, however, PolyNPlus Foliars can replace a proportion of the soil-applied nitrogen. As a guide, and depending on soil and weather factors, 25 litres of PolyNPlus – supplying just 8kg of nitrogen between growth stages 37 and 39 – can replace 40 to 50kg of any type of soil-applied nitrogen. Or some farmers prefer to make two applications of 15 litres per hectare of PolyNPlus at growth stages 33 and 37.

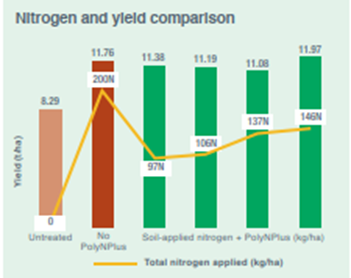

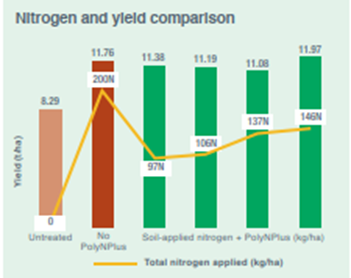

This means that farmers can apply less nitrogen while maintaining or increasing yields as trials have shown. For example, Velcourt conducted a trial of Crusoe winter wheat in Casthorpe, Lincolnshire, which showed that, when using PolyNPlus, significantly lower levels of nitrogen were required to produce comparable or better yields – see chart.

PolyNPlus’s sticky nature prevents nitrate loss, avoiding groundwater contamination, and the loss of ammonia is minimal. In addition, replacing 40kg of soil-applied fertiliser with 25 litres of this product cuts the carbon footprint of the third application by 77 per cent.

Unlike conventional liquid fertilisers, PolyNPlus foliar nitrogen is safe to apply to the leaves of growing crops. It can also be tank-mixed with crop protection products, thereby reducing the number of passes required. Conventional jets or flat fan nozzles enable greater precision which means that less product is needed. Another benefit is that PolyNPlus does not contain plastics. It is available in easily distributed, reusable 1,000 litre containers requiring less storage space and, with no bags needed, there is no waste.

How PolyNPlus Foliars work

Soil-applied urea undergoes a long series of reactions before it gets into the plant. Drawing nutrients from the soil through a plant’s roots requires energy and the plant is not able to take up all of the nitrogen resulting in waste. By contrast PolyNPlus foliar nitrogen is applied directly to the leaf and assimilated into vital proteins.

PolyNPlus comprises molecules of different chain lengths. The shorter ones pass into the leaf quickly while the longer, less soluble ones are released more slowly over several weeks. Because the breakdown process occurs gradually, the plant utilises PolyNPlus most effectively and nitrogen use efficiency is greatly improved.

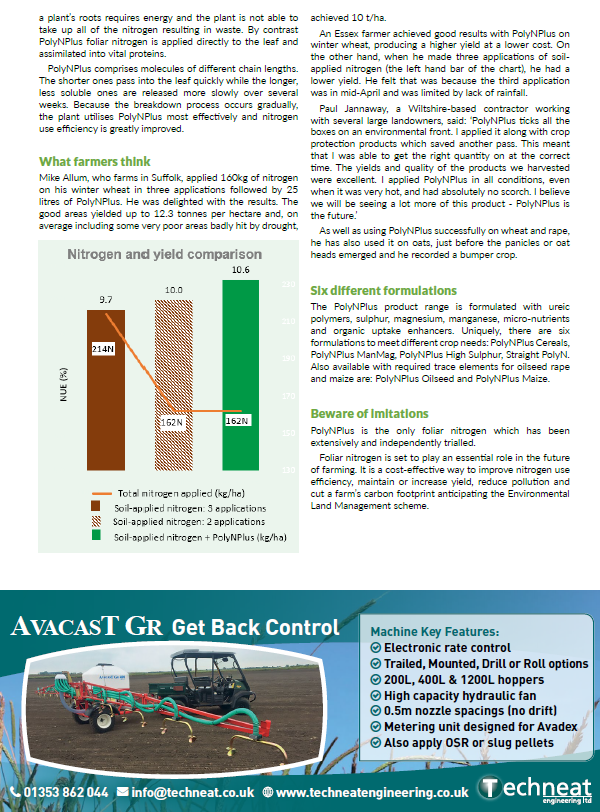

What farmers think

Mike Allum, who farms in Suffolk, applied 160kg of nitrogen on his winter wheat in three applications followed by 25 litres of PolyNPlus. He was delighted with the results. The good areas yielded up to 12.3 tonnes per hectare and, on average including some very poor areas badly hit by drought, achieved 10 t/ha.

An Essex farmer achieved good results with PolyNPlus on winter wheat, producing a higher yield at a lower cost. On the other hand, when he made three applications of soil-applied nitrogen (the left hand bar of the chart), he had a lower yield. He felt that was because the third application was in mid-April and was limited by lack of rainfall.

Paul Jannaway, a Wiltshire-based contractor working with several large landowners, said: ‘PolyNPlus ticks all the boxes on an environmental front. I applied it along with crop protection products which saved another pass. This meant that I was able to get the right quantity on at the correct time. The yields and quality of the products we harvested were excellent. I applied PolyNPlus in all conditions, even when it was very hot, and had absolutely no scorch. I believe we will be seeing a lot more of this product – PolyNPlus is the future.’

As well as using PolyNPlus successfully on wheat and rape, he has also used it on oats, just before the panicles or oat heads emerged and he recorded a bumper crop.

Six different formulations

The PolyNPlus product range is formulated with ureic polymers, sulphur, magnesium, manganese, micro-nutrients and organic uptake enhancers. Uniquely, there are six formulations to meet different crop needs: PolyNPlus Cereals, PolyNPlus ManMag, PolyNPlus High Sulphur, Straight PolyN. Also available with required trace elements for oilseed rape and maize are: PolyNPlus Oilseed and PolyNPlus Maize.

Beware of imitations

PolyNPlus is the only foliar nitrogen which has been extensively and independently trialled.

Foliar nitrogen is set to play an essential role in the future of farming. It is a cost-effective way to improve nitrogen use efficiency, maintain or increase yield, reduce pollution and cut a farm’s carbon footprint anticipating the Environmental Land Management scheme.

-

BASE-UK

BASE-UK is an independent, nationwide, farmer-led knowledge exchange organisation, encouraging members to make agriculture more sustainable by using conversation systems – no-till; cover cropping; integrating livestock; diversifying rotations; using less invasive, cost-effective establishments. Growing Confidence for a Decade!

7th and 8th February 2023 – 10th Anniversary AGM Conference – A Decade of “Growing Confidence!”. What a fantastic turnout we had – of speakers and members! Frederic Thomas opened with a short history of BASE, followed by his view of the future of farming, and how we are best placed to help. A hard act to follow but this didn’t faze Vicky Robinson discussing the findings of her Nuffield Scholarship on Farmer-to-Farmer knowledge exchange. Duncan Wilson, Tom Storr and Elizabeth Stockdale took proceedings up to lunch after which Becky Willson kept everyone energised with her presentation on the work of FCCT. Alastair Leake provided interesting findings from the Allerton Project and Shaun Dowman discussed other sources of income. The day closed with motivational speaker David Hyner.

Wednesday opened with AGM business followed swiftly by a fascinating presentation from Frederic Thomas on carbon, nitrogen, and soil life. Steve Townsend and James Warne then discussed soil chemistry and the importance of the correct balance and nutrition for disease and pest proof crops, respectively. Lance Charity opened after lunch with an insight into his journey as a young farmer and then joined the farmer panel alongside Duncan, Tom, and Frederic. Joel Williams followed with his presentation on growing together and the day closed with Anna Jackson’s energetic talk on working with her father. They haven’t killed each other yet! These presentations were recorded and will be available to members via their profile on the website.

If you would like to know more about how to join BASE-UK, please visit our website: www.base-uk.co.uk

or email Rebecca@base-uk.co.uk We have a wide range of upcoming events, so check out our website calendar.

-

Anglian Water’s Grant scheme supports farmers with innovative ideas to improve soil health and water quality

In Autumn 2022, Anglian Water announced a grant scheme inviting farmers from across the catchment area to apply for funding of up to £7,500 towards innovative ideas that would help them to improve water quality, reduce chemical use and support the improvement of soil health.

A total of 65 farmers were awarded grants for innovation shortly before Christmas and part of the mission is to encourage change of practice for the long term with precision agriculture, reducing pesticide and fertiliser usage, and soil erosion as well as building long term business resilience, with farmers being part of the solution.

Two stand out applications that the water company supported included assistance to Richard Heady, a mixed livestock and arable farmer from Buckinghamshire, with a stubble rake to combat a challenging slug problem. Also Clive Pullin, a dairy and arable farmer from Silverstone on the Northamptonshire / Buckinghamshire border, wanted support with the purchase of a strip till preparator to improve root establishment for his maize cropping.

Talking to Clive Pullin he explains ‘We farm on heavy clay here at Parkfield Farm. Our machinery has to work hard and our diesel usage is high.’

Clive has been adopting a zero till approach to his land management for some years, with some of his peers deeming him as ‘raving mad’ for this method (for adopting innovative farming systems ). Clive was inspired by a trip to Australia, where he saw farmers were using a strip till method to use old roots to retain moisture and reduce soil loss. He thought he could apply this technique to his fields, removing the need to plough, improve drainage, reduce disease risk and top soil loss. Clive commented that ‘he was fed up with seeing his top soil blowing away or heaped up in a corner of the field.’

Clive saw the Grange Machinery Strip Till Preparator at the Midlands’ Machinery show and admired how useful this piece of kit would be in establishing his ‘lazy rooted’ maize crop. With adjustable discs operated from the cab, lightweight, developed and trialled by a small team of farmers, this innovative piece of kit could improve crop establishment, reduce soil compaction and combat the need to use the plough again.

Clive saw the Anglian Water grant advertised in the Thrapston Market Report and discussed a grant application with Anglian Water’s Catchment Adviser. With the grant match funding up to 50% of the cost of the strip till, it has made the initial outlay more palatable and allowed Clive to place an order for the drill. Clive is aware that it will take time to recoup his own financial outlay however he does expect to quickly achieve improved retention of water, soil and nutrients; reducing overall inputs, soil damage and diesel costs.

Kim Hemmings, Anglian Water’s Catchment Advisor for the Tove and Ouse Valley commented ‘We are delighted to support Clive with his grant application. Maize can be a high risk crop because sediment and nutrient losses can be greater than with other arable crops. These losses can result in higher pollution concentrations in raw waters abstracted for drinking water, which increases the cost of water treatment. The use of the drill will build the soils’ resilience to extreme weather conditions, improving soil moisture capacity during drought and the soils’ field capacity to hold water in wetter conditions. In addition, Clive practices multispecies cropping to improve maize protein which further protects against soil and nutrient losses, providing both agronomic and environmental outcomes’.

Similarly with Richard Heady’s application for funding toward a stubble rake, he could clearly demonstrate what benefit the grant would make to his business whilst improving water quality and soil health.

Richard commented ‘ We have a big slug problem and struggle with seed germination after the crop has been drilled. Our combine doesn’t spread the straw effectively and has allowed slugs to be prevalent, eating our cereal crop as it emerges. We have heavy soil and have large bare patches due to slug attack. ‘

Two thirds of the 420ha farm is dedicated to cereals and beans, used to feed his store cattle which he sends to Dunbia for processing. Richard hopes that the stubble rake will destroy the slug eggs by burying them but also removing their opportunity to breed, hence treating the cause not the effect.

Richard has adopted a more holistic approach to his farming methods and is equally hopeful to reduce reliance on chemicals. Long term Richard sees that his crop will have a better establishment, an increase in yields, as well as a reduction in diesel and fertiliser, hence why he is trying to put these controls in place.

‘I saw the grant advertised on Twitter, Richard commented. Anglian Water have been really flexible with being able to choose either a brand new piece of kit or second hand, whatever works best for my farming set up.’

Anglian Water hope to roll out more innovation grants in 2023, opening applications by late Summer which is to be confirmed. You can find out more information by contacting your local catchment advisor or visiting: https://www.anglianwater.co.uk/business/help-and-advice/working-with-farmers/ or follow on Twitter: https://twitter.com/AWCoastCountry

-

Farmer Focus – Phil Rowbottom

April 2023

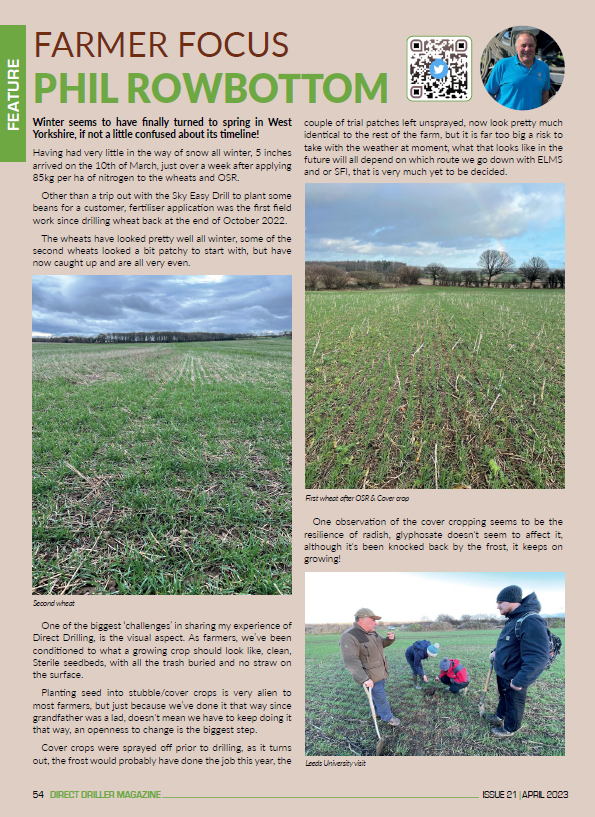

Winter seems to have finally turned to spring in West Yorkshire, if not a little confused about its timeline! Having had very little in the way of snow all winter, 5 inches arrived on the 10th of March, just over a week after applying 85kg per ha of nitrogen to the wheats and OSR. Other than a trip out with the Sky Easy Drill to plant some beans for a customer, fertiliser application was the first field work since drilling wheat back at the end of October 2022. The wheats have looked pretty well all winter, some of the second wheats looked a bit patchy to start with, but have now caught up and are all very even.

Second wheat

One of the biggest ‘challenges’ in sharing my experience of Direct Drilling, is the visual aspect. As farmers, we’ve been conditioned to what a growing crop should look like, clean, Sterile seedbeds, with all the trash buried and no straw on the surface. Planting seed into stubble/cover crops is very alien to most farmers, but just because we’ve done it that way since grandfather was a lad, doesn’t mean we have to keep doing it that way, an openness to change is the biggest step. Cover crops were sprayed off prior to drilling, as it turns out, the frost would probably have done the job this year, the couple of trial patches left unsprayed, now look pretty much identical to the rest of the farm, but it is far too big a risk to take with the weather at moment, what that looks like in the future will all depend on which route we go down with ELMS and or SFI, that is very much yet to be decided.

1st Wheat after OSR & Cover crop

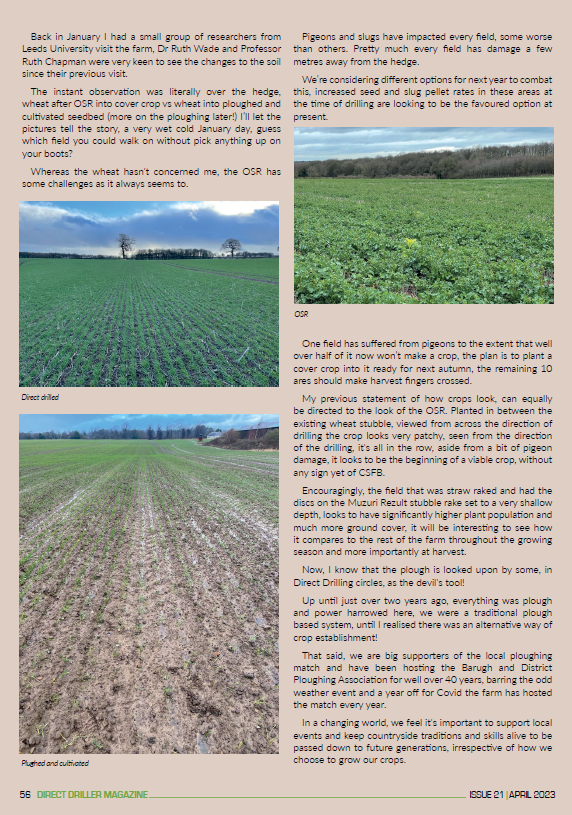

One observation of the cover cropping seems to be the resilience of radish, glyphosate doesn’t seem to affect it, although it’s been knocked back by the frost, it keeps on growing! Back in January I had a small group of researchers from Leeds University visit the farm, Dr Ruth Wade and Professor Ruth Chapman were very keen to see the changes to the soil since their previous visit.

Leeds University visit

The instant observation was literally over the hedge, wheat after OSR into cover crop vs wheat into ploughed and cultivated seedbed (more on the ploughing later!) I’ll let the pictures tell the story, a very wet cold January day, guess which field you could walk on without pick anything up on your boots?

Direct Drilled

Ploughed and cultivated

Whereas the wheat hasn’t concerned me, the OSR has some challenges as it always seems to. Pigeons and slugs have impacted every field, some worse than others. Pretty much every field has damage a few metres away from the hedge. We’re considering different options for next year to combat this, increased seed and slug pellet rates in these areas at the time of drilling are looking to be the favoured option at present.

One field has suffered from pigeons to the extent that well over half of it now won’t make a crop, the plan is to plant a cover crop into it ready for next autumn, the remaining 10 ares should make harvest fingers crossed. My previous statement of how crops look, can equally be directed to the look of the OSR. Planted in between the existing wheat stubble, viewed from across the direction of drilling the crop looks very patchy, seen from the direction of the drilling, it’s all in the row, aside from a bit of pigeon damage, it looks to be the beginning of a viable crop, without any sign yet of CSFB.

Encouragingly, the field that was straw raked and had the discs on the Muzuri Rezult stubble rake set to a very shallow depth, looks to have significantly higher plant population and much more ground cover, it will be interesting to see how it compares to the rest of the farm throughout the growing season and more importantly at harvest.

OSR

Now, I know that the plough is looked upon by some, in Direct Drilling circles, as the devil’s tool! Up until just over two years ago, everything was plough and power harrowed here, we were a traditional plough based system, until I realised there was an alternative way of crop establishment! That said, we are big supporters of the local ploughing match and have been hosting the Barugh and District Ploughing Association for well over 40 years, barring the odd weather event and a year off for Covid the farm has hosted the match every year. In a changing world, we feel it’s important to support local events and keep countryside traditions and skills alive to be passed down to future generations, irrespective of how we choose to grow our crops.

Drilling and Ploughing

-

2017 Nuffield on Carbon: Ahead of the Debate

Carbon is a hot topic at the moment. Whether it’s transitioning to net zero for the UK or supply chains, opportunities to access carbon markets, or comparing the environmental credentials of different products, you can’t get away from the fact that we are all having to get to grips with new terminology and metrics.

Farming is unique in its ability to provide a climate solution. Farming is built on the carbon and nitrogen cycles and, as such, is part of a complex biological system where things move and change depending on seasons, inputs, markets and management. It was this acknowledgement that managing carbon on-farm can be complex which was one of the main findings of my Nuffield report back in 2017. Indeed, a key conclusion was that

“Carbon management on-farms is complex, there needs to be a multi-dimensional strategy which involves farmers, advisors, researchers and policy makers in order to achieve reduction targets. The time to act is now.”

Things have changed in the last 6 years. We see net zero commitments from global corporations pledging to source from regenerative farms; we have supply chains which are requiring environmental metrics alongside milk, and we have an emerging market for rewarding good practice that improves carbon sequestration. Carbon is no longer something which is a niche subject; gone are the days where carbon was the subject for squeezing in for the last 5 minutes at a conference, when delegates were tempted by the pull of the bar, there are now whole conferences dedicated to farm carbon management.

The fact that we are now discussing carbon more is brilliant. However, even for a self-confessed carbon geek like myself who is never happier than when talking about carbon, alongside the increasing attention, there also seems to be increasing confusion. Conflict often ensues between discussions around the potential for farming systems to be the problem or the solution, with the detail ignored in simple sound bites which are picked up by social media. Because the uncomfortable truth is that when we are dealing with carbon, the devil is in the detail. It is tricky to compare farming systems, as they are inherently all different, so the answer often becomes “it depends” rather than a confident and clear cut answer which can then be used for further discussions. Just because we are all now having to deal with carbon as an issue, doesn’t mean that we suddenly have a body of evidence to back up the potential impact of all of the mitigation measures that might be implemented. So there is a lag for research to catch up, especially around some of the holistic approaches where there are multiple variables. There are some things which we can all do which will help us understand where we are as a farm business and also think about potential options we have to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve sequestration on our farm.

Measuring the carbon performance of your farm

The old adage of “you can’t manage what you can’t measure” is certainly true of carbon accounting.

But when it comes to agriculture, measuring carbon isn’t as simple as it may first seem. Carbon accounting systems were designed to measure industrial processes; when measuring the emissions associated with a product manufactured in a factory, we are able quite simply to understand how the inputs lead to the outputs and it tends to all be neatly contained within a building. This is not the case when we use these metrics to measure farming systems. On-farm we are trying to measure biological systems, which are impacted by climate, soil type, topography and vegetation, as well as what we as farmers are doing in terms of our management. Which can make the whole thing a little tricky! However, undaunted by this complexity, carbon metrics are an essential tool which farmers can use to not just identify climate solutions, but also to baseline the farm’s emissions and drive technological change.

Identifying the carbon footprint of a farm business is the first vital step in being able to quantify the contribution that the farm is making to climate change. A carbon footprint calculation in its simplest form identifies the quantity and source of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide emitted from the farm (the emissions) and subtracts from the emissions the carbon that is being sequestered on-farm (sequestration) to provide your carbon balance. This balance is the starting point which should then highlight areas where improvements or changes can be made to reduce emissions and improve sequestration potential.

Reducing carbon emissions in a farming business makes sense on many levels. High carbon emissions tend to be linked to high use of resources, and / or wastage, so reducing emissions also tends to reduce costs. This makes the farm more efficient and should improve profitability. As well as the business opportunities that come from reducing emissions, farmers and landowners are in the unique position to be able to sequester carbon in trees, hedgerows and margins and within the soil.

Before being able to reduce emissions, you need to know where the emissions are coming from. Are the largest emissions coming from livestock, soils, fuels, or fertilisers? It is vital to get a picture of your business which is made possible by carbon footprinting.

There are various tools that you can use to provide the baseline carbon footprint of your farm. Tools include the Cool Farm Tool, AgreCalc, The Farm Carbon Calculator and Trinity. All of the tools use the same baseline information, but may provide a slightly different methodology which makes comparison between tools challenging. There are also tools designed specifically for use by farmers which are bespoke to that supply chain.

Although the simple principle of completing a carbon footprint assessment is the same, there remains variation between what scope and boundaries the tools use to calculate the results. This is good to understand before you start the process of doing a carbon footprint.

Boundaries are an important factor to consider (or understand with the tool that you are using) as it makes a difference on the data that you need to collect and also the results. Put simply, boundaries refer to where you are drawing the line around what is included in your calculation and what isn’t. For example, do you want to calculate the emissions associated with one farm enterprise or the whole farm, or just what is happening with the farm gate or further afield. Making sure this is clear before you start makes the whole process easier. This is also important if you are looking at getting to net zero – because if you are just footprinting one enterprise on-farm and only accounting for emissions, getting to net zero may be impossible.

It is also important to understand the scope of the calculations. For most supply chains, farmers are their scope 3 emissions, but on-farm there are also emissions to consider in those products that we use on the farm (for example fertiliser and feed).

Interpreting the results

So, once you have the results, deciding what to do is the interesting part. The results will be reflected as a carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e), but should also show you how that breaks down into the three gases (carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane). Key areas to focus on are the management of soils, fertilisers, manures, livestock, cropping, energy and fuel. There are also numerous opportunities to reduce emissions and costs, leading to improved resilience and profitability, as well as opportunities to improve carbon sequestration and soil health, the ultimate resilient business model! Absorbing more carbon than the farm emits is a goal that all farmers could work towards and understanding the farm’s current carbon position by footprinting is the first key step.

Sequestration – our unique asset

Improving soil carbon levels in farm soils is one of the most important projects that farmers and society can engage in. There is an undisputed link between enhanced soil carbon levels and increased agronomic productivity. Soils are more resilient and better structured; they support higher levels of biological activity and require less inputs to produce outputs. Including soil sequestration within calculators has been challenging in the past, models have only tended to focus on emissions which are more easily measured and tracked over time. During my Nuffield, I went to visit countries where farmers were being rewarded through carbon markets for improved sequestration, and learnt more about some of the challenges of measuring and managing soil carbon across farmed landscapes. Since World Soils Day 2022 we now have a UK Soil Carbon Code, which helps to align methods for measuring soil carbon sequestration. This is a great step forward which needs continued engagement to ensure that the methods are robust, practical and relevant.

Since 2017 we have been working on our Soil Carbon project, aimed at understanding how we can measure, manage and monitor soil carbon. It continues to be a brilliant project to work on, predominantly because of our incredible network of farmers who are showing what is possible, and continuing to innovate and prioritise soil health within their business. As well as digging thousands of holes for the project, looking at wider soil health metrics as well as carbon, we are now working to include the data within the carbon calculator, to provide a modelled assessment of carbon sequestration depending on farming practice and soil type.

Building soil health on-farm has so many benefits both for the individual farm business and for wider ecosystem and landscape function. There are many farmers who are doing brilliant things around sustainable soil management and by sharing knowledge and information, more can be achieved. By showcasing the positive actions farmers are taking, we can demonstrate the vast knowledge, adaptability and versatility of approach to soil management. Our farmer network continues to demonstrate their passion for soils and the benefits that maximising the quality and resilience of this biome can provide for their businesses.

Alongside soil, it is important to value our other sequestration source on-farm through how we manage our woodland, environmental areas and hedgerows. All of these contribute to our farm’s carbon account, and as such, it is important that these are considered in any calculations.

So what now?

We have made a huge amount of progress in the last six years since my Nuffield. Carbon is now mainstream. This is a positive step forward as we need to ensure that we all engage in a way which limits global temperature rise and helps halt climate breakdown. However, there still remain some challenges as carbon has become more familiar, which means that there is still more work to be done.

Carbon can still be viewed as something where agriculture is the main problem. As an industry we contribute around 11% of UK’s Greenhouse gas emissions, but 1.4% of UK carbon dioxide emissions. Farmers are already doing great things to reduce emissions which is a brilliant step forward. But it is important to remember that we can’t completely eliminate emissions associated with agriculture, we are never going to be a zero carbon industry. Providing positive examples and empowering farmers with the knowledge of what they can do along with the economic and environmental impacts of practices will help build knowledge around what is possible. Developing metrics that adequately take into account sequestration, and are not just based on emissions per tonne of output will also help to provide a more nuanced narrative which can help discussions with consumers. Focussing on soil health from a business resilience perspective will help to support soil function and bring emissions reductions as well as sequestration benefits.

As Carbon has risen up the agenda, FCT has also grown its team and I am immensely privileged to be joined by an incredible group of people who are supporting projects and farmers across the UK. This includes our Farm Net Zero project, aiming to showcase the opportunities farmers have to contribute to net zero within our industry as well as to other sectors. We are continuing to help inform and train the advisory sector (as well as the next generation of farmers) on how to manage carbon and greenhouse gas emissions and the opportunities that this brings. All of our projects and activities allow us to learn more from our farmer network (especially through Soil Farmer of the Year), who are continuing to innovate and pioneer new approaches.

Carbon may now be mainstream, but there is still so much to do to empower our farmers to understand how to manage carbon on farm, how to measure it, implement changes and align this with business objectives in a time of increasing uncertainty.

-

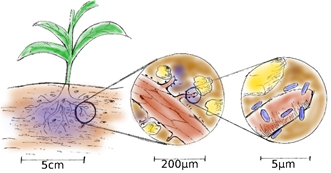

Potassium Solubilising Microbes

Steve Holloway puts the case for biology and foliar KSM – potassium solubilising microbes – for a more natural supply of phosphate and a way of reducing the fertiliser bill.

For a generation, farmers have taken their most valuable resource for granted, often considering it to be simple dirt. The focus has been on force-feeding the crop and beating the soil into submission. Driven by an ethos of yield over profit, with little respect for the aftermath, inputs for many farmers have typically increased since the 1940s. At that time fertiliser was seen as the easy solution to maximise crop returns, consequently the supply and demand situation was then able to keep pace and crop rotations became shorter to satisfy the ever-increasing markets. But all the while soil was still treated as an abused medium and consequently this once robust and resilient resource has suffered – until now. The farming solution has been to counteract this shortfall with greater chemical inputs. This counter-intuitive response has led to increased disease pressure, forcing perpetual reliance on agronomy to maintain healthy plants.

Stop: back up and look at what’s happening.

This is not a sustainable system and it will ultimately lead us down a path that we cannot come back from. You only need to look outside at the hedges and verges for inspiration. Their eco-systems are self-sustaining, resilient and productive; despite a lack of farm inputs, they have predominantly been left unassisted and have a naturally evolved durability.

A simple experiment you could try for yourself is to take a spade out to the centre of your field and compare the soil to what’s in your hedgerows. I guarantee the colour will be different, as will the smell. When you look at the soil texture, the hedgerow will be superior and you may also notice that there is a lot more life living in the more natural sample. This should tell you that things can, and should, be done in a better, more sustainable way!

A productive soil will naturally cycle nutrients, water and air whilst supporting both biological and crop life optimally, unfortunately, excessive inputs and soil disturbances tend to upset this already finely-tuned environment, – who are we to think that we know better?

There’s already a legitimate way that soils provide nutrition to their inhabitants, via biological exchange; subject to demand and conditions and complex reactions that both lock up and release elements within the soil’s profile. This trading of resources is often instigated by living organisms and is dependent on having healthy soil. When soil is degraded, natural resources are scarcer, leading to diminished bio-activity and, following this, less active soil will frequently require artificial intervention which in turn will throttle natural demand, thus perpetuating a more self-destructive cycle.

For example, since its conception, the Nutrient Management Guide (formally RB209), has advocated that farmers apply Potassium, subject to the estimated offtake of a crop and also the results given by a standard soil analysis. However, I would suggest that these guidance tables should also be considering the Total K assets that the soil has to offer and not just those measured by standard lab extraction, using a chemical solution. The Total K that is held by soil will be way above what’s measured conventionally.

I’m not suggesting that potash is bad for the soil, simply that things need to be more in balance, for the system to work effectively. Wouldn’t it be great to spend less on fertiliser and work with the soil as opposed to against it? After all, too much of anything can still be a bad thing. One solution would be, to utilise the soil’s capacity to cycle nutrients; or by supposedly satisfying a deficiency via chemical inputs, the natural ability of soil can be made redundant by switching off this valuable support mechanism.

Since time began, KSM (Potassium solubilising microbes) have been a part of the earth’s ecology; these microbial miners can break the connection that bonds potassium to other elements in the soil, thus making it more ‘available’ to a crop. Locked-up nutrition is so for a reason; once again too much of anything can be a bad thing, so communication is key between plant and microbe; that will instigate the necessary reciprocal exchange of elements beneficial to both parties. A generation of excess has created a deficiency of these bacterial benefactors, as a farmer – a conscientious farmer, the responsibility is yours to rectify this to benefit the grower, the soil and the crop.

It is possible with plant analysis to identify excesses and deficiencies, thus providing a valuable planning tool. There are multiple benefits to Potassium that include turgidity, health, quality and many others. Some are major, others minor, but frequently of equal importance. These KSM can be applied by a sprayer during the growing season, directly to the crop and soil, whereby they set about the task of freeing Potash for the crop to use; another added bonus is that with the increased microbial activity comes a more vibrant rhizosphere, which encourages better soil conditions and structure, leading to better quality air-water efficiency soil resilience, along with plant improved rooting.

Research has shown that KSM will actively support a crop’s demand for Potash. They produce organic acids and enzymes that help solubilise the fixed potassium into exchangeable form and make it assimilable by plants. They are activated on application and multiply by utilising the food source and or the exudates of the roots. Soil Fertility Services has developed one such product called Bio-K which contains a range of microbes specifically selected for their Potassium-releasing properties. Bio-K is earthworm-friendly, it can potentially replace around 25-30 % of chemical Inputs/ fertilisers and activates soil biologically, thereby increasing the natural fertility of the soil.

For the love of soil, please look back at what’s been done and learn from the lessons of the past, to build a better future.

-

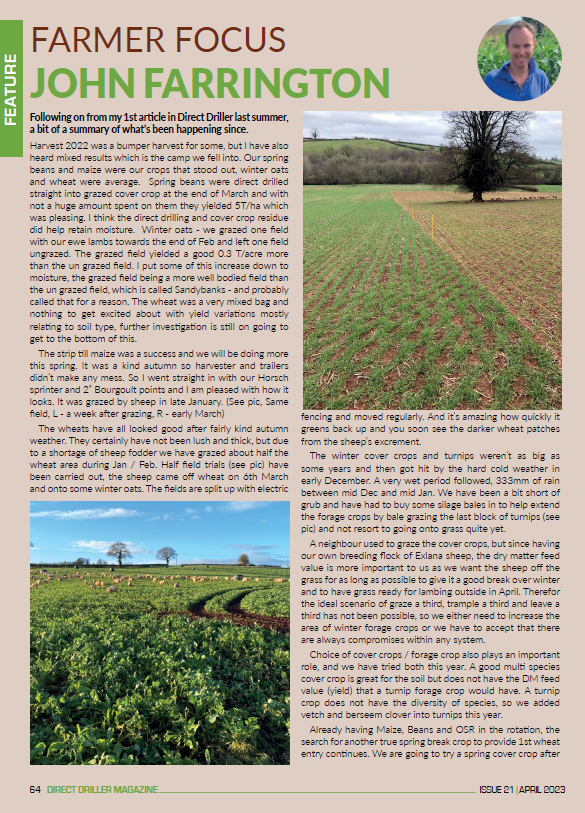

Farmer Focus – John Farrington

April 2023

Following on from my 1st article in Direct Driller last summer, a bit of a summary of what’s been happening since.

Harvest 2022 was a bumper harvest for some, but I have also heard mixed results which is the camp we fell into. Our spring beans and maize were our crops that stood out, winter oats and wheat were average. Spring beans were direct drilled straight into grazed cover crop at the end of March and with not a huge amount spent on them they yielded 5T/ha which was pleasing. I think the direct drilling and cover crop residue did help retain moisture. Winter oats – we grazed one field with our ewe lambs towards the end of Feb and left one field un grazed. The grazed field yielded a good 0.3 T/acre more than the un grazed field. I put some of this increase down to moisture, the grazed field being a more well bodied field than the un grazed field, which is called Sandybanks – and probably called that for a reason. The wheat was a very mixed bag and nothing to get excited about with yield variations mostly relating to soil type, further investigation is still on going to get to the bottom of this.

The strip till maize was a success and we will be doing more this spring. It was a kind autumn so harvester and trailers didn’t make any mess. So I went straight in with our Horsch sprinter and 2” Bourgoult points and I am pleased with how it looks. It was grazed by sheep in late January. (See pic, Same field, L – a week after grazing, R – early March)

The wheats have all looked good after fairly kind autumn weather. They certainly have not been lush and thick, but due to a shortage of sheep fodder we have grazed about half the wheat area during Jan / Feb. Half field trials (see pic) have been carried out, the sheep came off wheat on 6th March and onto some winter oats. The fields are split up with electric fencing and moved regularly. And it’s amazing how quickly it greens back up and you soon see the darker wheat patches from the sheep’s excrement.

The winter cover crops and turnips weren’t as big as some years and then got hit by the hard cold weather in early December. A very wet period followed, 333mm of rain between mid Dec and mid Jan. We have been a bit short of grub and have had to buy some silage bales in to help extend the forage crops by bale grazing the last block of turnips (see pic) and not resort to going onto grass quite yet.

A neighbour used to graze the cover crops, but since having our own breeding flock of Exlana sheep, the dry matter feed value is more important to us as we want the sheep off the grass for as long as possible to give it a good break over winter and to have grass ready for lambing outside in April. Therefor the ideal scenario of graze a third, trample a third and leave a third has not been possible, so we either need to increase the area of winter forage crops or we have to accept that there are always compromises within any system.

Choice of cover crops / forage crop also plays an important role, and we have tried both this year. A good multi species cover crop is great for the soil but does not have the DM feed value (yield) that a turnip forage crop would have. A turnip crop does not have the diversity of species, so we added vetch and berseem clover into turnips this year.

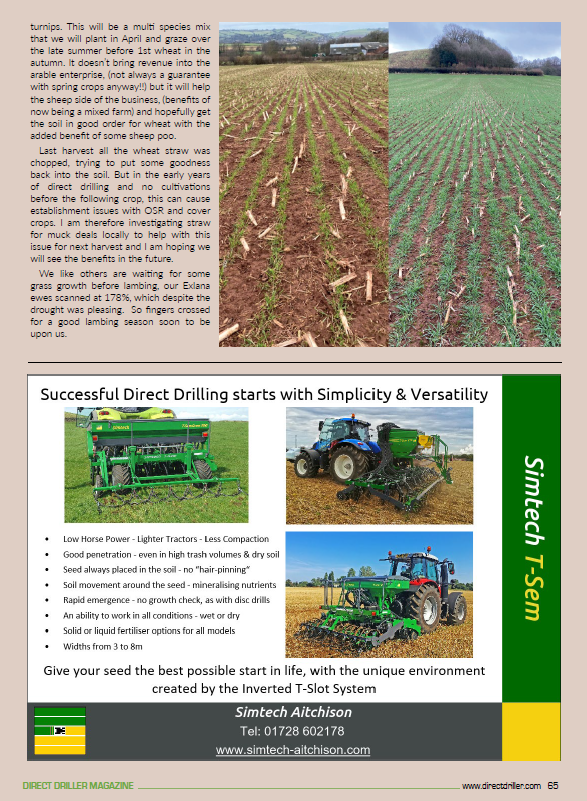

Already having Maize, Beans and OSR in the rotation, the search for another true spring break crop to provide 1st wheat entry continues. We are going to try a spring cover crop after turnips. This will be a multi species mix that we will plant in April and graze over the late summer before 1st wheat in the autumn. It doesn’t bring revenue into the arable enterprise, (not always a guarantee with spring crops anyway!!) but it will help the sheep side of the business, (benefits of now being a mixed farm) and hopefully get the soil in good order for wheat with the added benefit of some sheep poo.

Last harvest all the wheat straw was chopped, trying to put some goodness back into the soil. But in the early years of direct drilling and no cultivations before the following crop, this can cause establishment issues with OSR and cover crops. I am therefore investigating straw for muck deals locally to help with this issue for next harvest and I am hoping we will see the benefits in the future.

We like others are waiting for some grass growth before lambing, our Exlana ewes scanned at 178%, which despite the drought was pleasing. So fingers crossed for a good lambing season soon to be upon us.

-

Soil Health Knowledge on The Farming Forum

About a year ago a whole new side of TFF was born – we called is Resources. The main part of the site, is know by most for it’s farmer-to-farmer content, but the new section was designed specifically for formal knowledge. Papers, trials, articles published from the wider industry to give farmers the formal and conversation on a topic in the same place. Nearly 2000 pieces of knowledge (283 hours of reading) have been added in this time and we have created a number of sections, to help you find more interesting content or for you to subscribe to. It is becoming a fantastic place to read the detail about what is new in terms of research in the farming industry. In the past year this content has accessed over 1 million times.

We will cover a couple of sections here:

Regenerative Agriculture – https://thefarmingforum.co.uk/index.php?resources/categories/21/

Stats: 220 Resources – 31 hours of reading

The section on Regenerative Agriculture on The Farming Forum provides a section for farmers and experts to explain and exchange ideas on sustainable farming practices that can improve soil health, biodiversity, and farm profitability. The discussions cover a range of topics, including soil regeneration, crop rotation, agroforestry, cover crops, regenerative grazing, and sustainable livestock management. Contributors share their experiences, insights, and best practices, as well as the challenges they face in implementing regenerative agriculture techniques. The section aims to encourage farmers to adopt more sustainable farming practices and to foster a community of like-minded individuals who share a passion for sustainable agriculture.

Soil Health – https://thefarmingforum.co.uk/index.php?resources/categories/soil-science.22/ –

Stats: 113 Resources – 16 hours of reading

The section dedicated to “Soil Science” contains various resources related to soil management and agriculture. It includes articles, discussions, and papers on topics such as soil fertility, soil health, soil testing, soil conservation, and soil amendments. The section also covers different types of soils and their characteristics, as well as techniques and tools for soil analysis and improvement. The resources are contributed by academics, farmers, agricultural experts, and soil scientists, providing a diverse range of perspectives and insights on soil science and its practical applications in farming.

Carbon – https://thefarmingforum.co.uk/index.php?resources/categories/15/

Stats: 139 Resources – 14 hours of reading

The section on carbon on The Farming Forum website explains the concept of carbon farming and its potential benefits for farmers. Carbon farming involves implementing sustainable land management practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and sequester carbon in the soil and vegetation. By doing so, farmers can generate carbon credits, which can be sold to companies or governments that need to offset their carbon emissions. The section provides information on different carbon farming practices, such as cover cropping, reduced tillage, and agroforestry, and explains how to calculate carbon sequestration and estimate the value of carbon credits. It also includes case studies of farmers who have successfully implemented carbon farming practices and generated additional income through carbon credit sales.

Why we created Resources on TFF?

We know how valuable farmer to farmer recommendations are when it comes to making decisions on farm. It’s why the Farmer Focus pieces in this magazine are deemed as the most useful by our readers. However, it is always useful to get multiple views on any subject. When you can back up farmer anecdotal evidence with trials and research data, then the argument for change becomes overwhelming. We wanted to create a situation where we could present both sides of any argument in one place. We aren’t there yet, but the addition of Resources on TFF is a major step to getting there.

-

Horsch: The fine art of direct seeding

With regard to plant production drought and heat are limiting factors. As a result of the climate change extreme weather situations occur more and more frequently. To avoid negative consequences on the yields, methods like direct seeding are used.

Michael Horsch

Michael Horsch’s opinion with regard to direct seeding is clear: “Those who practice direct seeding as a religion forego profit and in the worst case can ruin their farms. We at HORSCH have been dealing with direct seeding for 40 years. With all ups and downs.” With regard to direct seeding there are quite a few things to consider. “In the first step direct seeding is not a question of technology. What is crucial is a good soil structure, a balanced rotation, a good soil covering and the sowing time.”

In Europe, direct seeding was mainly used as an argument for building up humus in the recent past. A mix of abandonment of tillage and catch crop cultivation can increase the share of organic substance in the soil. If you take a closer look at direct seeding all over the world, you will find the most different motivations for direct seeding: in the dry regions the focus is clearly on saving water. In the hot, partly subtropical regions the soil has to be covered so that the soil temperature does not rise into a range that is detrimental to the plant. The high-precipitation areas particularly need direct seeding and a soil cover to prevent erosion. And let’s not forget the markets with very low yields: Saving costs by sowing directly is another argument.Direct seeding as a water-saving sowing method

Because of climate changes and the more extreme heat waves (35-40 %) of the past years which some farmers still worry about, farmers more and more think about the topic direct seeding and water-saving cultivation. The problem particularly affects for example parts of Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. Why could direct seeding be a solution (at least partly)?

“Let’s take the above mentioned countries as an example. Maize, winter wheat, winter rape and sunflowers are the main crops. After rape/sunflower, when it still is very dry in September and October, sowing wheat with the Avatar after an ultra-shallow pass with the Cultro would be appropriate. After maize, too, you normally can quite well sow wheat with a single disc seed drill. Unless there is too much straw on the field. In this case you first have to incorporate the straw a little bit, for example with a disc harrow. If you want to sow maize in spring – this is done for example in Brazil, you have to decide from case to case. For if the soil temperature remains too low, it is a risk!”

The knife roller Cultro can actively stop a catch crop from growing.

A covered soil

Dark cultivated fields do not reflect solar radiation as well as uncultivated or covered fields. They absorb the sunrays and warm up faster. This, of course, depends on the type of soil. Thus, for example dark brown, almost black soils warm up considerably faster than light or even slightly red soils. “We assume that a soil cover consisting of plant residues improves soil protection. For it reduces evaporation, increases the water-holding capacity and reduces erosion.”

This is also advantageous for germination and root development, i.e. a crop can develop better if the soils do not tend to be overheated. “Especially in spring, there can be a fine line. For there are regions where in this case the soil does not reach the minimum temperature. What is good on the one hand can also be a disadvantage on the other hand if the soil does not warm up sufficiently.” If it is too hot in the soil, a safe germination and root development of the plant is no longer possible. Once the minimum temperature has been reached, the plant stops growing. If the temperature even is exceeded too such an extent that protein degenerates, plant development is completely finished. In some regions that have to struggle with extreme heat, this is a big challenge.

Another advantage of a soil cover is that it keeps the humidity that is transported to the surface in the upper layer of the soil. Thus, a kind of micro-climate is created where residual humidity accumulates in the topsoil and guarantees a good emergence. “You only have to go barefoot through a wheat population without any residues on the surface in June or July. Even if the population is dense, you burn your feet on the black clay soil – although the soil is covered with growing plants. This shows that there is a connection and that a population keeps up longer if there are residues on the surface.

According to Michael Horsch, we will have to give very much attention to the topic stubbles and stubble lengths to find an optimum way.

Another problem I noticed: if the straw stubbles are too long resp. if the straw remains on the field too long, among others mice feel very comfortable. I saw this only recently in Romania. The rape population did not look too bad but in the field, there was one mousehole beside the other! The same is true for slugs. If there is too long straw and too high humidity for a long period of time, the slugs devour the rape, wheat etc.”

Catch crop cultivation and direct seeding

Cultivating a catch crop before sowing directly is always better. But a prerequisite is that the catch crops fit in and that a sufficient water supply is guaranteed.

Catch crops can help to increase the humus content. Moreover, another rotation member always can separate the previous crop from the next crop phytosanitary. “In conventional farming this separation is done by tillage.”

If the total precipitations are low, farmers, of course, discuss the question if catch crops do not additionally require water. “It is obvious that this simply is not possible in some regions. For if it does not rain during the cultivation break in summer, the catch crops don’t grow either and, thus, it does not make sense to cultivate them.”

How can you actively stop the growth of a catch crop? This can either be done by frost, knife rollers or the use of glyphosate. “In this case, you have to check which method makes sense in which region. For in Europe, the use of glyphosate will soon no longer be an option. You then need other measures to stop the growth.”

Another question that always is asked when talking about direct seeding is if direct seeding and tillage are inconsistent. Not at all – quite the contrary. “I my opinion, a combination of both might even be the key for the future. The reasons are various. On the one hand, we see that direct seeding only involves high yields if the soil structure is very good. As I already mentioned, a good soil structure can be achieved resp. encouraged by growing catch crops. But there also are situations where there is no time to improve the soil with catch crops. In this case, it, of course, makes sense to loosen the soil so that the roots can grow deeply and reach water in the subsoil.

We notice that even in countries like for example Brazil where direct seeding has already been established for years the soil is loosened deeper at 30 – 40 cm as the soil, despite the catch crop, is compacted.“

But what direction will the topic direct seeding in Europe take? Does direct seeding have a future here? “We have to act on the assumption that weather extremes will increase and that we will get more hot, dry years. I don’t think that we will see a pure direct seeding, i.e. without any tillage, in our clime. In my opinion, farms will have to prepare in such a way that they prepare their soils to be able to sow directly in dry years if required. This means: always perfect straw distribution, cereals stubbles as short as possible, avoid resp. considerably reduce compaction/tracks during the harvest (e.g. by CTF harvest).”

Due to its individually controlled disc coulter SingleDisc, the Avatar 12.25 SD can be adapted to different sowing conditions and thus is also ideal for direct seeding.

This was about the general use of direct seeding. In the next terraHORSCH we will explain in detail which sowing method (discs, tines) fits where, how it is to be used, which preparatory work, if required, is suitable.

Moreover, we will provide tips with regard to the C:N ratio of residues, stubble lengths and how to handle them.

The angles of the closing wheel can be adjusted depending on the soil conditions. For direct seeding or on very heavy soils they can for example be set aggressively.

-

UK’s first Agroforestry Show to explore the perks of farming with trees

Hundreds of farmers and foresters can discover the benefits of farming with trees for sustainable food production in the UK’s first Agroforestry Show.The event, hosted by the Woodland Trust and Soil Association and sponsored by lead partner Sainsbury’s, will explore the boost that trees can deliver for nature and climate as well as delivering resilience and productivity for farm businesses.

It will bring together a thousand guests spanning across farmers, foresters, tree nurseries, growers, graziers, advisors, funders, food businesses, policy makers and agroforesters.

Tickets are now on sale for the two-day gathering, on Wednesday 6 and Thursday 7 September, which will include:

● Knowledge exchange workshops and inspiring talks

● Farmer and forester led discussions

● Agroforestry field walks

● Live equipment demonstrations

● Exhibitions and market stalls

Soil Association Chief Executive Helen Browning will be hosting the event at Eastbrook Farm, in Wiltshire, where she runs a mixed farm with an agroforestry project that has been running for seven years.

She said: “We are delighted to be working with the Woodland Trust to host the UK’s first ever Agroforestry Show. Agroforestry holds so many of the answers to the climate and nature crises, and it has also been proven to boost farm productivity. Trees improve soil health, provide habitats for wildlife including beneficial insects, give shelter and forage to livestock, and cut carbon emissions. And they do all this while providing additional funding streams through fruit, nuts and timber. Much more than a trade show, this two-day gathering will inspire hundreds of land stewards to collaborate and get involved with agroforestry.”

Agroforestry offers huge opportunities to the forestry sector and this show will be a catalyst to strengthen the relationships between the forestry and farming sectors. Working together the two sectors can identify solutions to help overcome the current knowledge and financial barriers to widescale up take of agroforestry.

The Woodland Trust has a decade of experience in supporting agroforestry and at the show they will highlight how we support landowners and farmers to adopt agroforestry on their land, via a range of subsidised tree offers and expert advice. The trust aims to tap into the demand from farmers wanting to do more for the environment and help to unlock this potential with this event.

Helen Chesshire, Lead Farming Advocate at the Woodland Trust said:

“Having many more trees within our farmed landscapes could bring so much good. Trees make an important contribution to tackling climate change and helping reverse biodiversity declines. Agroforestry supports farm businesses to adapt to climate change and become more resilient to the types of financial, social and environmental shocks that are likely to be a part of the future.

“This event is about making trees work for farm businesses and the local environment that they operate within and rely on. It is a sign of hope that there are solutions to grasp – if we take them. We will highlight this and more at September’s show.”

The event, also sponsored by the Forestry Commission, Defra, Tillhill, Farm Carbon Toolkit and Royal Forestry Society, comes hot on the heels of a ground-breaking report, funded by the Woodland Trust, which showed how a major increase in agroforestry – farming with trees – in England, is essential if the country is to meet nature and climate targets, whilst at the same time securing long term food production.

The report was developed from new analysis commissioned from Cranfield University which revealed arable farms that integrate trees within arable crops – known as silvoarable systems – could lock up eight tonnes of CO2 per hectare per year over 30 years. Eight tonnes of CO2 is equivalent to the annual emissions of an UK citizen.

Buy your tickets now (https://www.agroforestryshow.com/tickets)

Two-day tickets are offered on a tiered ticket scale to make this event as accessible and affordable as possible. Single day tickets will become available when the event program is launched. Early bird tickets are available now but will go fast.

A limited number of bursary funded places are also available for those who require additional support to attend the event. Get in touch for more information at: info@agroforestryshow.com

-

Agronomist Focus – Dick Neale

Healthy soil … what does that actually mean?

Written by Dick Neale from Hutchinsons

Hutchinsons launched its Healthy Soils Assessment service in 2016. Since then the overall understanding of what goes into making a soil healthy has increased massively.

Shared knowledge, research, observation, plus a clear increase in grower interest have all combined to accelerate the learnings and engagement across the industry.

Everyone now appreciates that soil is a living, breathing entity and that microbiology and increasing microbial biomass is as important an objective as increasing organic matter.

Our Healthy Soils Assessment, Gold Soil test and now the combination of these with TerraMap soil mapping in TerraMap Gold, are vital components in creating a starting point of information with which to make clear decisions on what future interventions may be needed, be they physical, chemical or biological.

Over the past seven years we have identified some clear common denominators with regards to soil health

- The seeding zone of seedbeds tends to be overworked

- Overworking leaves seedbeds at risk from slaking during heavy rain events

- Slaking or capping of the seedbed creates anaerobic conditions in the seeded zone and severely impairs crop establishment

- Poor infiltration of surface rainfall due to capping is incorrectly identified as poor drainage and addressed via deeper tillage passes.

Modern tillage machinery can create good seedbeds quickly, but problem grassweeds such as black grass or ryegrass require delayed drilling to be practised for good cultural control.

The two elements of delayed drilling and early creation of finely worked seedbeds are rarely compatible, frequently leading to capped and anaerobic seedbeds.

The assessment of baseline issues and the farming requirements like grassweed control allows us to work with customers in addressing all issues beyond just having a focus on healthy soil or just achieving good weed control, a plan allows all elements to be positively impacted at the same time.

Soil structure and the soil’s own innate ability to maintain a resilient structure is a combination of factors, but understanding that soil moving implements never create good soil structure is a major shift in understanding.

Good soil structure is created via natural processes, the building of aggregates by microbiology, binding of these together via growing roots and creation of burrows by worms, all together creating stable resilient soil, with good gas exchange, water movement and storage.

Soil moving implements change this structure, and always in a negative way for the long term. However, farming soil damages soil and cultivation interventions are frequently needed to address problems such as compaction at depth, or shallow compaction.

Assessment of compaction depth is a vital component in good soil management – shallow compaction is not addressed appropriately by deep tillage. In all cases tillage can be used and frequently should be used, to remove a structural problem where identified, but tillage does not create good soil structure – natural processes do that. Tillage only improves or removes a structural problem in the short term, long term the issue will return if other interventions are not used in combination.

Deep tillage breaks up natural soil structures and produces a ‘soft’ loose structure which is easily recompacted via the passage of heavy machines during the farming year. The recompacted soil is again deep tilled to alleviate the compaction facilitated by the original deep tillage. We have to break the cycle, but doing that successfully again requires a plan centred on an assessed baseline for your farm, a plan that transitions to an agreed approach, a plan that anticipates both the positives and potential negatives of the transition period, a long term plan that incorporates all the elements for resilient and healthy soil.

Vital Elements:

- Soil assessment

- Gold test

- Utilisation of cover and catch crops

- Appropriate cultivation when required

- Understanding of chemical, biological and physical impacts on soil structure

- Initiating processes to cycle nutrients within the soil

- Never lose focus of growing strong and healthy cash crops.

-

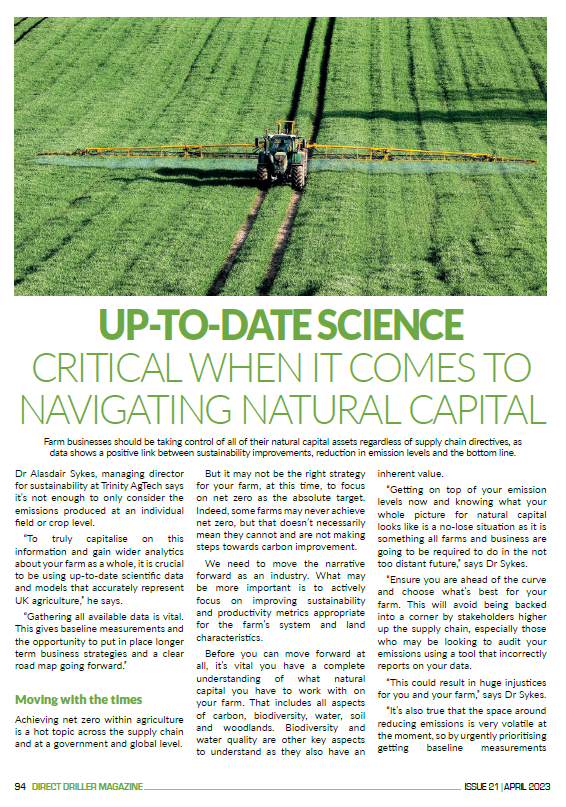

Up-to-date science critical when it comes to navigating natural capital

Farm businesses should be taking control of all of their natural capital assets regardless of supply chain directives, as data shows a positive link between sustainability improvements, reduction in emission levels and the bottom line.

Dr Alasdair Sykes, managing director for sustainability at Trinity AgTech says it’s not enough to only consider the emissions produced at an individual field or crop level.

“To truly capitalise on this information and gain wider analytics about your farm as a whole, it is crucial to be using up-to-date scientific data and models that accurately represent UK agriculture,” he says.

“Gathering all available data is vital. This gives baseline measurements and the opportunity to put in place longer term business strategies and a clear road map going forward.”

Moving with the times

Achieving net zero within agriculture is a hot topic across the supply chain and at a government and global level.

But it may not be the right strategy for your farm, at this time, to focus on net zero as the absolute target. Indeed, some farms may never achieve net zero, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they cannot and are not making steps towards carbon improvement.

We need to move the narrative forward as an industry. What may be more important is to actively focus on improving sustainability and productivity metrics appropriate for the farm’s system and land characteristics.

Before you can move forward at all, it’s vital you have a complete understanding of what natural capital you have to work with on your farm. That includes all aspects of carbon, biodiversity, water, soil and woodlands. Biodiversity and water quality are other key aspects to understand as they also have an inherent value.

“Getting on top of your emission levels now and knowing what your whole picture for natural capital looks like is a no-lose situation as it is something all farms and business are going to be required to do in the not too distant future,” says Dr Sykes.