If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

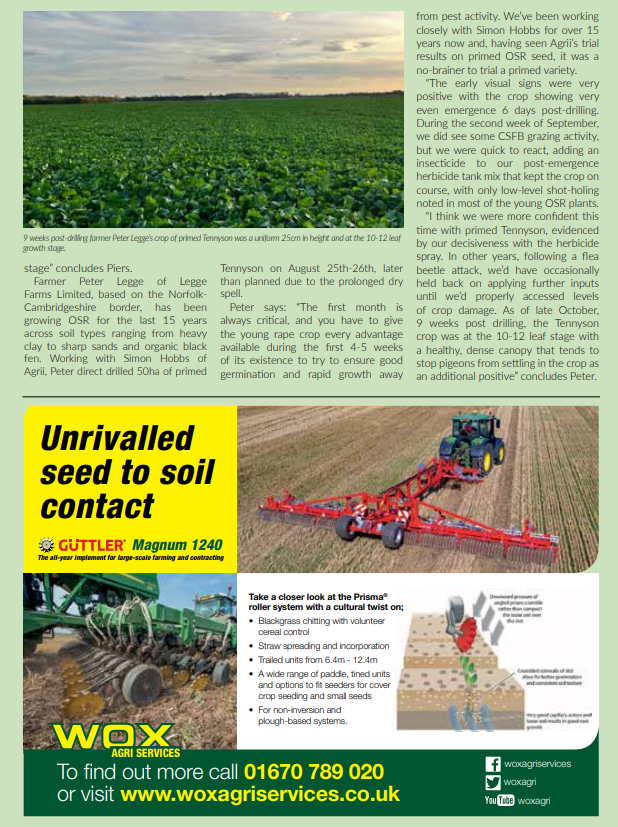

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

De-risking OSR establishment

Farmers are reporting positive benefits of drilling primed seed

Despite 37 years’ industry experience, Agrii agronomist David Vine readily admits that growing oilseed rape successfully year-in, year-out can still be a huge gamble for many growers with significant challenges posed by slugs, pigeons, cabbage stem flea beetle (CSFB) and, given this year’s weather, the often-difficult task of finding adequate soil moisture.

David says: “It’s still a lottery and, over the last 37 years, I’d argue that it has become even more difficult, with serious blackgrass resistance and the neonicotinoid ban to add to that list of challenges.

“However, there are new ways in which rape growers can stack the odds in their favour. The advent of priming technology into oilseed rape in the last two years has made a difference. It’s a proven technology that increases early plant vigour, offers more even crop germination and, given that there are no chemicals involved, it’s a sustainable and environmentally friendly process” he adds.

Working with farming business A & E Beckett, based near Birmingham, David recommended a trial on 21ha of primed Tennyson, the only primed hybrid OSR variety available in the UK. Direct drilled for minimum soil disturbance on August 12th, at a rate of 50 seeds per M2 along with two unprimed varieties, David confirms that the early results have been extremely promising.

“We drilled the primed Tennyson in fields that had been left fallow for one year, but despite this unusual scenario, combined with only 30mm of rain in the first 3 weeks post-drilling, the crop came through with great uniformity and continued to grow well despite the combined attention of CSFB and significant pigeon populations. By the 3-4 leaf stage the Tennyson still looked healthy with only small shot-holing on the leaves from the CSFB grazing.

“Unfortunately, the two unprimed varieties suffered heavy attacks from flea beetle on August 24th and 25th and we were forced to spray some growth stimulants to help them. However, the primed Tennyson crop didn’t require a spray due to its advanced early growth stage.

The dense canopy and even crop coverage of primed Tennyson discourages pigeons from settling in the crop Beyond the priming technology, Tennyson is an impressively resilient variety with a strong disease profile. Its verticillium resistance trait could also be a major positive on farms with tight rotations and I will be following its progress closely” he concludes.

Based on the Lambourn Downs, between Wantage and Lambourn in Oxfordshire, farm manager Piers Cowling of Sparsholt Manor Farms direct drilled 62ha of primed Tennyson at 40 seeds per M2 on Sept 3rd, having achieved 3.45t/ha on a 50ha crop of unprimed Tennyson earlier this year.

Piers says: “With no rain in August we were forced to drill later this time, although there was a lot of confidence behind Tennyson, given we knew it had displayed significant early vigour last year.

“Of the rape varieties we selected, Tennyson was the last to be drilled but – despite the staggered starts, all 3 varieties emerged together during the week commencing September 11th, with the Tennyson crop the most uniform of the 3. With the benefit of some much-needed October rain all our rape is progressing well, successfully overcoming some CSFB grazing at the expanded cotyledon stage” concludes Piers.

Farmer Peter Legge of Legge Farms Limited, based on the Norfolk-Cambridgeshire border, has been growing OSR for the last 15 years across soil types ranging from heavy clay to sharp sands and organic black fen. Working with Simon Hobbs of Agrii, Peter direct drilled 50ha of primed Tennyson on August 25th-26th, later than planned due to the prolonged dry spell.

Peter says: “The first month is always critical, and you have to give the young rape crop every advantage available during the first 4-5 weeks of its existence to try to ensure good germination and rapid growth away from pest activity. We’ve been working closely with Simon Hobbs for over 15 years now and, having seen Agrii’s trial results on primed OSR seed, it was a no-brainer to trial a primed variety.

Farm Manager Piers Cowling achieved 3.45t/ha with a crop of unprimed Tennyson this summer and is now growing primed Tennyson for the first time “The early visual signs were very positive with the crop showing very even emergence 6 days post-drilling. During the second week of September, we did see some CSFB grazing activity, but we were quick to react, adding an insecticide to our post-emergence herbicide tank mix that kept the crop on course, with only low-level shot-holing noted in most of the young OSR plants.

“I think we were more confident this time with primed Tennyson, evidenced by our decisiveness with the herbicide spray. In other years, following a flea beetle attack, we’d have occasionally held back on applying further inputs until we’d properly accessed levels of crop damage. As of late October, 9 weeks post drilling, the Tennyson crop was at the 10-12 leaf stage with a healthy, dense canopy that tends to stop pigeons from settling in the crop as an additional positive” concludes Peter.

9 weeks post-drilling farmer Peter Legge’s crop of primed Tennyson was a uniform 25cm in height and at the 10-12 leaf growth stage.

-

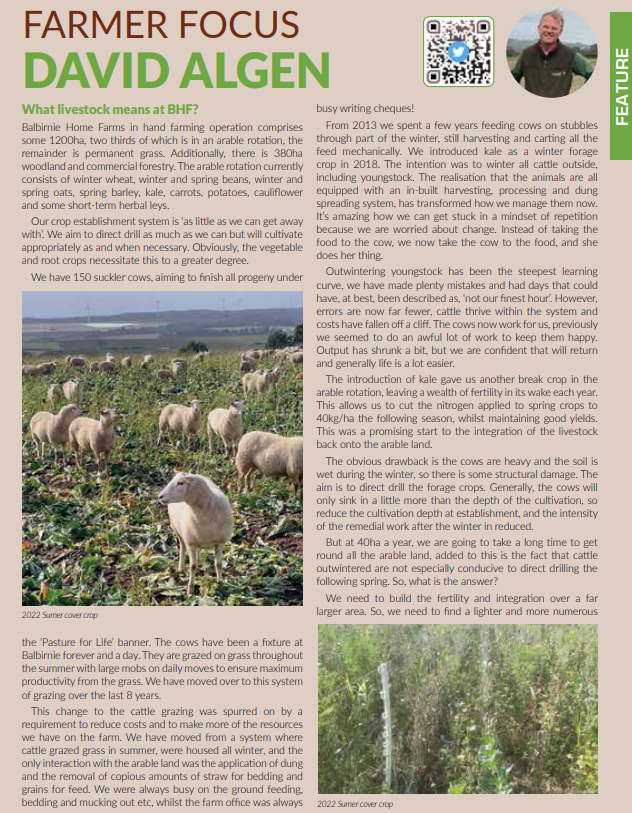

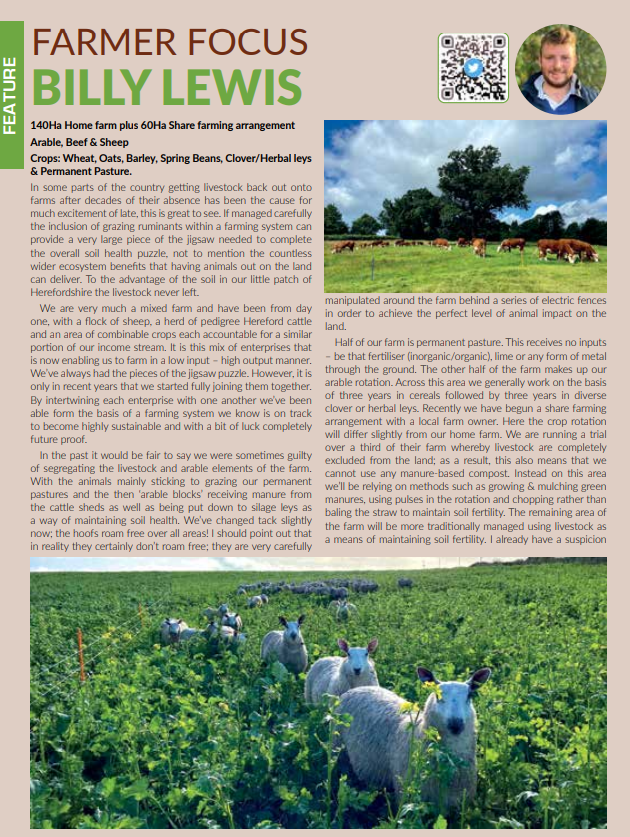

Farmer Focus – Ben Martin

January 2023

Well, the last few weeks have been exciting! A few weeks back I finished a 7yr stint managing a large veg and cereal operation in West Suffolk and am now taking a bit of time off to explore what direction I want to take myself and my little family next. Taking a bit of time out has come at a great time for me personally, we have come through yet another season of intense pressure to get crops to harvest (thanks mainly to that wonderful draught we had) and I need this time to decompress, to see what is out there (potentially outside that farm management bubble) and to start the new year in a rejuvenated mindset. Oh, and I turn 40yrs old shortly – talk about a midlife re-evaluation!!

So, how did I arrive at this point? Before I come to that, a quick intro. I’m Ben, I live in a glorious part of West Suffolk, with my amazingly supportive wife Emma, our beautiful little girl Maeve and our spaniels. I love spending as much time with them all as possible, but I enjoy my own company as well – out walking and exploring, cooking and watching the mighty Ipswich Town Football Club.

Farming is all I have ever known really, I don’t come from a farming family as such, but Dad and Grandad worked for the local farmer for most of their careers. We lived in a tied farm cottage on one of the farms, it was just the best environment to grow up in. We were lucky enough to been bought up around plenty of animals, sheep, pigs, chickens, and goats were all family pets during our childhoods. My teenage summers were spent working for a neighbouring farming family, they gave me the most wonderful start to farming and instilled into me early on, how to work hard, attention to detail and how to look after people (the best harvest teas ever!!).

An Agricultural degree from Writtle College came next and like most old Agri students will say, that was the best 3 years ever! Learning a lot, socialising A LOT and making the best friends. Friends that are still very much part of my life 20yrs later. I spent the rest of my twenties gaining so much real-life experience of farms. Working on remote sheep farms in the darkest depths of mid Wales, silage seasons in Yorkshire and big arable farms in East Anglia. I loved them seasoning rolls, traveling around and meeting some great people.

The backend of my twenties I met my now wife Emma, another Young Farmers success story! During that time I was really enjoying things, as everyone should in their late 20s. I was working with a really kind and supportive farmer, where I was able to use spare bits of his farm to establish a firewood business and rear rare breed pigs in his woodlands. It was a great time, hard work but so rewarding. I was also lucky enough to secure a 6yr FBT of my own, on 32ha of arable land, what an eye opener that was – growing and financing my own crops. An experience not many farm managers can say they have had and one that I learnt so much from. It was during this time that I had my first real exposure to cover crops and direct drilling. I established a basic mustard cover crop on my land in front of potatoes and using a Claydon Drill with the chap I was working for.

In my 30th year, after much saving, my wife and I had a once in a lifetime trip to New Zealand. We travelled the South Island in a camper and had the time of our lives. With no real time pressures etc, we just plotted a big loop around the Island and spent the next 4 weeks in our camper cruising around exploring the amazing South Island. An unbelievable experience, as everyone says who has been to NZ, but also an experience where I had time to reflect on things and concluded that as much as I had enjoyed my late 20s, I wasn’t going to have the structure or security by carrying on, to support a family in the future. So, when we got back, I had a final year doing what I had been before we went and then decided to try and carve out a career in farm management.

The next 7yrs was spent as assistant, then manager, on a 1300ha veg and cereal business. A massive opportunity and one where I learnt a huge amount. A complex operation, with high value crops, irrigation, several full-time staff, draught prone light sandy soils and working with various landowners. During my time there I had support and a real driving passion to try my hardest to repair and improve the soils on the farms involved, without removing the veg crops from the rotation. Not an easy task – but one that I was not alone in tackling. Taking things cautiously and steady, I started with 10ha of over winter cover crops in my first year to cover cropping all land in front of spring crops in my last couple of seasons (400ha) and integrating livestock into the system by having sheep on farm to over winter on these cover crops. The farm staff bought into my vision, that was very important. Cover crops were a vital tool to helping the soils improve, as was working the light soils a lot less and only cultivating deep where absolutely necessary. Companion crops were grown alongside OSR crops, catch crops between early lifted veg and following cereal crops and a 4ha regenerative potato trial grown alongside a very supportive processor. Introducing a 1 pass drilling system, using a new low disturbance subsoiler tool bar and the existing drill (Horsch Pronto) hooked on the back, was a real success. Financially, there was a huge reduction in establishment costs but also a much-improved timeliness of the operation as it cut out 2 cultivation passes.

I was fortunate in being able to bring inspiring and highly experienced people on the farm, such as Ian Robert and Ben Taylor Davis, to help us along with what we were trying to do. Getting the whole team around a soil pit on the farm, with Ian stood in the bottom of it was one of the best spent days we all had as a collective!

However, things move on and as a lot of people have told me recently – a change is as good as a rest!

So, what now…?

This is where it gets exciting!

Since posting on Twitter that I was moving on and looking into future opportunities, I have had several conversations with people about future roles and direction. Areas of agriculture I hadn’t really considered historically but ones that now look attractive. I am approaching all of this with a very open mind – you have too, that farm management bubble I had been in for several years does seem to prevent you at times to see the bigger, industry wide picture.

I am focused on an environmentally sensitive farming approach; I would certainly be keen to stay in farm management and work with a landowner who is of a similar mindset. I have known great people like Adam Driver and John Pawsey for along time now, they are good friends, I have worked for them both and in my opinion, they epitomise how large farms can work closer with the environment, albeit using 2 differing approaches to farming their land.

My short-term aim is to get out and about, meeting and chatting with as many people around the UK as possible. People that will lend me an hour or 2 of their time, just to chat and have a wonder around their businesses maybe. Not just chatting farming, but life, business and general stuff too. I have got recruiters lined up to chat with, companies to chat with who have approached me, but I want to speak with individuals as well.

As I said earlier, I am open to all discussions going forward. I know I have a lot to offer, its just finding that opportunity that fits right for me and my family going forward. Please do drop me a message if you would like to have a natter and have an hour spare! So, for now, I am going to enjoy some quality time off with my beautiful girls. And some long dog walks!

Twitter – @bencm305

Email – bencmartin@hotmail.co.uk

-

Nitrogen Stabilisers (part 2): Carbon Inputs

Joel Williams, Integrated Soils

In part 1 of this article, we highlighted that both urease and nitrification inhibitors have a minor impact on soil biology but there remains some concern over the negative impact of urease inhibitors on the plants ability to take up and metabolise the urea form of nitrogen [N] – a favourable and efficient form of N for plant growth. Outside of these phytotoxicity concerns, synthetic inhibitors also have other drawbacks, including difficulties in application, cost, degradation, pollution and entry into the food system1,2. Beyond these chemical inhibitors, there are other compounds of interest that can bring similar benefits – naturally occurring, biological inhibitors and carbon-based compounds that can stabilise N inputs and slow the conversion of N to reactive and unstable forms.

Biological Inhibitors

We will discuss below the potential of humic substances to bind to and stabilise N inputs however they have also demonstrated both urease and nitrification inhibitory properties3–6, no doubt part of their modes of action. Additionally, a range of plant compounds (plant/tissue extracts) have also been identified – generally discussed in the context of decaying residues of cash or cover crops – but also, plant extracts such as garlic or aloe vera have demonstrated urease inhibition properties. All this said, it is plant root exudates that are currently a noteworthy emerging area of research into identifying novel biological nitrification inhibitors1,2. A potential pool of hundreds of compounds may have these properties and currently, five compounds exuded from sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), signalgrass (Brachiaria humidicola) and rice (Oryza sativa) have been identified; while inhibition has also been observed in wheat (Triticum aestivum) but the specific biochemical has not been identified2. Brassicas are of course well known nitrate accumulators7,8 but perhaps there is merit in including sorghum and rice in cover crop blends to support nitrogen retention.

C-based Inputs

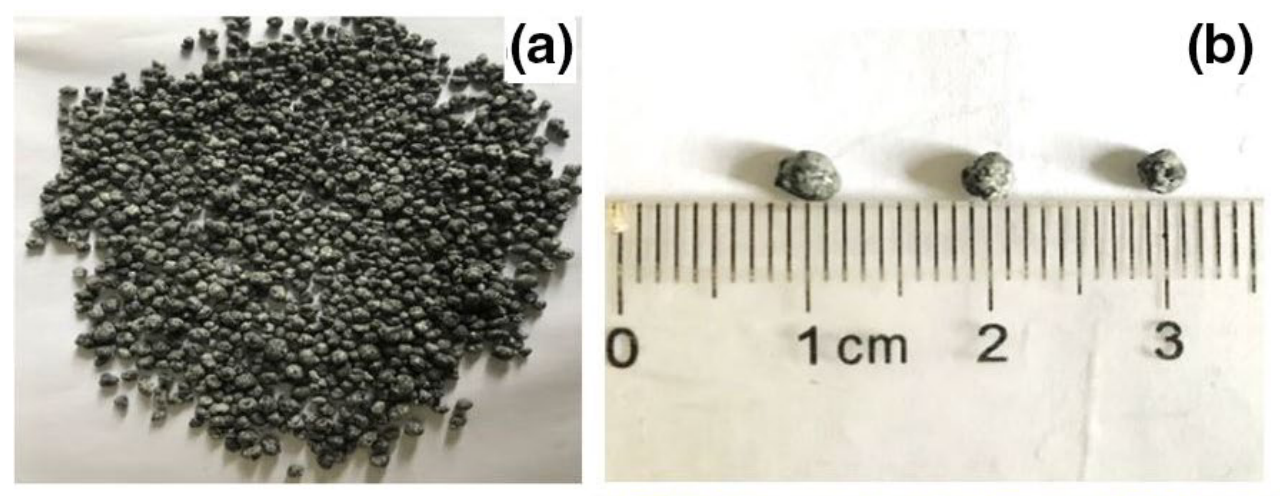

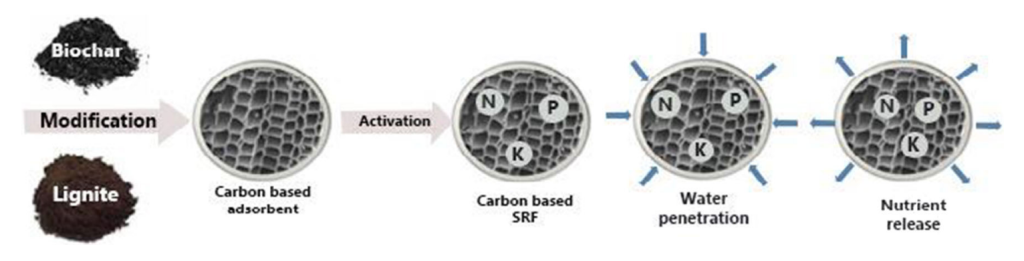

C-based inputs that have demonstrated an ability to stabilise N include humic and fulvic acids, molasses, biochar, oil-based compounds and raw humates (Figure 1). Beyond C inputs, coating fertiliser granules with inorganic nutrients such as sulphur, ammonium thiosulphate, zinc or boron has also been demonstrated to induce a slow-release mechanism of the N.

Figure 1: C-based inputs such as biochar and humates help induce a slow-release fertiliser effect when combined with nutrients.

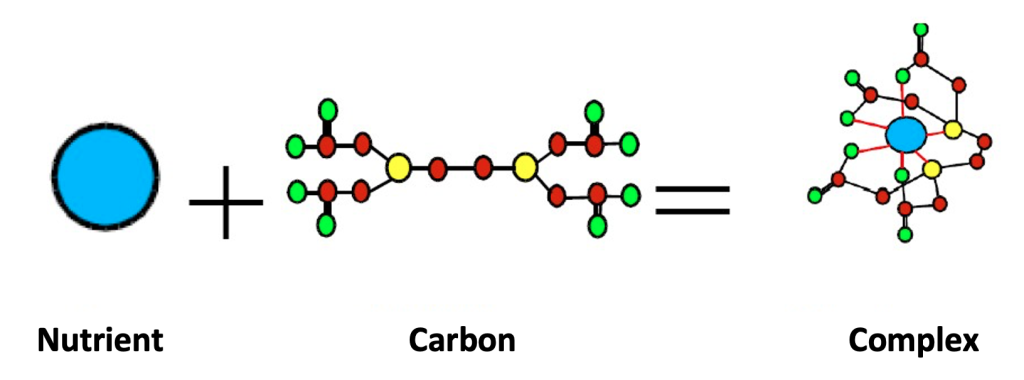

The mode of action of C-based inputs is really quite straight forward – rather than apply highly available and reactive N as simple ions in an inorganic form, by combining them with a C source, the C acts like a sponge to bind and complex the N into a larger C-N based molecule. Figure 2 depicts the complexing of a simple ion into an organically bound, larger molecule. The C atoms that bind to the N ultimately stabilise the N preventing volatilisation and/or conversion into nitrates and also prevents the leaching of nitrates due the highly charged surfaces of the C sponge that attaches to soil particles and keeps the complex in the root zone.

Figure 2: Including a carbon source with soluble nutrients forms a carbon-nutrient complex with greater stability.

By combining nitrogen inputs with humic and/or fulvic acids, studies have demonstrated reductions in ammonia volatilisation4–6,9,10, reductions in nitrous oxide emissions5,11, increases in soil ammonium3,5,9–12 and nitrate10,11 retention, increases in yield/biomass/plant growth11–16 and nitrogen use efficiency11–14,16. Even humates or the raw brown coals that humic and fulvic acids are typically extracted from have also been used to stabilise N and improve N retention in the soil17–19. Of course, even composts and manures contain a range of humic type substances which can also provide this benefit when these organic amendments are used in conjunction with conventional fertilisers – a best of both worlds approach.

Despite molasses having nowhere near as high exchange capacity as humic or fulvic acids, a study from Australia in sugarcane demonstrated that when combined with liquid fertiliser, molasses stimulated the soil biology to immobilise the nitrogen by consuming it along with the carbohydrates from the molasses. This essentially tied up the N within the living microbial biomass which created a slow-release mechanism for N release at a later date. This study demonstrated that the biology immobilised 18% of the nitrate within 2 hours and 95% of the nitrate by the fourth day of incubation20. This highlights the high digestibility (and biostimulant effect) of the C in molasses provides an alternative pathway for N stabilisation as compared the C sponge provided by humic substances that binds to the nutrient.

Lastly, the number of studies on biochar has truly exploded in recent years, it astounds me how many papers are coming out exploring the various benefits to this input. Whether it’s combining it with compost, fertilisers, biofertilisers, animal feed or direct soil application, biochar has great potential to be an invaluable input, providing the economics of use can stack up (which they don’t always at this stage). In relation to combining with fertilisers, biochar has demonstrated an ability to reduce nitrogen losses from the soil, improve nitrogen retention, increase nitrogen use efficiency and increase plant growth21–23.

In Practice

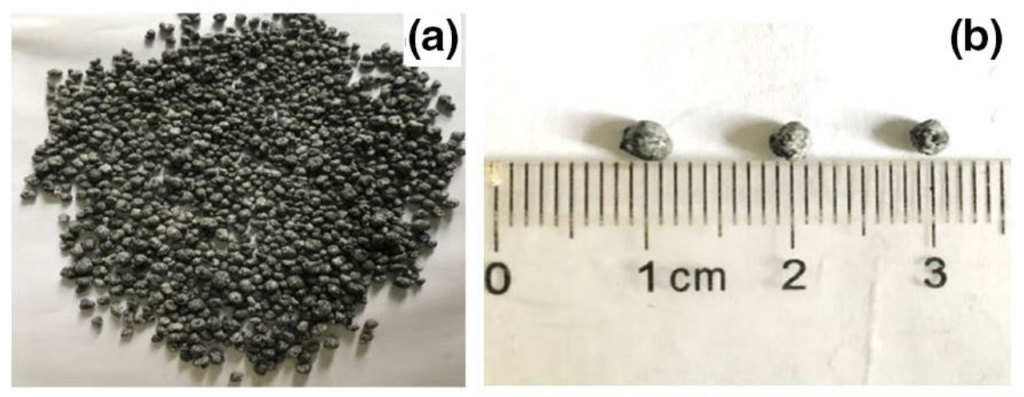

Carbon based inputs are most easily and effectively implemented with fluid fertilisers as the fully soluble C and N can easily bind together when in liquid suspension. Liquids can also be used to coat fertiliser prills, typically used at a rate of around 6-8 L of C source per tonne of fertiliser. Dry powders can also be used to coat or dust fertiliser granules such as depicted in Figure 3 using biochar. Although it is more effective to physically combine the C and nutrients in the same application, it is still possible in a more general sense to apply this concept in an integrated manner wherever organic amendments are used in conjunction with fertiliser inputs. The various strategies that can be used to build soil C ultimately will help provide a C sponge for stabilisation in the soil. That said, the argument for additionally including external C sources with fertiliser inputs is so that the soil C can be preserved whilst using/cycling the added C. In closing, synthetic inhibitors are powerful and targeted tools to help minimise nitrogen losses and I broadly support their judicious use in highly leaky and vulnerable contexts. However, C-based inputs provide additional soil health related benefits beyond N stabilisation and without concerns of plant toxicity. Consequently, C-based inputs have my vote due to the multifunctionality and multiple benefits that their use can bring over and above N stabilisation.

Figure 3: Example of C coated fertiliser granules.

References

1. How Plant Root Exudates Shape the Nitrogen Cycle (2017). doi.org/10.1016/J.TPLANTS.2017.05.004

2. Nitrogen transformations in modern agriculture and the role of biological nitrification inhibition (2017). doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2017.74

3. Understanding the Role of Humic Acids on Crop Performance and Soil Health (2022). doi.org/10.3389/FAGRO.2022.848621/BIBTEX

4. Volatilization of ammonia from urea-ammonium nitrate solutions as influenced by organic and inorganic additives (1990). doi.org/10.1007/BF01063338

5. The effects of humic acid urea and polyaspartic acid urea on reducing nitrogen loss compared with urea (2020). doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.10482

6. Inhibition of urease activity by humic acid extracted from sludge fermentation liquid (2019). doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121767

7. Cover Crops Reduce Nitrate Leaching in Agroecosystems:A Global Meta-Analysis (2018). doi.org/10.2134/jeq2018.03.0107

8. Cover crop crucifer-legume mixtures provide effective nitrate catch crop and nitrogen green manure ecosystem services (2018). doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.11.017

9. Reduction of ammonia loss by mixing urea with liquid humic and fulvic acids isolated from tropical peat soil (2009). doi.org/10.3844/AJAB.2009.18.23

10. Reducing Ammonia Loss from Urea by Mixing with Humic and Fulvic Acids Isolated from Coal (2009). doi.org/10.3844/ajessp.2009.420.426

11. Effects of Humic Acid Added to Controlled-Release Fertilizer on Summer Maize Yield, Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Greenhouse Gas Emission (2022). doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12040448

12. The Combined Application of Urea and Fulvic Acid Solution Improved Maize Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism (2022). doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12061400

13. Carbon-Based Slow-Release Fertilizers for Efficient Nutrient Management: Synthesis, Applications, and Future Research Needs (2021). doi.org/10.1007/s42729-021-00429-9

14. Co-addition of humic substances and humic acids with urea enhances foliar nitrogen use efficiency in sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) (2020). doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05100

15. Greenhouse pot trials to determine the efficacy of Black Urea compared to other nitrogen sources (2009). doi.org/10.1080/00103620802697988

16. Humic Acids Incorporated into Urea at Different Proportions Increased Winter Wheat Yield and Optimized Fertilizer-Nitrogen Fate (2022). doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12071526

17. A slow release brown coal-urea fertiliser reduced gaseous N loss from soil and increased silver beet yield and N uptake (2019). doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.145

18. Hybrid brown coal-urea fertiliser reduces nitrogen loss compared to urea alone (2017). doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.270

19. Nitrogen Dynamics in Soil Fertilized with Slow Release Brown Coal-Urea Fertilizers (2018). doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32787-3

20. Harnessing microbial ‘slow-release’ to improve fertiliser profitability and sustainability (2018).

21. Assessing the impacts of biochar-blended urea on nitrogen use efficiency and soil retention in wheat production (2022). doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12904

22. Biochar bound urea boosts plant growth and reduces nitrogen leaching (2020). doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134424

23. Co-application of biochar and nitrogen fertilizer reduced nitrogen losses from soil (2021). doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248100

-

Farmer Focus – John Cherry

January 2023

It’s certainly been an odd year. The hot and dry summer made for an easy harvest, but our spring crops were very poor with the slow, or even non-existent start, that most of them had. I’m sure I was whinging about this in the June edition. We didn’t even plant a lot of the planned spring crops as the ground was too dry, we substituted millet for linseed as it seemed feasible that we’d at least get a crop of that from an early June sowing.

So we slotted some Mammoth millet in after we had a nice little half an inch of rain in early June and most of it came, but unfortunately it never got much taller than six inches, which made combining (in October) interesting, but didn’t exactly keep the corn-carts busy. In fact we got forty acres worth in one combine tank, but it was better than nothing and very cheap to grow.

Mulika spring wheat was drilled earlier and started growing but rather lost its way and didn’t bring us much more than a tonne an acre, the spring oats looked fantastic, but were burnt off by the really hot spell and again just hobbled over the finish line with a disappointing little heap in the grainstore. Luckily the winter crops did fill the sheds and they are happily valuable!

We had a field or two where we never sprayed off the over-winter cover crops as we couldn’t see the point of having bare ground over summer if it wasn’t going to ever rain again and these gave us some welcome silage, having a bit of westerwolds in the mix paid dividends on that front. Likewise, a field of grass seed that was too dirty to make the grade for seed gave us several hundred very welcome round bales of hay, which we are only just beginning to feed to the cattle now that they’ve finally caught up with the wedge of grass that we’d managed to keep in front of them all summer.

The cattle have done well this year, although their growth rates suffered a little in the heat, they look great going into winter. We bang on about the five principles of regenerative farming, but there’s no hiding the fact that we fall short on a lot of our arable land…there’s often exposed soil, single species cropping and the only grazing animals they might encounter are deer and the odd hare. I think a multi-species grazable summer cover crop would have a far better chance of getting going in these cold dry springs (or indeed any other kind of spring) than a monoculture of spring barley or wheat and be a lot more fun to harvest with a mob of fattening cattle.

A crop like that ticks all the boxes when it comes to the principles: no disturbance, living roots in the ground all year, constant ground cover, lots of diversity and grazing animals would be there. Herbal leys are even better as you get four years of maximum box ticking for your money. Once established they don’t need anything spent on them, which always helps with cash-flow. And the ground is transformed at the end.

We’re now beginning to work on another exciting Groundswell programme for next year (stick it in your diaries if you haven’t already done so: 28th and 29th of June 2023…it doesn’t clash with Glastonbury this year for those of you that worry about that sort of thing!). The sessions application process is open now for anybody who fancies giving a talk or creating a panel to discuss any aspect pertinent to Regeneration, just fill in the form on the website:

We’ll go through them all in the spring and try to find the best!

We have a few trial plots already established and all sorts of new things in the pipeline to pique the interest of attendees. It is extraordinary and pleasing how quickly the whole RA scene is evolving and growing, especially how much attention that it is getting from people outside agriculture. This is inevitably resulting in calls for some kind of accreditation scheme so that the food industry can cash in by selling ‘regeneratively grown’ food at a premium.

Personally I think this would be counter-productive as one of the joys about the regenerative approach is the option of dipping your feet in by trying different things that complement conventional techniques and just working out what works best on your farm. The organic lobby managed to create a set of rules that practitioners have to follow, which works quite well, but it did make for a bit of a ‘them and us’ world, where, for instance, conventional farmers didn’t think of using cover crops (which have been an organic staple for years) as they didn’t think it was relevant or useful for their farms.

We’re working on a definition of regenerative agriculture on this basis, we are all on a journey, it’s a movement after all, we’re just moving at different speeds. We are going to ramp up our colour coding for sessions this year, so we hope it’ll be easier to pick out talks that are relevant to where you are on your journey. We are planning some meatier topics and talks for those who have heard the general guff too many times. We’re particularly excited that Nicole Masters is going to be there. Having just attended her two day course organised by the Land Gardeners at Althorp, I know just how mind-bendingly fascinating she can be.

We had a wonderful day here in October with the Understanding Ag team from America (Gabe Brown, Allen Williams and Shane New), who were over this side of the pond for other reasons and had a spare day in their schedule, so we grabbed them and 300 of you came to hear them talk and inspire. It gave me renewed enthusiasm to expand Groundswell beyond a once a year event. We are currently working on a Groundswell X type mini festival in Scotland sometime in the summer, more on which later. There is so much dynamic stuff going on in Scotland and we always have an amazing contingent who come all the way down to Hertfordshire…I don’t want them not to come but I think a Northern focussed event would be fantastic to go to as well!

-

Soil Fertility Services

Written by Steve Hollaway, Soil Fertility Services

Ask anyone to define healthy soil and you will get a multitude of varying replies that will probably include having a good number of worms; friable soil with a texture that’s similar to chocolate cake; unhindered vigorous crop rooting and so on…

But, have you considered what must happen first? After all, these factors must surely be a consequence of having healthy soil.

Some will say that no-till will, by its own action (or lack of it), over time encourage natural improvements; after all, you minimise soil disturbance thereby allowing its inhabitants to carry about their daily business and fungi will be free to make their intertwining networks throughout the soil’s profile, symbiotically extending a crop’s root system and liberating vital locked up elements. So if the mere mention of using steel to aerate sounds like heresy, then you need to read on!

Ask yourself, what would a soil do if left alone? It would first begin the process of self-healing, covering itself with natural protection against the harmful and sometimes damaging elements – that might involve growing weeds. As this armour continues to spread across the surface, it also sets down its sugar factories (it’s roots) into the earth, each one creating tiny biological highways that act like conduits for water and air. As the atmosphere in these biomes begins to improve, so too does its ‘Bio’ inhabitants’ ability to maintain and build a more resilient soil ecosystem.

Unlike bacterial life, fungi are slower to develop their associations and networks, but remember, they are picky bedfellows and won’t choose to communicate with every plant. In general terms it is agreed, that the longer a soil gets left to its own devices, the more it shifts to be fungal-dominated; but is that what you really want, after all, cereals prefer a slightly bacterial-dominated soil.

In a nature-led system, you would see migrating animals both grazing and fertilising, cycling nutrients and often the mere act of travelling through would create some soil disturbance, so the system supports itself quite well without any intervention either chemically or from steel. If we said that steel is the answer to improving soil aeration you would probably throw your hands in the air but hear me out first…

“The heresy of one age becomes the orthodoxy of the next” – Helen Keller

When Grandad had his Massey 35 and went ploughing, it was done by eye – slow and steady and considered; with minimal horsepower came the limiting restriction on how deep and how much soil could actually be turned over. He felt that when he ploughed, the soil was actively getting a reset and it probably was, but you do not need a reset every year, far betterto haveaprescriptive tillage approach to match individual field needs.

Over 50 years ago Americans started using anionic surfactants as a way of ‘opening up’ their soils; these products were applied with a sprayer directly to the soil, whereby they allowed bound water and locked together elements to move more freely, thus creating a much-improved soil environment for roots and biological life to flourish.

As gravity pulled these products down through the contours of the soil they continued to condition and improve air and water infiltration; with sustained use, these would become very efficient pan busters.

Back in the 1990’s Soil Fertility Services was the first to bring this sometimes called “Snake Oil” across the water, whereby it evolved into the product that it is today.

So, you’re still ‘Re-gen’? Remember that does not necessarily make you ‘New-gen’; make the most of the lessons and experiences of the past as you move to the future.

-

KUHN launches new lightweight drill

KUHN has unveiled an updated, lightweight Megant drill featuring new tine coulters, an updated terminal, and the option to add a second hopper. The Megant 602R shares functionality with the previous 600 model, but features half width shut off and can be specified with an additional SH 1120, 110 litre hopper to drill two crops in the same pass.

Due to its lightweight design, the Megant can be operated by tractors with as little as 150 horsepower. Three types of tines can be specified on the Megant, including reversible forward action, straight, and a new narrow 12mm straight tine coulter which reduces soil displacement through improved penetration and also reduces wear on the tine thanks to the addition of carbide plated points.

A new VT 30 terminal makes the Megant suitable for tractors with and without ISOBUS. Large buttons, a shock proof casing and ergonomic design make the terminal easier to operate and more durable. Compatibility with both KUHN CC1 800-1200 and other ISOBUS terminals will make the Megant more accessible to all users and will offer the economy of not needing to purchase a second control terminal for tractors already fitted with a compatible model.

The 602R has inherited some features from the larger ESPRO drill including spring loaded nonstop track eradicators and side markers that are better suited to dry conditions. A new welded 1800 litre hopper capable of holding 1200 kilos of wheat and drilling 60 hectares a day replaces a riveted hopper on the previous model. The new hopper also includes internal steps to improve access to the distribution head.

New tines, half width shut off, greater connectivity and the ability to add a second hopper will make the Megant an attractive option. The improved hopper features a shut off door enabling operators to isolate the two compartments. This makes it possible to adjust the metering unit when the hopper is full and helps to prevent seed settling in the metering unit when the Megant is in transit.

The Megant has been fitted with KUHN’s VISTAFLOW valves which can be configured and controlled from the terminal. This enables operators to program the flow of seed with the option to save settings for future use. VISTAFLOW also records tramlining configurations such as the working width and wheel track to enable more accurate use of sprayers and fertiliser spreaders which will help to reduce input costs.

The Megant 602R is available to order in the UK with RRP’s starting at £42,760.

-

Learning from the bottom up

Last week I was at an event where inspiring farmers – in this case Nick Down, David Miller, and Nik Renison – showcased, with the pictures to prove it, some of the brilliant innovations they have pioneered on their farms. And they really were inspiring, with a palpable buzz in the full-house audience as they spoke.

Conferences like this one last week make clear that farmers want to learn from other farmers. Credit: @PhilipCaseFW / Mark Allen Group / Twitter 2022

Moments like this highlight – at least to me – that farmers really want to learn from other farmers. Or consider other examples like Groundswell or Carbon Calling. Or the farmer clusters that have sprouted like mushrooms. Or the networks of Monitor Farms and Demonstration Farms and Strategic Farms. Or the countless discussions on Twitter and The Farming Forum. Together it seems glaringly obvious that farmers want to learn in this way: from each other.

But if this is so, why is agricultural research conducted in almost precisely the opposite way?

Agricultural research is based on plot trials, not farmers learning from other farmers. Why? Credit: Michael Trolove / Cereal trial plot, Cereals 2010 / CC BY-SA 2.0

There are plot trials in carefully controlled conditions, with replicates, and then peer reviewed results are trickled down to farmers. Surely Liz Truss proved to destruction that trickle down is not the best way of running things? The results of studies and trials are too often irrelevant to farmers who are in different contexts to those the trial was conducted in – on different soils say, or with a different climate. Or they simply couldn’t work at the scale of a real farming system.

What if we could do agricultural research in a different way? What if we could harness the fact that farmers are naturally scientists who have already been experimenting on their fields for decades in most cases. As Nick and David and Nik all showed, there are new innovations already being proven on farms and, by definition, these are actually working at farm scale. And if we look at all the farms trying new things – i.e., practically every farm in one way or another – between them there are innovations there that any other farm could benefit from.

Can we harness these on-farm innovations in order to help every farm maximise its potential to grow healthy food, profitably, and in a way that restores rather than degrades the land? Can we make farmer to farmer learning the basis of agricultural research?

I think the answer is yes, but to do so we will need to get past some challenges.

- Farmers aren’t running replicated trials or monitoring a thousand parameters in every field – is this really valid science other farmers can learn from?

The key here is zooming out. One farm – say an arable farm with 30 fields – is in effect conducting 30 experiments each year. That’s not much compared to a researcher with many tens or hundreds of replicates. But when you start looking at many farms, going back many years, you quickly see that farmers have effectively run thousands, if not millions of on-farm ‘experiments’.

Every crop grown in every field each year is in effect an ‘experiment’ – why don’t we use this as a basis for agricultural research? Credit: Jan Kopřiva / Unsplash

And while they haven’t been monitoring each one as precisely as a scientific trial, there is still a wealth of information that is usually recorded – from soil samples, to yields, to inputs applied, to tillage practices used – on each of those ‘experiments’. This information is currently just sitting siloed and under-utilised on most farms.

Projects like the AHDB funded SMIS have shown that by looking at this siloed information together it’s possible to uncover new insights that are practically useful for farmers. Things like:

- On what soil types does sugar beet have the least impact on subsequent yields?

- What rotation most improves organic matter levels on different soil types?

There are so many potential questions that can be answered in this way. And this one resource of on-farm information can answer many more specific questions than the ‘one problem at a time’ approach of traditional replicated trials can. Added to that, traditional research approaches struggle to look at the long cycle of a full rotation because of time-limited funding cycles. In contrast, looking at the existing information going back over one or two rotations from a range of farms can answer specific questions that reflect on-farm practice.

- Even if on-farm innovation can be the basis for research, how are the findings any more relevant than in the current top-down system?

Clearly all the initiatives outlined earlier, from conferences to monitor farms to magazines like the one you are reading now, are a good way of disseminating knowledge. And even if new research, like that outlined above, was based on existing on-farm information this would still apply. But this new approach could also enable a new dissemination option – one which more directly links to that original observation: farmers learn best from other farmers.

For example, if we combine information on how all of these on-farm ‘experiments’ have been conducted with the rich array of environmental data that we’re fortunate to have in the UK, we can allow farms to compare themselves against other similar farms based on any combination of variables including farm type, geology, soil type, and climate. This then allows the findings of this new, farm-based research, to be tailored so that farmers are presented with the research that is relevant for each one of their fields.

This new approach could not only uncover new types of insight and knowledge that no plot trial would ever have the scale to discover. But it would also nip in the bud one of the biggest gripes levelled at agricultural research: ‘that wouldn’t work on my farm’. The insights that farmers see could be based on the fields of other farms that are like theirs. They could even be put in touch with those other farmers directly to discuss the findings.

Join the bottom-up approach!

We have launched a new partnership between Soil Benchmark and Cranfield University to build this new model for bottom-up agricultural research. For the approach to work it needs the participation of farmers from across the country, whose fields together cover every major soil type and every major cropping system. We are welcoming farmers from all over England to join us, with 65,000 acres already signed up.

Get in touch if you’d like to get involved, and turn the existing information you’ve already collected on your fields into the research of tomorrow!

Dr Ben Butler is the Chief Scientific Officer of Soil Benchmark, a DEFRA funded start-up working alongside NIAB and ADAS, looking to help farmers learn from the existing data they have already collected on their farms.

-

Correcting myths around carbon markets could unlock income of thousands of pounds for UK farmers

Written by Andrew Voysey, Chief Impact Officer, Soil Capital

UK agriculture could benefit from payments worth as much as £500m every year if myths around carbon markets are corrected. But the industry must work harder to ensure farmers are presented with the best information about the opportunities on offer.

This was the conclusion of an industry roundtable that the agronomy firm I represent, Soil Capital, convened this Autumn with farmer, Andrew Randall, at his farm in Maidenhead. As well as farmers, the event was attended by representatives from industry bodies like the NFU, CLA, AHDB and the Association of Independent Crop Consultants, as well as land agents and all of the major distributors.

Recently published minimum requirements for Soil Carbon Codes in the UK should provide reassurance that those already using international standards are taking high integrity approaches to measuring, reporting and verifying soil carbon improvements.

But other deep-rooted beliefs, some of them based on conflicting and incomplete information, that currently hold farmers back will still persist even when clarity on standards is improved.

The event therefore focused on how to correct the most important misunderstandings about how carbon markets work so that more growers feel empowered to enter the market. Let’s review the key talking points.

Myth 1: If I trade all my carbon now, I may regret it if I need it in the future

Even degraded soil still contains carbon and many farmers believe that “carbon trading” relates to all of the stock of carbon that exists in their soil before they even enter a carbon payment scheme. Therefore, the decision can take on significant implications – as if it was about trading away mining rights – and even appear to be potentially life-changing.

In reality, carbon markets only pay for carbon added to the soil on-farm each year a farmer participates in a carbon payment scheme — not for any carbon that was already locked up in the soil many years before the farmer joined the scheme.

Myth 2: If I trade carbon, I am just giving big emitters the right to pollute

When thinking about what carbon markets do, most of us think quickly of offsetting – enabling high polluting companies to compensate for their emissions by paying others to reduce theirs.

Farmers undertaking the risk of changing their management practices to achieve such reductions can feel that this is either an unfair exchange or, frankly, an immoral one.

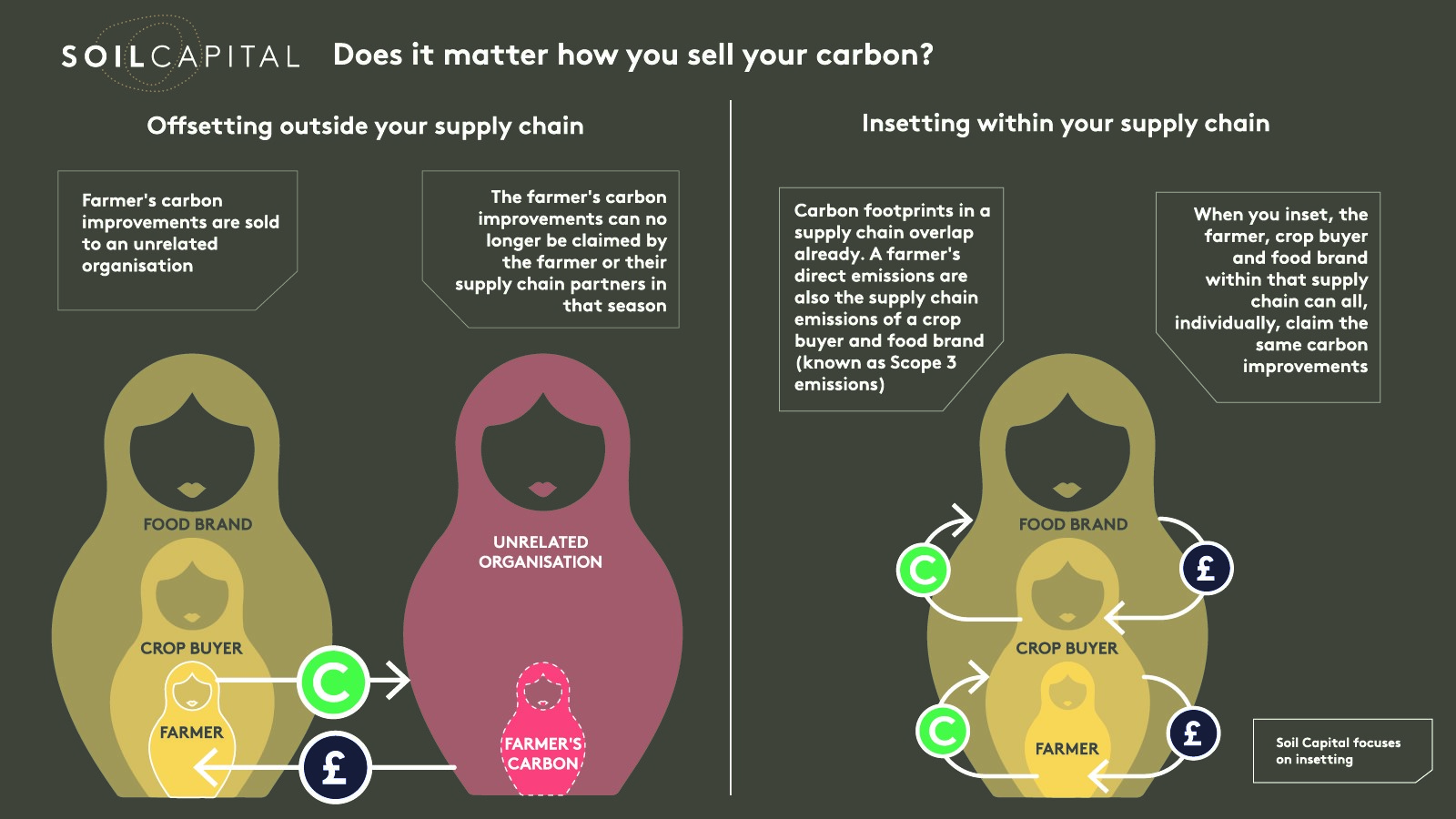

In practice, there are two quite different types of carbon trading within the carbon markets:

· Offsetting outside your supply chain – when the claim to the farmer’s carbon improvements is transferred to an unrelated organisation outside of the farmer’s own supply chain

· Insetting within your supply chain – when a company that buys the farmer’s crops also pays for the farmer’s carbon improvements, on the basis that the farmer’s carbon footprint is actually already part of the food brand’s carbon footprint by virtue of their supply chain connection

With this knowledge, farmers can see that trading carbon does not have to be about enabling big emitters to offset their emissions.

Myth 3: If I trade carbon now, I won’t be able to meet ‘net zero’ requirements in the future

Farmers are aware that the supply chain may impose net zero requirements at some point. Since many believe that offsetting is the only way to engage with carbon markets – and when an offsetting company buys the rights to the farmer’s carbon improvements, the farmer can no longer claim those carbon improvements – this can understandably make farmers nervous about making such a commitment.

But when a farmer’s carbon improvements are sold within the supply chain, as insets, those carbon improvements can be claimed by the farmer as well as the crop buyer and food brand. This is on the logic that there was already overlap between the carbon footprints of these entities before the trade happened because of the way that the carbon footprint of supply chains are constructed.

This means that, if they engage in insetting, farmers do not need to be concerned about being able to meet supply chain net zero requirements. To the contrary, by insetting, they will have benefited from payments that help them arrive at (and go beyond) this point.

Myth 4: I have to get to ‘net zero’ before I can get paid for carbon

The typical farm today emits carbon overall, but many farm systems have the potential to not only get to net zero but go beyond that and take carbon out of the atmosphere on a net basis each year. Many farmers believe that the carbon markets are only accessible once you have got to net zero.

Carbon markets have always existed, first and foremost, to reward people for reducing emissions. This is true across all industries. This is because reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the most economically efficient way has always been a firm priority in combatting climate change.

From the market’s point of view therefore, farmers do not have to already be ‘net zero’ in order to get paid for carbon. For a farm that is net emitting greenhouse gas emissions today, revenue from a carbon payment scheme can be part of a transition payment to change management practices, up to and beyond net zero.

Myth 5: Carbon prices will only rise, so it’s in my interests to wait before I value my carbon

Carbon credits tend to have higher value when they have been more recently generated through a verified scheme, since the market recognises that over time, the standards and approaches underpinning such schemes will generally improve. Generating carbon credits and then holding on to them to sell later may therefore actually not generate the best prices.

Farmer Focus

Berkshire farmer Andrew Randall, who hosted the round table on his 240ha arable farm, signed up to our certified carbon payment scheme earlier this year after researching the market and realising much of what he’d heard about carbon markets was incorrect.

He told attendees he expects to make about £50/ha in his first year by implementing practices such as direct drilling, growing multi-species cover crops, reducing nitrogen use and spreading sewage sludge.

“When people started talking about carbon payments I realised we were ticking a lot of boxes with what we wanted to do on farm and that we could capitalise on that,” he said.

“A lot of the farm-level chat has been ‘don’t sell the rights to all the carbon under your feet’, which is a huge myth that needs to be busted. I’m not selling a bank of carbon — I’m benefitting annually from the practices we do on farm, and if we don’t benefit financially from those environmental gains we’re making, it’s simply a wasted opportunity,” he added.

Mr Randall said with the combination of his planned practices, he expected to net sequester at least 2 tonnes of carbon per hectare/year.

“That will hopefully see us make over £10,000 this year, which is a useful way of starting to get back what we’re losing from the basic payment scheme,” he added.

“It has been a leap of faith in some respects, but by doing my research and getting good advice I don’t regret signing up, and I’m considering whether to bring another farm into the scheme.

Soil Capital Carbon – a proven entity

Following an external audit against the ISO standard that the scheme is certified against, Soil Capital Carbon has already disbursed its first payments to European arable farmers in June this year. Nearly €1 million was paid to 100 French and Belgian farmers on the back of practices they implemented in the previous season.

Today more than 650 farmers have enrolled overall. The programme was introduced to the UK last year, with 50 farmers having completed their first carbon assessments so far. Soil Capital targets the inset market, with the vast majority of carbon payments coming from the food and agri supply chain from agribusinesses like Cargill, AB InBev and Royal Canin (Mars Group) in support of those companies’ commitments to reduce their supply chain emissions.

These payments are the first new revenues Soil Capital has generated for farmers in Western Europe from reducing the carbon footprint of agriculture. Until now, all this has been a bit abstract. What’s more, these carbon payments are higher than the initial commitment made to farmers. Thanks to better sales prices secured with buyers, Soil Capital’s minimum guaranteed price of £23/t was raised to £27, which is a good sign. On average, farmers received £8,500 per farm in their first year. These first payments confirm the robustness and credibility of the Soil Capital programme with farmers and food companies. It is clear that farmers value the fertility and resilience benefits of improving soil health by holding more carbon in their soils. The carbon payments Soil Capital unlocks offer a meaningful incentive to farmers to undertake the difficult work of changing practices or, in some cases, maintaining those with a net positive impact. Some of the concerns in farmers’ minds are based on misunderstandings and must be corrected. Others are perfectly reasonable and need careful consideration – for which Soil Capital is happy to help.

-

Farmer Focus – Andy Howard

January 2023

French Style Harvest

Since my last article in May harvest has been and gone (very quickly) and all the winter crops have been established and are looking well. This harvest it felt like we were farming in France. Most was done by the end of the first week in August and due to everything being so dry we couldn’t plant any grass seed or cover crops. I have always been jealous of the French farmers being able to take most of August off and enjoy the summer. I got a taste of it this year, for the first time in our relationship I spent the day with my other half on her birthday (I took the 11th of August off!!). I saw my children a lot and had days out with them during their summer holidays. It was great to have so much family time, maybe I need to start searching for farms in France or maybe climate change will make this a regular occurrence?

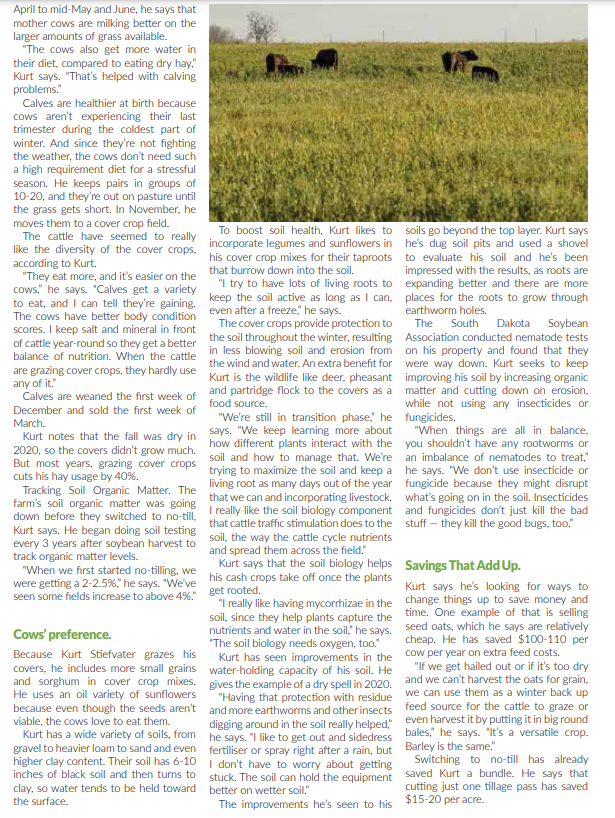

In my May article I talked a lot about the trials we had in the ground and I was going to go through the results in this article. With the talk of hot weather in the previous paragraph, this links in well to our experiment with growing Lentils and Camelina together (see picture). This seemed to be the only spring crop that coped with the 40 degree C temperatures and yielded well. We tried various seed rates of camelina and have come to the conclusion that the best thing will be to roll twice and add a few slug pellets when drilling in the future. The best establishment of Camelina was on the headland, which is always telling.

We had various trials in wheat. The first one was using Nurture 60 foliar to replace bagged Nitrogen. One area had 70/kg/ha/N bagged and then Nurture 60. The other had 140kg/ha/N and no Nurture 60. There was no noticeable difference in yield between the two. There was also no noticeable visual difference either as I did not tell anyone about this trial, and no one could pick it out as it all looked the same.

The second trial in wheat was comparing various foliar nitrogen treatments for lifting protein content. We had a control plot, AF nitrogen plot and a Nufol plot. The clear winner by a decent margin was Nufol. It increased our protein by 1.5% in this trial and has allowed our wheat to go for milling. Even though I grumbled at the exorbitant cost of it at the time it has had a great ROI this year.

The final trial in wheat this year was comparing our variety blend to a single variety (Crusoe). I had two trials in two separate fields. In the first the yield increase from the blend was 1.2t/ha and in the second field it was 0.6t/ha. This is a great result but does need some context. The trials were on light land and the variety was Crusoe which can in dry years struggle with the lack of water. Next year if the trials are on heavier ground and comparing to Extase for example and we get enough moisture, we may not see such dramatic results. Though, I was recently speaking at The Association of Applied Biologists conference and NIAB presented their trial results on variety blends, which showed very encouraging results as well. At the same conference I heard a researcher talk about coffee growing in Java. She talked about how the government in the 1990’s promoted and backed IPM and this led to a 90% reduction in pesticide usage. It is amazing what can happen if government, academia and farmers work together! DEFRA are you listening?

Finally, we did a small trial on spring linseed to look at whether adding compost extract down with the seed would have any effect. We did see 13% yield bump, which is encouraging, though it was only a small area in just one year. I know that Ben Taylor Davies had phenomenal results using extracts on potatoes. All this has encouraged me to widen our usage of extracts this year. All our wheat had compost extract, except for numerous control strips in fields. I still feel we have a lot to learn about using them, but early results are encouraging. (Picture of the compost extract in the vortex extractor is attached).

Before I finish, I wanted to talk about an observation from this autumn. We have drilled 2nd wheat into various situations this year, but one sticks out particularly. The wheat pictured is a second wheat where the crop 2 years ago was herbage seed. These crops are twice the size of other 2nd wheats that haven’t had grass in the rotation. This really highlights the long-term fertility benefits of having grass in your rotation.

My winter is partly going to be spent looking into new projects for the future and I am currently on the train to Edinburgh to investigate one such exciting development. I wish you all luck with your own new projects, Merry Christmas.

-

Trinity Natural Capital Markets welcomes the development of the UK Soil Carbon Code

Commenting on the development of the UK Soil Carbon Code, Trinity Natural Capital Markets managing director, Juan Palomares, explains that this is a positive step forward for farmers as it offers the minimum necessary protection and compliance in UK carbon markets.

“Our involvement in the formation of the code by the Sustainable Soils Alliance included extensive contributions to several sessions during the consultation process. We recognise the carbon landscape is an unfamiliar concept for many farmers so wanted to use our scientific expertise and our extensive practical experience to help shape the basic carbon standards that our sector needs as a minimum,” he adds.

“To ensure the carbon trading landscape is designed with farmers in mind, an important inclusion to the code after our input was to make sure the code covers reduction, removal and retention practices allowing a more holistic approach to carbon management on-farm.”

2-6-2021 ©Tim Scrivener Photographer – 07850 303986 ….Covering Agriculture In The UK…. Another important outcome is linked to the permanence of carbon trading and projects, explains Mr Palomares. “The code now establishes a 10-year period for permanence which ensures carbon trading will be more attainable for more farmers,” he adds.

“Then arguably the most important section within the code that protects farmers and ensures rigorous compliance within the market is the requirement that all models that the code will allow ‘must be validated using the latest scientific guidance for the geography, crops and practices’.

“This is something we have always felt must be included as our industry needs to be basing all work and decisions on the latest science if we are to progress and be accountable on a global playing field.”

Mr Palomares highlights that farmers are aware of carbon sequestration playing a more prominent role going forward for profitability, productivity, and sustainability purposes. “On-farm carbon optimisation is going to be vital for the resilience of UK agriculture and the Code will form the foundations of ensuring this is done in a lawful and compliant way,” he says.

“However, we view these standards very much as the minimum necessary baseline. The ambition should be for a marketplace that is fair, efficient and importantly, virtuous. Farmers should be the ones reaping the benefits of any financial gain from natural capital.

“Otherwise, there is a risk that the market will neither preserve nor produce the outcomes for which it was intended and people become alienated. Trinity Natural Capital Markets was designed with high integrity at the heart, unleashing the full power of the global financial system for the benefit of rural farming communities.”

For more information, please visit www.trinityagtech.com, www.trinitygfp.global and www.trinityncm.com.

-

Major review of the AHDB Recommended Lists gets underway

The first phase of a major review of the Recommended Lists for cereals and oilseeds (RL) is taking place this winter.

Initially, people are being asked to complete a questionnaire as part of efforts to improve the variety trialling project.

The announcement follows a strong endorsement of the RL by levy payers in spring 2022, where the project scored 4.2/5.0 for importance during the Shape the future process, and a pledge by the AHDB Cereals & Oilseeds sector council to conduct a major review of the RL in its five-year sector plan.

Jenna Watts, AHDB Head of Crop Health and IPM, said: “We need to hear from farmers to help us hone the RL so it continues to fit the complex decision-making needs of modern farming businesses.

“This is a thorough review and will leave no stone unturned. It will cover many aspects, from the type and nature of the trials to the way data is analysed and variety decisions are made. It will also investigate how results reach farmers and ensure that the RL continues to deliver the best value to industry.”

Typically, the main RL project runs in five-year phases, with a large-scale public review conducted during each project phase to inform subsequent activity.

During the previous project phase (2016–21), AHDB conducted the ‘Look Ahead’ review. This highlighted the importance of the whole variety package rather than the more traditional focus on yields. In response, the RL changed the way it assessed many traits, including disease resistance and lodging traits. It also led to the development of enhanced digital formats, providing powerful ways to view RL data, such as through the RL app and variety selection tools.

The questionnaire, which can be accessed on the AHDB website by clicking on the QR Code, focuses on levy payer requirements. However, in-depth discussions will also take place at stakeholder meetings and focus groups over the winter to capture the wider requirements of the industry.

A dedicated review steering committee has been established to lead the project and provide recommendations to AHDB on potential improvements to the RL.

Patrick Stephenson, independent crop consultant, AHDB Cereals & Oilseeds sector council member and chair of the RL wheat crop committee, has been appointed to lead the review steering committee.

Patrick said: “This review looks forward and aims to keep the RL robust in the face of numerous challenges facing the industry. With constraints on budgets and small-plot trials, it is not possible to do everything. However, the review will help us focus activity. I am particularly keen to squeeze every ounce of value out of data to make the RL even more relevant to farmers.”

The questionnaire is open until 17 February 2023, with initial results due to be published next spring.

The results will inform the next phase of the review, which involves planning and costing the actions required to improve the RL over the short, medium, and long term.

-

Regenerative farming: a buzzword or here to stay?

This year’s inaugural Down to Earth Event in Shropshire highlighted livestock farmers’ thirst for knowledge for regenerative farming. RABDF Managing Director Matt Knight discusses the event and plans for next year.

Down to Earth was born out of a demand by farmers, the government, milk processors, and consumers to produce dairy products sustainably. The event provided a platform where the livestock industry could come together and see regenerative farming in action and hear from experts about the practical ways to implement it on their farms.

We knew there was a demand for this. Still, we never expected almost 2,000 farmers and industry representatives to descend on Tim Downes’ organic dairy farm in Shropshire in July for the first event.

Regenerative Farming is a buzzword of the moment. You can’t turn on the radio or TV without seeing it mentioned somewhere. It even appeared on billboards at Coldplay’s World Tour, highlighting the demand for such change.

Taking the regenerative farming approach

But the question is, how much change is required by farmers to take a regenerative approach? And is it a word that will die out?

I believe regenerative farming isn’t something that is going away any time soon. The reality is most farmers are probably already doing things on their farms that fall into the regenerative category.

Whether composting their manure, soil testing and directing the correct nutrients and management to their land, or grazing livestock in a way that benefits the mixed grass species they are growing- that could all be branded under the regenerative farming hat.

What is interesting is how it all ties together. Perhaps a better name for it should be ‘circular farming’- changing one thing on your farm can influence another.

This year’s Down to Earth farmer, Tim Downes, said regenerative farming for him was all part of becoming more resilient. He said it captured the farm’s energy, helped maintain profits, and created a better environment for cows and staff.

He focuses on many regenerative farming elements such as water management, agroforestry, using bugs on the farm, and protecting and managing soil health, all of which are interlinked.

The buzz from this year’s event was fantastic, and as such, next year, we will be hosting two Down to Earth events- one in the North and one in the South. Both farms, however, couldn’t be more different. It will give people a flavour of how individual the regenerative farming journey is.

Down to Earth 2023

In Cumbria, our 2023 host farmer is Mark and Jenny Lee, Park House Farm, Torpenhow. They run an organic unit with 175 milking crossbred cows, with 50% of their milk going into their own cheese-making business and the rest sold to First Milk. They aim to achieve their milk’s true value, proofing their farm for the future.

They are certified 100% pasture fed by Pasture for Life and mob-graze their cattle on a 30-40 day rotation using 2.5km of grazing tracks.

They also have areas of silvopasture for grazing and have incorporated 80 pigs into the rotation, which work in poorly performing fields to help improve them. Before bird flu restrictions, 1,800-2,000 free-range broiler chickens were also reared a year, helping improve the pasture through their organic muck.

Our southern host farmer, Neil Baker, couldn’t be more contrasting. He runs a high input, high output indoor herd of 1,800 predominately Holstein cows, which are milked three times a day and produce 55,000l of milk a day. He also has sheep on keep and farms 3,200 acres of owned, rented and contract-farmed land.

He is one of Arla’s regenerative pilot farms and says for him, regenerative farming encompasses much more than simply focussing on the soil. Whilst he admits soils are a big area, he prefers the use of the word ‘circular farming’ over the regenerative farming phrase.

As part of the pilot project, he will be looking to grow maize without any chemical inputs, as well as understanding the economic side by calculating carbon emissions from ‘ghost acres’.

Neil uses digestate from the AD plant on his land on the crops he grows, including wheat, barley, peas and grass. He has started establishing important pollinator corridors, which also provide a barrier for wildlife.

Next year’s Down to Earth events are taking place on 6th July in the North and 21st June in the South. Both events are guaranteed to be interesting, and informative and provide much learning about the regenerative/ circular farming journey. Keep posted for more information at projectdowntoearth.com

-

How can we scale regenerative farming?

Written by Belinda Clarke from Agri-Tech E

How can we scale regenerative farming? Following the COP27 discussions in Egypt, this month we look at mindset, money and markets, and how to harness them to influence a more regenerative approach to food production. A recent report from the Sustainable Markets Initiative (SMI) Task Force suggests a tripling of land under such a management approach is needed (up to around 40% of cropped land globally) to reach the climate goals by 2050 and mitigate the predicted 1.5°C rise in the Earth’s temperature.

How will farmers be rewarded for regenerative agriculture?

The Sustainable Markets Initiative Agribusiness Task Force report ‘Scaling Regenerative Farming: An action plan’ reveals three main reasons why regenerative approaches are not scaling:

- The short-term economic case is not compelling enough for the average farmer

- There is a knowledge gap in how to implement regenerative farming

- Drivers in the value chain aren’t aligned

The reasons why regenerative approaches are yet to be widely adopted are not rocket science – either the economic case is weak, there is a knowledge gap around implementation, or the drivers in the value chain are misaligned with the positive (sometimes costly) changes that farmers are making on the ground.

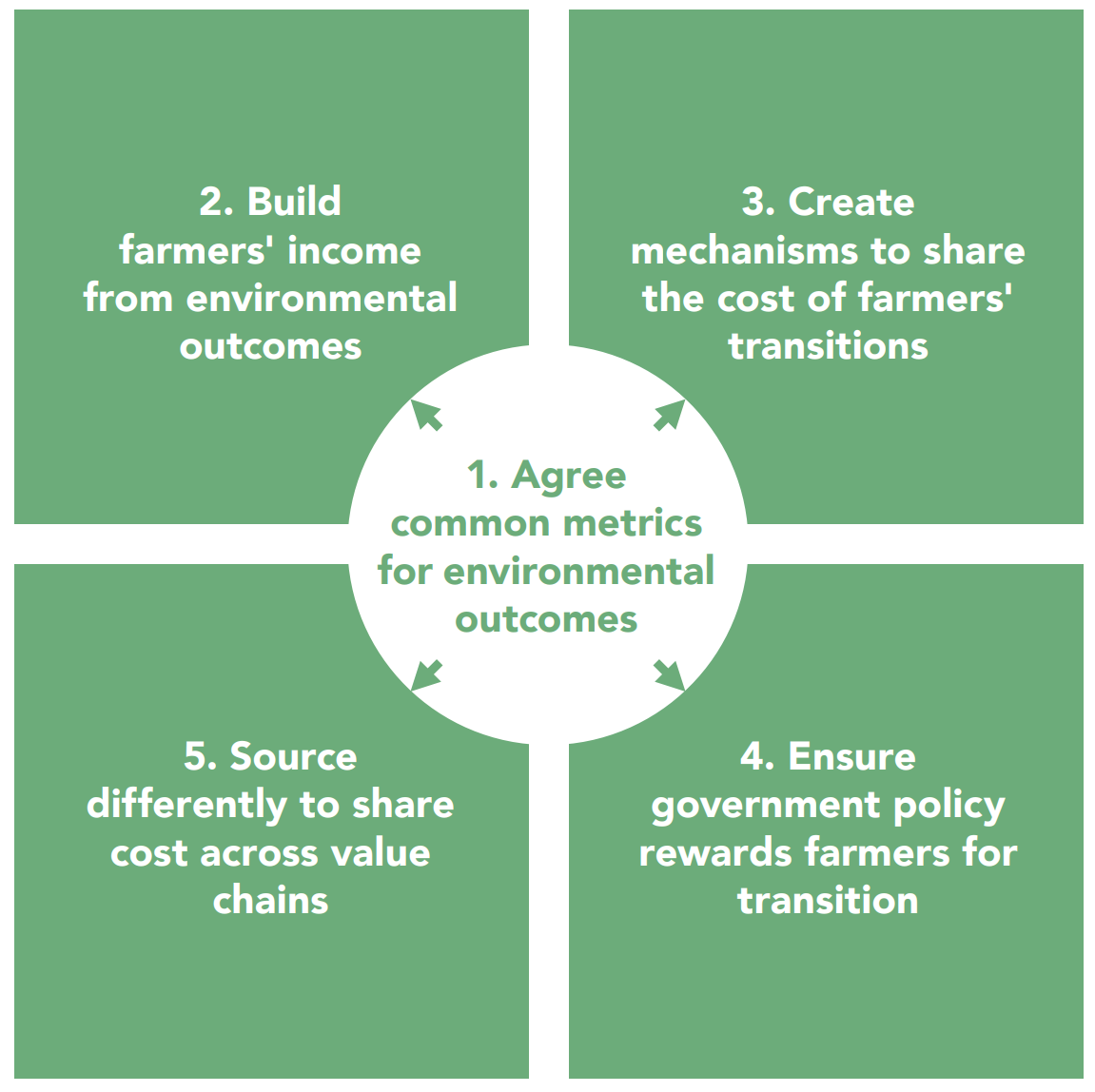

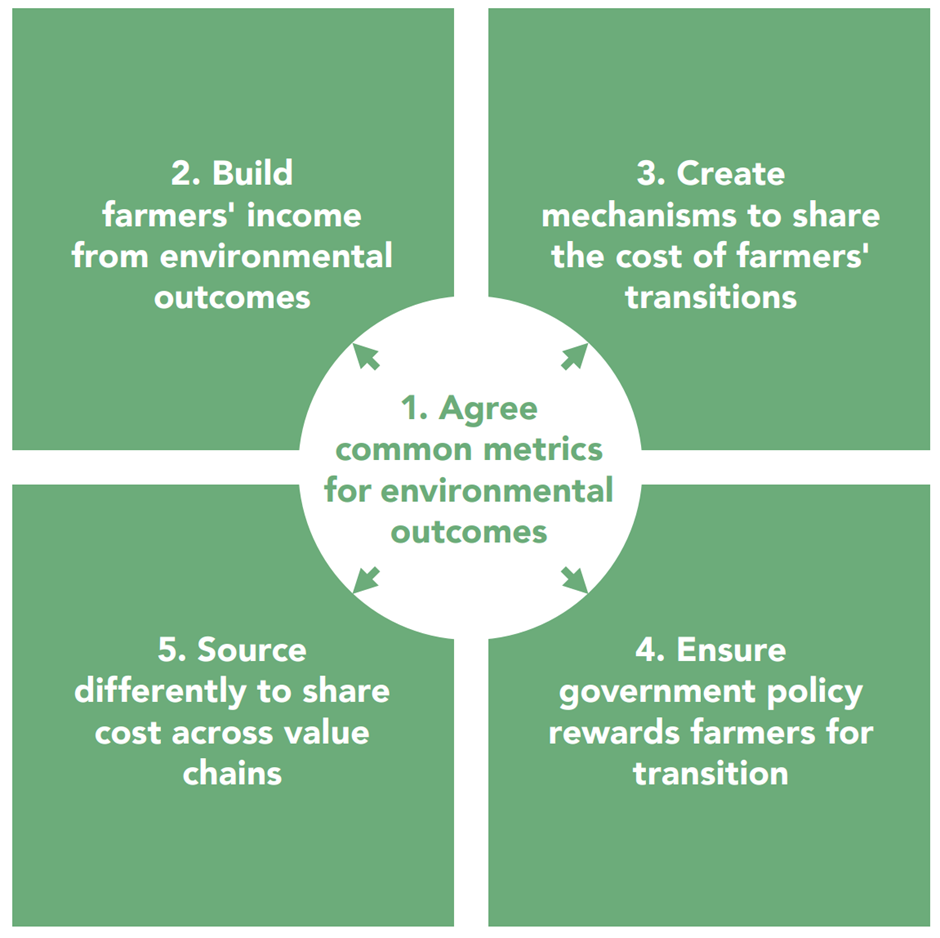

Co-authored by the CEOs of some of the major global agri-businesses (including retailers, processors and input suppliers), the SMI report identified a set of solutions needed to at least tackle the economic barrier to adoption – named “the Big 5” (detailed in the next article). These include:

- Agreement of common environmental metrics, around which additional income for farmers can be generated.

- Creating mechanisms to share the cost of farmers’ transition to regenerative agriculture

- Policy reform to reward farmers

- Sharing costs across the value chain.

It is this latter point which we’d like more detail on. Many governments are already incentivising a shift to more regenerative and sustainable solutions for farmers, and the common environmental metrics has a lot of people working on them in both the public and private sector (spoiler alert – but not quite there yet!).

Yet sharing costs across the value chain – and, crucially, being fair to farmers – is something that can and must be implemented as a matter of urgency.

At the recent World Agri-Tech Investment Forum, there was much talk of consumers not being willing to pay extra, and hence the farmers likely bearing the brunt of the transition at their own risk and cost.

Collaborative approach across the value chain

Improving collaboration (always an easy one to call for!) and a change in mindset (ditto!) are cited as ways of achieving this by the report authors, along with taking evidence-based methodologies to decisions and accepting ambiguity. There is also a call – not quite a commitment – to assign regenerative agriculture approaches across commercial and procurement teams in big corporates, not just within the sustainability teams.

The report also contains a call-to-arms of actions for different players across the value chain, from landowners, to farm advisors, retailers to input suppliers, and governments to the financial services industry.

So, everyone has the opportunity to contribute to the shift to regenerative agriculture.

But to paraphrase George Orwell’s Animal Farm, while all animals are equal, some are more equal than others. And while everyone has a part to play in the world embracing regenerative agriculture, it is clear that some have a greater part than others.

WHY REGENERATIVE FARMING IS NOT SCALING

Extract from the ‘Scaling Regenerative Farming: An action plan’ Click the link below to read the whole report.

The work showed that there are three main reasons why regenerative farming is not scaling:

- The short-term economic case is not compelling enough for the average farmer

- There is a knowledge gap in how to implement regenerative farming

- Drivers in the value chain aren’t aligned to encourage regenerative farming

WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT: THE BIG FIVE

Addressing the economic case is the most important and also the most complex challenge. We believe there are five big things we need to work on collaboratively across the whole food system to solve this problem – the Big Five. Progress on the Big Five will take time and cooperation. In the meantime, there are a number of actions companies can take to make it more attractive for farmers to transition to regenerative agriculture. These are outlined in Part 2, where you’ll also find a guide to which actions your sector should progress and how.

-

2023 Nuffield Farming Scholars Announced

The Nuffield Farming Scholarships Trust announced their newest cohort of Scholars in October, and many of their studies will be focused on topics like market challenges, soil improvement, vertical farming, cut flowers and energy production.

“Over the past 75 years, Nuffield Farming Scholars have contributed immensely to the food and farming industry, leading the way during challenging times,” says Mike Vacher, Director of the Nuffield Farming Scholarship Trust. “We have no doubt that our new Scholars will continue this tradition, offering both knowledge and leadership in their chosen topics. Coming from a range of sectors, they will investigate some of our most pertinent issues and explore new ways of meeting the future needs of the industry.

“Sharing knowledge and learnings will be more important than ever moving forward. Nuffield Farming Scholars not only become experts in their chosen topics, but leaders who are able to navigate change. This year’s Scholars have not only been chosen for the passion they hold for their topic, but also for their leadership traits and potential to shape the future of agriculture.”

Meet some of the newest cohort…

Harry Barnett, Norfolk

- Topic: ‘How to counteract the agronomic and market challenges facing UK potato growers’

- Generously supported jointly by McDonald’s UK & Ireland and Royal Norfolk Agricultural Association

Harry Barnett runs a potato growing enterprise on the Holkham Estate in North Norfolk, growing approximately 420 hectares of potatoes annually. Specialising in salad varieties for the pre-pack and export market, he has a keen interest in making the business more competitive and reducing risk. For his topic, Harry will learn how UK potato growers can counteract the agronomic and market challenges they are facing. He will focus on options for grower marketing strategies and managing potatoes as part of a regenerative agriculture system.

Luke Breedon, Wiltshire

- Topic: ‘The New Black Gold: Can Biochar help to improve agricultural efficiency, productivity and carbon sequestration in the UK?’

- Generously supported by Alan and Anne Beckett NSchs