If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

Agriweld’s low disturbance cultivation range provides numerous options to reduce tillage methods in line with modern, minimum tillage systems. Tillage reduction provides many benefits, including enhancing soil aggregation and promoting biological activity, leading to greater available soil moisture and improved soil tilth. Reducing tillage can also be economically advantageous for farmers, by minimizing passes and saving on crop establishment costs. As Agriweld design and manufacture their full product range in house, there is the opportunity to work to individual requirements.

The ASSIST & ASL – Rear mounted, low disturbance toolbars

The Assist low disturbance, rear mounted toolbar has been designed as part of the company’s low disturbance range as an option to reduce tillage processes by enabling a onepass system. Primarily designed to work with a trailed drill/ cultivator, the leading straight, serrated disc cuts through the trash creating a path for the following leg. The discs and legs lift out of work independently to the drawbar, so not to affect the drawbar height of the drill.

The Assist LD legs lift and shatter the soil across the full width of the machine, alleviating compaction in the seed bed whilst still retaining precious moisture and allowing for nutrient ingress up to 300mm deep. This toolbar is complete with rear hydraulic coupling unit complete with four double acting hydraulic services, ¾ free flow return and 7 pin plug socket. The 6m model provides the unique ability to interchange disc and leg centres, either having 12 legs at 500mm centres or 8 legs at 750mm centres for drilling maize, of which the change is easily performed with Agriweld’s own, innovative ‘hook-on’ leg socket design. The 6m machines ‘Tight Turn’ feature enables easy turning on the headland by partially folding the wings, allowing for a trailed implement to pass under the machine; operating on the same hydraulic function allows the wings to fold, in sequence, after the legs have lifted out of work. The ASL rear mounted, low disturbance toolbar performs a similar role to the Assist, however, the features provided between the two models differ to facilitate alternatives intended to cover the majority of cultivating requirements.

The 3 and 4m ASL are designed to run in conjunction with a mounted combination drill and include auto-reset legs with fixed leg centers at 500mm as standard. Available in 3m rigid, 4m rigid, 4m folding and 6m folding models, the 3m and 4m models include a PTO cut through feature for the PTO shaft to run through the frame. The 6m model includes a pair of stability wheels. All ASL models are complete with rear CAT 3 linkage for mounted/combination drills as standard.

New ASL features for 2022 include front leading discs and rear packer roller option available at the time of order or as an aftermarket feature thanks to a modified standard frame design. The popular ‘Tight Turn’ feature is also included on the 4m and 6m folding ASL; by partially folding the wings, performing operational manoeuvers on the headland is easily achievable and prevents fouling. The ASL offers an optional drawbar clevis, front leading discs and rear packer roller, enhancing the versatility of the toolbar and provides further cultivating options. Both rear toolbars provide growers with the ability to build a system that works for them to subsequently reduce their crop establishment costs.

The MIN-DIS – Low Disturbance Subsoiler

The Min-Dis Low Disturbance Subsoiler is designed to lift and alleviate compaction and promote soil structure, while causing minimum disturbance to the top layer of soil. Complete with Agriweld’s innovative Snap-Bar shear leg protection system and unique Agri-Packer roller as standard, the Agri-Packer’s replaceable shoulders with a shallow profile assist in achieving consolidation across the whole width across the machine. The company’s Easy Clean Scraper Bar system allows for quick and easy displacement of soil on scrapers and eliminates the risk of transfer of blackgrass and other volunteers to other fields. Auto-reset leg protection is also available, along with an optional flat roller with drive teeth for grassland.

The 460mm serrated straight cutting disc cuts through the top layer of the soil and trash, allowing the following low disturbance leg to pass through the soil without great disruption. Leaving the cover of trash on the field provides additional protection against water and wind erosion of the soil. The disc bar is fully height adjustable, independently from the legs.

The following LD leg combined with a standard issue low disturbance point drives through the opening left by the disc at a maximum depth of 300mm. The angled wings on the point lift the soil before it sits back down causing a shattering effect across the full width of the machine, alleviating compaction, aerating the soil and aiding water/nutrient infiltration. This is all done with minimal disturbance to the top surface of the soil.

The Min-Dis is available in 3m, 4m and 6m models.

Further details on Agriweld’s low disturbance cultivation machines and their full product range can be found on their website, via email on sales@agriweld.co.uk or by calling them on 01377 259140.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

NEW MZURI IPASS LOW DISTURBANCE DRILL SHOWCASED AT CEREALS 2022 WITH NEW LOWER

LINK SENSING DRAWBAR

British manufacturer’s Mzuri have recently launched their new low disturbance, iPass direct drill at LAMMA earlier this year which continued its public tour at Cereals in June.

Staying true to the Mzuri concept, the iPass has been designed to achieve optimum establishment at a fraction of the cost of conventional establishment, into a range of soil and residue types.

Parallel linkage coulters for accurate seeding

Low disturbance legs and clever individual parallel linkage suspended coulters allow for excellent contour following and seed depth control thanks to the drill’s independent depth wheels. Accurate seed placement is maintained across the width of the drill and excellent soil to seed contact is achieved via the V-shaped press wheel – vital for quick, even germination. The manufacturer is an advocate of band placement fertiliser below the seed for giving crops the best start, particularly useful for spring drilling where dry weather can reduce the effectiveness of broadcasted nutrition.

Large capacity, pressurised tank system The impressive machine boasts a large capacity, 5000 litre pressurised tank to accurately meter and convey high application seed rates at higher forward speeds. Four variable speed electric metering units offer high output, efficient delivery and the flexibility to shut off half of the drills width as required. Aimed at growers of a wide range of crops including cereals, oilseeds and beans the iPass is a versatile drill for those looking to minimise soil movement whilst not compromising on a quality seedbed.

New Lower Link Sensing Drawbar

The model displayed at the Cereals event featured the new semi-mounted drawbar option which has been designed to allow accurate seed depth control across the whole of the machine whilst also ensuring efficient use of the tractor and its horsepower. Automatically adjusting to ensure correct working depth, the system is useful for challenging terrain and conditions while always ensuring maximum efficiency of the tractor. The iPass range is available in widths of 4.0m, 4.8m, 6.0m, 8.0m and with two different row spacing options, excluding the 4.8m version which is only available with row spacings of 266mm. The 4.0m, 6.0m and 8.0m machines can be ordered with row spacings of either 250mm or 333mm depending on the operator’s preference.

A major draw of the new iPass is its relatively low horsepower requirement with the smallest model in the range, the iPass 412 starting at a recommendation of 170hp+, with the manufacturer recommending a forward speed of 6-18km/hr.

-

What Do You Read?

If you are like us, then you don’t know where to start when it comes to other reading apart from farming magazines.

However, there is so much information out there that can help us understand our businesses, farm better and

understand the position of non-farmers. We have listed a few more books you might find interesting, challenge the

way you currently think and help you farm better.Ecohydrology: Dynamics of Life and Water

in the Critical Zone

Ecohydrology is a fastgrowing branch of science at the interface of ecology and geophysics, studying the interaction between soil, water, vegetation, microbiome, atmosphere, climate, and human society. This textbook gathers the fundamentals of hydrology, ecology, e n v i r o n m e n t a l engineering, agronomy, and atmospheric science to provide a rigorous yet accessible description of the tools necessary for the mathematical modelling of water, energy, carbon, and nutrient transport within the soil-plant-atmosphere continuum.

By focusing on the dynamics at multiple time scales, from the diurnal scale in the soil-plant-atmospheric system, to long-term stochastic dynamics of water availability responsible for ecological patterns and environmental fluctuations, it explains the impact of hydroclimatic variability on vegetation and soil microbial systems through biogeochemical cycles and ecosystems under different socioeconomical pressures. It is aimed at advanced students, researchers and professionals in hydrology, ecology, Earth science, environmental engineering, environmental science, agronomy, and atmospheric science.

Holistic Management: A Commonsense Revolution to Restore Our Environment

Fossil fuels and livestock grazing are often targeted as major culprits behind climate change and desertification. But Allan Savory, cofounder of the Savory Institute, begs to differ. The bigger problem, he warns, is our mismanagement of resources. Livestock grazing is not the problem; it’s how we graze livestock. If we don’t change the way we approach land management, irreparable harm from climate change could continue long after we replace fossil fuels with environmentally benign energy sources.

Holistic management is a systems-thinking approach for managing resources, developed by Savory decades ago after observing the devastation of desertification in his native Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Properly managed livestock are key to restoring the world’s grassland soils, the major sink for atmospheric carbon, and minimizing the most damaging impacts on humans and the natural world.

This audiobook updates Savory’s paradigm-changing vision for reversing desertification, stemming the loss of biodiversity, eliminating fundamental causes of human impoverishment throughout the world, and climate change. Reorganized chapters make it easier for listeners to understand the framework for holistic management and the four key insights that underlie it.

This long-anticipated new edition is written for new generations of ranchers, farmers, ecological and social entrepreneurs, and development professionals working to address global environmental and social degradation. It offers new hope that a sustainable future for humankind and the world we depend on is within reach.

Ninth Revolution, The: Transforming Food Systems For Good

We are at a critical point in human history and that of the planet. In this book, a world leader in agricultural research, Professor Sayed Azam-Ali, proposes a radical transformation of our agrifood system. He argues that agriculture must be understood as part of global biodiversity and that food systems have cultural, nutritional, and social values beyond market price alone. He describes the perilous risks of relying on just four staple crops for most of our food and the consequences of our current agrifood model on human and planetary health.

In plain language for the wider public, students, researchers, and policy makers, Azam-Ali envisions the agrifood system as a global public good in which its practitioners include a new and different generation of farmers, its production systems link novel and traditional technologies, and its activities encompass landscapes, urban spaces, and controlled environments. The book concludes with a call to action in which diversification of species, systems, knowledge, cultures, and products all contribute to The Ninth Revolution that will transform food systems for good.

Plants for Soil Regeneration: An Illustrated Guide

This book is a c o m p r e h e n s i v e , beautifully illustrated colour guide to the plants which farmers, growers and gardeners can use to improve soil structure and restore fertility without the use and expense of agrichemicals. Information based on the latest research is given on how to use soil conditioning plants to avoid soil degradation, restore soil quality and help clean polluted land. There are 11 chapters: 1 to 6 cover soil health, nitrogen fixation, green manures and herbal leys, bacteria and other microorganisms, phytoremediators and soil mycorrhiza (plant-fungal symbiosis). Chapter 7 has plant illustrations, with climate range and soil types, along with their soil conditioning properties and each plant is presented with a comprehensive description opposite a detailed illustration, in full colour. Chapters 8 to 10 examine soil stabilisers, weeds and invasive plants, and hedges and trees and the final chapter, contains 5 case studies with the most recent data, followed by an appendix and glossary. The book allows the reader to identify the plants they need quickly and find the information necessary to begin implementation of soil regeneration.

-

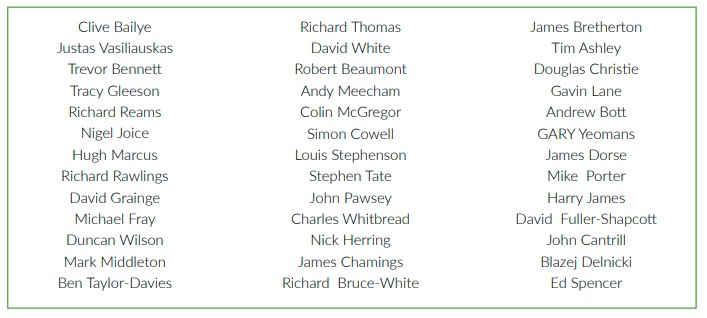

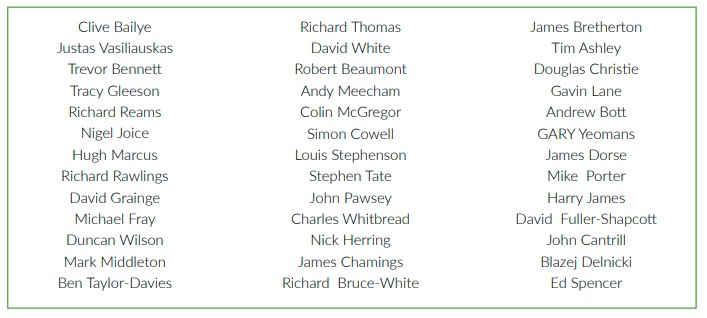

Direct Driller Patrons

Thank you to those who has signed up to be a Direct Driller Patron after the last issue. Our farmer writers are now rewarded for sharing their hard-earned knowledge and our readers have the facility to place a value upon that. The Direct Driller Patron programme gives readers the opportunity to “pay it forward” and place a value on what they get from the magazine. But only once they feel they have learned something valuable.

We urge everyone reading to consider how much value you have gained from the information in the magazine.

Has it saved you money? Inspired you to try something different? Entertained you? Helped you understand or

solve a problem? If the answer is “Yes”, please become a patron so that we can attract more new readers to the

magazine and they can in turn learn without any barriers to knowledge.Simply scan the QR code to become a patron and support the continued growth and success of the magazine.

Pay it forward and pass on the ability to read the magazine to another farmer.Clive and the rest of the Direct Driller team

Patrons

-

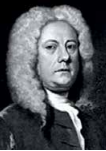

The Principles Of Tillage And What We Have Learned Since

This is a great example of how the world changes and with it our better understanding of farming methods.

Jethro Tull (1674– 1741) was an early English agricultural experimentalist whose book The New Horse Hoeing Husbandry: An Essay on the Principles of Tillage and Vegetation was published in 1731. It was the first textbook on the subject and set the standard for soil and crop management for the next century (it is now available online as part of core historical digital archives click the QR Code below). In a way, Tull’s publication was a predecessor to many other books, such as Building soils for better crops by Fred Magdoff and Harold Van Es, as it discussed manure, rotations, roots, weed control, legumes, tillage, ridges, and seeding.

Tull noticed that traditional broadcast sowing methods for cereal crops provided low germination rates and made weed control difficult. He designed a drill with a rotating grooved cylinder (now referred to as a coulter) that directed seeds to a furrow and subsequently covered them to provide good seed-soil contact. Such row seeding also allowed for mechanical cultivation of weeds, hence the title of the book. This was a historically significant invention, as seed drills and planters are now key components of conservation agriculture and building soils. But the concept of growing crops in rows is attributed to the Chinese, who used it as early as the 6th century B.C.E.

Tull believed that intensive tillage was needed not only for good seed-soil contact but also for plant nutrition, which he believed was provided by small soil particles. He grew wheat for thirteen consecutive years without adding manure; he basically accomplished this by mining the soil of nutrients that were released from repeated soil pulverization. He therefore promoted intensive tillage, which we now know has long-term negative consequences. Perhaps this was an important lesson for farmers and agronomists: Practices that may appear beneficial in the short term may turn out detrimental over long time periods. What is important is a complete understanding what you are doing on your farm and measuring all the effects of this, not just the results.

-

Thank You

As executive editor of Direct Driller I would like to extend a warm welcome to our new sponsor Trinity AgTech and its founder and executive chairman Dr Hosein Khajeh-Hosseiny. At the same time, give most sincere thanks to ProCam for their support and inspiration from the magazine’s first issue.

Procam have been great from the very start of the magazine, but there comes a time when that responsibility needs to be passed on. Their continued support of the magazine though COVID, when many were cutting their budgets was greatly appreciated. A new sponsor hadn’t been considered until we met the man behind Trinity AgTech. Quite a few people from the trade I consider friends had already gone to work there. I had wondered why this was, I figured the pay was very good. Then I met Hosein. A man with a vision who wants change. The difference with Hosein is that he believes farmers can lead the change, both for a better way of farming and to improve the environment. He talks of the “genius of the many” – the talent and innovation that lie collectively in those who care for our soils – and says he wants the software and services Trinity Natural Capital Group is bringing to market to help this along.

The aim is to “democratise access” to the best science, to self-assessment and to new markets. This’ll put farmers “in control”, he says, and ultimately better off. You don’t get this a lot in farming. Individuals that want change don’t “go far” we have been told. They are disrupters or dissenters, but we think farming needs change. When I normally get asked to meet the owner of a company, I am expecting to be told off. If you follow Clive on Twitter (or me on LinkedIn) – you will know why! This was a very different meeting. My mind went back five years to a similar discussion with the Cherry family. We were thanked for what we had done to promote sustainable farming. I was probably quiet at the meeting.

Well quiet for me. I was definitely surprised. I listened to a history, a success story and now they wanted to give farmers more options. We know from TFF that if you are happy to embrace change, that you can build a business that supports multiple members of staff and helps farmers improve the way they farm and save money. It is not a zero-sum game. A month after the meeting, I offered Trinity AgTech the sponsorship of Direct Driller as an option for their marketing. They accepted. However, you will see the Procam advert right opposite this article. We owe them thanks, they are a driving force in regen agriculture and I hope they will continue to be in the magazine for years to come.

Many won’t know the history behind Direct Driller Magazine. The idea came out of a need for more and better information about soil health. With the likes of John and Paul Cherry thinking about Groundswell we started Direct Driller. Getting anything started from nothing is difficult. We knew that TCS in France and No-Till Farmer in the USA were both successful publications. There was no reason why a UK publication couldn’t be just as successful. But making it a reality is a big step. First, we asked farmers if they would like such a magazine. The answer was “yes”. Over 800 of you subscribed to a magazine that didn’t exist. Secondly, we found content for a magazine. The third part of producing a magazine is funding it. We never wanted to charge farmers, we wanted knowledge exchange to be free and open. Not only as an on-line publication, but as a hard copy magazine which includes the cost of postage.

This is where is gets tricky. It’s very hard to get advertisers to see the value in a new magazine. Things changed when I met Richard Harding from Procam. Richard was sat in John Cherry’s kitchen working out how we were going to get farmers and advertisers at Groundswell. Richard was a font of knowledge – inside I was thinking he would make a much better editor than me. Richard introduced me to Garth Bretherton, then Regional Director at Procam. Procam wanted to be seen as the forerunner of this regen ag space. I put a deal to Procam, where they could be the “sponsor” of the magazine.

They accepted and with five other advertisers we had enough revenue to get the first issue printed and mailed. But more than this, Procam lent us some of Richard’s time and expertise to help find content for the magazine. Richard is as much a part of the magazine as Clive or I am. With free labour, from Richard, myself, Clive and a barter agreement with Mike Donovan who back in 1992 started and built up Practical Farm Ideas, we had the team to get the first issue put together. While many not quite of appreciated the contribution of Procam in those early days of the magazine, they were critical to it’s launch. Everyone involved with Direct Driller looks forward to an equally stimulating and useful relationship going forward, which comes at a propitious time in farming. There will be many changes and developments in farming over the next ten years and all will involve the need for both honest explanation and educated discussion. Our new sponsor takes us into an exciting time.

Chris Fellows, Direct Driller magazine

-

The Media We Consume

CHRIS FELLOWS

We are becoming increasing divided by the type of media we consume. We see this on Twitter, The Farming Forum, LinkedIn and Facebook. Everyone tends to read sites and articles that reflect their own views. Reinforcing what they already think, the way they evaluate problems and how they react. This is often referred to as the farming echo chamber.

This means that often we have no idea what other people think and disregard them as outliers to the way we think. The internet has most certainly made this worse, Facebook encourage it. We need to integrate and share knowledge more. Knowledge needs to be more democratic. It shouldn’t matter where it comes from. Farmers need to be shown both sides to an argument and be allowed to choose the path that is then right for them. At the moment content is dictated by too few sources. There are around 800 websites around farming that have knowledge on them. How many do you read a week or even a year?

How do we change this?

No one wants to read they are wrong; no one wants to face their failings. It’s tough to accept, but mistakes are a part of life. You should just be able to say, “that was a bit stupid” and apologise if necessary.

I have always said what I think. But then my career does not depend on being part of a structure. I can set my own structure. It is, however, important to know why you are taking a position and be able to back it up by facts. It should not just be based on the position of the institution you are part of. You and only you are responsible for what you believe and the arguments you choose to put forward.

You are free to change that opinion as more facts are presented. You should constantly be in a state of selfreflection. Objective truth exists, we should be questioning whether we are making a conscious choice to adhere only to information that does not challenge our position. Be aware of your own confirmation bias.

The easiest way to do this is to read more and from more sources. Expand your horizons, it may not change your view every time, but knowledge and understanding breeds sustainability in businesses. Get out there and read!

-

Featured Farmer – Philip Bradshaw

I farm in partnership with my wife Jayne, in the Cambridgeshire Fens near Peterborough. We started farming together in 1989 when I left the family farm having gained our first tenancy on an 33ha County Council Farm. It is staggering to think that we equipped the farm for less than £10000, including a 15-yearold combine for £1500, but with both of us also doing some off farm work we had a couple of happy years there. Over the years we have moved farm twice to gain larger tenancies, inherited my father’s share of the family farm, and bought a bit more land along the way. Our 2 sons have good careers outside of agriculture, but they will still occasionally roll their sleeves up and help at harvest. We now farm 220 ha of mainly skirt fen land in 3 blocks around Peterborough, 30% owned and 70% rented. Because of the distance between the blocks, the smaller two parcels to the north are ran with a collaborator/contractor doing much of the work, with some direct drilling, while our main farm at Whittlesey is worked by myself with a fleet of largely ‘classic’ machinery on a ‘Conservation Ag’ basis.

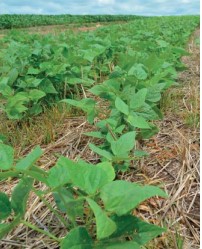

We share farmed extra land for a while, and grew potatoes and sugar beet for many years, but dropped potatoes around 10 years ago. At this point we largely stopped ploughing and started on a system of shallow tillage using a Vaderstad Carrier, with subsoiling as required. I didn’t realise at the time, but this was a good way of preparing our soils for the move to no tillage. The system worked well, and we managed to keep blackgrass at a modest level on most of the land, while also growing consistently good yields of cereals and sugar beet. We started investigating ‘Direct Drilling’ some years ago, visiting a few people already not tilling and we also tried a few drills. One of my collaborative colleagues bought a Weaving Big Disc drill, and from around 2014 we started establishing some crops with it, and our sugar beet and OSR using a Sly Strip Cat system.

Having gained confidence in the process, we decided to acquire our own no till drill, and considered the options of buying second hand or new. Unfortunately, with a modest acreage, and the shortage of second hand no till drills on the market it was a challenge to find such a machine. Happily, help was at hand, and we were fortunate to gain funding from the Fens LEADER group project which was part of the Rural Development Programme (RDPE). LEADER had various aims and objectives, including modernising and improving sustainability, and encouraging strategies to protect soils, and reduce Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. On this basis I decided to try an application for LEADER funding. The bureaucracy involved was daunting, but after a very comprehensive application procedure we were eventually awarded a grant of over £13500 which we used to acquire a new British built Weaving GD 3m disc coulter direct drill which arrived in July 2016.

I believe we were possibly the first LEADER funded drill in the country, and we had to sign up for some interesting projected outcomes including cost savings, fuel savings, reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and sharing knowledge. The new drill arrived just in time for our annual farm open day in 2016, and the 50 or so visiting farmers here primarily to look at KWS wheat varieties could also look at the shiny new drill and discuss our planned strategy. This started the ‘No-Till in the Fens’ project of knowledge transfer that was a condition of our grant.

I knew then that I would have liked two drills, one tine, and one disc, but could only afford one, and plumped for disc. I believe the GD was a good choice but regret not going for a larger trailed one. We bought a second-hand front tyre press to go on the front linkage to consolidate our sometimes fluffy lighter soils, and also counter the weight of the mounted drill. We had identified with our earlier no till experience, that the headlands and some sidelands of fields were slightly compacted due to turning of machinery, so we also bought a 40 year old Howard Paraplow for £600 to cheaply alleviate headland issues.

I set off drilling straight into stubbles, including fresh lifted beet land, and the GD was very impressive. We applied slug pellets with the drill after OSR and this proved to be very wise. We put some cover crops in and drilled straight into them in the spring. Harvest 2017 was nervously anticipated, with 95% of our crops direct drilled, but except for some heavy land beans, yields were right up with our 5-year average, with considerably reduced costs. Our small area of heavy land we realised needed easing gradually into the no till system… In autumn 2017 we had the dubious privilege of being selected for a post LEADER grant inspection by the RPA. This caused some fresh challenges; as part of the application claimed some positive outputs involving cost savings, fuel savings, reducing GHG emissions and sharing knowledge as mentioned earlier.

Analysis of accounts and other data allowed us to show we had surpassed the fuel and cost savings, and the success of our open days and other events had ticked the box for knowledge transfer, with 180 stakeholders engaged. The GHG emissions initially looked difficult, but the internet was my friend, and I found some conversion factors to show that the fuel saving alone also translated to a GHG saving that more than hit our target.

We have since gained the confidence to sell our plough and cultivation equipment, and pursue a strategy of no till establishment, with some occasional loosening of soil as deemed necessary. Interestingly, our yield maps showed that our paraplowed headlands now sometimes yielded slightly better than the field middles, which means we are not afraid of paraplowing a whole field should it be necessary, but we hope the need for this will diminish.

This system has worked well, with yields maintained, and over the years we started to learn more about a ‘Conservation Ag’ approach that went further than simply not tilling land. While we have found many sources of knowledge useful on our path, including this magazine, and the excellent organisation that is BASE, we have also been fortunate in gaining first-hand advice from other sources. Our agronomist Rob Wilkinson of Strutt and Parker, has been very supportive of the system, and also brought Ian Robertson of Sustainable Soil Management along to help refine our strategies on soil management, and the use of biologicals etc. We are also fortunate to have regular visits from Philip Wright of Wright Resolutions, partly as a consultant to advise, and partly to conduct some joint on-farm trials including tyre pressure trials, soil loosening and biological soil management effects.

We now have refined our system and work on a few agreed principles. We have added a second-hand 2013 Weaving Sabretine drill to our modest fleet, and I overhauled and upgraded it last year. We also have still the GD which is now in it’s 6th season and has recently had new closing wheels/tyres and some new bearings. Both drills and our 5 leg paraplow have liquid fertiliser/ amendment kits fitted using components sourced from SK Sprayers Ltd, and all are fed from a front tank that I made up using a second hand Knight front sprayer tank. An old, trailed press is used to consolidate paraplowed land, and a set of heavy rolls with hydraulic paddles are used post drilling if needed, and also as a ‘Straw Rake’ on occasion. We sell most of our straw, but use some of the proceeds to buy and establish multi species cover crops. I prefer to keep growing roots in the soil when possible, but we do rotationally return some straw as well. The recent wet years have caused some issues with compaction from the weight of rain, and washing down of fine soil particles, so we actually paraplowed a lot of land in autumn 2021 to alleviate this.

We aim to use the Sabretine drill to establish cover crops, OSR and some beans, and the GD for everything else, but this strategy does vary. We have also attempted to establish a clover crop ahead of spring beans to hopefully keep as a living mulch, but it may not be quite good enough due to the lack of moisture at establishment. Because I do some off farm work, and we manage some on farm trials here, we can justify some slight over capacity in machinery, and have our own combine, and also a 20 year old self propelled sprayer. Some collaborative/contractor work is done on some of our more distant land.

Our rotation is variable, but typically is wheat, second wheat or winter barley, OSR/oats, wheat, beans. With use of a good catch crop for a few weeks between the wheats, and some biological help for the soil and plants, we can now grow a second wheat that will yield virtually as much as a first wheat. Unfortunately, we have very little storage facilities on farm, so our cropping choice is sometimes affected by logistical issues, and we occasionally grow peas. (Sugar Beet was dropped a few years ago due to the low contract prices offered. It worked well with strip tilling).

We are looking to add biologicals with the drills rather than liquid fertiliser, but this is work in progress. We haven’t really applied any P&K from a bag or lime for over 7 years now, and field indices and pH appear to be either stable or improving. I still wonder if we could be very slowly mining our soils of nutrients, but the strategy seems to be improving soils rather than depleting them, and we have at least 5 species of worms in increasing numbers. We cut back carefully on Nitrogen last year by about 25%, and hope to cut back more this year, while also maintaining crop output.

We don’t currently have any above ground livestock on the farm, but this may change in the future, with maybe some managed strip grazing of cover crops with sheep. We do not currently have a controlled traffic system in place, but do take great care to avoid soil damage. Grain trailers are kept to the headlands at Whittlesey, and tyres are ran at low pressures when possible. Some trials work here has shown the importance of tyre pressures on the drill tractor, and we run Bridgestone VF tyres down to around 0.65 bar pressure. All the farms are in an HLS/ELS agreement that we are currently rolling over on an annual basis. This takes out some of our poorer land, and a good mix of options has improved our environmental profile. We have some diversification with some storage under licence on one farm, and I also do some occasional consultancy work on Farm Management issues.

We are enjoying our journey into ‘Conservation Ag’ and learning a huge amount as we go along. The time saved in establishing crops has allowed us to improve our work/life balance further, and the change in approach is now showing us a sustainable way forward as we look to reduce further our reliance on artificial inputs as our soils and crops improve. There are challenges ahead with recent substantial rent increases on the Whittlesey farm, storage issues, input costs rising and potential lack of availability. However, our crops and soils are looking well as we enter Spring, and we wouldn’t farm if we were not optimists!

-

Pioneering Direct Drilling – 1965 TO 1993

Written by Dave Ablett.

I started direct drilling in 1965, and for 21 years was at the front end of spreading the word. I started on machine design and manufacture and was responsible for the first commercially produced and sold seeding machines in the UK in 1967 and in Brazil in 1973. In those early days direct drilling was mainly promoted by the desire of chemical companies to promote sales of herbicides. I was employed by ICI ( under its various names!) and all my design and development work was given to machinery manufacturers free of charge. In those early days considerable problems were encountered because of the lack of follow up herbicides. My main design and development work was done in co-operation with Howard Rotavator Company in the UK and their Brazilian associate company FNI. In those early days the size of a seeding machine was restricted due to the size and hydraulic capacity of tractors.

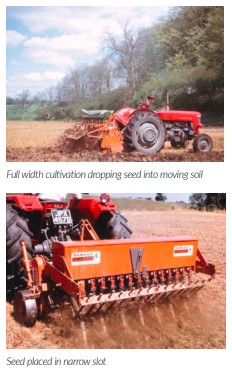

The first direct drill I was involved with was the “Fernhurst coulter system” on a Massey standard seed drill. It proved to be an efficient rake when working where there was surface trash.

As a result of these trash problems it was thought that a powered slot cutting system would cope better with any crop residues. The first “Rotaseeder” had normal rotavator blades and moved all the soil. In reality the seed only needed to be introduced into the soil with the least soil disturbance possible so the blades were cut down to provide a narrow slot. Moving from complete width rotavating to narrow slot cultivation with coulters placing seed into the slot was a major step forward in maintaining crop residues on the soil surface. The Rotaseeder was mainly intended for grassland renewal, kale seeding and cereals.

Development field work was carried out throughout Europe. A major demonstration tour through France, Germany, Spain, Holland and Denmark was done in 1966 to get farmer opinion on system.

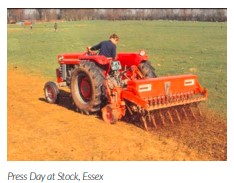

The final design was launched to the press in 1967 on a farm in Essex. Because of my involvement in design and development Howard Rotavator Company asked me to operate the machine for the launch..

In 1967 the main problem faced by the Rotaseeder was that cutting blade wear was too severe when seeding stony or sandy soils. Also rate of work was slow compared to conventional cultivation seeding machines. Not needing to plough or carry out further tillage operations were not taken in to account when farmers were under pressure to get the seed in the soil. The Fernhurst coulter and triple disc systems left open slots which were an ideal habitat for slugs. The Rotaseeder did not suffer slug problems to the same extent. As a small side diversion I encouraged Howard Rotavator Company to build a trailed machine capable of putting fertiliser on with the seed. It had to be a trailed machine because tractor three point linkage was not strong enough too lift a double hopper machine. I did a little work with it but Howard’s development engineers were too busy involved in big balers and rotary muck spreaders.

Rotaseeders were produced by both Howard Rotavator Company and WMF, their main use in later years was for grassland renewal. Indeed until a few years ago a machine was being used in Wales to stitch in grass seed after a silage cut. No herbicides needed! Kale was a popular crop with dairy farmers but they had serious poaching problems when grazing a conventionally seeded crop. I designed and developed a simple “kale coulter” to put seed into a simple slot with minimum soil disturbance thereby maintaining a firm surface when grazing. The slot producing coulter was a modified injection tine with a simple brush feed seed mechanism. I went on secondment to Brazil and my successors in the UK got Gibbs of Ripley to make a complete simple machine available. A new team of engineers were taken on by the Machinery Section to work on direct drilling coulter systems and and I moved on to design and development of specialised spray attachments to apply Gramoxone for weed control along the row of plants in orchards and vineyards mainly in Eastern Europe..

In February 1972 I was seconded to Brazil, mainly to develop sprayers for weed control in coffee and citrus. I was also heavily involved in the Direct Drilling campaign. Mid August 1972 I was asked to visit a farmer in Parana State to advise on direct drilling soya beans. The farmer had visited me at ICI when he was on a visit to family in Germany. On his farm in Parana he had made a copy of the first prototype UK Rotaseeder. He was using full size rotavator blades cultivating the whole area.

Parana and the other two southern states of Brazil are hilly and all planting was done following contours. Double cropping of wheat followed by soya beans was the standard farming practice. Also heavy rains at soya planting time – late August onwards – gave serious problems of soil erosion. This washed the standard incorporated herbicide down hill and into the water systems and rivers. The terra roxa soil had no stones and made soil moving seeding machines less prone to wear.

I immediately went to FNI ( Fabrica Nacional de Implementos) who were Howard Rotavator Company in Brazil and suggested we should make a mounted direct drill capable of seeding both soya beans and wheat for use on contour farming system areas of southern Brazil. ICI were in the process of setting up two development teams to promote direct drilling. One based in Parana and the other in Rio Grande do Sul with the principle aim of promoting herbicide sales. They had initially planned to use direct drills imported from the UK but my provision of locally made Rotacaster’s solved their seeding problems.

My design of a new coulter system was rapidly taken up by FNI. Because disturbed soil could dry out the coulter placed the seed at the bottom of the narrow slot and a following press wheel gave excellent seed to moist soil contact. Tractors were getting bigger but still good manoeuvrability in the contoured fields was imperative. This seed placement system consistently gave the best germination performance when compared with others including conventional methods. Direct drilling was called “Plantio Direto” in Brazil and I had helped the Parana development team make an audio visual of the system.

The FNI Rotacaster was launched at the 1973 Sao Paulo state fair. I believe some 80 to 100 machines were made and sold during the few years it was in production. ( Unfortunately FNI followed its parent Howard Rotavator Company into liquidation).

ICI UK had sent a triple disc coulter equipped machine to the team in Parana. It could not cope with soya bean seeds. The double discs both crushed and broke the seed skin and also gave erratic seeding depths. Often on the surface of the slot. I designed an improved “kale coulter” so that the team could use the seeder as a test unit for herbicide application systems. Also Jaime Ozi, president of FNI, had imported a Bettinson triple disc machine with a view to manufacture in Brazil. This had the same problems when seeding soya beans so I made a similar “kale coulter” design for him. My coulter design was to replace the triple disc. The depth wheel which was adjustable to control depth of slot also gave good seed to soil contact to optimise moisture availability.

Other planting machine manufacturers were only half heartedly interested in direct drilling.

in the southern states because their machines were planters and not suitable for wheat seeding. Main problem stopping uptake of direct drilling during the early/mid seventies was the lack of over the top herbicides to aid weed control during the growth of the soya before a canopy could be formed. If there was poor wheat stubble cover then a few weeks after seeding weeds could take over! I designed many tractor mounted machines with a view to applying herbicide along the row. None were produced because a fortunate development, coinciding with my return to UK, was the availability of selective herbicides.

Back in the UK with Alan Bloomfields team from 1976 – machinery technical service and visitors, and specialised Gramoxone application equipment including demonstrations of my citrus machine mounted on a Landrover in north Africa. I was sent on secondment to Argentina in 1978 and moved from machinery design and development to herbicide systems management. Several suitable direct drilling planters were being made suitable for handling soya beans on the flat pampas. I set up a “specialist” team of distributor/ agronomists to promote “Siembra Direto” – local term for direct drilling. I also organised an Argentine conference on direct drilling held in Rosario and sponsored by Duperial the ICI local agents. I produced herbicide tank mix recommendations to improve weed control and an audio visual system for use by the distributors. I also gave a couple of thirty minute technical TV shows on Siembra Direto.

After Argentina I almost immediately went on secondment as Techno/ Commercial manager to Nigeria. Included electrodyn work in cowpeas in cooperation with IITA plant breeders and also writing the users operating handbook/leaflet.

Back to minimal cultivation and maintaining surface crop residues I was sent to Canada in 1984 to put some sense in to chemical fallow. For years ICI had been promoting the use of a herbicide to control weeds during the fallow year of the Canadian prairie wheat producing system. It was clearly apparent that low wheat yields could not support high cost of herbicide so I finally killed the project. I did actively promote the system of minimal cultivations for winter wheat following the introduction of improved winter wheat varieties. This kept the stubble on top and prevented soil erosion by wind. In the prairies there are 400 kms of wind per day! Following on from Canada in 1975 I was seconded to ICI Americas and based in the mid west -Kentucky. Not involved in machine design, as there were many no till planters available for direct drilling. ICI contact herbicide Gramoxone had been sold by Chevron in the USA and it was being taken back in house by ICI Americas.

My project was to develop the best tank mixes recommendations and train the ICI Americas local staff in how the herbicides and systems work. I had development sites from St Louis , Missouri across to Delaware and down to Tennessee. Some six sites in all. In September 1986 I left ICI before completing the secondment and was headhunted to run the Cooper, Pegler sprayer company. In 1989 I took on a Hill farm in Wales and in the third year I was loosely involved in direct drilling! Having a suckler cow and sheep enterprise I was making silage. Perusing the local farming press I found a 4 metre Moore Uni drill for sale cheap. I bought it and a local engineer helped me cut it down to two and a half metre width which meant I could get down the narrow Welsh lanes and stitch grass seed into silage stubble for my neighbouring farmers. Stitching in and then applying slurry gave excellent establishment results.

Now retired and reminiscing I realise I was actively involved in Direct Drilling on and off for over 30 years and still maintain an active interest in Direct Drilling and |No-Til worldwide.

NB at a machinery exhibition in Rio Grande do Sul in 2007 the FNI Rotacaster was exhibited at the entrance to the show as the “PIONEER” of direct drilling in Brazil.

-

Healthy Soil – Healthy Plants

Originally Printed in Terra Horch – Issue 22-2021

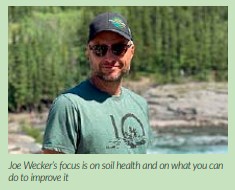

Joe Wecker runs a 9,000-acres farm in Canada. He does not only work according to the principles of organic farming,

but also uses companion crops and inter-crops and improves soil health by applying plant auxiliaries. He talked to

terraHORSCH about his experiences.

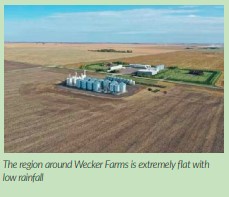

Companion crops and inter-crops, auxiliaries, soil health and a varied rotation – these were the topics Joel Williams, an independent plant and soil health educator, wrote about in the last two issues of terraHORSCH. Joe Wecker, a farmer with German roots from Regina Plains in the southeast of the province Saskatchewan, Canada, uses these principles in practice. The family farm which he runs together with his father and two permanent employees is situated between Winnipeg and Calgary just over 100 km north of the US American border. The region is extremely flat, there are no windbreaks. The average annual rainfall amounts to 380 mm, though in the past four years there was significantly less rain – a total of 50 mm per year. However, this season it finally rained some more. Winters in Regina Plains are very cold, the summers are warm.

Wecker Farms are located on a main road. On the one side there are two residential buildings as well as the farm buildings including an impressive silo installation with drying and cleaning. More about why the latter is important later. Only some metres away on the other side of the road are further silos. The farm and the inventory are very well kept. Tractors and combines mainly are from John Deere. The farm uses a 9560 RT, a 8370 RT, a 6215 R as well as a Fendt 1050 Vario, two combines with 14m cutter bar and two swathers with 12 m working width. They sow with an 18m machine with liquid fertiliser system. Moreover, they use a fine cultivator for tillage in spring, harrows and hoes as well as a roller-type harrow. The harvest is transported from the combine with an auger wagon and from the field boundaries with three trailer trucks.

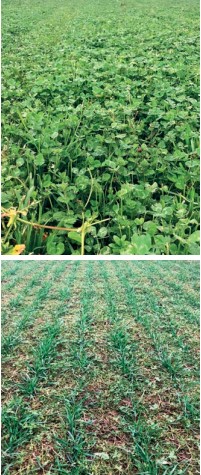

They farm more than 3,500 ha, 2,500 organically, the remainder is in transition to organic farming. “But everything is farmed in a nutritional farming system“, Joe Wecker says. This is why the farmer considers his machine park to be rather large. In his opinion, nutritional farming on the one hand means diversity of crops, cover crops, inter-crops and green manure. Moreover, he relies on the specific use of plant auxiliaries. He grows: durum, HRS wheat, oats, flax, alfalfa seed, khorasan wheat, spelt, emmer, peas, lentils and chickpeas. He flexibly uses different companion crops depending on the rotation. For example: cereals/cereals-clover, cereals-alfalfa, chickpeas-flax, peamustard, pea-oats or barley, lentiloats, lentil-brassica as well as brassicapea-clover.

Less risk

But why does he do this? “Intercropping, i.e. the cultivation of companion crops and inter-crops, means more bio diversity”, the farmer is convinced. “The result are very positive consequences for soil fertility, for beneficial insects, for the encouragement of mykorrhiza and for nutrient exchange – this is particularly apparent for peas as a companion crop, as well as for a synergistic growth. There is no competition, less fertility inputs are needed. There are higher residues for ground cover, less weeds and harvest residues decompose faster. And: risk reduction, especially in very dry years.

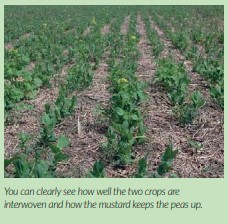

My experiences for example with oats in combination with peas were very good. Their root structure and its function, too, are completely different. There are different pH values in the different areas and nutrients, too, are released differently. If you dig up the plants, you can perfectly see the rhizobia that fix the nitrogen. Another example is the combination of brassica and maple peas. We grow them together because the peas often get lodged before the harvest. But the brassica supports them so there are hardly any problems when threshing. It works excellently. For maple peas really are rather difficult to grow. Thus, we get a high price for them, and brassica is a great help“, the farmer explains.

For organic flax with chickpeas. “We cultivated these crops two years in a row”, Joe Wecker says. “Normally chickpeas have to be treated with fungicides five to six times. But being a certified organic farm that’s no option for us. With the combination we had the experience that we don’t need any fungicides at all. There are some processes, probably in the soil, which make them unnecessary. You can clearly see it.

Another combination we like to use is organic Eurasian wheat with clover as an under sown crop. I attach major importance to one thing: For me, intercropping does not only mean to grow mixed crops where both partners are used. In my opinion, it also includes companion crops where only one crop from the combination is harvested. I like to use this for cereals, for example for oats and peas. This actually is one of my most favourite combinations. It is always striking how healthy the leaves are. Another example is oats with marrowfat peas. The latter poses quite some challenges for the farmer. In combination with oats it is much easier. Especially the weed pressure is lower.“

Positive effects

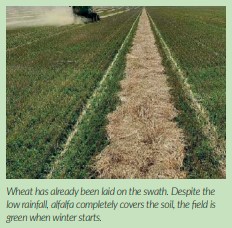

Joe Wecker describes another possibility: HRS with alfalfa as an under sown crop. Especially when producing alfalfa seed there again and again are volunteer plants in the following years. Although, in this case, he specifically uses them as a companion crop, he has to see to it that the alfalfa share does not get too high. The cereals then have a better chance to pass the alfalfa. The positive effect Joe Wecker noticed are 1.5 to 2 % more protein in the wheat. And all that without any yield losses. Using an underseed with alfalfa, thus, is ideal if you want to achieve an increased protein content for wheat. According to his experience, brassica with maple peas also work very well together. Threshing can be carried out without any problems by simply changing a few settings at the machine.

According to Joe Wecker you immediately see the effects of intercropping. Right in the first year he did no longer have to use any fungicides for the combinations flaxchickpeas and flax lentils. With regard to soil health, it takes a little longer. Over a period of three years, step by step we reduced the fertilising intensity and now the quantity is only half as high compared to the time he started. During this time the biological activity of the soil improved – with stable yields. The plants in total, benefit from not being filled up with nitrogen to such an extent. The pressure of fungi and animal pests decreases significantly.

Joe Wecker attaches great importance to soil and nutrient analysis. “I focus on the correlation of what is in the soil and what is in the plant”, he says. “Or rather what is in the soil and what is not in the plant.” For you cannot take it for granted that everything from the soil is available to the plant. You need an intact biological activity of the soil. This is why we do not only carry out soil analysis, but also tissue test of the plants. If we notice any peculiarities, we know that we have to do something for a good biological activity of the soil. In addition to our inter-crops and companion crops which also have a positive effect on it.

No matter if organic or conventional – we apply stimulants on all our fields to encourage the activity of the soil especially in the root area. It thus gets a boost so that the plant can dispose of some nutrients that so far have not been available.”

Regular analysis

At Wecker Farms, the tissue tests are carried out at least once a year. Joe Wecker compares them to the soil analysis and if he notices that nutrients are not available to the plant he spreads them. It usually is boron that is applied together with kelp and fulvic acid. It is not expensive. And it does not do any damage, Joe Wecker says. But he achieves this little boost for the soil activity.

But back to the soil and plant analysis. Joe Wecker describes the results of an analysis of the fields that are still farmed conventionally. “The crop is flax. I did not apply any phosphor. The analysis showed only half as much nitrogen as there actually should be. But I did not worry about that at all. And the population really develops excellently. Before our objective always was how to achieve the highest possible yield with a high effort. Today we do the opposite: we focus on how little effort is necessary to not lose yields. During the vegetation period we always have the refractometer at hand. We, thus, can find out very quickly on site how healthy the plants are. By means of the sugar content we notice if there are any shortcomings. If so, we immediately carry out a laboratory test to get exact data. If for example we apply boron, we mix in fulvic acid, kelp and a little bit of sugar. Sugar is good for beneficial organisms.“

You cannot take it for granted that everything from the soil is available to the plant. You need an intact biological activity of the soil.

Consequent action

The conversion of the farm to organic farming started five years ago. Asked about his reasons the farmer answers: “On the one hand, we ourselves have been eating organic food for quite some time. On the other hand, we noticed soil degradations on the farm. This is why we started to think about intercropping. We also questioned a lot and tried to detect correlations. You often do not notice small things until the problems get bigger. And then you start to think. With regard to the yields, the losses are really minimal compared to my neighbours. However, it depends on the crop. For barley and flax for example it is hardly noticeable, for wheat we talk about 10 to 15 %. In this case it is very important which variety you chose: Modern wheat only achieves good yields if the nutrient supply is optimum. Therefore, we prefer older varieties which usually are still on the market. If not there often are some remaining stocks. Barley in turn is less sensitive according to our experience.

But yields are not everything. I often discuss with the mills I supply directly. This is the reason why the cereals are thoroughly cleaned and dried. My customers often tell me: We love your cereals. Our bread tastes a lot better with it. As I already said before: In the future, our customers will no longer only pay for the quantity, but also for other things. For example chickpeas grown with zero fungicides.

I wanted to farm in a regenerativeorganic way for quite some time. My focus has always been on soil health and especially on what we can do to improve it. This is behind everything we do. For a healthy soil guarantees healthy plants. The same is true for insects. We attach major importance to that the fact that our fields provide a good living environment for bees and other beneficial organisms. In this respect, intercropping is ideal, for we automatically create areas where insects can thrive in an optimum way. And it”.last but not least, I am convinced that our customers expect more from us than just always going on like before. This will not only be an important reason for them to cooperate with us. They will also reward it”.

-

Farmer Focus – Ed Reynolds

At the beginning of February I was fortunate enough to attend the 2022 BASE-UK AGM. There were many excellent presentations, including the lecture from Dr Sam Cook on conservation biological control where she referred to the three P’s – Predation, Parasitism and Pathogens. It got me thinking about the next level of IMP that we have the opportunity to follow. At the same time as using less insecticides and more funding for habitat under mid-tier and ELMS schemes, identifying beneficial species and making decisions made on insect numbers (trapping) and crop risk is surely the direction we should work towards.

The one presentation that stood out was Professor Richard Bardgett’s session on soil fauna and its relationship with diversity of plant species. He talked about how ‘diversity of plants cultivate the soil micro-biome’ and the significance of this regarding complete functionality of the soil (including organic matter breakdown, physical structure and nutrient availability through the ‘microbial loop’).

Professor Bardgett suggested degraded arable soils can potentially be turned around in 2-3 years with this approach. Unfortunately, most of the cash crops we currently grow are monocultures, but there is great opportunity for plant diversity in catch and cover crops. A problem we have is a workload peak at harvest, at the time when cover crop establishment should ideally occur. Understanding that getting them in early is key, we are experimenting with a faster way to establish cover crops very soon after harvest. We have mounted a Techneat Avacast onto our Claydon straw harrow, with the hope to establish the cover crop and get the benefit of the straw harrow ‘cultivation’ effect on crop residue breakdown and slug egg destruction. The air seeder unit has several different metering cartridges to cope with the variation in seed shape, size and density. I see growing cover crops as an investment in our soils, and will endeavour to do this between every cash crop, if we have 6-8 week gap. A species mix with a diversity of physical root structure will be our aim.

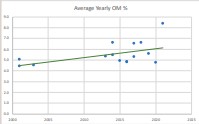

Another winter project we have just embarked on involves taking soil organic carbon (SOC) measurements to get a handle on where we are, and to establish a baseline. I have been told, from people more knowledgeable than me, that this is a good idea for the future and allows you to track the effects of regenerative farming practices on your soil. We have started with one 24 ha field. We split the field into 5 zones according to soil texture and used two different sample depths. We have taken a GPS coordinate of each soil core, to allow repeatability every 5 – 10 years (with the help of CA Agricultural Services). We are using a measurement that includes organic and inorganic carbon, bulk density (to calculate quantity) and active carbon to see what is available to soil microbes. In the past, I have been sceptical of soil organic matter results (around 5.6%) on our high calcium soils, as artificially high. I hope these tests now available to the industry are more representative, and my method of sampling stands up to scrutiny over time.

As winter gives way to spring, the flying flock of sheep move on. They have been with us for the winter months, grazing our cover crops. This is the second year we have done this, and I would like to thank Ed Hartop (sheep grazier) for his diligence in moving them round according to our soil management plan. It struck me that the farm as a whole is better-off because of his presence with us, even though it is fleeting. Ed has a great knowledge of agriculture, which is different yet complementary to mine. We take a collaborative approach to problems and put plans into operation that are more likely to succeed. I hope to see more grazing animals on the farm by including 2 year species rich leys in the rotation and possibly grazing wheat in the future. This is just one example of more people being on our farm in general, since we followed a more regenerative ag path. I am all for that.

-

Plant Sap Analysis: What It Is, How To Do It And Why

Maintaining plant health to reduce inputs is a key goal for many regenerative systems. In this series of articles

Mike Abram explores how plant sap analysis could help deliver this

Much like with our own health a balanced diet is important for maintaining health and ultimately maximising yield and quality of crop plants. Some of the macro- and micronutrients the plant takes up are used to power photosynthesis – energy production in the plant – while others facilitate the conversion of the sugars produced by photosynthesis into a whole range of other plant compounds. These include defence materials, such as anti-feedants, cell strengtheners, physical barriers, and root exudates to recruit microbial communities to help protect plants from attack. To build these defences nutrients are needed in various quantities ranging from kilograms of macronutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium to grams of micronutrients like copper and zinc.

A deficiency or excess of any of these can limit photosynthesis and / or these other plant compounds, including both passive and active defences. But understanding whether a plant is receiving a balanced diet of nutrition is no easy matter. Soil nutrient analysis gives a picture of what is present in the soil at that point, but not necessarily what is available to the plant to take up. Plant tissue (dry matter) tests during the growing season are another potential source of information. These measure all the mineral nutrients stored in the sampled leaf, and are particularly helpful for understanding the success of nutrient applications at the end of the season. But again, it doesn’t just measure what is available to the plant at the testing point, as it also measures the nutrients stored in the leaf, which are much less available to be used for plant development.

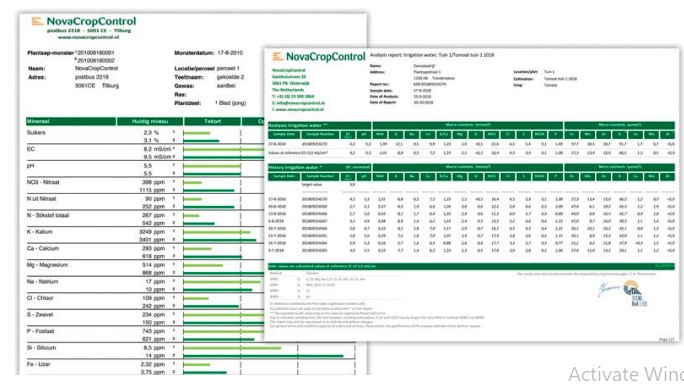

Wanting to determine just the nutrient fraction that was available for plant development was the starting point for the development of plant sap analysis by Dutch company NovaCropControl back in 2009. Its sap analysis service provides, what it says, is a more accurate way of measuring the nutrients available to the plant at the time of sampling. The advantage of only measuring what’s available to the plant is that it shows up potential deficiencies earlier – perhaps one to two weeks earlier – than tissue analysis, says Eric Hegger, a consultant with NovaCropControl. “In a tissue test a big part of what is being measured are the stored nutrients in the leaf, which cannot be used any longer,” he explains. The test is crop agnostic. If the crop is green and growing, and the firm can extract sap, it’s possible to do sap analysis, with over 200 crops covered.

“Most growers start with sap analysis because they want to know and manage their nutrient uptake from the soil to improve their fertiliser efficiency, and to avoid nutrient deficiencies or toxicities before they are visible in the plant,” he says. “Ultimately we want to save costs through optimum plant growth, health and quality.” Sap analysis tests for 16 different nutrients, including three ways of measuring of nitrogen, plus total sugars, the total dissolved salts (EC) and pH (see box).

Sampling is important – there are some basic rules to get it right to deliver the best results. These include sampling before 9am in the morning for full leaf tension and ensure consistency of results. The leaves must be dry – or dried with a tissue before sending – and free from dirt and disease, with the petiole or stalk that attaches the leaf to the stem removed. The analysis also compares young and old leaves, which must be sampled separately. If deficiency is showing sample these leaves separately from healthy ones. “That will give the best insight into what is the deficiency. “If you do a foliar spray then either sample before to help understand what correction to do or at least one week after, as there will always be residue on the leaves and this will influence the results,” adds Mr Hegger.

Samples should be sent in clean zip-lock bags, preferably using labels supplied by NovaCropControl. Around 85g is required for a wheat leaf sample. Delays in getting the samples to the Netherlands was an issue for some growers last season with changes in Customs rules following Brexit. Help and instructions for sending samples from outside of the European Union can be found on the NovaCropControl website.

“The main issue with delays of more than three to four days is with the quality of the leaves. As soon as the leaves are picked they start to decompose, and the longer they are in transport the more that occurs. It mainly increases ammonium levels and also the pH of the crop – the rest won’t really change.

“But the better the quality the leaves reach us, the better the results.”

• In part 2 next issue, we look at the science behind plant sap analysis to understand nutrient use in plants

-

My Nuffield Journey And Beyond

Nuffield Farming Scholar Andy Howard reflects on his Nuffield Scholarship and what it has enabled him to achieve since…

There were two key moments that got my Nuffield journey to the starting point. The first was sitting in a car with my friend and local farmer Tom Sewell, who was at that time in the midst of his Nuffield travels. Listening to him talk about his visits to foreign climes and inspirational farmers certainly got me interested in the idea of a Nuffield Scholarship. The second moment was going to a meeting and listening to this crazy French farmer, Frederic Thomas, talk about planting more than one crop species in a field at the same time, at that moment I knew I had a subject to study as well as the will.

The next stage was applying and going for my interview. I admit I have a supportive family at home and at work, which really helped, but many people say to me “I’d love to do a scholarship but just don’t have the time” or another excuse. My situation was that two days before my interview my second child was born and he ended up coming to the first Nuffield conference I went to at the age six weeks, so if I had enough time then most others will! The Nuffield staff are very helpful and flexible and will do their best to accommodate your situation. After the conference, the next stage was to plan and organise my twelve weeks of travel. That involved a lot of Googling, map staring and logistics. I ended up visiting 82 farmers and researchers in 10 different countries.

This involved a maximum of four weeks away at one time, which was difficult with a young family but there really is not anything better than getting away completely from the farm and immersing yourself in a study tour. It opens your mind to what could be possible to achieve at home on our farm but just as importantly, you realise that wherever you are farming in the world there is no-one who has perfected their system. This was a very important realisation for me and took pressure off me mentally, as you can convince yourself that the people who author books on your subject know it all and have immaculate farms. This I can tell you is not the case! Though the travelling and meeting of new farmers was an amazing experience, but it really is only the start. There are too many highlights to mention here, but you can visit my blog at the QR code below for more detail about my journey.

That section of my Nuffield Journey was only 18 months out of the total of a seven-year journey. More has changed in my life since I finished than did during my travels. You are told before you embark on a Nuffield Scholarship that it opens many doors, and this certainly has been true for me. One of the immediate changes was the amount of public speaking I have done since. Before my scholarship I would struggle to speak for more than 20 minutes at a farmers meeting, they now have to kick me off after 90 minutes. In the last 5-6 years I have spoken to over 100 different groups in different countries around Europe, something that would have been unimaginable before.

On the farm there too have been many changes. I realised from visiting many inspiring farmers that many of the artificial inputs we use are unnecessary. This led me to reduce our inputs by 10% every year for the last five years. This has not only made the farm more profitable recently but also made farming more exciting. We have changed from a boring, predictable synthetic input system to a knowledge intensive, flexible system that is constantly changing and evolving. The scholarship inspired me to change my drill so that it can cope with intercropping and plant different plant species at the same time. I have also built, with my father, a bespoke intercrop separator from many second-hand components (Image 3), so we can now separate the intercrops we grow on the farm.

Even before my scholarship, I had started to do on-farm trials by myself to investigate whether new ideas would work on our farm. This has accelerated exponentially since finishing my scholarship. People have wanted to collaborate with me on trials on farm and this has added some professionality and scientific rigour to the process. We have worked with PGRO, Innovative Farmers, Diversify Project and Southern Water, and the information coming from these trials has been invaluable to our business. In the last couple of years this too has led to me being involved with an Innovate UK funded project called “N2 Vision” ( N₂Vision – Automated Robotic Nitrogen Diagnosis of Arable Soil (wordpress. com) ) The project is investigating how AI, Deep Learning and Robotics can apply nitrogen fertilisers extremely precisely to arable crops.

There are hopefully more projects in the pipeline that we are going to be involved in which all stems from being a Nuffield Scholar. It is an exciting time to be involved in the cutting edge of agriculture. From becoming more well known since my scholarship and doing many public speaking events, my email inbox started to become regularly filled with requests for information and ideas. Firstly, this is very flattering that people think you are an “expert” in your field (most of the time I feel like a novice) but can also become time consuming. After a while I realised that this interest could be monetised and so I contacted a fellow Nuffield Scholar Stephen Briggs about joining Abacus Agriculture ( Abacus Agriculture Consultants – abacusagri.com ) and so started my career as a consultant, again something unimaginable before Nuffield.

The changes to the way we have farmed since 2015 have also changed the crops we grow and opened doors to different markets for what we grow on farm. We now grow crops for Hodmedods (Hodmedod’s British Pulses and Grains [hodmedods.co.uk]), who are an amazing company that promote and sell British grains and believe in a fair share of the benefits to the whole supply chain. They have been a breath of fresh air to work with as they are not trying to grind you down to the minimum price or try to put as many quality claims onto the farmer that they think they can get away with. A real vision of how the food system should work!!

The biggest benefit from my scholarship has been the network of friends I have made around the world. If I have any issues on the farm, I know someone will be able to help. Also, the numbers of visitors to the farm (pre-covid) meant we had regular visitors from around the globe that always kept life interesting and continued the learning experience. So, if the story above has not interested you in a Nuffield scholarship, then it may not for you. However, if your interest has been piqued, then go out and speak to scholars and just apply! What is the worst that could happen?

Applications for 2023 Nuffield Farming Scholarships are now open until 31 July 2022. To learn more and access the online application system, please visit www.nuffieldscholar.org.

-

In Search Of The Missing 30KG Of Nitrogen Per Hectare

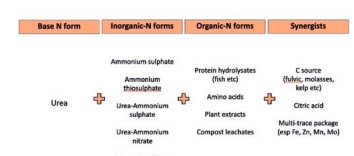

Written by Richard Rawlings, Agronomist, Zantra Ltd and Robert Patten, PlantWorks Ltd

The application of nitrogen on-farm will be under pressure in spring 2022, due both to its price, at the time of writing hovering at £650.00 /t and its availability, so far government intervention has done little to ease either price or supply.