If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

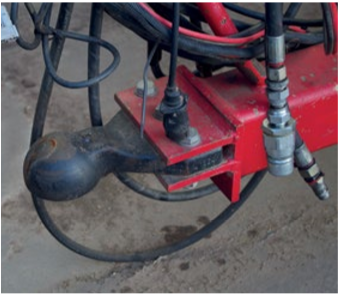

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Introduction – Issue 16

Farming is not the only industry to face tsunami-sized variations in product prices and input costs. Think airlines, oil, retail, manufacturing, restaurants, hair dressers, theatres… I recently had a very interesting conversation with a very senior oil man who explained the hugely difficult and expensive process of shutting down a refinery and the equal cost of starting it up again. He said that Shell, his company, were employing advisors far more than ever before, as the challenges, and costs of wrong decisions are so high.

“We’re excellent at operating plant, but find a second pair of eyes from outside the business is well worth while when looking at the direction the company needs to be moving.” I translated it to farming, and the move toward No-till, and wondered how many farmers turn to a second pair of experienced eyes. Like the oil-man, the good farmer can be excellent at squeezing profit from a relatively static situation, but may not have the eyes which see woods rather than trees when it comes to the long term.

Do you go green and go with the flow, or be controversial and opt to continue focussing on production? If it’s production, the perceptive long term advisor might well focus on climate change and the possible shortage of water, while the farmer may look at a new harvester or some extra land, issues which are shorter term. Farm planning needs a view over the horizon which might appear some way off at present, but will as sure as eggs is eggs come all too quickly.

Finding an advisor with vision who looks beyond the present is difficult. Years ago the avuncular bank manager performed as general consultant, advising on loans and farm development, and they have largely been taken over by consultants who want to do indepth surveys, before hopefully reaching a conclusion.

A Happy Christmas to all Direct Driller readers.

-

The Face of Farming Leadership

Some people are born to be leaders, most just learn on the way. The latter seems to be how it works in farming. Our leaders are bred. Groomed though various roles to be the right mix of farmer and business we need to represent us. I’ve had the pleasure in meeting some of the spokespeople of farming in the UK and very few strike me as born leaders. The born leaders are the one’s that inspire you being around them.

For instance, Minette is a brilliant public speaker, great on the TV and the perfect face of farming. Which is exactly what she needs to be as the public head of the NFU. Never has farming needed a presentable and eloquent public face as much. Minette deals with news presenters’ questions and vegan activists with exactly the articulacy we need. I doubt she inspires many farmers, but that’s not her job in my opinion. A job which I hope she keeps for a while longer and I’m sure she will just get better and better at. But she doesn’t lead the NFU. She represents it.

Who are our leaders then?

Jim Mosely CEO of Red Tractor, Nichols Saphir is Chairman of AHDB, Professor Caccamo is CEO of NIAB. It’s not them and we shouldn’t be looking to them. They organise and control, not lead. It’s certainly not the politicians or wannabe politicians. All of them are paid to do a job and after enough years of that, they seem to care more about the next role than the cause. The merry go-round of civil servants in our industry is blatantly wrong. Although it’s nice to see so much new blood coming in at AHDB from outside farming. Our leaders are the ones that make their voices heard and give their opinion.

Those that are both doing and talking, where farming is still more of their role (neatly ruled myself out there). There are so many examples, the farmer focus writers in this magazine, YouTubers, farmers doing their own farm tours, the speakers at Groundswell, the NFU county chairs. You have met so many of them and they have inspired you. They don’t claim to lead our industry, they just do. You have listened to them and acted on what they say. You have absorbed and learnt from them. That’s what leaders do.

Farming has plenty of leaders, they just aren’t who you think of when you say “leader” out loud.

-

The 8TH World Congress On Conservation Agriculture

The Future of Farming: Profitable and Sustainable Farming with Conservation Agriculture

Held virtually in June 2021 in Switzerland and attended by 783 participants from farmer associations, international organisations, scientific institutions, private sector, non-governmental and civil society organizations, from more than 108 countries, from the developed and developing world. The main objective of the 8WCCA was to celebrate the Conservation Agriculture Community’s success as the driver of the biggest farming revolution to have occurred in our lifetimes, and to build on this and boost the quality and speed of this transformation globally towards sustainable agriculture in support of the Sustainable Development and the international climate goals.

Naturally grown soil is a limited, scarce, non-renewable resource. It is the base for the production of healthy food and native wood, a buffer element for the global hydrological cycle, filter substrate for clean drinking water, global carbon store, habitat of a huge biodiversity and element of attractive landscapes. At the interface of atmosphere, hydrosphere and lithosphere, the soil fulfills indispensable ecological, economic and social functions. The future of the world’s food security requires soils which are unpolluted, of stable structure and productive, in short – a sustainable soil use. Conservation Agriculture (CA) and its many locally adapted variants offer the best means of using soils for productive farming while enhancing their ability to fulfil their vital societal and planetary functions.

Accumulated positive experiences and scientific knowledge about Conservation Agriculture (CA) are leading to its rapid adoption world-wide. Farmers now apply CA on over 200 million hectares (15% of the word’s annual cropland area) in over 100 countries across a diverse range of agro-ecological zones and farm sizes, in all continents but particularly in Africa, Asia and Europe. It has enhanced farm production and reduced costs while conserving and enhancing the natural resources of land, water, biodiversity and climate.

In contrast, conventional tillage practices are not ecologically sustainable since they degrade land by destroying soil structure and biodiversity, reduce soil organic matter content, cause soil compaction, increase run-off and erosion and contaminate water bodies with pollutants and sediments, threatening land productivity, environment and human health. In addition, they produce unacceptable levels of greenhouse gas emissions, speeding up climate change. World-wide, they have accelerated degradation of many natural ecosystems, decreased biodiversity and increased risks of desertification. CA avoids many of the negative consequences of conventional tillage agriculture by replicating natural processes through the continuous avoidance of soil tillage, permanent maintenance of a soil mulch cover through which diverse crops are directly seeded or planted and rainfall can enter the soil and be retained, cutting erosion.

CA enhances the crop root environment (soil structure, carbon, nutrients and moisture) and cuts the buildup of pests and diseases. 2 In these ways, CA results in a productive agriculture for food security and improved rural livelihoods, especially women’s welfare since they provide a high proportion of agricultural labour. Its many economic, social and environmental benefits justify a fundamental re-appraisal of common farming methods. This Congress has confirmed that CA is here to stay. It has shown that the CA Community is in very good health, full of energy and new ideas. It has confirmed the validity of the Community’s way of operating, with farmers in the driving seat, innovating, sharing experiences, spreading the word and creating demands for supportive services from the public and private sectors.

All of us who have participated feel proud of our Community’s achievements and are determined to do everything within our power – and working with others who share our determination – to contribute to the emergence of a truly sustainable future of farming worldwide. We are confident that the millions of CA farmers whom we have sought to represent here will echo our commitment. We call upon politicians, international institutions, environmentalists, farmers, private industry and society as a whole, to recognise that the conservation of natural resources is the co-responsibility, past, present and future, of all sectors of society in the proportion that they consume products resulting from the utilization of these resources, noting the increasing interest in plant-based diets to improve human and planetary health.

Further, it calls on society, through these stakeholders, to conceive and enact appropriate longterm strategies and to support, further develop and embrace the concepts of CA as a fundamental element in achieving agricultural-related Sustainable Development Goals including those with a social and economic perspective, and those of ensuring the continuity of the land’s ongoing capacities to yield food, other agricultural products, water and environmental services in perpetuity. It follows that the environmental services provided by farmers who nurture soil health should be recognised and recompensed by society.

Action plan

The Congress participants declare their commitment to engage the CA Community in achieving the following goal and to taking the actions needed for this.

Goal

Given the urgent need to accelerate the global move to sustainable food systems, and in particular to respond to the global challenge to mitigate the advancing climate change, the Congress agreed that the CA Community should aim at bringing at least 50% of the global cropland area or 700 million hectares under good quality CA systems by 2050. These holistic CA systems would involve CA farmers in engaging progressively in the full array of sustainable approaches to farming, adapted to their ecological and social conditions so as to maximise the sustainability benefits of growing crops without tillage.

Practical actions

To achieve the goal, a massive boost should be injected into the momentum of the CA Community’s activities with a concentration on the following six themes:

1. Catalysing the formation of additional farmer-run CA groups in countries and regions in which they do not yet exist and enabling all groups to accelerate CA adoption and enhancement, maintaining high quality standards. 3

2. Greatly speeding up the invention and mainstreaming of a growing array of truly sustainable CA-based technologies, including through engaging with other movements committed to sustainable farming.

3. Embedding the CA Community in the main global efforts to shift to sustainable food management and governance systems and replicating the arrangements at local levels.

4. Assuring that CA farmers are justly rewarded for their generation of public goods and environmental services.

5. Mobilizing recognition, institutional support and additional funding from governments and international development institutions to support good quality CA programme expansion.

6. Building global public awareness of the steps being taken by our CA Community to make food production and consumption sustainable.

In order to facilitate the implementation of above thematic activities, the Congress endorses the need to:

(a) operate the Global CA-CoP as an independent non-profit mechanism, with ongoing hosting support of ECAF and patronage by FAO, and with an advisory panel, and authorised to set up task forces and working groups to help implement the priority practical actions;

(b) strengthen the CA-CoP Moderator capacity within the CA Community;

and (c) create a CA Hall-of-Fame in time for the 9th Congress.

It would also oversee and support future processes for convening CA World Congresses. The Global CA-CoP would require a permanent IT systems development and operating capacity, with sound financial management, programme monitoring and reporting capacities.

The Congress participants feel confident that much of the extended moderation function can continue to be provided by CA Community participants who are willing to provide their time, knowledge, expertise and energy on a voluntary basis. This Congress has reinforced our conviction that it is entirely possible to meet the global goal of making our food systems sustainable in every sense of the word and that our Community has a vital role to play in this transformation. Our own experience shows that farming can quickly respond to new challenges when farmers see that these are in their own interests.

Our aim is to engage our whole Community as quickly as possible in creating and spreading optimal and profitable low-input, high-output CA-based farming systems that are dependent on biological forms of crop protection and plant nutrition management with maximum energy efficiency and minimal use of externally sourced inputs. This approach shows our commitment to making all we do together in future still better than what we now do! We pledge to work at all levels with all who share this vision of farming for the future, seeking their guidance and sharing what we learn with them. And we will also partner with those who champion complementary changes in downstream elements of the food chain to bring to healthy nutrition for all people and the elimination of food waste.

Healthy soils are the very heart of healthy lives and a healthy planet!

-

The Seed Microbiome

Written by Joel Williams

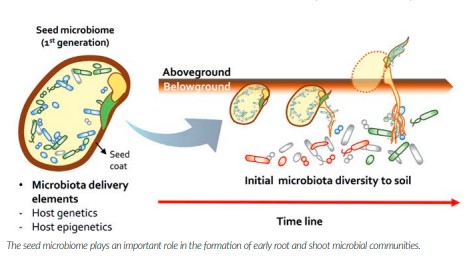

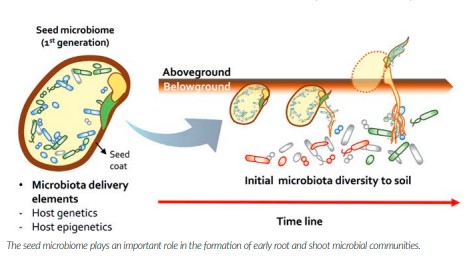

In the last article we introduced the various habitats that exist on and within plant tissues where a range of microbes coexist with plants and provide many benefits to growth and development. Despite the majority of microbiota living around plant root systems, there are also a range of microbes that also uniquely associate with plant shoots, leaves, flowers or seeds; and we are only just beginning to understand their importance. In this article we will take a closer look specifically at the seed microbiome and explore some of the factors that shape this biome and how this can be of benefit toward a more sustainable agriculture.

Like many other examples in agriculture where we have tended to focus on the negative, the prevalence of pathogens on seeds has been extensively studied and has dominated much of the thinking regarding seed microbiota. However, the occurrence and role of other beneficial microorganisms – which constitute a majority of the seed associated organisms – are relatively unknown. Seeds generally present similar proportions of bacterial and fungal diversity, which contrasts with other aboveground plant compartments that are for the most part, highly dominated by bacterial diversity. Microbial communities associated with the seed coat are usually more diverse than those associated within the seed – only a smaller number of specialist microbial species have the ability to pass through the external barriers of plant tissues and colonise tissues within; most others can only associate with the external surfaces.

In the same way that there are unique and distinct microbes that associate with different plant parts, there are also specific microbes that associate exclusively to distinct micro-habitats of the seed itself. There are three seed compartments where microbes associate – the embryo, the endosperm and the seed coat. Seed-associated microorganisms can be acquired either ‘horizontally’ from various and local environments (e.g. air, water, insects, seed processing) or ‘vertically’ passed down from the mother plant, and hence, transmitted across multiple generations. Overall, microbes associated with the embryo and endosperm (internally) are more likely to be transmitted vertically than those associated with the seed coat, these being mostly transmitted horizontally.

Three main transmission pathways have been documented:

1. The internal pathway – whereby microorganisms colonise developing seeds via the xylem or nonvascular tissue of the mother plant.

2. The floral pathway – whereby microorganisms colonise developing seeds via the xylem or nonvascular tissue of the mother plant.

3. The external pathway – that represents microbial colonisation of developing seeds through the stigma.

Of course, the development and application of the majority of seed treatment technologies have focussed primarily on the external pathway. Some of these inoculants are designed to remain on the outside and colonise the roots as they develop while some are destined to become endophytes and enter the plant tissues (such as rhizobia or some mycorrhiza for example). The exact mechanisms which determine the final structure and composition of the seed microbiome are still being elucidated but factors that influence this include a range of environmental conditions, soil type and perhaps most importantly, the host plant itself plays a major role in shaping its seed microbiome.

It is now understood that each and every plant species recruits and structures a microbiome unique to that species (referred to as its core microbiome), and even going beyond this, different varieties also shape their own ‘varietal specific’ microbiomes. These kinds of insights are opening some fascinating doors to understanding the species specific nature of plant-microbe interactions, which in the future will no doubt help design efficient production systems whereby plant varieties and microbial strains are highly aligned and optimised for various outcomes (plant health, pest resistance, nutrient use efficiencies etc). Although I fully support the use of highly diverse, broad spectrum and DIY inoculants like compost extracts, there are many examples whereby successful suppression of a pathogen (for example) is dependent on a specific antagonistic mechanism from one particular microbial species (or even strain); so illuminating some of these highly specific crop-microbe interactions at the molecular level will be a fruitful endeavour in years to come.

In the meantime, it is clear that the seed microbiome is of utmost importance to plant development – affecting growth, drought resistance, disease resistance and even flowering times. We know the seed microbiome becomes active immediately after sowing as the germination process begins. These microbes associated with the seed are the early risers so to speak and consequently play a key role – somewhat as gatekeepers – in safeguarding the seed and communicating to the rest of the soil biome and shaping which organisms from the soil can or can’t subsequently colonise the seed and the emerging roots and shoots.

This early structuring of the microbial community that subsequently colonises the plant can have major and long-lasting implications on how the root and shoot microbiome matures through the rest of the plant developmental stages. There are major knowledge gaps on the impact of fungicidal seed dressings on the nontarget organisms of the seed microbiome. We can safely assume that at least some beneficials will be compromised but whether the use of such inputs may be leading to negative consequences – such as greater disease susceptibility – in later crop stages remains to be studied. Even less understood is whether fungicidal dressings may be impacting the composition of the seed microbiome that is subsequently inherited from the mother plant to the next generation and hence inducing transgenerational changes in the seed microbiome over time.

Practically speaking, there are 3 take homes we can draw from these insights.

1. Eliminate the use of fungicidal seed dressings – if this idea is too daunting for you, start small. Choose half a field or a few tramlines and start the process on a small scale. Observe as you go and scale up in stages that are comfortable within your attitudes to risk.

2. Substitute dressings with bioinputs – rather than just cut out dressings, it really is preferrable to substitute the chemical with other biostimulants or bioinoculants. These could also be applied to the seed or injected into the furrow where possible. Input substitutions might include humic acid, fish hydrolysate or molasses along with some kind of microbial inoculant such as compost extracts or commercial products.

3. Save your own seed – considering that part of the seed microbiome is inherited from the local environment (mostly the soil), saving seed from plants that were grown in your soil is potentially optimising the microbiota that associate with your seeds to your specific soil type, growing conditions and management practices. There is still much to learn regarding these potential transgenerational effects but early indications suggest this is worth pursuing.

References

1. The variable influences of soil and seed-associated bacterial communities on the assembly of seedling microbiomes. (2021). doi:10.1038/s41396-021- 00967-1.

2. Seed microbiota revealed by a large-scale metaanalysis including 50 plant species. (2021). doi:10.1101/2021.06.08.447541.

3. Plant Communication With Associated Microbiota in the Spermosphere, Rhizosphere and Phyllosphere. (2017). doi: 10.1016/ bs.abr.2016.10.007

4. Inheritance of seed and rhizosphere microbial communities through plant–soil feedback and soil memory. (2019). doi: 10.1111/1758- 2229.12760

5. Revisiting Plant–Microbe Interactions and Microbial Consortia Application for Enhancing Sustainable Agriculture: A Review. (2020). doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.560406

-

History Of The GD

Written by Tony Gent

With over 60 years of farming, I have seen and been involved with so many changes, as a lad from working with horses and leaving school at 15 to working on my father’s smallholding with only 50 acres and a mix of cropping. The farm began to mechanise and expand, so did my interest in designing better tools, particularly to improve soil management. The need to produce crops in an economic and competitive way has always been my driving force, with the sustainability of the business as well as ecology and the environment.

We first started to notice the importance of soil condition in the 1960s, with taking on heavy distressed soil which was suffering from poor cultivation techniques, resulting in pans and compacted layers. Having mastered those problems it became obvious that moving soil around was not only complex and expensive, but the soil workability was deteriorating and more liable to slump, cap and puddle.

At that time larger more complex machinery was becoming available and seen as a major part of the solution. To take advantage of larger tractors, particularly tracklayers with threepoint linkage and larger 4-wheel drive in the 70s my first development was what became known as the “Wilder Pressure Harrow”, my own design of harrow which was manufactured and marketed by John Wilder Engineering. This consisted of ground following individual units mounted on a parallel linkage, pressurised by a floating hydraulic down force and tines that could be infinitely adjusted. This allowed the scrubbing frame to achieve a precise seed bed for both spring use, on overwintering ploughing and on heavy tined cultivation in the autumn. The Pressure Harrow was awarded a silver Medal at the Royal Agricultural show in 1977 for machinery innervation.

With much more emphasis on autumn crops, especially oilseed rape and September establishment of wheat, the Pressure Harrow became invaluable for scratch tillage that was widely adopted. However, to fight soils that were in a poor structural state causing rooting and drainage problems a means of lifting and shattering the soil with minimal surface disturbance was needed. Together with Ken Taylor a local agricultural engineer a low disturbance subsurface tine was developed. This featured a slender point and front shin together with large wings to shatter the soil with a wide lateral effect, allowing wide tine spacing. It achieved the effect of loosening all the soil with no layer mixing or bringing unwanted soil to the surface. It became known as the “Flat Lift”

Demand for this method of low disturbance soil loosening coincided with larger horsepower, mostly American, tractors becoming available and to meet the demand for the Flat Lift an engineering company was founded to manufacture and to market it, an agreement with Parker Farm equipment was put place with the product being known as “Parker Farm Flat lift” manufactured by Taylor-Gent Engineering. However, as others adopted this approach competition from more established companies became intense, and as a small specialist manufacturer it was not viable. The rights to the product were acquired by Spalding’s, who still market it as the original “Flat Lift”

There was no-doubt we were on the right lines with all this. However, the whole process had to change as attitudes to straw-burning changed in the early 90s. We had become experts at this, using combines fitted with spreaders to achieve a 100% burn, completely obliterating trash with no chemical help such as glyphosate. However, as autumn cropping became more common, the intensity of the burn inevitably led to straw-burning being banned, and it almost seems incredible now this practice lasted so long. Although we now realise what we thought was an idyllic situation, but with the first signs of chemical resistance creeping in especially with black grass and brooms we now realise this was an unsustainable situation.

The straw burning ban was a massive game changer, as we were growing lots of second and third wheats that were early drilled, producing high volumes of straw to deal with. We had to revert to moving soil around with some inversion or mixing to bury or at least incorporate the straw to some degree. This caused a massive reinvestment in machinery and power to rapidly recover aggressively moved soil into a suitable seedbed in a very short time.

During this period, we took advantage of land becoming available with rapid expansion in acreage. Much of this was again soil in a distressed state requiring lots of TLC. Also, with the new FBT and contract farming arrangements with strong competition the rents tendered subsequently proved to be far too high. We had no choice but to invest in lots of power and big soil moving and drilling kit. Due to our limited cash resources and our ability to mend and make, this was done with a focus on quantity rather than quality. At the end of this period, we owned 3 CAT Challengers and a full set of the kit to utilise them that was rapidly becoming very tired.

Into the 2000s now farming a large area, costs were rising, and we were in a period of low commodity prices with wheat as low £60 to £70 per ton and locked into historic rents that were proving unsustainably high. This all came to a head in the years 2004 to 2008 when we knew we would need to re-invest in newer machinery. Given the intense workload and poor margins, with no prospect of improvement this seemed a questionable investment and caused us to re-evaluate what we were doing.

It was at this time I had a chance coming together with the UK No-till pioneer Tony Reynolds. I was NFU County Chairman and he became my Vice Chair. Many of our NFU meetings would end in discussion around soils, much to the disquiet of some. This resulted in several visits to his farms to get an understanding of what he was doing and above all to tap into his knowledge and experience and gain confidence to try it for ourselves. Subsequently also becoming involved with experiences of the Europe wide ECAF (European Conservation Agriculture Federation) which he is part of.

We began to move towards a change in 2007 with the first wheat being established with the Vaderstad Rapid drill after a light scratch to allow the conventional light discs to penetrate undisturbed soil. This first year with wheat it was a success and very encouraging. We also attempted oilseed rape sowing with a hired Bertini drill into a heavy surface residue situation in wet conditions. This was a total failure due to slugs, hair pinning and toxin damage.

Drilling kit for No-till was somewhat limited at the time, and with our soil conditions resulting in producing large broken out clods with a solid tine and potentially high residue we felt we must stick to a rotating disc. The options were basically only Bertini or John Deere.

At that time, I was invited to Argentina to visit the Bertini factory in Rosario and attend the Expoagro Farm Show, where I found lots of Notill kit of various designs and creations, mostly very basic or locally specialist. It had the feel of being built in the farm workshop or by the local blacksmith, not at all to European standards except for a few more serious manufacturers like Bertini. Argentina was forced into No-till by economic pressures of direct commodity taxation forcing massive simplification with cultivations resulting in cost cutting. They had been advised that as result of this they would suffer approximately 20% yield loss, but the reality was after 5 years their yields were actually greater as a result of adopting Notill. Their perception, probably correct of Europe was that we were given so much financial support that we didn’t need to consider costs and we just wasted money on lots of complex kit with shiny new paint. I came home with what seemed to me a simple thought that if I pursued their logic of production methods, together with the benefit of the support it would be a win-win situation and basically that is what happened.

To make a solid start we needed to jump in, and the first necessity was a drill. Having seen both the Bertini and the John Deere in action, I liked the double disc system of the Bertini with its slender opening, low disturbance and so returning from Argentina I came close to placing an order for an 8 metre Bertini. However, considering that it was a box, end tow for transport drill and having experienced and seen its limitations in our wetter conditions thought better of it. So, to get us going a new John Deere 6 metre 750A was ordered for the 2008 autumn season to work alongside our team of Challengers and conventional 8 metre Vaderstad.

For this season all the rape was very successfully established, wheat direct drilled after Beans and some second wheat with the John Deere. With the second wheat we had an interesting and revealing comparison: our standard practice for a second wheat then was to plough followed by a press and then to aid weathering mostly the need for a second press with tines. At drilling three CAT challengers were in action with a primary seedbed cultivator, followed by a power harrow and then the 8 metre Vaderstad and then having to be rolled, 6 or 7 operations in total. I remember in one situation I was drilling a next field in the same rotational situation with one pass with a 150hp tractor and the new John Deere 750A. The No-till crop established well and became a robust crop and out yielded the conventionally established crop.

With this first year experience our direction became cast in stone from that point on and we began disposing of the now unwanted tractors and machinery, eventually resulting in the removal of a 1000hp from our system. By 2009 we were fully committed to No-till but in the subsequent years it was by no means plain sailing: and sometimes conditions weren’t exactly favourable, experiencing wet seasons and degraded soil that needed time to recover.

I felt that the compromise I had taken opting for a single disc drill was starting to show and began to reflect back to my observations with the Bertini double disc with much less disturbance of the opening and a kinder soil action. I became aware that Weaving Machinery were seeing opportunities in the No-till marketplace and revamping their Krause system into what became known as the Big Disc, of which we acquired an 8 metre version. It consisted of a double disc arrangement of a small disc running in the shadow of a larger disc thereby creating a very narrow opening, but the opening still had to be closed which was difficult in dry hard conditions and was only achieved by pressing and squashing in wet conditions. The problems were because of the unbalanced side pressures of large and smaller disc the rigidity of the linkage required the same robust construction that was needed with a single disc, and that was its failing which limited its effectiveness.

The breakthrough came with a passing comment from Tony Reynolds that if it was possible to cut into the soil at an angle to place the seed under a lip of soil it would be much easier to close the soil over the seed. The problem was how in practice to achieve this. My first indication of a possibility along these lines was becoming aware of the Canadian Saskatchewan “Barton Opener” which is a single angled undercut disc system. However, subsequent investigation found that it had limited minimal disturbance and seemed to have technical limitations with stability robustness.

I began to realise that to achieve stability with a disc system, the force of moving soil to create an opening needed to be countered by a stabilising force on the same bracket. I began by taking the standard Weaving Big Disc arrangement and hinging it on an angled pivot to create a neutral trailing action. I then gradually increased the angle from vertical to approximately 20° to 25°. This achieved the undercut angle I was looking for with the smaller disc on the upper side creating a wave of soil flowing over it with the rotation forming an opening with very little soil disturbance, damage, or side compression due to the soil being gently eased upwards. The larger disc formed the initial soil cut, helping with a precise and slender opening for the seed. The main benefits are that an opening is created to place the seed in the soil without having to move the soil sideways, so there is no requirement to return the soil back to cover the seed. It was often described as like lifting the edge of a carpet and placing seed under it and it then returning to position covering the seed (see attached photo of an early demonstration unit)

Weaving Machinery quickly saw the potential of the system and a manufacturing and marketing deal was agreed and production began in 2015. The GD (Gent Disc) drill quickly became extremely popular in the UK, many European countries and subsequently New Zealand.

Later that year I visited Australia and picked up a contact I had made with the famed Bill Crabtree “No-Till Bill” in Western Australia. He introduced me to Darryl Hine of Direct Seeding and Harvesting based in Albany WA. Darryl was one the leading exponents of introducing No-till machinery to Australia and was the importer and agent for the Canadian K-Hart range of disc drills.

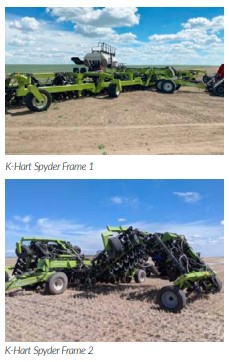

With introduction from Darryl, I then visited K-Hart at their premises in Saskatchewan, where I stayed for a few days with farmer and engineer Kim Hartman getting to know them and their product which was similar to Weaving’s and consisted of a conventional double disc system. We did some trials with some Weaving GD Units that had been sent to them, which they were impressed with and quickly saw the potential. Again, a deal for manufacture and marketing covering North America and Australia was put in place and with some redesign to adapt to their standard parts production began of the “K-Hart Gent Opener” in 2017, with modifications to the design to suit their conditions both in North America and Australia. I have subsequently visited both Canada and Australia to help with further design refinements and promotion of the opener where interest and sales are rapidly increasing. K-Hart has now evolved into an expanding company involving a new team to design and develop a specialist unique frame to suit the “Gent Opener” branded the “Spider” frame. These frames are up to (76ft) 24 metres wide which folds in 5 sections and have typically 100 to 130 openers.

Our farm has now been No-till for 12 to14 years and we have absolutely no regrets. As envisaged in the early stages, it has been a win-win situation of lower operating and input costs with sustained or improved yields. We now have a more sustainable rotation and massively improved soil with organic matter levels that started at near nil now close to double figures on many fields. The release of capital also allowed the business funds to invest in the massive expansion of a fledgling enterprise on the farm of Free-Range Egg production.

The transition from an intensive high input to a low input and much more rewarding and sustainable system has been a very interesting and a rewarding journey. New benefits are now emerging, with the demise of subsidy support on the horizon, addressing climate change and carbon sequestration. This latter opportunity has now been identified as an additional income stream that can help support and encourage more farmers in adopting No-till, so again we have a win-win situation.

-

Welcome To The 8TH World Congress On Conservation Agriculture

Speech given by Professor Amir Kassam

Friends, This is an historic day for the CA movement. It was twenty years ago that ECAF, the European Conservation Agriculture Federation, organized the First World Congress on Conservation Agriculture in partnership with FAO. Today, thanks to continued support from FAO and ECAF as well as other sponsors and especially SWISS NO-TILL, we are gathered together here in Bern and all around the world to celebrate our success as the drivers of the biggest farming revolution to have occurred in our lifetimes. Let us celebrate our joint engagement and contribution to transforming farming from being the main source of land degradation globally, to becoming a driving force for conserving and rebuilding healthy soils and agroecosystems so that they can sustainably meet the world’s future needs for food and other farm products while helping to slow the pace of climate change and ecological breakdown.

Let us celebrate our part in the 2 transformation of farming, from being a contributor to the many interconnected crises facing the world, to being a key part of the solution. It is no exaggeration to claim that our achievement in engaging millions of farmers across every continent in what has become known as Conservation Agriculture – or CA – has been a massive game-changer. We can and should take great pride in all we have done but we still face huge challenges to complete our revolution so that what we have pioneered is steadily improved and becomes the global norm in farming. Our task during these 3 days on-line, and in the field days, is to shape the future directions in which we need to move together to achieve this in the shortest possible time.

For this, we must apply lessons from our collective experience over the past 50 years or so. We have come this far because of the foresight and determination of some remarkable visionaries and pioneers – mostly farmers – in the USA, South America, Asia, Africa, Europe and Australia. These pioneers saw that conventional tillage, involving frequent inversion of the topsoil, was damaging the structure of soils, reducing their organic matter content, and making them susceptible to erosion by wind and water. They showed us that we could grow productive crops without digging or ploughing, and they devoted their lives to improving 3 CA technologies and sharing them with others in their own countries and beyond.

Rather than list these pioneers by name, I invite each of you to think back to the beginnings of CA in your own country and to reflect on the exceptional people who challenged conventional wisdom and put their ploughs aside. One of the most notable of the early CA pioneers in the Global South was Dr. Herbert Bartz who sadly died recently. In 1972, with encouragement from Rolf Derpsch from GTZ, he became the first Brazilian farmer to throw away his plough. From then on, he devoted his life to improving CA techniques and promoting CA in Brazil and globally. Now, Brazil has become a leading CA nation with 43 million ha – or nearly 80% of its annual cropland – under various forms of no-till agriculture. Herbert was hoping to be with us today and had prepared a brief video message to inspire us to follow in his footsteps.

I am delighted that his daughter, Marie, has joined us in this Congress, and she will have more to say about her father this evening at the Social event where she will be showing the video. I invite you to watch another video now which Herbert made not long ago for a CA Congress in Africa. Let me now briefly touch on our achievements When the pioneers of No-Till said that good crops could be grown without digging or ploughing, most farmers laughed in disbelief and dismissed them as dreamers. Now, just half a century later, millions of farmers all over the world have taken them seriously. They have embarked voluntarily on all kinds of CA systems, no longer carrying out any tillage on their farms. The global area farmed using CA systems has risen from less than 1 million ha in 8 countries in 1970 to 205 million ha in 102 countries in 2019.

This is 15% of the world’s cropland area. In Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Paraguay, South Africa, Uruguay and the USA, CA methods are applied on more than half their cropped area. From 1990 to 2009, the CA area globally increased at an average annual rate of 5.2 million ha, reaching about 100 million ha in 2008. From then on until now, the CA area expanded at double that rate, attaining an average of 10.5 million ha per year. This was largely because the global CA Community of Practice (CA-CoP) was established in 2008, with its own communication and 5 networking platform, and began to globalize CA through the farmer-led CA movement worldwide.

The CA-CoP, of which I am Moderator, is a fast-growing openended community in which any person or institution interested in CA is welcome. While its network and mailing lists extend its reach, it has no list of members, no membership fees, no hierarchical structure and no officers with executive powers. It is glued together by its adherents’ commitment to farming without soil tillage, their natural inclination to innovate and their enthusiasm to share their experiences. This has led to the formation of many local CA groups which, in turn, are linked to regional groups in regular contact with the Moderator.

With the valuable patronage of FAO and much goodwill and support from other international entities, the Global CA-CoP has come to play an important catalytic and facilitating role, including the promotion of regional programmes and national activities, sharing experiences, making information, especially on innovations, widely accessible, and engaging donors and financing agencies in funding local CA programmes. All of this has been done with the intent that farmers remain in the driving seat. The triennial Congresses provide the opportunity for all interested parties to take stock of progress, to share experiences and ideas, and 6 to chart the future directions in which the Community will seek to move.

This has clearly succeeded! CA is now practiced in all major climate zones in which there is farmed land – from the warm humid tropics to the cool temperate areas. And it is applied in all the world’s main farming systems. It has taken hold in rainfed and irrigated areas, short-term and perennial crops, mixed crop-animal farms and organic systems. It has been adopted by large-scale mechanised farms and by smaller farms where most of the work is manual. CA has also evolved into a wide range of complex farming systems which make the most of the improved soil conditions created by the absence of tillage. But in spite of all of this, our movement remains vulnerable to possible changes in the governance of our global food system.

A surprising threat could come from transnational corporations, convened by the World Economic Forum in Davos, which have declared a 4th industrial revolution. This would be based on harnessing ‘big data’ to tell every farmer what to grow and when to plant, and to manipulate consumers’ food choices. While they claim that this will cure the ills of the global food 7 governance system, I feel bound to ask: Will this address degradation of our common resources and the planet? Will this meet the needs of small-scale farmers and protect their seed, land and food sovereignty?

Will this change our food distribution system to a more equitable one that would eliminate hunger and lead us to healthier diets? In raising these questions, I am not denying that there are many valuable opportunities for widening the use of digital tools to empower farmers and consumers to make better choices – but without infringing on their rights to make their own decisions.

The reality is that we are the great farming revolutionaries of our time for large- and small-scale farmers. Together, by translating our knowledge and convictions into practical action on the ground, we are leading the most transformational revolution in how land is farmed since the inversion plough was invented in the mid-17th century.

We have successfully challenged the universally held assumption that most land has to be regularly and intensively tilled and chemicalized to be productive and profitable. We are also proving that the widely held view that smallholders have no future is nonsense. We do this because we believe in it, based on the evidence generated by the early no-till farmers. Nobody 8 has had to order us to stop ploughing and digging and nobody has had to pay us to change our ways! Farmers are the initiators and drivers of the CA movement, its main innovators, and its main promoters.

Their success, including spreading and adapting CA into new ecologies and farming systems, has led to the growing involvement of scientists and created a demand for specialised equipment and inputs that has expanded the participation of the private sector in our revolution. The main motivation for farmers’ engagement has been CA’s potential for net gains in productivity and incomes. By eliminating tillage, larger farmers have cut spending on farm machinery, inputs and fuel, while small-scale farmers have not only made big savings in time and human energy from excluding deep hand-digging, but they have also found that they can move into CA with few purchased inputs and rely on their own seeds.

Formal research systems have become increasingly engaged in comparing the impacts of different CA interventions especially on soil structure and biology, moisture retention, carbon sequestration and pesticidefree weed and pestmanagement. There is now a huge raft of easily accessible scientific studies on almost every dimension of CA applications. Thanks to the expanding databases of CA networks, FAO and Cornell 9 University, information is easily accessible on almost every dimension of CA in text-books, and in scientific and technical studies. In future, however, researchers and farmers must do much more to team up in generating new CA systems knowledge.

One feature of CA is that its adoption and spread does not follow traditional linear agricultural extension models that transfer the findings of researchers to farmers. Instead, farmers themselves play the major role in innovation through CA Farmer Associations, Farmer Field Schools, Clubs and Networks as well as through community engagement. These social institutions offer opportunities for sharing knowledge and for cultivating solidarity that stimulate change and self-empowerment. This works effectively for all farmers when their skills, and needs for seed, land and food sovereignty are respected and supported by governments and stakeholders in the public and private sectors.

True, the private sector has responded well to demand especially for machinery and inputs, but in many places, CA farmers call the shots and the private sector has to offer a mutually beneficial service support along the value chain. 10 We are pushing ahead with CA and improving it as we go, mainly because we have found our incomes rising and the quality of our farmland improving. CA differs from the dominant ‘industrial’ approaches to tillage farming that have been driven by the goal of ever greater intensification, aimed at maximising yields.

They use more and more inputs and need ever bigger investments. Over time, they all too often damage or destroy the soils and environment that provide the foundations for food production and environmental or ecosystem services, and also put human health at risk of nutritional disorders. In spite of CA’s rapid spread, tillage-based agricultural intensification continues to cause vast physical and biological soil degradation and erosion, forcing the abandonment of once productive agricultural lands, increasing the frequency of flood damage, polluting our environment with toxic chemicals, releasing high levels of greenhouse gases, wiping out biodiversity, and reducing adaptability and resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses as well as fostering resistance to antibiotics. It seems to come naturally nowadays for humans, at least in so-called ‘developed countries’, to think that more is better.

We now realise that satisfying the desire for more and more material things without considering their environmental impact is putting at risk the future 11 of our children and grandchildren, and of all those with whom we share the planet. CA’s success comes from deliberately moving in exactly the opposite direction. We are getting more from less and bequeathing a healthier planet to future generations. We have already shown the ability of CA’s core practices of no-till, soil mulching and crop diversification to provide an effective foundation for integrated biological pest management and for drastically reducing agrochemical use.

We have also shown in several environments with smallholders and large-scale farmers the avoidance of the use of pesticides for controlling weeds, insects and pathogens through for example Push-Pull strategies, techniques of planting green involving green manure cover crop mixtures, and manipulation of soil fungi-to-bacteria ratios. And many smallholder farmers are practicing CA without the use of any agrochemicals. This is why FAO placed CA at the core of their ‘Save and Grow’ global strategy for sustainable production intensification. CA is good for all farmers, good for the land, good for the planet and good for people.

Let us now look to the future of CA There is no doubt that CA is a success story that is here to stay and that it will continue to grow fast. But what 12 about our expectations for the outcomes of this Congress? The organizers of the Congress are convinced that CA must be the mainstay of the shift that the world has to make urgently towards sustainable farming and food systems. This is because we know that, for as long as most soils continue to be damaged by tillage, the world cannot reach the goal of making food systems sustainable. But we also recognise that some aspects of No-Till systems, as they are now generally practiced, are restricting sustainability.

Specifically, some No-Till systems with poor cropping diversity still remain too dependent on pesticides (especially herbicides), on mineral nitrogen fertilizers, and on unduly heavy farm machinery driven by fossil fuels. I am sure that you will all agree that this has to change. Within our global Community there are many precedents for moves in the right directions, but we need to throw our weight behind accelerating their enhancement and uptake, so that CA becomes synonymous with sustainable farming for the future. We also know that we cannot go it alone. We must engage globally and locally with the champions of other 13 essential elements of sustainable farming, especially those engaged in organic farming, integrated pest management, agroecology and regenerative farming systems in their various guises.

In return, all these farming systems can be helped to harness CA principles and practices. If we do not share our experiences, help each other and pull together, many of the international Sustainable Development Goals – the SDGs – relating to food, natural resources management and climate change will be unattainable. We also have an important role to play in the recently launched UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021-2030. I also suggest for your consideration that the time may have come for our Community to begin to help to shape food consumption patterns in ways that will relieve pressure on the world’s finite area of cultivable land rather than destroy forests and other vulnerable ecologies to expand farmed land, with doubly negative effects on the rate of climate change.

Fortunately, we are faced with a win-win-win opportunity, as the area under farming can be greatly reduced, environmental damage curbed and human health improved by inducing a shift towards predominantly plantbased diets: this, in turn, would cut demand for livestock feeds which has been a main driver of the recent damaging expansion in cropped areas especially in tropical regions. 14 It is against this background that I suggest that this Congress may wish to signal its support for a notional goal of having good quality CA-based systems fully applied on at least 50% of the world’s annual cropland area or 700 million ha by 2050.

I believe this is an attainable goal given that the global CA movement doubled the rate of uptake of CA during the last decade. The big challenge will be to graft the other essential elements of sustainable farming into all our programmes – including those in the existing 200 million ha already applying CA. Achieving this goal would require a massive boost to the momentum of our Community’s activities with a concentration on the stated six themes.

To move forward with this, strengthening of the Moderator capacity within the CA Community is now needed. Much thought must still to be given to this, but one thing is clear: we must retain the concept that, as now, our future actions must be guided mainly by a growing team of volunteers coming from within our midst who are committed to giving their expertise, time and energy to enhancing and spreading CA systems. Earlier, I paid tribute to our pioneers and champions. With millions of farmers now applying CA in its many variants across the world, I feel confident that plenty of 16 people will signal their willingness to dedicate themselves to moving our activities forward.

One of the few positive by-products of the COVID pandemic is that it has stimulated great advances in information and communications technology. We are applying some of these in this largely virtual Congress. Any new actions need to take the fullest possible advantage of these innovations. One important implication is that all those involved in any new programme moderation arrangements can make most of their inputs from where they live. Of equal significance is the huge opportunity that these technologies offer for accelerating the spread of advances in knowledge across our Community and beyond.

The Community’s strength has been built on farmer-to-farmer sharing of experience, usually within their own localities and sometimes through country exchange visits. Now these farmer-to-farmer exchanges can instantaneously become global. And so, we shall nurture the emergence of a stronger moderating mechanism that will function almost entirely virtually. It would enjoy the guidance of an advisory panel, representing regional and national interests and those of cooperating institutions. It would have the capacity and power to set up task forces to 17 push forwards on each of the 6 main themes – and any more that might be added.

And it would need to have a permanent IT systems development and operating capacity. It would also oversee and support future processes for convening CA World Congresses. Finally, it would have to be set up as an entity – perhaps as a nonprofit organisation — with sound financial management, programme monitoring and reporting capacities. Finally, though this may seem a minor issue, I also propose that we convene a small working group to set up arrangements for honouring our pioneers through creating a CA Hallof-Fame in time for the 9th Congress. To get started immediately on this expanded agenda, ECAF has generously agreed that elements of the Congress Secretariat can continue to assist the Moderator in moving ahead with these new arrangements.

I hope that we can also continue to benefit from the patronage offered by FAO since our work began. I am confident that this Congress will, like earlier ones, give a great boost to our efforts and set the stage for a very bright future – a future in which our Community will play a hugely important part in the race to make the world’s food systems properly sustainable. 18 Thank you all for joining us at this challenging moment in our history. My very best wishes to you all for a truly inspiring congress.

-

Farmer Focus – Andrew Jackson

Harvest has come and gone. Yields were good but could have been better had the growing season not been so variable. We had trimmed our Nitrogen rates to 160 Kg/N/Ha for wheat and OSR, but huge swings of yields within the fields told me that the yield had not been altogether determined by the fertiliser rate but more by the soil type.

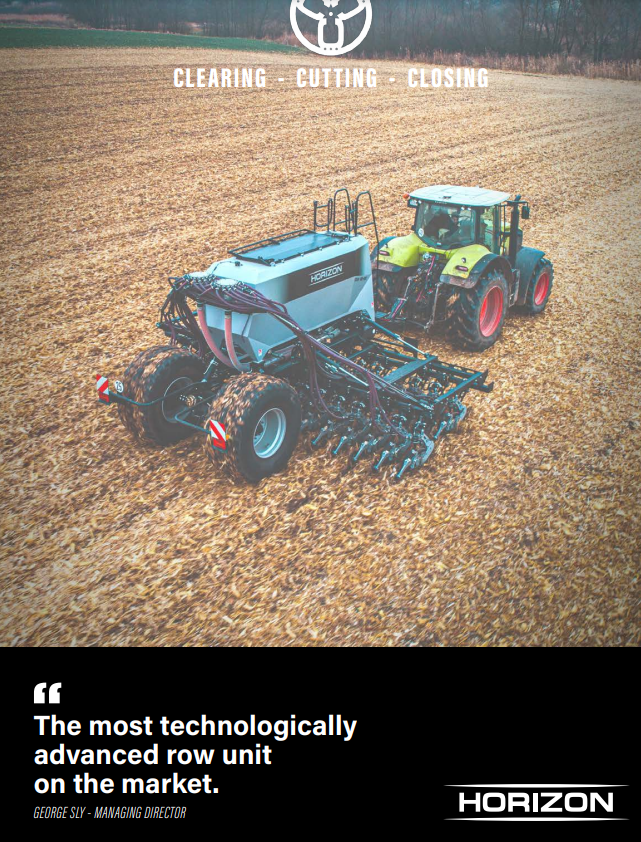

Harvest has come and gone. Yields were good but could have been better had the growing season not been so variable. We had trimmed our Nitrogen rates to 160 Kg/N/ Ha for wheat and OSR, but huge swings of yields within the fields told me that the yield had not been altogether determined by the fertiliser rate but more by the soil type. This autumn our OSR has been drilled mostly with the Horizon drill, which means no leading leg to loosen the soil, most farmers place the seed behind a subsoiler leg, because OSR can be a lazy rooter, so I am a little out of my comfort zone and we will have to wait and see. The rate of DAP has also been dropped to reflect a nitrogen application of 15Kg/N/Ha.

The results from the Horizon drill have been pleasing. We have succeeded in uniformly sowing, four millimetres deep for quinoa and grass seed and twenty to thirty millimetres deep for wheat and meadowfoam. Although a small company, I feel that if you are looking for a no-till disc drill, I would recommend the Horizon along with demonstrations of the more established drill manufacturers. As we look to the future and the threat of losing glyphosate, my thoughts are that maybe the drill manufacturer should sell inter-row guided weeders which are compatible with the drill sizes and coulter widths. This may be blue sky thinking but the Chameleon drill has already gone through this thought process.

After exploring the options of mixing a Johnson Su compost extract with “out of the grain store “wheat seed, I stumbled across an Agritrend concrete mixer bucket. I mentioned in my previous article about the Haggerty’s in Australia were using a grain auger to blend the liquid extract with the seed, however for some reason or other I thought that I would go with the concrete mixer bucket and if all else failed at least I would be able to mix reasonable volume of concrete. The cost of the bucket was more than most would want to pay, but I am pleased to report that Anna and I successfully mixed or blended ten litres of liquid with half a tonne of seed, we then opened the chute at the bottom of the bucket and let the bucket sweep the seed into the drill. This was a batch operation, and four batches filled the drill. The seed flowed well through the metering devices and has emerged evenly, will it make a yield difference? Watch this space.

David White kindly alerted me to Michael Horsch’s Christmas Fireside chat on YouTube. It was an enjoyable video and at one point Michael discussed making compost in Bavaria using a blend of green chopped cover crop together with chopped straw, the idea being that the straw might turn to some sort of biochar within the compost. The compost would be anaerobic and therefore did not require turning, this appealed to the lazy part of my nature. My brain engaged gear, I did not have access to chopped cover crop, but I did have an aftermath of grass after the grass seed had been harvested (with a stripper header), as well as access to straw. The other benefit would be keeping the straw and grass in the loop of the farm, also avoiding buying in any contaminated compost.

I eventually contacted Michael Horsch to learn a little more about the process, to my astonishment, I got an email from the man himself. I was almost as exciting as receiving an email from the Queen. Michael explained that the constituents were roughly 50:50 and pointed me towards work that had been carried out by Walter Witte from East Germany.

Much of the Walter Witte work was in German but I gleaned that volcanic rock dust was also added, the sides Mixing Johnson Su of the clamp should be consolidated, and the height of the clamp should be around 2.5 metres high. After Christmas I watched more YouTube, this time on Bokashi which is an additive to assist anaerobic composting, Bokashi can be mixed by yourself, but I decided to buy some from Agriton. This wacky plan was coming together. The Michael Horsch YouTube showed the forage being chopped and collected with a Pottinger forage wagon. I was reluctant to go down that route and eventually found a contractor who used a whole crop forage harvester to collect the compost constituents and apply the Bokashi liquid. Andrew Sincock from Agriton suggested adding seashells and I also purchased some rock dust from Remin.

On the day of the compost making, there was much more grass than I had estimated, so the quantites of straw, rock dust, seashell and Bokashi mix could have been increased. The product was placed on a concrete pad and Carl mixed the whole lot with our loading shovel. We are now the proud owners of about 700 tonnes of compost which may or may not be of any benefit, again watch this space.

My daughter Anna who changed her career at the beginning of lockdown to become a farmer, has gone through a huge learning curve. A lot of what I learnt at Agricultural college is not particularly relevant to this new system of Regenerative farming, so Anna is learning everything alongside me. Anna has a new border collie pup dog called Luna who has got through the biting stage and may be introduced to sheep training soon. One hurdle might be that neither Anna or myself can whistle and Anna has tried the half moon whistles that go inside your mouth but that too, is not going well. Luckily Anna has found a group of ladies on Facebook called “Ladies who lamb”. She has so far quizzed them on various aspects of husbandry as well as what is the best footwear, I suggested that she quizzes them about whistles. She mentions that the ladies’ group of sheep farmers is incredibly positive and encouraging, whilst the men’s group needs to work on the supportive element.

Anna has been a photographer and is familiar with social media. This got us into another scrape after I responded to a Base UK committee request from Satchel Classes. They wanted someone to promote Agriculture as a career opportunity, I volunteered Anna and myself and last week we jointly made a YouTube video to promote the cause. There were a lot of mistakes, but the Satchel people liked it, I hope that our mistakes might bring in a comedy element to hold the children’s attention.

Anna has also been approached by a film crew wanting to make a UK equivalent of “Kiss the Ground”, their version will be called “Six inches of Soil”, I will probably be asked to consult on the movie.

“There’s really only one place where we can put all the carbon dioxide and that’s in the land” quote from US farmer Ray Mc Cormick, Indiana. This sentence resonated with me and echoed what many books have been trying to put over. It’s just a great shame that people in government don’t read the same books as me. BASE UK exists to share and transfer knowledge relating to conservation agriculture and the modern name of regenerative agriculture and it is these agricultural practices that could as Ray states above, help save the planet.

Throughout the summer Base UK members are encouraged to host farm walks and invite other Base members. Probably nationally there are hundreds if not thousands of farmers who look over hedges at no-till practices and half hope that the no-till farmers with their much reduced workloads, might go bankrupt in five years, thus, proving their conventional system to be right and regen farmers to be wrong. It occurred to me that I should also invite non-Base members to my farm walks, to explain what I am trying to achieve. Hopefully other Base members in my region could also host farm walks where we could all invite a non regen farmer, thus creating some debate over a beer and a bar snack in the pub afterwards.

Within the last year and a half, the Base UK membership has grown from around 200 to 483, this is a good news story, and I would strongly recommend that you sign up for the Base UK Conference in February 2022. The capacity of the Crowne Plaza Hotel in Nottingham will be 300 and bearing in mind the size of the membership, to benefit from the great line up of speakers and the social networking with like-minded people, it would be wise to secure a place in good time.

For recent regen updates follow Anna’s Tik Tok

account. @farmerAnnaJackson. -

Are You Happy With The Quality Of The Lime You Purchase?

Written by James Warne from Soil First Farming

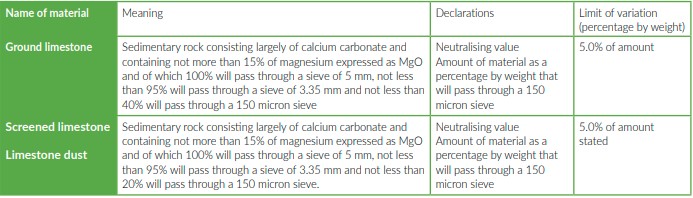

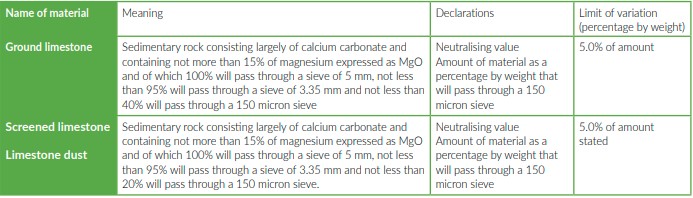

A word of warning to all of you who buy bulk lime products. There appears to be nobody in the supply chain fighting your corner to ensure the quality of the lime you buy meets the legal requirements as laid down in the Fertiliser Regulations 1991. 100% of the bulk lime products we see tipped on farm does not meet these specifications in terms of particle size. Even if it’s being sold as screened lime it fails to make the specification. This low quality lime will not be able to neutralise soil acidity as quickly, or for as long, resulting in declining crop performance. I encourage everyone buying bulk lime products to take a sample from the delivered pile before spreading and get it tested for Neutralising Value (NV) and particle size distribution to make sure it meets to specifications of the product. The correct specification is given in the table below. If the analysis results show substandard product, talk to your supplier and send the results to the Aglime Association. It’s only by collective effort that we can encourage change. Always request ground agricultural lime from your supplier and put it in writing.

The Aglime Association, which represents lime producers, has launched its own assurance standard to ensure product consistency from the quarries. But why do we need another assurance standard when the supply requirements are laid down in law? I mention this topic regularly for good reason. Farmers are paying for sub-standard inputs which can be very costly, not only in the purchase and spreading price, but also the knockon effects of reduced output. Low soil pH can negatively affect nitrogen use efficiency. With urea trading at ~£700/per tonne you need to ensure that you are maximizing its efficiency.

All ag-lime sold in the UK must meet the requirements of the Fertiliser Regulations 1991 to be sold as lime, for the purposes of this article I will look at limestone only, but these regulations also apply to dolomitic limestone, chalk and many other types of lime. The table below is taken from the Fertiliser Regulations.

Grind size

Don’t just buy on neutralising value, the particle size distribution is critical, almost more so. To put it in context, Lincoln Cathedral has a neutralising value, it’s built of limestone after all, but it won’t neutralise very mush due to the low surface area to volume ratio. Grind the stone to 150 micron and it will neutralise acid, provide plant available calcium and react well. Once the levels start to decline the effectiveness of inputs also starts to decline and the return on investment declines alongside. The health of the crop suffers which results in an increase in inputs which are already under pressure. You can see this becomes an ever-decreasing circle of increased cost and decreasing output.

As mentioned above we now know that grind size is as important as neutralising value in determining whether the lime will actually do as intended. This is where the fertiliser Regulations 1991 become relevant because they set out the standards for lime quality as a fertiliser. If we consider these regulations for a moment it is clear that both the neutralising value and the specific material name must be given, in addition the percentage by weight passing through a 150 micron sieve must also be declared (the grind size). A limit of variation (tolerence) of 5% is allowed.

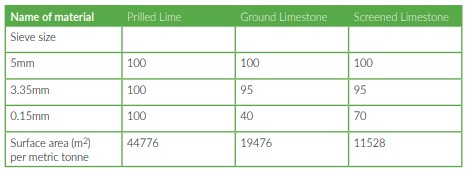

By grinding the rock finer we are increasing the surface area of the product. It is this increase in surface area which allows the lime to react faster and bring about quick reductions in soil acidity. If we calculate the degree of grinding and surface area we can see from the table above that ground limestone has a surface area nearly twice that of screened limestone, while prilled lime products can be four times the surface area of screened limstone. This increase will give greater reaction and therefore faster pH reduction.

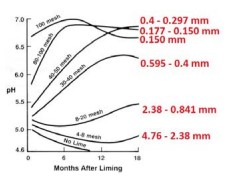

So how fine does the rock need to be ground to be effective? The aglime website states that “coarser material requires a heavier application” and “There is a considerable reduction in the effectiveness of liming materials containing particles above 600 microns (0.60mm, 60 mesh) unless the material is easily broken down”. The finer the lime is ground, the more effective it becomes. This is supported by work taken from North Carolina University in the US shown to the right;

This graph clearly demonstrates that lime in the range of 0.177 – 0.150mm (177-150 micron or 80-100 mesh) gave the quickest pH rise and most sustained pH rise. The larger particle size 0.841mm and above gave a very limited pH increase and took 18 months to achieve it. Focus on the detail of the basics and the output and profitability will follow. My advice to you is avoid buying bulk lime altogether because you cannot guarantee what you are going to receive and instead buy a guaranteed quality product such as a prilled lime which will work for you every time.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

With an increasing number of growers now reaping the benefits of lower disturbance drilling such as the Mzuri

system, we take a closer look at other implements which can prove invaluable to those on the direct drilling journey.Stubble Rake

As we say on our own farm, ‘It starts with the combine’. The first step in direct drilling a typical field is combining the previous crop, so it is only right that this step sets up the field for effective drilling and makes best use of any remaining crop residue. That’s why we like to use the Rezult stubble rake to even out any combine mishaps and ensure an even coverage of straw across the field. Fitted with leading discs, these make an invaluable addition to any rake for chopping surface straw and mixing it with surface tilth to accelerate decomposition. This tilth also makes it easy to create stale seedbeds and encourages a flush of weeds and volunteers ahead of drilling.

A couple of passes of the Rezult, a few weeks apart can make best use of chemistry for an effective weed kill. By opting for a stubble rake with leading discs, it also gives operators the added flexibility to use as a means of establishing low-cost cover crops when fitted with a seeder box.

The Rezult rake is also an ideal tool for cutting slug activity, particularly in OSR stubbles, where disrupting slug habitats and exposing eggs to the midday heat has huge advantages for reducing slug populations in the following crop. For Rezult’s fitted with a seeder box, slug bait can be applied at the same time to pack an even bigger punch.

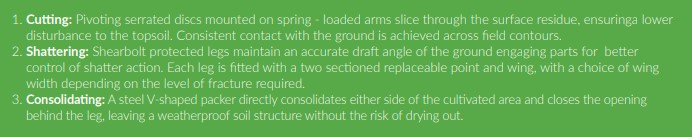

Low Disturbance Subsoiler

Whether it forms part of the transition to direct drilling, or used periodically for fields requiring remedial care, a low disturbance subsoiler is a great addition to the direct driller’s arsenal. Our Rehab low disturbance subsoiler has been redesigned for 2021 featuring leading discs, shearbolt protected legs and heavy-duty V-shaped roller packer. As direct drillers turn to less disturbance, some growers report experiencing compaction issues at depths of 6”-8” as a result of machinery passes or long periods of heavy rainfall. The Rehab has been designed to alleviate this type of compaction whilst staying true to growers’ requirements for low disturbance.

The Rehab features spring loaded pivoting discs which act to slice through topsoil and crop residue, allowing the following leg to lift and aerate the soil profile whilst minimising disturbance to the field surface. A generous leg spacing of 500mm and a stagger of 750mm promotes an excellent flow of crop residue through the implement to reduce the risk of blocking up in high-residue environments – something which is important to maintain for many direct drillers. Operators can determine the level of fracture through the soil profile by choosing from three wing widths including 55mm, 115mm and 135mm. The legs are protected by ‘hammer-thru’ shearbolts rather than hydraulically pressurised to maintain maximum draft control and the correct draft angle of the wing for more efficient use and lower disturbance.

When designing the Rehab, it was important to create an implement that would leave the field with a weatherproof finish, perfect for direct drilling. The Rehab achieves this by incorporating a V-shaped packer roller which is designed to consolidate either side of the leg and leave an even finish. By minimising surface disturbance and working with previous crop residue, the Rehab achieves better moisture retention whilst ensuring sufficient lifting of the soil profile, complimenting direct crop establishment.

-

Farmer Focus – Tom Sewell

The good the bad and the ugly!