If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Agricology What Is Healthy Soil Video

A healthy soil is vital to ensure both high yields and future high yields, as well as environmental protection – there are no negative consequences on the ecosystem from having a healthy soil! But what is a healthy soil?

Soil health can be defined as a soil’s ability to function and sustain plants, animals and humans as part of the ecosystem.

However, due to the opacity of the soil and the fact that (most of the time) plants grow, the health of the soil is often over-looked. There are five main factors that impact the health of the soil and can have a large influence over its capability and resilience to function, they are:

1. Soil structure

2. Soil chemistry

3. Organic matter content

4. Soil biology

5. Water infiltration, retention and movement through the profile

A healthy soil will have a good combination of all these factors, whilst an unhealthy soil will have a problem with at least one of these. Whether there are structural problems – compaction, plough pans; or waterlogging; these issues will have a cascade effect until all the other factors are impacted. A healthy soil will provide a buffer to extremes in temperature and rainfall – reducing the impact of extreme weather events; it will also be able to maintain productivity and function within an agricultural system. A healthy soil has plenty of air spaces within it, maintaining aerobic conditions.

When a soil has limited air spaces, anaerobic conditions dominate, leading to waterlogging and stagnation of roots and the proliferation of anaerobic microbes and denitrification (the loss of nitrogen from the system). A healthy soil will filter water slowly, retaining the nutrients and plant protection products (PPP) applied to the crop. If rainfall moves through the soil profile too quickly or if it is prevented from entering the soil through compaction or soil sealing, surface runoff increases, taking soil, nutrients and PPP with it, increasing the risk of flooding.

The potential of cover crops and no-till

At the Allerton Project we have been involved in investigating the sustainable intensification of agriculture through different experiments. Some researchers have investigated cover crops – which have been suggested to be the answer to everything; reducing soil erosion and leaching, whilst increasing water retention, soil organic matter and improving soil structure, as well as potentially suppressing weeds – although our results at this time do not confirm all of this. Other research has focused on moving away from conventional agricultural practice, with greater emphasis on no-till.

One of the fields at the Allerton Project has not been ploughed for the last 14 years and the soil structure is visibly different compared to other soils on the farm. No-till systems can help improve soil fertility, create changes to the structure and properties of the soil due to the stability of the environment, and enhance soil biology. Over time the no-till field has had the highest yields compared to the conventional field equivalent on the farm. Soil compaction is easily created – one pass of farm machinery at the wrong time (when the soil is waterlogged) can create a compacted layer, which can take many years to remediate. Understanding the mechanisms of compaction and how to alleviate it is another experiment occurring at the Allerton Project this year.

Overall, crop choice, rotation, and management, as well as establishment practice and maintenance can all greatly affect the “health” of the soil.

Dr Felicity Crotty is the Game and Wildlife Trust Allerton Project’s resident soil scientist. She writes:

“I have been researching soil biology and soil health for the last ten years. Firstly, I studied the soil food web during my PhD at Rothamsted Research (North Wyke) and subsequently as a post-doc at Aberystwyth University working on the PROSOIL project, which investigated maintaining healthy soil on livestock farms in Wales; and the SUREROOT project, that studied the effects of festuloliums as a forage crop. I joined the Allerton Project in 2015. My research covers all aspects of soil science – biology, physics and chemistry; although my main areas of expertise are soil biology, earthworm, mesofauna and nematode identification. Understanding how different management strategies and cropping systems effects the environment is key to sustainable farming and through my work I investigate these changes over time. The main projects I have been working on have been the Sustainable Intensification Research Platform and the EU Horizon 2020 project SOILCARE.

-

What Do You Read?

If you are like us, then you don’t know where to start when it comes to other reading apart from farming magazines.

However, there is so much information out there that can help us understand our businesses, farm better and

understand the position of non-farmers.We have listed a few more books you might find interesting, challenge the way you currently think and help you farm better.

The Carbon Farming Solution

Agriculture is currently a major net producer of greenhouse gases, with little prospect of improvement unless things change markedly. In The Carbon Farming Solution, Eric Toensmeier puts carbon sequestration at the forefront and shows how agriculture can be a net absorber of carbon. Improved forms of annual-based agriculture can help to a degree; however to maximize carbon sequestration, it is perennial crops we must look at, whether it be perennial grains, other perennial staples, or agroforestry systems incorporating trees and other crops. In this impressive book, backed up with numerous tables and references, the author has assembled a toolkit that will be of great use to anybody involved in agriculture whether in the tropics or colder northern regions.

For me the highlights are the chapters covering perennial crop species organized by use staple crops, protein crops, oil crops, industrial crops, etc. with some seven hundred species described. There are crops here for all climate types, with good information on cultivation and yields, so that wherever you are, you will be able to find suitable recommended perennial crops. This is an excellent book that gives great hope without being naïve and makes a clear reasoned argument for a more perennial-based agriculture to both feed people and take carbon out of the air. Martin Crawford, director, The Agroforestry Research Trust; author of Creating a Forest Garden and Trees for Gardens, Orchards, and Permaculture

Mycorrhizal Planet: How S y m b i o t i c Fungi Work with Roots to Support Plant Health and Build Soil

An Mycorrhizal fungi have been waiting a long time for people to recognize just how important they are to the making of dynamic soils. These microscopic organisms partner with the root systems of approximately 95 percent of the plants on Earth, and they sequester carbon in much more meaningful ways than human “carbon offsets” will ever achieve. Pick up a handful of old-growth forest soil and you are holding 26 miles of threadlike fungal mycelia, if it could be stretched it out in a straight line. Most of these soil fungi are mycorrhizal, supporting plant health in elegant and sophisticated ways. The boost to green immune function in plants and communitywide networking turns out to be the true basis of ecosystem resiliency. A profound intelligence exists in the underground nutrient exchange between fungi and plant roots, which in turn determines the nutrient density of the foods we grow and eat.

Exploring the science of symbiotic fungi in layman’s terms, holistic farmer Michael Phillips (author of The Holistic Orchard and The Apple Grower) sets the stage for practical applications across the landscape. The real impetus behind no-till farming, gardening with mulches, cover cropping, digging with broadforks, shallow cultivation, forestedge orcharding, and everything related to permaculture is to help the plants and fungi to prosper . . . which means we prosper as well.

Building soil structure and fertility that lasts for ages results only once we comprehend the nondisturbance principle. As the author says, “What a grower understands, a grower will do.” Mycorrhizal Planet abounds with insights into “fungal consciousness” and offers practical, regenerative techniques that are pertinent to gardeners, landscapers, orchardists, foresters, and farmers. Michael’s fungal acumen will resonate with everyone who is fascinated with the unseen workings of nature and concerned about maintaining and restoring the health of our soils, our climate, and the quality of life on Earth for generations to come.

A Soil Owner’s Manual: How to Restore and Maintain Soil Health

A Soil Owner’s M a n u a l : Restoring and Maintaining Soil Health, is about restoring the capacity of your soil to perform all the functions it was intended to perform. This book is not another fanciful guide on how to continuously manipulate and amend your soil to try and keep it productive. This book will change the way you think about and manage your soil. It may even change your life. If you are interested in solving the problem of dysfunctional soil and successfully addressing the symptoms of soil erosion, water runoff, nutrient deficiencies, compaction, soil crusting, weeds, insect pests, plant diseases, and water pollution, or simply wish to grow healthy vegetables in your family garden, then this book is for you. Soil health pioneer Jon Stika, describes in simple terms how you can bring your soil back to its full productive potential by understanding and applying the principles that built your soil in the first place. Understanding how the soil functions is critical to reducing the reliance on expensive inputs to maintain yields.

Working with, instead of against, the processes that naturally govern the soil can increase profitability and restore the soil to health. Restoring soil health can proactively solve natural resource issues before regulations are imposed that will merely address the symptoms. This book will lead you through the basic biology and guiding principles that will allow you to assess and restore your soil. It is part of a movement currently underway in agriculture that is working to restore what has been lost. A Soil Owner’s Manual: Restoring and Maintaining Soil Health will give you the opportunity to be part of this movement. Restoring soil health is restoring hope in the future of agriculture, from large farm fields and pastures, down to your own vegetable or flower garden.

For the Love of Soil: Strategies to Regenerate Our Food Production Systems

Learn a roadmap to healthy soil and revitalised food systems for powerfully address these times of challenge. This book equips producers with knowledge, skills and insights to regenerate ecosystem health and grow farm/ranch profits. Learn how to:- Triage soil health and act to fast-track soil and plant h e a l t h – B u i l d healthy resilient soil systemsDevelop a deeper understanding of microbial and mineral synergies-Read what weeds and diseases are communicating about soil and plant health-Create healthy, productive and profitable landscapes.

Globally recognised soil advocate and agroecologist Nicole Masters delivers the solution to rewind the clock on this increasingly critical soil crisis in her first book, For the Love of Soil. She argues we can no longer treat soil like dirt. Instead, we must take a soil-first approach to regenerate landscapes, restore natural cycles, and bring vitality back to ecosystems. This book translates the often complex and technical know-how of soil into more digestible terms through case studies from regenerative farmers, growers, and ranchers in Australasia and North America. Along with sharing key soil health principles and restoration tools, For the Love of Soil provides land managers with an action plan to kickstart their soil resource’s wellbeing, no matter the scale.“For years many of us involved in regenerative agriculture have been touting the soil health – plant health – animal health – human health connection but no one has tied them all together like Nicole does in “For the love of Soil”! ” Gabe Brown, Browns Ranch, Nourished by Nature.

“William Gibson once said that “the future is here – it is just not evenly distributed.” “Nicole modestly claims that the information in the book is not new thinking, but her resynthesis of the lessons she has learned and refined in collaboration with regenerative land-managers is new, and it is powerful.” Says Abe Collins, cofounder of LandStream and founder of Collins Grazing. “She lucidly shares lessons learned from the deep-topsoil futures she and her farming and ranching partners manage for and achieve.”The case studies, science and examples presented a compelling testament to the global, rapidly growing soil health movement.

“These food producers are taking actions to imitate natural systems more closely,” says Masters. “… they are rewarded with more efficient nutrient, carbon, and water cycles; improved plant and animal health, nutrient density, reduced stress, and ultimately, profitability.”In spite of the challenges food producers face, Masters’ book shows even incredibly degraded landscapes can be regenerated through mimicking natural systems and focusing on the soil first. “Our global agricultural production systems are frequently at war with ecosystem health and Mother Nature,” notes Terry McCosker of Resource Consulting Services in Australia. “In this book, Nicole is declaring peace with nature and provides us with the science and guidelines to join the regenerative agriculture movement while increasing profits.”Buy this book today to take your farm or ranch to the next level!

Teaming with M i c r o b e s : The Organic G a r d e n e r ‘s Guide to the Soil Food Web

-

Introduction – Issue 10

We, the readers of Direct Driller, need to give a huge round of applause to Clive and Chris, the energy behind this magazine, together with all the contributors to this issue. The contents is truly awe-inspiring, and the knowledge it contains colossal. It’s impossible to pick individual articles because that relegates the others, and it is all Premier League stuff. It may be pie in the sky, but I continue to envisage staff and students in colleges and universities up and down the land devouring each issue, for both its editorial content and the highly focussed advertising it carries.

If you, as a reader, have connections in these places do please introduce Direct Driller to them. We would be delighted if they got in touch with us. I can see staff and students being inspired to set up studies on a whole variety of direct drilling topics – drills; fertilisers; organic No-till; crop protection; cover crops; crop termination; crop rotations – and much more. No-till presages a whole new world to research, understand and implement.

The ‘funding’ is already there and I can’t for the life of me see what is holding farm education back, while farmers, such as those featured in every issue of Direct Driller, are doing their own experimenting and assessing. The topic is important for practical farmers today. All involved in farming are well aware that we are at a tipping point. We have perhaps a year, two at most, to decide the direction of travel for our farms. How are we going to make up the financial shortfall? Is our farm on the right course? Given what we know, or anticipate, or fear for the future, can we say with confidence that we are are doing the right thing? Going in the right direction?

As we work our guts to get the harvest in there may well be a moment when farm planning takes a lucid position in our minds. Get a good day when the wheat is fit, the yield better than you dared expect, and in the cab there’s the hum of the harvester engine, the rattle of corn going up the feeder… just right to get those ‘what if’ thinking juices going.

There’s so much to consider, from the present financial position of our farm today, the margins we are making, and the people who are currently involved in the business. Are the important figures for the farm business getting better, or have the numbers showing our net returns, the figure that remains after all the costs are taken into account, been somewhat lacklustre? Here are the warning signs which we can choose to ignore or decide to address, either on our own or with the help of others.

Many will choose the former. There’s nobody they know with the answer, and the problem with experts is that there’s no point in ignoring their advice. Experts can of course be disatrously wrong. The knowledge contained in this issue can only help set you up for better things. Happy reading!

-

To Show or not to Show

By now the show season should be well underway and in some ways it still is. But not in the way we are used to it. Shows like Groundswell, are for many, the highlight of our year. Not just a place to learn, but a place to meet friends, chat about farming and have a beer. The last part particularly appeals to me when attending Groundswell, especially when the sun is shining. However, all is not lost. There is still lots going on. Shows cannot happen, but small one-to-one tours can.

Online shows have become a thing and I suspect they will become a part of all shows going forward. At online shows, you can attend webinars, watch videos and live product tours and speak to exhibitors. It’s all a bit new, but they offer a permanent record of a show that normally just doesn’t exist after a live show.

Farmers can follow up after events have finished, catch up on webinars they missed and keep talking to exhibitors long after the show day has passed. In fact, the only thing missing from an online show, is the live show itself. A live/online hybrid show offers all the benefits of face-to-face contact with all the convenience of being able to catch up with content when it’s convenient to you and see all the things you missed at the live show.

Looking back, there has always been shows I’ve missed due to other work commitments or clashes. Online shows, while also having live content, do offer convenience. Shows are busier in the evenings than they are in the day for instance. Farmers still want to attend, but they can do it when they want to, even from the tractor cab.

Online shows also bring in a wider audience. Virtual Cereals was attended by over 30,000 people on The Farming Forum and this included people from over 90 countries around the world. This is a bigger audience than attends the live show, although you do not have their attention for the same period of time. But if you had both, then it offers the best of both worlds. I have always wanted to attend the No-till shows in the States, but it always seem to clash with other events in the UK.

The thought of being able to attend international events online is really appealing and I’d still happily pay for a virtual ticket. So, to add to hybrid cars, we will have hybrid shows going forward. Welcome to 2020! You can still view Virtual Cereals here.

-

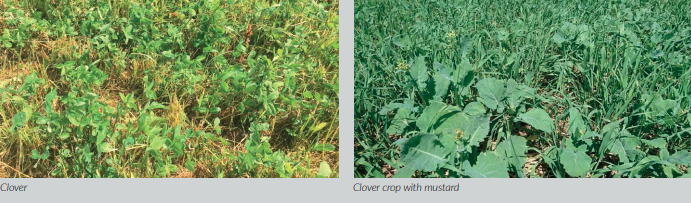

Featured Farmer – James Alexander

Contractor, Litchfield Farm, Enstone, Oxfordshire

Litchfield farm near Enstone in Oxfordshire (owned by Nicola and Kevin Knott) is one of four farms I contract farm (of a total of 1,500 acres, this one is 800 acres). Litchfield is an organic arable farm while the others are ‘conventional.’ In general the rotation is a 2-year ley, spring beans, spring / winter wheat, spring barley, and oats. (In a conventional rotation we generally have a 2-year ley, winter wheat, spring barley, and oilseed rape.)

I’ve learnt a lot from farming organically that I’ve taken into the conventional and vice versa. I have the benefit of both worlds – I can do both and see what works! The conventional farms are all direct drilled – wherever we can we direct drill. The organic Litchfield farm is the complete opposite – we plough, cultivate, and drill. I am focused on trying to find a way to reduce cultivations and direct drill, looking after the soil health and managing weeds as best I can. I’ve been involved in an Innovative Farmers field lab looking at alternative method for terminating cover crops which you can find out more about from the link * below. Various cover crop trials I have been carrying out have led on from this field lab; I have been experimenting with mustard and oil radish (see below), beans, oats, peas, vetch and rye.

We had been stockless for about 11 years but now have 125 breeding ewes which are permanent and being lambed so we can start having our own flock of sheep on the farm (Sam & Charlotte Clarke set up an organic flock and they’re lambing them here – they’ll go on the leys and cover crops). We saw the benefits in 2018 when we grazed 90 acres of cover crops on arable fields which meant we could min till the fields rather than plough them. I grew some of the best oats I’ve ever grown – can’t say it’s all to do with the sheep and cover crops but I’m sure it had a big impact. We have about 180 acres of clover leys in the rotation every year.

Fattening lambs on clover is brilliant – it gives us an easy way of grazing the lambs but then we also have the option if we are putting winter cover crops down, to graze them with sheep – and if it means we can min till instead of ploughing, all the better! Blackgrass is worse in some years than others – it depends on the rotation and the fertility we have in the soil. We sheep, top, sheep, and top leys and leave as a mulch, the aiming being to turn clover leys without ploughing. In addition to the farming I also manufacture and sell no-till drilling equipment.

Sustainability in practice:

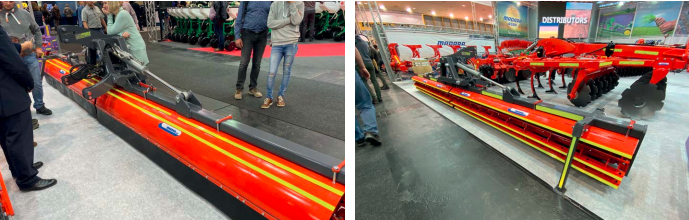

Using a roller crimper to improve weed management and soil health

I am very keen to reduce tillage in the organic system – having seen the benefits in the conventional system, so I direct drill where I can. Cover crops are an essential part of that system but I need to find a way to control them without using glyphosate. I have therefore been developing a UK-focused roller crimper which essentially breaks the stems of the cover crop when it’s going to seed (it’s weakest point) and then can kill it. This is a key part of the conventional farms but in the last few years I’ve been experimenting with how I can make it work on the organic farm. Two years ago I tried rye and vetch and found that it was quite challenging to kill the vetch – it took multiple passes, but I am hoping to develop this system…

See the scrolling images above to view a field of vetch at various stages of crimping.

Watch the video footage below to find out more of what James has to say about using a roller crimper to manage cover crops, assist with direct drilling, and improve weed management and soil health.

Permanent cover crop of white clover

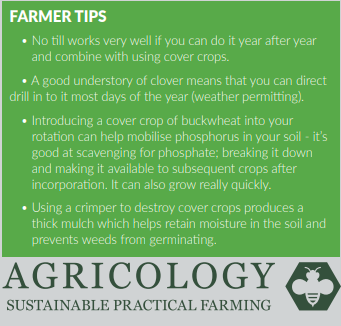

James explains: “In a field after the spring barley has established, we’re undersowing it with a crop of white clover (small variety). The idea being, similarly to another trial with mustard and vetch, that we keep an understory of white clover permanently in the bottom of the crop which will then allow us to direct drill the following crop back into it. I’m looking at this as part of a field lab I’m involved in that’s exploring using a permanent living mulch understory in low input / no till systems… By having the clover there, we also have a permanent source of nitrogen so we mightn’t have to do our 2 / 3 year red clover leys which we’re losing a bit of production with. It means we can keep cropping, and hopefully produce some better quality crops and yields too.

We plan to direct drill oats into it in the autumn. We could mow and drill into the clover or graze it hard with sheep then drill into it. With having an understory of clover, if it’s a good cover, it means I can just about drill into it any day of the year. We’ll learn over the next year or so what works best; if we put a spring crop in, we can leave the clover over the winter and drill the spring crop beginning of March so it can get going before the clover does. We’ll probably establish the clover when the spring barley is at a couple of leaves stage. I’m not sure yet if we’ll put the clover in with a drill or spread it and grass harrow it; it will depend on the conditions at the time.

Buckwheat to help with dock control

James has been growing buckwheat for two or three years to try and help with the dock problem. Buckwheat is thought to emit allelopathic chemicals that can help control docks (see information in relation to another field lab here).

He says: “Our initial idea in relation to dock control was to keep cultivating, which accelerated the problem! Last year (2019) was the third year we’ve put a buckwheat crop in over the summer straight after the spring barley. We direct drilled the buckwheat into it and have been ploughing the buckwheat in green before it dies which helps stop the docks growing. We think we are seeing less and less docks. We’re home saving our own buckwheat seed to make the job cheaper. Higher seed rates (thicker crops) do better. Buckwheat lifts P and K (phosphate and potash) from deep down in the soil which is another bonus. It is also twice as efficient at taking nitrogen into the plant. We put buckwheat in with our rape as a companion which we have found helps control flea beetle. The flowers are also great for beneficial insects.

MOTIVATIONS:

One of my main motivations is to look after the soil – our most precious resource. In the organic system, fertility building leys help protect and feed the soil but also help us control blackgrass – using a 2-year fertility-building ley by mulching. On the farms managed conventionally, direct drilling and no till works very well if you can do it year after year and combine with using cover crops – winter cover crops or 8 week cover crops during the summer – it gives you a lot back. I am aiming to go reduced tillage or direct drilling in the organic system. The farming system needs to be reliable and viable – for me and the owners.

We’ve started to feed our soil with some molasses – we trialled it in 2018, and in 2019 we have used it on a wider scale. On the conventional farms we’ve been able to cut fertiliser back by 5% with using molasses. The mollases makes the bugs in the soil happier; they’re working for us and help us to look after the soil. They also help us utilise the fertiliser we’re applying better on the conventional farms. With good soil comes less pests and less weeds, which can only be a good thing.

We generally direct drill our fertility building leys (but min till some). If we can do more no till, it would undoubtably be more weatherproof and soil friendly than ploughing. This last year we have had fields that have been ploughed and cultivated that we couldn’t touch because they were too wet, whereas with fields that had been direct drilled, we only needed the surface to dry off.

In the video clip here James touches on some of the learnings from both the organic and conventional way of farming (apologies for the wind interference!).

-

Agricultural Ethics: A Decision Making Tool For Farmers? (Part 1)

Written by Ralph Early

”No one will protect what they don’t care about; and no one will care about what they have never experienced.” David Attenborough.Not so long ago, wildlife in Britain was so much more abundant than it is today. Back in the 1960s, in early summer, one could walk the fields of most counties from Land’s End to John O’Groats and quite literally trip over wildlife: rabbits, hares, pheasants, partridge, and many other species hiding in knee-high grass.

A stroll through meadows carpeted with stunningly beautiful wild flowers would fill the air with butterflies, as once disturbed they departed the sweet nectar in one location to alight on blossoms in another. At night the same meadows would be filled with moths, swarming uncontrollably to the light of a torch. For anyone who remembers such experiences, this was Britain’s countryside at its most glorious. Sadly, in 2020, that world no longer exists, which is an undeniable calamity. The loss of so much of Britain’s wildlife over the last half century, and with it many irreplaceable ecosystems, undermines the capacity of Britain’s natural environment to support planetary ecosystem services.

This is a moral issue of immense importance to the future of humanity and the innumerable species with which we share the planet. It is also, distressingly, an incontestable catastrophe for young people today, for they will never experience British wildlife of the quality and diversity routinely encountered less than a lifetime ago.

They will never know nature’s wonders common to the Britain of their grandparents and greatgrandparents. A land where skies were filled with birds, hedgerows buzzed loudly with insects, and countless small mammals, reptiles and amphibians scurried in search of food. That world has passed into history and tragically may never return.

The past is the key to the future

If we are wise we will learn from the diminution of Britain’s natural heritage: a disaster that was so clearly avoidable, but which we chose not to see even as it was unfolding. Indeed, we have a moral duty to learn from it not just for ourselves, but for future generations whose rights we may deny through our own thoughtlessness and selfishness. We must learn from the past and in doing so must find ways to chart an ethically sound and ecologically sustainable course for the future. In this we should recognise that the word ‘sustainability’ is itself morally instructive. Sustainability as a term is now part of common usage in the agrarian lexicon.

This is a positive sign. It confirms recognition that we are prepared to admit that aspects of farming practice, as we have employed them for decades, are in fact environmentally harmful.

They are demonstrably unsustainable. Importantly, by being prepared to admit we got things wrong, we express understanding that we know we must change the way we farm. We also need to change the way we think about agricultural food production such that we find better ways to work with nature, not against it. In this respect we need to dispose of irrational perspectives, such as the perverse idea that by divine moral right mankind has dominion over nature. Such archaic notions are embodied in many of the farming and land use practices that created the problems we now face. If we are to manifest a truly sustainable future, a paradigm shift and definitely an ethical shift in our thinking about food and farming will be needed.

Happily this is underway, as evidenced by many practical actions being employed by enlightened, progressive and morally aware farmers, such those using zero tillage methods to restore soil quality and fertility. It is also seen in the way ethical thinking is being used overtly and in less obvious ways to guide agricultural food production more broadly. Notably, we are witnessing the development of agricultural ethics as a specialised branch of moral philosophy, and a decision making tool, accessible to farmers, agrifood businesses, policy makers etc.

This article is then the first part of a twopart article on agricultural ethics which, it is hoped, will be of particular value to everyday farmers as the professionals to whom we remain constantly indebted for keeping us fed. The aim of the article is to explain something of the concept of agricultural ethics and how it can be of practical value. However, before we immerse ourselves in ethical theory in part two, in this part we should first reflect a little on the history that has brought us to this point.

Change and acceleration

Change is inevitable. During the last century it has occurred at an almost unimaginable rate, particularly in the industrialised world. Since the end of World War II, significantly as a consequence of Norman Borlaug’s Green Revolution, British agriculture has been transformed almost beyond recognition. Britain’s rural landscape began to change markedly in the 1960s, with a pace that accelerated through the 70s and 80s. Post-war agrifood policies aimed at enhancing Britain’s food security were partly responsible, as was the EEC’s Common Agricultural Policy which aimed at maximising agricultural productivity.

These factors catalysed a momentous shift in perspective with respect to the purpose of farming and, significantly, the end of the 1960s began to see the transference of elements of farm decision-making from farmers themselves to a new breed of off-farm, agricultural specialist, the farm consultant. These advisors employed by agribusiness corporations, banks and ADAS (Agricultural Development and Advisory Service), among others, introduced new perspectives to British farming which centred on ‘efficiency’, ‘productivity’ and ‘profitability’. These terms became watchwords for the industry.

But nature is not efficient, productive or profitable in any way that agricultural economists, especially ones wedded to the neoliberal capitalist ideology of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman that now shapes the British economy, would appreciate. A consequence of the development of agriculture as a movement centred almost exclusively on productivity, efficiency and profit, was that big came to be regarded as beautiful. Small-scale, mixed farms were regarded as a thing of the past.

Large farms grew larger, increasingly focusing on fewer or even single enterprises, and monoculture agriculture became the new norm. Such farming was prized because it was modern. It represented a vision of the future, communicated evangelically to aspiring young farmers in colleges and universities throughout the land, with the support and endorsement of burgeoning transnational agri-business corporations. As British farms changed so farmers, once steeped in the traditions of preceding generations and a sense of spiritual indebtedness to nature and the land, were transformed into agricultural technologists. A new breed of farmer had arrived. The farmer as expert in distinct and even separate types of agricultural food production. No longer the generalist, increasingly the specialist.

As farming has become more specialised, a relatively small number of major agri-business companies have achieved significant influence over the British agricultural sector.

At the same time, the supermarkets have ensured that they are the main points of access to the food marketplace for British farm produce. Power imbalances are now common within the food system and the pressure to survive is a constant source of anxiety for farmers, often exacerbated by the lack of morally just financial rewards. For some, solutions lie in the application of new technologies, for agriculture itself is a technology, and in this they may be right. At least in part.

Experience reveals, however, that both science and technology often have the tendency to advance faster than the wisdom required to regulate and control them. New technologies such as precision farming, genetic engineering and CRISPR-Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and the CRISPR-associated enzyme, Cas9) will undoubtedly play a role in the development of British agriculture, as will other technologies. But if farming is to become truly sustainable and, importantly, ecologically benevolent in the way it serves the needs of humankind today and in the future, it will need to embody moral values based in a deep respect for ecology and the workings of the natural world.

Such values will inevitably be informed by the theory and practice of agricultural ethics which, necessarily, will demand that all who regard themselves as agriculturalists, whether directly involved in farming or employed in ancillary and support sectors, remain conscious of Ernst Friedrich Schumacher’s words, “Modern man talks of the battle with nature, forgetting that, if he won the battle, he would find himself on the losing side.

Old problems demand ethical solutions

As farmers work to survive in an increasingly competitive world they quite reasonably seek opportunity in innovative ideas and technologies. However, while novel ideas and technologies may yield many benefits, they may also entail unintended consequences which bring to the fore a variety of ethical dilemmas. Indeed, the central moral issue faced by all farmers is found in the fundamental duality of doing good through the production of food yet, at the same time, minimising and ideally preventing the harms that agricultural practices may entertain.

For instance, over the last 50 years agricultural policy decisions, combined with market forces and innovations by the agricultural machinery and agri-chemicals sectors, have triggered an increase in the size of farm machinery with promises of continually increasing efficiency, productivity and profitability. This, though, has generally been associated with the elimination of hedges and other wildlife habitats in the UK to create larger, more efficiently managed fields with the unintended consequence of a concomitant decline in wild and farmland biodiversity.

Ploughing and the use of heavy machinery, once considered a standard practice, is now known to cause soil erosion and the release of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, while artificial fertilisers accelerate the loss of soil quality and organic matter, catalysing the breakdown of aggregate structure so increasing erosion and loss of top soil. Additionally, phosphate, a constituent of synthetic fertilisers and organophosphate pesticides, causes fresh water eutrophication while nitrogen from fertilisers causes sea water eutrophication.

Research, reported in 2014, suggests that the quality of British farmland soil is now such that only around 100 harvests are likely, which is why the improvement of soil quality has been set as a priority objective for national agricultural policy.

These are just a few of the issues that farming faces and which raise numerous questions of an ethical nature. Indeed, many are issues that may best be understood by means of an ethical lens, so helping to determine the route to genuinely sustainable and regenerative forms of agriculture.

A moral compass for farmers

Ethics is concerned with the moral values and principles that govern human behaviour. It deals with concepts of moral goodness and moral evil, perhaps more easily understood as moral badness, as well as with human actions framed as what is either morally right or morally wrong. Agriculture yields many benefits for humankind, being the source of most food as well as e.g. biofuels and fibre.

But the practice of agriculture can itself present a range of moral concerns, simply because it has the potential to cause both benefits and harms.

For instance, the loss of wild habitat to agricultural food production has already been cited as a moral issue and one that raises many questions about the moral rights of the environment and biodiversity. The use of agri-chemicals demands ethical consideration of the utilitarian balance of benefits versus harms with respect to possible negative externalities, e.g. effects on pollinating insects and the health of farm workers and consumers. Farmed animals, as sentient beings capable of experiencing pain and suffering, deserve for valid moral reasons to be respected and cared for appropriately. These are among many of the moral issues embedded in the practice of agriculture which, because of space, we cannot appraise here but will do so in part two.

Agricultural ethics is then an applied subject of practical value to contemporary farmers who, unlike preceding generations, face a diversity of existential threats which must be resolved if farming itself is to be sustained long into the future. An inescapable and often uncomfortable truth is that many of the challenges that farmers face today are rooted in the practices of agriculture developed in the last 100 years or so, as well as in the general industrialisation that occurred during the last two centuries. Such challenges are epitomised by the problem of anthropogenic global climate change. Solutions to most agricultural problems will doubtless be found in the sciences and technology. But as farming redefines its path to an industrious and ecologically sustainable future, we can be sure that agricultural ethics will provide the moral compass required to navigate the journey and ensure safe arrival.

-

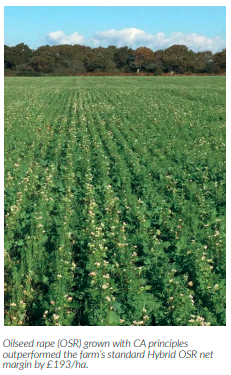

The Path To Conservation Agriculture

Written by James Warne, Soil First Farming

Social media can be a useful source and tool for knowledge transfer, discussion around various topics etc. But far too often it can also be the source of misinformation or confirmation of prejudice, particularly where the discussion deviates from received wisdom. I am referring here to agriculturally based discussions around the topics of Conservation Agriculture (CA), soil nutrition, agronomy etc. There are some common recurring themes which need addressing because all too often much of the advice given is in my opinion flawed for many and various reasons. In this article I will touch on a few of these questions…

‘My soil is not ready’

‘My soil is not ready’ is a common retort. When will your soil be ready? Next year, in two years or five years? By what criteria are you assessing your soil to make this statement? To paraphrase Morrissey, my normal response to this question is how soon is now? The point being that while you continue to cultivate you are slowly, but surely, moving your soil further away from that point of ‘being ready’, whatever that is. Cultivation, while undoubtably bringing some short-term benefits, also brings about its own set of problems; reduced porosity over the longer term; oxidation of organic matter; decimation of worm populations; increased risk of run-off and soil erosion with the consequential issues of diffuse water pollution from fertiliser and pesticides, to name a few.

The path towards Conservation Agriculture can start now if you want it to. Every year of dither and delay is another harvest where you didn’t try something new, and maybe didn’t benefit from the potential to reduce establishment cost. One certainty is that agricultural production in the UK is sliding down the political agenda which will result in reducing financial support. What is apparent from the last few months is that food security is not on the current governments agenda unless it is by means of food import. Whichever way you look at it farming is going to have to work hard to cut its production costs to remain profitable.

So, back to the original question when will the soil be ready? The questions you need to ask yourself are; how did the field in question yield at the last harvest? If the answer is ‘as well as could be expected and comparable to other fields’ that’s a good starting point. Have you trafficked said field with harvest operations or post-harvest operations such as muck spreading or baling? And finally, have you taken a spade out and looked at the soil structure? If you are happy with all the above questions then now is a good time to start changing the system. If you at all uncertain then call in a third-party opinion.

This soil probably isn’t ready for no-till.

You can of course reduce the risk by not converting the whole farm in one year, consider implementing the system across a whole rotation or maybe two rotations. But do not fall into the trap of opportunistic direct drilling as a way of reducing establishment cost because you will never realise the full benefits of the system. Each subsequent cultivation effectively resets the clock and you end up having to travel through the troublesome early years of soil cultivation ‘cold turkey’ (see below) each time. You haven’t reduced the fixed cost structure of the business because you have been holding onto cultivation equipment that could be sold.

‘I have the wrong type of soil’, (it’s too heavy, too light or contains too much silt etc, etc)

Any soil type can be successfully managed through a CA system but it’s true some demand a lot more attention than perhaps others. Light sandy soils with very low organic matter will have a tendency to quickly slump and consolidate, this also applies to soils with a high silt content. Much care has to be applied to field operations only happening when the soil is able to carry the machinery.

Cover crops and cash crops with good rooting characteristics should be grown in the early years as this is what is going to give the soil structural and physical stability. I cannot stress this enough, it’s so important to avoid any performance drop which is one of the main obstacles to adoption. As far as plant growth is concerned the important factor is the pore space characteristics are strongly influenced by the stability of the soil structure when wetted. The presence of earthworms, plant exudates, humus and plant roots themselves all act to encourage the formations of soil structures stable in water.

Clay based soils will have a degree of natural structure provided by the clay colloid, whereas the silts and sands will not have much clay and little organic colloid to help with structure. These soils are often easier to manage in the earlier years, especially where they are calcareous and therefore will have a good calcium carbonate content. As alluded to above the key to success is the early introduction of large amounts of carbon either by chopping residues, spreading manures and compost etc, and by growing cover crops. Doing all of these in the early years is necessary to stabilise the soil structure, to encourage natural porosity and fertility.

‘I am looking at buying a disc drill’

Many seem to be obsessed with moving the minimal amount of soil and consequently are looking at disc drills because they are all over social media. Yes, this is true, disc drills can move very little soil and that can be a good function in some circumstances, but not always and certainly not at the beginning. In the early years the soil will be in a state of cultivation ‘cold turkey’. Take away the cycle of annual cultivation and the soil will start to slump, consolidate and loose porosity before the biology and chemistry starts to sort out the physical stability of the soil and increase the porosity once again. This can reduce crop performance in the early years, this is cultivation cold turkey. Tine drills by their very action will create a little tilth and give a better result more often than not especially when soils are dryer or wetter than ideal.

Tine drills can also drill through green cover if judiciously managed, and they will certainly drill through chopped straw better than any disc drill. The fallacy of only using a disc drill has been shown time and again over the winter months. Poorly established or failed wheat crops resulting from using disc drills on over-wet soil can be seen all over the country. Where tine drills have been used the results are considerably better, but still not perfect. Even this spring it is very easy to spot crops which have been disc drilled where the slots are opening as the soil dries revealing the plant roots to the air and increasing the rate of soil moisture loss. When I mention tine drills I am not referring to those with any form of leading leg, these are strip-till drills and should not be confused with a genuine no-till tine drill. Leading leg strip-till drill designs move too much soil to be ever considered for a genuine CA system.

Don’t believe everything you read on social media (unless it’s about government hypocrisy), get a second opinion, or visit someone who’s already doing it. No-till is part of the solution, not part of the problem.

-

Why Do We Have To Treat Our Soils Like Dirt?

by Nick Woodyatt, Soil Fertility Consultant at Aiva Fertiliser

Normally when starting an article there is much gnashing of teeth and wandering around the garden, or pub in my case, deciding on how to help and enlighten our industry (hopefully). But seeing as it did not stop raining during the autumn/winter, on this occasion the decision was somewhat easier. My town should have been re-named Upton under Severn. On my rounds I saw two four-wheel-drive tractors tied together pulling a plough through the field which looked like toothpaste and all eight wheels were spinning as they pulled themselves down onto their axles: really. Funnily enough the managers of this farming area were having a heated debate at the same time on whether to use a direct or strip till drill which simply amazed me.

We all know that if we lose Glyphosate then getting to a good position [soil wise] for direct drilling is going to be so much more difficult, but not impossible. What is perhaps now becoming obvious, is the effect that climate change will have on this method of growing, with longer and wetter periods, and yes, I do realise now we’ve gone from one extreme of constant rain to the next which is as dry as a party in a nunnery, but that still has the same effects.

On my farm walks I saw the relentless tapping of billions of raindrops on the soil surface produced an 80-100mm cap that has the consistency of wet play-dough which, is either going to cap over growing crops or produce an airless situation in to which seeds will be put. Indeed, I watched seeds direct and strip drilled (on good soils) and I have had to ask the question, ‘Why’? The direct seeds are firmly encased in a solid wall of mud so as they chit, they will more than likely rot. The strip tilled seeds are more of a surprise.

I tripped over this problem in the wet autumn when I was told that my bacterial application had stopped having the desired effect on clubroot in cauliflower. When I visited the problem it was plain to see that the soil wasn’t ready for this method of drilling and the drill had in effect formed shallow drains across the field, therefore producing an anaerobic environment for the soil life hence allowing the harmful anaerobic pathogens to run amuck. Now if it had stayed like that I wouldn’t have been too alarmed, but since then, I have noticed that the lifted rows left by the strip till are overtly wet compared with the surrounding soil regardless of how good the surrounding soil is. The phrase that we earn the right to use any specific piece of machinery is oh so right.

The importance of air

This is leading me to suggest we need to see that there are times when sowing isn’t going to work (difficult to say the least) and we need to stick to the rule that the soil needs what the soil needs, to get air into it. If you can’t find it in you to see that I may have a point then get a friend to strangle you and see how long you can last and no, there is no difference (only in time). We discuss soil, nutrients and where unenlightened, agrichemicals, but how often do we look at air and its importance. Without a free and open soil structure everything else starts to fall apart and your inputs will rapidly rise whist your profits rapidly fall. A perfect soil contains 50% air, and this impinges on so many plant processes and as farmers who are or considering min/no till we really need to understand that this allows:

• Fresh air into the soil where bacteria such as Azotobacter can convert gaseous N into a plant available form saving you money.

• Better penetration of applied nutrients in whatever form they are applied to avoid this surface rooting that we see in many crops.

• Carbon Dioxide from bacteria from the soil up into the leaf increasing photosynthesis and increasing your yield (Why do you think the stoma are on the underside of the leaf?) • Roots to penetrate deeper to get to more nutrients allowing you to reduce your inputs and this increases drought resistance.

• Better roots which allows more sugar release into the soil which feeds the soil life which in turn feeds your crop and resists disease therefore less inputs (the circle of life).

• Better penetration of earth worms who do so much for you free of charge that it is one of the wonders of the world why we try to kill so many (oh, I remember, it’s the profits of the chemical companies, silly me)

I could go on and on, but I think you get the message, start with air and work out from there as against start with Nitrogen and work for the chemical companies. However, as we have to work with excessive wet and excessive dry periods is there anything that we can do to alleviate the situation and of course the answer as always is yes.

Many farmers who are going down the min/no till route are doing it because they feel a moral duty to improve their soils for future generations and those like me, fancy making a profit occasionally. Those who are doing it just as a Black Grass control have stopped reading ages ago.

It’s more than the right products

Firstly, let’s make it clear that to improve a soil for both dry/wet periods isn’t just a case of buying the right products as some want us to believe. One farmer has been told that by applying a good soil wetting agent excess water will drain away; this was said to a farmer whose soil was under water so we did have to wonder where the water would go. There are any number of ways of moving forward and I am going to mention my friend Tim Parton who was `Soil Farmer of the Year 2017’, `Arable Innovator of the year 2019’ and is `Sustainable Farmer of the Year 2020’ and has transformed his soils over the last 10 years just by judicious use of cover crops which absolutely amazes me on two fronts. The first is that Tim is a farm manager so has treated soils with a loving care even though they are not his. How can you not respect a man like that?

Secondly there are many salesmen, sorry, agronomists, who claim cover crops are a waste of time. Tim now uses a low input system so that a bad season doesn’t throw him into pits of despair and he can afford to wait to sow until conditions are right, like me believing that a well planted spring crop will outperform a badly planted winter one. If you get chance to hear Tim speak it is well worth the effort as he explains how regenerative farming starts and ends with looking after the soil, as well as drastically reducing Nitrogen inputs which then allows everything else to work. I have enjoyed working with Tim again this year to make sure that we keep Nitrogen levels low to remove the need for PGR’s or fungicides so smiles all around, well apart from a few obviously but they have had their pound of flesh many times over.

– Please note that I am not making light of this as depression is a major part of our industry so let’s keep an eye on neighbours and colleagues –

Along with cover crops we are seeing an increase in digestate use and any number of other manure wastes, although we do need to look at those to protect our soils for the future and to make sure they don’t become toxic in drier conditions.

My point here is that for every 1% of organic matter that we can increase in the soil we will get an extra 17,000lts of water available to the plants plus drainage is improved as airspaces remain airspaces, except that is in severe flooding. I know that sounds stupid as we were under the damn stuff but as soon as it goes dry, we will all be saying, ‘Why don’t we store more of the water that is around in the winter?’, won’t we? Also, organic carbon, not matter, allows the soil to breathe even when it is very wet (not flooded unfortunately).

Getting better roots

I have never believed that there is a time when you can’t learn something which is why I don’t like the term ‘expert’ which denotes a closed mind. On my travels I have seen things starting to change on regenerative farms where limited tillage is the name of the game:

• Far better plants where no seed treatment was used allowing better germination and faster and better root penetration.

• An amazing root explosion where natural microbial counts were augmented with added brews of bacteria. In one trial, noted at the end of January, the seed in the normal field was on its third leaf but only had a poor shallow root. On the adjacent field under the same conditions but with my added seed drench (bacteria, humate and Silicon), we had similar tops to the plants, but the roots were over 300mm deep (that’s a foot to my dad!)

• Superb root systems where digestate and slurries are buffered with a Humate such as AF Nurture N from Aiva Fertiliser (see, I told you I was a salesman). I have digestates that kill seeds if applied directly to the seed but work wonderfully when added to a Humate.

As far as a way forward is concerned, we need to feed what we have in the ground growing as it has very little in the way of available nutrients although I do not agree with flying around with Nitrogen as that is just meat with no gravy, leading to empty calories and the need for fungicides. Try spraying with Phosphorous, micronutrients and Silicon to prepare the plant for the Nitrogen otherwise you will have to use agrichemicals. I would say not to go onto the ground before it can take you, but I know a waste of breath when I see one.

Apply the N with AF Nurture N (me again) so that you can reduce the amount you use by 30% with no visible signs of a yield difference but a major step on the way to better soils and higher profits. With Boron being an issue I believe that we should use less but more often otherwise it can get a bit toxic. I have put Boron on this year in lower levels but more often as little and often always seems to pay dividends for me.

Controlling disease

Amongst regen farmers we are starting to see that getting the soil healthy and balancing and reducing nutrient input can have a huge difference on disease control.

Where we use a biological seed drench and a microbial package as a foliar programme along with micronutrients in low/no till systems, we use no PGR’s or fungicides which is a major target of all my farmers. The overuse of chemicals has left us with monsters such as Fusarium and Cabbage Stem Flea Beetle which now we must deal with. Our biological system has had a dramatic effect of Fusarium and other diseases with really low rates in the seed when tested so, there is another way. Following the wet period, I noted huge amounts of Phytophthora on farm which could be the next monster to attack us, although luckily the healthy biological system used by many regen farmers actually stops this problem so we will be able to explain this to more conventional farmers when they are scratching their heads so try not to look too smug.

So, do we have to treat our soils like dirt? Of course not, we just have to grow well and work with nature and not fight it!

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

THE FUTURE LOOKS BRIGHT

The past few months have been challenging for all of us. We were gearing up for a remarkably busy spring with more demonstrations than we could have imagined. However, the arrival of the Coronavirus and the ensuing lockdown meant early on we took the decision to cancel all Spring demos for the safety of our employees and the farmers we would have been demonstrating to.

All was not lost though we were still using the Virkar on our own farms and following on from the success of establishment in the autumn. We were looking forward to really testing it again this Spring and the results have been outstanding.

New for 2020

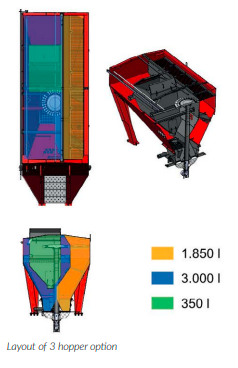

The Virkar Dynamic DC has had a few changes and new options for the 2020 season. It is now available in widths up to 7 meters, available with 3 hoppers, hopper extensions, and auger feed loading. As well as the new front cutting disc which really improves the drills capability in heavy chopped straw ground. There are now the options to be able to put tramlines in, and a factory fitted camera system with hopper camera and rear camera which improves the user experience. Also, we have developed over the past few months a more resistant spring compensator in the coulter, for heavier ground meaning you divert more pressure to the seeding tine and closing wheels meaning easier slot closure on heavier ground.

The new normal

I think it is now clear to see that our weather in this country is becoming harder and harder for us to achieve what we want as farmers. Months of wet followed by months of dry, means crops have been under a lot of pressure.

Having direct drilled Spring Oats Spring Barley & Spring Wheat, into a wide range of scenarios such as 5 ft tall buckwheat, oats, and phacelia cover crops, we were extremely impressed in how the drill dealt with the conditions. The ability to conserve moisture through No-Till in the Spring is becoming crucial. All our Spring crops that were direct drilled look extremely healthy and strong. Being able to drill the field using only 2.5 litres of fuel an acre and seeing a brilliant crop emerge knowing you have saved £25/30 acre over the previous system is a good feeling.

One Year on

Having now run our 6 Meter Virkar Dynamic DC for a whole season. It is clear to see that it has exceeded all expectations. It truly is one of, if not the most versatile & simplistic drill to operate. The results and interest we have received has been very encouraging.

Moving forward with the uncertainty around what the future holds for our industry, I think more so than ever NoTill is an attractive avenue to go down. For us with our own farming operation the Virkar has allowed us to significantly reduce our establishment costs whilst maintaining yields.

Looking ahead

We are already preparing for the Autumn demonstration season and hoping this time we can finally get the drill out and about on farms. We have had in the past few weeks and moving forward plenty of farmers visiting us seeing the drill first hand and having a tour of our farms and crops that have been drilled using the Virkar , they leave very encouraged by what they have seen.

They say a lot can change in a year, from seeing a video of the drill on YouTube, to now having drills out working across the UK. This machine is now a key part of our farming operation, by future proofing our business by ensuring we have the most cost effective and efficient system in place for crop establishment. We cannot wait to see where the next 12 months takes us.

New drill on the Horizon

New for 2020 is the direct disc coulter version of the drill. The Dynamic D has been a project that Virkar have been working on and thoroughly testing in tough Spanish conditions for 2 years.

The coulter design means it can mount into the same frame as the Dynamic drill meaning you keep the modular design, widths from 4.5 to 7 meters will be available with either 19 or 25cm row spacings. The coulter arms are maintenance free, sealed bearings and bushed. The coulter design means you get 35cm of travel for contour following, on the move coulter pressure adjustment, and only one manual adjustment per coulter leading to quick set up time in the field. Again, the drill can be specified with 3 hoppers and various other options.

-

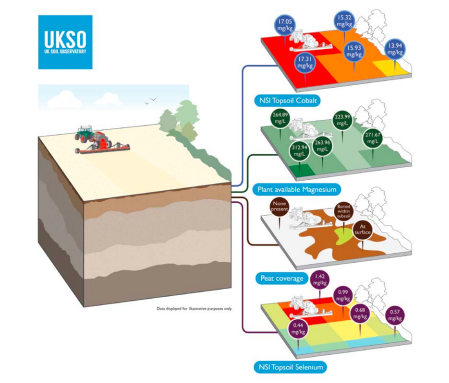

New Horizons For – Soil Research

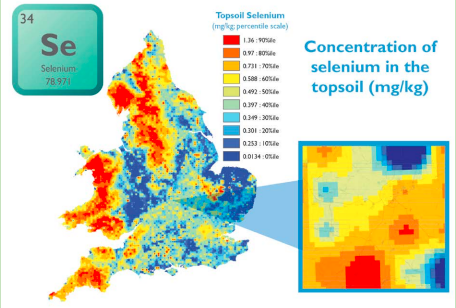

The UK Soil Observatory (UKSO) is an award-winning and free-to-use online service that enables everyone to view soil datasets from nine research organisations. Russell Lawley (Geo-Properties and Resources Team Lead) from the British Geological Survey explains how the resource has developed to provide significant benefits to the agricultural sector, what information you can expect to find, and how UK farming will play a major role in soil research in future.

The importance of soil to the UK and its role in supporting our environment and livelihoods will likely be among one of the most critical topics of the next decade. There is still some way to go, but soilhealth and resilience are at the heart of the new agricultural policy, and research investment from commercial and academic resources is now rising. As scientists, we are continuing to sound the alarm about the important connection between soil health, sustainable agriculture and tackling the climate crisis.

Each year, more attention turns to the important relationship between soil and climate. The availability of soil data and the significant increase in technology in agriculture, has been key to the transformation of people’s perceptions and understanding of what goes on beneath our feet. The ethos behind UKSO is that no one should have to start with a blank map when it comes to soils information. When UKSO started in 2014, it had a tiny number of users, accessing a handful of archived soil maps.

As well as data from the British Geological Survey, other partners contributing include the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), Center for Ecology and Hydrology, the James Hutton Institute, Cranfield University, Rothamsted Research, AgriFood and Biosciences Institute, Forestry Commission and Forest Research. What began as a platform that caters for a wide audience, aiming to provide everyone with free access to soils data for the purpose of educating people about soils, has quickly evolved for use by key industries such as agriculture. Today, we are approaching 190 online maps – many with regional, if not national coverage – and the data is being accessed by a wide range of users every week. This includes farmers exploring their options to move into viticulture or forestry, to agronomists and contractors checking the ‘lie of the land’ before considering new territories.

We provide mapping for England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland with access to over 180 layers of data covering physical, chemical and biological characteristics including type, texture and grain size.

We are also providing more services for landscape domains and hydrology. Using UKSO, it’s possible to explore soil carbon, soil chemistry, pH, moisture, texture, type and agronomy, even upto-date surface slope data. The online maps can all be viewed on the UKSO platform ‘Map Viewer’ via mobiles phones, tablets, and desktop.

Many farm-mapping software applications can also use the web mapping services directly – for increased convenience, and better integration into farming systems. It also offers access to a number of resources through the UKSO website, including a series of quick-access static maps and exports from UKSO’s Map Viewer which are coupled with contact information and usage. It houses policies and guides for agriculture and industry and a selection of other useful apps and services which can help you find out more about soils in your area. These resources are only likely to grow in future as the service evolves.

What can you do with UKSO?

Over 180 layers of data can be viewed using the UKSO map viewer, which can be used to gather information about soil type, texture and grain size and a wide range of physical, chemical and biological properties. Users can also view the data within their own mapping software or apps. This includes Soilscapes, a 1:250,000 scale, simplified soils dataset for England and Wales which shows, in simple terms, what the likely soil conditions are at any point in the landscape by reference to one of 27 different broad types of soil. The users can benefit from extensive data about their soil chemistry as UKSO draws together data from the National Soil Inventory (NSI).

Other features include soil biodiversity data relevant to topsoil microbes and organic carbon concentrations, as well as topsoil nutrients, soil moisture and soil PH data from the Countrywide Survey (CS). This includes CS topsoil bulk density data, representative of 0-15cm, and maps covering Great Britain’s BioSoil pH data for a range of soil depths.

Planners and land managers can even benefit from surface data detailing for example, ruggedness, slope, and profile curvature derived from Ordnance Survey (OS) Terrain 50 elevation data, a dataset representing the physical shape of the real world. You can also access an archive of soilrelated resources, news and information such as soil apps, publications, events and research projects. Recent updates and future developments Right now, a key focus for UKSO is releasing more data for the agricultural sector. In January 2020, we launched new maps relevant to mixed-arable and pasture farmers directly relevant to ruminant health. The maps show regional levels and availability of the element magnesium in soil.

Low magnesium status (hypomagnesaemia) gives rise to tetany, or staggers, in ruminants. These conditions are remarkably widespread among ruminants in Europe, often with high fatality rates affecting business profitability. The data is designed to help understand the natural availability of these minerals in soils, and their likely uptake into plants. It can also inform the need to plan for supplementary feeds, sourcing grazing or forage from higher magnesium soils, or just for monitoring cattle if necessary. The research was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and the Natural Environmental Research Council (NERC). Both organisations have significant research areas devoted to food security issues. Using UKSO as a readily available toolkit for such data, will continue to ensure that industries like agriculture can benefit from high-quality research as quickly as possible.

How will UKSO adapt in future?

For agriculture, the upcoming Environmental Land Management scheme will see many changes in how we value our environment. With an increased awareness of soil health and resilience, there are likely to be inevitable changes to environmental regulations. A key part of future work for UKSO will be to provide an increasing array of data to support decision-making and compliance with changing environmental regulation. UKSO has already started to respond to such changes. We are currently trialling national maps of slope, so that agronomists who are preparing for changes to agricultural run-off regulations, can start to assess which parcels of land may be increasingly affected by the new rules.

We have responded to the renewed investment in peatland restoration by providing higher resolution peat mapping across Great Britain. The aim is to enable users to assess how much peat is present (or securely sequestered beneath it), assisting effective and responsible land management. Whilst traditional soil maps are still the most popular layers being viewed, demand has increased for datasets that answer specific questions relating to the land. We’re keen to ensure the service remains highly responsive to user feedback, who really are at the heart of what UKSO provides, and will fuel its future capabilities. Current feedback is pointing towards a greater demand for ever-higher map resolution and more frequent updates and that’s something we’re working hard to address.

Over the next 12-24 months, we anticipate that UKSO partners will be refining a number of other datasets. These include:

• improved texture descriptions for percentages of clay, sand and silt via laser-granulometry of 72,000 soil samples;

• Revised soil and sub-soil descriptions;

• New, very-high resolution, terrain datasets derived from Environment Agency Lidar survey;

• New trial models of soil erosion and soil compaction susceptibility;

• Improved options for using citizen science (the agricultural sector sharing their experience of their soils) and the potential for storing more data from soil sampling and field trials.

How you can help UKSO to grow

We are keen to continue learning about the needs of the agricultural sector and the specific needs of the direct-drilling community, who have already implemented changes to their land management to help improve soil resilience. We provide a contact form on the UKSO website (ukso.org/contact) where you can formulate your feedback and help to steer the development of the UKSO.

In particular, we would welcome thoughts from the industry such as:

• The soil or landscape datasets that you think should be in UKSO relevant to your sector, but might be currently missing.

• Soil or landscape datasets in UKSO that you find useful, but would like to see updated or improved, which ones and how.

• Suggestions for new datasets, or soil characteristics that would help you make better decisions about your soils, or insight into what your ‘go-to’ dataset would be for your work.

• Sources of new datasets such as drone, or smart-agriculture telemetry, that you think should be collated into UKSO.

Direct feedback will not only help to continue developing UKSO as usercentred platform, but insights like this can help to support future research. It’s important we work collaboratively to ensure that soil health is given the attention it deserves in the climate change debate.

UKSO is funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), and Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC). For more information visit: http://www.ukso.org

-

Crimper Rollers

In 2017 the Rodale Institute talked about the use of crimper rollers in organic no-till. They said:

“In conventional systems, farmers can practice no-till by using chemical herbicides to kill cover crops before the next planting. Organic no-till, on the other hand, uses no synthetic inputs. Instead, small-scale organic no-till farmers use hand tools, like hoes and rakes. Largescale organic no-till farmers can utilize a special tractor implement called the roller crimper (below), invented here at Rodale Institute.”

How does a Crimper Roller work?

The roller crimper is generally a waterfilled (or solid) drum with chevronpatterned blades that attaches to the front of a tractor. More recently we have also seen them mounted on the front of drills as well. As the tractor drives over the cover crop, the roller crimper mows the plants down, cutting the stems every 16cm. The cover crop, now hopefully terminated, remains on the ground where it forms a thick mulch that suffocates weeds. Drills on the rear of the tractor then part the cover crop mulch, drill in seeds and cover them up to ensure soil contact. It generally happens in a single pass, saving vital time and energy for farmers. The cash crop then grows straight up through the cover crop mulch. But since we weren’t worrying much about glyphosate in 2017, the concept hasn’t gained much traction.

Timing is everything