If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Weed Suppression With Cover Crops: It’s All About Biomass

Written by Dr. Bob Hartzler and Meaghan Anderson of Iowa State University

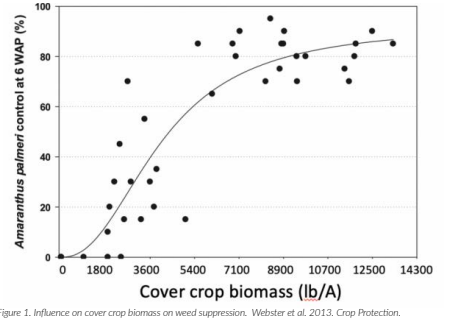

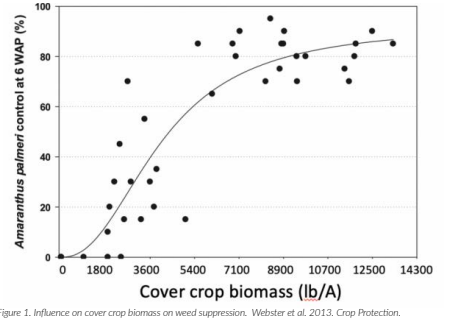

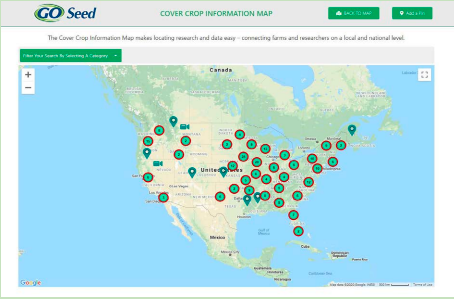

One important benefit of cover crops to our production system is providing an alternative selection pressure on weed populations. Cereal rye has the best potential to suppress weeds because it accumulates more biomass than other cover crop species. Weed suppression is closely related to the amount of biomass at the time of termination (Figure 1).

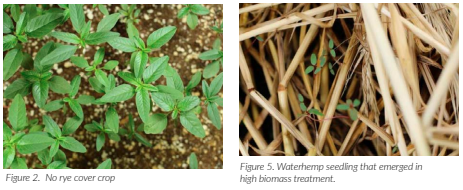

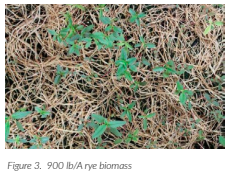

The importance of biomass on weed suppression can be easily observed in a demonstration evaluating suppression of waterhemp by cereal rye developed for the 2020 Farm Progress Show. Treatments represented no cover crop, an early termination when rye was 6-8 inches tall (900 lb/A), and late termination when rye was flowering (10,000 lb/A1). Three weeks after planting there were dramatic differences in both waterhemp emergence and growth (Figures 2-4).

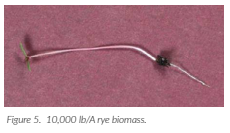

The low rye biomass treatment reduced waterhemp growth more than it did emergence, whereas the high biomass treatment dramatically reduced both emergence and growth. Waterhemp emergence was delayed more than two weeks in the high rye treatment compared to the 0 and 900 lb rye treatments. In the high residue treatment, \c seedlings had to navigate through an inch of mulch to reach full sunlight (Figure 5).

Hypotocotyl needed to elongate 1.25 inches to get through the rye mulch.

Many factors influence the biomass produced by cereal rye, most important are planting date and termination date. Rye’s tillering ability reduces the importance of seeding rate except in situations with late planting. A minimum seeding rate of 1-1.5 bu/ac is typically recommended. Increased seeding rates will provide more consistent stands when rye is seeding using an airplane or other broadcast methods, as well as when seeding occurs in October or later.

For most farms, cover crops provide an opportunity to achieve more consistent weed control and lower selection pressure for herbicide resistance, rather than allowing significant reductions in herbicide use. Farmers desiring to reduce herbicide use must manage the cover crop to maximize weed suppression. Target early seeding dates, typically before late September. Seeding with a drill typically results in the most consistent stand across crop fields. Termination timing should be delayed past mid-May to ensure rye biomass is maximized for the most persistent weed suppression.

110,000 lbs/A of rye biomass is higher than typically achieved in Iowa. The rye was drilled after harvesting corn for silage, and termination was delayed until mid-May.

-

Farmer Focus – Clive Bailye

If I was ever to write the script for a farming based horror movie I think the title may simply be “2020’’ ! Last time I wrote it was December 2019 and we were only 60% through our autumn drilling campaign. Well behind our usual planned October finish. The new 12m Horsch Avatar had been parked up and our farm workshop Co6 and front hopper tine drill was working in any available dry spell to complete the remaining workload. The Avatar coulter had been impressive in the unusually wet conditions, not blocking in conditions where I’m sure our 750a would have but ultimately its limiting factor was the weight of the seed cart on wet soils.

With a full 12/36m CTF system in place here any soil damage caused by weight on wet, fragile, soils is at least confined to a known and small % of the land which, if necessary, can be targeted to repair. However, repair means soil disturbance I would rather not do so the lightweight and balanced CO, able to run a low tyre pressures seemed the better choice in the extreme conditions. Also of note was the correlation between how long a field had been farmed under conservation agriculture principles and ability to drill, the longer term soils not only able to carry the weight of establishment machinery far better but far less prone to smear against the disc of the avatar or the tine of the C0.

Despite lacking the versatility of a disc when it comes to dealing with huge amounts of green cover and surface trash, on our soils a tine is better when soil is wet, and the less consolidated surface seems to give better establishment later in the season. Over the years of evolution of our tine drill we have experimented with various tine solutions. When first converted we used the Metcalfe points, I was attracted by their narrow profile of just 12mm and low price tag compared to others but quickly found on our stoney soils that the tungsten wear tile would often break off long before the point was worn out and that narrow profile led to very rapid seed tube wear and issues flowing larger seeds like peas and beans.

I set about creating my own modified version, initially this was just a wider version (15mm) using a Ferobibe wear tile that could be replaced with a farm workshop Mig welder. Unlike the tungsten, soil flow still created wear issues with the seed tubes so later protective side plates were added but I was never 100% happy with the design.

In 2019 I had the opportunity to try some Bourgault VOS openers, initially we fitted the twin row 100mm points, the quality was impressive and they worked well but 100mm was too much soil disturbance for my liking so we moved to the 19mm single shot point which seem absolutely perfect, low disturbance yet wide enough to flow even the largest of bean seed and with no seed tube to wear with it being internal to the point. I think this will be the solution we stick with going forward, they were pushed to the limits this year in conditions I hope to never see again, in combination with the Horsch Partner front hopper I think they were the only reason that on February the 15th we finally managed to complete 100% of the “autumn” wheat and bean establishment workload.

Having the right tools for the job and the right soil is only part of the picture, without the commitment, skills and tenacity of good staff no farming system can ever be successful, The herculean effort made by everyone here this season was exceptional, they worked at every available opportunity, safely and efficiently with their usual attention to detail. The sense of achievement by all, against the odds and conditions felt like sweet victory making the second part of this horror story even harder to swallow …

Despite the difficulties of autumn at least our OSR area all looked good, locally a lot of crops had been destroyed by CSFB not long after drilling, yet ours had all made it through winter and although not exceptional looked ‘alright’. As soil temperatures warmed and first nitrogen was applied though it became clear all was not good. Closer inspection revealed stems badly infested with CFSB larvae, there was no way the crop was going to yield, although hard to accept it was a write off and clearly best replaced with a spring crop of linseed creating a significant increase to our spring workload but at least with our low input, low risk approach to OSR the financial impact of losing the crop was minimised with just farm saved seed, a herbicide and 1/3rd of the nitrogen applied we can simply call it a cover crop and move on !

The future of OSR on this farm is doubtful, we seem to have got away without CSFB issues longer than some but it was inevitable it would hit us eventually, pests do not respect farm boundaries or hedgerows so regardless of IPM or soil health on individual farms there is nothing an individual farmer can do to remain immune to this problem.

Unlike many I believe the ban on neonicotinoids is not entirely responsible for this issue. In fact, I think this is a clear example of how unsustainable modern agriculture has become when an entire crop can seemingly no longer be grown. The blame in my opinion for this loss sits firmly at the feet of poor rotation, agronomy and often blatant, historic, disregard of IPM. Afterall I am certain the Romans who bought this crop to the UK farmed without seed dressings and pyrethroid. Yet in just one generation we seem to have made something possible for thousands of years, impossible. If that doesn’t make you question the overall direction of modern farming and its impact upon our environment, then it should, what crop will we be crossing off the options list next I wonder if we don’t change? Blackgrass problems anyone?

In mid-March the rain that had started on September 20th finally stopped rather ominously on Friday 13th of March. A total of 580mm had fallen through that time and only 8 days had no rainfall at all making it even more remarkable that we had somehow got that autumn workload complete. Soils started to dry, and we were soon able to get the spring crop establishment completed in good time and condition. Grateful to finally get some dryer condition to work in establishment was quick and simple compared to the trials and tribulations of the winter. We joked about a drought …….. and then it happened!

It was 82 days later, on June 3, when we had our next rainfall. At this point the wheat was almost dead. Tillers had been dropped and yield potential irreparably capped, spring crops had emerged and developed slowly, I think in some cases had we cultivated to establish them they maybe never have emerged at all. The farm really did not look great, the only consolation being a country in covid 19 lockdown at least I didn’t have to look at it very often!

I’m the first to criticise farmers for moaning, let’s face it, if you can’t deal with unfavourable weather then farming probably is not the best occupation to choose. I prefer to focus on things we can control as managers rather than things we can’t. I chose to accept this season as a challenge, if you can win a game of poker with a bad hand then surely you can still make a margin growing crops with bad weather?

The simplicity of the low fixed cost structure business I have set out to build suddenly felt more prudent that ever with a small payroll and machinery fleet to finance the next focus was on adjusting the variable costs to fit potential.

Fortunately we had applied 60% of the planned N to our wheat early, as the hot, dry conditions persisted it was fear of scorch and damage that led the decision to apply no more but ultimately as tillers aborted it was yield potential finally made the 60% into 100% of planned application. It was a similar story for other inputs, a cheap fungicide application made at T1 timing became all that was needed to keep wheat clean until the rain finally returned in mid-June. Spring crops needed just fertiliser and herbicides; I don’t think we have ever had a year where our usually very busy sprayer has been parked in the yard quite so much.

The result has been an extremely cheap year, ultimately a very simple year. Although we are unavoidably heading into a lower output harvest than we have seen here for many years I think this could be one of the best farm management years I have had, there is not a single decision I think I would change this year, not a single opportunity missed and I don’t think I have ever been able to say that before. I’m looking forward to harvest and remain hopeful that this farming horror story could just have a happy, ie. profitable, ending!

-

Manufacturers In Focus…

MANAGING STUBBLES WITH THE RAZORBACK RESIDUE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

Headed by Martin Lole, a farmer and engineer who has enjoyed a successful career as the driving force behind several leading UK vegetation and conservation agriculture brands, Razorback draws on over 100 years of combined industry knowledge shared by our experienced engineering, sales and service teams. Designed with superior quality, strength and versatility in mind, Razorback products undergo extensive testing during the development process to give operators piece of mind, knowing they have invested in tried and tested solutions. It’s on our own trial farm in Worcestershire that we developed a number of residue management systems including the Auto-Level hedgecutter with Co-Pilot technology as well as our latest development the RT Series rotary mower and RH Series trailed harrow.

Award Winning Slug & Weed Control

Launched earlier this year at LAMMA, the mower and harrow combination was developed to compliment direct drilling establishment by providing a reliable cultural control method for minimising weed and pest pressure. In recognition of this, the duo was awarded Gold at the LAMMA Innovation Awards in the Arable category and went on to win the LAMMA Founders Award for best overall innovation at the show. The judges commended the innovations ability to actively encourage a flush of weeds ahead of drilling and its potential for reducing reliance on molluscicides as a result of disrupting slug habitats. The mower and harrow combination work by consolidating two passes into a single operation, saving users time and diesel.

Stubbles are chopped and distributed evenly across the full working width whilst the trailed harrow shatters residue to significantly reduce slug habitats, providing a cultural control method and reducing chemical applications.

The trailed harrow features five rows of adjustable extra stiff 28” tines that offer high frequency vibration which enhance the shatter action to accelerate straw decomposition and stimulate weed chit. When following the RT Series rotary mower, stubbles can be topped, distributed and the surface stimulated to promote a flush of weeds and volunteers ahead of Autumn drilling in one pass.

By encouraging an even flush of weeds and volunteers’ growers can make better use of their available chemistry to achieve an effective weed kill.

Versatility and high spec as standard

In addition to its arable applications, the Razorback mower and harrow combination suits a wide variety of tasks including tidying up headlands and reinvigorating grassland by removing thatch from the lower levels of the sward.

Available in 5 and 7.5 metre widths both the mower and harrow are designed and built here in the UK. The RT Series rotary mower features double skin construction, full length replaceable skid shoes, and high specification Bondioli and Pavesi gearboxes and driveshafts. Unlike many rotary mowers, gearbox skirting protects the gearbox’s shaft seals and bearings from residue, string and wire which can cause unnecessary damage if left open to the elements. It is design elements like this that makes us proud to offer machines of a superior build quality that will stand the test of time.

For more information on any of the products in the Razorback range get in touch with our team on 01905 347347.

Scan the QR code to watch the Razorback system in action here:

-

Farmer Focus – David White

Thoughts and lessons learned from the season. Where to start???

Well the earth on the farm went from very wet over winter to very dry. April was the sunniest it’s been since 1929 I believe, with the drought being broken towards the end of the month by some very welcome rain. We have been treated to the clearest air and the bluest skies that anyone has seen for many decades. It’s a shame that it’s taken a global pandemic and shutdown of industrial operations and carefree travel to make the change to the environment that we have been aware is needed for a while now.

May continued dry and we start to think that we need some vapour trails and upper air pollution to create conditions for rain to happen again! Whilst we do all we can to improve soil heath and structure and increase SOM to improve drought resistance still on light land the effect of insufficient precipitation combined with high temperatures and high winds have drained yield potential. So thoughts turn to combating drought and coincidentally on the internet popped up an article The Drought Myth, An Absence of Water is Not the Problem by William Albrecht.

www.appropedia.org/Drought_Myth

which discusses the role of nutrition in combating drought. I have been adding trace elements to spray applications at every opportunity but have still found that the absence of water is a big problem. More work needed here. Even the more specialist bio extracts appears to have made no difference. Soil structure and subsoil is no doubt very important and I’m always reminded of this by the route of a pipeline which crossed a field well over twenty years ago. The crop is always stunted and looks hungry (see pic) but the same soil was replaced in the trench that was removed, just in a different order.

On the worst field I have for “hot spots” (see pic) the difference in crop changes dramatically in just a few inches. You would not think it was possible as we expect roots to roam for moisture and nutrition on top of their increased efficiency through association with Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Fungi. I will taking soil samples from 0-300mm and 300-600 analysed to see what differences can be found.

On top of how we physically farm the soil we are trying to reduce crop inputs, jump off the treadmill of nannying crops with insurance PPPs and let crops on our healthier soils with an increased number of beneficials stand up for themselves.

I have had success with this approach again this year with insecticide free crops of wheat and rape but less success with reducing fungicides. Learning where we can successfully cut back is still a work in progress. I refuse to be persuaded to apply a T0 to wheat preferring it to stand on its own feet but it’s surprising how quickly patches of yellow rust started to appear on my varieties of GP1 wheats. These being Zyatt, Solstice or Skyfall or a blend of the three. A T1 needed to be applied very swiftly, and to keep on top of the problem a well timed T2. Nothing saved there then!

Autumn insecticides are avoided when ever possible but we do need to be aware of the risks from the green bridge between crops, and on one field of wheat the aphid population that inhabited the volunteer oats and possibly were living in the excessive amount of wet chopped straw has infected the wheat fairly badly despite a poorly timed (with hindsight) insecticide application. As part of our IPM we really need to be able to get aphids tested to see what disease they are carrying and have regional data on this.

Spring seedbeds were a challenge following the excessive amount of winter rainfall but as a rule better (dryer) where the cover crops had been left growing until early February than sprayed off before Christmas, in this case to get a second flush of Blackgrass. The ground does need to be dry enough to crumble into the slot or at least not mush back together again after the seed is placed and in the early sprayed off field it was not. With hindsight again I should have moved this a couple of inches deep to let it dry but had no machine for the job other than going over it with the Horsch tine drill. To that end I’ve found and purchased a super cheap new 3mt disc and packer machine which I’m fitting a seeder box to. This will perform three tasks, 1. covercrop establishment, 2. light movement of any seedbed to dry it if necessary and 3. mechanical covercrop destruction to reduce reliance of, or number of lts/ha required, in producing a clean environment to drill into of glyphosate. This is something I trialed in late autumn 2018 with a very lovely but expensive Lemken Rubin machine with some success.

Headlands. I’m surely not the only one that has headlands that look better than the field! I haven’t quite worked out why this is but on a traditional cultivation system headlands were always the poor relation, especially in a wet year.

Thoughts around this are, better consolidation, in a no-till system is this possible? Fewer slugs due to consolidation. An effect of some type from the surrounding flora. Extra nitrogen due to me not cutting back the rate enough on the headland setting, but half of the N is applied as liquid! Drilling more slowly, or something else. Thoughts appreciated via Twitter or Farming Forum/BASE UK forum if you can please.

So to sum up. The farm doesn’t look too bad and with a well timed rain and a little less heat and wind in May it would have looked very good. I can’t blame the no-till system, now it it’s fifth year here, for any crops that look less than perfect other than some spring barley and that was down to poor judgement on the day by me. The better well bodied land has the better crops due to holding more moisture than the land with sand under it. The ability to chose either the disc or tine drill depending on circumstances has been invaluable with the JD750a doing a fabulous job in green catch crops and the Horsch Dutch conversion likewise into wet chopped straw on wheat after oats or second wheats. In fact the no-till system afforded me the ability to drill 130% of planned wheat area in what was one of the most difficult autumns we can remember.

Finally the desire to farm using many fewer artificial inputs is very laudable but there are risks when we back to rein back too far.

What is holding us back at the moment is the risk/reward balance, something organic farmers have much better sorted and to help progress Regenerative Agriculture more quickly premiums that support the way that we are farming would be helpful.

-

Field Lab: Organic Wheat Varieties Part 2 – The Results

Results and Discussions – Spring Assessments

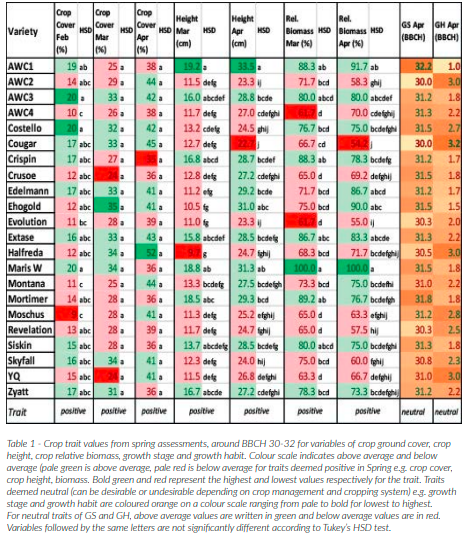

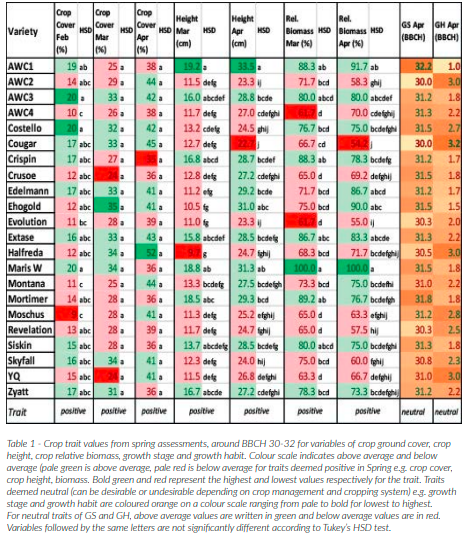

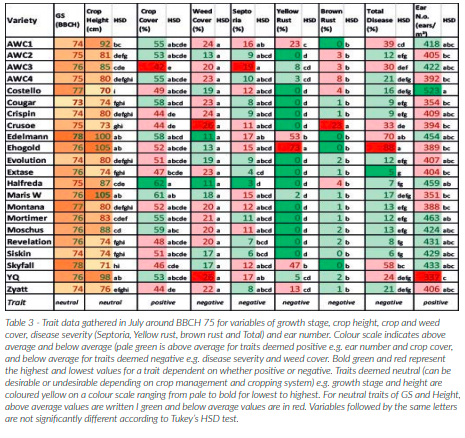

The above table shows different crop traits that can be easily measured around stem extension, a key growth stage signalling the end of the Foundation Phase and the start of the Construction Phase. Several of the traits relate to crop vigour in the spring, which is desirable for organic farming, offering greater competition from the crop against weeds and for resource capture.

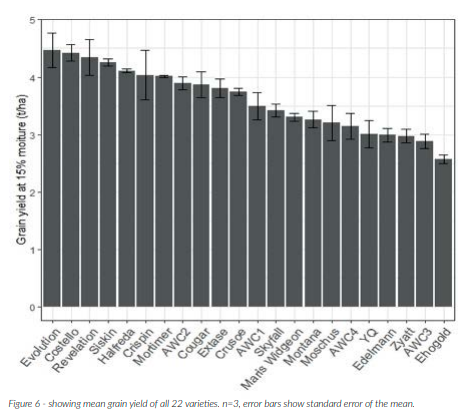

Extase and AWC3 showed consistently above average positive spring traits, whilst Evolution performed consistently below average across these traits. Many other traits contribute to yield and quality and it should be noted that despite it’s apparent deficiency in terms of spring vigour, Evolution was the highest yielding variety in the plot trial.

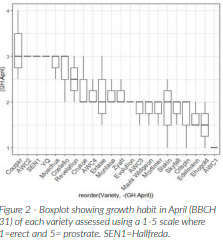

Growth Habit

A relatively simple assessment to perform, varieties can be classed according to five growth habit groups from 1 (erect) to 5 (prostrate). This trait may have implications for the crop management as shown below in the farmer rankings with different weeding strategies dependent on certain growth habits e.g. erect types may be better for inter row hoeing. The trait may also provide an indication of competitiveness, with erect types generally taller and the prostrate types generally providing greater groundcover. Which of these traits may be most useful will depend on a number of factors including the farm (soil, weed community etc.) and the year.

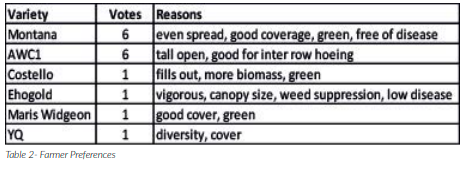

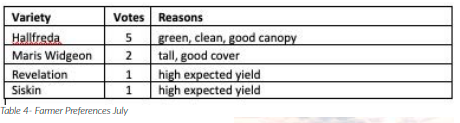

At a field lab meeting in April, farmers were given the opportunity to vote for their favourite variety based on the phenotypes in front of them. Most of the farmers expressed a preference for varieties with high biomass and good groundcover. Montana and AWC1 (Mv Fredericia) were voted the best varieties though for different traits. Montana was selected for its good ground cover, greenness, even spread and moderate height while AWC1 was selected for being tall and open making it suitable for inter row hoeing. This result illustrates the difficulty in selecting a one size fits all variety or so called ideotype for organic farming. The farm and crop management will heavily influence which variety is best suited for that system.

Late flowering/Early milk Assessments in July

Key traits measured in July around late flowering/early milk give an indication of varieties with mostly positive attributes for example disease resistance for the three main foliar diseases, good crop cover and high ear numbers. While ear density is usually the most important of the three yield components, it is not strongly linked with yield here, with grain number per ear and individual grain weight (size) also important. Some varieties with a large number of ears also had rather small ears (i.e. lower grain numbers per ear) and smaller grain. Crop height is generally regarded as an important trait in organic production with taller crops usually deemed desirable for their additional weed smothering and competitiveness.

Of course, crop canopy and cover are also important and height in and of itself may not always be beneficial if the canopy is also very open allowing weeds to compete. For this reason, final height has been treated as a neutral trait particularly given farmers comments about lodging and certain mechanical weeding practices (e.g. weed surfing) that may put taller crops at a disadvantage, or at least make them less desirable. On highly fertile ground taller crops may lodge with associated reductions in yield and grain quality possible. However, in certain circumstances where there is a large and competitive weed community, taller crops can be the difference between satisfactory and very poor yields.

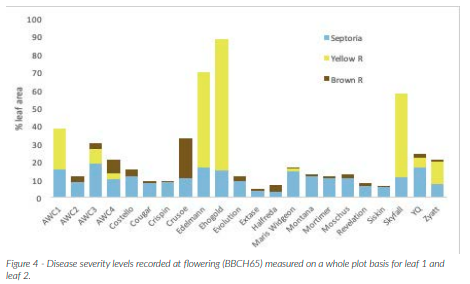

Disease

The chart above shows the mean disease severity for the three most important foliar diseases. While disease is often considered by organic arable farmers to be of less importance than either nitrogen and/or weeds in terms of yield limiting, all things being equal, varieties with higher disease resistance will always be desirable. Increased nitrogen availability in conventional trials limits the relevance of so called “untreated” data as there is a known link between nitrogen and disease susceptibility, particularly for Septoria (Loyce et al 2008). Having said that, untreated yields and the relative yield compared to control varieties, used by the RL can be a useful indicator of overall disease tolerance or resistance, with those untreated varieties showing the lowest relative yield reduction compared to treated controls likely to be suitable for organic production. In fact, the best performing varieties in terms of yield also tended to show the lowest mean disease severity e.g. Crispin, Siskin, Evolution, Revelation, Hallfreda.

Varieties with high relative untreated yields on the Recommended List will have high disease resistance and are likely to be highly desirable for organic farming though this data comes from the testing regime for the RL with full fertiliser and herbicide inputs, offering only limited relevance to organic farmers. What is clear is that having a high relative untreated yield is not enough for varieties since they must have a high relative treated yield in order to be considered for the RL.

This means that varieties that show a promising relative untreated yield, and therefore potential suitability for organic farming, can be rejected on the basis that yields are not high enough compared to control varieties under treated (with fungicide), high input conditions. This is clearly an issue for the organic sector with the variety Mortimer offering evidence of this bias. Mortimer has performed consistently well in the organic plot trials for the last two years showing good disease resistance and high yields and has shown promise in terms of its untreated relative yields in NL trials. However, due to its below target treated relative yields the variety has fallen from commercial production despite it’s high disease resistance scores and potential for organic farming.

An argument could be made for a small additional RL that only required high relative untreated yields for varieties to qualify as this would keep additional disease tolerant varieties in circulation and would increase the amount of relevant data for Organic farmers and for those farmers looking to decrease chemical inputs. At present, very disease resistant varieties can easily fall away without showing high fungicide treated yields and the RL is therefore facilitating this loss of naturally disease resistant material. This idea could be taken a stage further to include untreated in terms of nitrogen fertiliser to provide relative yields that would give an indication of those varieties better able to access soil nitrogen.

The 2018/19 season was a challenging one for yellow rust with the two varieties Ehogold and Edelmann were found to be particularly susceptible (Table 3). Severe yellow rust on these two varieties badly affected grain fill and led to a poor yield performance. Both these varieties are organically bred and were included to compare their performance against conventionally bred material given that organically bred materially may show greater adaptation to organic cultivation, given its selection under organic conditions.

However, these varieties were imported from Austria and show that continental varieties can be susceptible to UK races of rust and these varieties must be well tested to confirm resistance in the target production environment before bringing into commercial production in the UK. That said, the conditions were perfect for yellow rust with a mild winter, followed by a warm spring and overnight dews leading to an epidemic. During 2019 higher than expected levels of yellow and brown rust were seen in some varieties. It is not yet clear if the reported cases of high yellow and brown rust disease levels in 2019 indicate the initial emergence of new rust races or exceptionally high disease pressure at some sites due to optimal environmental conditions.

Voting for preferred varieties at a trial meeting in July allowed farmers the opportunity to pick varieties based on a different set of traits and selection criteria than at the meeting in April. Varieties showing good canopy cover, a high green leaf area, low disease levels and a high expected yield (based on ear number and size) were most desirable. Hallfreda, the near market line from Sweden was the winner, mostly thanks to it’s very green and clean appearance and good canopy cover due to its high levels of disease resistance and later maturity.

Yield and Quality data

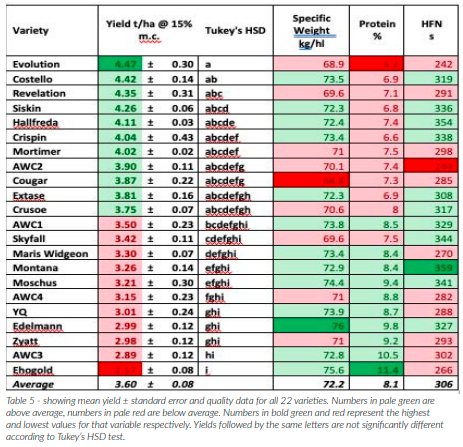

The average yield of the plot trial in 2018/19 was 3.60±0.08 t/ha. Whilst Tukey’s HSD scores show very few varieties are significantly different from each other in terms of yield (see Table 5), the varieties do tend to fall into a below average yielding generally higher quality group (particularly with respect to protein) and an above average yielding generally lower quality group otherwise summarised as a genetic yield (Y) and quality (Q) cluster. Yield and Protein show the typical inverse relationship.

The two groups are generally considered as wheats for milling (Q) and wheats for feed (Y). Looking at Table 5 can help show varieties that may buck the trend such as AWC1 (Mv Fredericia) that comes top of the below average yielding Q group whilst showing high quality for all three variables measured. Hagberg Falling Number (HFN) is a standard measurement for milling quality but is highly linked to crop phenology and ripening making it an awkward variable to include given that the logistics of a plot trial mean all varieties must be harvested together.

This means, that earlier ripening varieties will have a bias against them as they will likely come to maturity several days before the trial is harvested. While still useful as an indicator of quality, this fact should be considered when comparing HFN data. Ehogold illustrates this point well as the earliest ripening of the varieties tested and with high bread making quality attributes, it had one of the lowest HFN numbers.

Investigation of Traits

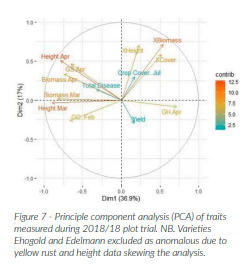

Figure 7 shows the principle components that explain the most variation in the dataset from the 20 varieties (excluding Ehogold and Edelmanm) and the 3 replicates assessed (60 plots) based on all measured traits. These principle components correlate with certain traits which are plotted on the figure and the strength of the correlation indicated by the colour (contrib: red = high and blue = low).

Of all the traits measured the height in March and April, and the relative biomass and the change in relative biomass (the difference between biomass in March and April: XBiomass) are the variables most strongly correlated with PC1. These may be considered a measure of spring vigour. Height in March and biomass in March also strongly influence PC1 while growth habit in April (GH April) also influences PC1. PC2 most strongly correlates with the change in biomass (XBiomass) and the change in height (XHeight). Variables in blue (i.e. yield, crop cover in July and Total disease) have a weaker influence on the principle components. Note that some variables have been excluded entirely from the PCA given their very weak influence on principle components.

We can also look at how the different traits correlate with one another, by looking at the angles between the trait vectors. The smaller the angle the more positively correlated while the larger the angle the more negatively correlated.

Trait vectors at 90 degrees are unlikely to be correlated. Observing the above PCA shows that yield doesn’t appear to be strongly correlated with any traits. The only trait that comes close is the growth habit measured in April with a small suggestion that more prostrate growth habit may be linked with a higher yield, but this is a very weak correlation and can essentially be disregarded. Yield is negatively correlated with total disease, growth stage in April (GS.April) i.e. more forward varieties, and height in April (which will in part be influenced by phenology, since the earlier varieties will be further through stem extension and hence taller). The varieties with more biomass in April also appear to be negatively correlated with yield.

2017/18 and 2018/19 Variety Yield

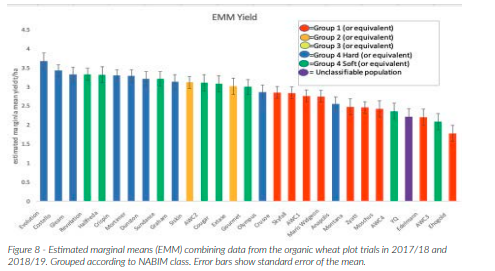

Estimated marginal means correct for bias due to differences between year to provide a more accurate aggregated mean yield for each variety to enable comparison of varieties averaged across years when certain varieties appeared in only one of the years. The 2017/18 trial yielded a grand average of 2.3t/ ha compared to the grand average of 2018/19 of 3.6t/ha. This represents a yield in 2017/18 of 64% the yield of 2018/19.

This approach has been useful in identifying varieties potentially unsuitable and hence worth dropping from the variety trial. For example, Anapolis as a group 4 falls outside the clustering of the rest of the group 4s that are higher yielding, and falls within the lower yielding, higher quality cluster of the group 1s. Similarly, new group 1 equivalent milling varieties like Ehogold and Edelman don’t appear to offer more productivity than the current collection of group 1 varieties including Crusoe and Skyfall. AWC1 (Mv Fredericia) does look to have potential for organic production after two years with good productivity and excellent quality. The varieties Mortimer and Hallfreda as hard and soft group 4 equivalents respectively also look to have good potential for organic production on a commercial scale, showing good productivity within the cluster of high yielding group 4 types.

Individual site findings; The Farm field scale trials

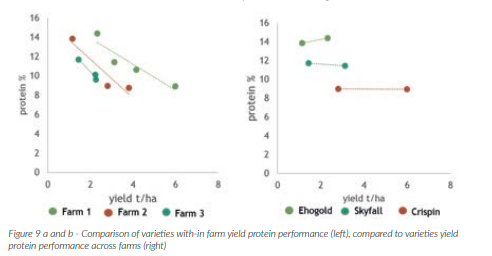

The three farms that each grew a selection of three to four varieties for comparison at a field scale, did so utilising farm management practices to give a more reliable estimate of commercial performance. This was linked with a wider varietal testing network supported by the LIVESEED project. When looking at the varieties grown in each individual farm, these tended to align along a yieldprotein trade-off. However, observing any individual variety across farms, there is an evident change in yield with a reasonably constant protein content.

Thus, the yield protein trade-off, generally seen as a big limitation especially for organic production, does appear across varieties within an individual farm, but not necessarily within a variety across farms (Graph 9 b). These trends are being analysed across the wider Liveseed farm network, hoping to shed light on optimal environments and management systems to help maximise wheat yield and quality. These results could help organic farmers plan their target market and hence varietal selection more effectively to meet market specifications, with some of the highest yielding farms in the wider farm network able to achieve >12% protein content, a particular challenge for organic winter wheat production.

-

AHDB Strategic Cereal Farm Week

Sharing AHDB’s Strategic Farm demonstrations and practical ‘how to’ resources virtually

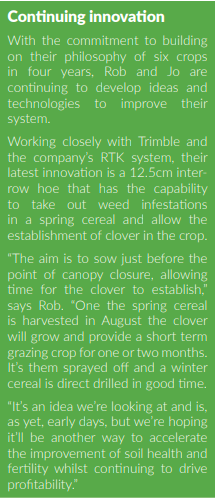

AHDB’s Strategic Farm Week goes digital

Usually, summer sees each AHDB Strategic Cereal Farm host open their doors to those interested in learning about the research programmes put into field scale demonstrations onfarm. However, due to Government restrictions, this year’s programme took place in a purely digital format comprising videos, webinars and a podcast. The webinars during the week covered a range of topics including monitoring crop development, pests and diseases, reducing chemical inputs and masterclasses on crop establishment, soil structure assessments, mole drainage and soil loosening. Experts from AHDB and across the industry led the sessions including pioneering farmers Simon Cowell and Tim Parton, and soil expert Philip Wright.

This year, Strategic Farm East host, Brian Barker from Lodge Farm, Suffolk and Strategic Farm West host Rob Fox at Squab Hall, Warwickshire, were joined by a third. Farm manager David Aglen, is the newcomer having joined the Strategic Cereal Farm programme earlier this year, extending the network up to Scotland for the first time. Having yet to start trials at Balbirnie Home Farms, David is interested in looking at regenerative agricultural practices, plant and soil health and carbon offsetting through the Strategic Farm Scotland programme. David said: “There is little research going on into regenerative agriculture in the UK currently. This is the direction we want to take our business so working with AHDB offers the opportunity to harness the research available and get more work done to help us and the industry succeed in moving towards our goal.”

At Brian Barker’s farm, a lowering inputs demonstration is one of several demonstrations taking place, which was showcased during the week alongside research looking at cover crops, perennial flower strips and boosting early crop biomass. Lower input, higher margin farming, regenerative farming and soil management all came together in one of the key webinars of the week in which Brian Barker, Tim Parton and Simon Cowell took part, see the featured article. Farm manager, Rob Fox is overseeing a separate set of demonstrations in the west of the country looking at soil cultivations, the impact of summer catch crops and pests and natural enemies.

This season has been a particular struggle for Rob, who at one point was considering throwing in the towel altogether. Following a season of heavy rainfall, he struggled to get crops in the ground, let alone establish his demonstrations. As a result, a significant portion of the research programme at his farm had to be written off.

Since then Rob has soldiered on having endured, along with the rest of the country, a prolonged dry spell; going from one extreme to the other. “It’s been a tough growing year meaning we’ve had to reduce what we had planned for the season. “It’s not all been bad news though as we’ve been able to add in an additional demonstration looking at summer catch crops. We’ve planted two different mixes: one is a bought-in mix of phacelia and fodder raddish, the other is home saved spring beans and spring barley. The aim is to see if they is any benefit to the following wheat crop.” Attention now turns to later in the year, as the summer approaches and harvest 2020 beckons. AHDB looks forward to your joining us to hear about the results from all the harvest 2020 demonstrations at Lodge Farm and Squab Hall in the autumn.

To access any of the content from Strategic Farm Week 2020, including watching back the webinar videos, please visit: https://ahdb.org.uk/sfweek2020 To find out more about the host farms please visit the dedicated webpages using the links below:

• Strategic Cereal Farm East (Lodge Farm): https://ahdb.org.uk/farmexcellence/strategic_cereal_farm_ east

• Strategic Cereal Farm West (Squab Hall Farm): https://ahdb.org.uk/ farm-excellence/strategic_cereal_ farm_west

• Strategic Cereal Farm Scotland (Balbirnie Home Farms): https:// ahdb.org.uk/farm-excellence/ strategic_cereal_farm_scotland

How to decide when to lower inputs

AHDB’s Knowledge Exchange Manager for Scotland, Chris Leslie, hosted the “How to decide when to lower inputs” webinar, as part of Strategic Farm Week in June 2020. Here he talks through some of the key findings and topics of conversation from the webinar, featuring farmers Simon Cowell, Tim Parton, Brian Barker and David Aglen, along with Catherine Harries, AHDB.

Changing systems, changing mindset and learning to work with nature were key themes throughout this webinar exploring the topic of lowering inputs. This topic is one that is being looked at across the three AHDB Strategic Farms through their demonstrations and six year programme. All of the farms are at differing points on the road to regenerative agriculture, the system of farming principles and practices that increases biodiversity, enriches soils, improves water quality, captures carbon and enhances ecosystem services.

Agriculture is disruptive by its very nature. However, our three Strategic Farmers as well as Tim and Simon, aim to work alongside nature and put soil and the environment at the forefront of their farming system using tools such as IPM and no-till. Tim Parton stated right at the beginning of his presentation, that “I find when you work with nature, rather than fight nature, it works”. A key part of moving towards this system is to find ways to farm with less inputs. For Simon Cowell, this has included a range of options that have been put into place on his heavy clay farm in Essex, such as: stopping growing oilseed rape, the introduction of perennial crops such as lucerme and aiming to overlay crops through the rotation to support soil biology and mycorrhizae.

This change of the rotation has enabled Simon to halve the nitrogen used on farm, from when he was in the previous system of growing solely wheat and oilseed rape. Simon admits that “it’s difficult to back off and say I’m not going to spray any fungicide or put on any phosphate fertiliser” and understands that every farm is set-up differently, with some paying high rents and mortgages. However, the importance of getting your soil in the right condition before you start to reduce inputs was a key part of the solution. For Simon, he has been able to speed up this process by using home-made compost to enable the biology to function and for the nutrients to the circulate and more.

Simon noted that his preference is to not focus on the margins of individual crops instead, ”it’s about the whole rotation that we’re considering, its better to not think about each one individually. It’s a longer term thinking all together ”, he says. Brian Barker also discussed how he is looking at how far he can reduce inputs in his crops at the Strategic Farm East. As one example, a demonstration taking place this year on-farm is looking at reducing plant protection products and fertiliser to see what impact this will have on pest and disease pressure, crop yield and net margin. The farm has applied a reduced input programme in a field of winter wheat and will compare the results with a conventionally managed crop at harvest.

The work is part of Brian’s ongoing interest in looking at how far it is practically possible for farmers to reduce inputs. Last year he tested the natural resistance of winter wheat varieties by applying three different fungicide application programmes to see which gave the best margin. “This is all about changing mindsets as we’re going to have to look at alternative ways of protecting our crops. In this demonstration field, we ploughed it due to previous blackgrass populations, planted naked KWS Siskin seed, applied a pre-emergent herbicide, no insecticide, one PGR at T1 and only spent £14/ha on fungicides at T1 and tebuconazole at T3 due to rust coming in late.” said Brian.

“Weaning myself off using inputs hasn’t been easy and it’ll be interesting to see how this crop does. Last year the yields held up quite well; the wheat that received the lower input programme produced the best cost of production by a long way and yield held surprisingly well. Lack of moisture is clearly going to be significant this season which was similar to last year.”

For farmers starting on the journey, this thinking, following the Strategic Farm work and asking the questions of research, along with building soils might be a good place to start.

Given the extremes of the last two seasons, some farmers have looked into going back to cultivations when transitioning to a regenerative agriculture system – something that was eluded to several times during the course of the webinar by both Tim Parton and Simon Cowell. Managing these extreme weather patterns is often the difficult part when in transition, as you learn to work with or understand the natural systems. It is acknowledged that it is incredibly hard work and often years of change to take soil from a conventional system before getting to a place where the soil starts to work for you rather than against.

No one piece of machinery holds the key, with all involved in the discussions having different types of machinery on their farms. It has more been the use of synthetic inputs and often a lack of organic nutrition, which has created the current reliance on inputs. We need to start to examine how we look after our soils, so that our crops can remain green for longer when the next dry period appears. It is by doing this that inevitably allows us to reduce our artificial inputs. This webinar was just a start of the discussion and the conversations and research will undoubtedly continue.

To watch the webinar session back, please visit the AHDB Cereals and Oilseeds YouTube channel or link through from: ahdb.org.uk/sfweek2020.

For all of the details about the demonstrations taking place at the Strategic Farms this year and the results to-date, please visit the webpages at: https://ahdb.org.uk/farm-excellence.

-

Cover Crops On Trial

AHDB’s Technical Knowledge Exchange Manager, Harry Henderson, takes a look at the results from the recently published Maxi Cover Crop research findings and discusses what lessons you can take-away for your farm system.

Cover crops. You’ve read the articles of untold benefits of soil restructuring, drainage improving nutrient building, weed suppressing, disease controlling, yield enhancing, resilience building, environment saving, superhero cover crops. You’ve seen the videos online of drills working in bonnet high cover crops without issue and crimper rolls seemingly doing away with agro-chemical control. It must be a no-brainer to get involved in cover crops.

But on the 11th May this year the AHDB issued a press release and a 111 page report of a 3-year cover crop trial with the standout comment being; Cover crops were associated with an average gross margin loss of £150/ha across two consecutive arable cash crops. How could this be? I phoned a couple of my colleagues and they said ‘It is the experience of many farmers starting out using cover crops’. Clearly, a further look into the report is necessary and this publication is the place to do it. Does the report have gaps? Sure. Does the report highlight real findings and put some realism into what is an ever-evolving story? Definitely.

So, the AHDB funded a three-year “Maxi Cover Crop” project, which aimed to maximise the potential agronomic, economic and ecological benefits from cover crops through investigating different cover crop options and crop management approaches.

In a recent survey of UK farmers, the most cited reasons for not growing cover crops were:

1. They did not fit with the current rotation

2. Expense

3. Difficulty of measuring their benefit to crop production.

The Maxi Cover Crop project has shown that:

• Early establishment (August rather than September) is important to maximise the benefits of cover crops, particularly to ensure good crop cover and nutrient recovery. Typically, the different cover crops yielded between 1 and 3 t/ha above ground biomass and took up between 30 and 50kg N/ha, although up to 90 kg/ha N was recovered following early establishment at one of the sites.

• Highest N recovery was achieved by using either species that were able to fix N from the atmosphere (i.e. clover and vetch) or establish good above or below ground biomass, early in the season (e.g. radish, phacelia and rye).

• Rye produced the largest root length early in the season. Phacelia also rooted well although the roots were slower to develop. By the time the cover crops were destroyed (February), phacelia had produced the greatest amount of roots, particularly in the topsoil, and it also had the narrowest roots, suggesting it explored more of the soil for a given root biomass compared to the other cover crop treatments. There was no relationship observed between the amount of cover crop rooting and rooting of the following spring cash crop.

• Soil structural improvement from a single year of cover cropping was difficult to detect. However, at two of the tramline trial sites with medium textured soils, penetration resistance, bulk density and visual structural scores were lower (i.e. ‘better’) where cover crops had been grown indicating improved soil structure and workability. Earthworm numbers were also increased where a five species mix (comprising phacelia, oats, oil radish, clover and buckwheat) had been grown.

• Cover cropping on heavy textured soils was shown that it can result in increased topsoil moisture content, probably as a result of the vegetative cover preventing evaporation from the soil surface.

• Late destruction and incorporation of a high cover crop biomass (< 1 week prior to drilling) resulted in poor seedbed conditions for the establishment of the following cash crop, which led to lower crop yields.

• Cereal cover crops (as a single species) should not be grown ahead of a spring cereal cash crop. At the experimental sites, spring barley establishment, rooting to depth and grain yields were all reduced following oat and rye cover crops. The reason for this is uncertain, but N immobilisation, and pest and pathogen carry-over (‘green bridge’) have been cited as possible causes.

• A buckwheat cover crop may enhance P availability to the subsequent cash crop. At the experimental sites, there was a trend for higher phosphorus concentrations in spring barley grain following a buckwheat cover crop compared to the control (volunteer/weeds). It is uncertain what the mechanism is for this, as rooting by the buckwheat and total above ground biomass production was low compared to the other species evaluated.

• A single year of cover cropping does not improve gross margins. Nearly all the cumulative (2 year) margins calculated across the sites (20 comparisons) showed a reduction in margin from growing a cover crop compared to no cover crop (ranging from + £64/ ha following oil radish on a clay loam to – £476/ha following a two species mix on a clay soil). The lower margins were caused by an absence of sufficient yield increases to compensate for the additional seed and establishment costs. The benefits from changes in soil physical properties or nutrient dynamics are unlikely to appear within the 2 years of the project so the longer-term use of cover crops over a full rotation (including more than one year of cover cropping) is required to fully assess the impact on margins. Moreover, non-tangible benefits such as improved water quality, erosion control and enhanced biodiversity should be considered as a wider public good.

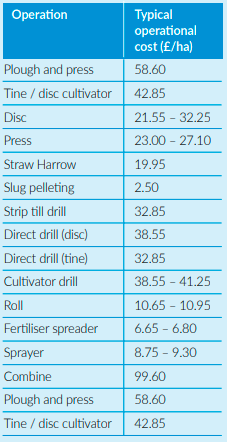

Tackling that headline statement of £150/ha loss. The operation costs, while representative, are at the top end of where costs tend to be.

The Monitor Farm average for combining is £66/ha for example. And disc based direct drilling varies from £19 to £30/ha depending on how much land you cover with it. S,o operation costs used in the trial are 30% more than you’d hope to face.

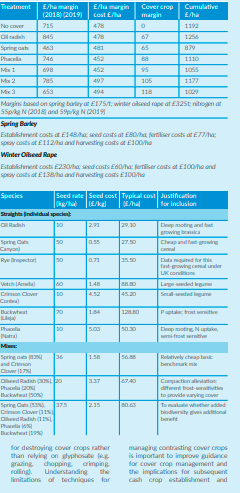

As an illustration, at the Kneesall, Nott’s trial site, the spring oats had the lowest cumulative margin of £879/ha due to a yield reduction of 1.43 t/ha compared to control, (stubble and cereal re-growth) which may reflect the rotational conflict of growing a cereal after a cereal cover crop. The highest cumulative margin was from the oil radish which was £1256/ha, which reflected the higher spring barley yield and low seed costs compared to the other treatments. The control cumulative margin was £1192/ha. The cost of establishment of the cover crop ranged from £65/ ha (spring oats) to £118/ha (mix 3 – spring oats, crimson clover, oilseed radish, phacelia and buckwheat). It’s perhaps unfair to expect a cover crop to return on investment from yield improvement alone. Especially in year one. As we have realised at many a Monitor Farm meeting, building soil resilience is a career long objective and adopting cover crops should enable lower machine costs, much lower than used in the trials. Cover crops should also extend working windows and improve surface drainage, but again these are long term aspirations rather than quick fixes.

With all field trial work, while questions are answered, more questions are raised. That well-worn phrase ‘more research is needed’ certainly stands true in this case. And arguably a greater look into adopting cover crops into a system of changes on the farm, to lower cost, reduce reliance on inorganic solutions and improving overall farm resilience is needed.

Future research suggestions included:

• Understanding the fate of N recovered by cover crops – when this N is released and how much is released. The ability to predict mineralisation rates for different cover crop species grown on contrasting soil types in different agro climatic zones will improve fertiliser recommendations for subsequent cash crops.

• Evaluating alternative methods for destroying cover crops rather than relying on glyphosate (e.g. grazing, chopping, crimping, rolling). Understanding the limitations of techniques for managing contrasting cover crops is important to improve guidance for cover crop management and the implications for subsequent cash crop establishment and effects on soil properties and N supply.

• Evaluating the long-term (multiple cycles of cover cropping) benefits of cover crops. What are the benefits for soil organic matter, soil biology and associated soil properties.

• Quantifying the economics of growing cover crops and the potential income from livestock grazing or the reduction in inorganic nitrogen fertiliser application in the following cash crop.

• This study showed that rye and to lesser extent spring oats resulted in slower development of spring barley early in the season and lower yields at harvest. Further work is required to understand the cause of the cash crop yield reductions (e.g. nutrient availability, disease pressure, etc) and whether cover crop mixes can be developed that do not lead to reduced yields. This has implications for EFA’s which require cover crop mixes to include a cereal and non-cereal. • In this study, there was some evidence suggesting that buckwheat may enhance P availability to the following cash crop. However, further work is needed to understand the mechanism for this, and given the cost of buckwheat, how much of a cover crop mix needs to be buckwheat for this benefit to be achieved.

While there’s lots still to understand, it is a no-brainer that covered soil is good for farming, the environment and will pay dividends in the long term. So a longer term look into cover crops would the best as the next steps for research. All three AHDB Strategic Farms in Warwickshire, Suffolk and Fife, Scotland will address cover crops over their 6-year programme and incorporate them into each farms long term thinking. Make sure you check in either online with the results from these farms as they come through, or in due course, in person.

For further information on cover crops and to download the project report, scan the QR code below:

For further information on the Strategic Farms, visit: scan the QR code below:

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

NEW FLEXIBLE SEEDING OPTIONS FROM KUHN

Supplementary seeder range adds versatility

KUHN has introduced a range of supplementary seeders that can be fitted to its Venta, Espro and Aurock pneumatic drills to facilitate progressive practices such as companion cropping or apply fertilisers, granular herbicides or slug pellets whilst drilling. The smallest model in the SH seeder range is the SH 1120, with a 110 litre hopper. In this case, air from the drill’s main fan is used to direct product into the venturi to enable it to be applied with seed from the main tank. The larger SH 1540, SH 2560 and SH 4080 models, with 150, 250 and 400 litre hopper capacities respectively, are equipped with their own electrically driven fans and apply product via splash plates behind the main seeding lines. All models use KUHN’s Helica volumetric seed metering system, as used successfully on their range of mechanical drills, to maximise the accuracy of output. Application rates are controlled through the ISOBUS system in relation to the forward speed of the tractor.

“The SH seeders are an effective way of adding great versatility to KUHN pneumatic drills,” says KUHN UK Product Specialist Ed Worts. “With the main drill sowing seed in the usual way, the SH seeder can be used to sow a secondary seed, such as a companion crop used to suppress weeds, add soil fertility or act as a pest deterrent, for example. “The SH seeder can also be used to apply starter fertiliser, slug pellets or a granular herbicide such as Avadex, such is its versatility and adaptability. “In the case of the Espro RC and Aurock RC, which have split hoppers as standard, the SH seeder adds a third application possibility. This allows a variety of applications to suit individual requirements and reduces the need for expensive seed mixtures.” On the larger SH 1540, SH 2560 and SH 4080 models, application rates between 2.2kg/ha and 130kg/ha can be accurately achieved alongside the application from the main drill.

Adaptable seeder offers cost effective establishment option

A cover crop seeding unit, compatible with a wide range of minimum tillage cultivators and capable of applying all types of seed, or fertiliser, at rates from 1 to 430kg/ha, is available from KUHN Farm Machinery. The SH 600, equipped with KUHN’s Venta metering unit and with the option of 16, 20 or 24 outlets from the distribution head, is designed for uniform seed spread across a 3–9 metre working width. Seed is distributed via discharge plates located in front of the cultivator roller to achieve optimum soil-to-seed contact. Precise and simple application rate settings are achieved using KUHN’s Quantron S2 control terminal, which aligns output with forward speed. Quantron S2 also monitors seed level and controls fan speed and metering unit speed. With a 600 litre hopper, the SH 600 has big bag capacity, and the machine is fitted with a ladder and walkway to allow safe and easy access when filling. The SH 600 is specifically designed to operate with KUHN’s Prolander, Performer, Optimer XL and Cultimer L 1000 minimum tillage and stubble cultivators and is sufficiently adaptable to work with other makes of machine.

-

Farmer Focus – Adam Driver

What a season we have had! Its years like this when we can really learn a lot about our farming system and what we are trying to do.

So, it went stupidly wet stupidly quickly. We have had some really easy seasons in the past 5 years where we have been able to drill later for blackgrass control. Can we start drilling earlier again with low disturbance drills now we are on top of the problem? I hope so. Should we be growing catch crops in front of winter crops? I think this can really help mitigate some of the issues with heavy rain, catch crops will pump water in the autumn. It is often claimed they do this in the spring however from personal experience this is not true. For the autumn I think it is far more plausible as the plants are generally growing pretty fast.

Soil structure, of course is at the forefront. Better soils infiltrate more water and hold machinery (even big heavy stuff) far better than fluffy cultivated stuff. Good soil structure is at the core of what we are all trying to do and a season like this highlights that even more. There were many horror pictures of soils washing away due to poor soil management on social media. It gets dismissed as the “weathers fault”. Not a good enough excuse for me I’m afraid. Seeing these kinds of pictures and the excuses that went with them were frankly worrying and highlighted the lack of ownership UK farmers have of their problems.

Drainage is something that has come up again with a season like this. With no tilling on hanslope clay soils I think good drainage can be the difference between success and failure. We do a lot of mole draining, often in the spring and the better drained fields look so much better for it in both winter and spring crops. Some of the old drainage systems are starting to really show their age now so we will be looking at ways to either repair or replace them. I have an appointment to view a tractor mounted trencher next week. Afterall, there is loads of free time when you aren’t making dust with cultivators for months on end!

The spring as we all know, was equally ridiculous. There is no way a soil should go from being absolutely sodden to being too dry to germinate a crop in 5 days as some were reporting. Soils just aren’t working properly in many places around the country, including some of my own. These extremes of weather do appear to be becoming more regular. We need more resilient soils in order to deal with them. I discussed with a friend the other day about the regen journey we are both on. He pointed out as farmers we are so used to be able to instantly buy a piece of kit, a chemical or a fertiliser that gets us out of muddle or solves a problem, or it has in the past. What we are doing now is a much longer game. We need to focus on the core principles and not revert in panic if something goes wrong. Over time as we build our soils, gain a better understanding of the soil biology and the intricate ecology we are working with and share knowledge. Our soils will improve and shelter us from these extremes of weather and volatility of the industry.

What is the solution to all this? Keep learning, keep pushing, keep trying. There are no magic bullets!

A quick update on crops. OSR, this looks okay and will be ready for harvest in about 7-10 days (its 28th June today). I don’t expect it to break any records but has been grown very cheaply, it should offer a reasonable margin with minimal capital risked. Wheat looks average to poor. Spring crops are a mixed bag but generally pretty good. Winter barley looks well and will be harvest next week. I am looking forward to getting this years crop out the way, chasing the combine with the muck spreaders and drill planting OSR and cover crops.

UK agriculture is at somewhat of a cross roads. A red blue pill, blue pill moment. Whilst it used to be “conventional vs organic”, the regenerative group has formed. I have started to try and view the way we farm as treating causes not symptoms, conventional farming has always been about treating symptoms. This has worked well for a long time and done its job. However, we are on a treadmill in which we externalize all of our problem solving. This exports a lot of money from farm businesses. Gene editing is now being pushed by many farmers and the farming lobby groups as some kind of saviour to post Brexit farming.

They promise amazing advances such as nitrogen fixing wheat, disease resistant crops, drought tolerant crops (why we need drought tolerant crops in the UK proves how bad our soil management is!), gluten free etc. These are supposed to be provided by small UK companies. This is all well and good, but how will those companies avoid the clutches of bio-tech giants they could theoretically put out of business? It is a lovely thought that small UK seed breeders will provide wonderful traits for the benefit of the population, but I fear they will be bought out very quickly by corporate power of the bio-tech companies. What GE (and GM) are essentially trying to do is fix problems from our reductionist approach to agriculture.

The Green Revolution was touted as a scientific marvel but here we are, with the same problems and awaiting more answers to be provided to us. GE is just a continuation of the treadmill, the treatment of symptoms rather than causes, how long until GE traits get resistance? Not long if you look at what’s happened to chemicals and GM. I will be called a luddite and anti-science for saying all of this, however was it not Albert Einsetin who defined insanity as, “doing the same thing over and over expecting different results”? We are also constantly told we need to ‘feed the world’, this is one of the biggest marketing ploys pushing conventional reductionist agriculture and farmers fall for it day in day out, thus staying on the treadmill. The problem of feeding the world is not one of production, it is of distribution, politics and economics.

On the other side we have regenerative agriculture. I view this as a systems-based approach harnessing nature and understanding soil biology and plant nutrition. We all know farming has been based around the physical and chemical since the green revolution, the biological side of things has been completely forgotten until recently. Great in-roads are now being made by farmers around the world and in the UK. The problem many have with this is the simple trials we are so used to, for example X fungicide works better than Y fungicide on this variety do not work on the highly complicated ecology and biology of the soils we are trying to harness.

If a trial does not say ‘do this’ we don’t do it, its not scientifically proven right? By taking this route we begin to understand how to solve problems. Why does this crop of wheat need five fungicide sprays? Because it is nutritionally unbalanced because the soil biology is not working, because we have pumped it full of ammonium nitrate. Why do we get this weed? Because we have made the growing environment perfect for it because of our agricultural systems. Of course, none of this is quick fix, as said before there are no magic bullets. But an approach to farming that revolves around harnessing the resources we have, soil, air, water and sun in a sensitive manner for me is the only way forward. We need to be using less chemicals.

They are expensive and have unknown side effects, especially to the soil biology and nutrition we are trying to work with. We need to use less soluble fertiliser. Nitrogen use efficiency is very poor on UK farms and it has consequences for the environment. Most importantly for me, as a professional farmer running a business, all this stuff is very expensive. If we can even reduce the amount of bought in inputs by a quarter to half that we use over the next five years imagine how different financial results will look?

Which pill to take? The red pill is a continuation of the treadmill of reductionist 20th century farming where we buy in our solutions which only treat symptoms. Year in year out we do the same thing until resistance or revocation stops us. We then hope we can buy something new to replace the previous failed solution. Great for the people selling the gear, not so much for the farm finances.

The blue pill revolves around finding out the how to solve the causes of problems ourselves. It requires study and knowledge exchange, a degree of bravery and a totally different mindset. It is taking ownership of our production system. It is a mixture of art, science and gut feeling. It is a slow burner and you will not instantly see dramatic results. Over time, as proved by a growing number of farmers in the UK it does work.

The future is incredibly exciting for us. Things like BPS going become trivial when you really start to change your mindset into a regenerative one. If only the industry as a whole spent as much time and money on researching how to harness and improve soil and biology as we do moaning about the loss of neonics and demanding GE, just imagine where we could reach as a collective.

Bring it on, lets make our own luck and reclaim ownership of our agriculture.

Some useful extra reading

‘Chasing the Red Queen’ Andy Dyer

Altered Genes, Twisted Truths’ Steven M Druker

-

Farmer Focus – George Sly

A lot learned from a tough year!

13-5-12,9,0 Our farm in the South Lincs fens is partially above and partially below sea level. Last winter certainly had its challenges, we had flooding on some fields, flooding in my parent’s house and no winter crops on the farm. It was a long winter to ponder decisions for this spring. But in times of despair its often a good point to reflect on how to make changes and adapt for the season ahead. Drainage is something we will be looking ever closer at, but not in the form of all new plastic pipes. We have fantastic drainage systems in the Fens and I can only feel for the farms in the west with the floods.

Our wheat harvest was pleasing and disappointing in many ways. I have realised how important timing is on spraying, having only farmed 2 years I must admit to being a little blasé on timings. All of our wheat was no-till after forage Maize or Beet and we did have Septoria and Fusarium issues which I believe cost us 1-2T/Ha overall. It had potential to be one of our best yields. As a machine maker and Farmer I should tell everyone its all perfect, but we all know that is not true!

Our Sugar Beet and Maize proved to be a big success in terms of margin. Maize for us is a crop that we are using to try and supercharge soil health. As hard as that is to believe we utilise August until end of April to grow big cover crops, maize being a fast growing C4 plant means we can almost have the best part of the year doing soil improvement work but still make the return we need. Using strip till we keep harvest damage to a minimum and usually don’t require any herbicides, insecticides or fungicides other than Roundup at 3L. If we can drop the Nitrogen its organic electricity!

Running a multitude of businesses has its stresses and strains and I have certainly realised how stressful farming can be. In 2-3 years having the hottest summer ever, longest drought, biggest flood etc etc. But we are very lucky to be working in nature.

Clover Companions with row crops – can it replace synthetic nitrogen? Ongoing work…

We have finished a 2 year cycle with clover in row crops. Starting with Rape, then maize and we will now try some wide spaced winter cereals. We used a broad leaf white clover. We established it in June (after forage triticale) then drilled rape 25cm left or right of it, then harvested the rape. We then grazed with sheep hard. Then established Maize into it after trying various chemical and mechanical suppression techniques. Im really encouraged by it, we have seen some rather unexpected positives and negatives. But we will keep this 2 hectare trial running for 7-10 years in the hope we will find a system that can work long term. (photos of clover in rape and maize)

AGROFORESTRY: decision made!

After a long dreary damp winter, I looked at various options for our farm to plan it from now until 2060 when I hope to hand it on to my son. I am 34 years old, and such a decision takes a lot of thought. After many deliberations and a lot of research I have decided to put the farm into an Agroforestry system, incorporating Perennials (Trees and shrubs) with Annual crops. This will be implemented starting in Winter 2020-2021 with the first 30 hectares, and we aim to complete the planting by 2027. The system design for agroforestry has taken me almost 5 years to plan, initially having being inspired by Stephen Briggs farm nearby and a lot of inspiration from Martin Crawford and the late Martin Wolfe. I was lucky to be able to visit some farms practicing agroforestry in the UK, France and the USA to gain some experience and learn about some pitfalls to avoid.

Many people have said to me, George that sounds very risky. But I look at what we do now as reasonably high risk. Another interesting fact when planning the Agroforestry, big is not necessarily better. It would work better if we had maybe 200 acres less for my system. May this be an opportunity for farm sizes to decrease again? Probably not… but it was interesting to come to the thought of reducing in size.

Our system will involve 24 metre alleys of annual crops or rotated pasture with 4 metre under strips. We will lose around 9-11% of our land in total to the tree strips and grass strips. When I say lose… they are far from a financial loss. When the planting is complete we will be growing I believe 3-4X the human consumable calories/nutrition per hectare compared to our current system, we aim to be energy positive and carbon negative (meaning we will sequester more carbon than we emit and we will generate more energy than we consume). We will produce fruit (for drying and fresh), nuts (whole, cracked, oil, flour), berries (dried), medicinal extracts, cereals, meat, energy and building materials. We will monitor the nutritional output per hectare, calorific output per hectare and hopefully link all of that to some metrics/tracking/indices.

Protein… There is a lot of talk about Veganism, anti-meat etc. One reason we will plant nearly 2000 nut trees is that I want some of my customers to be vegan. I am not vegan, I will never be, but I want to embrace veganism and produce products to welcome them. At the same time we will turn our most successful crop (grass) that we cant digest into meat. We hope to integrate poultry in 2026 and rotate them around the agroforestry lanes.