If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

Evolving Benefits Of Using UK Volcanic Rock Dust

Written by Jennifer Brodie from REMIN Scotland Ltd

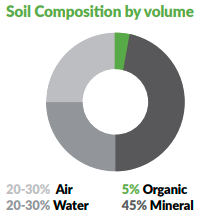

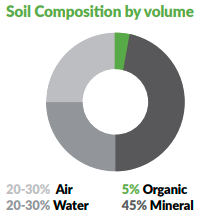

A 5-day FACTS Course at SRUC, Craibstone, Aberdeen confirmed our soil is a mix of 5 ingredients: air, water, decayed organic material, minerals and living organisms. After 15 years working with ancient Scottish basalt, that erupted onto Planet Earth 360 million years ago, before vertebrate life lived on land, I am convinced that it is the interaction of these last 2 ingredients, in the soil, ie minerals and living organisms, that is the key to good health. This is health not only of our soil, but also our plants and animals, ie our food, ourselves and our planet.

As illustrated by Dr Elaine Ingham’s excellent work on the Soil Food Web it is now evident that decades of intensive farming have drastically damaged the life in our soil. The hijacking of agriculture by chemistry over biology has resulted in the loss, or locking up, of our soils minerals and trace elements leaving the soil biology in no fit state to make them biologically available to plants. The McCance and Widdowson paper shows the mineral content of our food crashed drastically from 1940 to 1991. Further exasperated by food processing, this is leaving us overfed and under nourished.

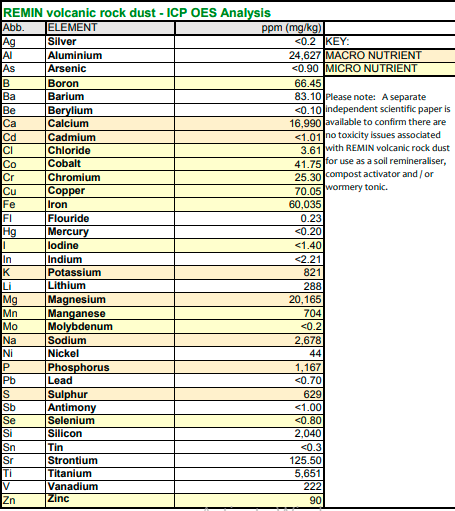

So yes, whilst chemical analysis shows many soils are short of specific minerals and trace elements, I am here to tell you the full quota of 17 are present in REMIN volcanic rock dust – and worms love it! This award winning, organically approved, freshly crushed, finely screened dust is currently sourced from one Scottish Quarry. It shouldn’t be puzzling, but it often is, why the benefits of volcanic rock dust are far more evident when applied to gardens than when applied to farmland. A key farming client is Chris McDonald of Bays Leap Farm, near Newcastle. His application of REMIN was featured in a recent broadcast of Channel 4’s Food Unwrapped when Chris walked the talk with presenter (and pig farmer!) Jimmy Doherty.

The programme included an excellent piece by Sheffield University’s Professor Johnathan Leake where he compared a soil sample from a wood coppice, with the soil in an adjacent cropped field. The difference in soil biology was dramatic with the undisturbed soil in the wood hosting a healthy population of worms whilst the famers field appeared lacking in life. Aristotle told us 350 years ago, worms are the intestines of our soil. As Prof Leake showed in this example, the life in some farmers soil is visually gone. It therefore takes longer to show the dramatic benefits that the gardeners are finding in their less intensively worked and more biologically active soil.

The best farming result I have seen is Warwickshire sheep farmer, Ted Mawby who mixed 4 : 1, by volume, with cow manure resulting in the best pasture Ted has seen in his 24 years of farming. The minerals and microbes in Ted’s mix would appear to be working together to produce exceptional results. Having exhibited at the ace Groundswell in 2018 it was then fabulous to get a 28t bulk REMIN order from John Cherry to mix with his compost windrow. This pile was turned with their new compost turner supplied by BJC Smalley and Co from Berwick and this was demonstrated at Groundswell 2019. Livestock farmer Alex Brewster of Rotmell Farm, in Perthshire has used our products since August 2017. Alex selected one field as a control, applied just REMIN to a second field and REMIN plus cow manure to the third.

When I visited Rotmell, Alex showed me whilst REMIN / FYM application displayed the biggest difference, the benefits of the just REMIN was also evident in the health and the yield of the crop. In Alex’s words “We are clearly onto something and I am particularly keen to follow through on the minerals / microbes aspect of the product.” For 2019 Groundswell I invited Jersey based UK Soil Food Web consultant, Glyn Mitchell of Credible Food to share our stand. We then went straight on to run a minerals and microbes course at the lovely Cabourne Parva Farm in Lincolnshire, that has good conference holding facilities. Here farmer, Peter Kirke, as well as including bulk loads of REMIN in his windrowed farmyard manure, wood chip and silage grass, boosted his compost tea with our product and we look forward to seeing the results.

This August the afore mentioned BJC Smalley took 2 bulk loads. I visited them in September and saw their windrow composting where the REMIN had been added. The photo below was taken by Hughie’s son Michael Leyland, who is a dab hand with the drone camera, of their Windrow mix topped with 2 bulk loads. I have so much more to share including the very topical (and fantastically exciting!) inorganic carbon capture of carbon by freshly crushed rock dust and the organic carbon capture as the soil biology, plant productivity and health increases. We know anywhere in the world with volcanic soil, ie soil close to recent volcanic activity, is exceptionally fertile and productive. With a decade and a half of seeing for myself what REMIN can achieve in gardening soil, all around UK and abroad, all I can say is “Stop havering, and try it for yourself. Just like the gardeners before you, I fully expect you will be back for more!”

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

MZURI SAYS DON’T COMPROMISE THIS SPRING

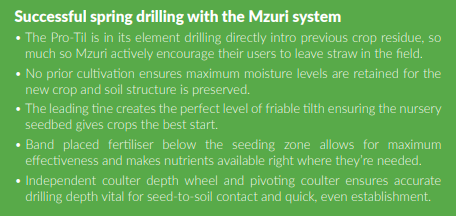

Headed by farmer and engineer Martin Lole, Mzuri is a leading manufacturer of strip tillage seed drills that have been tried and tested on the company’s trial farm since its inception. Formally a conventionally managed farm heavily infested with a high burden of blackgrass and charlock, the Mzuri Pro-Til system has turned the arable enterprise around to become a clean, productive and sustainable farm.

A large part of the trial farms turnaround has been put down to widening the cropping rotation and including more cover and spring crops, something that the manufacturer advocates and is easily achievable using the Pro-Til drill. With the exceptionally poor weather restricting much of drilling during Autumn 2019, the manufacturer suggests getting spring cropping right will be even more important this year. Designed to deliver quick and consistent establishment direct into residue the Mzuri Pro-Til drill boasts several innovative features that make it ideally suited to spring drilling and getting a crop up and away quickly.

Cover crop no problem

Advocating retaining as much surface residue as possible prior to drilling, Mzuri chop and spread their straw with the combine on their trial farm and establish high volume cover crops to provide biomass, retain soil moisture and increase organic matter. As a result, the trial farm has seen their soil organic matter double, thanks to retaining previous crop residue on the surface and allowing nature to take its course. The Pro-Til has been engineered to drill directly into residue such as this, by moving trash out of the seeding zone with the front leg whilst creating a friable strip to seed into. The residue free, loosened strip provides the perfect nursery seedbed for germinating seeds whilst untilled surrounding soil provide the perfect environment for roots to thrive, giving the crop the best start. Drilling into cover crops is made even simpler with the Pro-Til’s staggered layout. Reconsolidation wheels and tine coulters alternate, aiding the flow of residue through the machine, allowing for minimal moisture loss during the critical spring season.

Fertiliser where it’s needed

With a shorter growing season, getting a spring below the seed where it’s needed, with moisture preserved and readily available to activate it. Not dependent on rainfall to wash in any nutrients and being placed in a targeted zone makes for a competitive crop, limiting the nutrient supply to weeds.

Band fertiliser placement holds a whole host of benefits to those in catchment sensitive areas where targeted application reduces the risk of run off and nutrients finding their way into watercourses. The manufacturer also suggests that accurate fertiliser placement can improve the efficiency of applications and gives roots the best chance of uptake where typically nutrient absorption, soil chemical reactions and nutrient movement to roots are generally much slower at lower temperatures.

Consolidate and reconsolidate

The Pro-Til is designed to consolidate multiple operations including seedbed preparation, fertiliser placement, reconsolidation, seeding, slug baiting and harrowing in one pass. With this in mind the manufacturer suggests significant time and fuel savings can be made to drive down costs and improve profitability. Featuring dual reconsolidation from the main centre and press wheels, air pockets are removed and create excellent seed-to-soil contact with many users opting for no additional rolling post drilling.

By consolidating these stages into a single pass, the Pro-Til gives operators greater flexibility to pick their timings and delay drilling to coincide with soil temperature whilst not compromising on quality of establishment.

Accurate seeding depth

Timing is critical, not just in the spring but throughout the crop’s life, from chemistry applications to even senescence. To achieve a consistent crop from headland to headland, Mzuri pride themselves on accurate seeding depth even over undulating ground. Their patented independent, hydraulically pressurised, pivoting coulters ensure accurate drilling depth is retained across the field, promoting consistent emergence in a narrow window.

On their Worcestershire trial farm this even emergence has proven widely beneficial from a crop management and pest control perspective and has evened out inconsistencies associated with their previous conventional system.

Flexibility is ability

With a range of coulter options and leg configurations the Pro-Til system lends itself to a variety of spring cropping options including, beans, cereals, oilseed rape and maize. The popular Pro-Til Select model allows operators to drill on 33cm or 66cm row widths at the switch of a button. Coupled with single or dual band coulters, or the Xzact singulation seeding unit the Pro-Til is a versatile solution for a range of soil types – whatever the season.

-

Farmer Focus – Steve Lear

Mother nature was going to give me a kicking at some point!

Since starting our no till journey, a couple of years ago, I haven’t really had too much to complain about. We have had two easy autumns where we were able to get a decent amount of ground drilled without too much of an issue. Its been two of the driest years that I can remember and that tends to favour no till. Our yields haven’t really been any different from when we were cultivating, in fact if anything we have seen a yield increase on some land and certainly in winter barley. So, I knew at some point mother nature was going to throw us a curve ball. But instead of a curve ball she pitched one up straight into the goonies.

The soils at the end of harvest were in a great condition and I was looking forward to a nice easy autumn of drilling as soon as we got a chit on some blackgrass. Unfortunately, the weather had other plans. When it eventually started to rain it didn’t really stop and this has caused havoc with our drilling plans. The ground has never really dried out enough to get on it in our area. A few farms have mauled crops into cultivated land but we soon learnt after trying to travel on wet soils that we were going to have to call it a day with only 150acres drilled out of 1500 planned. We didn’t want to undo all the great work that we had done in the past couple of years for the sake of a poor winter crop and a 12-ton drill on wet clay is not very clever.

On the plus side, some of our cover crops look great. We established an oat and mustard mix behind whole cropped wheat in July which is now nipple high and has some fantastic roots on it. We have a multi species cover crop over 150ha with mixed results depending on how early we got it established. The idea was to graze all our covers this year with some neighbour’s sheep, unfortunately the persistent wet weather has meant that we didn’t dare let livestock on the fields as small feet on saturated clay would have resulted in a compacted mess.

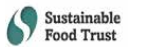

The weather has however meant that I’ve had the time to go around the farm and do a lot of soil sampling and testing.

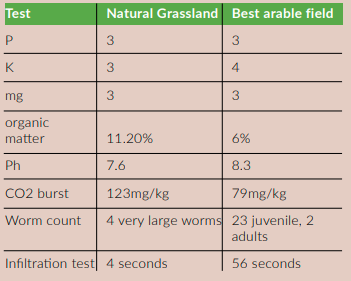

The following tests were carried out on a field by field bases: An infiltration test, A worm count, slake test, a photo of the structure is taken and a soil sample is sent off to NRM labs to carry out their soil health suite. This includes tests for: Ph, P, K, mg, Organic matter, Co2 burst and textural classification. This year I have also been testing an area on the farm that has been in a natural cycle for as long as I can remember. It grows chest height grass every year and has zero management. I will use it to bench mark my soils across the rest of the farm to see where the soil has the potential to get too.

The infiltration test on the natural area showed that we have a way to go with our soils in terms of improving them. I couldn’t believe the amount of water I could pour into the pipe on the natural area before it started to back up. We will also be doing all we can to raise organic matter across the farm by using grazing stock, cover crop and manure applications. The other interesting observation from doing these tests was that the natural area had very few worms in compared to the arable land, the few worms that were present were enormous though.

We over seeded a large percentage of our grazing ground again this autumn by grazing the sward tight to the ground and then drilling grass seeds and herbals into it before the rain hit. We drilled the fields with cattle still grazing in them, the cattle were moved on after a couple of weeks to let the new seeds establish. This system works really well for us and means fields aren’t shut up for reseeding for long. It will be interesting in the spring to see how the herbal plants do against the grass. I’m hoping they will keep growing throughout the summer when the grass starts to slow up as they tend to have deeper tap roots.

It’s been a frustrating autumn but we aren’t in as bad a situation as some that I’ve seen in the farming press. It must be heart breaking seeing your farm and livelihood under water and my thought go out to the families affected by the flooding around the isle. Stay strong and keep your fingers crossed for a friendly spring.

-

Future Farming Technology From John Deere

There have only been a few times in my life I have been truly wow’d at an agricultural show. But I certainly have one more to add to the list after visiting the John Deere stand at Agritechnica 2019. As always, the stand was big, and we were very lucky to have Nathan Kramer from the USA to show us around the new X9 combine. Although Nathan left out a lot of the still to be announced details we really wanted to know! But it was stepping into their future technology zone that really captured the imagination. Its was a mix of real world and possible solutions for farming. It was, however, all very people centric. Tools to help farmers do a better job, not tools to replace farmers. This was a nice thing to see.

Here is a little walk around the Future Technology Zone and a little bit about each of the displays.The biggest drone I have ever seen!

On show was a demonstrator model of the VoloDrone equipped with a John Deere crop protection sprayer, which is ready for its first field flight. Offering a potential payload of 200kg, the VoloDrone is able to cover a big area, even when ground travel conditions are far from optimal. The drone is the result of a collaboration between John Deere, who bring the requirements of farmers and the Urban Air Mobility pioneer Volocopter, who are working on producing flying taxis for moving people from A to B. While small drones are already being used commercial in China, large drones in agriculture where you are trying to spray bigger areas could be the way to go. The VoloDrone is not limited by topography, spraying hillsides would be much easier! But it could even be used for sowing seeds.

The VoloDrone is powered by 18 rotors with an overall diameter of 9.2m and features a fully electric drive using exchangeable lithium-ion batteries. One battery charge allows a flight time of up to 30 minutes. The VoloDrone can be operated remotely or automatically on a pre-programmed route. The main issue of course being that in the UK that the aw does not allow us to use drones to drop anything from the sky, but by the time our learned government get round to changing UK legislation I would imagine this technology will be ready.

See and Spray – Blue River

Continuing on with the spraying theme, but applied in a more conventional matter, John Deere introduced Blue River’s “See and Spray” technology. The aim of this software is to save 90% on herbicide usage by only spraying weeds that are identified while opening the potential to use other herbicides that are not appropriate for blanket application.

How it works:

Sense & Decide – their machines see every plant and determine the appropriate treatment for each. They have developed intelligent models using computer vision and machine learning that can distinguish subtle differences between plants and weeds of many species and sizes. See & Spray does not rely on spacing or color to identify weeds. Instead it has the ability to recognize differences between plants in conditions that would challenge even the human eye. Robotic nozzles target unwanted weeds in real time as the machine passes. With great accuracy and precision, See & Spray applies herbicide only to weeds, avoiding chemical application on the crop or on areas without weeds. Precise application allows growers to reduce chemical usage significantly and unlocks the ability to use herbicide alternatives to effectively control weeds that would otherwise be resistant.

This is the sort of spraying pattern you get:

Watching the demo on the John Deere stand and talking to the Blue River staff made you realise how close this technology is to being available. And right next to the demo was an autonomous sprayer!

Autonomous Crop Sprayer

John Deere’s autonomous crop sprayer has a 560-litre spray tank. The high ground clearance of 1.9m and fourwheel steering make it extremely versatile, while the front and rear tracks minimise ground pressure and greatly extend the operating window. Just imagine this sprayer fitted with Blue River See and Spray technology.

Smaller “Hive” Technology Drones

While the Volodrone might be the right for certain farms, the ability to spot spray using smaller drones in fields will appeal to other farms. These smaller drones are equipped with weed identifier software and crop sprayer nozzles, allowing weeds to be identified from the air and then specifically targeted. The 10.6-litre tank is filled fully automatically at a vertical docking station, where the battery is automatically charged as well. Flight time with a fully charged battery is 30 minutes. The big advantage of this drone is the precise application of crop protection products, reducing the volumes used. This “stack” of smaller drones can be towed to the field and then controlled by a single operator (laws permitting) while that driver is doing something else in the field or adjacent field.

Electric Autonomous Tractor

John Deere’s new autonomous tractor concept is an electric drive unit that can attach to implements a farm already owns. The tractor has an output of 670hp, so will be able to pull most implements on a farm and can be equipped with either tracks or wheels. Where more weight is required, it can be ballasted up to 15t. In lighter trim without ballast, it has the ability to help reduce soil compaction. Thanks to the electric drive, there are no operating emissions and noise levels are extremely low.

Further advantages include low wear and maintenance costs that accompany all electric vehicles. No information was available at the show on running times and recharge times, but as with all concepts, more details will emerge over the next few years. If you have multiple tractors on farm, I can see the possibility to change one of them to this sort of electric tractor would be appealing in the future. As always, it’s this transition period in the adoption of technology that presents the biggest issues on farms.

John Deere’s Futuristic Command Cab Control Centre

We were introduced to Neil Macer, John Deere’s product manager for this project, who gave us a tour of the technology being employed within the Command Cab. This isn’t a operational system, but more a vision from John Deere of how a future cab employing artificial intelligence (AI) could be operated by farmers. With its central touchscreen display giving full farm visibility, networking of all machine components, John Deere presented a vision of how a connected farm could operate. It integrating real-time weather data, all machines on the farm or within your contracting business, individual machine monitoring and job management, the cab becomes the command centre for all agricultural operations. Equally this information could also be available in the farm office. Vertical digital satellite and fuels displays were also on the A pillars and a secondary curved screen also spanned around the top of the cab. Plenty of screen space to have The Farming Forum live on the screen at all times!

Summary

We spent over two hours talking to the John Deere staff in the Future technology zone. The fact they were showing these new ideas at Agritechnica means we are unlikely to see any of this technology on farm within the next 5 years, but you couldn’t help being enthused by the possibilities available in agriculture. If children in school saw this, I think the idea of a career in farming would be a lot more appealing. It really is an exciting time to be a farmer.

-

Base-UK

BASE-UK was established in 2012 and is independent of all businesses or organisations. We provide a forum for members to share information, experience and ideas on conservation agriculture, which includes topics such as minimum tillage, direct drilling, cover cropping, integration of livestock and many other techniques offering more sustainable agriculture by working in harmony with soils and the wider environment as well as inviting industry experts to speak to members.

BASE-UK shared a stand at CropTec with Direct Driller Magazine and the Farming Forum and jointly hosted “Soil Hubs” where some of our members stood on a panel for Q&A discussions on Integrating Livestock into the Arable System; Cover Crop Strategies and Widening the Crop Rotation. These were well received and provided a great opportunity to encourage the audience to take part and ask questions with farmer to farmer knowledge transfer being key as per the principles behind BASE. Thanks to Steve Lear, John Cherry, Angus Gowthorpe, David White, James Warne, Tom Storr, Andrew Jackson, Clive Bailye and Adam Driver for their contributions.

As this is written, a group of 20+ members are visiting Frederic Thomas along with Frederic Remy and other farmers in France for a knowledge exchange trip and to compare notes on how to cope with the wet conditions experienced this autumn (and of course to sample the local culinary delights).

Details about our upcoming AGM Conference in February 2020 are on our website www.base-uk.co.uk We have a variety of different speakers including Dr Sam Cook, Dr Anna Krzywoszynska, Professor Adrian Newton, Dr Lea Herold and some of our own BASE-UK members including SFOY Julian Gold.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

WET YEARS ARE NO GOOD FOR DIRECT DRILLS

Oh dear! RAIN, RAIN, RAIN.

“A wet seasons no good for direct drills LAD” is the chant we hear incessantly, often with no experience of any Direct Drill. Yes it is, unworked stubble stands more water than worked, cover crops stand much more water than anything else and provided the tractor is suitably tyred and you’re not damaging the structure, if it’s not balling up on the wheels then we CAN direct drill. Image 1: Drilling Winter Barley in wet wold land as the storm clouds gathered, if only we knew! This crop is establishing as well as conventionally drilled barley in the next door neighbours field, but for a much lower cost, financially and structurally, they had 6 metres and 300hp, here we have 5 metres and 150hp. Versatility and adaptability has to be the name of the game in a wet season, the Ma/Ag can work in any direct drilling situation and can drill on any kind of cultivation, even straight onto ploughing.

Image 2: The Ma/Ag wide rubber press wheel, means the drill is riding on rubber equivelents to more than ¾ of the drilling width, it travels even on fluffy soils like this one and leaves a firm finish with seed in the right place., the fields rather than the bag !

Image 2: Here we prove that a grass ley can easily be direct drilled, grazed as late as possible, no disturbance and maintaing soils structure, its just coming out now, quicker than some ploughed and power harrowed land opposite !

Updates on the crops next time.

For more information, contact

Ryetec, 01944 728186 -

Carbon Footprinting

Written by Becky Willson from the Farm Carbon Cutting Toolkit

The old adage of you can’t manage what you can’t measure is certainly true of carbon accounting.

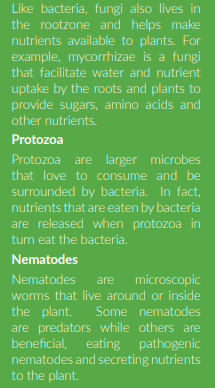

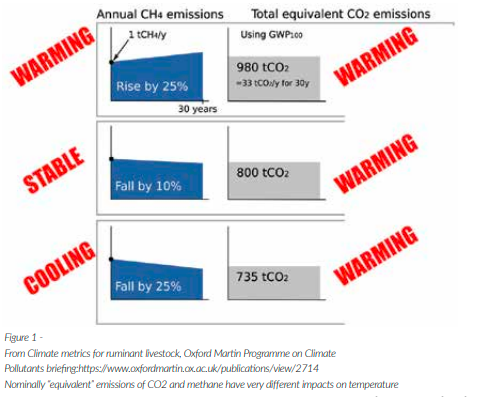

But when it comes to agriculture, measuring carbon isn’t as simple as it may first seem. The variation of emissions and carbon stocks are due to the fact that we are trying to measure biological systems, which are impacted by climate, soil type, topography and vegetation, as well as what we as farmers are doing in terms of our management. Which makes the whole thing a little tricky. However undaunted by this complexity, carbon metrics are an essential tool that farmers can use to not just identify climate solutions, but also to baseline the farm’s emissions and drive technological change. Identifying the carbon footprint of a farm business is the first vital step in being able to quantify the contribution that the farm is making to climate change. A carbon footprint calculation identifies the quantity and source of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide emitted from the farm (as well as carbon sequestered in soils and woodland) highlighting areas where improvements or changes can be made to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Unless you have been hiding under a rock recently, you can’t have failed to notice the increased attention that the carbon credentials of farms has been receiving. Whether it is a way to assess the sustainability of one diet choice over another, or a report on the often outlandish claims of livestock production systems, carbon is everywhere. But what does it really mean for the farmer, and is there truth behind the rhetoric? Greenhouse gases are much talked about but they are inherently intangible. You can’t see, taste, hear or touch them; and they are all gases that are released in relatively small quantities on a continuous basis. So how do we understand what is going on with them and how do we talk a common language?

Outside of agriculture and when looking at reports, emissions are commonly communicated about as carbon emissions.

However on the farm, carbon dioxide isn’t the main issue, it is mainly the emissions occurring as nitrous oxide and methane which are not just a larger part of the emissions attributed to farms, but are also more potent in terms of their effect on the warming climate. In order to make sure that we are all talking the same language, all emissions are converted into a carbon dioxide equivalent (with methane being 30 times more potent and nitrous oxide 298 times more potent than carbon dioxide). By converting them all to carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e) we can talk in a common language about kilos or tonnes of CO2e.

Reducing carbon emissions in a farming business makes sense on many levels. High carbon emissions tend to be linked to high use of resources, and / or wastage, so reducing emissions also tends to reduce costs. This makes the farm more efficient and should improve profitability. As well as the business opportunities that come from reducing emissions, farmers and land owners are in the unique position to be able to sequester carbon both in trees, hedgerows and margins and within the soil. Before being able to reduce emissions, you need to know where the emissions are coming from. Are the largest emissions coming from livestock, soils, fuels, or fertilisers? It is vital to get a picture of your business which is made possible by carbon footprinting.

Choosing a tool to use

There are various carbon footprinting tools that have been designed for use by individual farmers (or groups of farmers) who are interested in understanding what is happening on-farm. Although the simple principle of completing a carbon footprint assessment is the same (emissions minus sequestration equals footprint), within that there remains variation between what scope and boundaries the tools use to calculate the results. Boundaries of a calculation determine what aspect of production is being assessed; for example whether you are calculating the emissions associated with one farm enterprise or the whole farm, or whether it is assessing operations within the farm gate or taking account of what happens off farm. A key part of deciding what tool to use centres around what you want to use the footprint for.

Marketing – if you are wanting to use the results for marketing purposes, it is a good idea to choose one that has a clear method attached to it, which sets out what is included and excluded from the calculations, that way you can be completely transparent about your carbon credentials. A management tool – if you are planning on using the results and the data as a management tool, perhaps to highlight areas to improve in the future, then you will want to use a tool which allows you to evaluate the impact of changing your management. These tools tend to need more data added in at the start so that the impact can truly be seen. An interest – if you are just interested in what might be happening in carbon terms on your farm, then again choosing one that explains clearly what is included and omitted, and shows the footprint broken down into key areas is a good starting place.

Sequestration – in or out?

A key question to look at when footprinting is whether carbon sequestration is included in the calculation. Carbon captured within trees, hedgerows and field margins as well as the carbon held in soil is an important part of the footprint and shouldn’t be overlooked. If the tool doesn’t include sequestration then the footprint will be looking at the negative without the positive! There are a range of options that start from free tools that can be used in the farm office to paid for services that come with an advice service attached to them with recommendations for the future.

There are some supply chains within agriculture where carbon footprinting is already taking place. Most dairy farms are already being foot printed as part of their milk contract, however in other farming sectors the take up has been slower. Tools include the Cool Farm Tool, AgreCalc (which is used in Scotland) and the Farm Carbon Calculator. The golden rule is, once you have decided what tool to use, stick with it, as there are differences within the methods used in each calculator, so comparing results between calculators is meaningless.

Getting started

Once you have decided which tool you are going to use, the first step is to gather all of the input data. This includes information on fuel use, livestock numbers, fertiliser inputs, use of materials, waste produced etc. In order to be accurate you need to be comprehensive in your assessment. The list can look daunting at first, but if your record keeping is reasonable then this process should be achievable in a couple of hours. One you’ve done it, the next time will be quicker! Once you have the data, it’s just a case of entering it into the calculator, which shouldn’t take more than an hour, after which you should have a breakdown of carbon emissions by sector, both in amounts (kg or tonnes of CO2) and percentages of the total footprint by category. Armed with this data you are then ready to think about how to reduce emissions and increase sequestration.

When completing a carbon footprinting although value can be seen from completing it as a one off exercise, the really interesting part comes when the process is repeated at regular intervals, usually annually. When you do this you can start to see what direction the farm is moving in and whether the actions you’re taking are working.

Emissions sources

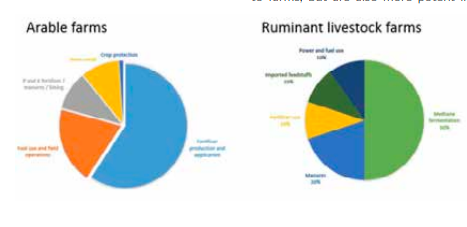

Although each farm will vary in its carbon footprint, the charts below show the average breakdown of emissions across a typical livestock and arable farm.

Next steps

So once you have the footprint of the farm, deciding what to do is the next key step. The footprint result will be reflected as a carbon dioxide equivalent, but should also show you where the emissions of nitrous oxide and methane are produced. Key areas to focus on are the management of soils, fertilisers, manures, livestock, cropping, energy and fuel. There are numerous opportunities to reduce emissions and costs as well, leading to improved resilience and profitability, as well as opportunities to improve carbon sequestration and soil health, the ultimate resilient business model! Absorbing more carbon than the farm emits is a goal that all farmers could work towards and understanding the farm’s current carbon position by footprinting is the first key step.

Currently agriculture is one of the only industries within the UK which is under voluntary greenhouse gas emissions reductions, however we are not going to be in this position for long. The spotlight is being well and truly shone at agriculture’s carbon credentials at the moment, and this offers an opportunity for us to take the first step and understand what is happening on our individual farm, and what we can do to improve profits, reduce emissions and build soil health and sequestration. Carbon offers a fresh lens through which to evaluate our business and build resilience for the future.

Footnote – Farm Carbon Cutting Toolkit – which provides practical help and advice to farmers on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving energy resilience and building soil health. FCCT’s carbon calculator has been designed by farmers, is free to use and the new version will be launched at the Oxford Real Farming Conference in January 2020.

-

Investigating The Combined Effects Of Tillage, Compaction And Cover Crops On Soil Health, Yield And Controlling Grassweeds In Spring Cereals

Written by David Purdy from John Deere, based on work at Agrovista’s Project Lamport

A project, now in its 7th year, initially developed and managed by industrial partner AGROVISTA to study the cultural control of blackgrass at their flagship Lamport trials site in Northamptonshire used cover crops in conjunction with spring cropping to develop a rotational production system to manage blackgrass populations on heavy soil types. Early observations and successes suggested as well as controlling blackgrass, reducing headcounts from over 500m2 to less than 2m2 for example, the soil also improved as well as maintaining sustainable spring wheat yields. To study these effects further a larger fully replicated trial site has been developed at the same location. The background to the trial focuses and expands on the findings at Lamport along with some of the wider significant challenges and limiting factors on cereal yields and profitability in the UK. These include declining soil organic matter and soil health, soil compaction and obviously grass weed control. After soil organic matter reduction, soil compaction is one of the most damaging factors for plant growth and yield.

As machinery axle weights increase further deeper compaction is inflicted on soils resulting in further subsequent damage. However modern tyre technologies and lighter axle weights can help mitigate the damage. Tillage is used to break up the compaction and restructure soils to enable crop growth and development but often has further damaging effects for example the further loss of soil organic matter with the associated negative effects. Finally, the blackgrass issue has grown out of post emergence herbicide resistance and therefore increasing populations which has made control in winter cropping of cereals more challenging, therefore, spring cereal production systems are often used as a cultural control mechanism to help deal with blackgrass.

The use of cover crops is growing in the UK, however their scientific understanding on the effects on soil health factors, spring cereal crop yields and their part in blackgrass control is limited. This trial using large replicated field trials running from 2018 – 2021 will investigate the effects of low disturbance tillage, different levels of compaction, lower axle weights, modern tyre technologies and cover crops in a spring cereals production system. The overall aim is to understand the combinations of physical treatments with the biological impacts of plant rooting systems of cover crops to improve soil health, ensure resilient yields and control blackgrass in a spring cereal production system, in summary the roots verses iron philosophy, allowing at capture of carbon through photosynthesis to feed the soil food web which in turn delivers gains to soil health.

Two large replicated trials have been established. The first, fully replicated 32 plot experiment, established in 2018 compares the effects of low disturbance tillage at 20cm and zero tillage with the biological effects of cover crop species black oats and phacelia grown both individually and combined.

The second fully replicated 48 plot experiment established in 2019 compares the effects of pre compacting the soil at two different tyre pressures on lower tractor axle weights, low disturbance tillage at two different depths with the biological effects of black oats and phacelia cover crops combined. Along with control plots and replication these trials result in a large 96 (12 metre x 12 metre) plot trial site.

Their effects will be assessed with range of physical and biological measurements including water infiltration rates, soil structure, bulk density, penetrometer resistance, shear forces, organic matter, worm numbers, decomposition rates, mycorrhizal colonisation and yields among others. Were appropriate precision farming technologies such NDVI and telematics are being employed to measure cover crop biomass and fuel consumption.

The objective is to build a production system that improves soil health and in turn resulting spring cereal yields and well as managing blackgrass to low levels. Early results are showing some positive results including,

• Worms are increasing under cover crops but declining under tillage.

• Soil structure and aggregation are improving under cover crops.

• Spring wheat yields are improving after good cover crop biomass production

• Blackgrass control improves after cover crops

• Combinations of cover crop and low disturbance tillage has yield benefits to subsequent spring cereal yields

Along with specialists from Agrovista the project partners include Philip Wright from Wright solutions and well as various specialist machinery providers. The research forms part of a PhD programme at the University of Nottingham. Project Lamport has open days in July where further details and result will be presented

-

Using Wildflower Strips For Pest Control

It is easy to paint a bleak picture about the future of agriculture both in the UK and globally. Whether its pesticide use

and insect declines, run off and water quality, or greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, it seems like every

week there’s another negative news story about farmers and the UK countryside. But whilst widely rounded upon as

the villain, farming is uniquely placed amongst business sectors as it also holds the key to helping solve many of our

environmental challenges.It is easy to paint a bleak picture about the future of agriculture both in the UK and globally. Whether its pesticide use and insect declines, run off and water quality, or greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, it seems like every week there’s another negative news story about farmers and the UK countryside. But whilst widely rounded upon as the villain, farming is uniquely placed amongst business sectors as it also holds the key to helping solve many of our environmental challenges. Whilst I may be hopeful, growers are still facing a fearsome trio of issues – issues that pose a serious risk not just to their profits but to the nation’s food supply. First, over-reliance upon plant protection products has led to many pests becoming resistant to insecticides. And resistant insects in our fields means spraying simply becomes an expensive activity that serves no benefit, and in fact, will just cause unnecessary environmental harm.

Some might suggest that to fill this void that we can just develop new products, but this leads to our second problem. That there are few new actives progressing along the product development pipeline, particularly in minor horticultural crops, which often have to rely upon Extensions of Authorisation for Minor Use to tackle pests. And the third issue is the increasing legal restrictions upon products used to control insect pests – and the direction of travel is such that all products currently on the market will, at some point, likely also become subject to such restrictions. Time is therefore running out on the way that we currently farm, and It makes sense for us to find alternative methods of farming that don’t require us to rely on pesticide applications every year to remain profitable.

Conservation biological control has been suggested as a tool we can deploy which can relieve some of the pressure on plant protection products. This branch of biological control works by manipulating the habitat around crops to help support a group of beneficial insects often referred to as natural enemies, which includes the likes of ladybirds, hoverflies or ground beetles that naturally prey on pests. Typically, these resources are provided by plant mixes that we put into fields, traditionally either flowering field margins or beetle banks. By providing these potential allies with shelter, nectar, alternative food and pollen, the idea is they then move into the crop to eat pests and reduce crop losses. In high-value horticultural crops, there is even more pressure than in combinable crops to combat pest outbreaks and one crop I’m interested in particularly is carrots. In the UK, we normally grow 97% of the carrots we eat (unless it’s a summer like 2018 and carrots might yield up to 30% less).

This means that any improvements to the sustainability of the crop mean real improvements to the UK countryside. For me though, this isn’t just a source of national pride, but actually is about taking responsibility for our food production and not just offsetting any environmental harm elsewhere. A big problem in carrot fields are the viruses which aphids transmit. These viruses can cause seedling death or impact carrot quality as the roots become split or visually diseased and can’t be sold. 2015 was a bad year for virus outbreaks, with carrot growers losing up to 15% of their crop. This cost the UK carrot industry £20 million, which is around 6% of the industry’s total annual sales.

As a result of this, in 2017 a PhD project was set up with an industry focused goal from the outset: what are the best plants we can sow to support natural enemies in carrot fields? With a willing partner in carrot farmer Ben Madarasi (who had already been conducting his own trials in Huntapac fields), we narrowed the problem down further: as carrot crops sown in early April are particularly susceptible to viruses. As Huntapac typically farm rented fields only available from Spring, it hasn’t been possible to establish perennial flowering strips. Therefore, we have been sowing plant mixes in the spring as the same time as the carrot drilling; using species that we know will rapidly establish to provide vital resources to the natural enemies.

This limitation is a good example of the sort of issue that might not arise in a typical academic study, and by working with commercial farmers, we can also investigate which plant species ultimately have a positive effect on crop quality and ultimately profits. This is an important component of the work as if we are taking land out of production, ideally, we want only to offset the loss of land with increased carrot quality.

We are also studying where the best place to put these flowers within fields. We know that these flowers have a ‘spill over effect’. Where the natural enemies attracted by the mixes will move out from the flowers into the crop. But this effect decreases the further we get away from the flowering strips. So, we’ve trialled putting these into strips straight into the middle of fields, to deliver the natural enemies closer to where the pests are. We’ve found this year, working around machinery widths and Huntapac’s operational needs, that we can do this successfully! We are working to show that increasing natural enemy numbers in fields should help to reduce pesticide sprays.

There is a growing body of literature that raises concerns about the impact of some agricultural practices, such as insecticide use and changing land use, upon wildlife like our insect populations. Even though carrots are harvested as roots that don’t benefit from pollination, these concerns have led to businesses like Huntapac wanting to farm in ways that are sympathetic to pollinators. As such, we have also been trying to support wild pollinators like bumblebees and solitary bees as these are not managed like honeybees. Without that careful management, there is a concern that wild pollinators are struggling to find enough nectar in early spring and later summer. Therefore, we are also trying to pick species for the strips that are still flowering in August and September. Readers of Direct Driller will also be aware that as the plant mixes sown include species like clovers, mustard and phacelia, there may also be improvement for soil health under the strips. Which all goes to demonstrate a key feature of these flowering strips – they are multi-functional, which will hopefully help to increase their uptake on farms.

We’ve been collecting data on how well the plant mixes have established and know which ones establish quickly. The insect communities at the mixes are well studied too, we know which pollinators that have been visiting which flowers throughout the summer. We also carefully monitor the pest population to make sure we aren’t unintentionally increasing their populations too. We have now developed a technique for assessing the carrot quality next to the flowering treatments and we are finding differences between the plant mixes we are using. After two years of successful trials on Rothamsted Farm in 2018 and 2019 and a 12-hectare field trial in one of Huntapac’s commercial carrot fields in Shropshire, we are building up a body of encouraging results! Over the coming year, once we’ve had a chance to properly analyse the results, we hope to shaper our findings with the farming community – so stay tuned!

-

Introduction – Issue 7

A very warm welcome to this new issue of Direct Driller. There’s much to get your teeth into, including topics that are new but highly relevant. A glimpse into the future shows new crops on the cusp of becoming commercial. Why, for example, have we yet to realise the potential of rye? And in the longer term, what are the chances of growing perennial wheat in the next 20 years?

I like magazines which surprise me, and this one certainly does, with topics far removed from data technology, satellites, drones, robots etc. Here we have features which look at progress and technology which have yet to hit either the farming or national press headlines. This issue has its feet very much on the ground.

Contributors have real experience and expertise in both the practice and science of using and managing soil. Those planning to start No-till will find James Warne provides dozens of tips on pg 56. On pg 84 Andy Howard has some startling figures about real farm profitability. Those farmers whose cropping is restricted to the three cereals and osr may well find ‘buckwheat’, ‘phacelia’, burseem clover’ and so on somewhat daunting. Yet they make a valuable contribution to farming systems, so it’s worth getting acquainted with these strangers!

This issue of Direct Driller shows that the pace of change in the industry is not confined to electronics and mechanics. Once again we must thank those very many people in companies, institutes, universities who choose to support us, and of-course the numerous farmers who share their thoughts and farming methods. They all help to make this publication essential reading.

If you have something important to say do please get in touch with Clive or Chris – info@directdriller.com or me – mike@farmideas.co.uk

-

Featured Farmer – Jake Freestone

Farm Manager at Overbury Farms

The Farm

Overbury Farms is an integrated part of Overbury Enterprises which has been in the same family for over 250 years. It is a mixed farm that produces a range of crops including wheat, barley, oilseed rape (OSR), pease, linseed and soya beans. We also let out certain areas of our farm to specialist growers who produce crops such as onions and peas. The farm also has a flock of 1,200 sheep and home-bred Texel Cross Mules. The ewes are a mixture of Mules, Aberfields and Lleyn crossed Romneys. All lamb is LEAF marque certified which is an environmental assurance system that recognises sustainably farmed produce. Produce and livestock are sold to high street supermarkets as well as local markets and food outlets. OSR is sold on to Unilever and our barley is harvested and sold to Molson Coors.

Watch a video by scanning the QR Code opposite (recorded at an intercropping event) of Jake introducing the farm and talking about the importance of no till and cover cropping.

Sustainability In Practice:

Building soil fertility and reducing weeds through carefully planned rotations, no till, intercropping and cover crops The 6 year rotation at Overbury includes winter and spring barley, OSR, winter wheat, peas, linseed and soya beans. We have reintegrated livestock and now graze ley mixtures with home bred Texel, Abermax and SufTex lambs. This has the benefit of breaking weed lifecycles and also allowing the restorative periods in the rotation.

The system has been no till since 2013 (on some trial blocks, most of the farm came in from July 2015), which has had a very noticeable impact on soil quality, infiltration and biology – evidenced by some giant worms that we have found here lately! On most occasions we leave some straw and use mollasses and humates to help break it down. I don’t use seed treatments as the effect on mychorrhizzae is compromising the essential life in the soil, and instead have farm-saved untreated seed (seed is tested for fusarium mainly and if clean enough it’s not dressed).

If the soil is going to be uncovered for more than 5 weeks, I will put in a cover crop. In monoculture there is no room for genetic variation. A field of wheat is full of genetically identical plants and everything is vulnerable to the same pests and diseases. In a crop mixture you can guarantee that something will grow regardless of what conditions come your way. But it is not so much what happens above ground as below. Speaking to fellow Nuffield Scholar Andy Howard, I was inspired to give companion cropping a try…

Our most common species mixture (or ‘plant team’) is OSR, vetch and buckwheat. We have 4 hoppers on the Cross Slot drill (one also for slug pellets) and drill it at the same depth in the autumn – seed rates of approx. 7kg buckwheat, 2.5kg OSR and 13.5kg vetch per hectare (ha). As we found we were attracting a lot of pheasants in the crop, we are now using a mixture of 2.5kg/ha OSR, 2kg/ha burseem clover and 10kg/ ha vetch. Each species has different functions in the mixture. The vetch is deep rooting and breaks compaction to open up the soil for the OSR and also provides residual nitrogen; the buckwheat is good for creating a cover to smother weeds, making phosphate more available and distracting pests as well as providing a structural function to stop the crop going flat.

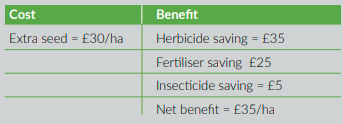

In these mixtures we use no pre-emergence herbicide as we rely on the competition effect to smother broadleaf weeds. Astrocurb is the only broadleaf herbicide we use to kill off the buckwheat and vetch and stop them growing over. Frost will take out buckwheat at less than 5˚C. A simple cost benefit analysis shows that despite the higher costs of seed, we are saving approximately £35/ha on inputs with the intercrop versus a monocrop of OSR.

We also undersow a mixture of red clover, perennial ryegrass (PRG), plantain and chicory into spring barley. This year we had a yield of 6 tonnes / ha with no herbicide. I deliberately chose those fields that have a brome problem to help get on top of it. This then goes into a 2 year ley for sheep. Another mixture we are trying is kale undersown with white clover for fattening lambs. Once grazed we then direct drill winter wheat into the white clover. I am interested to continue experimenting with this – an understory of white clover for the whole rotation would be good. One example of this experimentation was a recent cover crop of rye, vetch, phacelia, and buckwheat drilled into soya ahead of soya beans which were planted the following spring. The cover crop provided a valuable habitat for pollinators in November when there is not much else available.

I am pleased to say that blackgrass is now a diminishing issue – it’s now just a spot of leisurely hand rouging on a Sunday afternoon! I think this is a combination of 5 years no till, spring cropping and having a cover at all times (if the soil is going to be bare for more than 5 weeks I put a cover in). We also try to drill later but I am cautious not to push it back too far in a no till system – although the soils are drier. There are barriers to farming in this way – there are some machinery requirements; we need to consider the rotation effects and limit the ‘green bridges.’ Finding markets for crops such as buckwheat is also a challenge, as is important to get spring crops to contribute enough to gross margins… But I think the biggest barriers are in our minds! Have to stop worrying what the neighbours will think and take the plunge and try something new…

Motivations:

Overbury Farms became a member of LEAF in 2003 due our core belief that intensive farming also needs to be environmentally sustainable. We then gained LEAF Marque status in 2007 and we proudly became a LEAF Demonstration Farm in 2012. This allows us to promote Integrated Farm Management (IFM) and show our strategies to achieve sustainable farming with the agricultural supply chain as well as the local community through farm visits. LEAF membership has helped us implement many strategies in order to enhance yields while being conscious of the environment.

In 2013 I was awarded a Nuffield Farming Scholarship to study the possibilities of growing 20 t/ha of wheat in a sustainable farming system while following IFM – ‘Breaking the Wheat Yield Plateau in the UK.’ Through this project I visited several countries including Canada, Mexico and the United States to understand the limiting factors of high yielding wheat crops and what the main mitigation strategies were that were in place. Differing climates produces a range of challenges when faced with growing high yielding wheat crops and this project allowed me to witness these problems first hand and to bring solutions back to the UK with the potential to use them on British wheat crops. One of the big eye openers for me was to realise that we are in fact abusing the soil by overcultivation. I came to the conclusion that we need more diversity to enable us to overcome some of these challenges. Increased soil management, more diverse rotations and livestock integration are all key to increasing wheat yields.

Farmer Tips

• Always keep soil covered.

• Consider what your objectives are with mixtures before selecting them i.e. weed suppression, increasing protein, combating pests and diseases…?

• The biggest barrier is in your mind!

Farm Facts

FARM SIZE: 1,538 hectares

MANPOWER: 6 full time staff

FARM TYPE: Mixed

NUMBER OF LIVESTOCK: 1,200 sheep

TENURE: Owner occupied

REGION: South West England

RAINFALL: 843 mm

ALTITUDE: 229 m – Bredon Hill Summit

SOIL: Brash

APPROACH: Integrated Farming

KEY FARMING PRACTICES: No Till Trap crops Mixed farming Companion crops Cover crops Diversified rotation Intercropping

-

No-till by Numbers

We are often asked how much of the UK’s farmed acres are direct drilled. It isn’t easy to answer exactly, but the easy answer is that it is always increasing. Data seems to suggest between 8% and 12% is no-tilled, but given all the confusion over naming, we are not sure that even this is correct. We’ve heard government official talk about minimum-till, when they mean no-till and trying to explain to the same officials about strip-till, no-till and zero-till leaves you little hope of getting the right data out of any survey.

However, we know it is growing out of being a niche to being “normal”. Although we secretly think some of these no-tillers won’t like being called normal! Seeing this trend, it was very interesting to compare this to data that has just been published in the No-Till Farmer magazine from the 2017 Census of Agriculture in the US. This carried the conclusion:

“Growers are moving away from Intensive tillage in favour of no-till, min-till and cover crops.”

The number behind this certainly show we are still well behind the curve in the UK in terms of adoption.

US Tillage Practices 2017

No-Tillage 104M Acres 37%

Reduced Tillage 97M Acres 35%

Intensive Tillage 80M Acres 28%

These figures do vary considerably by state though as you would imagine with the size of the US and the climatic changes across the country. There are a number of states like Nebraska, Montana, Maryland, Delaware, Tennessee are all well over 40% and in some over 50% of acres are no-tilled. However, conservation tillage numbers are lower than this, but growing at a faster rate.

Given the information we are receiving from the government at the moment, with regards to climate and natural capital, it is likely the appetite for no-till practices will become a lot more palatable to farmers in the UK who will be pushed towards new methods of establishment. Therefore, we expect to see the UK numbers grow considerably over the next 10 years. If you are considering going no-till at the moment, we would lobe to hear from you about why you are considering a new method of establishment.

-

How To Improve Yield And Quality After Applying Your Normal Inputs?

Written by George Hepburn from QLF Agronomy

I have worked with farmers on their inputs for the last 15 years. I worked with Soil Fertility Services for 12 years as a Soil Fertility Advisor, advising many farmers on soil health and nutrition. For the last two years I have worked for QLF Agronomy (based in the US), advising farmers on the virtues of using carbon in biological and conventional farming contexts to feed the microbes and fungi which has shown significant yield, quality and fertility improvements. I am FACTs qualified and I have Certificate in Nutrition Farming from NTS. I have seen biological farming go from muck and mystery to main stream agriculture but there is still much more for us to understand about the soil and more importantly the life within it.

Whilst working with quality proven carbon-based products for the past few years I have seen the results of extensive trials and farm use to improve the crops in the US, UK and EU. I believe that future of farming is biological not chemical and over the next 10 years using carbon with inputs will become a standard procedure as the environmental factors alone, such as improved efficiencies and efficacies of fertiliser and fungicide, better conversion of residue to OM and improved breakdown of chemical residues (e.g. glyphosate) are going to push farmers and policy makers down this route. At the moment there is not enough trial work done in this area by the big agronomy companies, although it is increasing as more farmers and agronomists are switching on to the benefits of a biological system.

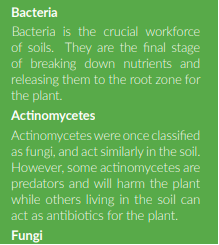

You have probably heard that there are more organisms in a teaspoon of active soil than there are people on the planet, there is a very complicated world of interactions going on beneath our feet, which even the top soil scientists admit we know little about. We do, however, know the difference that soil biology makes when it starts working for you. Soil structure improves, water is held when needed and released when not, availability of nutrients improves, it can handle traffic much better and it smells like rich dark chocolate!

One Teaspoon of Healthy Soil

• 75,000 Bacterial Species

• Metres of Fungal Hyphae

• Thousands of Protozoa

• Hundreds of Nematodes

• A Few Micro-Arthropods

• Billions of Living Creatures!!

Farmers working on direct drilling systems often notice very quickly how their soil does improve (in a soil sense of time) but many still do not look after the life in the soil enough to get the best out of it. You can now buy different strains of bacillus bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi and apply them directly to your soil, I have sold these products to farmers and they have worked sometimes but not consistently, and this is the problem there are so many variables you don’t know which ones are affecting your soil life.

I am now of the opinion that if you look after the soil, and feed it with the right foods then the soil life will follow without applying any of the actual bugs. There are certain situations that I can understand applying them for example after potatoes when large amounts of chemicals have been applied alongside a major cultivation program, but most of the time what you actually have to do to get these microbes working for you is quite simple.

Ideally you are looking for the target ratio of 45% mineral, 5% OM, 25% air and 25% water. This is the home that the microbes need to not only live but to thrive in. Microbes will respond to feeding by an increase in number, but you will never get to the optimum levels unless they have the correct surroundings. Air and water in the right ratio is key for stimulating the biology. The best way to check this is with a spade and your senses. Dig in a number of places across the field and feel at how well the spade goes in, how far the roots go down, the smell, number of earthworms (and other visible soil life) and how well residue is breaking down. If you want a point of reference go to an old hedge and dig underneath it. This is the potential of your soil.

Science can help too. Calcium and Magnesium help to define the structure of your soil. High magnesium levels can make the soil quite tight and sticky, not allowing air in and holding on to water. High calcium levels can mean the soil is too open and can’t hold on to water or nutrients. Neither of these situations are good for the soil microbes. This is where an in-depth soil test can be useful looking at the exchangeable nutrients and certain key ratios like Ca:Mg, which can guide you down a soil remediation route. When you have the correct soil structure; which I am seeing more frequently as increasing numbers of farmers do less and less tillage, the next job is to feed the soil or more importantly the microbes and fungi. FYM, compost, lime, cover crops, green manures and digestate are good ‘fertilisers’ as they are all giving the soil life a job to do, but to help them to achieve this they need some energy. Plants do with this by exuding simple sugars, fatty acids and enzymes out through the roots to feed the microbes and we can mimic this by applying similar substances to the soil.

Using a carbon-based (read sugar) product like L-CFB BOOST™ as part of your system can make a big difference, not only are there various types of sugar (sucrose, fructose, glucose and more) which is ideal for feeding the bacteria there is also a more complex food added for both microbes the fungi. Using this type of product alongside your regular applications means that every time you go through the crop you are looking after and feeding these microbes and helping them to perform their role. Do be aware that there are many types of these carbon products getting on the market going from raw beet molasses through to humic acids. Some of these are not suitable for this type of application and a lack of consistent trial data over the years puts a question mark over their benefits. Make sure you ask for independent and farm trial data and look for a good track record of results and ideally farmers that are using it that you can actually talk to.

Getting your soil microbes working for you can mean reduced inputs of fertiliser and fungicides, OM levels building, less run off and erosion, better water holding capacity, improved rooting, better residue breakdown and increased nutrient cycling. All you have to do is give them a stable home and feed them with a quality product little and often.

-

Is Organic No-Till Possible?

Written by Jerry Alford from the Soil Association

There has recently been a lot of interest in the potential of organic no-till and it has been described by some as the holy grail of organic arable farming. It is also something that is of interest to non-organic farms because of the potential to reduce inputs, particularly on less profitable break crops.

Organic arable farming systems have always been built around the use of cover crops, diverse rotations and animals. Building fertility during the rotation for high value crops and also using these covercrops and grass leys as part of weed control strategies. These regenerative phases have always been used to counter the effects of the exploitative phases where crops and tillage remove soil nutrients. Organic regulations (EU Regulations 834/2007, 889/2008 and 1235/2008) prohibit the use of artificial chemicals and fertilisers and support the minimisation of the use of non-renewable resources and off-farm inputs. Put simply, the requirement is for circular economy principles to be followed as far as possible. Many organic farms include grazing livestock enterprises and as with non-organic mixed farms, soil health will benefit. In stockless organic arable systems, clover is grown as part of the rotation and is regularly topped and mulched to build soil fertility.

It is difficult to compare an organic arable farm with a non-organic arable farm because rotations, inputs and even crops may vary. Most organic rotations include legumes because of the fertility value, but very few grow oil seed rape because of its high nutrient demand and pest risk, to both it and following crops. The inclusion of fertility building phases in the rotation is also very different, although this is becoming more widespread in nonorganic systems. Cover crops over winter as green manures are also often part of the rotation. Organic farms can use composts, manures and digestate, subject to certain restrictions, but there are no synthetic nitrogen products approved.

The biggest problem organic farmers face is weeds, particularly grass weeds. Blackgrass can be a problem but the diverse rotations including ploughing, spring cropping and low fertiliser use does seem to reduce its effects in organic systems. In non-blackgrass areas, other weed grasses like annual meadow grass and bromes can reduce yields if allowed to develop. Perennial grass weeds like couch are also a problem although an Innovative Farmers trial has shown positive effects by using buckwheat which has an allelopathic effect as well as a shading effect when the weeds are at their weakest after harvest. Ploughing has become the main weed control mechanism for many organic farmers, with seedbed preparation and cultivations being part of the weed control strategy. However, many organic farmers have looked at using min-till or non-inversion techniques through their rotations to reduce the need to plough. Most would plough 3 times during a 5-6year rotation but finding a way to grow organic crops using a no-till system during the rotation would be a good next step.

The benefits and potential of Conservation Agriculture are plain, but an organic farmer is restricted by the need to generate fertility on farm, the decision not to use chemicals and their customers choosing to buy organically certified products. The Soil Association agrees with the principles of conservation agriculture and in the long term would hope to get to a situation where tillage in organic could be reduced still further and conservation agriculture could take place with reduced or zero herbicide use. Knowing what the issue is the easy bit, finding the answer is the challenge.

So how do we get there?

If we are going to go no-till organically we need to control weeds and cover crops without chemicals. There are already three practices used worldwide, which have been tried in the UK by organic farmers, with varying degrees of success. None have been tried organically into long-term no-till situations.

The most well-known is the crimper roller. Developed by the Rodale institute in America, the ribbed roller crushes the stem of plants. The rolled plants then act as a weed controlling and moisture retaining mulch which also returns nutrients and organic matter into the soil. To work properly the crop being rolled must be an annual and at anthesis (early flowering). In America the most common crop crimped is rye which is at the correct stage when Soya and Maize are being drilled. In the UK the correct growth stage comes too late for UK cropping. The allelopathic effects of the rye may also make it unsuitable for small seeds like wheat. In an organic rotation, there is the potential to grow rye as a cover crop and then crimp and drill vetches during the fertility building phase. This second cover can then be crimped and will supply nitrogen to an autumn drilled cereal. This avoids the need to plough out a grass ley which itself can become a source of weeds.

The second technique is to drill a crop in the winter into a frost susceptible cover crop such as buck wheat, berseem clover, phacelia and mustard. This will provide a mulch to the next crop as well as nutrient recycling. Smaller seeded plants may not work in this situation because they are less competitive as seedlings, but it has been used for beans. There is a potential problem if there is a mild winter because any cover crop plants which produce seed could create a weed problem in later crops so some form of management may be necessary. Grazing with livestock could be an option because cereal and OSR plants will regrow after grazing. As part of an Innovative Farmers trial on alternatives to glyphosate a group of farmers used rollers on cover crops during a frost to investigate whether they would be an option and did show some success, which would allow late winter drilling where ground conditions allow.

A third option is to use a permanent understorey and drill into this. Similar to pasture cropping which drills into permanent pasture this form of bicropping would use a clover understorey to provide both cover and fertility to the growing crop. This technique has been used in non-organic situations where the clover is either grazed hard or sprayed with glyphosate at low rate and crops drilled into this. Clover needs soil temperatures of above 10 degrees to grow and so is not very competitive against a winter/early spring sown crop but could be an issue at harvest if the crop is not competitive. It is important to choose a smaller leaved and low growing variety of clover. Nitrogen will be released when the clover is cut and so some method of topping or crimping between rows would release nitrogen to the crop. After harvest the clover could be mulched, cut for silage or grazed prior to the field being redrilled in the autumn/winter. In theory any crop which is competitive could be drilled into this permanent cover which will self-seed and spread to maintain a competitive mulch. Possible problems come during later years if the clover grows too quickly or competes for moisture with the germinating crop plants.

Innovative Farmers are setting up a trial looking at this using white clover as a cover. To be held on long-term no-till farms and an organic farm, the plan is to plant a white clover cover crop in the summer after harvest and drill a spring crop for 2020 harvest. This can then be continued into 2021 and there is the possibly to also look at techniques to manage nitrogen release from the clover. If this proves effective it could be possible to have a rotation including cash crops every year with a permanent cover crop in the understorey.

Trying to fit these techniques into either organic or non-organic systems in the UK is tricky. Our maritime climate suits grass and weed growth, particularly during the summer and the current variable weather patterns lead to late weed flushes. If we had European type weather patterns with dry summers and hard winter frosts, it would be easier to do. As a result, we need to look at what cover crops and cash crop rotations fit best into the UK climate and farming systems. This research must also look at profitability and costs of systems as much as at inputs and this research needs to be done at both farm and regional level to move away from a one size fits all scenario. Both organic and non-organic farms would benefit from sharing this knowledge and applying those practices which they can borrow from each other or which can be adapted to fit.

Please contract the Soil Association on 0300 330 0100 for more information or advice.

-

Farmer Focus – Simon Cowell