If you would like a printed copy of any of our back issues, then they can be purchased on Farm Marketplace. You can also download the PDFs or read online from links below.

-

How To Start Drilling For £8K

Clive Bailye’s seed drill of choice is his 6m John Deere 750A , which has been used exclusively for 3-4 seasons. Last year, with an increased acreage, the founder and publisher of this Direct Driller magazine thought a second seed drill was necessary. Having just the one machine was a risk and in a difficult season would mean drilling was delayed. He looked around and found a good condition Horsch CO6 tine drill advertised in Germany.

Words and pictures by Mike Donovan

After delivery he rebuilt the coulters to a narrow profile so as to reduce soil disturbance. He says the tine drill is very useful driling after straw crops such as osr and also through the straw on second crop cereals.

Buying the drill from a German farmer was not particularly complicated, and provided him with a higher spec machine than Horsh sell in the UK. The seed dart tyres are much wider, and the machine is fitted with blockage monitors as well as full width front packers and also a liquid fert application system.

A sheaf of photos were taken, and Clive then asked for some of specific parts to show wear. The deal was done at under £5,000 which Clive says is the market value of these machines which are too large for small farmers to buy. Original owners like to buy new and sell when the machine is still in good condition.

Narrow tines with wear tiles

@Clive knew he wanted to make changes, substituting the Horsch tines and coulters for something far narrower, and has ended up getting his own design of tine made, which has a wear tile made from Ferobide, far harder than tungsten. The drill is on the farm primarily for osr and 2nd crop cereals drilled into chopped straw and the 25cm spacing is okay for these crops.

Comments on Clive’s on-line forum, TFF, said the drill many not be so good with beans, as the slot is a mere 12mm wide. And in barley the spacing may well be too wide as it needs to be thick. Clive points out that the seed pipe can actually be a bit wider than 12mm as it is in the shadow of the point. It would be good to have the option of using it for beans.

Above left: The cheap CO6 is being calibrated ready for its first outing

Above right: The adapted Horsch is being filled by the home built drill logistics trailer with seed and liquid starter fert.

Getting around the German instructions

The Horsch came, of course, with a control box and instructions in German. More on-line discussion revealed that English instructions were available on the Horsch website, and another explained that Horsch was sourcing some of these parts from Agton in Canada anyway. Zealman from New Zealand explained that the button marked with callipers should be held down for around 5 seconds. The menu is where you adjust the tramline sequence, valve layout and row numbers.

Ball hitch is a continental standard and provides a positive connection between tractor and drill

The Stocks Wizard has a rotor modified for Avadex which otherwise leaks everywhere

A Stocks Wizard is on the back of the drill and used for Avadex. Here again the knowledge of actual farmers is helpful. Alistair Nelson warned that the rotor and the surrounding shroud need to be changed, and he got good advice “from Rick at Stocks”. Clive has the same setup on the 750A and says that the Avadex leaks everywhere unless the modification is made. The drill was acquired and modified in 2016 and the results have been excellent.

The machine went through the residue without many problems and having the second drill has meant more timely planting. Clive has shown that moving into No-Till is not the expensive exercise so many farmers think it might be. The total cost, after modifications which included replacing all tines and coulters, was under £8,000.

Author Mike Donovan writes: we have featured a number of home made direct drills in @Practical Farm Ideas, and are always interested in seeing more. Please contact mike editor@farmideas.co.uk or 07778877514.

-

French Methods Of Worm Counting Compared

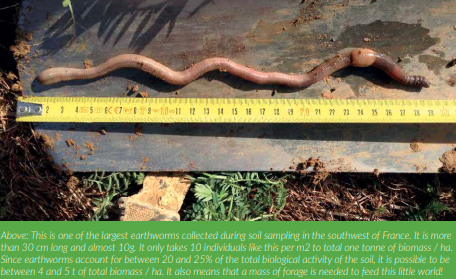

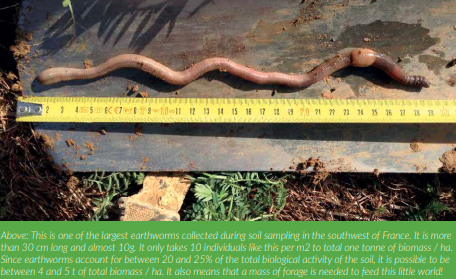

The undisputed indicator of a “healthy” soil is the earthworm. There are various methods of sampling (or extraction) in order to estimate a level of communities and analyse the different species present. But what is the best of these methods, both chemical or mechanical in nature? In this article we will discuss the methods you can use on your own farms.

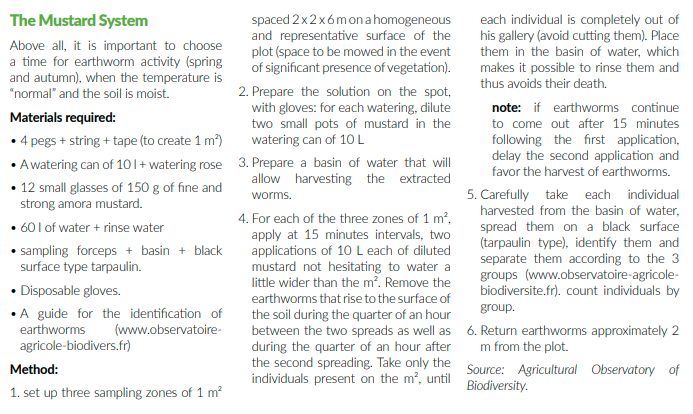

Two extraction methods are commonly used in the field: one is chemical with mustard and the other mechanical, simply using a good spade. Mustard contains an active ingredient, allyl isothiocyanate (abbreviated AITC) which has urticating properties. As soon as they feel the presence of the molecule, earthworms have only one desire: to flee! The protocol, clearly defined by the Agricultural Observatory of Biodiversity (see box insert).

The mechanical extraction consists of sampling at several different locations representative of the land parcel, a block of soil corresponding to the dimensions of the spade used, then “delicately” dissecting said block in order to account for the current earthworm community. It could not be simpler.

How Effective are these methods?

Some time ago, we interviewed a number of zero tillers about these methods. This was not a formal survey, but it has allowed us to confirm the importance of the earthworm and the need to monitor the condition of your soils according to the level of the Earthworm population present. Farmers that have tried these methods in general find them effective but are critical of the mustard method saying is more time-consuming than the spade. A question is also raised, although these two methods appear effective, do they allow us to catalogue all the individuals present? In other words: are the worms, disturbed either by the mustard or by the mechanical disturbance of the spade, not fleeing outside the sampled block?

We asked Guénola Pérès, a recognized expert on earthworms at the Agrocampus Ouest agronomy school in Rennes: “Indeed, the addition of the chemical extractant can cause them to flee; for example to push them down further into the soil, instead of bringing them up. From experience, I can say that by reflex, they flee mostly to the top, where oxygen is most present. Regardless of the method, it will always remain a possible approach and should not be assumed to be an exhaustive count of a community at a given location. We cannot achieve 100% accuracy, but we can get close to it and thus have a picture as representative as possible of a community within the soil parcel.

The sampling technique for the chemical method is important to make it possible to find all the species in a population and to have the best analysis of them. Added to this the need for three or even four repetitions of the process. The sampling surface of the mechanical method is smaller, but does risk losing efficiency compared to the chemical technique. “That’s why we have to repeat the extraction here too. With the spade, one can pick a place poor in earthworms whereas at the side, there were more.

That’s why, I advise, when doing the test with the spade, to repeat at least 5 or 6 times” (G. Pérès) Soil vibration due to penetration of the tool can also cause individuals to flee outside the sampling area. “It all depends, in fact, on the force with which the person puts in his spade and the speed with which it extracts its block,” says Guénola. “It is better to do it as quickly as possible so the strength is rather an advantage. Above all, do not “slice” your block slices because it is necessary to avoid cutting worms as much as possible. On the other hand, you really have to take the whole volume of soil: once the block is removed, if there is soil left in the hole (which often happens), you have to have a clean hole with sharp edges. Also some researchers, when using the spade, will still spread in the hole a solution of mustard, or even formalin which traps recalcitrant anecdotes.

Moist soil, Wet and Active Worm

The method depends on the soil conditions. Sampling should not be done in dry soil but in hot and sunny weather. The soil must be sufficiently warmed up. Otherwise, some of your worms will be inactive, rolled in a ball in cavities and they will not go up, even with an extractant. The chemical method is therefore ineffective when the soil is not humid enough. It is better to sample in the autumn or at the end of winter, when the soil is moist but not waterlogged.

When it’s hot, the time of day is also important. Sampling should not take place in direct sun or hot weather! Even if the mustard effect forces them to the surface, as soon as they feel the sun, the anecdics can plunge again. It is therefore advisable to take the samples at the beginning or end of the day.

Finally, G. Pérès insists: you have to know how to take your time. This too will influence the quality of the result you get. For example, if your sampling area is very full of vegetation, you should take the time to mow, also take the trouble to harvest all the worms present in the entanglements of roots. These too count! At this level, cultivation in the autumn does not make it easy for us … We will end with another question about the mustard method: why is it advisable to use the mustard brand Amora Fine and Strong? Not that the researchers are sponsored by Amora but simply because this mustard is everywhere, and it is better to use the same product to have references and make comparisons. When you use another mustard, you can get different results. Finally, the pots are then practical to store the earthworms punctually during the sampling before releasing them. Just like fishermen we identify them, we count them, we weigh them and possibly we take a picture with before releasing them! Editor’s note – although “Aroma fine and strong” maybe common in France we suggest that in the UK Colman’s mustard maybe a more consistently easy to find product!

Mustard is not the only extractant that will bring out earthworms from their galleries. there is formalin, much more effective, still used in scientific experiments but not recommended, because of its toxicity for users. Mustard, less toxic, is much easier to use; it is not expensive, and we find it everywhere. G. Peres and his students went looking for other extractants. “I had hopes for vinegar,” says the scientist. I still have some but for the moment, it’s not conclusive. In high concentrations, vinegar kills earthworms. Among all the tested products, wasabi has been quite interesting, even more effective than mustard. Wasabi, as well as being a condiment used in Japanese cuisine, it is originally a plant of the Brassicaceae family. The condiment is obtained from the stem Eutrema japonicum which is obtained as a green paste. but wasabi is not found at every street corner and it is an expensive product to extract earthworms when compared to mustard!

Mustard is not used pure. It is diluted at the rate of 300 g per 10 L of water. A good dilution is essential to the success of the method. if your mustard solution is not properly mixed, more concentrated solution pockets are formed and the method is biased. So, mix and mix again before spreading! The specialists even recommend shaking the mustard beforehand in a container with a little water like a cocktail barman might!

-

Farmer Focus – Tom Sewell

Learning from our mistakes!

One of the strangely satisfying things about farming is the opportunity we get each year to wipe the slate clean and plant a new crop into a field. Whether the previous crop had ranged from outstandingly good to outrageously bad we all get the opportunity to start again! This year I’m really looking forward to that “starting again” on more than a couple of fields. We all wish we could grow 12t/ha+ crops of wheat every year on every field (and I’m sure there is someone doing just that sitting at the bar in their local public house!) but the reality for many of us is that we have some fields that “perform” well most years and others that are just always more hard work.

The real frustration is when crops are planted in good conditions and into “good land” and then fail to deliver. That has happened on a number of our Oilseed Rape crops this year and I’m still scratching my head as to why. Strangely enough the headlands have emerged and developed well but it’s the middles of the fields in many cases where emergence and development have been frustratingly slow.

With slugs, CSFB, rabbits and pigeons this crop is starting to lose favour here with us. I guess it’s just typical, or a further development of my character, that this coincides with the year I’ve decided to invest in a low disturbance subsoiler with a small grain seeder to plant Oilseed Rape with a companion crop. (facepalm emoji would nicely sum that investment up!) Whether that ever happens now is debatable but at least we have the subsoiler for contracting and occasional soil rehabilitation where required.

On a brighter note the second wheat that for the most part of winter has just looked like stripey stubble has begun to turn green! The rows of wheat that I and my agronomist insisted were there have decided to make an appearance above the previous wheat stubble and the recent spell of warm weather combined with some early applied liquid nitrogen have seen crops move forward to a place where my ego is slightly less dented! Wheat after Oats is also pulling away nicely after a fairly slow start but the star of the show and the pictures that most often appear on my Twitter homepage are of wheat after Oilseed Rape planted straight into the regrowth.

The evenness we are seeing now after 7 autumns with the no-till approach is really encouraging. I would even say that headlands are establishing better than the middles of fields. That’s even more encouraging when your field are small! Looking forward to this spring we will be planting a larger than expected area of spring beans for ourselves and another farmer locally. We didn’t plant in the warm dry weather at the end of February as I was convinced winter wasn’t finished and the “River Fields” were bound to flood if I planted too early!

This winter has been relatively quiet and relaxing. We haven’t had many major projects to consider and other than a few meetings, shows and discussions, life has been steady. No major machinery has been changed and we are getting ready for an expected period of uncertainty given the current political situations! I’m very blessed to have farmed for the past 25 years with my Dad and this continues with only a little part time help and an occasional contractor to help out when required. But like many other father and son farming businesses there will come a time when Dad is unable to continue for whatever reason and I’ll have to either employ someone or invest in faster or wider (or both) machinery so as to cover the workload single handedly. The shortage of skilled farm labour with the ability to operate the machinery of today is a concern to me.

Perhaps collaboration with a likeminded neighbour is the way forward. Perhaps we will all be operating a fleet of robots from the comfort of our arm chair or the seat of our electric pickup?! Or perhaps, as a number of UK farmers are looking at, we will be pulling 12m notill drills and 36m sprayers with 240hp tractors and covering vast areas of land with just one man?! I’m very interested to see what’s ahead and keen to embrace the opportunities that come my way. I’m sure there will be much more learning on the way and many more mistakes made on that journey. But as someone once said “it’s better to have tried and failed than to have never tried at all” Keep trying new things, keep learning and keep advancing your farming system. Till next time!

-

Lower Pertwood Farm

Wilfred Mole writes about his farm.

Our family are the current custodians of 2600 acres of land with a chalk geology in Wiltshire, England. We took ownership of Lower Pertwood Farm in 2006 and resolved to establish an economically and ecologically sustainable organic enterprise.

As farmers we are observers. We observe the weather, the growth stage of crops, the condition of animals and the state of our bank accounts avidly. We have, however, failed, as an industry, to observe the obvious and the excuse that we did not recognise the effects of what we were doing does not wash. Our observations have been confined to a ‘need to know’ level; crops that need nitrogen, sheep that need worming or hedges that need trimming. We have patently failed to observe, or have refused to see, the red warning flag that has been waving at us for decades. Articles and statistics about declines in farmland birds, adverse effects of pesticides or losses of soil have been treated as the concern of academics or pressure groups.

This information has now coalesced to form a gigantic red flag that we can no longer fail to observe. It has advised us to change and there is a growing belief this change is imminent. It is important now that we begin to observe what is around us to provide proof of change. We do not always have to provide highly intellectual refereed papers in learned journals. The aptly termed observational study can gain recognition especially if it is part of a larger exercise. We have become a keen observer of all aspects of the farm environment and realise that, very often, these observations lead to positive outcomes.

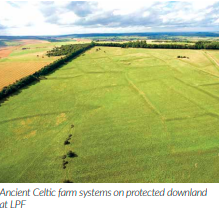

Our family are the current custodians of 2600 acres of land with a chalk geology in Wiltshire, England. This land has experienced the early efforts of the Bronze Age population, starting some 4000 years ago, to grow food for a growing population through to the zenith of the ‘chemical farming’ era of the 1970’s and 80’s. Shadows of early occupancy are prominent over a large section of the farm, overlain with modifications of Medieval origin. This land provided food, and a living, for many generations through periods of economic, political and climatic upheaval. Its soil was nurtured in order that it could maintain livestock and arable farming, whatever nature and man threw at it. Systems were developed to sustain this. In early times pare and bake, whereby thin chalky soils grew crops until the soil became exhausted, was employed.

Cropping was then abandoned and eventually livestock were grazed on reverting grasslands so that organic matter and nutrients were assimilated until cropping could begin again. A lingering memory of this practice may occur in field names Bake 1 and Bake 2. Later systems comprised rotations of grassland, fodder and arable crops as marked by field names like Sainfoin. The limits of soils suitable for cropping were well judged and were established in the name of fields, for example Starveall, which leave no doubt that this was difficult land to extract a living from. The many fields which were primarily used for grazing are memorised in having the suffix Down in the name.

Historic land management practices changed in the post-war era with the limits on soils that could be used for cropping being overcome and the necessity for livestock being reduced. Continued intensification saw inorganic fertilisers and pesticides replacing previous systems. This marked a cataclysmic landscape-scale change with the disappearance of most high quality downland, not only here but over the whole of England underlain by chalk. In addition, the character and content of the cropped area changed dramatically.

Into this changing world stepped the previous owner of Pertwood. Along with many other people a different world-view was held in which peace and love, together with everything organic, including farming, would generate happiness all around. Unfortunately for them the rest of the world did not agree and the farm, together with its entourage of alternative lifestyle people, fell on hard times. We took ownership of Lower Pertwood Farm in 2006 and resolved to establish an economically and ecologically sustainable organic enterprise. We realised that progress could be made by utilising up-to -date knowledge, technology and business acumen though this should run in tandem with tried and trusted skills and methods.

It is now over 30 years since the farm became organic and 12 since we took ownership. Those 12 years have involved a precipitous learning curve. Fortunately, we knew others gripping onto that same curve and together we have managed to maintain a forward momentum. It is gratifying that throughout this period the Organic worldwide grew steadily with the demand for our Organic Malting barley and Porridge oats expanding steadily. Prices have risen year on year and have been largely indifferent to violent global commodity price fluctuations for conventional cereals.

This is partly because the adjacent slope, of conventional farming, is rapidly becoming steeper. Perhaps it should be called the Slope of Realisation as it is coincident with an awareness that the modern agricultural revolution has come at a high price. At its most fundamental level the revolution has been paid for by the degradation of our raw material, the soil, along with numerous other ecological breakdowns which has resulted in the screws being tightened on the conventional farming business model.

The Wildlife Dividend

We have recently purchased land that has been conventionally farmed for generations and is immediately adjacent to organic system fields on Lower Pertwood Farm. This provided an opportunity to compare systems regarding an important measure of soil health, its biology. In 2018 we investigated populations of ground-dwelling invertebrates, ground beetles and spiders. Ground beetles are key indicators of change in their environment with populations that react rapidly to alterations in factors such as climate, soil cultivations, pesticide usage, cropping type etc. Levels of soil moisture have a major impact on beetle survival both directly and consequentially because of changes in the amounts of their invertebrate prey.

Prey levels depend on organisms further down the food chain, such as fungi and algae which are also affected by moisture levels. So, changes in beetle numbers reflect soil biological activity. Spiders are similarly affected by these factors. Our study certainly confirmed a difference in soil health between systems. Almost 4000 specimens were trapped, counted and identified between April and July. The organic field had three and a half times the number of beetles and twice the number of spiders than found in the conventional field.

Part of the reason for this large difference was thought to be the very dry summer weather experienced in 2018. The organic matter content of soil in the organic field was double that of the conventional field and this, together with shading provided by cover crops and weeds, aided beetle survival. Obviously any direct or longer-term chronic effects of pesticides were absent in the organic field. This exercise provided an accurate and meaningful measure of soil health. Our organic soils were more resilient to major droughting episodes and, therefore, remain more suitable for crop growth. This is an important finding if climate change predictions continue to be proved correct. These results also link into more favourable conditions for organisms further up the food chain.

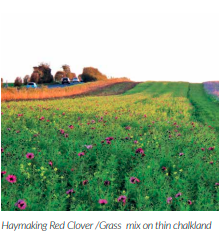

Intensive bird surveys have been conducted at the farm over the past four years with a particular focus on one typical, and now highly threatened, farmland bird. Corn bunting populations declined by 90% between 1970 and 2010 nationally and this decrease continues but diligent observations coupled with some farm management options being taken in favour of the birds has resulted in an amazing story of recovery at Lower Pertwood Farm. These birds breed in cereals and grassland then overwinter on stubble and grazed grassland. The extended provision of cereal stubbles, to help weed management, together with highly favoured leys with red clover on the farm saw an increase from 300 to 600 overwintering birds on the farm over the period 2014/15 to 2017/18. Seeds on the soil surface in stubbles and the tops of new growth in the clover/ryegrass leys provided a valuable winter food resource that enabled the winter survival of these birds.

Surveys of breeding birds, carried out in 2015 and again in 2018, recorded an increase from 132 to 235 territories, a remarkable upturn of 87% in three years. This success was promoted by the slightly later harvesting of cereal crops in the organic system compared with the increasingly earlier harvesting dates on conventional where nests are destroyed before chicks have fledged. When birds nest in grass leys cutting for silage normally takes place a week or two before fledging and, again, nests are destroyed. At Pertwood observations have determined that there is a preference for nesting in leys with red clover so those leys with white clover are cut first with red clover leys being left until chicks are observed flying. Corn bunting, along with many other farmland birds, feed their young on invertebrates and it is likely that the enhanced levels of invertebrates found in our organically farmed habitats are highly beneficial to these bird populations.

At the top of the food chain sit the birds of prey and we monitor their breeding success using nest boxes. In 2018 three broods of barn owl produced 8 young and one brood of kestrel produced five young. Interestingly, the success rate at Lower Pertwood Farm appear to have exceeded that in the surrounding locality where dry conditions have been cited as the cause of a decline. This, perhaps, again indicates that healthier, moister soils continued to supply small mammal and invertebrate food for these species on the farm whereas birds nesting on non-organic areas at other sites may have found insufficient prey to rear young.

We consider that gathering scientific evidence from the natural world to confirm that our measures are producing beneficial outcomes is crucial. We can, for a change, believe this evidence as wildlife does not have a profit motive and it does not tell lies.

The Community Dividend

Agriculture has had a bad press with farmers being judged as abusers rather than guardians of the land. Maybe some criticism is justified. Easily visible abuses, such as catastrophic episodes of hedge removal, are now being joined by major concerns regarding the state of our soils. It seems that very little that is agreeable or pleasant is seen by anyone peering over the farm gate. There is a growing perception that we are operating food factories isolated from and independent of the natural world. The path that the industry is following allows for less and less contradiction of that view. Farming must in future, operate as part of the wider ecosystem.

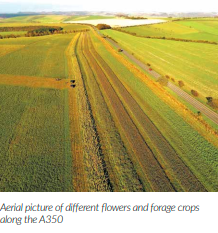

To break the bond between farming and the natural world will, logically, remove farmers from the equation to be replaced by a food production operative. For those of us following a different path it is important that we display our differences and benefits to a public who have no contact with, or knowledge of, agriculture. We have been taken aback by the reactions to a relatively straightforward and simple exercise to introduce late-summer nectar sources for invertebrates utilising colourful plants. The origins of this success lie in the use of a non-native plant, Cosmos. It grew successfully on thin, poor soils so we decided to sow a mile long strip at the edge of fields bordering the busy A350 trunk road. We added phacelia and sunflowers in one area and a field growing Sainfoin provided a colourful backdrop.

The response from the public was phenomenal with numerous congratulatory and enquiring e-mails. Observations of cars parked enabling occupants a better view of the display were frequent and instances when passers-by asked for a quick tour occurred regularly. This overwhelmingly positive reaction will be developed to educate people about organic farming. We are sure the insects would also have joined in the congratulations if they had access to bee-tea internet.com.

The Aspirational Dividend

One of the major features of Lower Pertwood Farm is its complexity. It is a kaleidoscope of land-use types ranging from large areas of gorse once use to shelter foxes and supply sport for the hunt to mature scrub ‘woodland’ which still hides Permaculture roundhouses to planted woodland, to ancient and improved grasslands to areas designated for wildlife to land on which crops are grown. Underlying this current matrix is the older one mentioned at the start of this article. Most remnants of this older matrix were significantly altered by conventional farming in the latter half of the 20th century. However, one or two fragments escaped. These occur in steep sided coombes too dangerous for tractors. The botany on parts of these coombes remains characteristic of the original, high quality chalk downland that once occupied a large portion of this site.

One of 2019s major aims will be to discover if any relict invertebrate populations have survived. This habitat type is one of the most biologically rich and diverse UK habitats and that its area declined dramatically from the mid-1960s. These remnants are potentially of great significance. To protect, enhance and, possibly, expand them would be important at a regional level. It only remains to see whether the authorities can create a regulatory environment which encourages Farmers to think more deeply about the legacy that they are leaving their children. The signs are good that this young generation have already sensed the urgent need for change.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

HOW TO PREPARE THE PERFECT SEEDBED

Leading farm machinery specialist, Sumo UK, have re-released their Mixidisc, with the Mixidisc / S, designed for high-speed stubble cultivation for preparing the perfect seedbed. Sumo, the leading British manufacturer of farm machinery, announced it would be making some design amends to the original Mixidisc, which was launched in 2016.

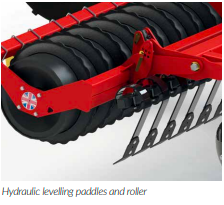

The Mixidisc / S compromises a twin row of concave discs for even contour following in the shallow cultivation systems at the front. Hydraulic levelling paddles then fill in any hollows and level out soil profile, followed by the Sumo patented Multipacka roller that creates a weather proof finish.

The company, which prides itself on building strong and powerful machinery, with the aim of improving overall farm productivity, say the New Mixidisc / S, is already out working the fields after several orders from the LAMMA 19 event at Birmingham’s NEC. “We are thrilled to see the new and improved Mixidisc / S already in the field”, says Sales Director of Sumo UK, Mark Curtis. “Our passion for min-till farming is evident in the new and improved Mixidisc / S. “The machine is designed for highspeed stubble cultivation, post-harvest, to quickly incorporate much larger volumes of crop residues, creating a micro-tilth in the soil for fast germination of volunteers and weed seeds. This results in the creation of a stale seedbed, all in just one pass, saving time and money.”

-

Burden Brothers – Total Crop Solutions

The journey of an agricultural dealership to be able to offer customers more…

At the Farm Expo Show at the Kent County Showground, we got a chance to hear from the team at Burden Brothers about the field trials they have started. George Whelan and Kris Romney were on stage talking to the farmers who attended the seminar

As a dealer they are looking to do more than just sell you machinery. They want to understand better the journey a farmer takes when looking at alternative solutions on their farm. They want to understand better how the choices farmers have in terms of the machinery they use effect the value they represent to their business. They want to work with the customer to make sure they have a good return on investment. This is a new approach from a dealer and represents their willingness to become better at advising on farm and not just be a place to sell you machinery.

To learn about the process, they decided to set up an on-farm trial. To grow a crop under several different establishment methods and take it to yield. For not just one year, hopefully for many years to come. Using all the tools at their disposal to measure and observe how the soil changes (and the changes required to the soil) over time. The key aim of the trial is to understand establishment methods and the different agronomic challenges they require and to see how they allow a farmer to tackle the issue of blackgrass on their farms.

In many ways this mirrors the journey many farmers themselves are on. Having read a guide, like the one in the last issue of Direct Driller Magazine from ADAS and learning themselves from their own farm trials. However, in this instance, the farmer has the help and support of a dealer. Sounds like the support we would all like to have!

The Trial

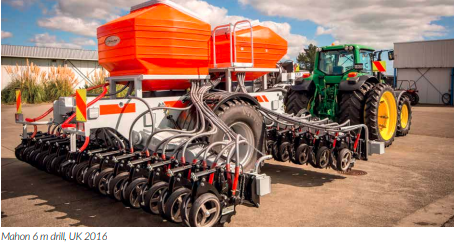

The starting point of the trial is drilling directly into pea stubble with a first wheat. Using a 750A, no-till drill, a Sumo DTS both compared to a Vaderstad Rapid pulled by a tracked Challenger (this forming the control and the existing form of establishment currently used on the farm.

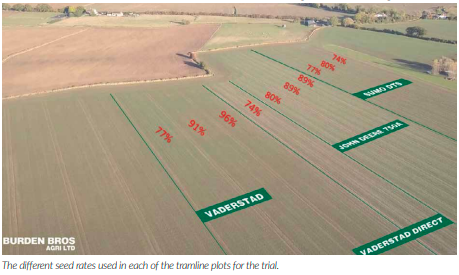

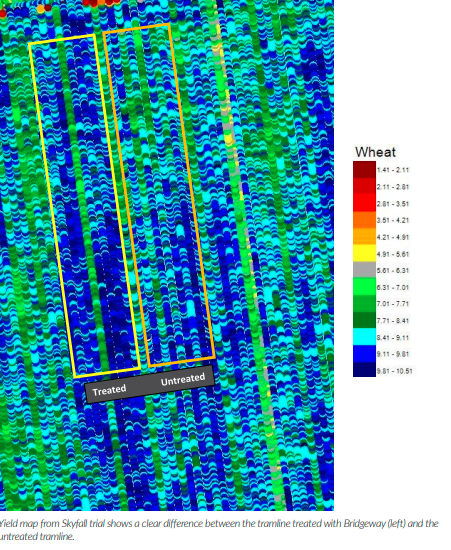

They are using a 33 hectares field, very flat field from a local famer Andrew Martin of Broadstream Farming. Down in Romney Marsh. This is an area affect by blackgrass and they are very interested in looking at different methods of blackgrass control and specifically how three different establishment techniques affect blackgrass populations. The multiple tramline plots can be seen in the picture above

As can be seen, part of the plot was cultivated and that was drilled using the Vaderstad as they would normally on the farm. The other section wasn’t cultivated and was drilled direct using the Vaderstad Rapid, the John Deere 750A and the Sumo DTS. The trial is also using different seed rates within each of the tramlines. 350,400 and 450 seeds per square metre. 350 was as close to the farm standard as possible and equated to around 175kg per hectare.

Year 1 will be wheat, Year 2 will be second wheat, Year 3 will be decided at a later date. Being a multiple year trial in such a big field this also gives Burden Brothers the options to look at agronomic changes as well.

The Initial Results

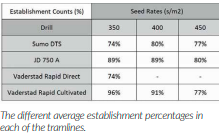

Already they have carried out establishment counts for emergence in December 2018. 6 measurements using quarter meter square counts. But because of the wider row spacing of the coulters on the DTS, this 25cm x 25cm test might not give representative results at this stage. More will be learned by further counts in the spring.

It is noticeable that the highest seed rates didn’t give best establishment, possibly due to increased competition. The results are similar (probably within a standard deviation) and therefore we will learn more as further counts are taken in the spring and then ultimately what yield each tramline produces.

At What Cost?

The next step to consider is the cost of establishment. The average establishment percentages are: 88% for the Vaderstad cultivated plots, 86% John Deere 750A plots and 77% for the Sumo DTS plots. This is where you start looking at the cost of establishing each plot. The requirements can be seen in picture 3 for each of the plots. The £58 cultivation cost per hectare only applies to the Vaderstad plot and is based on standard contractor rates. The first question is therefore, whether the increased establishment % of the Vaderstad will produce additional value over the additional cost of establishment. Something that will be able to be quantified come harvest.

They will also need to factor in the costs of the machinery required to complete the establishment (averaged over the size of a normal farm) to give a more accurate result. The AHDB have run a few webinars recently and one was on costs of establishment. It was very interesting and worth watching if you missed it. It will help you realise where your costs sit now compared to one of their monitor farms for which they have excellent sets of data. If you want to see a short video that Burden brothers have made that brings the trial more to life than just words can, you can see it by pointing the camera on your phone at the QR Code below:

What Next?

In the spring, they will move onto tiller counts, this may show better where the DTS crops have the space to grow and thrive. It will also allow Burden’s to see how these different methods effect weed control? This will be a big part of later events they hold on the farm, that you can sign up to directly with them.

Data Quality

The big part of doing any trial is having the data to back up any results. A single result doesn’t really tell you anything without lots of data points to back it up. The yield map from the last wheat crop in this field will give the starting point. The John Deere combine they will be using at harvest has yield monitoring so they will be able to create yield maps postharvest to add further statistics. The data that is backing up the trial will allow the results to be checked to see if they are statistically significant for that field. Burdens also plan to take samples from each section to determine quality of the wheat grown to quantify and difference across the plots. Next date on site is 26th June, there will be another field walk. They will have tiller and blackgrass count by then and everything will all be brought back to cost of establishment. They are very interested in not chasing the biggest yields but looking for the most profitable way of farming.

Agronomy

In year 1, the agronomy will be the same across the whole field. There are certainly options in a field this size to also look at other changes, such as using cover crops between cash crops which we often hear is an essential part of consistent and sustainable direct drilling systems. Tweaks to the timing of nitrogen applications (not changes in rates) for the direct drilled plots would also help Burden Brothers expand their knowledge around different systems and the agronomic requirements they have.

Conclusion

It is interesting that dealers are now taking the same journey to learn as farmers, doing their own trials. Working with farmers more to be able to offer better advice prior to customers looking to change systems. It’s a perfect combination for a lot of farmers, to have the ability to assess machinery before they make any decisions. To be able to make those decisions with a dealer who has spent time to learn and invest in their staff’s knowledge. This is a trial we will follow with interest to see how they get on and how it changes the way they interact with their customers.

-

2019 Biological Inoculant Trials

Clive Bailye writes …

‘Last autumn I was asked by a Hungarian company Terragro to run some tramline trials of their Biofil product.’

http://www.terragro.hu/products/The product sounds good, it is the result of 12 years of EU grant funded research and Teragro are the winners of several awards for innovation and research into bacterial strains for agricultural use. Their products have widespread EU adoption with some very positive farm and independent results over a range of crops. Only recently available in the UK it is a soil applied live product containing 7 beneficial bacterial strains it is available in acidic, normal and alkaline formulation to suit individual soil type. I’m open minded about these types of product that are becoming more commonly available its seems and believe the only way to find out if they provide benefit is to test them so I agreed to run some (unpaid) fully independent tramline trials on my own farm and also arranged to send some product to 5 other UK notill farmers.

We have set up several 1ha “tramline” trials, 2 in OSR, 3 in wheat, 2 in winter beans and 2 in spring oats all using the Biofil “normal pH” product. At this stage its far to early to speculate about any differences in crop growth but all my plots will be taken to yield quantified over the weighbridge here and results published (good or bad!). One of the other participants in the trail did send me some images of his wheat trial in Late January which look promising however.

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

CROSS SLOT NEWS

The New Zealand parent company, Cross Slot IP Ltd, is aware of continuing conjecture in the UK marketplace about the future of Cross Slot®; the only internationally recognized, patented, and proven low soil disturbance notillage technology available worldwide and represented in the UK by Primewest Limited. We are also aware of loose talk in the marketplace about Novag seed drills having authority to use the patented Cross Slot technology. Not so. Nor is it true that Novag has ever been Cross Slot’s authorised agent in any country of the world. Litigation to protect the Cross Slot patents is continuing in France in which Cross Slot is seeking substantial damages. But let there be no mistake. Things have changed significantly and rapidly with the New Zealand business, which has now transferred all of its trading to Cross Slot IP Limited; the company that has owned the IP from the outset.

We have focused on rationalizing supply and reducing the costs of manufactured openers and frames for drills and toolbars, by outsourcing this work to quality engineering companies in several countries that can offer a reliable supply of components to our high quality standards, and at internationally competitive prices. We have recently appointed a new licensee for the American continent. This licensee is already manufacturing its own machines and we have just shipped out the largest single order of openers ever supplied from New Zealand to that licensee, which has rights to about half of the world’s total no-tillage market.

This is the beginning of much bigger things for Cross Slot technologies. A separate and dedicated replacementparts operation (Cross Slot Untill Limited) has also been established to co-ordinate and manage the global sourcing and supply of parts to Cross Slot licensees, distributors, and clients. Cross Slot is also well advanced with its plans to establish a European sales, marketing, and service operation that will outsource openers and frames at competitive prices to other machinery suppliers. Cross Slot Europe Limited is to offer regional licensee opportunities and country distribution rights, and is seeking expressions of interest from parties who would like to become part of the new global Cross Slot team.

Two 10m drills manufactured in Ukraine and fitted with Cross Slot openers, were recently supplied to Russia and following a recent no-tillage conference in Kiev together with the display of a machine at Rostov-on-Don in Russia, there has been a heightened interest in Cross Slot technology from large scale farmers operating in Central and Eastern Europe. A new licensee has been appointed in New Zealand and a separate licensee is in the process of being appointed in Australia. Like all other regions, future supplies of Cross Slot machines for these countries will focus on costcompetitiveness and local client support. Primewest’s efforts in UK have been the backbone of Cross Slot availability for many years and have earned Cross Slot technology recognition as the “best in the business”. Some see it as equivalent to the “Rolls Royce” amongst seed drills. But our aim is to re-position it as the “BMW or Range Rover” of no-tillage drill technologies.

This involves establishing Cross Slot UK Limited as a standalone entity to supply machines and improve its customer support services. In short, we intend to silence the critics who have been hoping to see the eventual demise of Cross Slot altogether. Dr John Baker (baker@crossslot.com) will be speaking at Groundswell 2019, and Cross Slot will be demonstrating the technology’s superior field performance in the demonstration field, which we understand will have 10 participants. So come and see for yourself if you are in the market for a new seed drill. Further announcements can be expected with regard to Cross Slot UK Limited, its personnel and plans for the future.

Meantime, enquiries about prices and delivery of machines can be directed to Primewest, or Mr Chris Hook, the CEOdesignate of Cross Slot Europe (hook@ crossslot.com).

-

Drill Manufacturers In Focus…

NEWS FROM SLY – written by George Sly.

Sly are excited to announce that we are now UK and France Premier dealers for Precision Planting Inc, a subsidiary of Agco Corp. This opens new horizons for us in terms of technology and the ability to offer customers machines and components to significantly enhance the way they farm. The main reasons we decided to take on the dealership was through testing on our own farms of PP technology. It really unlocks many of the barriers we face in conservation agriculture. Precision Planting offer both OEM control system solutions as well as retro fit components to enhance your existing drill or planter. They have a vast engineering team based in Tremont, Illinois. The company was started by a farmer with simple retro fit components to enhance planter/drill performance, he then sold the company to Monsanto, later Monsanto sold it to Agco.

Some examples of technology we are now fitting to our own precision planters, as well as offering as retro upgrades to existing machines:

Smartfirmers:

Smartfirmers are in furrow sensors we can install on existing planters or drills. These sensors are live monitoring:

Organic Matter

CEC

Moisture

Temperature

Residue levels at drill depth

All of this information is live fed to the Precision planting 2020 monitor which stores and uploads maps to the cloud. You might ask why do we need all this information? Firstly when you take a move to conservation agriculture, certain aspects like Cover cropping, composting, no-till etc are moving you in a direction you hope is improving your soil. With this sensory technology every time you drill/ plant, you get a reading, so you can track your progress in your transition. Secondly, this technology on our machines can live adjust seed rates and fertiliser rates based on what it is seeing in the field. It can also switch seed variety/hybrid based on what it is seeing in the seed furrow. If a different variety maybe better suited to certain areas of the field the control system can switch to take seed from a separate tank. It can also control seeding depth based on moisture levels it is seeing.

Deltaforce:

I tried Deltaforce for the first time in Spring 2018 on our prototype maize planter. Deltaforce is a downforce system we can install that monitors and adjusts down pressure and load on the planter/ drill gauge/closing wheel, each row individually. It adjusts the pressure to each row unit/opener 5X per second. When planting sugar beet last spring, my field contained light silt hills and heavy clay lows, we could maintain a plant speed of 10km/h and keep depth +/- 1mm consistent. The 2020 monitor displays the KG it is placing on each row, sometimes it is negative in light soils and then positive load in heavy areas. My soil is marginal to grow precision row crops, but Deltaforce insures I can achieve even depth placement in a no-till/strip-till situation. All major European precision planters are designed for a full or mintill systems where the seedbed is very consistent and level. I am using no-till and strip till, my seedbed is not quite as even or consistent and so Deltaforce is the “key” to having uniform emergence and success.

VapplyHD:

VApplyHD is a liquid fertiliser control system using PWM technology. We monitor and control the flow on a row by row basis, we record exactly what we have delivered to each row and it is recorded on maps (which can then be compared to yield maps). The system can be spec’d as advanced or simple as the customer requires, but it is a huge leap forward in the accuracy of liquid placement for all drills and planters.

Furrowjet + Conceal – THE KEY TO RELIABLE MAIZE ESTABLISHMENT IN THE UK?

Furrowjet is a fertiliser attachment for planters, it allows us to place 3 bands of liquid, the first one is in the seeding line, the other 2 are ¾” either side of the seed furrow. For Maize this means we can place all the P+K plus some of the N requirement very close to the seed. Maize is a C4 tropical plant, we are growing it in a high latitude and to maintain and achieve reliable yield we have to get it from emergence to V5 growth stage very quickly. ALL the yield potential is set before V5 in Maize. All conventional granular planters available in the UK are generally using granular DAP in a 2”X2” system. For one, granular DAP is not as available to the plant, especially when we talk of Phosphorous, secondly, being 2X2 on one side of the seed trench it is slower to be accessed. That is time we cannot afford with our short growing season.

Conceal is a new system that we can retro fit to almost any maize planters on the market, of course it can also be specified on our planters. Conceal replaces your existing maize gauge wheel and it incorporates a liquid application knife 3” to the side of the seed trench, meaning you can place your complete N requirement for the maize plant at planting time, it is far enough from the plant not to cause any burning issues. Conceal can be fitted on one or both sides of the planter row unit.

Sly is looking forward to introducing these products to the UK, through our farm open days and farm walks the results can be seen. We welcome farmers to visit our farm and company to learn more about our products and the systems we are trying. We have 3 maize/Beet/ OSR planters being delivered this spring and plan to expand our presence in this market for the 2020 season.

Maize planters are currently available from 4 to 18 rows, in 2020 we plan to introduce central fill options for larger high output planters.

New from our Farm:

Covers drilled in November? Can it work?

One field we harvested forage maize from was supposed to come Winter Wheat, too much blackgrass was present so I decided to put it to maize again. It was early November and so drilling a cover crop would seem a waste of money and time. However I have been pleasantly surprised using Forage Turnip rape and Italian ryegrass we have had really good over winter growth and will have another 4 weeks growth until maize planting. It just shows in the right season you can still grab carbon and store nutrients with late drilled covers, something for Veg and Potato farmers to consider. It wont work every year for sure.

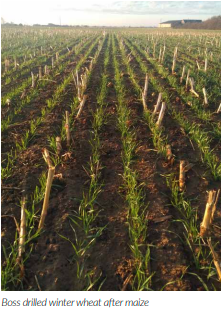

Boss drilled winter wheat after Maize

We drilled our winter wheat in late October following maize with our Sly Boss 6M drill. We also applied molasses and bacillus microbes in the furrow as a trial on around 70 hectares of Zyatt wheat. We are monitoring the difference to a untreated area. I am not expecting big visible results in one year, but we are trying to treat fields with microbes, sugars and fulvic acid over a 3-4 year period with the drill and planter (not surface applied) to monitor any changes.

Trials coming up:

We are taking 2 hectares out of production to trial vegetables and salads using strip till with interrow covers/ mulches. Much of the focus on no-till is on cereal production and we want to try and improve the efficiency of vegetable and salad production. This is after all what most of us eat every day. We will update any progress in future Direct driller issues.

-

INTRODUCTIONS

MIKE DONOVAN

Homo sapiens are hard-wired to be critical and suspicious of the unknown. We apply the maxim ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ where we can, and look for excuses to maintain the status quo. It applies to farming methods. The big gaps in no-till knowledge slow the progress of those who are direct drilling. They provide our conventional cousins the excuse to continue as they are.

It would be good to have the knowledge gaps filled and this is where this magazine is playing a huge part, and it can do this because it’s created and produced by enthusiasts who not only suck up knowledge but generate it as well. They join with similar minded farmers, and they allow all other farmers to join in. How good is that.

Looking on are those who find change difficult; advisors who are out of their comfort zone; Big-Ag which thought it could hold back the tide and continue selling bigger kit, more complex chemistry, advanced genetics; politicians and government who forget the adage about empty vessels and continue to listen to the loudest and most established voices. Enthusiasts will always focus on the unknown and what needs to be researched, and we see this in notill events. Yet it’s easy to forget just how much we do know.

Keeping soil undisturbed and covered; using plant diversity to ‘mine’ nutrients; remembering that chemicals can damage beneficial biology as well as provide protection, and how this offers huge benefits for farmers and food production. This knowledge is, and needs to be seen as fundamental. Something taught in primary school. Direct drilling has come late on the farming scene in the UK – Frank Lessiter from Brookfield, Wisconsin started his magazine No-Till Farmer back in 1972. TCS – Techniques Culturales Simplifiées – has been going 20 years under the guidance of farmer Ferderic Thomas. Direct Driller is ending its first year. Notill puts people out of their comfort zone, threatens the status quo and the livelihoods that depend on it. It continues to need mavericks at every stage, and I would really like to hear from all out there!

-

FARMER FOCUS – SIMON COWELL

I have been farming using zero-till and biological methods for fifteen years and making my own compost has always been an integral part of the system. There are lots of biological inoculants on the market but if your soil is not in a good enough condition to live and multiply, they will soon die out. On the other hand, if your soil is in the right condition, the desired microbes will most likely be there anyway.

What is unique to compost is that it is a way of applying the good biology in it’s own, perfect environment. This means that even if the soil conditions are hostile, the good biology has somewhere to live while gradually reaching out and changing the soil from a safe base.

About twenty years ago there was a general dumping area on the farm where we used to tip odd loads of horse manure, wet bales, tree cuttings and anything that wasn’t suitable to go on a bonfire but was what we now think of as compostable. Every year or so we would go and push it up with a loader bucket just to tidy up. We didn’t have a muck spreader and there wasn’t enough there to justify getting a contractor in, so it just gradually built up over about six or seven years.

In 2013 I started applying gypsum to my high magnesium soils for which my contractor used a spinning disc muck spreader. When he finished, I asked him to get rid of the old muck heap onto the heaviest part of a neighbouring field; it covered about a third of the area at roughly 6 tons/acre. The following wheat crop grew much stronger on the compost applied area and ended up yielding at least a ton to the acre more than the rest of the field.

The next crop of rape established far better in this area and grew with more vigour, going on to yield twice as much as the rest. And so, my interest in compost had begun, and I’ve been trying to replicate that amazing result ever since. Digging down, it was obvious that a massive change had taken place, the soil was a much darker colour and the structure was aggregated and open, allowing water to pass freely down to the drains. Just walking across the field, it was easy to tell where the dividing line was by the change in wetness and stickiness under foot. (Photo of rape crop) What is even more amazing is that the line still shows up in the field to this day, in spite of me of the whole field have two more compost applications since the original. (Photo of barley 12 years later)

After doing some reading up on the effects of compost, I found out that soil aggregation is created by the life in the soil, gluing particles together and leaving pore spaces between, where water and air can pass freely up and down the soil profile. The more aggregation you have, the more the air in the soil can be refreshed, and so this enhanced oxygen availability stimulates the aerobic soil life to grow and reproduce at an ever increasing rate.

Because of the relatively low application rate of compost, I soon realised that this was not a fertilisation effect but was actually a biological inoculation. I now treat compost making as a breeding operation; the original ingredients are the food which should have a carbon to nitrogen ratio equivalent to the microbes that are going to eat it, roughly 30:1, and with as many different ingredients as possible to bring a wide variety of bacteria, fungi and all soil life.

After turning manure from our own stables with a loader, which was very slow, I was lucky to find a second hand, tractor driven windrow turner for sale at a knock down price and was then able to start composting on a bigger scale. The only livestock in this area in any quantity are horses, so they are my only option as a supply of manure. There are two riding school/livery yards nearby that need to get rid of their waste and they pay a contractor to deliver it into me.

I get the trailers to tip in a straight line in the field where the compost will eventually be spread, away from ditches and drains. The line, or windrow as it is called, then needs tidying up with a loader to get it within the four meter width of the turner. Four metres is the optimum width for a turner; a wider windrow would be to big because the centre is too far from the outside and soon becomes anaerobic, and anything narrower ends up having to be miles long to contain a decent tonnage.

It is a bit of a lottery what the ingredients are from these stables, s o m e t i m e s there is a lot of wood shavings which makes it a bit high for carbon and also too dry, but I just have to cope with how ever it comes. When there is not enough moisture for the microbes to get working, I leave it over winter and then start it again in the Spring. Manure from horses bedded on straw is the best because it always seems to hold enough urine for moisture and has the right C:N ratio. When composting manure from our own stables I have more control over the ingredients and so can make it much better and biologically diverse. Local tree surgeons drop off wood chippings occasionally, a landscape maintenance company drops grass cuttings, and then there are plenty of leaves in the Autumn.

I have used gypsum on my heavy, high magnesium soils for twenty years now, but I am not sure how good it is for the soil biology, so more recently I have been adding it to the mix at the start so that it is incorporated into the compost and is applied in a biological form. Inoculation can come from a sprinkling of previously made compost, but the last batch I made had some top soil mixed in. Quite a lot of experts recommend a clay addition to give the finished product more body and give the nutrients something to hold onto, but I think the top soil is even better. It is the ultimate biological starter because it comes from a completely natural grassing marsh which grows plentiful grass without any artificial inputs; just what I want my arable fields to do.

When finished, it had the same smell as the best, the most natural soil you could ever come across, proving that the grassland biology had been multiplied by the hot aerobic process. From the first turn to being finished usually takes four or five weeks. The idea is to not let the temperature go above 70 degrees C because the useful soil life that we are trying to multiply can’t live above that. This means checking the temperature every day and turning whenever it gets to 65. The first turn breaks up everything and thoroughly mixes the carbon and nitrogen components together, causing the decomposing bacteria to go crazy, which means that if the moisture and C:N ratio are right, 70C can be reached after one day. In practice I often have to turn every day for four days, then leave a one day gap, then three days, then turn once a week until it stops heating and the temperature stabilises.

The turner is quite aggressive, which it has to be to shred all the ingredients and get a thorough mix, but this does not help fungi and larger soil life to grow and multiply, so to get the maximum diversity, it needs to be left to mature for as long as possible, preferably up to a year. The usual application rate is about four tons to the acre, which I see as just a biological inoculation. This rate is not enough to build organic matter levels, nor are there much in the way of nutrients in that amount. I can never make enough compost, so it is about getting it to cover as large an area as possible, hoping to get around the farm every four years.

This year I have tried a field at two and a half tons, which is not easy with a big ten ton spreader, but now that my no-till land is billiard table flat, my contractor doesn’t mind driving at fifteen or twenty miles per hour. Having spent the last fifteen years making and trying to perfect the art of aerobic composting, my conclusion is that there are two things that determine the quality and effectiveness of the final product: diversity and maturity. Diversity means the biggest range of different species of bacteria, fungi etc. at the start, and maturity means how long the compost has been left so that the larger arthropods, protozoa and nematodes can develop and multiply has been left so that the larger arthropods, protozoa and nematodes can develop and multiply.

-

SOIL CALCIUM AND SOIL HEALTH – THE CONNECTION?

By James Warne, Soil First Farming

I recently attended the appropriately entitled ‘Calcium Conference’ which served to remind me of the importance to distinguish between calcium and pH balance within our soils, and also the importance of calcium to the dairy cow. How easily we confuse the use of calcium has with the role of pH management within soils simply because we regularly test soil pH and then apply a calcium containing product to correct the pH.

So let me deal with this confusion. pH measures the concentration of hydrogen ions in the soil solution (when the pH is below 7) and adsorbed on the clay colloids (no mention of calcium there!) As the concentration of hydrogen ions in the soil solution rises exponentially the pH falls. For example as the pH drops from pH 6 – pH 5 the concentration of Hydrogen ions increases tenfold and if it drops from pH 6 –pH 4 the concentration of hydrogen ions increases by 100. To neutralise the hydrogen ions we most usually apply lime, or calcium carbonate in its various forms. The neutralising bit here is the carbonate, NOT the calcium. The carbonate disassociates from the calcium in the soil and reacts with the hydrogen to leave carbon dioxide and water while the calcium ion replaces the hydrogen in the soil solution and on the clay colloids. To get scientific for a moment the reaction is

CaCO3 + H2 -> Ca2+ + CO2 + H20

Calcium carbonate in the soil reacts with the hydrogen ions (the acidity) to give calcium ions, carbon dioxide and water. So if the calcium does not neutralise the acidity why should I be worried about my soil calcium levels? Calcium is the sixth most abundant element in plants, and animals for that matter.

It is also the third most abundant metal in the earth’s crust. Historically it has always been assumed that there is generally enough calcium in the soil to supply the crop requirements if the soil is limed to the correct pH. However we also loose calcium from the soil in large amounts every year by a variety of processes. Crop removal via mechanical or animal means removes varying amounts of calcium but these losses is quite small compared to losses caused by inorganic fertilisers and natural leaching.

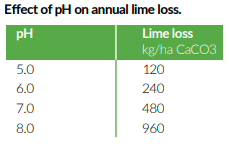

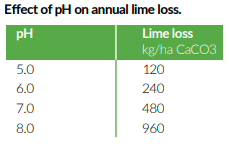

Work done at Rothamsted has shown that considerable amounts of calcium are lost by leaching, and the amounts lost by leaching double with every unit increase in pH, see the table below.

Similarly calcium can be lost by the use of fertilisers, but why is this? Most inorganic fertilisers are based around sulphates, nitrates or chlorides which are negatively charged anions when disassociated in the soil. They tend to combine with dominant cation calcium in the soil and leach readily in the soil solution. Again work done at Rothamsted suggests that every kg of N as urea and ammonium nitrate needs to be balanced with 2-3 kgs of CaCO3.

Further work needs to be done to establish an ideal model for calcium losses but it is probably somewhere in the region of 50 – 100kg per hectare per year depending upon soil type, drainage etc. You cannot rely on the soil pH to be an indicator of satisfactory soil calcium, the two do not correlate well enough for these days of precision agriculture. I have lost count of the number of times I have heard the following phrase. “I haven’t limed for several years, each time we check the soil pH the results show we don’t need to lime”. But when a cation exchange analysis is undertaken the soil can be very low in calcium. Other factors are keeping the pH at a satisfactory level, which are detrimental to yield and soil health.

So why is calcium so important within the soil?

Firstly as mentioned above calcium is the dominant cation within the soil and as such plays an important role in soil aggregation due to the way its ionic charge, size and hydration acts upon the clay colloids. Soil aggregation or flocculation is the process by which soil colloids and organic matter clump together to form aggregates. It is these aggregates, or crumb structure, which we call tilth. It is this aggregation of the soil that creates pore space within the soil and consequently it is the pore space which allows water and air to move through the soil. As we all seem to be preoccupied with ‘soil health’ at present I always feel that calcium is a good starting point as it drives so many of the other factors which contribute to soil health.

Calcium is essential too for the soil biology (another function of soil health) The beneficial soil biology are generally aerobic (i.e. they need oxygen to function). It is the porosity created as described above by the calcium that allows the movement of oxygen to allow the biology to flourish. Equally the biology also requires large amounts of calcium to support their bodily functions.

Calcium within the plant..

All plants require calcium, it is an essential nutrient along with nitrogen, phosphate, copper etc etc. In fact it is the sixth most important element by concentration within plant tissues. Calcium uptake maybe affected by the presence of other cations in the soil such as potassium, magnesium, ammonium etc. Similarly though excess calcium may reduce the uptake of these cations too, so it’s not simply a case of over applying in the hope that it may do some good. Excess soil calcium can cause as much trouble as deficiency.

Calcium is mainly taken up with the soil water and moves within the xylem stream. Consequently when the transpiration rate is reduced calcium intake may suffer. Parts of the plant with a low transpiration rate may also be low in calcium such as the fruits. Once used within the plant calcium is reasonably immobile, consequently crops require a continuous availability of calcium. Calcium is an important element within the cell wall structure where it forms calcium pectate which give stability and bind cell walls together.

Calcium pectate give the cells walls their structure and strength and gives the plant its standing strength and a higher resistance to fungal infections and aphid borne virus. Many fungi and bacteria secrete enzymes which impair cell wall integrity, calcium can help to reduce this effect. Calcium also plays an important part in fruit quality and starch formation amongst other functions. Being immobile deficiency symptoms show in the younger leaves and plant issues first. Typical symptoms are stunting of plants and lack of leaf expansion.

Useful forms of calcium

In agriculture terms we really only use three forms of calcium containing product, lime, chalk or gypsum. Lime can be further divided into calcitic or dolomitic lime. Calcitic lime contains calcium carbonate, as will chalk, while dolomitic contains calcium and magnesium carbonate. Gypsum contains calcium sulphate. All of these products are crushed and ground from rock and consequently the quality can be very variable depending upon the source. To enable these products to work effectively they need to be very finely ground to dust.

Otherwise the release of calcium cannot be predicted. Dust is particularly difficult to spread accurately unless it is formed into a prill. Calcium carbonate also has a low solubility compared with gypsum, therefore the calcium will be much more readily available from the gypsum compared to the lime. Another overlooked source is CAN, once a widely used fertiliser, but now consigned to horticultural crops it is a useful source of calcium plus the ammonium nutrition which is altogether better for crop health than nitrate.

Finally…

In conclusion, if you are trying to build a healthy soil and grow a healthy crop, calcium should be your first consideration, and just because your pH is correct don’t assume you have the correct level of calcium for your soil. And finally, I don’t sell calcium products but most soil tests I receive do suggest that our soils are in need of calcium.

References

Principles of Plant Nutrition 2001. Mengel

& Kirkby

Crop Nutrition & Fertiliser Use 1996.

Archer -

DRILL MANUFACTURERS IN FOCUS…

New drill & mobile app developments from John Deere

John Deere latest drill and mobile app developments are both designed to improve machine efficiency and productivity at lower operating costs. The new ProSeries opener for the 750A All-Till drill will be available from January 2019 and can be retrofitted to existing machines. This replaces the 90 Series opener that has been a feature of the drill since its introduction in the mid1990s, with global sales of well over two million units.

A key benefit of the 750A is the extremely low soil disturbance created at the point of drilling, which fits well with cultural methods for controlling grass weeds, particularly blackgrass. The new opener is designed to provide even less soil disturbance, more consistent seeding depth, better seed to soil contact and improved slot closure for more even crop emergence and potentially higher yields. It also features only one grease point and increased wear life to minimise annual maintenance costs.

In addition for 2019, John Deere will have new, fully ISOBUS compliant software available for both the 750A AllTill and 740A Min-Till drills, which works with both John Deere and third party displays. As well as managing features such as section control, the software prevents overdosing in tramlines and provides a predosing function that prevents gaps in the field when setting off from a standing start.

Equipment logistics, efficiency and productivity can all be improved by John Deere’s new MyOperations app, which allows users to see machine and field data remotely from their mobile phone or tablet and receive alerts on the go. This free app means farmers and contractors can experience less downtime as well as reduce operating costs, by always knowing where machines are and what they are doing.

The personalised Operations Centre in MyJohnDeere.com can also be used anywhere and at any time to reference both historic field operation information and current data coming off the field. This is managed under the key headings harvest, seeding, application and tillage. The app has been available initially to new S700 Series combine owners for the 2018 harvest season, to make initial combine optimisation even easier. This option enables users to remotely view and change several combine settings to optimise grain quality and cleanliness of the sample, and minimise losses; the operator then just has to confirm the adjustments on the in-cab display. This allows maximum performance and quality to be consistently achieved, even while harvesting conditions are changing.

Use of the MyOperations app requires an online John Deere Operations Centre account connected to a machine’s JDLink telematics system. It is suitable for use with any internet connected smartphone equipped with iOS system 10.0 or Android system 4.4 or later. After downloading the free app from the Apple App or Google Play stores, customers need to log into their existing account or register a new account at www.MyJohnDeere. com. JDLink connects the machine to the customer’s account and with a suitable in-cab display, field operation and documentation data is available for analysis.

Some additional features are necessary for use of the app with the S700 Series combine settings function. Information available within the app includes location history, which shows where all machines in a business have driven on that day, a wide range of machine measurements including engine utilisation and fuel levels, field maps and productivity data including areas worked, and annual crop summaries. Remote Display Access (RDA) is available within the app to support operators in the field. In addition, MyOperations users can view machine notifications such as geofence and curfew alerts, low fuel, file management and machine maintenance and diagnostic codes. Users can also edit preferences to receive prioritised alerts and notifications, so that field operations and logistics can be managed more quickly and efficiently.

-

Farmerama: Innovative Ideas For Today’s Farmer

By Olivia Oldham, Farmerama

Do you learn the most talking to other farmers? Don’t always find the time to get out there and hear what’s going on? Well that’s what we are here for.

I am part of Farmerama Radio, an award-winning podcast released once a month sharing the voices of farmers in the UK and around the world. Farmerama is committed to positive ecological futures for the earth and its people, and we believe that the farmers of the world will determine this. Each month we feature recordings of farmers in the UK and further afield, focused on practical tips, innovative ideas and the nitty-gritty of farming today.

We are sharing knowledge of what really works in the field and for farming businesses, from farmer to farmer. Every episode includes three to four different short stories that we weave together. Here we will give you a taster of four stories from four different episodes to whet your appetite. We definitely encourage you to give the episodes a listen because there is lots more to learn than what we cover here, plus it’s always better to hear it from the farmer’s mouth!

You can find the show online at www. soundcloud.com/farmerama-radio/ or farmerama.co, or if you already listen to podcasts then it’s accessible on any podcasting service, just search for Farmerama. Here we go…

Episode 36: Cowpat Lover Greg Judy at Groundswell Conference

In episode 36, we spoke with Greg Judy, a mob grazer based in Missouri, about how mob grazing provides a triplewin by improving soil health, grassland biodiversity, and farm profitability, all with the goal of increasing the longterm viability of a farm. And all this can be achieved even with limited resources. Mob grazing involves putting larger numbers of animals onto smaller areas of land, and moving them around daily, as opposed to giving them access to the whole field continuously.

The mob grazing approach affects the biology, chemistry and physics of the soil. Biologically, it allows different grasses, the seeds of which are already in the soil, to germinate and come up. Mob grazing is also far more effective than continuous grazing at spreading manure across a piece of land. For example, Greg told us that on a farm of 100 acres, it would take 27 years under a continuous grazing management strategy to cover the whole farm with cowpats. With mob grazing, though, the same coverage could be achieved in only one and a half years. This manure coverage improves the chemical and physical composition of the soil by providing extremely good fertilization and creating a better environment for worms.

None of this matters, though, if the farm enterprise isn’t sustainable. Using the cattle’s (or other livestock’s) own natural waste reduces the need for fertiliser inputs, while using livestock to increase the variety of grasses in the pasture reduces the need to buy grass seed, for example. By moving the animals every day and keeping them away from their manure and urine, they are also kept away from the flies which are attracted to fresh waste. This is a simple and free way of keeping animals healthy and reducing the incidence of problems like worms. So, Greg says, “one of the best investments to make to improve farm profitability is in water infrastructure and fencing to be able to implement mob grazing”.

Speaking of sustainability, Greg emphasised that more than being sustainable, we should be aiming to be regenerative. If we come onto land that has been degraded by unsustainable practices in the past, we don’t want to ‘sustain’ it at its existing levels – we want to regenerate it and make it better for future generations. Mob grazing is one way to do this, using animals to restore soil health. An extended interview with Greg can also be found in this month’s short.

Episode 35: California Paying Farmers to Sequester Carbon with Charles Schembre

In episode 35, we learned about California’s Healthy Soils Program, a scheme which compensates farmers for increasing their soil health – with the goal of sequestering carbon and increasing water retention. For example, one farm is being paid USD50,000 to sequester 345.6 tonnes of greenhouse gases per year. They plan to do this by transitioning to a minimum-tillage approach, planting multi-species legume cover crops, and spreading compost across 70 acres. The quantities sequestered under the scheme are estimated using CARB GHG [carb G-H-G] Quantification Methodology and tools.