As I embarked on my Nuffield scholarship in 2022, I held soil carbon markets (SCMs) in very high regard. The media buzz portrayed them as a transformative solution for promoting regenerative farming in UK agriculture. Sceptics of SCMs were dismissed as ‘killjoys’ and those likening it to the ‘wild west’ considered ‘spoilsports’.

Soil carbon dynamics

Understanding the dynamics of soil carbon (C) sequestration was essential at the start of my Nuffield. Researchers in France and the US have clarified that soil continuously loses carbon, at between 1 and 5% loss of background soil organic matter (SOM) annually. Soil micro-organisms, together with larger fauna (e.g. earthworms), break down the SOM, using its organic carbon as a food source and respiring it to the atmosphere as CO2. This loss is usually greater than C inputs in crop stubble, chaff and roots; therefore to maintain or increase soil carbon levels, farmers need to apply additional carbon inputs through cover crop residues, straw returned, manure or inclusion of grass leys in the rotation. Think of your soil carbon balance like a bank account- if your deposits are larger than your withdrawals then your balance is going to increase, and vice versa.

The soil micro-organisms process these fresh carbon additions, eventually releasing 90% of the carbon back to the atmosphere as respirational CO2. Around half of this loss may occur in the first year, three quarters loss by 4 years with the remainder being lost over the next 10 years or so. Only 10% may remain as stable persistent soil carbon which has potential for climate change mitigation and relevant for offsetting. This 10% is the excrement or dead bodies (aka necromass) of those micro-organisms. In summary, sequestering soil carbon is quite hard! Soil micro-organisms prefer to cycle soil carbon rather than just let you store it, in the process they provide the vital soil health and function farmers rely on.

The complexity of sequestering soil carbon becomes apparent here. When bold claims are made about significant increases in total soil carbon, it’s crucial to discern whether this carbon is part of the transient 90% or the more stable 10%. Selling the temporary 90% as carbon credits is misleading, as this carbon quite quickly returns to the atmosphere. As one farmer recently explained to me, selling this 90% fraction as offsets could be likened to fly tipping- collecting someone else’s rubbish but then throwing empty cans out the window as they drive down the road. I was rather impressed with their analogy!

In the case of a move towards minimal or no-till, has the farmer just re-distributed carbon within the soil profile, concentrating it in the surface? If I tidy my house and move all the downstairs clutter upstairs, the bottom floor may look tidier while the upper floor may look twice as cluttered. But the total amount of clutter hasn’t changed, I’ve just concentrated it upstairs- it works the same for your soil carbon.

Information asymmetry

When selling any product, thorough product knowledge is key. It allows you to help the buyer discern if your product matches their needs and expectations, and explain any potential risks and benefits over possible alternatives. In SCMs information asymmetry between market participants can create power imbalances, inefficiencies and moral hazard. Are farmers and buyers fully aware of the credibility issues and potential risks of trading carbon credits? Are carbon brokers being open and honest about this? It seems many do not grasp the intricacies of what they are trading. If you think you’re selling a horse and the buyer later discovers you sold them a donkey- they are not going to be happy about that, even if you didn’t know at the time! I think it’s vital for farmers, buyers and carbon brokers to upskill themselves on the SCM so they know what questions to be asking of each other, to avoid potential hazards.

The importance of Additionality

The carbon offset market exists solely to mitigate climate change by neutralizing new emissions and storing them in sinks like soil. For offsets to be genuine, additionality is crucial- the sale of carbon credits must drive new carbon removal activities. If these activities would occur regardless, the credits don’t deliver their intended benefit to the climate.

Let’s imagine you lead a healthy lifestyle- you eat healthily, and you normally attend two gym sessions per week. But today you decide to eat a slice of cake. It’s all good- you’ll cancel out the cake when you attend your second weekly gym session tomorrow. No you won’t. You already do two gym sessions per week, to truly cancel out the slice of cake you would need to attend an additional 3rd gym session- otherwise you’re just going to put on weight! It’s the same with carbon offsets that demonstrate poor additionality- companies can’t genuinely offset carbon emissions with an activity that was already happening or going to happen anyway. To do so would be to brush their climate responsibilities aside, because they would continue emitting without having genuinely neutralised them elsewhere, their emissions would continue to warm the climate.

During my research, I found that early adopters of regenerative practices were the main participants in SCMs. These farmers had already implemented most of their carbon farming practices in the past, raising questions about the additionality of these credits. Buyers of these credits would be claiming credit for routine actions that would have occurred anyway—effectively greenwashing. This is akin to you using your 2nd routine weekly gym session to offset that piece of cake you ate. Clearly, without additionality carbon credits don’t accelerate the adoption of regenerative farming- they maintain the status quo, and they don’t deliver their intended benefit to the climate- defying the sole reason they were created in the first place. In the absence of it driving either of those things one has to ask what the point of them is?

Additionality rules seem to be the achilleas heel for these carbon brokers. If they stick to the rules too rigidly they likely don’t have a business. At today’s low carbon prices, undoubtedly the path of least resistance for them is to use these early adopting regenerative farmers to generate carbon credits- they’re already doing these farming practices so arguably don’t need any incentive to carry on doing so. So even small incentives will be attractive to them- after all they don’t have to do anything different. Only if the carbon price increases significantly could incentives be large enough to persuade conventional farmers to change their ways- which would improve additionality.

The strict (but necessary) additionality requirement for offsets creates a potential injustice for early adopting regenerative farmers who feel they should be rewarded for their early efforts. While I agree rewarding early adopters matters, offsets seem an improper mechanism with which to do so.

Insetting: a Viable alternative?

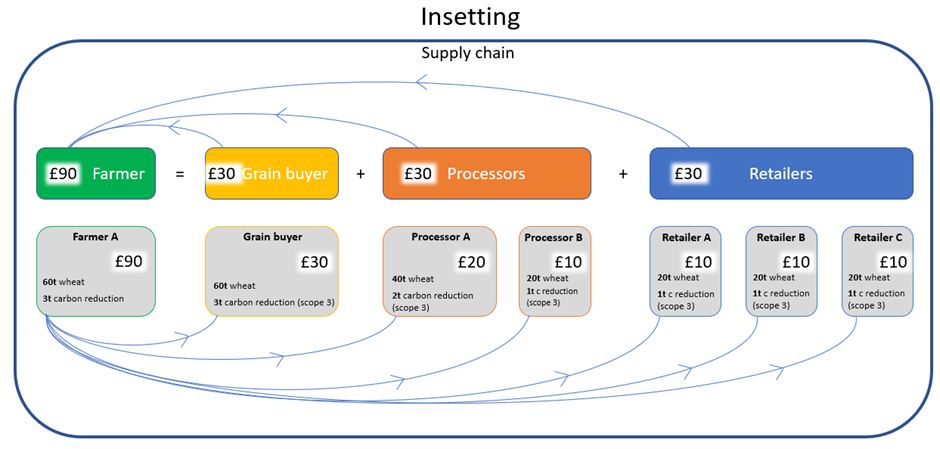

Insetting, where companies work with farmers to reduce ‘scope 3’ emissions (emissions associated with the production of their raw materials such as grain or milk) within their supply chain, offers a promising alternative. Unlike offsetting, insetting keeps carbon credits within the value chain, reducing issues related to additionality and permanence. It allows companies to reward both early and late adopters, making it more attractive to early adopting farmers who feel excluded from SCMs.

Insetting has additional benefits. When a farmer reduces net emissions, all stakeholders in the supply chain can claim this ‘scope 3’ reduction, fostering potential collaboration and cost sharing. At this point I can almost hear farmers shouting ‘but I get fleeced by my supply chain!’. For insetting to be fair and effective, policy and regulation might well be necessary to ensure food and beverage companies collaborate justly with farmers. But farmers shouldn’t consider themselves helpless- you don’t have to wait around for your commodity buyer to play catch up or play fair. You can be proactive, go out and find new customers that want to buy low carbon or regeneratively grown commodities, if that’s what you want to do- those customers are out there and will likely pay a premium.

A role for policy and legislation?

In the US, the ’45Z’ tax credit policy incentivises renewable fuel producers to source low-carbon corn from early adopting regenerative farmers, an example of insetting. This model rewards early adopters which motivates others to follow suit, driving sector-wide change. Unlike the SCM, which often excludes early adopters, this approach channels financial incentives to those already practicing sustainable farming- without any issues with additionality.

Conclusion

You may be reading this thinking I’ve joined the ‘killjoys’ of the carbon offset market. I haven’t. While I still support carbon offsetting in principle, it must be genuine and effective. Current SCMs seem to maintain the status quo rather than drive meaningful change, and therefore aren’t delivering their intended benefits for the climate. If carbon prices rise sufficiently, SCMs might incentivise new practices, meeting additionality requirements and genuine climate mitigation, whilst delivering a myriad of wider benefits to farmers and the environment. What’s not to like about that (if it happens!). However, this could also exclude early adopters due to strict (but necessary) additionality rules, who could be perversely incentivised to un-do past practices in order to participate- another reason why the insetting model may be seen as superior.

Climate change poses significant risks to us, future generations and especially the agricultural sector, making it vital to avoid greenwashing. For farmers to get embroiled in greenwash would only be shooting themselves in the foot.

Farmers face numerous challenges, including rising costs, climate change, and environmental regulations- it’s necessary for farmers to spearhead internal change of the sector to combat these challenges. The jury is out as to whether the SCM has a relevant role to play here, in the meantime promoting the adoption of regenerative practices for reasons beyond small financial incentives from SCMs might be more effective. There is ample support available through schemes like the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) and water companies to support farmers’ transitions.

Do we need SCMs? What is their purpose if not to deliver their intended benefits? Do they present more risk or opportunity? These questions are crucial as we navigate the future of UK agriculture. For further insights, my full Nuffield report is available here.

Find Ben on X/Twitter: @soilcarBEN