First published in @Practical Farm Ideas Issue #95, Issue 24-3 Autumn 2015

No-till, zero-till and conservation agriculture have subtle differences in meaning. In all of them, seeds are sown directly into the stubble and trash (or rather mulch) left by the combine. Each of these terms is there to reflect the standpoint of the user. Zero-till says “I never use any cultivation”, while No-Till is fractionally softer, so if a very light run over with a cultivator set at a few millimeters looks necessary, it will be done. The problem is that No-Till can then become ‘lighttill’ which can then damage the natural soil structure which the system relies on, as well as reducing and removing the surface trash or mulch which is such a vital part of the system. Conservation agriculture has an even wider meaning. Cornell University has the best description: ‘CA is a set of soil management practices that minimize the disruption of the soil’s structure, composition and natural biodiversity.

Despite high variability in the types of crops grown and specific management regimes, all forms of conservation agriculture share three core principles. These include: A. maintenance of permanent or semi-permanent soil cover (using either a previous crop residue or specifically growing a cover crop for this purpose); B. minimum soil disturbance through tillage (just enough to get the seed into the ground); C. regular crop rotations to help combat the various biotic constraints. CA also uses or promotes where possible or needed various management practices listed below: 1. utilisation of green manures/ cover crops (GMCC’s) to produce the residue cover; 2. no burning of crop residues; 3. integrated disease and pest management; 4. controlled/limited human and mechanical traffic over agricultural soils.

Tony Reynolds and grandson Sam who is studying at Moulton Coll and is fully engaged on the farm, cropping methods and soil biology

Why the right terminology is necessary The UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO) is even less definite: Conservation Agriculture (CA) is an approach to managing agro-ecosystems for improved and sustained productivity, increased profits and food security while preserving and enhancing the resource base and the environment. CA is characterised by three linked principles, namely: 1. Continuous minimum mechanical soil disturbance. 2. Permanent organic soil cover. 3. Diversification of crop

species grown in sequences and/or associations. Britain’s farming ministry, DEFRA, has yet to connect with the phrase, favouring Sustainable Agriculture instead. If DEFRA is luke-warm, there’s a growing army of UK farmers who are keen, committed and hugely knowledgeable, and some of these are happy to impart what they know. Regular readers of this Soil+ section in PFI will have read reports on some of these, and it is true that the knowledge of these farmers exceeds that of other experts.

Zero-till has given a decade of great farming

Tony Reynolds is one of the great UK ‘daddies’ of zero-till and conservation agriculture. Over the last five years I have listened to his contribution to various conferences, sometimes have managed to share a cuppa afterwards, and have always wanted to get to see and report on his farm. This season the stars lined up and I arrived at Thurlby Grange Farm near Bourne, Lincs on an afternoon which had followed some heavy morning rain. Arable farms run on zero-tillage are never impressive. The yards and buildings are largely empty of machinery – there’s no big power around.

The normal range of ploughs, cultivators, harrows, one-pass kit, tracks and large diesel tanks are just absent. So one searches in vain for signs of life, the wheels and machinery that provide the conventional energy to an arable farm. With zero-till, buildings are eerily vacant. The only machinery seems fairly modest in size, and it can give the initial impression that you’ve come to wrong farm, to a farm which does little or no work itself but leaves it all to contractors or FBT tenants.

“Wouldn’t it be better to keep this top soil on your own farm”

It was October, and the land wet, and ditches three-quarters full of brown water, as was the norm when the ADAS advisor walked the land, and came out with the question: “Wouldn’t it be better to keep this top soil on your own farm?” The question struck a chord. The farm had been in the family for generations and one of Tony’s primarily goals is to leave it in good fettle for the next. Every farmer has relatively few farming seasons and Tony had seen a gradual deterioration in soil quality as well as erosion from water and wind. Losing soil was a poor way to go about providing a legacy, and he also reasoned it was a poor way to farm as well.

The question lodged in his mind, and while no big decisions were taken immediately the next spring he did no cultivations for some beans and spring barley, and for the next two years learned what he could about no-tilling.

“We tried a few different drills notilling 100 acres in one place and 200 somewhere else. Learning was not simple. Advisors in farming have always been risk averse, and colleges even more so. The farming internet was in its infancy, so contact with others more knowledgeable and interested in farming with zero-till was just not possible.” Some direct drill salesmen had experience form overseas, but to a large extent Tony was on his own. But the ADAS advisor gave another useful piece of advice “either plough it or don’t touch it.”

In 2003, after two years of experimentation, they had a farm meeting to decide whether or not to commit the farm business to zero-till. Tony’s son-inlaw Clive was already a key figure in the business and he, together with daughter Terry and others were in full agreement to make the change.

The damage of top tillage

Tony is emphatic that merely reducing soil tillage rather than eliminating it does more harm than good. Soil pores are sealed by the the finer soil particles in the disturbed stratum and consequently water infiltration is reduced, root growth is restricted and yields suffer.

Above: The quality of zero-till soil is easy to see, and smell. It provides field crops with a rooting compound that’s more horticultural than agricultural

Maintaining stubble provides drainage structure, an environment for worms and other soil creatures which improve soil condition. Roots and stubble anchor soil.

When sowing into the previous crop’s stubble, the RTK (Real Time Kinematic) global navigation satellite system now available on the farms means that the second crop (e.g. beans) can be sown precisely between the wheat stubble rows.

The system can also be used to relay drill cover crops between the lines of the growing main crop. OSR is broadcast directly, together with slug pellets if needed, by the Autocast which comprises a seed hopper attached behind the combine header; a fan and a manifold distribute seed to spreading plates and a land wheel meters the seed.

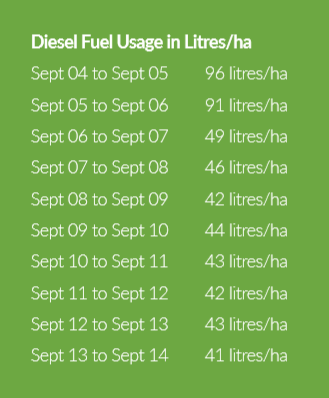

The combine used on the farm has a Shelbourne Reynolds stripper header which leaves stubble standing in the field. This speeds up combining and leaves an ideal environment for the subsequent crop (and for trapping incoming windblown soil). Crop establishment costs: Tony made a broad-brush estimate that CA crop production costs are around £30/ha compared with £266/ha for conventionally tilled crops. Some of this saving is due to lower fuel bills as diesel consumption, and the table shows the fuel use per ha since 2004-5, after zerotilling had been introduced.

Crop yields: It is to be expected that soils damaged by conventional tillage will need time to heal and re-establish their natural structure of aggregates, pores and channels; and this has been Tony’s experience. Yields in year one after adopting CA were not noticeably lower, however years two to five may show a dip until pre-switch levels were re-achieved in year 6. From then on yields continued to rise before stabilising in year eight at a level higher than year zero. Tony continues to investigate why this yield dip in years 2 to 5 occurs on some soils but not others.

Earthworms are crucial to the soil rehabilitation process and their numbers quickly rise under a no-till and residue retention regime (Figure 6). Tony has made some measurements and he found 47 earthworms in one sample of his notill soil, whereas his neighbour, on the other side of the fence and with the same soil but ploughed each cropping season, had only one worm in the same volume of soil. The average worm count on the farm is between 80 and 90 under an area of 1m2, the aim is to achieve 140-150/ m2.

Soil Carbon Levels: During the soil recuperation process, and beyond, soil carbon levels have continued to rise. The soil organic carbon (SOC) levels were measured by the Uni of Reading as:

2003 – 2.1% (low)

2007 – 4.6% (good)

2014 – 6.3% (v good)

SOC indicates soil fertility and so levels of P and K application have fallen by 80% each and N by 50% over the same period.

The effects on the two big arable problems

Blackgrass: one of the most difficult and costly problems of arable farms in the UK. Tony explained how a no- till regime can reduce its incidence. Eighty percent of blackgrass seeds die in the

soil in year one and so, if there is no soil inversion, the mortality rate in year two will be eighty percent of the remaining twenty percent. No-till in conjunction with judicious application of Atlantis (iodosulfuro+mesosulfuron) at 0.4kg/ha has controlled blackgrass on the farm.

GPS mapping is used throughout the farms for soil fertility and crop yields. It is also useful for mapping patches of troublesome weeds so that they can be dealt with selectively, rather than overdosing areas with no weed problems.

Slugs: Zero-till helps to control slugs in a number of ways. Slugs need a diet of rotting material and so seedlings growing in soil with low organic matter have no alternative feed for the slugs. In addition, worms like to eat slug eggs, so a high worm population helps, and the same is true for ground beetles, which

Wheat drilled on Sept 17 looks on the way to doing well

need a greater number of eggs. There’s a balance created naturally, rather than a dependence on pelleting.

The benefits of good record keeping

Readers have to thank Tony for his consistent record keeping over the seasons which both preceded and followed the change to zero-till. The numbers provide evidence like nothing else.

The experience which others had suggested that the conversion of the farm might take six years, and there was an obvious need to reduce the financial impact of this, and so they developed a six year plans for light, medium and heavy soils. In the first years of no cultivation the soil, low in organic matter and with few worms, bacteria and so on, will show poorer than normal fertility. So to counteract this they increased both seed and fertiliser rates to bridge the gap between soils being conditioned mechanically and then being conditioned with natural processes using surface mulch, worms etc. Fig 1. shows the changes they planned and enacted starting in 2003.

Seed Drills

With 2,000ha to drill on three separate farms there’s a chance to have different drills working at the same time. This season the home farm with 500 acres had a new Weaving GD 4800T which works on 24m tramlines and is pulled with a Case 140hp, and a similar 6m drilled 860ha on another farm for 30m tramlines. “The Weaving is the biggest advance in conservation agriculture for the past three generations.” He says the sharply angled double disc opener works very effectively, and cuts through straw and surface material, causing less soil disturbance than he’s seen with other drills. Less disturbance means fewer weed seeds being lifted to the surface so they germinate, and the surface mulch remains in place to speed soil biology. The double disc provides accurate seed placement and seed depth is easy to adjust.

But it is perhaps the way the slot is closed which is the neatest part of all. With the slot at an angle of 25 degrees the tyred press wheel closes it by pressing down on top. The wheel acts as a depth wheel and the angle of the main disc is such that there’s a downward draught force. Discs can smear in wet ground, but whether this will be better than other discs such as the John Deere 750A or not is difficult to say.

Tony is really enthusiastic about the machine and farmers will find the sub £30k price for the 3 metre appealing, as they will the low cost of parts.

The 4.8 metre Weaving GD 4800T is sowning at 6.5 inches. Tony would prefer 8in.

Autocasting Oil Seed Rape

Tony is a big fan of autocasting – featured first in Practical Farm Ideas in Vol 4 – 4 (winter 1995-6) and produced this cost comparison table in fig 2.

Autocasting works well with well established zero-tilled land. The soil has a highly fertile surface, and the undisturbed soil is friable and good for the plant to root deeply. The seed gets put directly onto the soil surface and is covered with chaff and chopped straw. covered as the combine passes over and the seed is on the cleared strip between header and the seed covered with straw as the combine passes over.

Soil Quality

Sampling for the main plant nutrients has been done by Soyl and a comparison made over the years and the maps show a rising level of P and K, and none has been bought in for the past 8 years.

Earthworms clearly make a major difference to soil quality, and are essential if they are used as a cultivation tool.

Soil tillage methods and earthworms: Perhaps the most interesting is how close the reduced tillage land is to conventional ploughing and cultivating. Farmers might expect worms to be far more numerous if the soil is vertically tilled, yet the major difference is when no tillage is done at all. Worms create their systems of runs over years, can get to breeding. The worm has both male and female organs (hermaphrodites) and these are located in segments 9 to 15. When mating they get together with heads pointing in opposite directions and sperm is exchanged and stored in sacs. Eggs are laid around 27 days after mating, and populations can double in 60 days in worm farm conditions.

Fig. 3 compares worm distribution in conventional, reduced tillage and zero tillage soils.

Originally written and pictures by Mike Donovan – and published in @Practical Farm Ideas Magazine 24.3