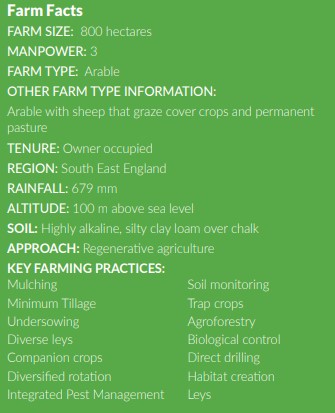

• Julian Gold is farm manager of 800 hectares of Hendred Estate in Oxfordshire on the edge of the Berkshire Downs. The farm typically has a high pH (8.2) silty clay loam over chalk soil and a 6-year rotation of oil seed rape (OSR), winter wheat, spring barley, spring or winter beans, winter wheat, winter barley or second wheat, then back to OSR. There is a small area of permanent pasture and a sheep flock graze the cover crops.

• He talks about motivations – how he transitioned from “the industrial bandwagon” of piling inputs into crops, lots of fertilisers, lots of chemicals, and being part of the problem, to being part of the solution – and farming in a way that is less harmful to the environment and biodiversity.

• He outlines his soil health and carbon capture strategy; explaining his primary aim is to grow big high yielding crops that are photosynthesising hard and to also grow cover crops wherever possible between winter and spring crops to try and keep root exudates. He tries to do reduced or no till (and direct drill) whenever he can – to minimise cultivations, and to return all the crop residues where possible. He also runs a 10m controlled traffic system which has reduced trafficking of the soil to 20%.

• He describes his multi species cover crops, how he manages them (including using sheep to graze them), and how he manages straw residues.

• He also describes his trialling of biological methods of pest control to build ecological processes on the farm and reduce his input bill. He talks about his involvement with ASSIST (a large research project with the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology looking at beneficial insects on-farm), where he has been growing flowering strips down the middle of fields (90m apart), and mentions some of the main benefits he has observed.

• He refers to the ways in which he wants to build on reducing nitrogen (N) use; including using under stories of clovers and yellow trefoil, and companion cropping.

• He talks about the impact of what consumers want on agroecological farming practices – and the importance of having a product you can get a premium for.

• Finally, he describes his perfect vision of a farming system and how he would like to see his farm, or the way that he farms, develop in the future. “If UK agriculture is going to reduce its carbon footprint to zero by 2040 (which is what the NFU wants to do), we can’t do that without reducing N fertiliser substantially.”

Interview with Julian

Janie Caldbeck spoke with Julian Gold, farm manager of Hendred Estate in Oxfordshire, as part of the Agricology farmer profile and podcast series (recorded in July 2020)

Please could you introduce the farm – what you farm and your general farming system and overall approach?

I manage the Hendred Estate which is about 800 hectares of farmable land, mainly combinable crops. We have a small area of permanent pasture and run a small sheep flock, we also graze on cover crops in the arable area, and we run a shoot for the Estate. The farm is on the edge of the Berkshire Downs, and it’s very high pH soil; 8.2 silty clay loam over chalk. We’re in a bit of a rain shadow so we tend to have very dry springs and summers. We practice a six-year rotation at the moment, which I had thought was a nice fantastic, diverse wide rotation but I’m increasingly thinking it’s needs to be way wider and way more diverse. We start with oilseed rape (OSR) and then it goes onto winter wheat, then spring barley, then spring or winter beans, back to winter wheat, and then winter barley or second wheat, and back to OSR.

We do get flea beetle problems but not as bad as some people. The rotation seems quite wide and ecologically friendly, but I think that it needs to be much more diverse and much more random. At the moment we tend to work backwards from the grain storage – so I have big grain stores with big bays, they hold 1200 tonnes of crop each and I tend to have big blocks of set amounts of crop each year. But what I feel is that from an agroecological point of view, I need to plant crops in a random way to help confuse the pests and diseases, particularly the black grass. It really relies on us having much more grain storage and smaller compartments so I can fit random crops in, that’s what we’re working towards.

Can you give an example of typical yields?

My rolling 5-year average is wheat is about 11 tonnes to the hectare, OSR is about 3.7 tonnes to the hectare, winter barley about 8, spring barley about 7. Bean yields are quite low, we really struggle with beans, particularly with our dry springs, they are probably in the high 2s, low 3s.

How did you enter the farming sector and why is sustainable farming using agroecological practices

important to you?

I grew up on a small farm in the Midlands which has got Grade 1 soil, it’s the only patch of Garde 1 land in Warwickshire. So I was on a farm with exceptionally high quality soil, and I didn’t realise that you could get soil in other places which wasn’t as good as ours until I started working in different places. I went to Australia between A-levels and college, and worked on a terrible, terrible farm in western Australia which should never have been cropped. Then I went to Harper Adams to do a HND. During my time at Harper Adams I went back to Australia and worked on another terrible farm which should never have been cropped. And then I worked on a root farm in East Anglia where they’d completely destroyed their soils with excessive cultivations and sugar beet potatoes. I left college, worked at home for a while, and then got a job with Sentry Farming in managing farms, so again worked on various farms over a short period of time, all with big soil issues.

From an agroecology point of view, the soil was the big thing that hit me first… I realised that there was soil and there was soil, not all soil was the same. Ever since my teens I’ve had this focus on trying to promote soil health, that has been my big driver for years. But apart from soil, I was still stuck on what I call the ‘industrial agricultural band wagon’ of piling inputs into my crops and lots of fertilisers, lots of chemicals, and I was part of the problem rather than part of the solution from the point of view of destroying the environment and harming biodiversity and insect life.

About 10 years ago I got a beehive, and again that was another big mindset change – suddenly my insecticide spraying wasn’t just damaging some ephemeral bees that were just ‘out there’ in nature, I was damaging my own bees. And when it becomes up close and personal, I think it’s really interesting because that can then trigger a mindset change. I really started to think about biodiversity, insect life, pollinators – about the wider ecosystem I was working in rather than just soil health. Over the last 10 years I’ve been really focusing hard on soil health and the wider ecosystem.

I have an analogy I use that sort of sums up my thoughts really – it’s this fact that industrial agriculture has been sabotaging its own factory premises. If you think of an analogy with a manufacturing industry like a car manufacturer, they have a production line producing cars which is generating their profit, but they also have a factory premises to maintain – which they do so out of their profits. But I think industrial agriculture for too long has concentrated on the production line, which is the food production. And if you see our factory premises as the ecosystem that we’re operating in, we haven’t been diverting money into maintaining the factory premises. Part of that is because there hasn’t been enough profitability in farming.

It’s not necessarily the farmer’s fault, but I’m really focused in now on my farming – as well as producing food and making a profit, I’m trying to maintain my ‘factory premises.’

Moving on to your focus on soil health particularly… I’ve heard you say that before you even start looking at nutrients for crop production (your usual such as hydrogen, phosphorous, potassium), the main nutrient that you focus on is carbon, because you basically need it to feed the soil before you start thinking about anything else. Could you describe your carbon capture strategy on your farm and the different practices that you carry out to do that?

A lot of what I say is to do with my specific farm situation because I’m not a mixed farmer, I haven’t got access to rotational lays or farmyard (FYM) manure. So I see my primary source of carbon as being the atmosphere. I really see myself not as a farmer, more as a photosynthesis facilitator. I basically want to take as much carbon out of the air as I can and put it in my soils. It’s a win-win.

The primary aim is to grow big high yielding crops that are photosynthesising hard and also grow cover crops wherever I can between winter crops and spring crops to try and keep root exudates. When crops are growing, a significant proportion of the products of photosynthesis go below ground as root exudates as well as going into plant growth. I’m trying to harness those root exudates into my soil to feed the soil life and soil biology. But I’m also trying to make sure that I don’t then re-oxidise that out. So we’re trying to do no till and scratch till as much as we can. We don’t want to do deep cultivations, we don’t to put the carbon there using photosynthesis and then go in post-harvest and oxidize the carbon by letting air into the soil with deep cultivations. So we try to minimize cultivations. Because I haven’t got access to a lot of compost and FYM, I return all my crop residues where possible, and that includes spring barley and winter barley straw which is very difficult. We struggle to grow crops behind chopped spring barley and chopped winter barley, but I’m loath to cart carbon off the farm.

And to fit in with all that, particularly the lack of cultivations as well, we run a controlled traffic system. We’ve been running that since 2012, a 10 metre controlled traffic system. So we’re not putting compaction in, we’re only trafficking 20% of our soil surface. We know where those wheelings are and we can take the compaction out on those wheelings if we need to. That enables us to direct drill and scratch till very efficiently because there’s no compaction.

Going back to the cover crops, you’ve mentioned the challenge of dealing with the residue from it. How

have you overcome that?

We have challenges with straw residues and challenges with

cover crop residues.

The cover crop residue challenge is we’re grazing them mainly with sheep – I grow a few different types of cover crops, my favourite are big, higher biomass, multi-species… So for the sheep now we’re growing multi-species cover crops with things like spring oats, rye, tillage radish, vetches, phacelia, a few stubble turnips, bit of forage rape – six or seven species, and we get those in straight behind harvest. And then from about mid-October time the sheep are grazing through the winter on those cover crops. By the time we get to the spring there isn’t much residue left, we just spray off what there is and then direct drill. I can’t graze certain cover crops in the same way, or I haven’t got enough sheep. So I’m experimenting growing cover crops with lower biomass i.e. spring oats, phacelia… where there’s much less biomass above the surface so it’s easier to deal with in the spring. We have a different range of cover crops depending on the situation. But I’m hoping with the machinery that’s becoming available now to terminate cover crops, that we can increase them as we go forward. If we haven’t got enough sheep to graze on our cover crops we can terminate them mechanically.

Straw residues have been a real issue for us – particularly growing the OSR after chopped winter barley straw. We change our chopper blades regularly, so this is an extra cost. We keep them sharp and change them regularly. We also find that the quality of straw chopping is the first thing that stops us combining in the evenings, when the grain moisture can be quite low still. If the straw chop quality deteriorates we have to stop combining because we know it will impinge on the OSR establishment. We powder our residues as much as we can to dust, combining in the middle of the day and using sharp chopper blades. We do a bit of raking – we have a cheap 10 metre Wyberg which we’ve spaced the tines out on and we use that on a light tractor with low tire pressures, off the control traffic lines, and rake at an angle if we have to. By all those techniques, we’re finding that we’re managing to grow crops in chopped straw, but it is a struggle. If we combine too late in the evening and the chop quality deteriorates, the OSR establishment deteriorates or disappears completely.

Spring barley is an even bigger problem. We have the rotation fixed so that after spring barley we either grow spring beans or winter beans – if we grow winter beans there’s a bit of time for the spring barley to rot down a bit to go through the drill with the winter beans. And also if we have to, we’ll rake at an angle. If we’re going into spring beans, we grow a cover crop behind the chopped spring barley straw. But that’s quite problematic and often components of that cover crop mix will fail, so I tend to put mustard and vetch in the mix – they usually take fine, even if other components of the mix fail.

So you’ve mentioned the challenges, do you have any advice or tips for fellow farmers who might be

interested in applying a similar approach?

It’s all about thinking about the whole integrated system – integrating the rotation with the cultivations with the cover cropping and the type of cover cropping… There are going to be problems in some areas, and it’s important to get the machinery right – it doesn’t necessarily have to be expensive – my 10 metre Wyberg cost me about £4,000 and we just took a third of the tines out, re-spacing them – so that’s a cheap straw rake. We’re operating secondhand drills. One thing that I tend to find with conservation agriculture systems and systems where you’re not doing much tillage, is you’re saving a lot of money on diesel and cultivation equipment, time in the field cultivating. But unless you’ve really pushed the boat out and bought something really expensive like a New Zealand Cross Slot, the chances are you’re going to need a couple of drills. I have a Dale drill and a Köckerling drill, both tine drills. They’ll work in different situations – the Köckerling will go through any amount of trash. The Dale drill will direct drill in the spring through a dry crust into wet soil conditions underneath, whereas the Köckerling will make a mess.

If we can go on to talking a bit now about another biggie for you, which is looking at biological methods of pest control. I know you’ve been involved in various trials, and traditionally flower margins are planted round the edges of fields… You’ve been involved in a project that’s trying to put these strips in the middle of fields. What were your motivations for doing this? Please can you describe the system that you’ve been trialing.

The trials are the ASSIST trials, which are government funded, multi-agency funded trials… It’s a five-year trial initially about achieving sustainable cropping solutions, we have various trials on the farm. My motivation for putting biodiversity and the homes of beneficials in the middle of fields is because I feel that historically farmers have used environmental schemes and put margins around the edge of fields. But with a margin around the edge of a big field, you aren’t necessarily going to be able to cut your use of insecticides because beneficials living in the margin aren’t going to go very far into the fields.

Alot of these beneficials i.e. ladybirds and carabid beetles only move up to a certain distance from where they’re living. So the theory is looking at putting homes for beneficials through the middle of fields in strips. In my field they’re 90 metres apart, three tram lines – we’re basically covering the whole field with beneficials. If you have a pest problem in a field, the beneficials can control it for you without you having to resort to insecticides.

Scientists involved in the trials infected my wheat tiers with aphid colonies, different distances from the wildflower strips, and then analysed to see how far out the ladybirds were going in controlling the aphids. It’s all about not just playing lip service to environmental schemes, which I feel that farmers have tended to do a little bit in the past, but actually making it useful. Can we save ourselves money, can it be much more useful than just a few pretty strips around the edges of big prairie fields?

Up until this point, what would you say are the main

benefits that you’ve observed?

A, it makes you feel good. If I’m having a down day and I walk out into my field with strips down the middle of my otherwise sterile, industrial agricultural prairies, and they’re all in flower and full of insect life, it’s just absolutely fantastic. I think a lot of this is mindset change, until you get up close and personal with the things that you can do on your farm and see what’s happening, it’s almost hard to visualise. No farmer that’s visited my strips has come into the field and said, “Oh this is terrible, look at all the wasted land you could be growing wheat on.” They all look at it and say, “Oh isn’t that fantastic!”

So visually they’re great. I think they are starting to work for us – this is anecdotal at the moment because the data hasn’t come back from the scientists. I have three fields in my ASSIST trial. One is business as usual, with no environmental strips round. Treatment two field has got environmental strips around the edge and various other things going on, the third has environmental strips round the edge and strips down the middle of the field. It all went into rape, they all got treated the same. We didn’t actually straw rape them because it was a very dry summer and I was worried about losing moisture for rape establishment. So there’s quite a high concentration of straw, particularly where the combine hadn’t spread it to the full 10 metres perfectly.

The two fields without the strips down the middle have got savage slug damage in the established rape, there are gaps in the field where there is no rape behind the thickest bit of the combine swathes, so strips of rape and strips of bare soil. In the one with the strips down the middle of the field I have 100% rape establishment. The same amount of slug pellets were applied on all of them, so I’m hoping that because I have many more carabid beetles living in that field in the strips, they’ve all come out and eaten the slugs…

Going back to the soil health again, it’d be interesting

to see if there’ll be any benefits in relation to that.

Benefits from high soil health are there whether you’ve got the in-field strips or not, because if you can get carbon and you can reduce the tillage and you can get fungal networks working, the mycorrhizal fungi working, you can get all the symbiotic relationships that are supposed to be there but modern industrial agriculture tends to work without… We can hopefully get higher, more robust yields. In these years when we have dry springs, I do find that my yields aren’t hit as hard as they might be, but alot of the benefits of environmentally friendly and high soil health farming are quite hard to actually pin down.

Anecdotally, I’ve been farming enough years to know that there are big benefits from high soil health – soil’s easier to work, it holds its moisture, yields aren’t as affected. When it’s wet it drains through better. Compared to a lot of people last autumn, we were able to do a reasonable amount of drilling. The fields got wet but they dried out quite quickly.

I think the big thing is nutrient availability. Going forward, we really need to work on reducing nitrogen (N) use. As you build soil carbon and have all this nutrient retention in the organic matter and all the soil biology cycling it, the mycorrhizal fungi bringing phosphorus in, the organic N that can be mineralised for the crop… if we can start cutting down our N fertilizer and letting the soil feed the crop like it’s supposed to, we can save money on fertiliser and help minimise the environmental damage that we do with N fertiliser with its carbon footprint and its emissions… Again, it’s a win-win deal.

We’re doing a bit of companion cropping and playing about with legume understories. We’ve established some clover, but we’ve used yellow trefoil, which is too vigorous. We’re trying to see if we can maintain it in the rotation and direct all the crops into it. This year that trial has got spring beans into yellow trefoil, and yellow trefoil is massively out-competing the spring beans. So I’ve got to go back to a small seeded white clover which isn’t as competitive but it is harder to establish under an arable crop.

Last year I drilled spring oats into an established winter bean crop, then we harvested them and separated them in the cleaner. This year we’ve planted a big two hectare, 30 metre-wide strip of alternate rows, spring beans and spring oats drilled in the same field. The rest of the field is spring beans, and the field next door to it is just spring oats. It’s a relatively good experiment because they’re the same soil type. We’re hoping the beans will give the oats N, and the two crops together will help cut down the pests and diseases, the oats will get less crown rust, the beans will get less chocolate spot, and the black bean aphid will be slowed down a bit….

What economic benefits or cost savings have you experienced from farming in the way that you do?

The controlled traffic system has given us savings that are tangible. My frontline tractor with our old system used to do about 850 hours a year, and we do about 400 – 450 hours a year with it now. Time in the field is dramatically reduced. So there are fuel and machinery savings… Obviously the machinery lasts much longer if it’s doing half the work so there are tangible savings from working wide, shallow, no till.

I did an economic trial last year but unless you’re doing replicated trials, I’m loathe to put misleading information out there into the public domain…but my gut feel is that the agroecological system I trialled made me more money. Unfortunately N is the whole driver, it drives the speed of the hamster wheel. If you’re putting a lot of fertiliser, a lot of N on, it’s driving disease which you then need a lot of fungicide for and you’re killing the good guys as well – you need growth regulators to keep it standing up. You’re feeding the weeds as well, so you need herbicides, and you’re spending a lot of money on the N, it’s driving all your other costs. But if we can back off with the N, the crop can get its N much more slowly from soil organic N that’s been mineralised slowly.

A lot of crops varieties have been designed for industroagricultural systems, they don’t necessarily root very well. They’re designed to yield really well with a lot of fertiliser inputs, and they haven’t necessarily got the best disease profiles. That’s in contrast to agroecological type farming where we’re putting less N on and we want crops with big root systems which will explore the soil profile and that’ll have symbiotic relationships with the soil life. How do we know with some of these modern varieties that they haven’t bred out their ability to have symbiotic relationships? Maybe they just don’t interact in the same way?

It’s about having the right varieties and the right crops to be able to feed themselves from the soil. The hamster wheel just needs slowing down. And I suspect if we slowed the hamster wheel down we’ll find it’s a win-win – farmers will have nicer farming systems, the planet will be healthier, bank balances will probably be better or maybe not much worse, and the consumers will have healthier food which won’t have such a chemical cocktail of residues in it and will be more nutritious.

How would you like to see your farm or the way that

you farm develop in the future?

If UK agriculture is going to reduce its carbon footprint to zero by 2040, we can’t do that without reducing N fertiliser substantially. The use has to go down somehow, and that’s what I’m working hard on. It’s difficult growing winter wheat if it is your main cash crop, it’s difficult to make big inroads into N reductions. I would like to move towards almost all spring cropping in an ideal world – if I could get my overheads low enough to withstand the lower gross margins… Moving to all spring cropping so that I’ve got cover crops virtually on my whole acreage through the winter, big high biomass cover crops… So with lots of legumes, lots of biodiversity in the different lengths of rooting systems, exploring the root profile, hoovering up nutrients and putting them into the cover crop biomass ready for the spring crop. It would involve destroying cover crops either mechanically or with sheep and livestock, and then planting spring crops, spring beans, spring barley, spring oats, even spring wheat, that require much lower N inputs, my overall use of N would dramatically reduce. My environmental footprint, carbon footprint, would be massively reduced from a carbon point of view. The sequestration be up, and the emissions would be down because of the lack of N fertilizer and the extra cover crops growing everywhere.

The perfect vision of a farming system for me would be all spring crops, the whole farm growing high biomass multispecies cover crops, stock rotating round the farm, mob grazing cover crops, and with a lot of environmental strips in all the fields – a regenerative agricultural system which isn’t organic but is a long way away from our industrial farming systems that a lot of people have been operating until recently. The six million dollar question is… I’m a farm manager, not a farm owner, so can I sell this vision to our owners? And can we reduce our fixed costs low enough, our big overheads, our labour and machinery to be able to withstand a lower output system?

Visit the Agricology website www.agricology.co.uk to view the full farmer profile and listen to the podcast. Agricology is an independent collaboration of over 40 of the UK’s leading farming organisations sharing ideas on sustainable farming practices. We feature farmers working with natural processes to enhance their farming system and share the latest scientific learnings on agroecology with the farming community from our network of researchers. Subscribe to the newsletter or follow us on social media @agricology to keep up to date and share your questions and experiences with the Agricology community.