Farmers who only ever feed pasture plants to their animals often remark on the positive effect this has on their bank balance. Sara Gregson talks to one such farmer and also reveals the findings of a recent economic survey of members of the PastureFed Livestock Association (PFLA)…

Balbirnie Home Farm in Fife has been in Johnnie Balfour’s family for generations. It is a mature mixed farming business running to 1,300 hectares and used to grow cereals, beans and vegetables, with some permanent pasture alongside an intensive beef finishing system. A 250-cow robotic dairy business was closed in 2005 because it was losing money. The soil ranges from silty loam to sandy loam and average rainfall stands at 700mm.

“When my father retired in 2018, I was reading a lot about regenerative farming and had recently completed a post-graduate course in Sustainable Agriculture,” says Johnnie. “I had also joined the Pasture-Fed Livestock Association whilst living in Hong Kong, where I had been for three years. It sounds a bit surreal, but looking out over all the skyscrapers and high-rise apartments was when I realised I wanted our herd at home to be pasture-fed.”

Previously the beef cattle had been fed a barley creep feed when grazing with their mothers. They were brought inside in October and fed a high cereal diet. Mainly Simmentals crossed with a big Charolais terminal sire, some finished with carcases weighing more than 400kg, grading U and 4R at around 16 months of age.

“They looked impressive and were securing high prices at the market,” says Johnnie. “But we were actually spending much more than we were getting back. There were a lot of fixed costs from the daily use of tractors, feeder wagons and labour, we were ‘buying in’ barley from the arable side of the farm and making a lot of conserved forage that had to be made, stored and carted. I was much more interested in not having machinery doing the jobs that the cattle can do for themselves.”

Mob grazing

Now the cattle business looks very different. There has been a move away from the big continental breeds towards Salers and Aberdeen Angus easy-calving bulls, which have been chosen so that calves pop out unaided and producing progeny that grow well off grass alone. The most significant change has been the management of the grass. Being part of a three-year mobgrazing discussion group, as part of a Soil Association Scotland Field Lab scheme, has helped.

“We have learned so much, sharing the highs and lows of trying to start mob grazing,” Johnnies admits. “As well as the permanent pasture we have at the higher end of the farm (250 metres), we now also have short term mixed leys growing within the arable rotation. The fields growing cereals and vegetables were never rested, and now they have a rejuvenating multi-year ley within them. “We graze the 170 suckler cows in two mobs and aim to do daily moves. At all times we are trying to lengthen the rest period – this is the most important element of mob grazing. This is what we really need to focus on, not the amount of grass that is growing or the residual left after the cattle have grazed.”

Calves used to be weaned at the beginning of October but if there is enough grass, the aim is to keep them out until Christmas. The youngstock will then overwinter on kale with big bales of silage.

“Mob grazing forces you to do a plan,” Johnnie explains. “By working out expected supply and demand, animals can be sold early in a season if a grass shortage is predicted weeks down the line. Some stores we sold this spring made really good prices.”

Pasture for Life

Balbirnie Farms became Pasture for Life certified last year, meaning none of the cattle ever eat anything other than grass, pasture or forage crops their entire lives. They are sold to Macduff Beef, a Pasture for Life certified butcher.

“We are definitely going in the right direction, but still have much to learn. In our beef enterprise we have already cut our variable and fixed costs significantly, our cattle are happy and healthy, and their actions are improving the soils beneath their feet, which is all very positive.”

Gathering The Evidence

A recent research project called ‘Sustainable Ecological and Economic Grazing Systems: Learning from Innovative Practitioners’ has given some hints to what effect feeding cattle and sheep on just pasture has on Gross Margins. The research was carried out by the UK centre for Ecology and Hydrology (UKCEH), Lancaster University, Natural England and SRUC, and led by Dr Lisa Norton of UKCEH. The project was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Economic and Social Research Council, the Natural Environment Council and Scottish Government.

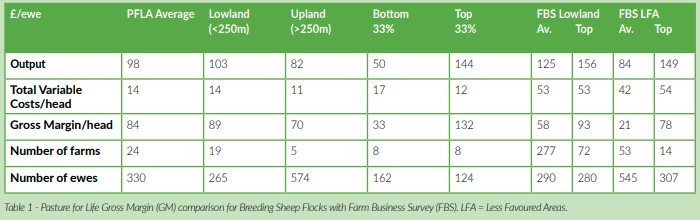

Fifty-six Pasture-Fed Livestock Association (PFLA) members were interviewed on all aspects of their farming systems, including their finances. Their Gross Margin figures (Output minus Variable Costs) have been compared to the Farm Business Survey (FBS) for England – see Tables 1,2 and 3.

The top PFLA farms are making more Gross Margin at £132/head than the top FBS farmers at £93/ head (on the Table 1 in green).

PFLA farms based in the uplands have a much better Gross Margin at £70/head than the average upland farm in the FBS survey at £21/head (on Table 1 in blue).

The main reason for these results is that the variable costs on the PFLA farms is much lower than for the FBS farms – at £14/head average for PFLA, compared to £53/head for the lowland FBS average and top farms (on Table 1 in orange). These costs would include concentrate feed and vet and med bills. The output from the PFLA farms is almost double that of the benchmarked FBS farms at £1,158/ head for the average compared to £516 and £540 for the FBS averages for lowland and upland systems (on Table 2 in blue). The probable reason for this is that the PFLA farms are selling their calves finished, whereas the FBS farms are selling six-month-old stores for other farmers to finish.

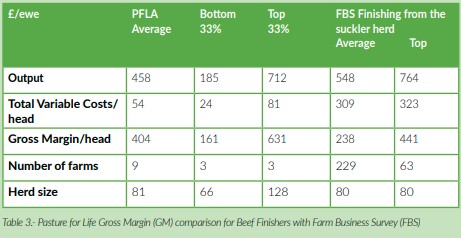

However, despite PFLA farms keeping their cattle six months longer or more, the variable costs across all the systems were remarkably similar, from £193/head for the PFLA average and £216/£214 for the FBS averages for lowland and upland (on Table 2 in green). In essence, PFLA farmers are achieving twice as much output for the same amount of variable costs. When looking at an enterprise level – the FBS lowland farms are achieving an income of just £18,576 (£516 x 36 cows), whilst the PFLA farms are gaining £59,058 (1,158 x 51 cows). Output from the PFLA farms is significantly lower than the FBS documented enterprises at £458/ head compared to £548/head (on Table 3 in blue). This will probably be because the PFLA cattle are native breeds and their growth is not being pushed on by grain feeding.

However, once again there is wide variation in the variable costs between the two approaches, with PFLA costs sitting at £54/head compared to £309/head for the FBS sample (on Table 3 in blue). This will be due to PFLA animals being fed no expensive grain or concentrates. This leads to the PFLA farms having a much healthier average Gross Margin of £404/head, as opposed to the FBS farms at an average of £238 (shown on Table 3 in orange).

In future, the PFLA is looking to gather and produce enterprise costings data down to Net Margin level, to highlight differences in fixed costs between 100% pasture-fed farmers and conventional lamb and beef producers.