Mark is a farmer and agronomist from Withybrook in Warwickshire. After starting with ADAS in 1996 and working with NIABTAG, AICC and Agrii he was awarded a Nuffield Scholarship to evaluate the role agronomists play in stewarding pesticide use.

Think of Denmark and you might imagine bacon, pastries, Hamlet and Carlsberg. You might also think of a country which relies almost exclusively on ground sources for its drinking water supply; probably the best drinking water in the world. To maintain this particular public good, Danish farmers have been subject to environmental protection laws and restrictive practices on pesticide use for 35 years. One of the most valuable visits on my Nuffield Scholarship tour was with Søren Thorndal Jørgensen who leads the coalition of farming and agronomy interests and negotiates with the strong environmental protection lobbies in Danish politics. His experience is one which I believe will be crucial to gain in the next decade here in the UK. Pesticide use is under a political spotlight in the context of a new National Food Strategy, revision of the National Action Plan for sustainable pesticide use and from across the English Channel and North Sea with the EU’s Farm to Fork strategy and its 50% pesticide reduction target by 2030. UK legislative response is currently in gestation.

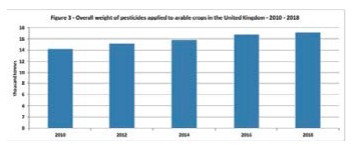

I sense a change in the attitude of farmers as well as legislators and the pesticide supply chain which is palpably different to that which I saw three or four years ago. That’s when I first made an organised attempt to evaluate our relationship with pesticides and the role that agronomists of all kinds play in that evolving affair. Successive product revocations and the build-up of resistant weeds, pests and diseases have had their effects on use. Temporarily use has increased (think of the pre-em and triazole “stacking” we talked about more enthusiastically a few years ago) but this last hurrah may be giving way to a progressive movement towards regenerative practices which rely less on pesticides and more on the adoption of resilient systems. Groundswell captures the zeitgeist. Although the mood seems to have changed, the data to support this apparent shift in attitudes is not as easy to detect; the Pesticide Use Survey reports increases in pesticide used on arable crops measured by both weight and treated hectares.

The effects of pesticides on biodiversity are Implicit in their role and we all want, or at least are under pressure, to use less. But how?

Integrated Pest Management has long been heralded as the solution to pesticide reduction, but as the graph shows, in the decade prior to 2018 we used increasing amounts while simultaneously adopting IPM plans as a compulsory part of the Red Tractor assurance schemes. Other studies have also recorded concurrent increases in pesticide use and adoption of IPM practices. It’s perfectly possible to use more pesticides while simultaneously using more cultural controls. It’s clear we need to do more than fill out an IPMP to demonstrate our sustainable approach to pesticide use. Back to Denmark and of all the policies, good and bad, put in place since the 1980’s the word from the coal face is that the recipe for success is simple: engage with the debate, make reasonable changes, evolve the approach and communicate the success.

At the heart of the Danish experience has been the evolution of the metrics used to assess trends in use. Weight of product and treated area have limitations on their usefulness as they take no account of the equivalent effects of the products being used. A step in that direction was one which Denmark took in recording Treatment.

Frequency Index (TFI) which measures the number of full rate equivalent applications made to a crop. TFI is a progression from weight and treated area as a proxy for pesticide related harm. It takes some account of the relative equivalence of different pesticide products because it relates to the full recommended rate for a particular product which was authorised partly by reference to its potential unintended effects. TFI also has the benefit of being very easy to calculate. Software providers would have very little work to do to allow this measure to be generated as a report for scales right through from field,

farm and agronomist, through to region and nation. It would provide a comparative, up to date picture of our pesticide use at the touch of a gatekeeper icon. The initial targets put in place for reductions in TFI were predictably missed in Denmark. Those which were implemented in France more recently have also been missed. The thing these two examples have in common is the lack of stake-holder engagement when setting targets. When more stakeholder engagement in Denmark was sought and the targets were evolved then the success started to flow.

Learning points from these experiences for effective pesticide reduction strategies incude:

• Select appropriate metrics

• Engage the stakeholders when targets are determined

• Review progress and evolve the approach

Since completing my Nuffield Scholarship, I have taken the study further with regard to pesticide metrics and their role in reduction strategies, applying the academic rigour of an MSc course at Abersystwyth University to what I learnt on my travels. I incorporate my combined conclusions in the way I believe we should apply them to the UK context and believe we should:

• Introduce Treatment Frequency Index as a reporting requirement for Red Tractor assurance schemes on the basis of 3 year rolling averages to reduce seasonal bias.

• Agree reduction targets with stakeholders through a body tasked with the Responsible Use of Pesticides in Agriculture (RUPA)

• Keep the system under review. This process represents a journey, not a destination.

This process must be led by a coalition of interests. By using use the word led I imply the need for leadership. Leaders in this area have been scarce to date and that void needs to be filled before the opportunity to lead change is supplanted by the obligation to carry out change according to poorly conceived legislation.

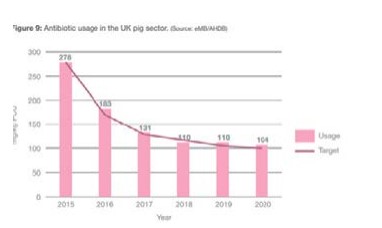

The drop in Antibiotic use in UK Pigs

In all my Nuffield travels I didn’t find a better example of this approach than the organisation Responsible Use of Medicines in Agriculture (RUMA) in the UK which has widespread industry support. It was founded in 1997 and was tasked with overseeing the responsible use of medicines in livestock production. In May 2016 Jim O’Neil published a report titled “Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally” which applied the sort of political pressure on antibimicrobial use which we are seeing with pesticides today. RUMA created their Target Task Force, the mission for which is to move closer to optimal use of antibiotics.

RUMA members’ acceptance that historic use was, in some areas, super-optimal has resulted in reduction targets that have both improved their production systems and is satisfying the objective of reducing antimicrobial use. Results have been impressive (as in the graph from RUMA’s 2020 report) and are credited with the avoidance of draconian legislation. It may be a coincidence, but the active ingredient loss experienced in plant protection products does not seem to have affected animal health products in the same way. The leadership and success evident in animal health product stewardship is something the UK pesticide industry should be trying to emulate.

There are some further parallels between this process and the way net carbon emissions are calculated which has evolved more rapidly in recent years. Exemplary leadership has pushed the goal of carbon Net Zero to the top of the agenda.

Although all these reduction strategies need to adopt common measurements and agree targets, there is a different finishing line between pesticides and carbon. Agricultural activity has the capacity to sequester carbon at different rates and can offset the unavoidable element of associated carbon emissions, so while we may achieve net zero, we cannot achieve absolute zero emissions. Unfortunately, the same offsetting opportunities do not exit with pesticides Perhaps the target we should aim for with pesticide use should be a net zero impact on biodiversity. Zero use may be a target for some stakeholders, but I cannot quite yet envisage a world where we are in an overall better position with zero use of pesticides, given their potential to augment food security through their judicious use. Then again, in 1996 I said I couldn’t envisage the time when I would want to use the internet.