As with many aspects of regenerative agriculture, farmers seeking UK-based research to confirm positive features seen in their fields from bale grazing, draw a blank. Sara Gregson reports on an Innovative Farmers Field Lab looking to address this.

The list of benefits of outwintering beef cattle on bales of conserved forage that have been placed in the field the previous summer, is impressively long.

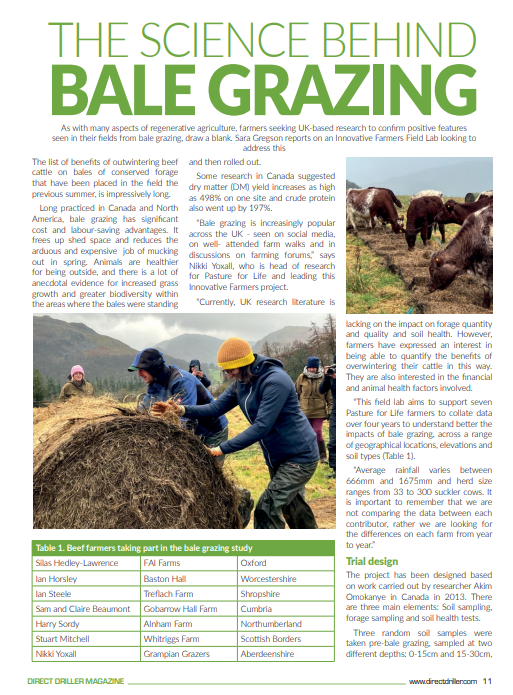

Long practiced in Canada and North America, bale grazing has significant cost and labour-saving advantages. It frees up shed space and reduces the arduous and expensive job of mucking out in spring. Animals are healthier for being outside, and there is a lot of anecdotal evidence for increased grass growth and greater biodiversity within the areas where the bales were standing and then rolled out.

Some research in Canada suggested dry matter (DM) yield increases as high as 498% on one site and crude protein also went up by 197%.

“Bale grazing is increasingly popular across the UK – seen on social media, on well- attended farm walks and in discussions on farming forums,” says Nikki Yoxall, who is head of research for Pasture for Life and leading this Innovative Farmers project.

“Currently, UK research literature is lacking on the impact on forage quantity and quality and soil health. However, farmers have expressed an interest in being able to quantify the benefits of overwintering their cattle in this way. They are also interested in the financial and animal health factors involved.

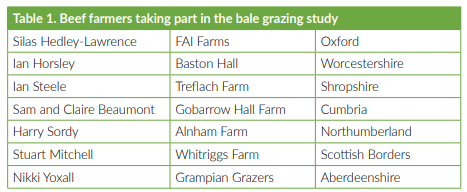

“This field lab aims to support seven Pasture for Life farmers to collate data over four years to understand better the impacts of bale grazing, across a range of geographical locations, elevations and soil types (Table 1).

“Average rainfall varies between 666mm and 1675mm and herd size ranges from 33 to 300 suckler cows. It is important to remember that we are not comparing the data between each contributor, rather we are looking for the differences on each farm from year to year.”

Trial design

The project has been designed based on work carried out by researcher Akim Omokanye in Canada in 2013. There are three main elements: Soil sampling, forage sampling and soil health tests.

Three random soil samples were taken pre-bale grazing, sampled at two different depths: 0-15cm and 15-30cm, using a 45cm soil auger. These were sent for soil nutrient analysis for nitrogen (N), phosphate (P), potassium (K) and sulphur (S), pH and soil organic matter (SOM) and electrical conductivity (EC).

These measurements were repeated in August 2023 and will be taken again this August and in August 2025 and 2026.

For the forage sampling, the farmers fenced off up to three one metre square (1m2) areas in the field to take a grass sample in August 2023. This was to mimic a zero-year bale grazing assessment.

In the same year, forage dry matter (DM) yield was measured in three random 1m2 quadrats in the green areas where bale grazing was carried out in the winter of 2022-23.

For the soil health tests, assessments are being undertaken pre- and post-bale grazing in autumn and spring each year, including Visual Evaluation of Soil Structure (VESS), an earthworm count, percentage of bare earth and water infiltration. Photographs are also taken in spring, summer and autumn. These are logged using the Soilmentor app or using the farm’s own recording software.

Soil analysis will be undertaken by NRM and the data is being collated by and analysed by a research assistant working for Pasture for Life. The project also has the support of Dr Hannah Davies at Newcastle University. It will also be reviewed by the Pasture for Life Research Group, which consists of farmers, scientists and researchers.

Cost benefit analysis

Added to the physical data being analysed, AHDB is also supporting the project by funding and carrying out an economic evaluation of each farm to compare bale grazing as an alternative to winter housing. At an early stage, AHDB’s grass, forage and soils specialist Katie Evans, says that reduced labour and bedding costs are clearly the biggest difference between the systems.

“There are a many different reasons for giving bale grazing a go,” says Ms Evans. “It can offer a low risk, yet much cheaper overwintering option for many beef farmers, using less labour, less machinery and less fuel.

“There are also the opportunity costs of having an empty shed. For some it is about how they want to spend their winters – outside or sat on a tractor for hours each day.

“Many farmers feel their land is too wet or their rainfall too high to bale graze. But done correctly and carried out to suit the needs of each individual farm, it can be done. All the trial farmers have been doing it for some years now, and rather than causing great damage, all have experienced healthier soils and much livelier ecosystems because of it.”

Case Study

Silas Hedley-Lawrence – FAI Farms, Oxford

Silas Hedley-Lawrence is an organic tenant farmer working for FAI, which farms 567 hectares on the banks of the River Thames near Oxford. For the past four years, he has been using bale grazing as a tool to cut costs, while increasing soil health and biodiversity.

In the summer, the cattle are rotationally tall-grass grazed in paddocks on the flood plain, moving every day. In winter they graze the slightly higher 80ha parkland, which has been set up into 160 half-hectare day-cells, with the appropriate number of bales that has been worked out they need to sustain them (five in winter 2023). Each winter cell is only grazed once.

“The cattle trample seeds falling from the bales, which are made on other more biodiverse parts of the farm, boosting biodiversity,” Mr Hedley-Lawrence explains.

“We don’t have to muck out the sheds in spring, reseed or sort out trashed fields, despite being on heavy clay. The pasture comes back every year more diverse and more productive.

“In May and June they are filled with colourful wildflowers and we also have rare cattle egrets; dung beetle numbers have bounced back and barn owls and hares are now thriving.”

Mindset change

Mr Hedley-Lawrence says bale grazing requires a mindset change – similar to the one needed by farmers when they started rotational grazing, as opposed to set stocking a few years ago.

Making it work requires doing a feed budget and planning six months in advance of winter. It is also crucial to defer the grazing for when the cattle arrive on 1 November. Mr Hedley Lawrence shuts up the park on 1 August to stockpile the forage. When winter grazing, he is looking for 75% utilisation, with 25% left and trampled into the soil.

The hay bales are made from the low-lying meadows in summer, wrapped with netting and moved immediately to their winter positions, so there is no double-handling. Everything is set up by the end of August.

“It is important to always have a plan A, B, C and even a D, which might be housing the cattle as the last resort. This is the ‘adaptive’ part of Adaptive Multi-Paddock (AMP) grazing. Despite very wet winters, we have never made it to D yet!”

The calves stay with their dams and are weaned in April, a month before the cows calve again. The beef calves are 100% grass fed and now finish at 22 months of age, rather than 28 months they used to take when housed and fed cereals.

Other benefits include cost savings from £2.43/cow and calf/day/ when housed to £1.04/cow and calf/day when bale grazed, along with all the ecosystem benefits. For example, four years ago infiltration rates through the soil in the park took more than two hours. In the same field, this has now fallen to 30 seconds, which means the soil has much better drainage channels and the fields are much less likely to flood.

“After four years, grass growth is now similar or greater than when we started farming regeneratively,” says Mr Hedley Lawrence. “The soils are still heavy clay but are healthier. This has allowed us to increase stocking rate and has built resilience into the system and the farm can now cope better with the adverse effects of climate change.

“This is not an overnight fix – it takes time. And there is risk in transition. But once a farmer gets to the other side, they are very glad they have done it. I advise farmers to take small steps at the start and then build up from there.”

Read more from Silas Hedley Lawrence at www.grassfedfarmer.com or follow him on Instagram @grassfed_farmer.com