Written by George Hepburn from Aiva Fertilisers

With the amount of rain we have had and the poor crop conditions this year, the availability of phosphate is going to be critical to maintaining yield potential. In this article, we will explore the chemistry behind it and how important biology is to release it.

Not only is phosphate vital for the roots and shoots early on, but it’s also needed throughout the growing season. It acts as the engine of the plant, creating energy for many critical processes.

According to the latest science, when Phosphorous is applied as phosphate, the majority of the nutrient is ‘locked up’ by the anions in the soil. This makes the application of P without a carbon source highly uneconomic, and as the index builds in the soil, the availability to the plant diminishes.

Most soils in the UK have significant reserves of phosphate, somewhere around 3-5000 kg/ha (3-5 tonnes) in the top 6″ and more below that if you have the depth of soil.

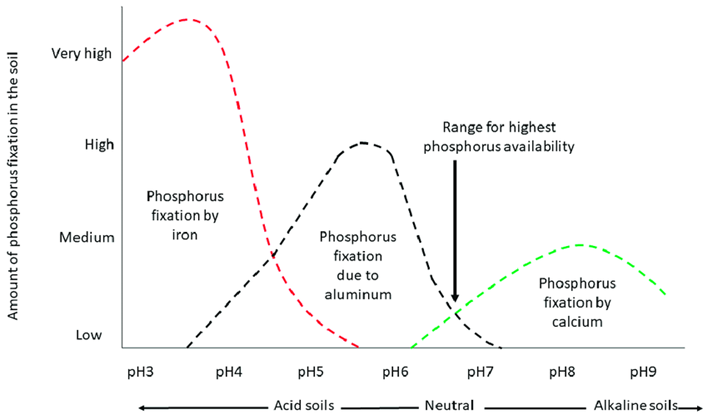

Phosphate issues have been seen in a soil index of 3, but no issues in the crop or tissue tests on an index of 0. There are even soils with a P index of 6 where foliar P must be applied to get some into the plant. It’s crucial to keep an eye on pH to ensure phosphate availability, as evidence shows that it’s significantly affected by pH.

At Aiva, we have the advantage of using a foliar P where the soil pH has no effect at all. The plant is fed directly, bypassing the soil entirely.

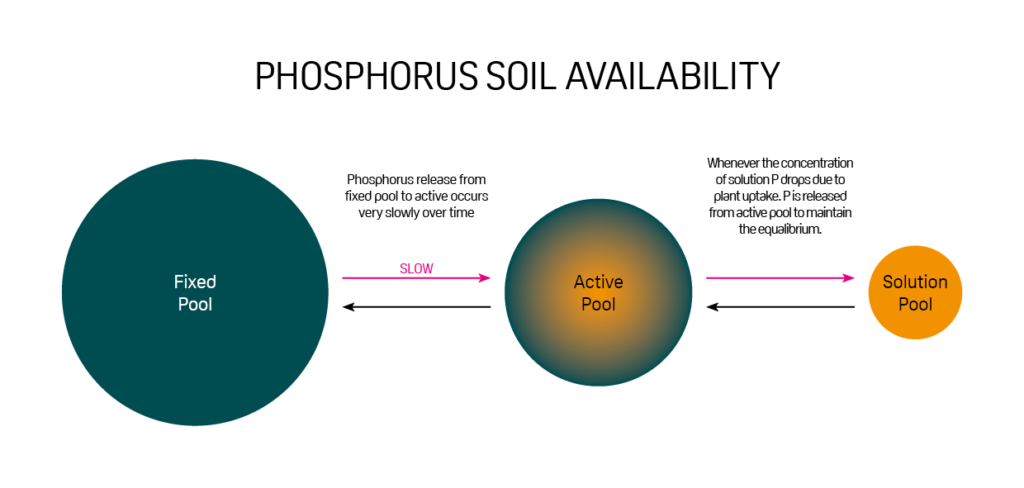

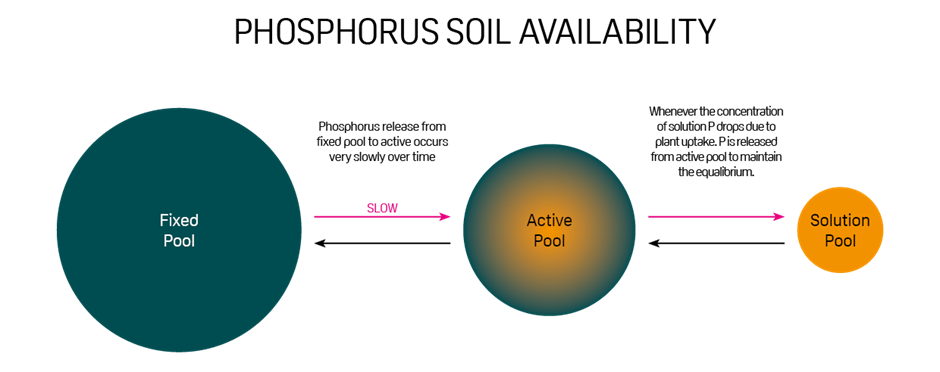

The diagram above shows how Phosphate is stored in the soil. It’s held in three pools. Soil reserves (approx. 3-5000 kg/ha), potentially available (500 kg/ha) and plant available (50kg/ha).

When you apply P fertiliser, it’s not in a form that the plant can take up. Within hours, or sometimes even minutes, it’s complexed with calcium, iron or aluminium and becomes part of your soil reserves. So rather than increasing your plant available P, you now have a bit extra in your bank, but you cannot access it. That’s why being able to use a liquid P that has a positive charge as opposed to a triple negative, is much more beneficial and efficient. It means that this P will not lock onto the soil and remains very available to the plant.

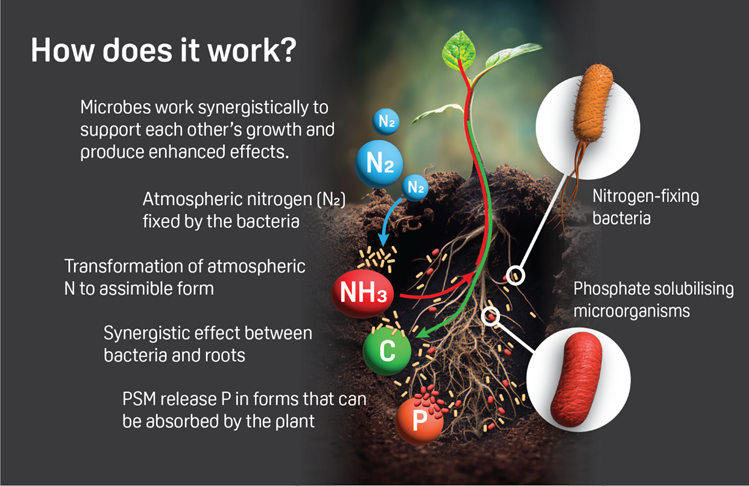

Unlocking your phosphate reserves is possible through soil biology. These microbes solubilise the phosphate and release it to their symbiotic partner. Instead of applying more fertiliser, we need to allow these microbes to thrive by giving them the right conditions. These microbes are aerobic, so having the correct balance in the soil of minerals, air, water and OM (carbon) is paramount. Tight or compacted soils will not release P in the same way, hence the need for fertiliser to bridge this gap.

The microbes need to be fed once they are in the right conditions. Many fertilisers turn these beneficial bugs off. Using a carbon source like humic or fulvic acid, fermented molasses, molasses, seaweed, compost, or FYM can help to stimulate the soil biology and release phosphate that was once locked up in the soil.

Adding microbes can also help release ‘locked up’ phosphorus and make it plant-available. The AIVA product BIOPLUS T has specific phosphate-solubilising bacteria that work to release Phosphorous from the soil. However, like any biological product, soil conditions, temperature, and moisture need to be right to get the most from the product.

If your soils are truly low in phosphate, then an organic input is recommended. FYM, compost, digestate, or sludge all comes with added extras in the form of other nutrients and will stimulate your soil and improve fertility. Unlike traditional ‘fertilisers’ like TSP and 20-10-10, it’s crucial to consider the unit cost of P when deciding. So, get the calculator out and go from there.