A full picture of soil health can be captured by a new ‘scorecard’. AHDB technical content manager Jason Pole investigates.

Not everything that matters can be measured. Not everything that can be measured matters. Wise words. Nobody would dispute that soil health matters. Now it can be measured.

The soil health scorecard is the product of a levy-funded partnership that tackled soil biology and soil health. It provides a simple way to measure the physical, chemical and biological condition of soil.

To develop the approach, the partnership identified core soil health assessment indicators that slot in with farm practice, along with the typical benchmark range(s) for each indicator to help reveal if a soil is healthy, getting sick or poorly.

Physical indicator

Visual evaluation of soil structure (VESS): For VESS, a spade-sized block of soil (about 30 cm deep) is levered out, leaving a side undisturbed to show topsoil structure. Assessments involve allocating a soil quality score by following the guidance in AHDB’s new ‘How to assess soil structure’ factsheet (which is laminated for use in the field). Where horizontal layers are identified, the worst-performing (limiting) layer is assessed.

Chemical indicators

pH: A soil’s pH affects its chemical (e.g. nutrient availability), biological (e.g. microbial activity) and physical (e.g. clay mineral aggregation) properties. It is easily revealed by an indicator test or laboratory analysis, with pH 6.5 to 7.49 the ideal range. Higher pHs may result in nutrient interaction issues or trace element deficiencies. Lower pHs, especially under 5.5, require immediate investigation and liming plans adjusted.

Extractable nutrients: A laboratory analysis of a representative soil sample can reveal phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium levels. Compared to England and Wales, Scotland has a different approach to nutrient analyses, which is accounted for in the benchmarks.

Biological indicators

Earthworms: Impacted by pH, waterlogging, compaction, tillage, rotation and organic matter, earthworms are an excellent soil health indicator. A spade-sized soil block is used for earthworm counts. In cropped land, 9 or more earthworms is good and 3 or fewer is bad. The AHDB website includes information on how to count earthworms, including ecological groups, and adults and juveniles.

Soil organic matter (SOM): SOM levels depend on many factors, including soil texture, use of organic materials, farming system and environmental factors, such as soil moisture and temperature. This complexity is reflected in the benchmarks, with different values for England and Wales, and Scotland. They also account for soil texture and rainfall region. For organic matter, measuring it periodically (using the same laboratory and method) to determine trends is as important as the absolute value.

Soil assessment tips

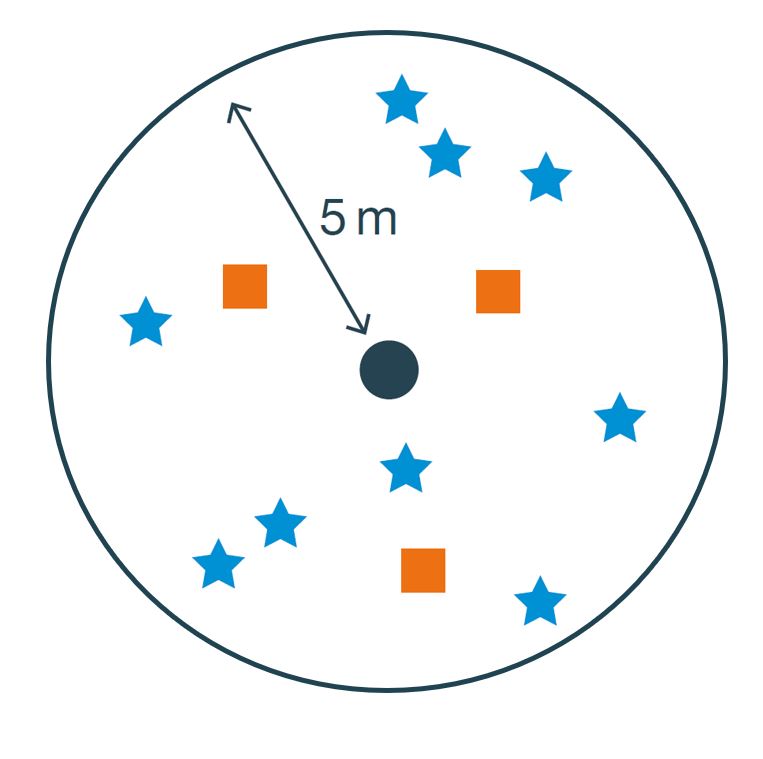

Ideally, gather information (observations and samples) for the indicators from representative field zones:

- Every three to five years (at the same point in a crop rotation)

- At the same time of year (warm moist soils in the autumn are often best)

- At least a month after soil disturbance and/or organic material applications

Simply record a centre point for the assessment area and take samples up to 5m away from it at random points. For VESS and earthworms, take three samples (illustrated by the orange squares). For other indicators, take several samples (illustrated by the blue stars).

Soil health scorecard

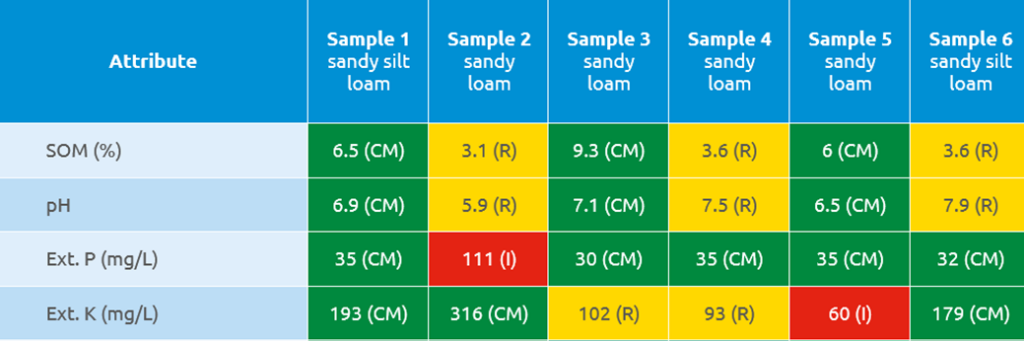

Indicator results (values) can be entered into an Excel-based version of the scorecard on the AHDB website. This automatically assigns a soil status for each indicator: continue monitoring (‘CM’ green), review (‘R’ amber) and investigate (‘I’ red).

In addition to the indicator values, the scorecard also uses three site characteristics – UK region, land use and topsoil characteristics – and features ‘management notes’ for each core indicator and soil status.

The scorecard approach has already been embraced by many AHDB monitor and strategic cereal farmers to:

- Facilitate a routine soil health check

- Identify production constraints

- Evaluate changes to practices

Limavady Monitor Farm

AHDB monitor farmer Alistair Craig

When Limavady Monitor Farm (Carsehall Farm) joined the AHDB network in 2022, Farm Manager Alistair Craig was already on course to harmonise the two sides of the business – a fifty–fifty split between dairy and cereal enterprises.

The farm (in County Londonderry) has around 120 ha of land on the sandy loams associated with Lough Foyle – a large tract of land reclaimed from the sea – and a further 80 ha on clay loam soils.

Alistair already put the farm’s manure to good use, reducing the fertiliser requirements for his arable crops and boosting SOM levels. It was a good start, but he wanted to go further and pinpoint the causes of poor crop performance in some fields.

In mid-November 2022, soil assessments were done at six sites, with scorecards used to help analyse the results. Alistair found VESS particularly informative. No soils were in a poor condition, which was a surprise. For example, sample site 1 was in a field previously used to grow potatoes, which was assumed to be in poor condition.

During the VESS, the field had Alistair’s first crop of winter oilseed rape companion cropped with a mixture of spring beans, sunflowers, vetch and buckwheat. The average (across three samples) VESS score was 3, which put the field in ‘moderate’ condition. It was not as bad as expected, and rooting was far more extensive than feared. The cropping diversity had already started to perform its magic on the hard-worked land.

The field also performed relatively well for other indicators, including the highest earthworm number recorded across the six sampling sites. Most (68%) of these earthworms were young (juvenile), which may indicate that the population was bouncing back from previous cultivations.

When Alistair saw the extent of the rooting, the high number of earthworms and the positive results from the laboratory analysis, he decided to sow the companion crop mix on a third of the farm in the 2022/23 growing season.

Encouraged by the soil structure assessments, Alistair used VESS on other fields. One was in poor structural condition, with very few pores and roots, after growing potatoes for two years. The field was planted with cereals in autumn 2022, which performed poorly. Alistair said: “Looking at the soil profile, it was not hard to see why the crop struggled to grow in this field.”

It was a cry for help, so Alistair reviewed the rotation to help the field recover. He took the field out of cereals and grew an eight-species cover crop mix, followed by a cash crop in the spring.

Other issues

The scorecard highlighted many areas that required attention (see the table, below), including some indicators that warranted immediate investigation (I) in some fields. For example, some of these red flags were associated with low earthworm numbers and nutrient levels far beyond the optimum for the soil.

Soil assessment results at Limavady Monitor Farm in soil health scorecards. All combinable crops, except sample 3 (permanent pasture). Scorecards also show results for indicators of microbial activity.

Alistair will continue to routinely review soil health, which will help monitor the impact of the boosted companion crop area. A full soil health scorecard review will also be done in the Monitor Farm’s final year.

Use the scorecard

The scorecard, which was funded by AHDB and BBRO, can be used for UK’s main cropping and lowland grassland systems. To access the scorecard and instructions, visit ahdb.org.uk/scorecard