Andrew Voysey, Head of Sales & Carbon, Soil Capital

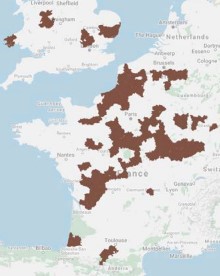

Seemingly at every turn, getting paid for carbon is the talk of the town. A flick through r e c e n t editions of Direct Driller is proof enough! As the independent agronomy firm that launched Europe’s first certified and multinational carbon payment programme for farmers, we at Soil Capital are certainly part of that momentum. Our scheme was launched in France and Belgium last year. It targets mainly arable operations and in the first season we signed up around 150 farmers from the more than 800 that expressed interest.

As we expand further in those countries, as of this Summer, we have also now brought the programme to the UK. We’re delighted to already be seeing British growers join the ranks of their European peers earning carbon payments each year. But this market is still very new. Every day, we talk to farmers who are (quite rightly) full of questions about how it works. In this article, I address 10 of the most common concerns we hear.

- There isn’t enough agreement

on how to quantify carbon

It is true that finding the right balance between modelling the impacts of farming practices and measuring soil carbon directly is a subject of ongoing effort. Scientists and technology developers are constantly bringing out new and improved approaches. This evolution will continue for decades, and so it should. We engage with it closely, but it is not realistic for most farmers to be experts in all these approaches and pick winners.

You can be confident in a scheme if it can answer three questions on this topic.

1. Is the independent standard they use widely recognised, ideally internationally?

2. Is the quantification method they use already widely respected in the marketplace?

3. Have serious companies already bought carbon via the scheme?

As an example, our programme (called Soil Capital Carbon) has been validated by an independent auditor against a standard from ISO (International Standards Organization). We use the Cool Farm Tool, backed by over 100 of the largest global food and beverage companies, in conjunction with soil analysis at the beginning and end of the five year certificate generation period. And when we launched, a range of companies including Cargill had already pre-purchased more than €500,000 of certificates.

You should insist on such clarity from all schemes you examine.

- I should wait because: the

market is young

Quite right, the market is in its early stages of development. Those not comfortable with some level of risk will be sensitive to this. But the devil is in the detail on the question of making a long-term commitment now. Is the scheme you are looking at clear about your rights to exit whatever contractual commitment they ask you to make? More importantly, are they clear about the consequences for you if you do so, such that you understand the cost of any flexibility they offer?

The challenge schemes face is that they have to balance farmer flexibility with buyer confidence. There are different approaches. Some schemes will impose a “claw back” mechanism so that if you break the contract, some of your previous carbon revenues might be owed back.

Our decision has been that farmers should be able to exit Soil Capital Carbon at any point without a fee, claw back or legal restriction. We manage market expectations by operating a so-called “buffer” – simply put, 20% of certificates you generate each year are set aside and not sold for you until 10 years later. If you leave our programme, the only consequence is that you forgo those future earnings as those certificates have to be written off..

- I should wait because: the

carbon price will rise

Analysts certainly expect the price of carbon to rise in general over the next decade, with some views pointing to quite dramatic hikes over this period. As in all markets, I am sure there will be ups and downs on the way. The real question is – once you are in a scheme, are you protected against drops in the carbon price and how do you benefit if it rises? We have found it important to be crystal clear on this topic. In our case, we commit in our contracts to protect farmers from downside risk and expose you to upside opportunity. This means we insist that your carbon will only be sold if it can generate you at least £23 per tonne and that, however high the market price of carbon goes, you will always get a fixed percentage of 70%.

- I should wait because: the

supply chain will want carbon

neutral crops

It is encouraging that farmers are seeing growing interest in carbon from the supply chain. However, I often hear the view that this means farmers shouldn’t get trapped selling their carbon to someone else, if the buyers of their crops will want it instead. There are two important realities here. First, you sell your carbon on an annual basis. It isn’t like selling mining rights for a lifetime! Companies are buying the claims related to the annual flow of carbon that you are either storing additionally in your soil or that you are no longer emitting. Provided the scheme has adequate flexibility to pivot to new buyers, you are positioned to adapt to changing market circumstances.

Second, if the supply chain is serious about carbon neutral crops, it will want credible, quantified and verified evidence that your crops are indeed carbon neutral. In other words, you will need to be using approaches like those developed by our programme and others. And if you are already monetising improvements in your carbon profile when the supply chain demands arrive, you are in a stronger negotiating position to insist that the supply chain compensates you fairly.

- I should wait because: the

Sustainable Farming Incentive

will kick in

As is widely known, the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) is in pilot mode today, with full details of how it will work in practice only to be confirmed once the few hundred farmers participating in the pilot have given feedback in the coming years. Nevertheless, the Government has stated that it expects the SFI to be compatible with private sector initiatives that pay farmers for carbon. The sorts of farming practices set to be incentivised by the SFI overlap strongly with those that will improve your carbon profile. Our experience as farm managers and advisors tells us that transitioning farming practices over 5 to 7 years is more prudent from a risk management and profitability perspective. It therefore makes sense to start now, generate carbon revenue from the private sector, and be well positioned to access SFI payments when they are fully rolled out in the years to come.

- My farm isn’t suitable

because…

It’s correct that the specifics of your farm matter – size, soil type, crops in your rotation, whether you are conventional or organic. Credible schemes should offer you honest advice based on the experience of real farmers. For example, we know that farms with less than 100 hectares of arable land are likely to find the cost of our programme difficult to justify, so we advise smaller farms to look carefully at their potential earnings before making a decision. Some schemes, including our own, offer simulation tools for this purpose.

Some farmers seem to believe that carbon payment schemes are only suitable for organic systems. This is certainly not the case in our programme, where we are seeing very traditional, conventional operations, organic farms and everything in between finding opportunities to improve their carbon profile – whatever they produce.

You should find the scheme that works best for your operation – because some may have constraints – rather than shoehorn your farm into a scheme even if the fit is not there.

- Joining a scheme will force me

into certain practices

Some will, yes. Most common is the requirement to commit to never plough. While a small proportion of farmers can make this commitment, this can obviously be an unacceptable constraint for most. Our view has always been that carbon payment programmes should never prescribe to farmers how to farm. Local context always matters and nobody knows that context better than the farmer and their local advisors. It is important to make it clear what practices will improve your carbon profile as these are the sort of practices that you will want to continuously improve for a scheme to make sense for you: replacing synthetic inputs with organic inputs, minimising soil disturbance, maximising ground cover with living plants, diversifying your rotation and integrating agroforestry are all changes that help improve the carbon profile.

In our view, good schemes should then provide detailed analytics, benchmarking, case studies and simulators to help you make the right decisions for your farm. But they certainly shouldn’t prescribe practices.

- I already store carbon – these

schemes don’t benefit me

Yes, be careful. If you have been direct drilling consistently for a number of years and increasing the organic matter you feed into your soil, you may well be storing carbon overall through your arable operations. If a scheme requires you to show improvement only on your own historical practices to generate carbon revenue, this could create a perverse incentive for you to “reset” your carbon profile with the plough for a few years and then revert to your previous practices. We have already heard of such stories in Europe.

There are alternatives. For example if you join Soil Capital Carbon with practices that result in net sequestration of carbon which you initiated systematically within the last 20 years, we use an alternative baseline to your own historical practices. This is derived from analysis of common practice in your region and is typically a slightly emitting baseline. This means you can be rewarded for continuing to apply these good practices.

- I don’t want to give companies

buying my carbon the right to

pollute

This is something we hear often. And it’s understandable – if farmers are bearing the risk of changing their practices to improve their carbon profile, why should another company benefit without doing anything to reduce its own emissions? This is really a question about carbon offsetting. When it is companies in the same food supply chains as farmers buying the carbon, the dynamics are quite different. My advice to farmers is to check with schemes what claims they are allowing companies with no supply chain relationship to the farmer to make, because all are not equal. A scheme can enable full carbon offsetting to companies – whereby they can use carbon credits generated by farmers to offset their own emissions – if that scheme uses a standard that is recognised by the International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance (ICROA).

In the UK today, there are no such schemes available because the relevant standards haven’t been fully adapted for a UK context. Soil Capital Carbon, which generates carbon certificates against an ISO standard, therefore does not allow companies to offset their emissions if they have no supply chain relationship to you. Instead, they get what the leading NGO in this space calls a “results based claim” – the right to talk about their support for your carbon improvements, but without using that to formally offset their emissions.

- I don’t know how much I could

really earn

I find myself instantly sceptical when a scheme presents carbon payments as the new “road to riches” for farmers. Often, this kind of marketing material doesn’t reveal the assumptions made about soil types or pace and scale of practice change and should be treated with caution. Schemes should present real case studies from farmers already in their programme, including the specificities of how they are achieving their earnings. Even better, schemes should provide simulation tools so that farmers can test the earnings potential of their specific circumstances and ambitions before they make a commitment.

When we work through this process with farmers we speak with, the right kind of response is that the earnings on offer from Soil Capital Carbon are modest but meaningful. Without doubt, for the right farm profile, the programme more than pays for itself. The incentive to generate new revenue is very often a welcome reward for the effort and risk of undertaking new practices. But new revenues from carbon should be seen as the cherry on the cake of practice change. Even more significant are the cost savings and operational resilience that can be achieved as soil health is continuously improved.

There are plenty of other questions that we field from farmers about the carbon markets and our particular programme every day. You should be full of such questions and you should do your due diligence carefully. But with the right perspective on how to navigate the offers that are emerging, this does not need to be overwhelming or paralysing. On the contrary, an exciting world of new opportunity is emerging and there are plenty of reasons why it makes sense to get involved sooner rather than later.