Written By Laura Barrera and first published on AgFuse.com

In 1995, Pennsylvania farmer Steve Groff was speaking at an event when he asked the audience the question:

Do cover crops pay off?

His thinking at the time was that he had been no-tilling since 1982, and maybe if he no-tilled long enough, he wouldn’t need them. Ray Weil, a soil ecologist with the University of Maryland, happened to hear his question and approached Groff about doing a cover crop study on his farm. It turned into a 12- year project, from 1995 to 2007. It was in 1999, four years into it, Groff got the answer to his question. That was the year he had a drought, and the corn that was grown on previously cover-cropped ground out-yielded the corn on non-cover cropped ground by 28 bushels per acre.

“That’s all I needed,” Groff says. “Ever since that I’m totally committed to cover crops.”

Talk to most farmers who have been using cover crops and you may get a similar story. They’re a long-term practice for protecting and improving the soil, which may also translate into protection and improvements for cash crops. The longer you use them, the more likely you’ll see a return on investment. But what about the short-term? Are there benefits growers can experience in their very first year of using cover crops? The answer is: it depends. A variety of factors can influence the early benefits of cover crops, including the soil’s current health and conditions, tillage practices, species selection and overall management.

The poorer the soil, the faster the results

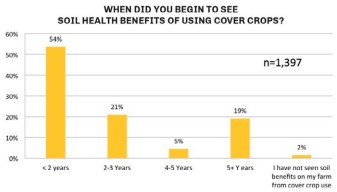

One of the fastest changes that can occur from cover cropping is the improvement of soil health. In the 2016- 2017 Cover Crop Survey Annual Report, 54% of farmers said they believe that soil health benefits from covers began in the first year of use. While covers can help any soil, Groff, who now runs a cover crop consulting business, says that cover crops seem to help a poorer soil quicker.

“If you have 3-foot deep topsoil in Illinois, you’re not going to see a dramatic difference in the soil as you would in maybe another soil that’s on a hillside, or rocky, or sandier,” he says

Eileen Kladivko agrees. The Purdue University agronomist says that one of the earliest changes farmers may see in their early cover-cropping years is an improvement in soil aggregation, especially in soils with low soil tilth and organic matter, such as 1.5% or less.

Another potential early benefit is less soil crusting, which can result in better seedling emergence and uniformity. “It depends on the year, it depends on the soil,” she explains. “If you have a severe thunderstorm shortly after you’ve planted and before your seedlings have emerged, having something like a cover crop on the surface can reduce that issue.” That goes in hand with preventing erosion, especially for those growing low-residue crops like tomatoes, corn silage or seed corn.

“And those are also places where cover crops are easier to fit in because they have more time after harvest,” Kladivko says. “You can actually get more growth and different kinds of cover crops, because you’ve got a longer window in the fall to get things established than if you do if you wait until after field corn harvest to seed the cover crops.” She notes that some of these possibilities would be more obvious for famers who are tilling than for no-tillers. “If they’re in no-till and they don’t have any significant erosion problems, then they may not notice that kind of benefit.”

Preventing rills and gullies pays off

While it’s difficult to calculate a return on investment for most of these early cover crop benefits, one effect that can result in a direct economic benefit is the prevention of rills and gullies. One farmer told Kladivko he usually had to fix the beginning formation of rills and gullies on his highly erodible soil. But just one year of cover crops prevented them from forming, saving him time and fuel. “Even if you don’t worry about how much soil is washing down the river — how much of that $10,000 an acre soil you just let leave your farm — the fact that you had to actually go and do something with the beginnings of a gully, to this farmer was worth time and money,” Kladivko says.

Trapping nitrogen now for future crops

Kladivko admits that this does not pencil out for a farmer who is renting land and is looking for a return on one year of cover crops. But for those who own land or will be farming ground for several years, cover crops can keep nitrogen from leaving the field and build up their soil nitrogen bank account. “If 20 pounds of nitrogen was just going down the drain, now you’re keeping it in the field,” she says, adding that covers can scavenge up to 30 pounds of nitrogen. If you’re growing a legume, it’s even more.

Unfortunately, growers can’t “withdraw” from that soil nitrogen bank in the first three years. Most of the nitrogen is recycled into the soil organic matter, Kladivko says, but at some point there will be enough built up that farmers can cut back on their nitrogen. “It’s certainly going into that account, they just can’t draw on it.”

Cover crop top growth can aid water availability and weed control

It depends on how much cover crop growth there is, but if farmers end up with a good mulch from it, that can increase soil water infiltration rates, Kladivko says. It can also reduce evaporation rates from the soil, which means there’s the potential for greater water availability for the cash crop at some point in the summer. “The rainfall that you do get will last you a little longer,” she says. “That’s a potential benefit in year one, depending on the year and on how much topgrowth they allow.” The amount of cover crop topgrowth can also help in the fight against weeds, particularly those that may be herbicideresistant.

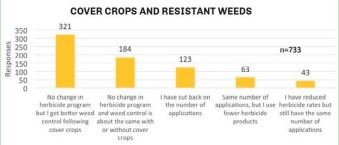

“I know some of our weed scientists at Purdue get very concerned with people saying ‘You’ve got cover crops, you don’t need any kind of herbicide or weed control, that’s all you need,’” she says. “But they say it can provide another tool for weed control in addition to herbicide. For winter annual weeds, I think in general they think they can be pretty effective.” In the 2016-2017 Cover Crop Survey Report, 44% of farmers said that while they’ve made no changes in their herbicide program, they’re getting better weed control following cover crops.

Best cover crops to begin with

For farmers who are hoping for benefits from the get-go, Kladivko says grasses like cereal rye, wheat or barley, are good ones to start with because they grow faster and have fibrous roots. “Something with a fibrous root is going to help hold that soil together and help provide good cover,” she says. For growers looking for some additional weed control, Groff says that cereal rye before soybeans is a good fit. In fact, the Cover Crop Survey Report specifically asked respondents about their experience with cereal rye on herbicide-resistant weed control, and 25% said they always see improved control following cereal rye and 44% reporting “sometimes.” The remaining 31% said they never see improved control.

Groff also recommends pairing oats with radishes, calling them the “cover crops with training wheels” because they’re hard to screw up. They also provide tangible benefits to the soil early on — the word Groff most often hears from growers is “mellow.” That mellowness is more noticeable with radishes because their deep taproot help alleviates compaction, but oats will also improve the soil tilth as its roots die in the spring. Kladivko recommends that radishes not be used alone because their size can leave the soil erodible. Management of the two is easy because they’ll both usually winterkill, so farmers don’t have to worry about having to deal with a living crop in the spring. “It’s easier to plant into, you don’t need special equipment on your planter,” Groff says.

But they do have to be planted on time — at least 6 weeks before your average first killing frost — to achieve decent growth, which may be a challenge for farmers with later harvests in northern locations. Black oats are another good beginner option that can be easily terminated with Roundup or a roller/crimper and decompose quickly for easy planting conditions. Legumes are another species Kladivko recommends for improving the soil structure, but unless they’re established early — in a corn-soybean rotation, they would need to be seeded before either crop was harvested — then they won’t achieve much growth in a fairly short window. In that situation, a grass is a better option.

4 tips for succeeding with cover crops from the start

Groff warns that while cover cropping is a simple concept, being successful with it is very complex. Below are some tips he has for setting yourself up for cover crop success.

1. Treat your cover crops like your cash crops. In all aspects, which includes preparing to plant them, knowing when to plant, and understanding that in some years it’s not going to be as good as others. “Cover crops are just like cash crops,” he says. “Some years they’re phenomenal results and some years they’re lacklustre due to weather and mismanagement.” He adds that cover crops will make a good farmer better and a bad farmer worse. “Just because you have a bad year of cover crops doesn’t mean that you’re a bad farmer,” he explains. “It just takes another level of management. If you treat your cover crops like your cash crops, you’ll stand a much better success rate of making them pay and making them work.”

2. Create or fulfill an existing planting window. Farmers who take wheat off in the summer and don’t follow with a double-crop have the easiest way of jumping into cover crops because they have a wide window of planting and cover crop growth. But for farmers who are growing something like full-season corn and soybeans, their options — and chances for cover crop success — become more limited. “Maybe you need to plant a field of shorter season corn or shorter season soybeans — take them off a week sooner, you’re setting yourself up for success then,” Groff says. “Because we’ve got good varieties out there now that are short-season, you’re not going to really sacrifice yield if you get the right one. You’re setting yourself up for a timely planting where you can actually see a difference. Success depends on management.”

3. Find a mentor. Anyone starting out with cover crops should find a mentor, and that doesn’t necessarily have to be a personal relationship, Groff says. Instead, farmers should look for the people who are achieving what they want to achieve and follow what they do.

4. Choose your own way. Everyone wants a cover crop recipe, but Groff says that like all other aspects of farming, farmers have to figure out their own road map.

“Just like you choose the corn hybrid you plant, the soybean varieties you plant, you don’t plant the exact same thing as your neighbour probably,” he says. “Eventually you’ll do what works on your farm, and that goes from species to seeding rates to creative ways to get them planted sooner.”