A wheat crop from plants which yield year after year has huge attractions for both the farmer and the environment. There’s no yearly crop establishment. Plants develop strength and get deep rooting. Carbon capture is enhanced. Creating a commercially viable perennial wheat has been a fundamental challenge that has been taken up by The Land Institute in Salina Kansas, which is focussing entirely on creating perennial varieties of annual crops.

Written by Mike Donovan, editor

Founded in 1976 by geneticist Wes Jackson, the Land Institute’s work is led by a team of plant breeders and ecologists in multiple partnerships worldwide, and is focused on developing perennial grains, pulses and oilseed bearing plants to be grown in ecologically intensified, diverse crop mixtures known as perennial polycultures. The Institute’s goal is to create an agriculture system that mimics natural systems in order to produce ample food and reduce or eliminate the negative impacts of industrial agriculture.

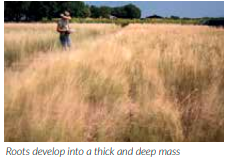

As an undergraduate Wes Jackson noticed the inherent robustness of the native prairie compared with the fragility and the increasing chemical dependency of the annual monocultures that constitute the American breadbasket. Every acre planted is an uphill battle against the natural order, which favours diverse perennial polycultures — deep-rooted, enduring plants that form synergistic communities that define the essence of resiliency as demonstrated by the Dust Bowl experience — when an extended drought hit the lower Midwest in the 1930s, turning tens of thousands of acres of native prairie that had been ploughed up to plant wheat into massive, deadly clouds of dust. Meanwhile, the undisturbed prairie, with its deep roots and highly evolved survival traits, remained intact.

Jackson’s fundamental premise is that humankind took a wrong turn when it began ploughing up the land and planting homogeneous annual crops. As he told Modern Farmer, “… there was a dualism that developed — wild nature, with virtually no soil erosion, and then us with the plough… Now we have not only soil erosion but chemical contamination of the land and water with fertilisers and pesticides and so on.”

Perennial crop solutions

Perennial crops are robust; they protect soil from erosion and improve soil structure. They increase ecosystem nutrient retention, carbon sequestration, and water infiltration, and can contribute to climate change adaptation and mitigation. Overall, they help ensure food and water security over the long term. Perennial grains, legumes and oilseed varieties represent a paradigm shift in modern agriculture and hold great potential for truly sustainable production systems. The Land Institute is using two approaches to breed perennial grain, pulse, and oilseed crops:

1. Domestication of wild perennial plants

2. Perennialization of existing annual crops.

Domesticating wild perennials

Farmers have been domesticating wild perennial plants for the last 10,000 years. This is the approach that resulted in many of our current crops. Domestication starts with identification of perennial species that have one or more desirable attributes such as high and consistent seed yield, synchronous flowering and seed maturation, and seed retention, also called non-shattering (a feature of non-shattering plants that hold onto their seeds like an ear of corn rather than disperse them over the landscape like a dandelion). Large, diverse populations of the crop are grown out at The Land Institute, and plant breeders select the best individuals for the traits of interest. These individual plants are then cross-pollinated, and the resulting seeds are planted to produce the next improved breeding population.

The Land Institute established the perennial wheat program in 2001 with the goal of developing perennial wheat that is economically viable for farmers and replaces the global food calories of annual wheat. Annual wheat is grown on more acres than any other grain crop, at 548 million acres worldwide, followed by maize at 445 million and rice at 399. Wheat accounts for 20 per cent of human food calories and more protein calories than any other grain.

The programme at The Land Institute creates perennial wheat hybrids made from crossing annual wheat species with wheatgrass species (especially intermediate wheatgrass, which is the same species being domesticated as Kernza®). The annual types include bread wheat and durum wheat used for making pasta. Many successful hybrids have been achieved between wheat and wheatgrass. They are being used to understand the genetic contribution of the annual and perennial parents. Other research partners around the world have made similar crosses between annual and perennial wheat. Twenty of the most promising crosses are being grown in nine different countries to see how particular genetic types vary in performance when grown under a broad range of environmental conditions. The best performers have a grain yield grain about 50-70% that of annual wheat cultivars.

Perenniality (the ability of the plant to regrow after grain harvest and to survive harsh winters and/ or summers) is also highly variable depending on environmental conditions. Some of the perennial wheat plants in Kansas have lived for more than six years. In other locations, stands of perennial wheat have persisted for many more years. Their breeding program continues to seek improvements on a number of plant traits including perenniality and yield. Although we see steady improvement every year, we expect it could take another 10-20 years to develop an economically viable perennial wheat variety.

With a goal as bold as “changing the way the world grows its food,” all partners are critical to success. They provide insight, data, operations support, connectivity, and an expanded community of brainpower and technical capacity. The Institute currently has research partners in 41 different locations around the world, but none in the UK. Global partnerships spread researchers’ knowledge and botanical germplasm across six continents with diverse climates and soil types.

Partners are helping to fully develop Natural Systems Agriculture, and plant breeding is a numbers game. The more experimental lines evaluated, the better the odds of developing superior, high-yielding perennial crop varieties. The Institute is dedicated to ensuring worldwide food security without compromising ecosystems.

In 1983, using Wes Jackson’s vision to develop perennial grain crops as inspiration and guidance, plant breeders at the Rodale Institute selected a Eurasian forage grass called intermediate wheatgrass (scientific name Thinopyrum intermedium), a grass species related to wheat, as a promising perennial grain candidate. Beginning in 1988, researchers with the USDA and Rodale Institute undertook two cycles of selection for improved fertility, seed size, and other traits in New York state.

The Land Institute’s breeding programme for intermediate wheatgrass began in 2003, guided by Dr. Lee DeHaan. Multiple rounds of selecting and inter-mating the best plants based on their yield, seed size, disease resistance, and other traits have been performed, resulting in improved populations of intermediate wheatgrass that are currently being evaluated and further selected by collaborators in diverse environments. Experiments are also underway to pair Kernza® with legumes in intercropped arrangements that achieve greater ecological intensification, and to utilise Kernza® as a dual purpose forage and grain crop in diverse farming operations.

The breeding programme is currently focused on selecting for a number of traits including yield, shatter resistance, free threshing ability, seed size, and grain quality. In the next 10 years, the Institute’s aim is to have a crop with seed size that is 50% of annual bread wheat seed size. Our long-term goals include developing a semi-dwarf variety and improving bread baking quality. Ultimately, we hope to develop a variety with yield similar to annual wheat and to see Kernza widely grown throughout the northern United States and in several other countries around the world. If that vision becomes a reality, you might see perennial grain in common staples found on grocery store shelves.

Plant breeders report increasing success

At the 2018 Prairie Festival scientists from the Land Institute explained the advances they were making in the development of perennial wheat and other crops. Lead scientist Dr Shuwen Wang explained that the process in the past year had created 297 new cross-bred, 570 embryos created and 9,176 single flower heads compared. He told the audience that research was being carried out in eight separate countries ranging from equatorial to temperate. The 2017/18 results were better than previous years, with some tests being done on wheatgrass which has an additional 14 chromosomesto regular wheatgrass.

The crossing work started in 2011 when the first set of crosses was made and this has now created more than 500 plants which are available for testing and breeding. This year they were very pleased to have produced five rows of uniform plants which shows it is possible to get close to stability, and the seeds generated are being sent to the overseas research stations for further evaluation and experimentation. Some will be crossed with annual cultivars and will also be involved in gene stacking. Dr Wang said there were agronomic difficulties in these experiments. The toughest of these is weed control. Plant numbers remain small and the susceptibility of each of them to chemicals is different. When the numbers of individual plants of each cross are so few the opportunity to try out different herbicides is small. He said that weeds in these test circumstances “grow like crazy”.

A similar problem occurs with fertilising. There’s no handbook to suggest the stages when the plant needs fertiliser, or indeed the compounds that are most effective. Research has shown that the perennial plants do better in mild seasons and have a tougher time in both high and low temperatures.

Kernza® Grain Goes to Market

The Land Institute developed the registered trademark for Kernza® grain to help identify intermediate wheatgrass grain that is certified as a perennial using the most advanced types of T. intermedium seed. The goal is to develop varieties that are economical for farmers to produce at large scale.

The aim is to create a recognisable and protected brand – they say “When you buy Kernza® perennial grain, you can be certain that you’re eating product grown on a perennial field that is building soil health, helping retain clean water, sequestering carbon, and enhancing wildlife habitat.” Patagonia Provisions was the first company to develop a commercial retail product for the mainstream marketplace. The company took the risk of product development and market entry for their product called, appropriately, Long Root Ale. A number of restaurants have taken up Kernza® as an ingredient, using the perennial growth as a marketing tool. Hopworks Urban Brewery in Portland, and Vancouver, brews Long Root Ale for Patagonia Provisions and has it on tap, in addition to the ale in four-pack cans being sold in Whole Foods in California. Bang! Brewing in St. Paul has a Kernza® beer available, as does Blue Skye Brewery in their home town of Salina.

Innovative Dumpling & Strand produces Kernza® pasta which they retail through Twin Cities-area farmers’ markets. There are a few other small-scale retail food outlets scattered around the country, but to our knowledge, those are the most reliable sources right now. Additionally, Cascadian Farm is excited to incorporate Kernza® into some of its foods, with expectations for products made with Kernza® available in retail markets by late 2019. Cascadian Farm has agreed to purchase an initial amount of the perennial grain which allows us to arrange with farmers to plant on commercial-scale fields versus the test sized plots currently being grown.

General Mills (parent company of Cascadian Farm) approved a $500,000 charitable contribution to the Forever Green Initiative at the University of Minnesota in partnership with The Land Institute, to support advanced research to measure the potential of Kernza to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions associated with food production, determine best management practices for sustainable production, and increase Kernza yields through breeding. The hope is that increased demand for Kernza® products translates into more growers and acreage dedicated to Kernza® perennial grain, resulting in more Kernza® in production and on shelves, which in turn encourages more research and development into Kernza® and other perennial grains.

Patagonia’s and General Mills’ early commitments to create a market for Kernza® are significant milestones. Yet the transformation to an agriculture and a food system based upon perennial grain crops is a complex and long-term endeavour. Other perennial grains, oil-seeds, and legumes require agro-ecological research beyond that which market forces alone can provide at this critical juncture. The Institute says “We have been leading this research effort for forty years and we welcome your support of our work to help sustain the next vital stage of this agricultural revolution.”

Kernza® grain is the first perennial crop from The Land Institute’s work to be introduced into the agriculture and food markets, but our researchers are currently working on others, including perennial wheat, perennial rice, perennial sorghum, and wild sunflower, with more to come.

Followup: The Land Institute, 2440 E Water Well Rd, Salina,Kansas 67401 https://landinstitute.org/

info@landinstitute.org