A new American study shows how regenerative farming practices — soil-building techniques that minimise ploughing, the use of cover crops, plant diverse rotations etc — affect the nutritional content of the food

Everyone knows fruit and vegetable are good for your health says the University of Washington News, but which of the dizzying array of options – organic, conventional, CSAs, local agriculture – are best for your health? The university has done a preliminary study, under the leadership of David Montgomery, a UW Professor of Earth and Space Sciences, which shows that the crops from farms which have adopted soil-friendly practices for at least five years had a healthier nutritional profile than the same crops grown on neighbouring, conventional farms. Results showed a significant boost in certain minerals, vitamins and phytochemicals that benefit human health. The experiment is described as preliminary because it has only included 10 farms across the U.S. Given the remarkable results there will be further research work carried out.

Crops from regenerative agriculture farms had 34% more vitamin K, 15% more vitamin E, 14% more vitamin B1 and 17% more vitamin B2 compared to the conventionally grown ones. The regenerative agriculture crops also had 11% more calcium, 16% more phosphorus and 27% more copper. (Jan. 27 2022 in PeerJ) “We couldn’t find studies that related directly to how the health of the soil affects what gets into crops,” said David Montgomery, “So we did the experiment that we wished was out there.”

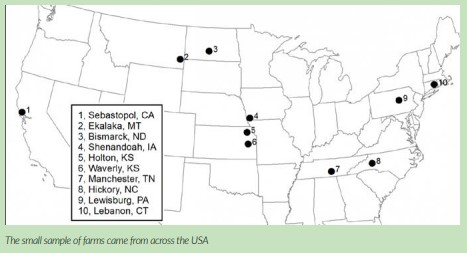

Montgomery designed the study during research for his upcoming book, “What Your Food Ate,” due out in June. His spouse, Anne Biklé, is a biologist and co-author of the study and the upcoming book. The authors collaborated with farmers using regenerative farming practices to conduct an experiment. All the participating farms, mostly in the Midwest and in the Eastern U.S., agreed to grow one acre of a test crop — peas, sorghum, corn or soybeans — for comparison with the same crop grown on a neighbouring farm using conventional agriculture. Co-author Ray Archuleta, a retired soil conservation scientist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, visited all the farms and sampled their soil in summer 2019. Farmers then sent samples of their crops in for analysis.

The study looked at farms across the U.S. doing regenerative agriculture, which uses soil-boosting practices. In eight of the farms (farms 2-9) the farmers planted the same crop as their neighbour to allow a direct comparison of the soil and resulting food. “The goal was to try to get some direct comparisons, where you controlled for key variables: The crop is the same, the climate is the same, the weather is the same because they’re right next to each other, the soil is the same in terms of soil type, but it’s been farmed quite differently for at least five years,” Montgomery said.

The study sites included the farm and ranch of co-author Paul Brown. Brown had met the UW researcher during Montgomery’s work for the 2017 book, “Growing a Revolution,” which toured regenerative farms in the U.S. and overseas, including Brown’s Ranch in North Dakota. Results of the new study showed that the farms practicing regenerative agriculture had healthier soils, as measured by their organic matter, or carbon, content and by a standard test.

“What we’re seeing is that the regeneratively farmed soils had twice as much carbon in their topsoil and a threefold increase in their soil health score,” Montgomery said.

Crop samples were analysed at lab facilities at the UW, Oregon State University and Iowa State University. The food grown under regenerative practices contained, on average, more magnesium, calcium, potassium and zinc; more vitamins, including B1, B12, C, E and K; and more phytochemicals, compounds not typically tracked for food but that have been shown to reduce inflammation and boost human health. Crops grown in the regenerative farms were also lower in elements broadly detrimental to human health, including sodium, cadmium and nickel, compared with their conventionally grown neighbours.

“Across the board we found these regenerative practices imbue our crops with more anti-inflammatory compounds and antioxidants,” Montgomery said.

Organic farms avoid chemical pesticides but they can vary in their other farming practices, such as whether they have a diversity of crops or till the soil to control weeds. Results from a previous review study, published by Montgomery and Biklé in the fall, show organic crops also generally have higher levels of beneficial phytochemicals than crops grown on conventional farms. The researchers believe the key lies in the biology of the soil – the microbes and fungi that are part of the soil ecosystem – as these organisms directly and indirectly help boost beneficial compounds in crops.

“The biology of the soil was really the part that got overlooked in moving to chemistry-intensive farming,” Montgomery said. “It may be that one of our biggest levers for trying to combat the modern public health epidemic of chronic diseases is to rethink our diet, and not just what we eat, but how we grow it.”

The study also included cabbage grown on a no-till farm in California and a single wheat farm in northern Oregon that was comparing its own conventional and regenerative farming practices and provided both samples. The study included meat from a single producer, Brown’s Ranch; the beef and pork raised on regenerative agriculture feed was higher in omega-3 fatty acids than meat from a conventional feedlot.

“The biggest criticism I would have of this study is small sample size – that’s why the paper’s title includes the word ‘preliminary,’” Montgomery said. “I’d like to see a lot more studies start quantifying: How do differences in soil health affect the quality of crops that come from that land?” The other co-author is Jazmin Jordan of Brown’s Ranch. The study was funded by the Dillon Family Foundation.

For more information, contact Montgomery at bigdirt@uw.edu