BYDV-resistant wheat is a relatively new concept in the UK that is creating significant interest among farmers and the seed trade.

Pressure from BYDV is building after the ban in 2019 of seed treatments that controlled the aphid vectors, while resistance to insecticide sprays is increasing and government policy on insecticide use is tightening.

Concern is not just confined to the traditional BYDV disease hotspots. Sub-clinical levels of the disease can also shave yields and erode returns.

Overall, annual yield losses in untreated crops average 8%, according to AHDB figures, but can reach 60%. And it is estimated that 82% of the UK’s wheat crop area is at risk from BYDV.

Clive Bailye is managing partner of TWB Farms, near Lichfield, a zero-till operation consisting of owned land, FBT and contract farming arrangements over several hundred hectares.

Whilst Staffordshire is not a high-pressure BYDV area, Clive suspects the farm’s wheat crops have been leaking yield.

“I haven’t sprayed insecticides for 16 years, but it would be very naive of me to say that we’ve never had BYDV since then,” says Clive. “We’ve not had any noticeable disease symptoms or yield loss, even in bad BYDV years, but in any given season sub-clinical levels of disease have probably been present in certain fields.

“That may well be costing me a couple of percent of yield, and that’s one reason why I’m keen to find out more about BYDV-resistant wheat varieties.

“The other reason is I want to maintain my no-insecticide policy at all costs. Whenever we use these synthetic products, or use unnatural techniques such as cultivation, we upset a balance. It might solve one problem but we could be creating another – there are consequences.

“Insecticides are more damaging to beneficials than most of us farmers realise. It becomes pretty obvious when you stop using them; on this farm, natural predators have increased in number to the point that they are doing the job for us.”

Clive believes the farm’s move to no-till, which began in earnest 16 years ago, is the reason why his no-insecticide policy has been so successful – visibly at least.

The move was initially a hard-nosed business decision, to reduce fixed costs and speed up operations as the farmed area expanded. However, it wasn’t long before Clive started noticing improvements in soil structure; fields were travelling better, creating wider operating windows, and plants benefited from the more friable soils.

“We stepped up our cover cropping, keeping soil covered with plants year-round, and introduced a more diverse rotation. We took the decision to improve soil and try to grow bigger yields whilst reducing dependence on synthetic inputs.

“But we never made a conscious decision to stop using insecticides. We had used them regularly in the past – it was cheap insurance. When we became more aware of the soil food web and how everything interacted, we decided not to use insecticides routinely, only if we had a problem.

“By the time we got to 2012, we realised that we hadn’t used an insecticide for over a year. We hadn’t had the need, and we still harvested decent yields. Was that luck? Rather than find out, we looked at what we could do to improve our chances of not having to reach for that insecticide can again.

“We were creating this more natural environment where nature was more in balance. It’s not perfect, of course, but we weren’t getting those extremes of problems.”

Clive admits that being in a low-pressure BYDV area will have helped. Despite that, he is now seriously considering what BYDV resistant wheats can do for his business.

“I only grow wheats that are resistant to orange wheat blossom midge, and adopting BYDV-resistant varieties is the obvious next step. It is exciting technology that comes at very little cost, especially when you consider that we can now claim £45/ha on land managed without insecticides. Suddenly that insecticide doesn’t look so cheap any more – there’s a significant opportunity cost.

“We also know that pyrethroids used to control aphids are less effective than they used to be. And, when you look at the direction of agricultural policy, it’s obvious that pressure on their use will increase. It’s probably only a matter of time before we will rely on resistant varieties to control BYDV.”

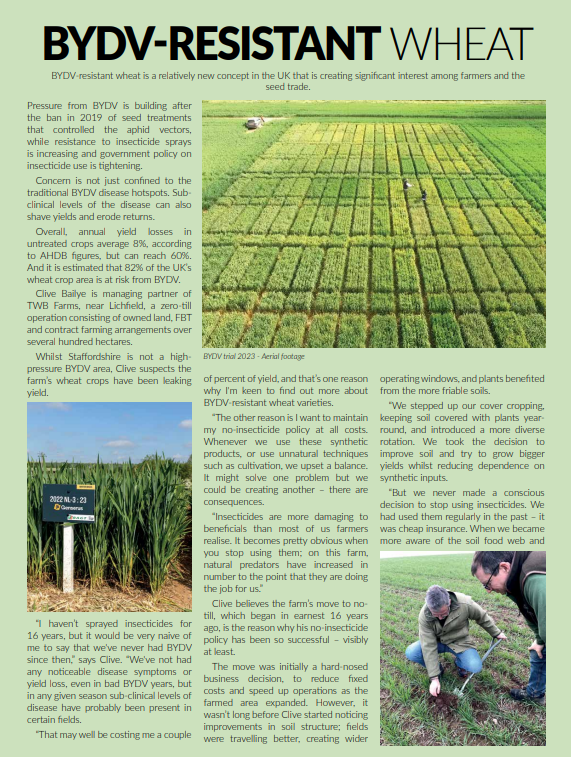

Clive is growing 15ha of RGT Grouse this season as a “look-see”, a high-yielding Group 4-type wheat with BYDV resistance. He will assess its performance over the weighbridge, along with an adjacent field of Dawsum and a further one containing a four-way blend of feed wheats, none of which are resistant to the disease.

All will receive the same inputs. “This will give us some idea of the relative performance of the wheats on this farm in a no-insecticide system,” says Clive, who will use ADAS Agronomics tramline trial metrics to analyse the results.

“We’ll take out a 3ha block in the middle of each field, which should minimise any variation on what are fairly uniform fields. Of course, it might be that it happens to be a good Dawsum year or a good Grouse year, but it will still be valuable to see how these varieties respond.”

In addition, each 3ha block will also be tested for virus loading by RAGT, using quantitative PCR. “We may not be able to visually see any differences between the trials, but this will reveal whether we have subclinical disease, and how much, in the three different areas,” says Clive.

“This will be the most interesting part of the trial for me, as it will indicate the extent of our BYDV problem and the potential value of BYDV resistance to our business.

“The trait costs a few pounds per hectare, and it wouldn’t take much loss to cover that. And you get peace of mind, ease of management and all the environmental benefits, and an SFI payment as well.

“Eventually this technology will be available in many varieties, like orange wheat blossom midge resistance. That said, given the potential benefits, I don’t see any reason why I wouldn’t include a BYDV-resistant variety on my farm now.”

New trials network aims to reveal true impact of BYDV on wheat

RAGT has established a comprehensive set of insecticide-free trials across the southern half of England and Ireland to assess the true impact of barley yellow dwarf virus on a range of wheat varieties.

Jack Holgate, RAGT’s arable products manager, says the aim of the trials is to provide growers with much-needed information so they can make the right varietal choices to help manage the disease.

“Official Recommended List trials don’t include this sort of assessment,” says Jack. “As a result, the effects of BYDV on the relative performance of wheat varieties are never considered. Varieties that are bred specifically to resist the disease never get a chance to show their true potential, so many growers are unaware of how the yield pecking order changes when the disease strikes.”

RAGT has set up an 18-trial matrix across the Midlands, south and west of England and in Ireland this season, using a range of popular commercial wheat varieties and some of the company’s current and pipeline BYDV-resistant Genserus (BYDV-resistant) varieties.

RAGT is working with several partners including seed merchants, Eurofins, AICC, agronomy companies and growers to establish the trials network.

“Some sites will be inoculated with BYDV-bearing aphids, others will be left to nature,” says Jack. “None will receive insecticide.

“We want to demonstrate what can happen under very high BYDV pressure and how Genserus varieties can cope with that, reducing costs and greatly easing autumn management. We also want to see what happens under a range of natural conditions. Growers can then decide for themselves whether Genserus technology should play a part in their risk management strategy.”

The trials will build on RAGT’s existing BYDV work, which reflect the resilience of the resistance trait, as seen in more than two decades of commercial production in Australia.

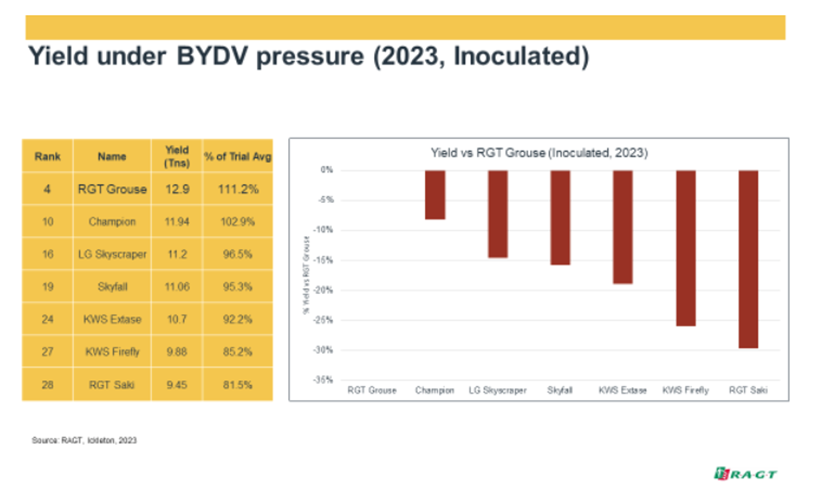

In BYDV-inoculated trials carried out at Ickleton, Cambridgeshire last season, seven Genserus varieties significantly outyielded their conventional counterparts. All plots received Recommended List-protocol fungicide and PGR treatments, but no aphicide.

RGT Grouse, RAGT’s main commercial Genserus variety, yielded over 8% more than Champion and almost 15% more than Skyscraper (see graph). Similar results were achieved in the two preceding years.

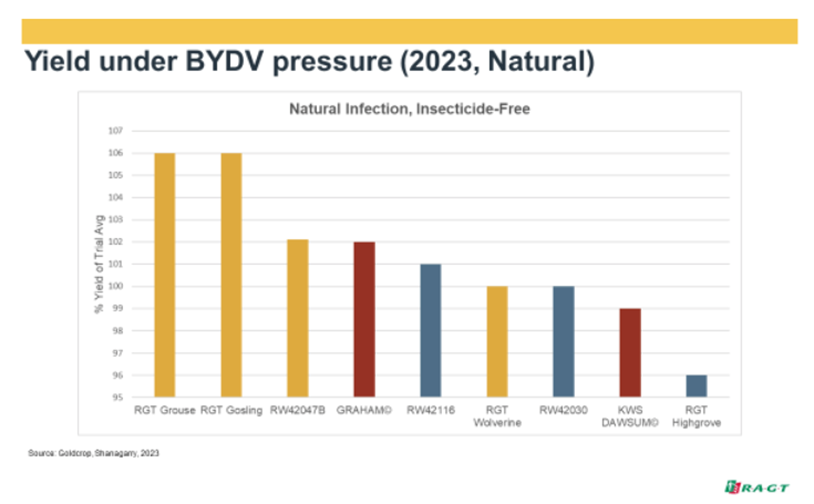

A trial carried out in County Cork by Goldcrop using natural BYDV infection also clearly demonstrated the strength of the trait (see graph).

“Genserus varieties took the top three places, with RGT Grouse equal top at 106% of controls,” says Jack.