Both cover crops and low-disturbance drilling are often seen as an easy way to improve soil health and performance

while also offering an opportunity to cut fixed costs. Where the transition is managed well, it can be very worthwhile

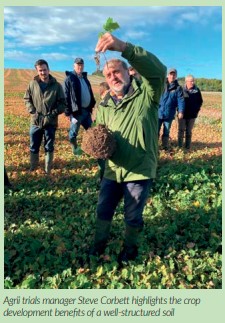

but in other cases, the journey to drilling nirvana can be a fraught with obstacles, explains Steve Corbett, trials

manager for crop advisers and research specialists, Agrii.

“The move to reduced cultivations or pure direct drilling is about first recognising where systems can change while preserving or improving financial returns,” he says.

The first consideration, he believes, is to understand why the existing system is arranged as it is. “Systems are often soil dependant. There is a need to identify the characteristics of a seed drill that are important to the operation and the objectives set by the manager. Any pre-drilling activities should also be considered, be it straw raking or shallow cultivations. There are situations where moving the top centimetre or so of soil will be highly beneficial and others where it is not necessary,” Mr Corbett says

The development of new technology, especially the ability to apply inputs in a precise manner, and to incorporate more than one activity at a time, namely fertiliser placement and sowing of cover or companion crops, should also be considered.

“There are many facets to the direct drill conundrum. Do you want to apply fertiliser at the same time, and will you be sowing more than one crop too? This is before we consider the diversity of crops in the rotation, time of drilling, be it early or late autumn, or on cultivated or non-cultivated ground. As precision technology comes to play an ever-greater role, growers may also want to consider the potential to integrate variable rate systems. This often needs to be considered before we think about coulter travel or lift and how effectively the various setups can handle surface trash,” Mr Corbett says.

Soil type is often both the determining and limiting factor. It tells you what you have to work with and will define the scope of your objectives. For example, will it easily take water, is it easy to create a tilth, how much air will be displaced if we were to receive a heavy rain shower? From here, we can see what is and is not feasible.

“At the basic level, soil type and condition will influence the choice between a disc or tine drill. These considerations rarely receive the time they warrant. Whether the disc runs at a slight angle with the coulter in its shadow or the disc is straight, and the coulter forces the opening will depend on the soil type and its condition. Issues such as hair-pinning, where the straw is forced into the opening, or where the opening can’t be closed after the seed has been placed because of the high plasticity of the soil, are often consequences of inappropriate drill choice or poor setup,” he says.

In a high weed pressure situation, especially black-grass, the considerations will be different again. There will be the desire to avoid bringing seed up to germination depth. In these situations, the minimal soil disturbance will be preferable. This would favour the Primera from Amazone or the Sabre tine from Weaving. In contrast, a winged tine is not suitable, but where more soil movement is desirable, the looser soil created by the likes of the Simtech or Cross-Slot allow for greater root development.

For many the move to direct drilling fits with the ‘re-generative’ movement, but it can take several seasons and a change to the system before the ground is properly ready to embrace the ‘re-gen ag’ philosophy. “It’s about earning the right to direct drill,” says Colin Lloyd. “Any drill in the wrong conditions will do a poor job and it concerns me that many growers are moving wholesale into direct drilling without first readying their ground. The transition phase is important as it paves the way for the drill that you have then chosen to fit your system,” he adds.

Manufacturers often make bold claims about details such as coulter pressure, but how much is enough, and do you really need masses of pressure? “Those with stiff, firm ground will need the ability to apply pressure, but where soils have been maintained in good friable order and compaction has been avoided, having the ability to apply 250kg of pressure per coulter is an expense that most can live without,” says Mr Lloyd. As efforts to improve soil biomass begin to deliver results, other design features become more important, such as the ability to deal with high quantities of material without becoming easily blocked.

“This is one reason why the Amazone Primera is popular with a section of growers. It has the size of frame and coulter arrangement to let material through. Other designs fail all to easily at this hurdle, especially if it is wet,” says Mr Corbett.

Having explored the available options, one of the last questions to be considered is: what happens if it comes wet?

“Most growers approach the purchase of a new drill from the perspective of wanting to do the job faster and more easily than before. Too often this comes at the cost of flexibility. “Most growers need at least two drills, probably a tine and disc, one of which may be a lightweight combination because it gives you the flexibility to go when conditions are less than ideal. Wet autumns are an increasing phenomenon, so systems need to be flexible otherwise performance suffers. It doesn’t mean you need to own it, but having access to a lightweight, mounted tine drill will often deliver the flexibility most growers require,” says Mr Corbett.

Profitability

Changing the system in expectation of financial improvements that aren’t then realised can be highly costly and stressful. To investigate this, Agrii has run long-term trials investigating the impact on performance from a system that seeks to balance cover crops and establishment regime across the rotation. “Few direct drilling advocates talk about yields or gross margin performance. Adopt the wrong approach for the situation or move faster than the transition will allow, and the impact to gross margins can be severe,” Mr Lloyd says.

A new seed drill won’t resolve a grassweed situation or increase biomass, so any system needs to first reflect the principles supporting good farming practices. “The condition of the ground, what are the mitigating circumstances, especially grassweed pressures, what crop and variety are you growing? These are the single biggest influence on performance.

“The Stow Longa rotations trial is in its seventh year; in the 2021 season we recorded a difference in winter wheat gross margin of £1,448/ha. This is partly due to a worsening grassweed problem, namely soft brome on a farm where this was not previously an issue, following five years of direct drilling in a section of the trial. The transition, especially on heavy land, must be managed with an understanding of the trade-offs,” Mr Lloyd says.