The Soil Farmer of the Year competition has been running since 2015, providing a platform for individuals and

businesses to demonstrate how soil management can build environmental and economic resilience. The competition aims to recognise, promote and champion farmers who are passionate about safeguarding their soils and demonstrates how despite the vast variation across the agricultural sector, sustainable management can be universal.

This year’s competition was conducted in association with and kindly sponsored by Hutchinsons and Cotswold Seeds, with ongoing support from Innovation for Agriculture. Traditionally the results of the competition have been announced on the main stage at Groundswell agricultural show, and 2021 saw a return to this practice following the cancellations associated with COVID-19 in 2020. The winning farmers from this year’s competition, Tom Sewell (Arable), Sam Vincent (Livestock) alongside Antony Pearce (Runner-Up) joined their fellow finalists ( Jack Martin, Mark Oldroyd and Rob Raven) in discussions of their soil health and regenerative management strategies through presentations to the Groundswell audience.

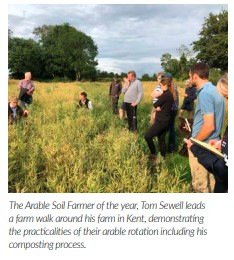

Following the announcement of the winners at Groundswell, the winning arable, livestock and runner-up farmers are invited to hold farm walks which are open to the wider farming community. These walks provide a platform for discussion and practical demonstration of how different businesses and approaches have focused upon soil health and land management.

Arable Soil Farmer of the Year, Tom Sewell from Kent led a tour around his farm during late July to discuss how his management approach has benefited business efficiency and soil health. As a previous Nuffield Scholar Tom has a passion for regenerative farming and sustainable farming practices centralised around no-till systems. A founding member of BASE UK, Tom himself has often contributed to Direct Driller magazine. The farm constitutes around 1500 acres split between 15 different landowners across 8 parishes, all of which is combined into a variable portfolio of soils from river silt to heavier and rockier ground.

Explaining his management approach as “We’ll get it right, but it takes time, effort and attention to detail”. Challenged with managing highly variable soils Tom has adopted a biologically focused approach, explaining “We maintain the good structure by not ploughing and instead using our worms”. An early adopter of a Cross Slot drill, Tom aims to simplify his arable system through minimising tillage where possible to keep costs low, adding “look at what you do and why you do it and see if you can cut it out”. Inspired by his Nuffield scholarship, Tom has transitioned towards no-till over a number of years, progressing from a disc press to a Simba Free Flow drill before settling on the Cross Slot.

To maximise the benefits soil biology can provide, cover crops and compost are used to encourage ecological processes to build soil structure and infiltration alongside carbon sequestration. Chopping straw is another practice that Tom has implemented, providing available residues for biological breakdown and soil organic matter building, he states “I just want to improve the soil, I use compost and feed the worms, they’ll do the rest”. Acknowledging that it takes time to build a resilient and dynamic biological system, new land taken into management is treated in this manner with the hope of adding “life back into it” following previous intensive arable or orchard management in other systems. Tom’s compost is usually produced from horticultural by-products such as spent strawberry and raspberry plants and is seen as vital to his system through encouraging plant rooting and worm activity; a key metric Tom uses across his farming landscape.

Through conducting worm counts and testing he approximates there to be 12 million worms a hectare on average.

Logistical challenges alongside those of soil type and weather guide Tom’s decisions on farm in matters such as cover crop selection. Understanding what a cover crop is being used for helps guide budgets and rotational choice, consequently resulting in there often being fields which are left without cover if it doesn’t suit the conditions. However, cover crops still constitute a key management practice implemented on-farm due to the benefits as Tom explains “The cover crop helps to provide that living root and to get organic matter and carbon back into the soil and help the soil to perform”. Increasing organic amendments and encouraging soil biology has enabled Tom to reduce nitrogen applications by 10% for each of the last three years. Balancing applications with a source of carbon helps Tom to continue supplying a above and below ground nutrient supply with fewer kilos of nitrogen.

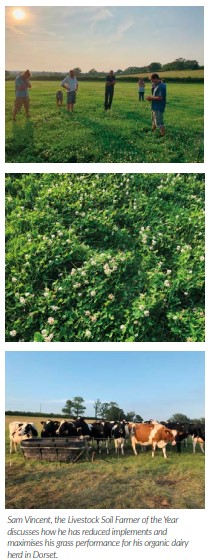

This year’s Livestock Soil Farmer of the Year, Sam Vincent manages his 100 cow dairy farm using 130 hectares of permanent pasture without the need for re-seeding in the past 15 years. Based in Dorset, Sam transitioned his herd to organic in 2018 following the challenge of a TB breakdown, explaining “once our cow numbers were lower and following a couple of years where we had cut our nitrogen back dramatically and seen an increase in grass yields we felt ready to make the jump”. Averaging 5,500 litres per cow, Sam looks to maximise his grazing system to minimise costs. Cutting nitrogen usage from 120kg per hectare to only 35kg and seeing success gave Sam the confidence to make the change to an organic milk contract with Arla as well as becoming a member of the Pasture Fed Livestock Association for cattle sold for beef.

Soils on the farm are variable, and range from higher clay content to more silt based loams. Sam minimises trafficking across his grazing area, avoiding topping and rolling where possible and allowing the cattle to do the work instead – “If you’ve got a rotation, with cattle who are utilising the pasture, then you don’t need to be sat on the tractor”. Sam has seen vast changes not only in his pastures and cattle performance, but equally with his farming approach, explaining “Before we went rushing around, we’ve now got time to stop and think – feel better. We are more resilient and sustainable now”.

The herd calves in late summer in a single block, which in the future Sam hopes to bring earlier on into the season to a May/June timing. Grazing management is critical to Sam’s success with cattle out early March until the end of November. Youngstock are often grazed for longer on fields away from the dairy to optimise nutrient cycling around the grassland area. Any cattle destined for beef are outwintered using a deferred grazing system, shutting off the driest fields on the farm in early summer and lining out bales. He explains. “In the past we were going back and back to the same fields, eating everything and leaving nothing. Now we try to lengthen our rotations as opposed to keeping the grass continually short.” Sam’s approach can be considered as ‘mob grazing’ and he has seen success with this management system with his British Friesian herd, combining his grazing strategy with a small quantity of concentrate feed (6- 800kg) – “We needed a cow that has longevity, and will work on our system”

Sam manages forage quantity and quality through monitoring his grasslands, with previous management practices such as predominantly ryegrass re-seeds altering the clover stand in some fields. He explains “We should have done things a little bit differently, but that’s how you learn”. The milking herd are moved twice daily at 12 hour intervals with back fencing – “We cut fields and graze fields in a rotation rather than continually cutting all the time, the flexibility needs to be there to decide based on grass condition and stocking. The fields at the other end of the farm benefit a lot from the flexibility, the soils are a lot shallower”. Using this system Sam has implemented troughs which are designed to be mobile through the use of a skid, meaning that they can be moved daily with the cattle.

Through monitoring grazing behaviour and milk quality Sam is able to tailor his future management plans on a field by field basis; looking at plant growth stages rather than having a predetermined plan, Sam aims for a 40 day plus field rotation which has previously been highly successful – “increasing the rotation length to 50-60 days, and leaving higher covers we are seeing diversity within the pastures which is as a result of management”. To measure grassland performance Sam currently uses a plate meter and samples the cover and stand regularly, however future developments with satellite measurement is something that he sees being useful.

Transitioning to this management system and reducing fertiliser application rates has seen Sam’s pastures increase in species diversity – “some people think, in order to get diverse leys you need to rip it all up and start again, but that isn’t the case”. Understanding that throughout the grazing season the species available, such as early season foxtail and later vetches and trefoils, will vary helps manage the ground. Sam explains “We have fields that haven’t been reseeded but have still got diversity including trefoil and native red clover.

If you reseed with ryegrass, the species that come back once the ryegrass dies back is weeds, usually annual meadowgrass and other non-productive species”. The flexibility of the grazing system, through cutting silage at a similar height to that at which the cattle would naturally produce maintains this adaptability – “if you have a field that you were going to cut but the weather turns wet then it isn’t the end of the world, you can simply go back and graze it”. The highest risk period like on many farms is often early spring -ground is soft and consequently Sam finds that higher residuals and lower stocking rates help to protect the structural integrity of the soil from poaching.

Regularly weighing cattle helps manage youngstock as they develop. Reared without concentrate on a whole milk diet, Sam finds that separating them into smaller groups when they are turned out they can be easily fed with a 50 teat feeder whilst they begin to graze. Youngstock are managed with a back latch system, being moved once per day onto fresh grass – “if we let the stock graze it then we don’t have to haul the muck out there” adding, “FYM is spread in April on ground which that had been grazed and spread on ground which is cut for silage later after cutting.” Through covering all manure stores, Sam has minimised the need for irrigation of dirty water and installing over 4000 railway sleepers for tracks has increased accessibility across the farmed area. In addition to the cows on farm, Sam also utilises pigs to help compost his FYM in cattle sheds. Through adding corn to the sheds the pigs mix the remaining material over a 6-8 week period.

Having initially experienced a lower yield through minimising concentrate use on farm, Sam has seen the benefits of a lower input system – “Milk from forage percentage is high and milk solids have gone up. Not having inputs makes an impact on the beef/dairy. Organic milk price means that the impact has been minimal. The business is a lot more stable.”

Buckinghamshire farmer Antony Pearce is this year’s Soil Farmer of the Year Runner-Up. Having been inspired to start his journey into regenerative agriculture after reading David Montomery’s book, Antony began to transition away from his existing “safe and conventional system”. The 300 hectares of heavy clay arable ground is run in a split system. Half of the farm is under full “regenerative” management and the remaining 150 hectares in what would be considered a more conventional system, allowing Antony to financially monitor the performance of each approach. He explains “My original reason for looking at a low input system was after some conversations that yields were showing what organic farmers would expect. My 10 year average from the conventional system is 9.1 tonnes per hectare. Comparing the numbers, I was spending £130 per tonne for every additional tonne over organic yields. This seemed like something to focus my attention on”. The true success of any regenerative farming practices trialled on the farm is when a particular approach is also incorporated into the “conventional” proportion of the farm. Through his YouTube channel Antony shares and discusses his journey, highlighting the successes and challenges that he has found throughout his journey.

Focussing on soil health, Antony has gone on to attend Elaine Ingham’s soil health course to realise the importance of the rooting matrix of a plant and the environmental conditions required to access nutrients made available by microbial activity. He explains “Plants are able to secrete 30-40% of their energy through their roots to feed the bacteria and fungi in the soil” adding, “If we are relying on the soil fungi to feed the plants, what negative impact are the fungicides having to this relationship?”. Subsequently, Antony has begun to remove fungicides from his crop protection program, eliminating their use entirely from 150 hectares which is managed in a wholly regenerative manner.

Runner-Up Soil Farmer of the Year, Antony Pearce demonstrates how he has reduced inputs and utilised data to analyse the success of regenerative practices at his farm in Buckinghamshire.

Instead focus is upon genetics and variety to provide a natural resistance to disease pressure. Awareness that the carbon from root exudates is often utilised by microbes following nitrogen application, Antony has also moved to reduce artificial fertiliser application. Having initially relied upon imported organic manures for nutrition, Antony now implements cover cropping as a more cost effective approach, finding benefits of a clover or rape/fenugreek understorey blown into a standing wheat crop for blackgrass suppression – “whether it helps my rape yield is immaterial, I don’t want a carpet of blackgrass!”.

Antony is currently producing oilseed rape using 30kg of nitrogen from digestate and a further 15kg from foliar applications, without any fungicide or insecticide usage. Furthermore, in the previous season Antony had produced a 6.5 tonne a hectare wheat crop on a zero nitrogen system and Elianne oats on a gluten free contract for human consumption using only 15kg of foliar nitrogen and stubble raking to liberate what was already existing in the soil. When conducting nitrogen trials with different products, Antony always leaves a control strip for comparison of the financial and crop data – “there is a need to provide the evidence as to what works on your farm”.

All straw is chopped to help contribute to organic matter and overall soil health, and again using a stubble rake after drilling oilseed rape to help with slug suppression. This can create a rotational challenge for Antony as it hinders his capacity for cover cropping – “It’s a balancing act, if you go for slug control, you need to rake, rake, rake but you then forego your ability to have a cover crop. Sometimes we manage to get cover through the rape volunteers and it fulfils this function at the same time”.

As a farm based on heavy clay soils, there are often challenges with trafficability – but focussing on soil health has started to produce results. Regular applications of compost made from a 50/50 mix of cattle muck and woodchip are a major component of Antony’s management practice. Through applying compost in the 5 years prior to a wheat crop, Antony hypotheses that 200kg of nitrogen should be available for uptake. Improving soil health through composting and cover cropping has also seen benefits in water infiltration and holding capacity, something Antony was keen to maximise following a visit to Gabe Brown in America and seeing the benefits this had.

He explains “back in the winter we had a big crop of mustard, and there was a big rainfall event (around 100ml), the field walked beautifully – it managed to hold onto the water and soak into the soil”. Furthermore, the nature of heavy clay and its predisposition for extreme behaviours such as waterlogging and drought are a constant challenge, but through Antony’s management the rotation has become more flexible – “we can now start to develop a system where we can effectively capture water over the winter through the use of a cover crop which lets the rain work its way into the soil, then I don’t need to worry about spring droughts as the water reserves are there”.

Antony has also begun to integrate livestock into his arable program, grazing sheep on his cover crops before drilling to introduce more organic matter and nutrients back into the soil profile. He explains “Without a doubt we need to leave at least a month between the sheep coming out and us drilling. The soil needs time to recover, the worms need to come up and grab the muck and reintroduce the air into the soil”. Further adding, “We want the sheep to hit is quite hard and move on, which sometimes can take some explaining. We try and design it so the sheep are hitting the mustard stands earlier in the season and then move onto the vetches later”. Alongside the sheep, Antony has also diversified into other opportunities such as sloe gin, turkeys and dog arenas -maintaining future financial as well as soil focused resilience.

The three farm walks demonstrate the vast knowledge, adaptability and versatility of approach to soil management. Our three winners continue to demonstrate their passion for soils and the benefits that maximising the quality and resilience of this biome can provide for their businesses.

The Soil Farmer of the Year competition for 2022 will launch on the 5th of December (World Soils Day). If you are interested in applying or would like to nominate someone who’s work in soil health and farm resilience deserves recognition more information can be found at www.farmcarbontoolkit.org.uk.