Drone technology is poised to bring about a significant transformation in crop research in the coming years, according to leading agronomy company Agrii. This technology has the potential to not only enhance the capacity of plot assessments traditionally conducted by researchers but also to improve the consistency of results across all Agrii trial sites throughout the UK.

Dr Ruth Mann, head of research and development for Agrii, has been looking for disruptive innovation in field research trials for some time. “Assessments are completed in exactly the same way as they were when I was first involved in small plot trials work over 30 years ago. New technologies are providing opportunities to move this approach forward considerably,” says Dr Mann.

Trials depend on researchers to collect in-season data on a range of factors like plant counts and NDVI. Given that most research sites extend to several thousand plots, this process is not only time-consuming and labour-intensive but also prone to subjectivity, leading to potential discrepancies in results among researchers.

Agrii has been actively working with specialists at Drone Ag and heliguyTM to explore the potential of drone technology in their R&D programme. Leading this research is Jonathan Trotter, the technology trials manager at Agrii.

“Agrii operates 40,000 trial plots at sites across the UK,” says Jonathan. “Each of those plots requires different assessments at different times of the year according to the requirements of the trial. This is a huge logistical effort.”

Dr Mann adds: “These assessments are subjective as they are completed by researchers with their innate biases. If we can complete these assessments objectively using software, we can remove any variability among researchers, resulting in data which are comparable across the country. This provides further enhanced technical backup for all products marketed by Agrii.”

Drones will not be able to replace every trial assessment, so Jonathan has focused his work on analysing which are most readily replaced. To do this, he conducted trial assessments using a drone and compared the results with the data collected by a researcher.

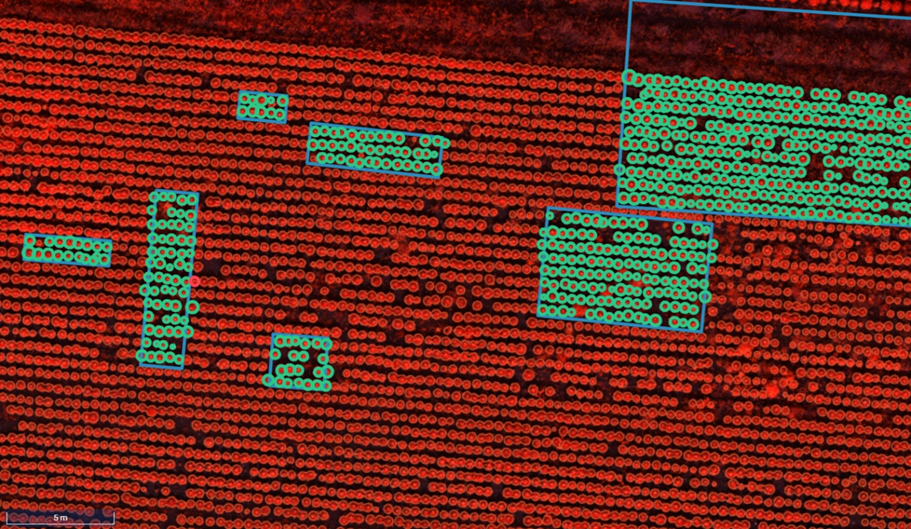

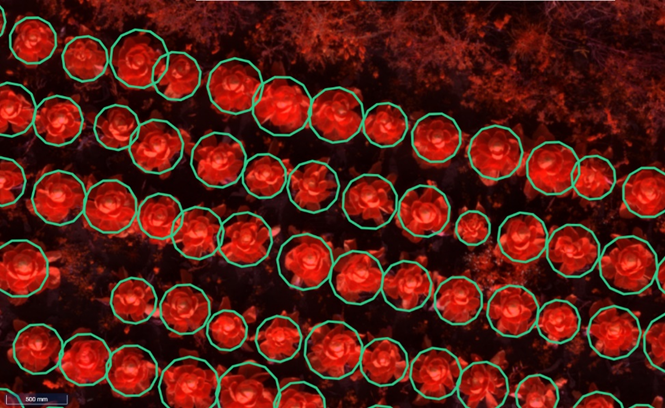

“One example of work that can be replaced by a drone is cabbage plant counts and head sizes. I flew the trial several times with a drone to collect the data and then sent someone out to ground-truth that reading. Most of the time, the drone gave the precise cabbage size; at worst, it was only two centimetres out.

“These data points were gathered using the photogrammetry method. The drone maps the trial with hundreds or thousands of high-resolution images that are stitched together for analysis. The downside is that it requires a lot of data and takes a long time to process,” explains Jonathan.

New drone tech moving things forward

An alternative method uses Drone Ag’s Skippy Scout platform. Currently, this is used to aid agronomy and decision-making in commercial fields rather than R&D. Scout points are identified across a field, and data are collected from them, which helps build a more complete picture for agronomists and farmers. Agrii is collaborating with Drone Ag to use this technology and their A.I. in trial plots.

“Our custom flight control technology allows a drone to take detailed low-level images of each plot,” describes Jack Wrangham, director of DroneAg. “It will speed up the process of assessing trials because there will be no need to stitch together many images like with the photogrammetry method.”

The Skippy Scout system will allow the researcher to assess multiple fixed points per plot. The drone will return to the same point for subsequent assessments. The Skippy Scout method should also allow a greater range of assessments to be conducted by drones.

“Having the drone closer to the plot gives much more detail to the imagery. Photogrammetry is very good for detecting differences between plots, but it still requires ground-truthing by a person to analyse what the difference is attributed to. The Skippy Scout system does 95% of this.

“It should reduce much of the labour required to run trials and can help target where a researcher needs to check a trial by flagging specific plots that would benefit from checking,” adds Jack.

Fully automated flight on the horizon

The game-changing development for using drones in R & D will be if they become fully automated. This would enable drones to conduct many more assessments than has ever been possible, all carried out on a fixed schedule without needing a human to be present at the trial site.

“In a fungicide trial, we currently do disease assessments perhaps three times in the critical spring period,” says Jonathan. “If you really wanted to, you could fly every hour of every day to detect things we are currently missing.”

The technology is capable of unmanned and beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) operations, but current UK regulation restricts its use. Agrii is working with heliguyTM, a leading drone retailer, consultancy and training provider, to help build the case for BVLOS use.

“At the minute, the regulation is pretty limited in the UK,” says Mark Blaney, head of training at leading drone retailer and training provider Heliguy. “Recently, the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) has announced a ‘regulatory sandbox’. They have appealed for stakeholders to come forward to participate in a trial test of their proposed regulation to allow BVLOS.

“Companies will have to build up a use case with evidence of safe automated drone use to get authorisation from the CAA, which Agrii has been doing with their existing work.”

“Bringing together the skill sets in these three companies will lead to long-awaited innovation in field trials. Enhancing data collection methods beyond traditional photogrammetry techniques by using the advanced analytics of Skippy Scout and combining this with full autonomy will increase the value of the trials Agrii complete across the UK and reduce the monotonous field assessments that need to be completed by highly qualified researchers,” concludes Dr Mann.