This article was “Written by Camilla Hayselden-Ashby, Nuffield Scholar 2021

Hemp, Cannabis with a low level of the psychoactive compound THC (tetrahydrocannabinol), has seen a global upsurge in interest in the last decade. This has been driven by the growing popularity of CBD as a food supplement, demand for environmentally sustainable products and changes in legislation around cannabis growing. The global hemp market is projected to reach $15.26 billion by 2027.

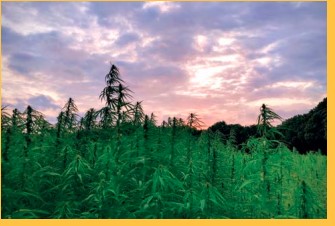

This growth in the demand for the crop is generating interest among UK farmers. Although the area cultivated in the UK is small (820ha in 2020 according to the BHA), hemp has huge potential as a financially and environmentally sustainable break crop. This could not come at a better time as farmers look to diversify in the transition from BPS, and reduce their carbon footprint. The UK has a long history of hemp cultivation starting from Roman times, and it was an economically significant crop until the start of the 20th Century. For much of this time, it was such an economically important crop for rope and sails in the shipbuilding trade that there were subsidies available to encourage farmers to grow it. Under Henry VIII it was even required that every farm grow a quarter of an acre of hemp for every 60ac cultivated. Hemp has over 25,000 uses, with applications for all parts of the plant. These include food, construction, textiles and bioplastics.

It is also environmentally beneficial to grow. Hemp produces a lot of biomass in a short period of time, allowing it to sequester an estimated 15t of CO2 per hectare. This makes it an important tool in the race to Net Zero. Its deep root system (the taproot can go down to 2m) improves soil structure and brings up nutrients from lower in the soil profile. It has low input requirements and reduces herbicide requirements thanks to effective weed shading. Finally it takes up heavy metals in the soil, enabling its use in phytoremediation to deal with soil pollution.

Markets

There are three key parts of the hemp plant which can be harvested; seed, stem material and flower.

Flower

CBD, extracted from hemp flowers, has seen a boom in popularity in recent years and is taken for anxiety, inflammation and pain relief. This is a high-value output, but UK farmers will have to wait to take advantage as current industrial hemp licensing prohibits processing of flower and leaf material. As a result, the CBD oil sold in the UK is all imported. In the Channel Isles this restriction has been lifted, allowing farmers such as Jersey Hemp to tap into this growth market.

Seed

Hemp seed is the easiest market for cereal growers to switch to since it can be harvested using a combine harvester. Seed varieties are usually shorter at 1.5-2m (vs. 2-4m for other varieties). Finola is popular among UK growers because it has been bred to flower automatically 120 days after sowing, rather than being triggered by a change in day length; this allows an earlier harvest in mid-September. Hemp seed is nutritionally dense with high levels of omega oils and protein. It is pressed for oil, made into hemp milk, sold as whole hemp hearts which can be added to cereal or smoothies, and processed into protein isolate used in vegan meat-alternatives. Hemp oil can be extracted using cold press equipment similar to that used for oilseed rape. There are also several UK companies who produce hemp oil and seed products such as Good Hemp.

Stem

Hemp stem consists of long outer bast fibres and a woody core which is broken up into ‘shiv’. These are separated through a process called ‘retting’ allowing the plant to break down slightly in the field followed by decortication which uses physical processes to separate the fibre and shiv. These products are used for construction, animal bedding, paper, kindling, bioplastics and textiles.

Building

Hemp is used to make ‘hempcrete’ a more sustainable alternative to concrete, made by mixing hemp shiv with lime. This results in a construction material used in walls with a timber frame or sprayed for insulation. As well as the carbon sequestered while the plant grows hempcrete buildings lock up additional carbon as they cure with total carbon sequestration potential of up to 300kg of CO2 per m3 . Hempcrete provides good sound and heat insulation, is not flammable and is breathable.

Plastics

Hemp fibres can be combined with resins to produce biocomposites as a more sustainable alternative to traditional plastics. Hemp composites are used in a wide range of products. Car door panels are the most common, in fact the body of the original Ford Model T was made of hemp, but it is also used in packaging, sports equipment, furniture and musical equipment.

Textiles

Hemp fabrics are one of the most traditional uses of hemp fibre. They offer a natural, sustainable alternative to the polyester used in most of our clothing or cotton, production of which often uses large amounts of pesticides and water. It produces fabrics similar to linen but innovators are experimenting with blends and even using it to make an alternative to synthetic fake fur.

How to grow

Grows like a weed’ is particularly apt when talking about hemp. It grows even on poor land and has low input requirements with no pesticides and little fertilizer. However getting the best out of it requires some care, particularly at establishment.

Drilling

Hemp is a spring crop and is planted from April through to ate-May. It grows best in well drained soils with good fertility and organic matter. Soil temperatures should be above 10oC for planting and it is important to have some moisture for it to get going. As hemp is a small seed, establishing good seed-soil contact is essential. It is also quite particular about drilling depth with a target depth of 3-4 cm. It is possible to establish by direct drilling although most growers cultivate prior to drilling to ensure a fine seed bed. Seed rates should be around 30-50kg/ha. Hemp needs Nitrogen at the start to get going. 60kg/ha should suffice although yield improvements are seen up to 150kg/ha.

In season

Seedlings take about 5-7 days to emerge and are quite vulnerable to birds and weed competition at this stage. However once the crop gets away it will easily outcompete most weeds as it grows so tall and dense that it will shade them out. After this it is a bit of a case of ‘shut the gate and wait’. Pests and disease are not usually too much of a problem. There is the potential for fungal disease of the flowers such as septoria or white mould but these have yet to present a significant issue for UK growers.

Harvest

Harvesting hemp can be challenging as its tough stems and long, strong fibres can wear down and wrap around machinery. While there is specialised harvesting equipment available this is not yet cost effective for the UK scale of growing. Most UK growers use conventional arable equipment or have built their own solutions to deal with the crop.

Harvest timing depends on end use.

Hemp seed is ready from mid-September. The seed can be cut using a conventional combine. It is important to set the cutter bar as high as possible to minimise the chance of the strong fibre wrapping around the machine. It is important to have immediate access to drying facilities to dry the crop to 9% moisture, particularly as it will normally be harvested quite green to minimise seed loss and fibre wrapping. Potential yields are 0.8-1.2t/ha. If harvesting for fibre the optimal time to harvest for quality is at full flowering in July. The stems can be cut using a sickle mower, ideally at several heights to produce lengths of approximately 60cm which is preferred by fibre processors. This is then left in the field for several weeks to field ret, where the combination of microbes from the soil and moisture from dew break down the bonds between the hemp fibres. This is then baled and taken to be decorticated. Typical yields are 6-12t/ha.

There is potential for ‘dual-cropping’ where the straw left standing after seed harvest is cut, retted and baled. This is popular in Europe but is difficult to achieve at UK latitudes since the seed is harvested so late that it is often too wet to ret and bale the straw. An alternative approach is to leave the stalks standing over winter to ‘stand ret’ and then cut and bale in the spring. However this can negatively impact stem quality.

What are the challenges?

Despite the benefits hemp offers as a crop, there are a number of challenges facing UK growers.

Licensing

In the UK growing Industrial Hemp requires a license, administered by the Home Office Drugs and Firearms Licensing Department. Applications open in January and it is advisable to allow at least a month for processing (although it can take longer). As part of the license application you will have to supply a DBS (Criminal Record) check, state where you plan on growing it, which variety you plan to grow, the target end market and how you will destroy the flowers and leaves. Your selected variety must be one from the approved list of strains with THC levels of less than 0.2%. Growing locations can also pose a challenge as it is required that the crop is grown out of sight, away from roads, footpaths and houses.

Access to suitable varieties and agronomic

knowledge

The relatively small area grown means that there is a lack of experience growing the crop and there have been few crop trials to test varieties and growing methods for the UK climate. In addition the current approved variety list is inherited from the EU variety list which means that most of the options included are suited to more southern latitudes. Breeding and trial work is needed to establish varieties suited to UK growing.

Processing facilities

There are only three decortication facilities in the UK which is a barrier to the fibre industry taking off as it means that growers have to transport bulky straw bales a long way for processing. For hemp growing for fibre to become more mainstream we need to establish regional processing capabilities such as mobile decorticators or regional processing hubs (as is seen in France). The global prohibition of hemp means that harvesting and processing equipment development is behind that seen in other mainstream crops although progress is being made rapidly as hemp gains popularity.

Market access

Most of the markets for hemp are still developing. This means that growers will need to put in more work to find a buyer for their crop or do their own processing. Finding the solution to these challenges inspired me to apply for a Nuffield Scholarship. I will be using my 2021 Nuffield Scholarship, kindly supported by NFU Mutual Charitable Trust, to see how the UK’s nascent hemp industry can learn from international best practice in countries such as Canada, the USA, China, France, Germany, Holland, Ukraine and Romania. Anyone with experience of or an interest in growing hemp in the UK or abroad is very welcome to get in touch at chayseldenashby@gmail.com.

Fact box

• The global hemp sector is projected to be worth $15.26 billion by 2027

• 820ha currently grown in the UK vs 150,000ha globally

• Uses in food, construction, biocomposites, textiles and pharmaceuticals

• Strong potential as a tool for carbon capture, sequesters CO2 at 15t/ha

• Drilled in April-May and harvested in July-September depending on end use

• Growing in the UK requires a Home Office licence

• Processing of flowers and leaves for CBD is prohibited

Hemp on our farm

I was inspired to start growing hemp on my family’s farm in Kent after learning about the huge number of uses it has which convinced me that it would have a key role to play as a crop for a sustainable future. As I write I look forward to the harvest of our first trial crop in a few weeks time with excitement and not a little trepidation. We are growing a dual-use variety called Ferimon to be harvested primarily for seed. For this year’s crop we have experimented with growing with zero inputs to see what the baseline potential is. We have still managed to get a decent crop with 2.5m plants in the best parts. The field was drilled with a Claydon Hybrid following on from a cover crop of rape, mustard, radish and turnips which was grazed off with sheep.

We are also participating in an Innovative Farmers Field Lab to monitor the impact of growing hemp on soil health and biodiversity. For this we are taking soil samples, including organic matter analysis, and measuring insect numbers before and after the crop as well as in a control field for two growing seasons. My hope is that this will provide additional evidence for the government to relax hemp regulation so that more farmers can grow it.