Labour shortages are driving fruit and veg producers to examine robotic solutions. Tech Farmer attends the World Agri-Tech Innovation Summit in London to find out more.

Increasingly difficult to find and ever more costly. It’s little wonder that some of the UK’s most innovative farms and businesses are choosing to investigate and invest in the potential of robotics, rather than relying solely on manual labour.

“The reality is that it has become increasingly challenging to source seasonal labour in the UK,” says David Sanclement, Group chief executive officer of The Summer Berry Company.

The firm grows strawberries, blueberries, blackberries and raspberries across 200ha in the UK, including 24ha in glasshouses, and mostly raspberries on 190ha in Portugal. “Our core market is the UK, and we serve most of the major retailers, including Tesco, Marks and Spencer, Waitrose and Asda. We also supply European retailers like Carrefour, Rewe and Aldi.”

With no immediate prospect of the labour market becoming easier, the business has a vision to reduce its dependence on seasonal labour. Robotics is one area it is investigating, although David stresses he doesn’t see robotics as a complete replacement for labour.

“It could be useful in a number of situations,” he explains. “Most notably, using robots to forecast and potentially to provide a night shift, which is currently not attainable for our workers.

“In the longer term, we hope the use of robotics will support our labour needs eventually meaning less seasonal workers. It would be more efficient to have a stable year-round workforce with the robots supporting at peaks of harvest.”

Another important advantage for the use of robots is through better forecasting capabilities, David adds. “This is important to us. We work with historical trends, relying on the expertise of our agronomists and weather forecasts, but with the addition of data coming from the robots we have better forecasting accuracy of when to pick.”

Improved harvest data forecasting brings a couple of advantages for the business, David says. “One, it gives us an opportunity to forecast our labour more efficiently. If you can predict very accurately when you’ll need to harvest the fruit, the difference between one week and another, you can optimise your labour in a better way.

“And two, you might achieve better returns with the supermarket. A retailer will be keen to receive information three weeks ahead rather than two days because it gives them a better opportunity to plan promotions or to plan strategically to allocate your fruit onto the shelf.”

The Summer Berry Company trials with robotics start-up Tortuga AgTech began in 2018, with pick quality and picking speed the two most important criteria success was going to be judged on.

“This is a journey,” David says.

The business started comparing robots to the best picking performance but quickly realised it should be comparing them to the poorest picking performance. “AI and software are constantly improving, so you need to start from the bottom and progressively raise standards.”

Picking speed has also improved significantly over the past three years, although generally it is still not as good as human labour. That doesn’t matter that much with David looking at his current 54 Tortuga AgTech robots to replace night shifts or tackle fields where labour is not available.

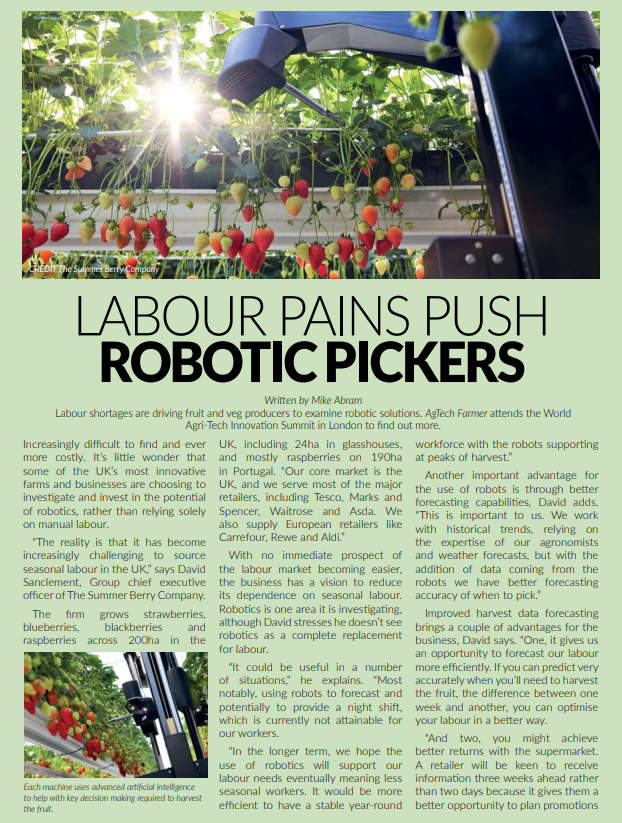

The purpose-built and designed robots are cart-sized four-wheel machines that can work either inside or outside, with two arms that operate autonomously, explains Tortuga AgTech chief executive officer and co-founder Eric Adamson.

Each machine uses advanced artificial intelligence to help with key decision making required to harvest the fruit. “The most important thing you teach a human picker on their first day is which fruit to pick and which to leave,” Eric says.

“Most of the management time after that is whether the workers are doing that right? Are they picking red ones and not the pink ones, or are they picking the pink ones that look red enough? That’s actually losing yield for the farm and it’s not as good quality for the supermarket.

“Team leaders at The Summer Berry Company focus on performance, quality and speed. We need the same focus with the robots.”

The robots run 17 machine learning models at any given time to help make those sophisticated decisions – where and how to drive, where and what to pick, and whether to pick or not. It’s also collecting a bunch of data about the crop’s growth at the same time, Eric says.

While the latter is an important add-on service, Eric stresses that providing a harvesting service first was key as it creates immediate value for the grower. “Help to solve the hardest problem first and then add the other things.”

Customer service is another key requirement. “We provide a full service to the farm,” Eric says.

That was important and a significant change, David adds. “I’ve worked with some other companies doing robotics and not all of them were able to offer service. Having a number of Tortuga members working at The Summer Berry Company makes a big difference if the robot is not working.”

Barfoots target automation

High value vegetable crops are also fundamentally labour intensive making them a logical target for automation, says Keston Williams, chief operating officer of Barfoots. But some are much easier than others to automate.

His firm grows around 3400ha of various vegetable crops in the UK. “The vast majority of the area is sweetcorn, followed by tenderstem broccoli, courgettes, asparagus and green beans.”

Like other farm businesses in vegetable and fruit production, accessing labour has become more challenging following Brexit. “I don’t see that getting any better any time soon, and it’s certainly continued to get more and more expensive, so we’re looking for solutions that allow us to reduce labour and improve efficiency.”

In some crops, such as sweetcorn and green beans a fully automated system for the crop is in place, in terms of machines for harvesting, grading and packing.

“In green beans we’ve taken it from a team of what would now be 400 people harvesting green beans to a team of 12 because it’s automated.

“But for the sustainability of growing UK premium veg crops, we need to consider how we’re going to automate the majority of our crops.”

But what makes a crop like sweetcorn relatively straightforward to automate – it’s a single destruct harvested crop – is the exact opposite for crops like courgettes and tenderstem broccoli.

“With courgettes we have to go into the field maybe as many as 25 times to harvest or graze it over a period of time. It’s not a destructive harvesting process, so therefore you need to look after the crop when you harvest. Tenderstem broccoli, rhubarb and asparagus are the same – multiple passes of the same crop.

“Secondly, you also need the dexterity that’s required to pick the crop – see the fruit, or flower in the case of tenderstem broccoli, and then pick it at the right point.”

The image processing involved in that to decide on the spot whether to harvest now or leave it for another two days to mature, or if then it will be over mature, plus then the dexterity to pick it and put it in the right container are decisions the human brain can make quickly and with great accuracy. “They’re much more difficult to replicate on a robotic basis.”

For a while Barfoots put those requirements in the too difficult to overcome box, but advances in artificial intelligence and image recognition have brought it into the realm of the possible, Keston suggests.

That’s led to three projects beginning with tenderstem broccoli in 2020, then courgettes two years ago and a herd project last year with robotic company Muddy Machines using funding from UKRI and Innovate UK.

The initial project with tenderstem broccoli started by testing image recognition, Keston says. “That’s grabbing a camera, pointing it at the crop, move it around and then develop software that can recognise it. As long as you can get around and through the leaves, it doesn’t work too badly.”

The next phase was to develop a robot, or “end-effector” as Keston calls it, that can harvest the crop. This came in two parts – first Muddy Machines developed a lightweight robot platform, called Sprout. Sprout is then fitted with bespoke tools under the canopy.

“The piece of kit we designed gently pushes the leaves out of the way, and then another arm enters the crop and picks the tenderstem broccoli,” Keston says.

“We’ve developed it as a proof of concept, but we’ve reached the project’s end point where it’s proven to be difficult and slow. At the moment, the project is parked because to scale it up and make it work is going to be extraordinarily difficult.”

Courgettes are looking more promising. “We’ve got a stage where we can recognise the courgettes, and have developed a little end effector that can pick them without damaging the main plant.

“The project is reaching its conclusion now, and it is looking more exciting to take forward to the next stage of developing an initial prototype, although I would imagine there would be multiple prototypes before it comes anywhere near being commercially viable.”

Five growers, including Barfoots, are involved in the latest “herd” project. The concept is having a harvest team of one person, who controls maybe 20 harvesting robots or rovers, which coordinate harvesting of the crop from one press of a button.

“It’s about having some sort of centralised coordination of multiple robots that logically think like a harvest manager.”

While the projects are showing the challenges of automating harvesting and processing of some crops, Keston believes it is also highlighting it is achievable. But lack of investment is slowing down progress.

“As an industry, it’s being done on a shoestring. It’s not like you have a backing of a Tesla or some huge industrial process that’s shoving millions at it to get it right. These are literally garages of clever guys making stuff, and because of that I think it will take time to get there.

“But it doesn’t have to. The proof of concept shows it is possible, it’s just the development and the engineering around it that needs to accelerate quickly and that funding needs to come from somewhere.”

Unfortunately, he says the profit margins within fresh produce aren’t enough for businesses like Barfoots to fund that development, while there isn’t enough volume in the number of robots required for a machinery business to get excited.

“As a consequence it’s languishing in a horrible midfield area that doesn’t go anywhere. I don’t have the answer of how that can change unless a philanthropic entrepreneur wants to give it a go,” he concludes.

- The World Agri-Tech Innovation Summit took place in London on September 26 and 27, 2023.

Asparagus harvesting tool showing promise

An asparagus harvesting tool to fit onto Muddy Machines robotic platform, Sprout, is showing potential to be the viable application that unlocks further development uses, says Chris Chavasse, founder and chief technological officer of Muddy Machines.

Muddy Machines developed Sprout as a fully electric platform, with a 16 KwH battery that can run for 12-16 hours depending on the tool inside its payload. It’s a 1.8m wide x 1.8m long 350kg platform without a tool – four easily accessible crop storage baskets hang off the back with the tools fitting under the canopy.

“It’s four-wheel drive, rear-wheel steering, and has a pivoting front axle to maintain contact with the ground,” Chris says. “It drives up to 1 metre/second so relatively slow – that’s about 5km/h, but it’s much slower than that as it has to stop and start to identify where the crop is.”

It’s currently slower than a person picking asparagus, which is the first tool that was developed to fit onto sprout. “We’ve been developing it for the past three seasons. It uses 3D cameras to identify where the crop is, machine learning to identify when we want to harvest, what’s right, what’s not and avoid all the crop that is immature and only harvest when it is right.”

Muddy Machines hopes to offer Sprout as a platform to other innovators or companies on which to develop their own tools, Chris says. “We are proving the platform is a viable solution, so we hope it gives confidence for others to use to develop their own tools so they can get those solutions to growers faster.

“When we started there wasn’t any suitable platform so we had to develop our own. It’s been hard so we don’t want others to have to go through that pain and slow them down.”

The machines have been developed so one person can supervise five to 10 robots, and because they are modular with capability of carrying different tools it allows maximum utilisation without large capital investments for growers.

Muddy Machines currently offers the robots on a harvest-as-a-service model, where it operates the robots and gets paid in the same way as a human worker would be, but it wants to transition to a hardware-as-a-service leasing model in future, Chris says.

“Growers would say they need the equivalent of 50 or 100 workers, we would calculate and provide the equivalent number of robots. The grower would pay us the equivalent they would pay for the workers.”

Three-Terry tech

Why have four wheels when three offer more flexibility and stability? The 250kg E-Terry from Germany can adapt to range of widths, can be set to different heights to suit crop growth stage and easily folds for transport and storage, says COO and co-founder Fabian Rösler.

Electrically driven and primarily for weed-scouting, it has a forward speed of 1.5km/h and covers 3ha on a full battery charge in eight hours. Pilot trials on five farms in Germany are set to start in the spring.

Rootwave goodbye to weeds

The first 15 commercial Rootwave machines are being delivered to vineyards and orchards over the next few months, says CEO Andrew Diprose.

Available as a 1.8m trailed machine for vineyards or 4m for orchards, a PTO-powered generator packs 10kW of power down to each of six 0.5m-wide electrodes. With a forward speed of 5km/h, the 18kHz high-frequency voltage fries any weeds they come into contact with.

Claimed to be as effective as glyphosate, two-thirds of prospective customers are conventional growers looking to move away from herbicides.