By Brian O’Connor originally published by No-Till Farming

Wisconsin no-till dairyman Chris Conley thwarts heavy rain and hills with no-till, covers and planting green.

No-tiller Chris Conley took two big steps where other farmers might take one.

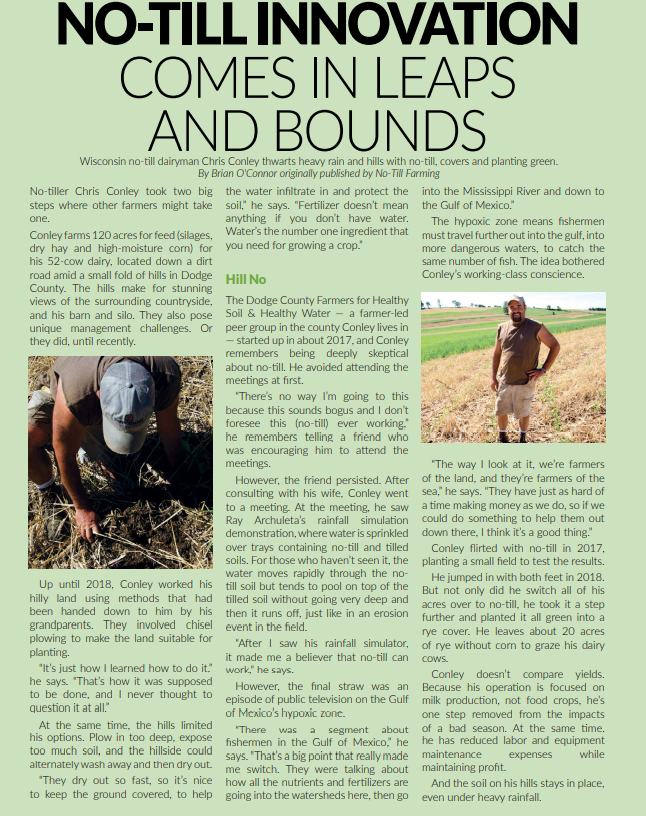

Conley farms 120 acres for feed (silages, dry hay and high-moisture corn) for his 52-cow dairy, located down a dirt road amid a small fold of hills in Dodge County. The hills make for stunning views of the surrounding countryside, and his barn and silo. They also pose unique management challenges. Or they did, until recently.

Up until 2018, Conley worked his hilly land using methods that had been handed down to him by his grandparents. They involved chisel plowing to make the land suitable for planting.

“It’s just how I learned how to do it,” he says. “That’s how it was supposed to be done, and I never thought to question it at all.”

At the same time, the hills limited his options. Plow in too deep, expose too much soil, and the hillside could alternately wash away and then dry out.

“They dry out so fast, so it’s nice to keep the ground covered, to help the water infiltrate in and protect the soil,” he says. “Fertilizer doesn’t mean anything if you don’t have water. Water’s the number one ingredient that you need for growing a crop.”

He couldn’t see No-till would work

The Dodge County Farmers for Healthy Soil & Healthy Water — a farmer-led peer group in the county Conley lives in — started up in about 2017, and Conley remembers being deeply skeptical about no-till. He avoided attending the meetings at first.

“There’s no way I’m going to this because this sounds bogus and I don’t foresee this (no-till) ever working,” he remembers telling a friend who was encouraging him to attend the meetings.

However, the friend persisted. After consulting with his wife, Conley went to a meeting. At the meeting, he saw Ray Archuleta’s rainfall simulation demonstration, where water is sprinkled over trays containing no-till and tilled soils. For those who haven’t seen it, the water moves rapidly through the no-till soil but tends to pool on top of the tilled soil without going very deep and then it runs off, just like in an erosion event in the field.

“After I saw his rainfall simulator, it made me a believer that no-till can work,” he says.

However, the final straw was an episode of public television on the Gulf of Mexico’s hypoxic zone.

“There was a segment about fishermen in the Gulf of Mexico,” he says. “That’s a big point that really made me switch. They were talking about how all the nutrients and fertilizers are going into the watersheds here, then go into the Mississippi River and down to the Gulf of Mexico.”

Farm watercourse pollution was the deciding factor

The hypoxic zone means fishermen must travel further out into the gulf, into more dangerous waters, to catch the same number of fish. The idea bothered Conley’s working-class conscience.

“The way I look at it, we’re farmers of the land, and they’re farmers of the sea,” he says. “They have just as hard of a time making money as we do, so if we could do something to help them out down there, I think it’s a good thing.”

Conley flirted with no-till in 2017, planting a small field to test the results.

He jumped in with both feet in 2018. But not only did he switch all of his acres over to no-till, he took it a step further and planted it all green into a rye cover. He leaves about 20 acres of rye without corn to graze his dairy cows.

Conley doesn’t compare yields. Because his operation is focused on milk production, not food crops, he’s one step removed from the impacts of a bad season. At the same time, he has reduced labor and equipment maintenance expenses while maintaining profit.

And the soil on his hills stays in place, even under heavy rainfall.

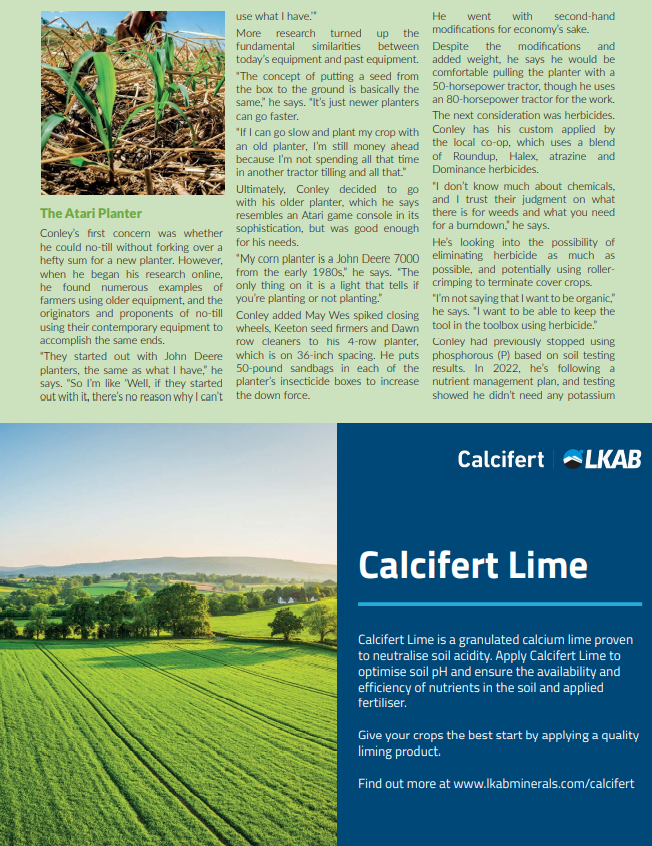

The Atari Planter

Conley’s first concern was whether he could no-till without forking over a hefty sum for a new planter. However, when he began his research online, he found numerous examples of farmers using older equipment, and the originators and proponents of no-till using their contemporary equipment to accomplish the same ends.

“They started out with John Deere planters, the same as what I have,” he says. “So I’m like ‘Well, if they started out with it, there’s no reason why I can’t use what I have.’”

More research turned up the fundamental similarities between today’s equipment and past equipment.

“The concept of putting a seed from the box to the ground is basically the same,” he says. “It’s just newer planters can go faster.

“If I can go slow and plant my crop with an old planter, I’m still money ahead because I’m not spending all that time in another tractor tilling and all that.”

Ultimately, Conley decided to go with his older planter, which he says resembles an Atari game console in its sophistication, but was good enough for his needs.

“My corn planter is a John Deere 7000 from the early 1980s,” he says. “The only thing on it is a light that tells if you’re planting or not planting.”

Conley added May Wes spiked closing wheels, Keeton seed firmers and Dawn row cleaners to his 4-row planter, which is on 36-inch spacing. He puts 50-pound sandbags in each of the planter’s insecticide boxes to increase the down force.

He went with second-hand modifications for economy’s sake.

Despite the modifications and added weight, he says he would be comfortable pulling the planter with a 50-horsepower tractor, though he uses an 80-horsepower tractor for the work.

The next consideration was herbicides. Conley has his custom applied by the local co-op, which uses a blend of Roundup, Halex, atrazine and Dominance herbicides.

“I don’t know much about chemicals, and I trust their judgment on what there is for weeds and what you need for a burndown,” he says.

He’s looking into the possibility of eliminating herbicide as much as possible, and potentially using roller-crimping to terminate cover crops.

Planting green

“I’m not saying that I want to be organic,” he says. “I want to be able to keep the tool in the toolbox using herbicide.”

Conley had previously stopped using phosphorous (P) based on soil testing results. In 2022, he’s following a nutrient management plan, and testing showed he didn’t need any potassium (K), either.

Currently Conley uses 100 pounds of urea and 50 pounds of AMS with his planter. The starter nutrients are placed 4 inches away from the seed trench because he doesn’t have no-till fertilizer coulters. He broadcasts an additional 100 pounds of urea at the V5 growth stage, and continuously applies manure from his cows throughout the season.

For his planting green plans, in the third week of May he typically plants corn at a rate of 34,500 seeds per acre into a stand of living rye that had been seeded at a rate of 60 pounds per acre in October (though he has planted as late as Christmas Eve). He bumped the rate up to 100 pounds per acre in 2022.

He terminates his rye cover after planting.

While he’s used to the practices now, Conley admits no-till and planting green caused nerves as he launched his new methods.

“When I started this, there were a lot of sleepless nights. I thought ‘This is totally not supposed to be working,’” he says. “It was so weird. It was one of the most uncomfortable things I think I’ve ever done farming. But now I do it, I’m like ‘Oh, whatever.’ It’s normal.”

Observations

The Sand County Foundation installed two solar-powered soil probes in his rye field as part of a wider look at soil conditions in various tillage methods. When fall rolled around, Sand County officials reached out to get the probes removed, and Conley asked that they stay in place.

“I had talked to them and finally got them to keep them in because I felt that they were missing a crucial time of the year, over wintertime into spring, of seeing what the water cycle is,” he says.

That data will become especially important as winters become warmer.

The results of the study haven’t yet been released. Conley says he’s seen some data that validates his management decisions, such as more beneficial soil temperatures under cover crops.

“I’ve taken temperatures between two different types of soil — covered and uncovered — this spring, when the air temperature was 95 degrees,” he says. “The uncovered soil was 90 degrees and my soil underneath the manure and cover crop rye was 70 degrees.”

Those 20 degrees can be the difference between heat-sterilized biologically dead soil and biologically active soil in the summer months, Conley says and water infiltration has also improved.

Rain Man

Another data point came in torrents.

Heavy rains swept through southern Wisconsin on the afternoon of June 16, 2022, forcing motorists to temporarily shelter on the sides of Interstate highways. Flash flood warnings were issued for large parts of Dodge County, and other nearby counties.

At the hilly, scenic Conley farm, the rain gauge recorded more than 6.5 inches of rain. Nearby Hartford recorded 3 inches of rain that day, according to National Weather Service Records.

After the rain stopped, Conley and his daughter Mckayla went out to check whether the heavy rains had moved his crops. He saw some movement, but not from his plants.

“The other night, when we got that heavy rain, after we were done in the barn, me and Mckayla were looking out in the field,” he says. “There were millions of earthworms out there. When you took the flashlight, you could see the ground move.”

On a walking tour the next day, corn plants nestled in among heavy straw from his rye covers. On the small paths and headlands, where patches of some soil were visible, heavy rains had carved inch-deep canyons into exposed mud. The soil under the straw — and under a layer of manure below that — was damp but hadn’t moved.

“It’s looking good, I think,” he says, digging through residue. “How much better can you have soil covered than this?”