Wye oh Wye…?

The River Wye intertwines the border of England and-Wales. Once the nations “favourite” river it now probably has more designations than actual fish and continues to regularly feature in the media as the poster girl for agricultural pollution. In this article I hope to provide some insights in the complexities behind the headlines.

Why the Wye? It is designated as a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), it contains an Area of Outstanding National Beauty (AONB), Nitrate Vulnerable Zones (NVZ) and Drinking Water Safeguarding Zones (DWSQZ) yet none of these protections have prevented its deterioration. SAC rivers have to meet tighter water quality targets to, in theory, protect their sensitive and rare ecology. So the Wye along with about fourteen other SAC rivers in the UK are trying to metaphorically tighten their belts much more than others.

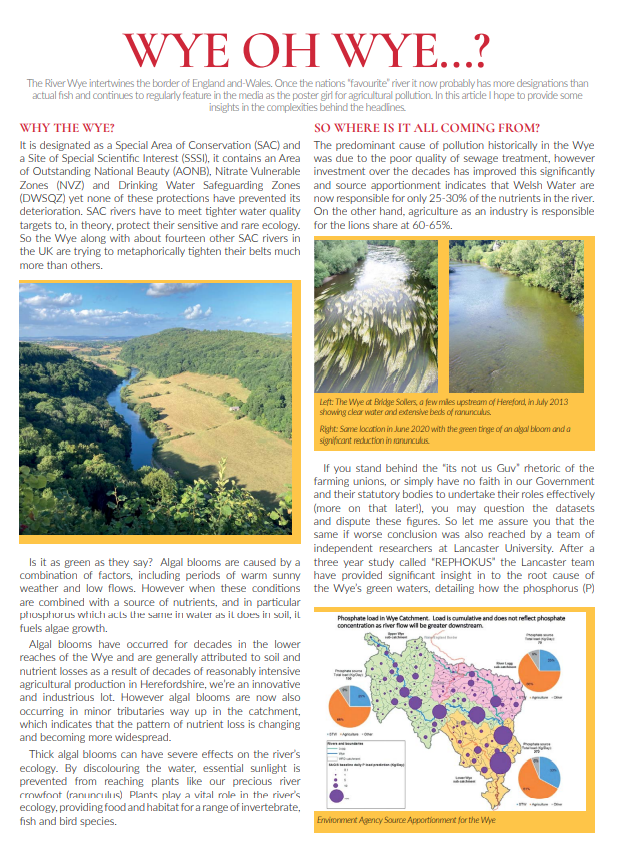

Is it as green as they say? Algal blooms are caused by a combination of factors, including periods of warm sunny weather and low flows. However when these conditions are combined with a source of nutrients, and in particular phosphorus which acts the same in water as it does in soil, it fuels algae growth.

Algal blooms have occurred for decades in the lower reaches of the Wye and are generally attributed to soil and nutrient losses as a result of decades of reasonably intensive agricultural production in Herefordshire, we’re an innovative and industrious lot. However algal blooms are now also occurring in minor tributaries way up in the catchment, which indicates that the pattern of nutrient loss is changing and becoming more widespread.

Thick algal blooms can have severe effects on the river’s ecology. By discolouring the water, essential sunlight is prevented from reaching plants like our precious river crowfoot (ranunculus). Plants play a vital role in the river’s ecology, providing food and habitat for a range of invertebrate, fish and bird species.

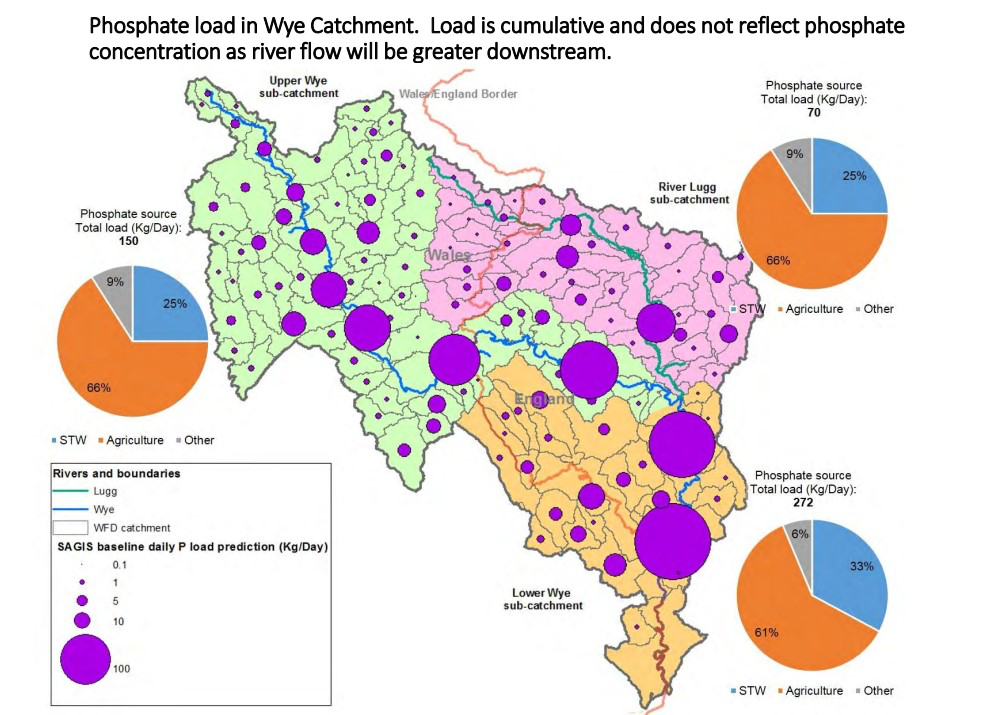

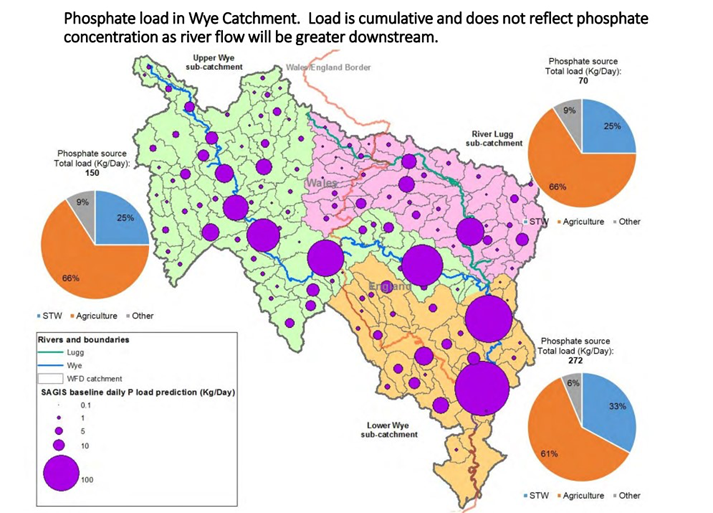

So where is it all coming from? The predominant cause of pollution historically in the Wye was due to the poor quality of sewage treatment, however investment over the decades has improved this significantly and source apportionment indicates that Welsh Water are now responsible for only 25-30% of the nutrients in the river. On the other hand, agriculture as an industry is responsible for the lions share at 60-65%.

If you stand behind the “its not us Guv” rhetoric of the farming unions, or simply have no faith in our Government and their statutory bodies to undertake their roles effectively (more on that later!), you may question the datasets and dispute these figures. So let me assure you that the same if worse conclusion was also reached by a team of independent researchers at Lancaster University. After a three year study called “REPHOKUS” the Lancaster team have provided significant insight in to the root cause of the Wye’s green waters, detailing how the phosphorus (P) burden in the catchment accumulates and how losses are compounded by our circumstances. Their conclusion was that agriculture accounted for 70% of the P load and that we were accumulating an excess of approximately 3000t of P every year in the Wye.

Why all the chat about chickens? The REPHOKUS project identified the largest import of P into the catchment as livestock feed (ca. 5000 t P/ yr), nearly 80% of this is attributed to poultry sector, then 18% to cattle and sheep, and 2% to pigs. Fertiliser P imports to the catchment are just over 1000 t yr. From Sun Valley in the 1960s, to Cargill and subsequently Avara, Herefordshire has long been a major producer of broiler chicken. And with the move from cages, a significant number of free range sites have been established to keep up with consumer demand. We are indeed, for want of a better word, a hotspot. The figures thrown around are 20million birds, but no one yet has been able or willing to calculate the exact number. The fact that its chickens we have a lot of is neither here nor there; a lot of anything isn’t good for you.

I alluded to compounding circumstances earlier; the Wye soils are predominantly sandy and silty so are less able to hold on to nutrients, they are “leaky”. And despite what I was taught, P can be lost in solution like N. Once the soils capacity to hold nutrients is exceeded, which for much of the Wye soils appears to be anything above a P Index of 2, it can be lost in soil pore water and starts coming out in the drains. And having an excess of 3000t P every year for quite some time means that we have been building our P indices fairly rapidly.

And there you have it, the perfect storm; an ecologically sensitive river, leaky soils and an intensively farmed catchment with a huge excess of Phosphorus.

Who the heck am I anyway? I grew up in Herefordshire, in the nutrient rich fields of my family’s dairy farm for the sake of transparency, a love for rivers sparked way back in school Geography lessons which led me to spend my working life to date trying to improve their condition. (Early retirement looking less and less likely!)

Desperate to learn about how other countries had used finances, education and regulation to address issues with soil and water I applied for a Nuffield Farming Scholarship in 2015. My studies allowed me to see regulatory approaches, funding models, voluntary and educational programmes around the world. I rapidly came to the conclusion that no single mechanism, if implemented alone, could achieve the long-term positive change we needed. There is a sweet spot somewhere in the middle and in the 7 years since my scholarship we still haven’t managed to secure it in the Wye…

What’s actually being done? With my team of advisers at The Wye & Usk Foundation, a charitable rivers trust, we provide support to about 300 farm businesses a year. This work includes the submission of more than £20m worth of Countryside Stewardship Schemes in the last 4 years to help deliver the recommendations we make. In a normal year we hold about dozen on-farm events with local partners, plus provide facilitation for three farmer groups. These enable peer to peer learning, farmers learn best from farmers, those who have changed practices are best placed to explain what motivated them, how they overcame barriers, provide insight to their methods and moral support for others following suit.

Much effort has been put in to work more collaboratively between partners operating in the same space. The Farm Herefordshire partnership brings together NGOs like ourselves and Herefordshire Meadows with local delivery staff for the AHDB, Catchment Sensitive Farming and CLA to name but a few, to share resources and deliver more effectively together.

Through our Wye Agri Food Partnership, part of the wider Courtauld Commitment instigated by WRAP, we are delivering collaborative projects with key businesses sourcing or producing food in the Wye. With the support of the Rivers Trust and WWF our work in the Wye currently involves projects with Tesco, Coop, M&S, Muller, Avara, Noble Foods, Stonegate, Kepak and most of the major soft fruit growers. We are working proactively with these businesses to reduce pollution risk at all levels of their supply chains, see our Project Case Study as an example.

Several businesses are also independently exploring new technologies to enable the export of excess P from the catchment. If these are successful they could take our P load back in to balance, and ideally in to deficit so that we can start to run down the P backlog…

To do that we need a funding framework that facilitates farming within the limits of our environment. I hoped DEFRA would agree with this ambition and submitted an application to Landscape Recovery Scheme but it was unsuccessful. We now need to find alternative routes to deliver solutions.

Along with a significant number of like minded farmers, my vision is to develop long term funding streams that would support us in delivering two key actions: 1. Running down existing high P levels by farming at low or no P input on soils at high risk of losses, and 2. Construction of wetlands downstream of high P fields to buffer the nutrient losses in the meantime.

What’s missing? One of the essential ingredients from my Nuffield learnings that is still lacking is regulation. Our Governments have little appetite to deliver on their promises and therefore their agencies have no capacity to do so either. Our Ministers and their teams in DEFRA are delusional to think that generic nationwide legislation like Farming Rules for Water could secure the necessary improvements for specific issues like those faced in the River Wye, especially when they instruct their agencies not to enforce and allow farming unions to lobby the life out of them. As a result, we are left with yet more ineffective legislation and the need for more and more layers to be added on top of all those that have gone before in the hope that one may finally do what should have been achieved long ago.

Any conclusions? The river is in a poor state. Portions of blame can be placed far and wide; water company, local authorities, farmers, processors, retailers, all of us living in or eating food produced from the catchment. But the greatest share of blame falls squarely at our Governments door. There is much good will amongst farmers, retailers and processors to deliver the necessary change and if improvements are secured it will likely be despite our Governments not because of them. In the meantime we continue to persevere, idealistic or not I believe a balance is achievable where food can be produced within the limits and to the betterment of the local environment.

Kate Speke-Adams, Head of Land Use, Wye & Usk Foundation. @HfdshireKate