By Laura Nolan and Cliona Howie, Foundation Earth

With sustainability being placed higher and higher on consumers’ agendas, people are turning to high-emitting industries to ask how they are playing their part in reducing environmental impacts on the planet. The food industry alone accounts for one third of emissions globally – and with population rising, the challenge of feeding the planet while lowering our footprint is becoming more real than ever.

Fact box

Agriculture alone accounts for 70% of global freshwater consumption (Source: FAO).

Food systems are responsible for one third of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions (Source: Nature Food).

Our global food system is the primary driver of biodiversity loss, with agriculture alone threatening 86% of the species at risk of extinction (Source: Chatham House).

Agricultural expansion drives almost 90% of global deforestation (Source: FAO).

On top of this, feeding an estimated world population of 9.1 billion people in 2050 would require raising overall food production by 70% (Source: FAO).

An increasing number of brands are making efforts to green their products, be more sustainable and communicate that to their buyers in a credible way. Many green claims are being made left, right and centre – but how do you back up and qualify a food product’s eco-friendliness in an accurate, transparent way? What is being measured exactly, and what information and data can we access to verify such claims? How can we move towards a food system that doesn’t just reward client-facing brands, but also farmers and producers who contribute to making value chains more sustainable?

The role of ecolabels

One example is the use of ecolabels placed on products, that show consumers just how much that item costs the environment in an easy, accessible way (you’ve most likely seen those traffic light systems on your home appliances!). This trend isn’t new: 84% of consumers believe it’s important for each person to contribute to sustainability (Source: Kerry Group, “Sustainability in Motion”), and many companies are starting to respond to the demand for corporate transparency – from fashion, to beauty, electronics and of course, food.

But what do ecolabels show exactly? Well, there are over 500 environmental labels out there: a lot of them focus on carbon footprint (CO2 emissions), some will tell you if a product is organic or not, and others try to look at a broader range of measures like water use, water pollution and biodiversity. Some even include other ethical indicators such as working conditions or animal welfare. The scopes are large and diverse, there is no “one size fits all”, and there isn’t a consistent, harmonised approach.

Regulation is underway – the European Union has worked towards the development of a unified method to communicate environmental information of products across the European Union – the Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) Method – since 2013. PEF, for example, measures 16 different environmental impact categories. The French government has also been building a national environmental scoring system for food products, and similar initiatives are underway in The Netherlands and Denmark.

We need better data!

And yet, current approaches to assess the environmental impacts of individual food products remain limited. Often, proxy data is used to generate an estimate of a product’s impact, and the true impact of a specific product is never known. That means that if an actor in the value chain (for example a farmer) is making active efforts to green its processes, that most likely won’t show up in the final score due to the use of averages.

Impact scores based on secondary data are easier, quicker and cheaper to obtain, but without accurate information on a product-by-product basis, environmental impacts cannot be meaningfully managed and the climate crisis will intensify. And without an accurate per-product understanding of where the highest environmental impacts are in a supply chain, food producers are not incentivised to grow, manufacture, transport or sell their products more sustainably.

Here’s the thing: ecolabels don’t only help consumers choose a product – when the assessments are done accurately and in-depth, using methods such as Life Cycle Assessments (LCA) for example, they can also help food producers reduce the environmental impacts of their production and produce in a better way. They act as key source of intelligence to help industry players pinpoint where their highest impacts are, and what can be done to improve them. That’s when ecolabels also become a powerful data-driven tool to build more sustainable food systems.

At Foundation Earth, we are working to develop a method that scores food products in the most accurate way possible, based on LCAs using the highest quality data available. We map the supply chain, assess the impacts throughout and tell brands where they might be going wrong. At the same time we are comparing different existing methods to pull out the best of them all and create a single method that will allow brands to have a comprehensive view of their supply chain and know where improvements can be made.

Recognising actors across the supply chain

So, brands are starting to place more and more emphasis on their sustainability efforts – but what does this mean for the other actors along the supply chain? The nice shiny label is sitting on the product pack, but how does that help all food players, from farmers to marketers, to demonstrate their sustainability efforts?

For now, it doesn’t really. Everyone in the chain has contributed to that final score (either negatively or positively!), so why do they miss out on the acknowledgement? At Foundation Earth we believe there is a real gap here, because to transform entire food systems we need to recognise the do-gooders and incentivise others to join in these efforts. If a farmer is doing their best to place sustainability at the heart of their business model, and probably even seeing the direct benefits of their actions on biodiversity around them – for example – this should be celebrated. Because every effort counts.

That’s why we are launching new pilots calling all pioneers to be part of Foundation Earth’s trials and pave the way for food system transformation. We are aiming to deliver a standard, scalable product footprinting system not only for brand owners but also producers and retailers, that will connect entire value chains and give recognition where it is due by delivering our label across the chain. This will in turn unlock commercial value for businesses and support all actors in achieving their net-zero goals.

A food ecolabel for all

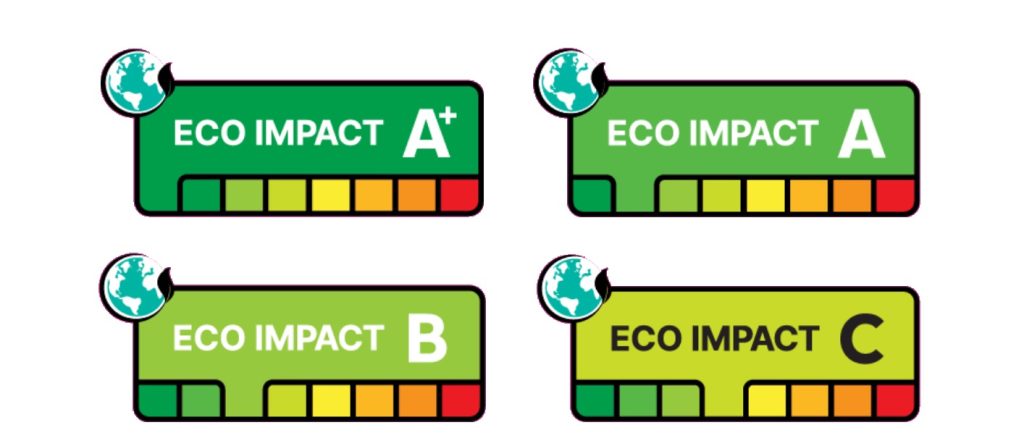

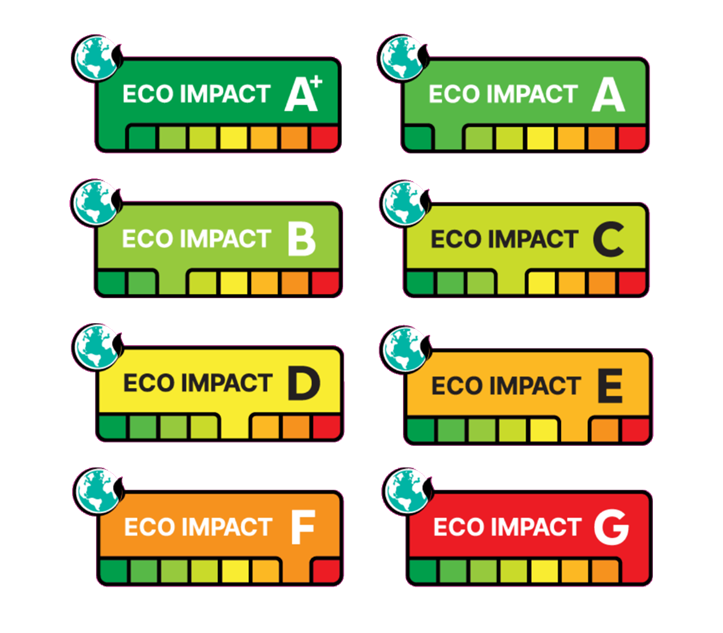

What will this look like concretely? We already have our scoring system for final products – remember that traffic light system mentioned on your home appliances? Our Foundation Earth Eco Impact labels apply a similar system: our scores range from A+ to G (A+ being green and representing the lowest environmental impact, G being red and representing the highest) and are re-certified yearly, making it possible for products to improve their grade. But instead of labels just being on final, packaged products, ingredients and processes could be certified at each step of the value chain as well, bringing recognition to all those businesses applying sustainability principles and helping business-to-business (B2B) buyers find alternative, sustainable options.

Transforming food systems for the better will take active participation from us all. And it’s only by recognising and celebrating efforts that we will build a movement big enough to create actual change and leave way for food systems that won’t harm the planet.

Highlights

Sustainability is being placed high on consumers’ agendas, and as a result being reflected more and more in brand’s business models.

Ecolabels are a powerful tool to give consumers the confidence to choose more sustainable products.

There are many existing ecolabelling schemes and methods, that look at various indicators. The European Union has worked towards a unified method, the Product Environmental Footprint (PEF).

Currently a lot of methods use proxy data – industry averages – which don’t reflect the true impact of an individual product.

Undertaking Life Cycle Assessments (LCA) on individual products enables accuracy and generates intelligence to help businesses produce in a better way.

We need to not only recognise the brands, but all producers from farm to retail. A certification scheme across the value chain could reward those sustainability efforts and incentivise others.